Forward guidance and policy normalisation

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, 17 September 2018

Forward guidance has become a valuable and effective policy instrument in central banking over recent years. There is by now compelling international evidence confirming that forward guidance has been successful in boosting growth and inflation outcomes by steering future interest rate expectations while central banks have been constrained in their policy space.[1]

More recently, some central banks, including the ECB, have also started to use forward guidance when heralding the transition out of a phase characterised predominantly by the use of non-standard monetary policy measures. In my remarks this morning I would like to explain why the need for policymakers to enhance transparency increases at times when past policy regularities may offer less guidance, or when the inflation outlook is surrounded by exceptional uncertainty.[2]

In these circumstances, forward guidance may not only be helpful, but also highly effective in reducing unwarranted uncertainty. I will show evidence that this claim holds true for the enhanced forward guidance that the ECB’s Governing Council delivered at its June monetary policy meeting.

In the future, there might be a case for the Governing Council to extend its current forward guidance beyond the timing to lift-off. If warranted, I will argue that this should be done by further clarifying policymakers’ reaction function rather than publishing a numerical forecast of the future path of short-term interest rates.

Forward guidance on the timing to interest rate lift-off

Let me start with a simple observation.

On my first slide you can see the textbook case for the need of a central bank to embark on unconventional policy measures. The usual caveats aside, until recently the prescriptions of simple Taylor-type policy rules have systematically been below actual short-term money market rates.[3]

To fill this policy void, in July 2013 the ECB started to use state-contingent forward guidance that has contributed to reducing both interest rates, including at longer tenors, and the sensitivity of money market rates to macroeconomic and political news. This eased financial conditions and insulated them from external shocks that would have otherwise resulted in an unwarranted tightening.[4]

Starting in June 2014, forward guidance has been complemented by a series of credit easing measures that have also entailed large-scale asset purchases and the adoption of negative interest rates. Empirical evidence confirms that these measures have jointly provided substantial additional policy accommodation that has been instrumental in securing a return of inflation to levels closer to 2%.[5]

What my first slide also suggests, however, is that recently – judging from these simple rule prescriptions – the policy gap has vanished as the growth and inflation outlook has improved. In fact, there is now a striking consistency between simple Taylor-type policy rule estimates and the actual level of money market rates, both current and projected. In other words, one may conclude from this chart that there is no longer a need for policymakers to resort to forward guidance as a means to provide the monetary stimulus that would be consistent with simple benchmark prescriptions.

Of course, central banks do not follow simple policy rules in practice. But the chart nevertheless raises the legitimate question of why the Governing Council, at its June monetary policy meeting, decided to be more explicit about its expectations for the timing to interest rate lift-off. After all, in the past major central banks typically did not issue any specific guidance on the timing and pace of future rate hikes.[6]

As you will certainly remember, during past upswings ECB guidance was limited to signposting and to the use of a few key words in the introductory statement to the press conference.[7] “Vigilance” and “monitoring closely” will always remain terms associated with that era of ECB policymaking.

Central banks rather signalled future policy intentions implicitly, by revealing information other than the future policy path – most notably, information about the economic outlook and the broader monetary policy strategy, including an arithmetic definition of price stability that could serve as a long-term nominal anchor for the economy.[8]

This approach to communication and transparency reflected the risks inherent in any type of explicit forward guidance: that such guidance could crowd out the important diversity of market views, thereby aggravating the risks of herding, and that it could potentially be taken by outsiders as an unconditional commitment.[9]

Our experience with forward guidance has at times confirmed this risk, although its benefits have by far exceeded its costs. Too often, academics and market participants have interpreted forward guidance as Odyssean, while for policymakers it can only be Delphic.

The case for the ECB’s enhanced forward guidance

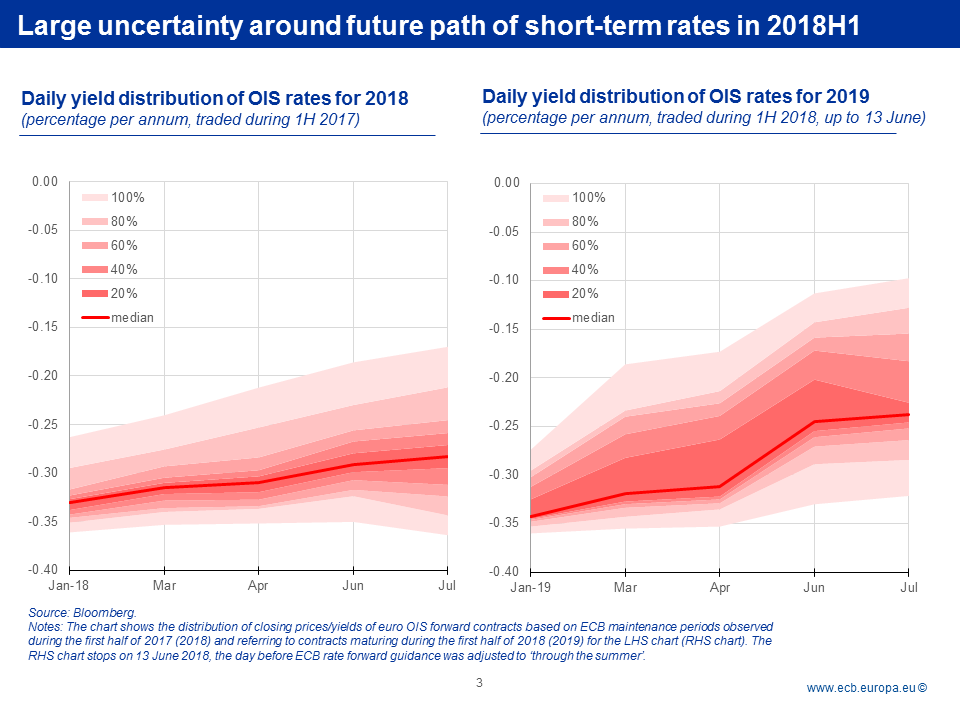

Why then didn’t the Governing Council decide, in June 2018, to simply return to the well-tested pre-crisis framework of managing expectations when there was no longer a need to provide additional policy accommodation? Here it is useful to first consider the market environment we were facing during the first half of this year and up until the 13 June Governing Council meeting. You can see this on my second slide.

What you can see here is that, compared to a year earlier, uncertainty around the future path of short-term interest rates had increased measurably. In the first months of this year, markets believed that an unusually wide range of policy outcomes would be possible in 2019.

A dispersion of views is not in itself a bad thing, of course. It is usually an encouraging sign that markets remain attentive to changes in the outlook. The information-processing role of markets can in fact be expected to recover during periods of policy normalisation. Herding, by contrast, is often a sign of perilous complacency.

A dispersion of views does become a source of concern, however, if it reflects uncertainty around the central bank’s reaction function. Such uncertainty is not unusual in periods of transition. Once policy has succeeded in shifting upwards the distribution of risks around the growth and inflation outlook, uncertainty about the future path of interest rates naturally begins to increase.

I would argue, however, that our environment is characterised by two factors that vindicate the need for stronger forward guidance and that have contributed to amplifying uncertainty around our near-term policy intentions.

The first has to do with the peculiar anatomy of the inflation process we are currently facing.

Although uncertainty around the inflation outlook is receding and a sustained convergence of inflation to levels closer to our aim is in sight, underlying inflationary pressures have long proven stubbornly weak – to an extent that, in the past, threatened to destabilise public confidence in the return of inflation to levels closer to 2%.[10]

In addition, there is still considerable uncertainty as to whether the key parameters underlying our workhorse Phillips curve models have undergone structural change – whether inflation has become less responsive to economic slack, be it through globalisation, technological progress or structural product and labour market reforms.[11]

At a time when policy rates remain deeply in negative territory, such parameter and model uncertainties imply that the costs of committing a type II error – of failing to anticipate a much slower than usual return of inflation to pre-crisis levels – may be uncomfortably high.

Communicating our expectation that the ECB key interest rates would remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019 was therefore consistent with the “risk management” approach to monetary policy that the Governing Council has repeatedly applied in recent years, including in our earlier decisions to clarify our reaction function or to change our policy stance pre-emptively in the face of tail risks.[12]

The second factor that has called for more transparency around our policy intentions relates to the effects of unconventional monetary policy measures. Unwinding policy accommodation in a multi-dimensional policy space is terra incognita for both financial markets and policymakers.

For this reason, the Governing Council started a long time ago to communicate its expectation that the key ECB interest rates would remain at their present levels for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases. Transparency about the envisaged sequence in the adjustment of our various policy instruments was an important element of our communication strategy.

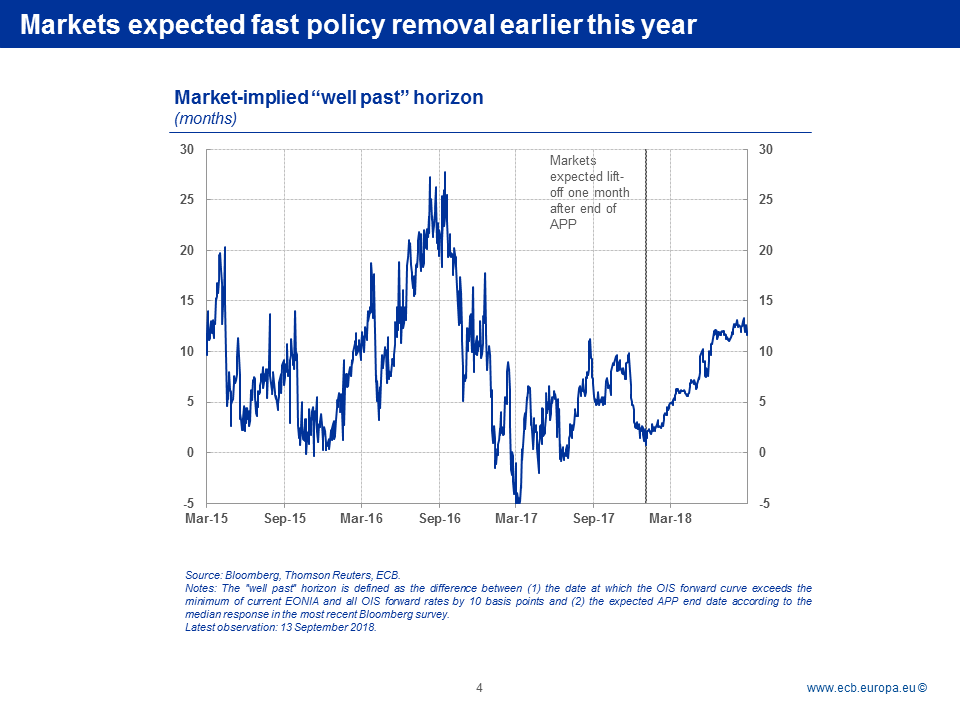

Yet, on my next slide you can see that, at some point in early 2018, markets expected the ECB to hike its deposit facility rate one month after the expected end of net asset purchases. Given our previous indications, and the experience of other central banks, this was an extraordinarily early expectation, in particular as changes to our key policy rates would have affected the entire term structure of interest rates.[13]

In other words, the slide suggests that gradual progress towards a sustained convergence in the path of inflation increasingly injected volatility into the expected future rate path.

We therefore judged that more clarity on the timing to lift-off could help condense the focus of market uncertainty from two variables – the end-date of asset purchases and the definition of “well past” – to one variable – “at least through the summer” – which the Governing Council could more easily control with its communication.

On my next slide you can see that our enhanced forward guidance has been effective in reducing uncertainty around the short end of the EONIA forward curve. Shortly after our press conference on 14 June there has been a notable compression in the option-implied densities around three-month EONIA forwards. Dispersion around the median expected path has become much more condensed.

Guidance on the future path of short-term interest rates

Now, communication about lift-off expectations is, of course, only a first step in managing the transition towards policy normalisation. A natural question to ask, then, is: should policymakers also provide guidance on the envisaged subsequent path of future short-term interest rates and, ultimately, on the expected level of the terminal rate, and if so, how?

There are two broad ways in which central banks can increase transparency around the future path.

The first is to publish policymakers’ projection of the future path of short-term interest rates conditional on the macroeconomic outlook.[14] The second approach is to broadly maintain within the confines of current practice, which is geared towards explaining in more detail the central bank’s reaction function and to communicate policymakers’ conditional expectation of the likely future pace of policy adjustment. The key difference between the two approaches is, hence, the level of precision with which policymakers are willing to communicate their future policy inclinations.

The first approach is by no means uncharted territory in the central banking community. A number of pioneering central banks, led by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1997, regularly publish numerical interest rate forecasts to reinforce their inflation targeting commitment, very much in line with modern monetary theory.[15] And, in 2012, the Federal Reserve started publishing FOMC participants’ assessments of the appropriate future policy rate, in the form of the “dot plot” in the Summary of Economic Projections.

The experience of these central banks shows that there have been many instances where guidance on the future path has been successful in coordinating disperse market views.[16] But there have also been instances of stark and persistent discrepancies between the path expected by market participants and that published by policymakers.[17]

Some academics have resolved this impasse by arguing that the optimal degree of transparency depends on the central bank’s ability to forecast the economy.[18] Put simply, transparency around future policy intentions is likely to be welfare enhancing if the central bank has established a convincing track record of systematically beating private sector inflation forecasts.

But neither the private sector nor central banks have been particularly good recently at predicting inflation. More, even a well-established projection track record may not be enough to tilt the balance in favour of publishing a path for future policy – mainly for four, largely interrelated, reasons.

First, it is often more important how central banks communicate than what they communicate. Back in 2004, Alan Blinder already pointed out that a monetary policy committee that releases dispersed views could cause a “cacophony” in communication and ultimately create more confusion than clarity.[19]

Indeed, I believe that one reason why the ECB’s enhanced forward guidance has been so effective is precisely the fact that it represents the Governing Council’s unanimous view.

For a large committee to agree on an entire path of future policy rates is, however, a completely different endeavour and unlikely to be possible in practice, in particular when global uncertainty severely clouds the medium-term outlook.[20] Incidentally, most market criticism of the Federal Reserve’s dot plot focuses on the fact that the dots represent individual views rather than the committee’s joint assessment.[21]

Second, even a credible interest rate path may cause misperceptions. Consider the current market environment that is characterised by regulatory-driven demand for high quality liquid assets and large securities holdings by central banks.

One tangible consequence of these two factors is an increased demand for safe assets that has led to substantial and unprecedented negative term premia at the short end of the curve.

This means that the path for rates truly expected by investors is likely to be materially higher than that suggested by plain forward rates. This greatly complicates the clarity of any guidance on the future path.

A very simple way to see this is to compare market-based and survey-based expectations. You can see this on my next slide, where the grey shaded area represents the difference between the median fed funds rate projections in the New York Fed’s Survey of Primary Dealers and the nominal fed funds futures rates.

Clearly, a good part of the discussion around this gap would vanish if the signals extracted from market prices were treated more carefully. The chart shows a snapshot of the situation earlier this year, but the argument holds more widely.

A third source of confusion, specific to the ECB, relates to the policy rate the central bank should provide a numerical path for.

In the current environment of large excess liquidity the deposit facility rate is de facto our key policy rate. But charting its future path would be complicated by the endogenous impact of changes in excess liquidity on its level. At longer tenors in particular, it would be difficult for markets to disentangle the fraction of the path that reflects a genuine change in policy rates from that reflecting changes in excess liquidity.

Numerical guidance on our main refinancing rate, by contrast, might be of little value to market participants at shorter horizons, unless we were to convey, in parallel, information on the expected width of the rate corridor. In fact, one might even argue that would the Governing Council decide to publish a path for future interest rates, it would have to anticipate decisions on the ECB’s long-term operational framework, such as whether we intend to retain the pre-crisis framework of steering short-term rates within an interest rate corridor or whether we plan to adopt a floor system. These are important decisions that need time and careful deliberations.[22]

Finally, it is difficult to communicate about a concept on which the central bank itself has little or poor information, such as the “terminal rate”, or the neutral level of the policy interest rate that is expected to prevail once all shocks have dissipated.

It is a well-known fact that estimates of the natural rate of interest, commonly referred to as r*, are highly uncertain no matter which approach is used. For example, the Holston-Laubach-Williams estimate of the US natural rate could currently be anywhere between -3% and +5%.[23] The same uncertainty applies to estimates of natural rates in other economies, including the euro area.[24]

So, all in all, a central bank needs to carefully weigh these risks against the potential benefits of publishing a numerical forecast of the future policy rate path.

I would argue, however, that the second option I mentioned earlier for providing guidance on the future path, if warranted, might help overcome many of these risks. That is, rather than publishing a full numerical interest rate path, policymakers may continue to signal their inclinations by clarifying their reaction function, even in the period of instrument normalisation.

For example, state-contingent forward guidance could clarify the pace with which policymakers expect to remove policy accommodation beyond the timing to lift-off. Such guidance can help improve policy predictability, while avoiding the pitfalls that precise numerical guidance on the future path of short-term interest rates might entail.

One of the benefits of this type of forward guidance is that it remains a product of the economic conditions that give rise to it – in other words, it remains Delphic, as it has always been. Should those conditions change, policymakers may reformulate or repeal the guidance altogether.

Forward guidance linked to specific economic regimes – “Aesopian” forward guidance as it has recently been dubbed – has also been found to be more effective.[25] Empirical evidence suggests that the public tends to pay more attention to policy signals in unusual economic circumstances than during normal times.[26]

This is certainly our experience with forward guidance in the current uncertain environment but it also suggests that, in the future, given the complexity of chartering a multidimensional policy space, a further clarification of our reaction function might help market participants and the broader public to better anticipate the likely future path of short-term interest rates.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that the enhanced forward guidance that the Governing Council adopted in June 2018 has been effective in reducing uncertainty around the expected future path of short-term interest rates. It has helped to preserve the current accommodative financial conditions on which the sustained convergence of inflation to levels that are below, but close to, 2% over the medium term is based.

Looking ahead, should economic conditions warrant, there might be a case for the Governing Council to go beyond the timing to lift-off in further clarifying the pace at which it expects to remove policy accommodation. In the euro area context, I believe that the risks of publishing a precise numerical forecast of the future path of policy rates are, however, likely to outweigh the benefits.

Thank you.

- [1]See e.g. Campbell et al. (2016), "Forward Guidance and Macroeconomic Outcomes since the Financial Crisis," NBER Macroeconomics Annual 31 (2016), pp. 283-357; and Charbonneau, K.B. and L. Rennison (2015), "Forward Guidance at the Effective Lower Bound: International Experience," Bank of Canada Discussion Papers, No 15-15.

- [2]Today’s remarks focus on rate forward guidance and abstract from forward guidance on the future size and composition of the central bank’s balance sheet.

- [3]Simple estimated policy rules suffer from two important caveats. First, they do not capture the two-way feedback between monetary policy and the economy. Second, they are predicated on pre-crisis constant natural rates of interest, while empirical analyses indicate that the natural rate is likely to have declined since then.

- [4]See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Central bank communication in a low interest rate environment”, Open Economies Review, Vol. 28, Issue 5, pp. 813-822; and European Central Bank (2014), “The ECB’s forward guidance”, Monthly Bulletin, April.

- [5]See e.g. Altavilla, C., G. Carboni and R. Motto (2015), “Asset purchase programmes and financial markets: lessons from the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No 1864; Andrade, P., J. Breckenfelder, F. De Fiore, P. Karadi and O. Tristani (2016), “The ECB's asset purchase programme: an early assessment”, ECB Working Paper No 1956; and Blattner, T.S. and M. Joyce (2016), “Net debt supply shocks in the euro area and the implications for QE”, ECB Working Papers, No 1957.

- [6]A notable exception was the Federal Reserve’s forward guidance introduced in May 2004, to which I will refer later in my remarks. The Federal Reserve’s date-based guidance issued in 2011 was of more “conventional” nature as it was used in the face of increasing downside risks to the economic outlook. For an overview, see Moessner, R., D. J. Jansen and J. de Haan (2017), “Communication About Future Policy Rates in Theory and Practice: A Survey”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, Issue 3, pp. 678-711. For date-based guidance, see Raskin, M. (2013), “The Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Date-Based Forward Guidance”, Federal Reserve Board, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, No. 2013-37.

- [7]Back in 2006, then ECB President Trichet noted that “the ECB does not embark on a particular multi-monthly pre-commitment on interest rates or on the path of future policy interest rates”. See Trichet, J.C. (2006), “Monetary Policy and Economic Prospects in the Euro Area”, speech at the Institute of Economic Affairs conference on “The State of the Economy: Overcoming Key Challenges to Sustainable Economic Growth”, London, 6 February.

- [8]See, for example, Blinder, A.S., M. Ehrmann, M. Fratzscher, J. De Haan and D. J. Jansen (2008), "Central Bank Communication and Monetary Policy: A Survey of Theory and Evidence", Journal of Economic Literature, 46 (4), pp. 910-45.

- [9]See Morris, S. and H. S. Shin (2002), “Social Value of Public Information”, American Economic Review, 92 (5), pp. 1521–1534; and Mishkin, F. (2004), “Can Central Bank Transparency Go Too Far?”, NBER Working Papers, No 10829.

- [10]On a bigger scale, this relates to an issue I have commented upon extensively in recent times: the threat of hysteresis. See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Scars or scratches? Hysteresis in the euro area”, speech at the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, 19 May; and Cœuré, B. (2018), “Scars that never were? Potential output and slack after the crisis”, speech at the CEPII 40th Anniversary Conference, Paris, 12 April.

- [11]See, for example, Dotsey, M., S. Fujita and T. Stark (2017), "Do Phillips Curves Conditionally Help to Forecast Inflation?," Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Papers, No 17-26; and IMF (2017), “Recent wage dynamics in advanced economies: drivers and implications”, IMF World Economic Outlook, October.

- [12]See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Central banks as risk managers”, speech at the 53rd SEACEN Governors’ Conference/ High-Level Seminar and the 37th Meeting of the SEACEN Board of Governors, Bangkok, 16 December. See also Powell, J.H. (2018), “Monetary Policy in a Changing Economy”, speech at the symposium "Changing Market Structure and Implications for Monetary Policy", sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 24; and Greenspan, A. (2004), “Risk and Uncertainty in Monetary Policy”, speech at the Meetings of the American Economic Association, San Diego, California, 3 January.

- [13]One reason for the formation of such expectations might have related to the growing appreciation of the strength of the stock effect of central bank asset purchase programmes. See Cœuré, B. (2018), “The persistence and signalling power of central bank asset purchase programmes”, speech at the 2018 US Monetary Policy Forum, New York City, 23 February.

- [14]This could be done with or without confidence bands signalling the uncertainty around the central projection.

- [15]See, for example, Woodford, M. (2003), Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy, Princeton University Press. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was followed by the Norges Bank in 2005 and the Sveriges Riksbank and the Bank of Israel in 2007, and a few others thereafter.

- [16]See, for example, Bongard et al. (2016), “Connecting the dots: market reactions to forecasts of policy rates and forward guidance provided by the Fed”, DNB Working Papers, No 523; and Brubakk, L., S. ter Ellen and H. Xu (2017), “Forward guidance through interest rate projections: does it work?”, Norges Bank Working Papers, No 6-2017.

- [17]The case of the Riksbank in 2011 is probably the most prominent example in this respect. See Svensson, L.E.O (2014), “Forward Guidance”, NBER Working Papers, No 20796.

- [18]See, for example, Walsh, C. E. (2007), “Optimal Economic Transparency”, International Journal of Central Banking 3 (1), 5–36.

- [19]See Blinder, A. S. (2004), The Quiet Revolution in Central Banking Goes Modern, Yale University Press.

- [20]For the difficulties of committees in agreeing on a path of future interest rates, see also Blinder, A., C. Goodhart, P. Hildebrand, D. Lipton and C. Wyplosz (2003), “How Do Central Banks Talk?”, Geneva Reports on the World Economy, No 3.

- [21]See, for example, Olson, P. and D. Wessel (2016), Improving The Fed’s Dots, The Brookings Institution.

- [22]See Cœuré, B. (2016), “The ECB's operational framework in post-crisis times”, speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 40th Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, 27 August.

- [23]See Fiorentini, G., A. Galesi, G. Pérez-Quirós and E. Sentana (2018), “The Rise and Fall of the Natural Interest Rate”, Banco de España Working Papers, No 1822.

- [24]See Fries et al. (2017), “National natural rates of interest and the single monetary policy in the Euro Area”, Banque de France Working Papers, No 611.

- [25]See Moessner et al. (2017, op. cit.).

- [26]See, for example, Nimark, K. P. (2014), “Man-bites-dog business cycles”, American Economic Review 104(8): 2320-2367; and Woodford, M. (2005), “Central-bank communication and policy effectiveness”, paper presented at the FRB Kansas City Symposium on “The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future,” Jackson Hole, WY, August 25-27.

Europeiska centralbanken

Generaldirektorat Kommunikation och språktjänster

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Texten får återges om källan anges.

Kontakt för media