The evolving risk landscape in the euro area

Speech by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at the Banco de Portugal Conference on Financial Stability, Lisbon, 17 October 2017

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am grateful for the opportunity to address you today at this relevant conference on financial stability and macroprudential policy and particularly pleased for doing it at a place I consider my alma mater of central banking.

The world economy is going through a period of sustained moderate growth. In particular, the cyclical recovery in the euro area is now stronger and broad-based, driven by a virtuous circle of employment creation and private consumption. All member countries are experiencing economic growth, the significant current account deficits at the beginning of the crisis in various countries have turned into surpluses, and in public finance most countries previously under stress are now showing positive primary surpluses. Since mid-2013, almost seven million jobs have been created, offsetting the losses during the peak of the crisis and unemployment is at its lowest level since 2008, albeit still quite high. Business confidence is the highest in a decade suggesting that we can expect a continued and resilient recovery in the coming quarters. These developments were and are still strongly supported by the ECB’s expansionary monetary policy after the second recession in 2012-2013.

Notwithstanding these developments, there are concerns regarding possible financial instability stemming from international market developments that could lead to price corrections. Signs of general overvaluation in asset prices are however not present in the euro area. There are localised asset price pressures in a few national housing markets and, in particular, in the commercial property market. As a result, several countries have adopted macroprudential policies and are dealing successfully with those tensions.

The overall financial stability situation in the euro area is therefore positive and well underpinned by the improved fundamentals of our economies. Improvements indicate that the euro area is now much more resilient and better prepared to cope with potential financial shocks that may very well happen in the near future.

The more significant risk in the horizon is a possible reversal of risk assessment in international financial markets with the consequent asset price downward corrections. The ensuing capital losses incurred by asset holders, including many financial institutions, would have negative wealth and demand effects. The increase in bond yields would put pressure on the more indebted economic agents. Part of the possible price corrections are however associated with the improved economic situation that will eventually lead to higher nominal growth, thus contributing to debt sustainability.

One of the suggested triggers of market corrections is the recalibration of monetary policies that is gradually starting to take place in different degrees across important jurisdictions. There are two points worthwhile making in this respect. The first is that, in spite of being widely predicted in market commentary, very little is happening in financial markets to anticipate it. Market participants who are supposed to be forward looking, do not seem to anticipate material changes in asset prices. The second is that this disconnect between market commentary and concrete market decisions, could indicate that the simple recalibration of monetary policies is expected to be smoothly absorbed without generating undue turbulence. Naturally, for this to be possible, monetary policy recalibration must be quite gradual. That will be the case of the ECB as we have already said that anyhow “monetary policy will continue to be very accommodative” until we achieve our goals. If central banks adopt cautious strategies, then presumably only a significant geo-political event could trigger more material changes in financial and economic conditions. Nevertheless, one knows that markets are unpredictable and can overshoot, especially in situations like the present one with many risks and a protracted period of very low volatility in asset prices.

In the remainder of my remarks today, I will address the evolution of the pricing of risk in the equity and bond markets during the crisis and its aftermath. This will provide the rationale for the drivers of the possible incoming changes. I will then reflect on the consequences for the different asset markets and their respective impact on the various economic agents. I will end with a brief analysis of what macroprudential policies can do and are doing to safeguard financial stability in the euro area.

Behaviour towards risk

As expected, the crisis led to a significant rise in risk aversion and a generalised preference for safety. The depth of the crisis has left behind profound scars not only in the economies’ productive capacity but also in the minds and behaviour of economic agents concerning risk. The memory of the unexpected materialisation of tail risks lingers. The preference for safety is partly responsible for the excess demand for safe assets, for the increase of the equity risk premium, for the reluctance to invest in real productive assets and for the persistent sluggishness of wages. The elasticities of wage response to the economic slack and of consumption and investment reaction to the cost of finance have both declined. As a result, the wage Phillips curve became flatter and the Investment-Saving (IS) curve has become steeper. Several factors contributed, of course, to this development, in particular, increased inequality contributes to explain higher savings and lower consumption while shrinking investment opportunities linked to secular stagnation explains lower investment.

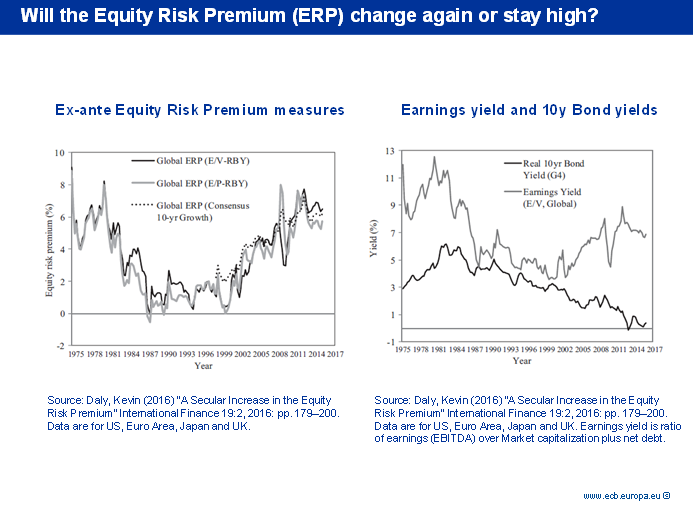

According to the general risk return trade-off, it was to be expected that investors would demand higher returns to hold riskier assets. This can be illustrated by examining the evolution of the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) – the excess return that investing in the stock market provides over a risk-free rate – in advanced economies (Figure 1)[1] which implied an increase in the cost of equity

Figure 1

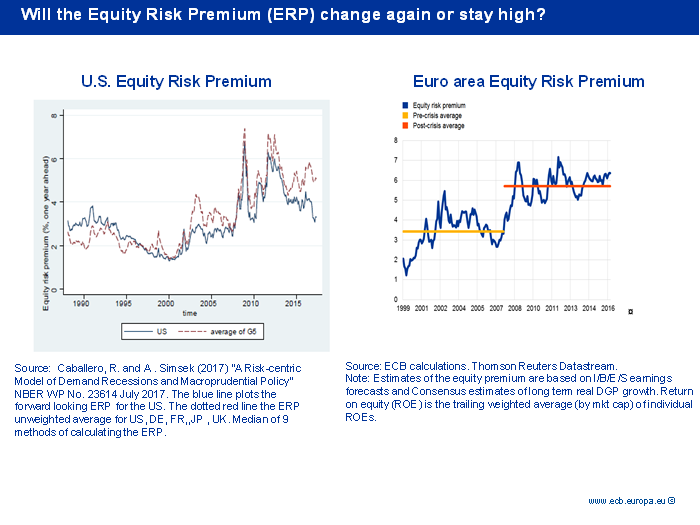

The upward trend in the ERP began already in 2000 in the wake of the Dot-com stock crash (Figure1, left-hand side (LHS)). The ex-ante ERP is the difference between the required stock returns and the risk free rate. By depicting the two components, it becomes clear that the increased ERP resulted both from an increase in the Earnings Yield (EY) and a sharp decline in the risk free rate (Figure 1, right-hand side (RHS)). Note however the more recent EY decrease (which corresponds to the inverse of the Price-Earnings (P/E) ratio). This is already reflected in the recent decrease of the ERP in the U.S. (Figure 2)[2].

Figure 2

The two relevant factors contributing to the decline of the risk free rate were the “savings glut” of the early 2000s, identified by Bernanke (2005)[3] and the scarcity of “safe assets” underlined by Caballero and Farhi (2014)[4] after the crisis. Furthermore, expansionary monetary policies were also responsible for the decline in nominal interest rates and for the impact on yields and risky asset prices via rebalancing effects, resulting from Quantitative Easing (QE). As expansionary monetary policy attempted to reduce the output gap it also helped to fill the risk gap. In order to successfully avoid a big depression, monetary policy had to lower interest rates until the zero lower bound was attained. The changes in the IS and Phillips curves have rendered the task more difficult along the way and put pressure on monetary policy to adopt more unconventional measures.

More structural elements – related to the persuasive views on secular stagnation and the effects of globalisation on inflation – helped to consolidate the notion that the advanced economies are facing a protracted period of low growth and low inflation that central banks are failing to normalise but have to continue to address. Consequently, search for yield and trust in a sort of “central banks’ put” was the prevalent narrative until last year. Markets are becoming increasingly aware that central banks will not ensure such a put and are thus starting to recalibrate policy, not least as a result of the strong recovery now ongoing.

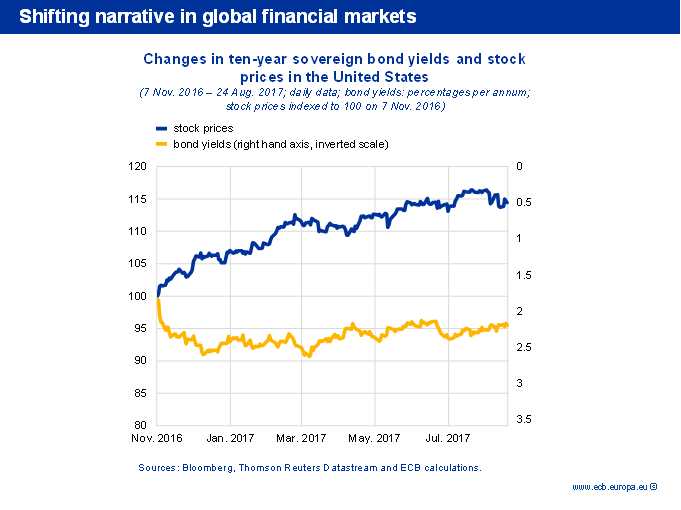

The U.S. elections of last November had already temporarily interrupted the market’s belief of the previous narrative. At the turn of the year, the perception was formed that tax cuts and deregulation would spur U.S. growth, which would increase earnings’ yields, subsequently leading to higher inflation and higher bond yields. Consequently, we saw the beginning of a rotation from bonds to stocks with a consequent increase in stock prices and a drop in bond prices (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Asset price developments

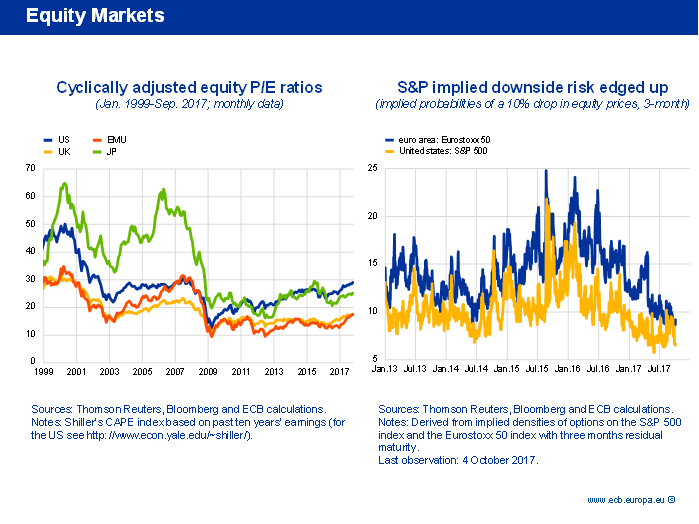

This narrative about a new reflation phase in the world economy petered out last spring, particularly in what regards bonds whose prices have slightly increased since. However, stock prices continued to increase, generating fears and warnings about a possible correction (Figure 3) especially in the U.S. where, contrary to the euro area, the cyclical adjusted price earnings is well above historical averages (Figure 4, LHS). There are already signs that markets are reflecting concerns with possible downward movements: the probability of a 10% correction in stock prices extracted from option pricing has recently increased albeit remaining quite low (see Figure 4, RHS) and the price of shortening the VIX has recently sharply increased.

Figure 4

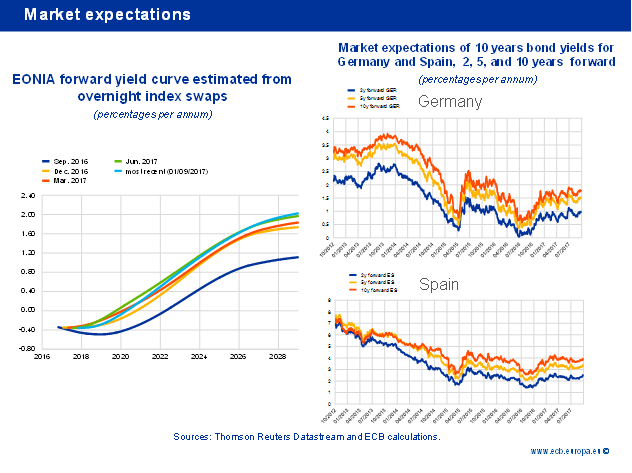

Nevertheless, we should ponder that equity market corrections are often not very consequential as the examples of 1987 or 2000 seem to indicate. In general, it is interest rates and fixed rate debt instruments that exert a wider financial and economic impact. As I mentioned before, there are no signs of significant changes in yields despite wide expectations of monetary policy recalibration around the globe. This presumably bodes well for future central banks’ decisions. Figure 5 shows the slow and smooth market expectations extracted from the OIS curve, for future EONIA for the euro area. The EONIA is expected to go above zero only in 2019 and reach 2% in ten years-time. On the other hand, market expectations of ten years German and Spanish sovereign bonds yields five years from now are respectively 1.5 and 3.3 and only move to 1.76 and 3.9 when assessed ten years from now (Figure 5, RHS). Indeed, markets expect 10 year bond rates to remain much lower than in the past for a long period of time.

Figure 5

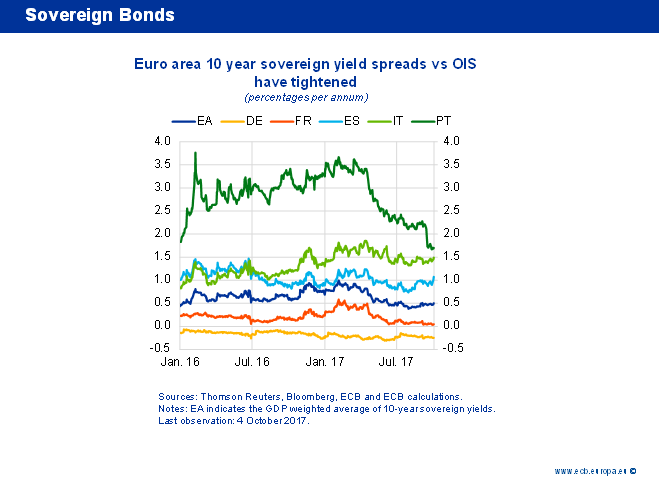

Yield and spreads of euro area countries’ sovereign debt have remained stable or even dropped with no signs of turbulence (Figure 6).

Figure 6

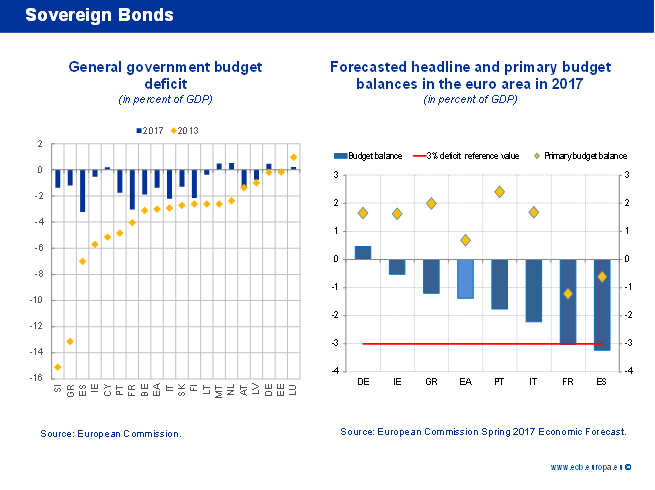

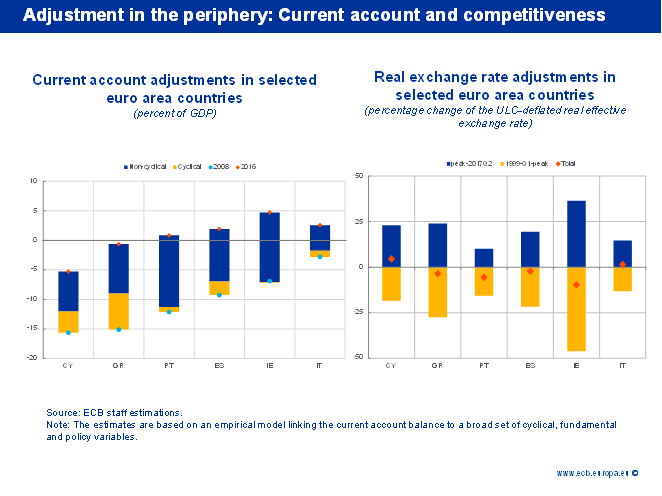

While these developments are supported by the ECB’s expansionary monetary policy, they also result from the deep adjustment undergone by the countries that were under stress during the crisis. The change in policies and the structural reforms implemented contributed to a notable reduction both in their external and fiscal imbalances. This has enhanced the overall resilience of the euro area against possible economic and financial shocks. Thanks to significant fiscal consolidation efforts, fiscal deficits across euro area countries have been reduced (Figure 7). The European Commission expects deficits below 3% of GDP and positive primary surpluses in almost all euro area countries in 2018.

Figure 7

The increased robustness of the euro area economy is also reflected in the gradual unwinding of the large current account deficits accumulated by several countries before the crisis. Practically all those countries are now showing a surplus and the adjustment was mostly of a structural nature (see the blue bars, Figure 8, LHS). This turnaround was achieved because the initial dramatic increases in the real exchange rates have largely been corrected (see Figure 8, RHS). In most former programme countries relative unit labour costs are now below their respective level in 1999. All these positive adjustments have certainly contributed to underpin the evolution of sovereign bonds.

Figure 8

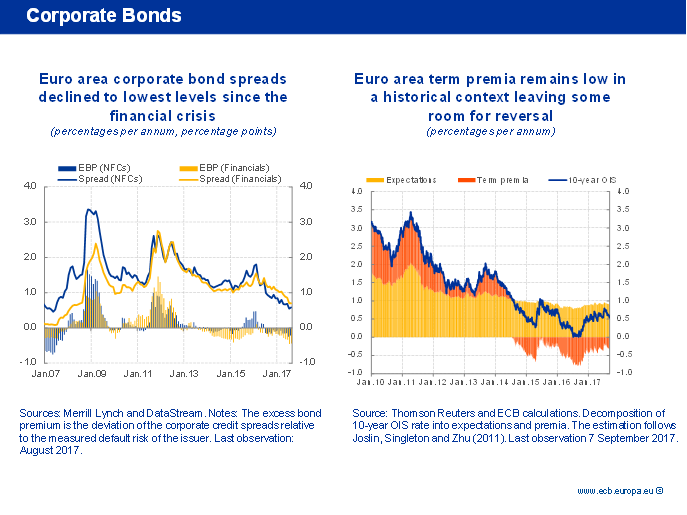

Likewise, corporate bond yields have continued to decline in the euro area (Figure 9 LHS, Figure 10 LHS for high yielders). Spreads for the debt of both euro area banks and non-financial firms relative to risk-free benchmarks have decreased significantly since the beginning of the year. Similarly to the U.S., this has reflected exceptionally low bond term premia (Figure 9, RHS). Compressed or even negative term premia may however point to potential significant corrections if events trigger a change in investors’ assessment of risk. Particularly, a revision concerning future inflation, no matter how unlikely, could lead to significant increases in term premia and higher yields.

Figure 9

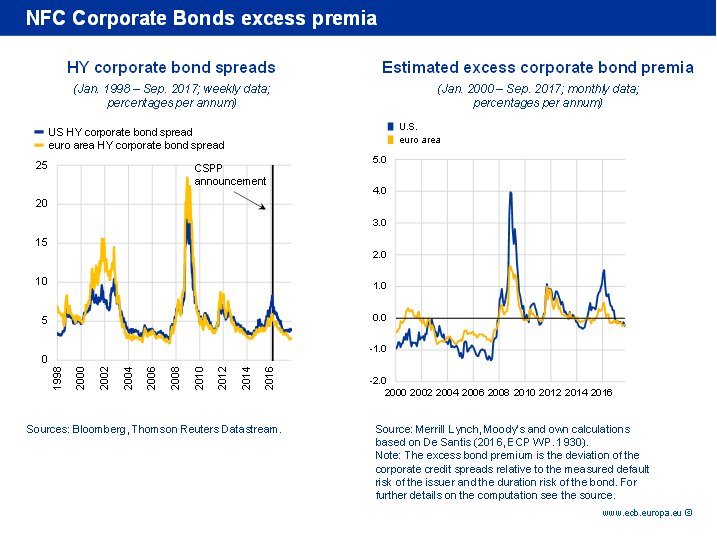

Nevertheless, taking into account the present market configuration and modelling fair value valuations, excess corporate bond premia in the euro area cannot be detected (Figure 10, RHS). The excess bond premium is given by the deviation of the corporate credit spreads relative to the measured default risk of the issuer and the duration risk of the bond. The estimates show that ‘excess premia’ have declined since end-2015 and are currently negative, implying that investors require no premium to hedge against adverse economic scenarios.

Figure 10

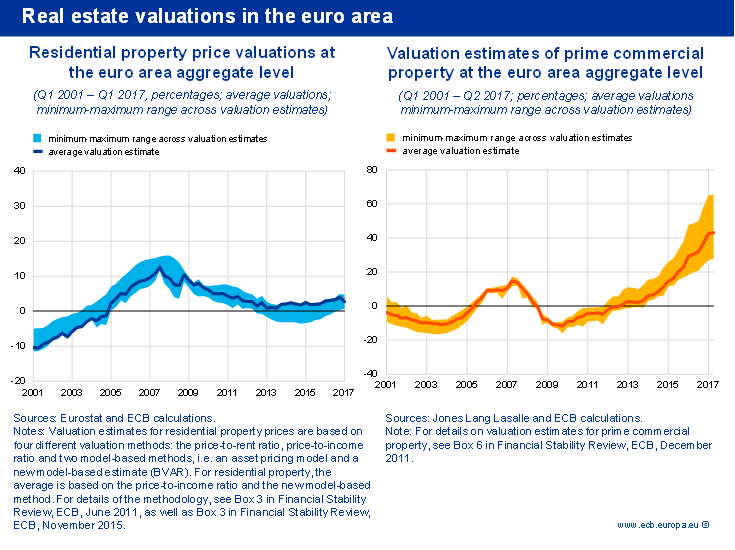

Looking now to another asset class, our analysis indicates that on the aggregate, residential property prices are broadly in line with the fundamentals, using various different methods to assess whether there are overvaluations in the market (see Figure 11). The situation is different in the case of commercial real estate. In specific areas and large cities, housing prices have however increased at a faster pace than households’ incomes and may show signs of overvaluation.

Figure 11

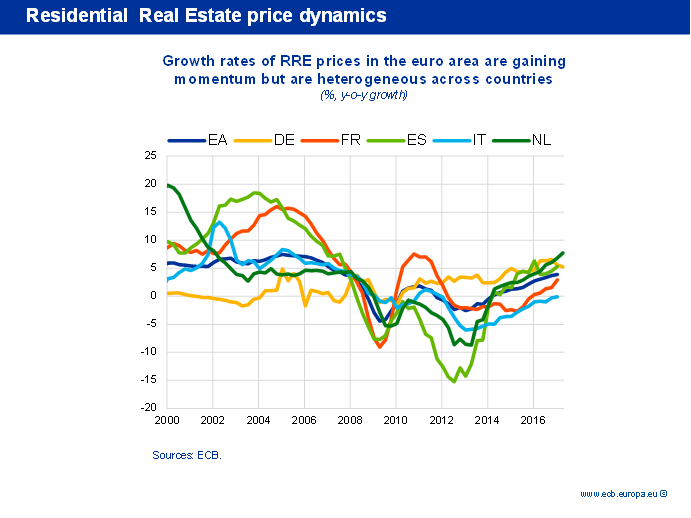

On the other hand, property prices and transaction volumes have grown strongly in recent years and have already reached historical highs in many euro area countries (see Figure 12). Nominal growth of residential property prices accelerated to around 4% y-o-y in Q1 2017 but remained below its historical average growth rate and well below pre-crisis values. In real terms, price increases moderated due to inflation picking up. Residential property prices are demand-driven and increasingly supported by the recovery in personal income which is expected to continue.

Figure 12

Potential impact of asset price shocks

The analysis of the situation in different asset markets illustrates that generalised overvaluation does not exist in the euro area. Tensions in some real estate markets are being dealt with by macroprudential instruments in many countries.

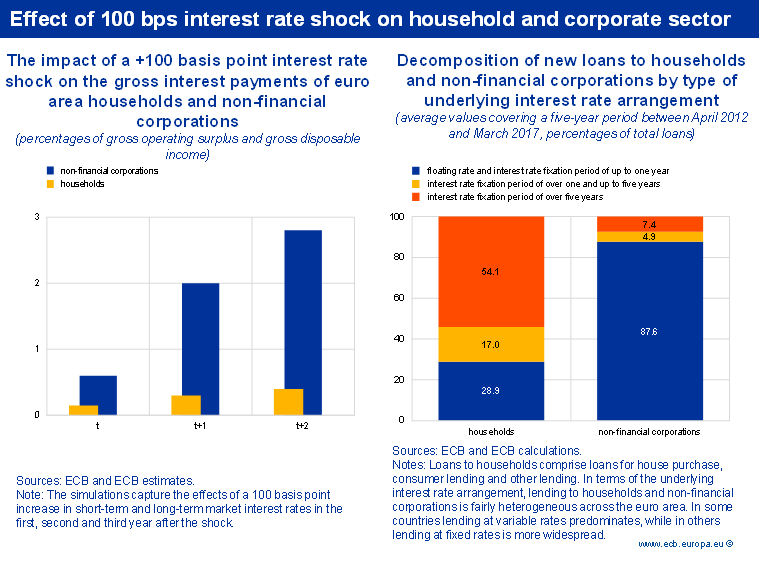

To assess possible financial stability risks we should however try to gauge the possible impact of the materialisation of an interest rate or yields correction. In the following paragraphs, I will explore the effects of such a shock calibrated at 100 basis points. Estimates suggest that the impact of this sizable increase on the non-financial private sector is relatively small, in particular for euro area households (see Figure 13, LHS). One reason lies in the interest rate fixation period of loans. Loans with floating rates or rates with rather short fixation periods are more widespread for euro area non-financial corporations. In contrast, the majority of newly demanded loans by households have longer interest rate fixation periods, making them more resilient against interest rate increases (see Figure 13, RHS). The estimates indicate that three years after the interest rate shock, the impact would represent a burden of 0.5% of household disposable income and about 2.5% of the gross revenues of non-financial firms, amounts that could be absorbed in the context of the ongoing recovery.

Figure 13

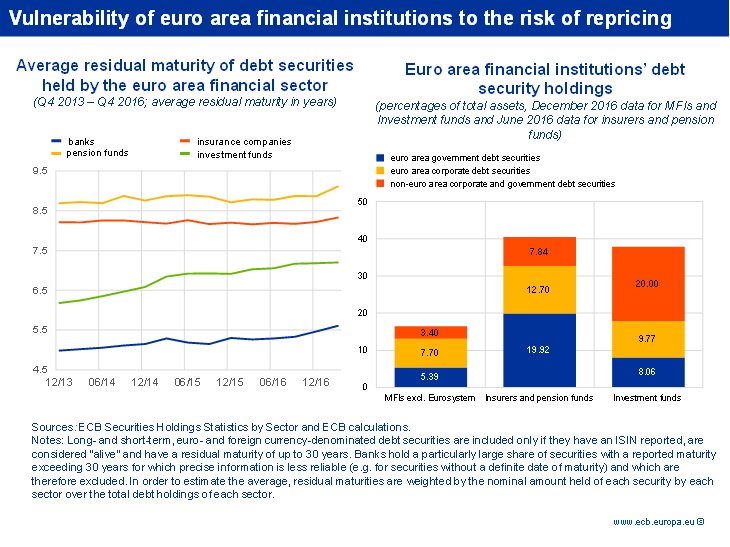

A sudden repricing in fixed income markets could lead to substantial capital losses for investors with large holdings of bonds. In the euro area, the impact would be felt in particular by the non-bank financial sector. For insurers and pension funds, bonds account for almost 40% of their portfolios. For banks, this share is only around 15% (see Figure 14 RHS). In addition, bond portfolio valuations have become more sensitive to changes in interest rates in recent years as duration has continued to increase (see Figure 14, LHS). Currently, a 100 basis point increase in interest rates would lower the value of outstanding securities by 7%, compared to 5% before the financial crisis. However, these simple metrics neither take into account any hedging arrangements nor the impact of any repricing on the value and cost of financial institutions’ liabilities.

Figure 14

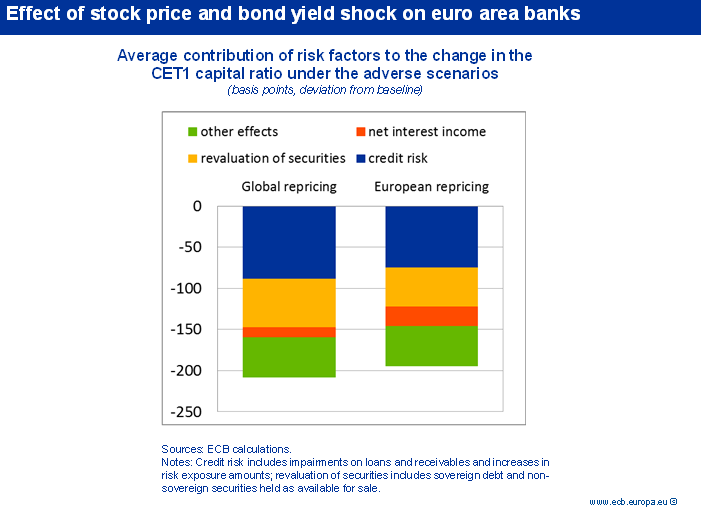

Regarding the overall impact on the significant euro area banks that are directly supervised by the ECB, Figure 15 updates estimates published in the ECB Financial Stability Review in May 2017. The estimates embody a whole range of effects: the capital losses on securities holdings (without considering any hedging), the increase in credit risk resulting from the estimated impact on probabilities of default of exposures, the corresponding effects on interest revenues and the broad impact on net interest income stemming from the increase in credit rates and funding costs of banks (deposits and wholesale funding).

The estimates are made for two scenarios. The global repricing scenario features, among other assumptions, an international increase in bond yields of 120 basis points and a 30% drop in stock prices. The European repricing scenario, induced purely by European developments, includes an average increase in bond yields of 75 basis points unevenly distributed across countries (no increase for Germany and more than 200 for some more vulnerable countries), accompanied by an average drop of 10% in equities. The outcome of the two scenarios indicates a negative impact on banks’ Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital hovering around 200 basis points in terms of deviation from the baseline scenario. This impact has to be considered against the comfortable present average CET1 ratio of 14% enjoyed by the euro area banks.

Figure 15

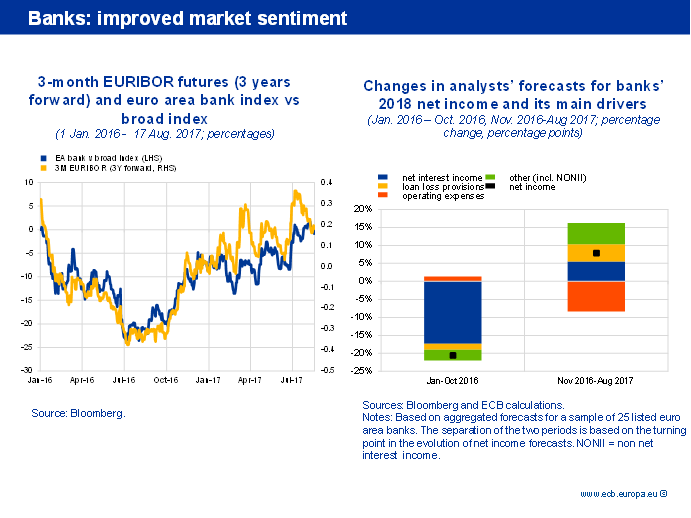

It is also important to recall that market sentiment towards euro area banks has continued to improve, despite some gyrations that broadly reflect developments in interest rate expectations (Figure 16, LHS). While contagion from the recent events of bank resolution and liquidation remained contained, these events have also highlighted the important challenges regarding the resolvability of weak banks. Notwithstanding some recent progress in non-performing loan (NPL) disposals, the large stock of NPLs remains a key structural concern in several countries. In addition, overcapacity and cost inefficiencies continue to weigh on bank profitability in certain banking markets.

The economic recovery, the expected steepening of the yield curve and even the progress being made in reducing the NPL level from the average peak of 8% in 2013 to the more recent average of 5.5%, have improved the market assessment of future banks’ profitability. Analysts’ earnings forecasts for 2017 and 2018 have been revised upwards since the U.S. elections, even if net interest income expectations have changed only marginally, despite improving economic conditions (volume effect) and (prospective) higher long-term interest rates (price effect). Analysts revised their earnings forecasts between October 2016 and January 2016 (see Figure 16 black dot in left bar) and between August 2017 and November 2016 (black dot in right bar) with the respective contributing factors. While forecasted net interest income was a drag on net income in the first period it contributed positively in the second period. Forecasted loan loss provisions contributed positively in the second period because they became less negative over the period November 2016 – August 2017 while forecasted operating expenses increased.

Figure 16

Macroprudential policy

Let me now turn to the role of macroprudential policy in this risk environment.

The objective of macroprudential policy is to prevent and mitigate systemic risk by strengthening the resilience of the financial system and by smoothening the financial cycle.

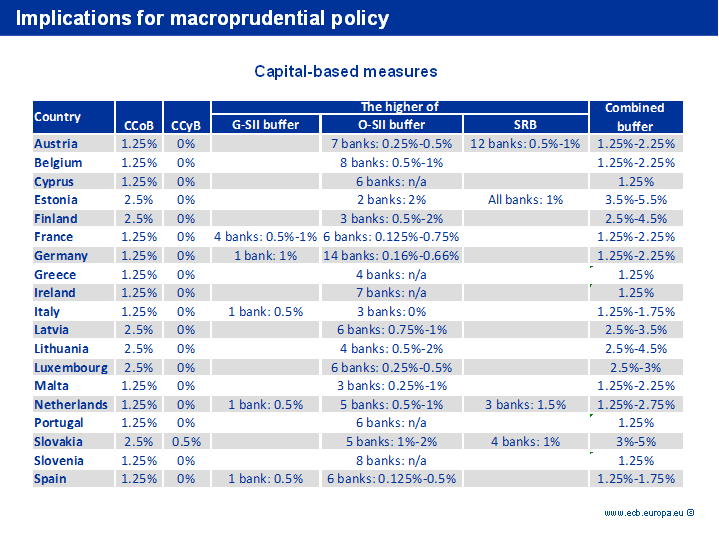

Figure 17

Since November 2014, when the ECB was granted macroprudential responsibilities and competence to top-up the measures taken by national authorities, more than 100 decisions on macroprudential measures have been taken (see Figure 17). As regards capital buffers to counter the “too-big-to-fail” problem, the decisions relate to eight globally important banks (in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain) and overall, 109 domestic systemically important financial institutions in all euro area countries.

Decisions also led to calibrations of the systemic risk buffer in four countries (Austria, Estonia, the Netherlands and Slovakia) and to the activation and the future increase of the countercyclical capital buffer to 1.25% in 2018 in Slovakia.[5]

Figure 18

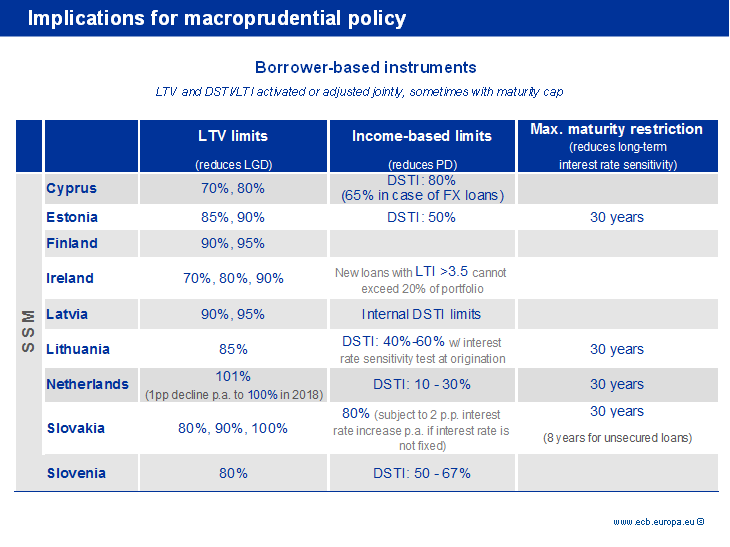

In addition, to address real estate risks, authorities raised risk weights for real estate exposure[6] and decided the use of Loan-To-Value (LTV) and Debt-To-Income (DTI) type of measures. Indeed, overall nine countries[7] have currently activated these borrower-type measures based on their national legislation (see Figure 18).

These measures influence the provision of credit and raise resilience by curtailing the tails of risk exposure. Given their effectiveness in curbing excessive credit flows, in December last year the ECB Governing Council called upon governments to implement the legislative basis for borrower-based measures in all euro area countries.

In addition, the ongoing review of the macroprudential framework in the EU provides an excellent opportunity to make these tools available to macroprudential authorities on a common legal basis. The review also needs to promote a clear allocation of tools between the macro- and micro-prudential supervisors to ensure a timely activation of the instruments. This implies that the macroprudential use of Pillar 2 should be abandoned and the procedures for Article 458 CRR should be strongly streamlined for an effective use of macroprudential policy.[8]

The capital- and borrower-based macroprudential instruments I just mentioned are targeting risks among the banking sector and the real economy. But given the structure of our financial system, they are not sufficient. In fact, a growing fraction of credit intermediation is conducted by non-bank financial institutions. Their risks are essentially related to maturity mismatch or leverage. However, the current European macroprudential toolkit grants regulatory authorities limited possibilities to act on these risks in the non-banking sector. Europe should thus expand the toolkit to cover these risk areas.

As regards liquidity mismatches, this year’s policy recommendations by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to address structural vulnerabilities from asset management activities[9] have been an important step in the right direction. The recommendations permit authorities to indicate adequate liquidity risk management tools in extraordinary circumstances to open-ended funds. This also includes the suspension of redemptions in times of stress.

The FSB policy recommendations also address issues of measurement and monitoring of leverage within investment funds, including data collection for calculating synthetic leverage. Both recommendations are important because of the links between leverage and liquidity risk. For instance, recent research based on European alternative investment funds has shown that leveraged funds experience greater investor outflows after bad performance than unleveraged funds.[10] By limiting leverage we would be able to reduce these propagation mechanisms in times of stress.

On the other hand, I see the application of further regulation to Securities Finance Transactions (SFT) as most pressing for macroprudential policy beyond banking. Authorities should be able to make macroprudential use of margins and haircuts in securities markets to control the build-up of excessive leverage.[11] Importantly, these tools reach beyond the banking system and can thereby address risks in the rapidly growing parts of the financial system. To safeguard financial stability in the euro area in the future, it is therefore essential that macroprudential authorities, particularly central banks, are provided by European legislators with an expanded toolkit.

Let me conclude.

Financial stability in the euro area has improved, accompanying the ongoing economic recovery. Compared to last year, the euro area financial system is more resilient today. Bank profitability has recovered somewhat and steps have been taken to address some of the structural challenges faced by the banking system, although clearly a lot more needs to be done. Monetary policy, even when recalibrated, will continue to keep a very accommodative stance in order to attain the price stability objective in a self-sustained way. This implies that, in the present configuration of risks, Europe and all other advanced economies will have to take macroprudential policy much more seriously or they will face the risk of other financial crises that monetary policy cannot prevent.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] Daly, K., (2016), “A Secular Increase in the Equity Risk Premium”, International Finance 19:2, pp. 179–200.

[2] Caballero, R. and A. Simsek, (2017), “A Risk-centric Model of Demand Recessions and Macroprudential Policy”, NBER Working Paper No. 23614.

[3] Bernanke, B., (2005), “The global savings glut and the US current account deficit”, Sandridge Lecture, Virginia Association of Economics, Richmond, Virginia, Federal Reserve Board.

[4] Caballero, R. and E. Farhi, (2014), “The safety trap”, NBER Working Paper No 19927.

[5] See “Macroprudential measures in countries subject to ECB Banking Supervision and notified to the ECB”, ECB.

[6] Belgium, Finland and Luxembourg.

[7] Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, The Netherlands, Slovenia and Slovakia.

[8] See “ECB contribution to the European Commission’s consultation on the review of the EU macroprudential policy framework”, ECB.

[9] See “Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Asset Management Activities”, FSB, 12 January 2017.

[10] See van der Veer, K., A. Levels, C. Lambert, L. Molestina Vivar, C. Weistroffer, R. Chaudron and R. de Sousa van Stralen, (2017), “Developing macroprudential policy for alternative investment funds, towards a framework for macroprudential leverage limits in Europe: an application for the Netherlands”; ECB and DNB Occasional Paper, forthcoming October 2017.

[11] See “Margins and haircuts as a macroprudential tool”, remarks by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at the ESRB international conference on the macroprudential use of margins and haircuts, Frankfurt am Main, 6 June 2016.

Europeiska centralbanken

Generaldirektorat Kommunikation och språktjänster

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Texten får återges om källan anges.

Kontakt för media