Resolving Europe’s NPL burden: challenges and benefits

Keynote speech by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at an event entitled "Tackling Europe's non-performing loans crisis: restructuring debt, reviving growth" organised by Bruegel, Brussels, 3 February 2017

I am grateful for this opportunity to speak on the important issue of NPLs in European banks at the invitation of Bruegel, a think-tank doing such significant work in shaping economic thinking in Europe. My remarks today will be on the euro area non-performing loan (NPL) problem and on the policy response that would be needed from a macroprudential perspective. I will first outline the size and scope of the NPL problem. I will then put the NPL problem into a microeconomic and structural context, focusing on the reasons why it has developed this way and what the impediments are to an exclusively market-based solution to the problem. With this in mind, I will move on to the range of necessary and feasible solutions, underlying in particular the role of securitization schemes and the creation of Asset Management Companies (AMC) to achieve an orderly and fast resolution of NPLs.

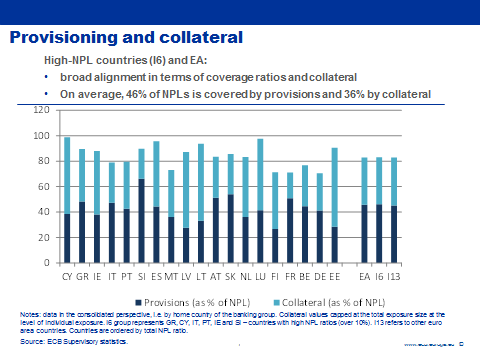

The NPL problem is one of the main reasons behind the low aggregate profitability of European banks. Let me recall here that the return on equity of euro area banks has hovered around 5%, which does not cover the estimated cost of equity. It is important to keep in mind that the issue is not about the robustness of balance sheets as capital and provisions have significantly increased since 2012. Indeed, whereas CET1 ratio was 7% in 2007, it reached 9% in 2012 and is now 14%. Including provisions and collateral, the NPL coverage ratio stands at 82% on average, both for the group of six countries with higher NPLs and for the euro area as a whole.

Asset quality issues have been brought to the fore by the global financial crisis. In the euro area, NPL ratios stood at low or manageable levels prior to the crisis. At the same time, the NPL problem has deep structural reasons that were further amplified with the start of the financial and economic crisis. In fact, the surge in NPLs further revealed the limited ability of large parts of the euro area banking system to deal with distressed debt.

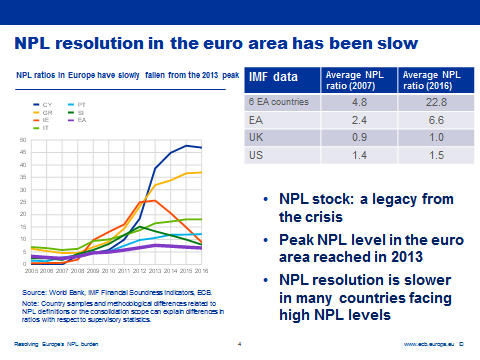

Chart 1

In the euro area, the average NPL ratio peaked at 8% in 2013 (see Chart 1).[1] As the economic recovery took hold, GDP growth resumed and unemployment started to decline, this ratio started to fall. The reduction in NPLs has, however, been slow and heterogeneous. The ratio of NPLs is still at two digit level in six i euro area countries: Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Slovenia. Banks directly supervised by the ECB, still held €921 billion of such troubled loans at the end of September 2016, representing 6.4% of total loans and equivalent to nearly 9% of the euro area GDP.[2]

The NPL outlook is also very diverse across the euro area. In two countries, Cyprus and Greece, about one-half of total loans are not performing, accounting for about one-third of total bank assets. Four countries report NPL ratios of close to 20%. On the other end of the spectrum, many countries maintain NPL ratios of less than 3%. Despite this heterogeneity, NPLs are a problem with a clear European dimension, as even those countries where banks do not struggle with asset quality, are likely to be affected by spillovers, both financial and real.

The NPL problem has no comparable dimension in the U.S. for a number of reasons ranging from structural, to regulatory- and tax-related motives. In the U.S., Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs), and not the banks, account for the majority of mortgages in their balance sheets. Differently to Europe, regulatory requirements overlay accounting standards imposing the write-down of loans to their recoverable collateral value already after six months past-due, for example. The IAS 39 accounting standard (under the incurred loss approach) and the absence of guidance on write-off requirements tend to lengthen NPL write-offs in Europe.

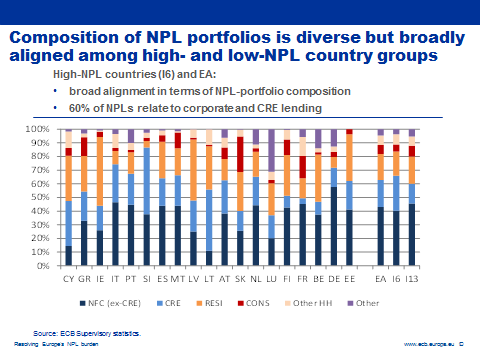

The distribution of non-performing exposures by sectors is also quite mixed across countries. Taken together, about 60% of currently distressed loans were extended to non-financial companies, of which about a third is related to lending backed by commercial property. But lending to households also constitutes a significant part of troubled debt exposures, accounting for more than a half of the NPLs in some countries. The distribution of non-performing exposures of high-NPL countries (with NPL ratios in excess of 10%) broadly follows this pattern (see Chart 2).

Chart 2

Clearly, a sizeable part of the NPL stock is no longer a risk to bank balance sheets. Provisions, made under applicable accounting standards, amount to about 46% of the stock of NPLs. The remaining value of NPLs is supported by expected future recoveries. Collateral may be a major source of value in NPLs, covering a further 36% of the total exposure, bringing total coverage to 82% on average, for the euro area, broadly in line with the figures for the high-NPL countries (see Chart 3). However, it is very important to bear in mind that access to that collateral is often lengthy and costly, eroding its net present value.[3]

Chart 3

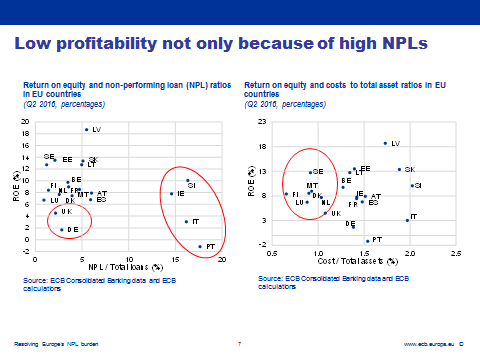

As I said earlier, one of the main reasons we are concerned about high NPLs, from a macroprudential perspective, is that they weigh on bank profitability. However, the resolution of NPLs should not be seen as the only challenge on the way towards restoring sustainable bank profitability and the banking sectors’ ability to lend to the real economy. Low returns on equity in the euro area are also the result of high costs or overbanking. Only a few EU countries have successfully managed these challenges. Sweden and other Scandinavian countries are a notable example of a banking sector that achieves high profitability while not being burdened with legacy credit quality issues or excessive cost inefficiency. Digitalisation, optimisation of human resources and branch networks, as well as reduction of overbanking also need to be addressed, drawing lessons from the Swedish and other case studies (see Chart 4).

Chart 4

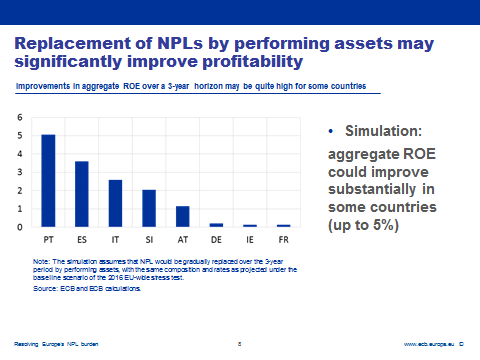

That being noted, the resolution of NPLs alone could lift up the return on equity in several European countries significantly. ECB staff carried out some simulations to demonstrate the potential for increases in bank profitability. In these simple and stylised settings, the assumption was made that non-performing loans would be replaced by new, sound exposures. Interest income would be boosted as a result, as rates charged on new business would substitute for the lower earnings from non-performing loans. Our simulations suggest that a resolution of NPLs could improve the aggregate return on equity of euro area banks by at least 1 percentage point, with some sectors gaining 3 or 5 percentage points. These estimates do not account for the benefits of lower funding cost or lower capital requirements that would be forthcoming from a reduction of NPLs. And, this would provide even further upside to bank profitability. (See Chart 5)

Chart 5

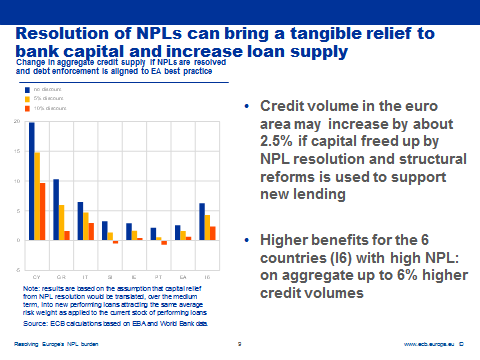

The capital relief from the resolution of NPLs may further spur loan supply (see Chart 6). In the medium term, if the entire amount of capital currently tied up by NPLs is used to support new lending, total credit volume in the euro area may increase, in the most optimistic variant, by about 2.5% and up to 6% in the group of 6 countries with higher NPLs. These numbers would likely be higher if dynamic and confidence effects, that are not possible to account for, would be added. Clearly, countries with the highest NPL ratios and the least efficient debt enforcement frameworks would benefit the most.

Chart 6

Let me now look more closely at some of the reasons for the slow resolution of NPLs.

If financial markets were fully efficient, one would assume that NPLs would be priced in a way that would result in fast market clearance and their removal from banks’ books. Market transactions of loans are, however still insufficient, having attained nevertheless, about €200 billion of loan portfolio sales in the last three years – an amount that does not include necessarily only NPLs.[4]

The standard microeconomic concept of a market with asymmetric information (the problem of “lemons” or bad cars in the U.S.)[5] is helpful in explaining the lack of current activity in NPL markets. Consider that NPLs may come with a quality level that is unknown to the buyer, but can be discerned by the seller who originated and managed the loan. Asymmetry of information available to the seller and the buyer may then lead to an outcome where only low-quality assets, (“lemons”) are actively traded. The uninformed buyer would not be prepared to pay a higher price for higher-quality assets, given that they are not recognised as such. As a result they would be retained on the books of the seller.

There are many sources of asymmetric information in the NPL context. First, while even the banks do not know everything about their assets, they certainly have an advantage over the investors, coming from the previous relationship with the borrower. Presence of collateral further increases the asymmetry and the cost of investor due diligence. Furthermore, investors may fear that banks cherry-pick the best assets for themselves, thus reducing the quality of portfolios offered on sale.

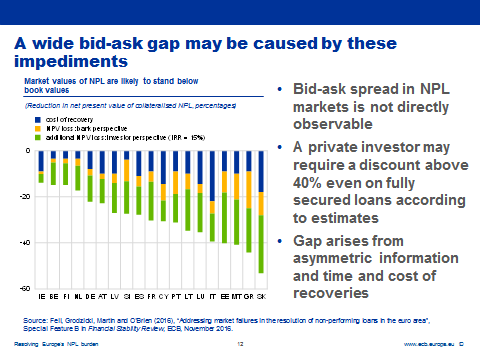

Beyond market failures, regulatory and features of the judicial system, such as structural inefficiencies in debt and collateral enforcement, also contribute to the lack of market turnover. Legal procedures needed to collect a simple claim take too long and cost too much in many euro area countries. Some of these costs cannot be recognised in the values of NPL, but rather, according to accounting rules, are charged to the general expenses. This discrepancy between economic and book value of NPLs is yet another disincentive to increase supply, especially for those banks that are not sufficiently profitable or that have thin capital cushions (see Chart 7).

Chart 7

On the demand side, investors are also deterred by high uncertainty around recoveries and their timing. Moreover, barriers to entry such as licensing requirements further inhibit demand in some euro area countries.

The direct consequence of the conditions, under which the NPL market operates, is a wide gap between bid and ask prices. The data on the size of that gap is scant but it is thought to be very large. For instance, estimates suggest that, for a fully collateralised non-performing loan, the discount required by a private investor may exceed 40% solely due to the cost, time and uncertainty of the recoveries (see Chart 8).[6]

Chart 8

Most of the factors contributing to the discount would not be recognised in banks’ provisioning. Under IAS 39, the current accounting standard which is to be replaced by IFRS 9, provisions are made under the incurred loss approach.

Investors who have limited information would use a much higher discount rate (corresponding to the green bars in Chart 7) to reflect their uncertainty about the quality and thus the value of the loan. They would additionally account for the full expected cost of working out the loan (blue bars). This calculation produces a wide bid ask gap.

Structural reforms that would reduce all the impediments mentioned, would raise the net present value of the non-performing loans on bank balance sheets, thereby providing an important and welcome buffer to absorb further losses and increase the range of options available to resolve NPLs (see Chart 9).

Chart 9

It would not suffice, however, to develop and stimulate market-based solutions for the high stock of NPLs. Some assets may still not attract investor demand due to their intrinsic features and, in the case of some assets, banks may have an advantage over investors, making in-house work-out of NPL the preferred option, which in turn requires that they have sufficient capacity to restructure and cure troubled loans.

Comprehensive strategies are therefore needed to address the NPL problem. These strategies should include common elements. For these elements a harmonised approach at the European level is of utmost importance, complemented with country-specific elements in each high-NPL constituency in the euro area.

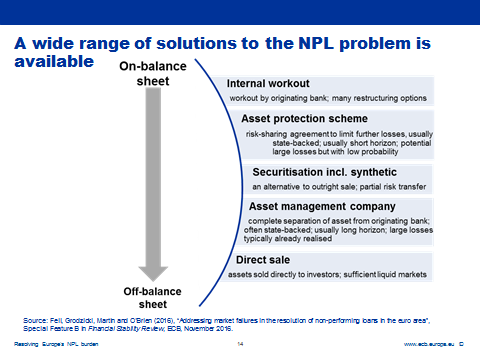

Generally speaking, NPL resolution strategies can deploy a broad range of options available to banks and policymakers. These options are usually complementary. Internal workout by the bank originally holding the impaired asset marks one end of the spectrum of options and should always feature highly in any broader resolution scheme. On the opposite end, direct sales to investors offer an opportunity to dispose of NPLs quickly. In between, there is a range of options such as asset protection schemes (APSs), securitisation and synthetic securitisation and the creation of asset management companies (AMCs), which in the past often involved state intervention (see Chart 10)

Chart 10

All of these options require a considerable push for structural reforms. To illustrate this point, let us consider an AMC which is not accompanied by improvements to the debt enforcement framework. As the AMC would be in an equally difficult legal position as the originating banks, the synergies it could reap would be very moderate. In turn, either the upfront impact of the AMC transfers on the solvency of the banks, or the likelihood of the AMC having to shoulder the losses would be unacceptably high.

It is therefore essential that, as part of the comprehensive strategy, governments take a range of actions related to debt enforcement and reduction of information asymmetries. In many countries, the menu of options available to creditors in insolvency should be expanded, with an objective of promoting early restructuring and survival of viable companies. At the same time, the liquidation of non-viable companies and access to collateral should be facilitated. Strong implementation of the necessary legal reforms is also crucial. This involves e.g. the provision of adequate capacity of the court system and well-functioning of out-of-court workout schemes.

Moving to information asymmetries, the quality, scope and accessibility of financial information should be improved, in particular with respect to corporate financial data and information on assets of distressed debtors. Finally, remaining obstacles to third-party investment in distressed loans should be reviewed and where possible removed.

On the supervisory side, NPL resolution has been designated as one of the top priorities of the Single Supervisory Mechanism. ECB Banking Supervision has prepared an extensive draft guidance document on NPL, expressing supervisory expectations with regard to governance, management, recognition and valuation of NPLs, which was discussed at length earlier today.

The powers of the banking supervisors in the EU are, however, legally limited. For instance, Accounting Standards, including on the imposition of provisions for non-performing assets, are not set by supervisors.[7]

Other elements are likely to be needed for a comprehensive solution. History has proven that asset management companies can swiftly clean up NPLs from bank balance sheets, and resolve them over a longer period of time. Acquisition of assets at their long-term economic value, instead of market value which is depressed by low liquidity and high uncertainty, minimises fire sale losses. For example Sweden, Korea, Germany, Ireland, Spain and Slovenia used these tools to manage banking crises, often with a focus on loans backed by real estate. While overall successful, the degree of success of such entities tends to be linked to strong governance. There is one common feature of this type of AMC: state support. Until now AMCs have rarely been established on a purely commercial basis. Governments had to step in to provide capital to banks weakened by the recognition of losses on NPLs transferred to the AMC, and to guarantee the funding of the AMC. Privately-led solutions would be clearly preferable but have thus far been hardly feasible.

Is there then a place for such AMCs under the current European regulatory framework which puts the burden of managing financial crises on private creditors and investors? There is scope for public sector involvement. It is possible to use government guarantees for funding purposes, as done recently in Italy in the context of bank funding and securitisations of NPLs, in full compliance with the rules and at a market-consistent price. The rules also allow for precautionary recapitalisation of banks by the public sector in cases of significant financial stability concerns, subject to strict conditions laid down in the BRRD (Art. 32, 4), covering hypothetical losses estimated under an adverse scenario of a stress test. Precautionary recapitalisations also have to respect State Aid rules that generally require bail-in of subordinated debt as stated in the European Commission’s communication of July 2013, where possible exemptions are nevertheless foreseen (paragraph 45). [8]

The toolkit would be rounded off by two more instruments which facilitate sales of NPLs.

Clearinghouses can be established to reduce the information asymmetry. Standardised data on individual assets could be stored on a centralised platform at European level, which would combine exposures from multiple banks and vouch for quality of the data. This would allow investors to carry out a due diligence at low cost. Bespoke portfolios could be constructed in line with the mandates and objectives of individual investors.

Securitisation could complement outright NPL sales. One of its advantages is that the universe of distressed debt investors can be expanded. Thanks to the ratings given to senior tranches, a broader group of investors could acquire NPLs. Additionally, securitisation offers another way through which governments may jump-start the NPL market, for example by co-investing, together with private investors, in junior or mezzanine tranches. As with AMCs, of course, such investment would need to be compliant with state aid requirements.

Many of these measures should not be expected to yield fruit immediately. Only AMCs, to the extent that they are in compliance with the current rules and securitisation can offer a quick clean-up of bank balance sheets.

An AMC at European level would be a welcomed initiative, particularly because it would facilitate raising private funding in the market. A true European AMC faces however difficulties in the present environment. In more immediate terms, a way forward could be the creation of a European blueprint for AMCs to be used at national level. This European blueprint should clarify what is possible within a flexible approach to the existent regulation and encourage countries to adopt all necessary measures in a well-defined time frame.

At the same time, a European NPL-information platform should be implemented to enhance transparency and facilitate transactions.

In the medium term, the introduction of IFRS 9 and more forward-looking provisioning rules could be conducive to faster recognition of losses. Improvements to bank practices and to data quality and availability are also going to take time before progress becomes tangible.

Finally, insolvency law reforms tend to take a number of years, including the time needed to build capacity, develop practices and test the rules in courts.

The long horizon of many measures should not reduce the sense of urgency and necessity. All of these reforms are essential not only for the resolution of Europe’s NPL burden, and also as prevention of the renewed build-up of NPL in future cyclical downturns. Financial benefits of speedy action may surface more quickly too. If these measures become credible, investors will recognise the shift in policy and should price higher expected future returns into loan valuations.

Let me conclude. While NPLs are rightly seen as a problem, their resolution could unlock significant benefits to the European banking system and the European economy.

The benefits from resolving the NPL problem are unquestionable, but a great deal of hard work is clearly needed, on many fronts, to deliver them. Neither a partial solution, nor further waiting is an option. Acting only on the supply side of the NPL markets and forcing banks to sell may have serious financial stability consequences. The resulting transfer of value from banks to the investor community would put further pressure on bank profitability, instead of relieving it. For this reason, a comprehensive, co-ordinated effort on the part of several European and national authorities is now crucial.

[1]Based on the IMF Financial Soundness Indicator database.

[2]According to the ECB Supervisory Banking Statistics.

[3]The value of collateral reported in supervisory statistics is capped at the value of the exposure, therefore the actual collateral pledged against NPLs is likely to be significantly higher.

[4]See Deloitte (2016), “Deleveraging Europe 2016. H1 Market Update”.

[5]See G. Akerlof (1970) “The market for “lemons”: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism” in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol 84, No. 3, pp 488-500.

[6]See Fell, J., M. Grodzicki , R. Martin and E. O’Brien (2016), “Addressing market failures in the resolution of non-performing loans in the euro area”, Special Feature B in Financial Stability Review, ECB, November 2016.

[7]See ECB (2016), “Stocktake of national supervisory practices and legal frameworks related to NPLs”, September 2016.

[8]On the possibilities of interpreting the relevant European legislation see the recent CEPS Special Report by Bruzzone, Cassela and Micossi (2016) “Fine-tuning the use of bail-in to promote a stronger EU financial system”, CEPS Special Report No 136, April 2016.

Европейска централна банка

Генерална дирекция „Комуникации“

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Възпроизвеждането се разрешава с позоваване на източника.

Данни за контакт за медиите