Business models in banking: Is there a best practice?

Speech by Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBCAREFIN Conference on “Business Models in Banking: Is There a Best Practice” at Bocconi UniversityMilan, 21 September 2009

Ladies and Gentlemen, [1]

It is a real pleasure for me to speak today at Bocconi University. Founded in 1902, Bocconi was the first Italian university to offer degrees in economics. As one of the oldest economics departments in Europe, Bocconi leads the way in intellectual thinking on economic progress and innovation. It therefore seems the perfect place to host today’s conference on banking business models and to discuss their future.

Given that the worst financial storm since the 1930s is only gradually calming down, the topic chosen for this conference is very apt. Banks have taken centre stage in the ongoing financial and economic crisis, and any definitive resolution to the crisis essentially hinges on banks regaining financial health and public confidence on the basis of sustainable and welfare-enhancing business models.

However, not all banks have been equally affected by the crisis, nor have they been equally responsible for it. The main players have mostly been large international investment banks or banks that had moved away from traditional retail banking activities. This movement towards a presumably more “modern” business model relied principally on the origination, distribution and trading of often complex securities, on other fee-income generating activities, as well as on a funding structure more dependent on wholesale markets.

Many factors have contributed to the current financial crisis, namely excessive risk-taking, the emergence of a shadow banking system, the exponential growth of innovative financial products, inadequate corporate governance incentive structures at banks, the lack of proper regulation and an environment of abundant liquidity at low interest rates. But my speech today is going to focus on excessive risk-taking and banks’ creation of innovative financial products, which has led to the transformation of their business models.

To a large extent, this shift towards a new business model was based on innovation in the structured credit market, particularly in respect of securitisation instruments, such as credit default swaps, asset-backed securities and collateral debt obligations. A common feature of all these financial innovations is that they transform, transfer and trade credit risk. One of the main consequences of the use of such instruments is that large amounts of credit that were previously predominantly illiquid (such as bank loans) then became liquid and could potentially be traded in financial markets.

However, we must not blame such credit risk transfer instruments and vehicles per se I am confident that those instruments generating real economic value will survive the crisis, albeit probably at much reduced volumes, in less complex structures, with improved transparency, and subject to financial regulation and supervisory structures. They will survive because, when prudently applied and sufficiently monitored in terms of their impact on financial stability, financial innovations generally tend to make a financial system more efficient without necessarily increasing its fragility.

At this point, it is worth asking what the main banking business models could or should look like from a policy-maker’s perspective, which takes into account implications for both financial efficiency and stability. I will limit the remainder of my speech to a few of the main points of the argument and will also point out some early lessons to be learnt from the crisis.

What is so special about the business of banking?

I will start with a standard definition of a “bank”, recalling the main functions that banks are supposed to perform and explaining why these functions are so important and special that they warrant relatively close public intervention and oversight.

A bank is “an institution whose current operations consist in granting loans and receiving deposits from the public”. [2] This definition refers to the core activity of commercial banks, namely the simultaneous acceptance of deposits and offering of loans, which distinguishes them from other financial intermediaries. However, banks typically conduct a broader range of activities, which can be subsumed under the following three functions: [3]

First, banks provide the public with liquidity (money) and payment services through their deposit-taking business.

Second, banks transform assets in terms of denomination, quality and maturity, as well as manage the associated risks.

Third, banks process information and monitor borrowers using specialised technologies. In so doing, they often establish long-term relationships with their clients, which may further mitigate the negative impacts of adverse selection and moral hazard on the resource allocation process.

Changes in banking business models

Before I turn to the question of how this traditional banking model has changed over the past few years, I am going to take a brief look at financial market history.

Glass-Steagall: investment banks versus commercial banks

Looking specifically at the history of the financial markets in the United States, it was bad banking practices and the public outcry after the stock market crash of 1929 that brought about the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Interestingly, the Act followed an enquiry into whether commercial banks had sold unsound securities to their customers, thus converting potential bad loans into securities issues. The Act therefore prohibited commercial banks from underwriting, holding or dealing in corporate securities, either directly or through securities affiliates. [4] In my view, the concerns that prompted the Act were very similar to those currently being voiced – particularly in relation to concerns about banks’ business models and the sale of unsound securities to unsuspecting investors.

The Act had a global impact on competitive conditions. For instance, the large presence of major US investment banks in Europe can be traced back to the implementation of this Act, which separated investment banks from commercial banks. The Act also had an impact on the supervision of banks, mostly in the United States, but also in other regions in the world, including Europe. Owing to the funding structure of commercial banks and the stronger links between them – and hence their importance for financial stability – commercial banks were regulated accordingly. In contrast, investment banks were expected to be in less need of close monitoring and regulation, as they were seen to be less important from a financial stability perspective. The current crisis has vividly illustrated how the actions of not only commercial banks and investment banks, but also other financial players, can have a major impact on all parts of the financial system and the economy at large.

I should now like to focus on two major factors that have changed the way banks do business. First, I will discuss the changes in banks’ business models that relate to the sources of their revenue. And, second, I will focus on the changes in the funding of banks and talk about the unintended consequences of the expansion of their securitisation activities.

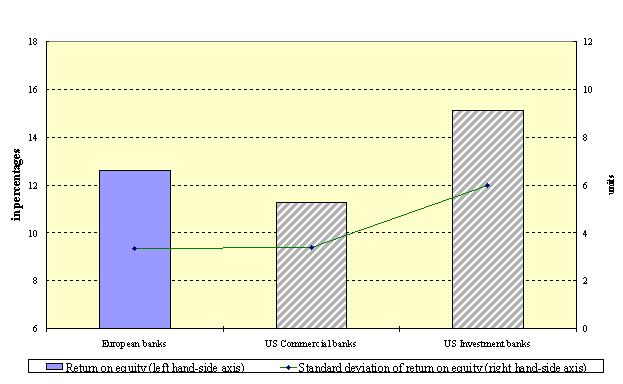

Diversification in the sources of revenue

With regard to the change in the sources of banks’ revenue, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 is a prime example of deregulation in relation to banks’ business models. If we compare the regulations in place today with those of 20 years ago, we see an unprecedented process of deregulation across regions and financial sectors. One consequence of this deregulation has been a global trend towards more diversification in banks’ income sources, i.e. towards higher brokerage fees and commission – more generally called “non-interest income”. The increase in non-interest income provides banks with additional sources of revenue and can therefore provide a diversification in their overall income. At the same time, non-interest income has usually been a much more volatile source of revenue than interest rate income. Investment banks, for example, have a high dependence on non-interest income. Typically, they are more profitable than traditional commercial banks, but they are also much more leveraged and their earnings are more volatile (see Chart 1). The volatility of earnings, combined with the close ties of investment banks to other financial players, calls for a higher level of monitoring for these systemically important players. [5]

Chart 1: Bank profits and volatility of earnings

(median values of return on equity and standard deviation from 2000 to 2007)

Source: Bankscope.

In addition, there is one problem relating to the banks’ risk management that applies mostly to investment banks, but also to other large financial institutions: most risk management techniques neglected the correlations of risks across securities, as not just banks, but also rating agencies, did not sufficiently internalise the growing systemic, market and liquidity risks. Moreover, banks underestimated tail risk. The existing risk-management techniques worked well at predicting small day-to-day losses in the middle of the distribution but failed to anticipate severe losses that are much rarer. But clearly, it is exactly those severe losses that matter most. This mispricing of risk relates to deficiencies in risk management techniques, but also, and perhaps more importantly, to existing incentives in the banking system oriented towards the short term profitability of banks.

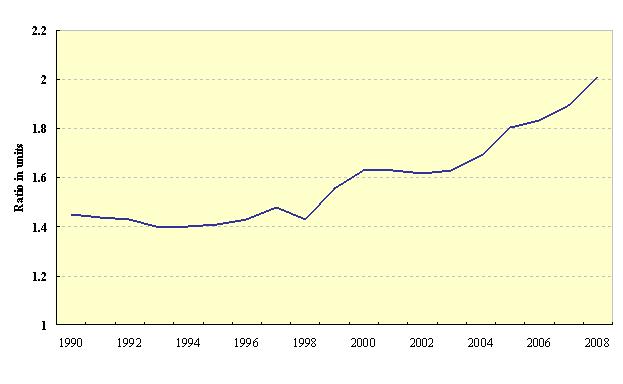

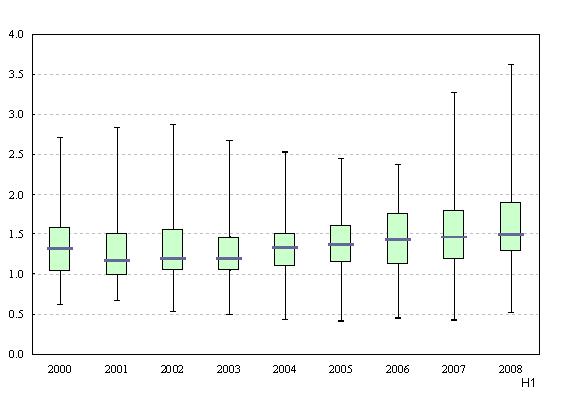

Diversification in the sources of funding

Turning now to the second factor, the change in banks’ funding sources: at the same time as the change in the sources of banks’ revenue, there has been a wider change relating to banks’ liability side of the balance sheet. [6] In particular, this refers to the shift in banks’ business models away from the traditional model of financing. In the traditional model, there was a heavy reliance on retail deposits, but this has been replaced by an increasing reliance on market-based sources of funding. The significant recourse to specific funding instruments, such as mortgage bonds and securitisation, has made banks increasingly dependent on capital markets, but at the same time, of course, less dependent on deposits, to expand their loan base. This is evident from both an upward trending total assets to deposits ratio of the largest euro area banks (see Chart 2.a) and an increase in the loans to deposit ratio of large EU banks (see Chart 2.b). To the extent that more stable retail deposit financing has been replaced by wholesale funding, banks may have become more exposed to market dynamics and perceptions, constituting a potential source of instability in the banking sector. [7]

Chart 2.a: Total assets to total deposits of the largest euro area bank

(outstanding amounts, eonia banks)

Source: Bankscope.

Chart 2.b:Loans to deposit ratio of large EU banks

(corrected for extreme outliers)

Source: Bankscope.

Securitisation markets and the current crisis

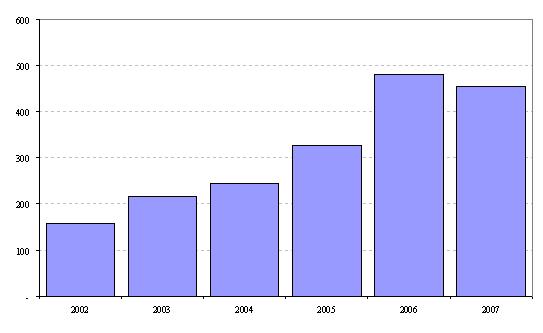

The element of this change in banks’ sources of funding that I would like to focus on in particular is securitisation. Securitisation activity did indeed increase substantially in the years prior to the financial crisis (see Chart 3). As you know, securitisation and financial innovation in credit markets have generated significant changes, particularly in the financial structure of banks, and, more generally, in financial market activity in the euro area. It has become clear that the change in banks’ business models from “originate and hold” to “originate, repackage and sell” also had significant implications for financial stability. Securitisation was meant to disperse credit risk to those who are better able and more willing to bear it. But, as the current crisis has shown, this did not work out as envisaged. This stems from the fact that the same instruments that are used to hedge risks also have the potential to undermine financial stability – by facilitating the leveraging of risk, for example. Moreover, there were major flaws in the actual interaction among the different players involved in the securitisation process. These included misaligned incentives along the securitisation chain, a lack of transparency with regard to the underlying risks of the securitisation business, and the poor management of those risks. There was a dramatic increase in the complexity of securitised products prior to the crisis, owing largely to misaligned incentives and investors’ search for yield, which, in particular, made the valuation and risk assessment of these products extremely complex and difficult.

Chart 3: Securitisation issuance in Europe

(in EUR billions)

Source: European Securitisation Forum.

In contrast, the covered bond market has been more sheltered from these incentive problems than securitisation markets, partly because traditional covered bonds have a simpler structure. This makes the overall market more transparent, and the valuation and risk assessment easier. Covered bonds also have a much stricter regulatory framework.

Overall, there have been problems in the securitisation market that relate to opacity and misaligned incentives, which – looking ahead – need to be addressed by market participants and regulators in order to restore the securitisation market to health.

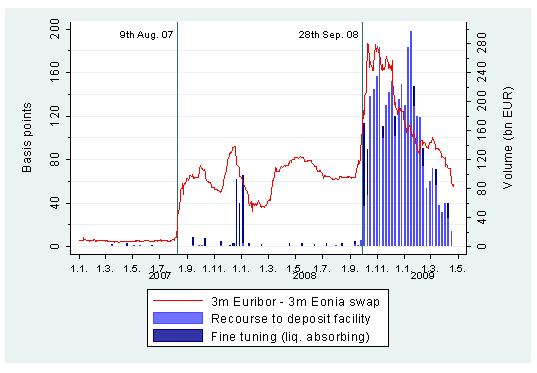

Money market problems as a symptom

Having gone through some of the major factors that have affected the condition of banks during the current crisis, I will conclude by recalling not only the exceptional speed with which the crisis hit the financial sector, but also the unprecedented size of its impact. Consider, for example, interbank markets. In normal times, interbank markets are among the most liquid in the financial sector. In 2006 the daily turnover in euro area money markets was €140 billion. [8] The sudden seizing up of interbank markets and subsequent failure to redistribute liquidity has become very much a key feature of the financial crisis. [9] Chart 4 shows the spread between the three-month unsecured rate and the three-month overnight index swap rate, which is a standard measure of interbank market tension. Until 9 August 2007, which is often said to mark the start of the financial crisis, the unsecured euro interbank market was characterised by a very low spread of around five basis points. After the announcement by BNP Paribas that it would freeze some funds, the spread increased by a factor of 12 to around 60 basis points. After the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the events surrounding the last weekend of September 2008, [10] the rates shot up further, eventually reaching a maximum of 186 basis points. The increase of rates in September 2008 is mirrored by the amount of funds deposited with the ECB at that time.

Chart 4: Interbank market

Source: F. Heider, M. Hoerova and C. Holthausen (2009), op.cit.

The events of the last two years have not only shown that even the most liquid funding markets for banks can seize up within days, but also proved that long-standing economic relationships across different market segments can suddenly break down precisely as a result of the links between banks. Future regulation will take into account liquidity risk and prescribe sound liquidity policies.

How banks have fared during the recent financial crisis

The recent financial crisis has illustrated how banks’ own business models and incentives can have a major impact on financial stability. In this regard, recent international evidence suggests that banking strategies that rely primarily on generating non-interest income or attracting non-deposit funding are very risky. [11] There is also evidence, for example by Andrea Beltratti, from Bocconi University, and co-authors, suggesting that those banks that performed better prior to the crisis have also fared worst during the crisis. This seems to suggest that the more profitable strategy prior to the crisis, has also been the more riskier strategy. Their research findings also suggest that there may be additional policy tools that could contribute to containing future threats to financial stability. In particular, banks in countries with stricter capital requirements and more independent banking supervisors seem to have performed significantly better during the crisis. Also, banks with more Tier I capital and in countries with more restrictions on banks’ activities have also done relatively well in recent quarters. [12]

The way forward

What have we learnt about sustainable bank business models from the events of the past two years? First, it is important that the structure of banks’ liabilities is appropriate for the structure of the assets that they hold. Banks have been excessively leveraged relative to the risks they were taking.

Second, we still know too little about why different banks hold different levels of equity. [13] We do know, however, that, ultimately, equity is the only robust buffer against realising losses. Although holding equity is costly, bank capital regulation should also take into account the macroeconomic implications of bank capital requirements.

Third, banks to a large extent ignored the role of deposits as a stable source of funding. More and more assets were funded by non-deposit liabilities. Banks turned excessively to the wholesale markets in order to finance their growth. Relying on wholesale markets for funding and liquidity has proved to be exceedingly precarious.

Fourth, owing to its potential benefits, innovation in the financial sector will continue. However, a serious evaluation of the possible implications of financial innovation for financial stability is warranted. In the case of securitisation, a sharp reduction in the level of complexity and leverage of the instruments issued is expected, while a higher level of transparency and more aligned incentives are crucial for an efficient securitisation market.

Fifth, I would like to just say a few words on the macro-prudential aspects of financial stability. It is very important to develop a proper framework for the macro-prudential supervision not just of banks, but also other financial institutions, markets and instruments that can be systemic in nature, irrespective of whether they are regulated or not. For that, we need a deep understanding of the major trends in the financial sector, including new business models, and their impact on financial stability. [14]

I am pleased to note that the relevant authorities have already started to take action in response to all these lessons that have been learnt from the financial crisis. With a view to strengthening the resilience of the banking sector, the regulatory reform agenda that has been launched and agreed internationally will:

introduce a leverage ratio, as a measure to curb banks’ excessive balance sheet growth. This measure will be introduced initially as a supplement to the Basel II risk-based framework and, subject to proper calibration and review, as a minimum regulatory requirement;

raise the quality, consistency, transparency and level of capital, namely the amount of common equity and other instruments of equally high loss-absorption capacity;

introduce a framework for counter-cyclical capital buffers above the minimum capital requirement, which will be raised during economic upturns and be used in downturns, as well as promote more forward-looking provisions; and

establish a minimum global standard for funding liquidity which includes a stressed liquidity coverage ratio requirement and a longer-term structural liquidity ratio.

These measures will be introduced by the end of the year, and phased in as financial conditions improve and economic recovery is assured.

Measures to address the misalignment and lack of transparency of incentives in the securitisation market include strengthening the capital requirements for exposures, as well as introducing risk management practices and disclosures. These measures have already been agreed and will be implemented in the course of 2010. As improving economic conditions may lead to the resumption of securitisation activity, the measures taken will ensure that it is relaunched on a sounder and more sustainable basis.

Finally, work is under way to ensure that all systemically important institutions, markets and instruments are subject to adequate regulation and oversight. As a first step, a report will be issued in November by the IMF, the FSB and the BIS that will provide guidance on identifying systemically important institutions, markets and instruments.

I started this speech by briefly describing why banks are special. The last two years have painfully stressed how special and important they really are. When the financial system fails, the whole economic system is affected. The financial sector has undergone an unprecedented wave of innovation, change, consolidation and now crisis. We now have a better understanding of the business models that may not be sustainable, but there are still many open questions. For example, will future capital requirements provide banks with better loss bearing capabilities and the economic system with less procyclicality? How can future compensation and corporate governance principles support the long term value creation of banks? And, how can risk management practises and risk pricing models better represent possible gains and losses? Overall, there seems to be no simple answer on banks’ best practises and their business model. Therefore, we need the contribution of the academic community for the future design of banks’ business models and for the policies supporting them. I am – of course - already looking forward to this conference providing some answers to the important questions at stake.

-

[1] I would like to thank Florian Heider, Manfred Kremer and David Marqués Ibañez for their valuable input.

-

[2] X. Freixas and J. C. Rochet (1997), The Microeconomics of Banking, MIT Press.

-

[3] X. Freixas and J. C. Rochet (1997), op. cit.

-

[4] R. Kroszner and R. Rajan (1994), "Is the Glass-Steagall Act Justified? A Study of the U. S. Experience with Universal Banking before 1933", American Economic Review.

-

[5] In addition, recent evidence suggests that there are indeed conflicts of interest in banking that are not anticipated by the public. Investment banks affiliated with financial conglomerates take positions in takeover targets before the conglomerate announces its bid. Moreover, it appears that these inside trades are profitable, while the M&A deals are not wealth-creating. See A. Bodnaruk, M. Massa and A. Simonov (2009), “Investment Banks as Insiders and the Market for Corporate Control”, Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

-

[6] See Banking Supervision Committee (2009), “EU Banking Structures Report”, forthcoming in October.

-

[7] A. Shleifer and R.W. Vishny (2009), “Unstable Banking”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper Series No 14943.

-

[8] ECB (2008), Euro Money Market Survey.

-

[9] For an analysis see Heider, F., M. Hoerova and C. Holthausen (2009), “Liquidity Hoarding and Interbank Market Spreads: The Role of Counterparty Risk”, ECB Working Paper (forthcoming).

-

[10] Washington Mutual, the largest S&L institution in the United States, was seized by the FDIC and sold to JPMorgan Chase. At the same time, negotiations on the TARP rescue package stalled in the US Congress. Over the weekend, it was reported that British mortgage lender Bradford and Bingley had to be rescued, and the Benelux countries announced the injection of €11.2 billion into Fortis Bank. On the following Monday, Germany announced the rescue of Hypo Real Estate and Iceland nationalised Glitnir.

-

[11] A. Demirguc-Kunt and H. Huizinga (2009), “ Bank Activity and Funding Strategies: The Impact on Risk and Return”, CEPR Discussion Papers 7170, February.

-

[12] A. Beltratti and R. M. Stulz (2009), “Why Did Some Banks Perform Better During the Credit Crisis? A Cross-Country Study of the Impact of Governance and Regulation”, Charles A. Dice Center Working Paper No 2009-12, July.

-

[13] On this, see for example R. Gropp and F. Heider (2009), “The Determinants of Bank Capital Structure”, Review of Finance, forthcoming.

-

[14] For further information on macroprudential issues, see A. Crockett, “Marrying the micro- and macro-prudential dimensions of financial stability”, remarks before the Eleventh International Conference of Banking Supervisors, held in Basel on 20-21 September 2000. See also the Report of the High-Level Group on Financial Supervision in the EU chaired by Jacques de Larosière, in Brussels, on 25 February 2009. In the European Union, following the publication of the Report of the de Larosière Group, the European Commission proposed in May 2009 a set of ambitious reforms, including the creation of a new European Systemic Risk Board responsible for macro-prudential oversight. The European Council in June 2009 supported the European Commission’s proposal.

Европейска централна банка

Генерална дирекция „Комуникации“

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Възпроизвеждането се разрешава с позоваване на източника.

Данни за контакт за медиите