SME financing: a euro area perspective

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Conference on Small Business Financingjointly organised by the European Central Bank, Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, Centre for Economic Policy Research and Review of Finance, Frankfurt am Main, 13 December 2012

Ladies and Gentlemen, [1]

It is a pleasure to welcome you to the conference on “Small Business Financing” organised jointly by the European Central Bank, the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, the Centre for Economic Policy Research and the Review of Finance.

At the ECB, we regard small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as a crucial component of the euro area economy. Indeed, our deliberations on monetary policy systematically take into account the financial health of, and the growth prospects for, euro area SMEs. In particular, the financing environment and access to finance for euro area corporates are important elements in our policy-making process, both for standard and non-standard monetary policy decisions.

To illustrate the importance of small businesses in the euro area, consider the following facts: SMEs constitute about 99% of all euro area firms, they employ around three-quarters of euro area’s employees, and they generate around 60% of value added. At the same time, unlike large firms which are generally more profitable and have access to alternative sources of finance, such as bond or equity finance, SMEs are highly dependent on bank loans and credit lines. Due to asymmetric information and a higher risk of failure [2], SMEs tend to face higher costs for bank finance and higher rejection rates than larger firms. While finding customers – potentially due to weak aggregate demand – is usually cited as a bigger problem for SMEs than access to finance, it is still the case that they are particularly vulnerable to adverse real-financial feedback loops or supply disruption in the provision of bank credit.

Nevertheless, the years prior to the financial crisis were a period of smooth transmission of monetary policy, and there was little evidence that euro area SMEs were constrained over and above levels expected in the context of a sound financial system.

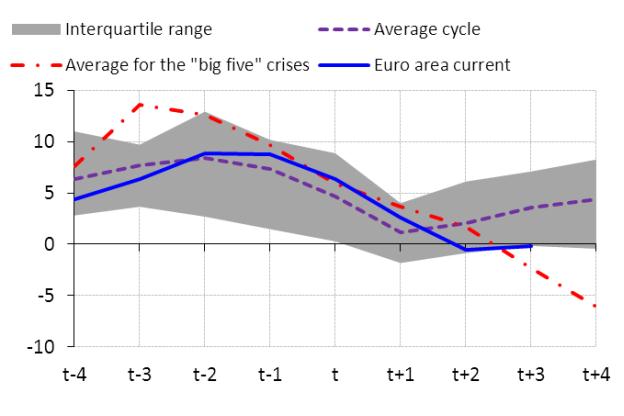

After mid-2007, however, the costs of finance started to rise and access to finance started to deteriorate relative to the pre-crisis period. In some euro area jurisdictions, the financial crisis first and the sovereign debt crisis later led to a reduction of the supply of credit to both households and corporates. In particular, rejection rates and rates on granted loans increased, and so did the share of firms citing access to finance as their dominant concern. On average, loans extended to non-financial corporations and households have declined more than during previous crises, mainly because bank funding shocks have been larger than in the past (Chart 1). The ECB has strived to alleviate funding stress by reducing policy rates, as well as by implementing non-standard monetary policy measures to provide liquidity to the banking system, where acute stress has occurred. This has also helped to mitigate the risks of disorderly bank deleveraging and to ensure adequate credit supply conditions in the euro area. Since 2010, the sovereign debt crisis has aggravated the funding conditions of euro area corporates and SMEs in particular, both by hurting their growth prospects and by forcing banks exposed to the sovereign debt of a number of euro area countries to rebalance their loan portfolios. By the same token, it is reasonable to argue that by counteracting undue risk premia on government bonds, the ECB’s non-standard measures, such as the OMTs, will contribute to restoring access to finance for the private sector.

Let me first talk about the financial situation of euro area SMEs. Before the crisis, survey evidence indicated that the main source of SME finance was retained earnings (around two-thirds). 10% was in the form of trade credit from suppliers or customers, and around 10% from external non-bank sources. About 15% of SMEs’ capital investment and operating expenses were financed with bank loans and credit lines. This average dependence on bank financing was as low as 8% in Portugal and as high as 22% in Ireland [3], indicating that small businesses relied substantially on the smooth functioning of the euro area’s banking sector.

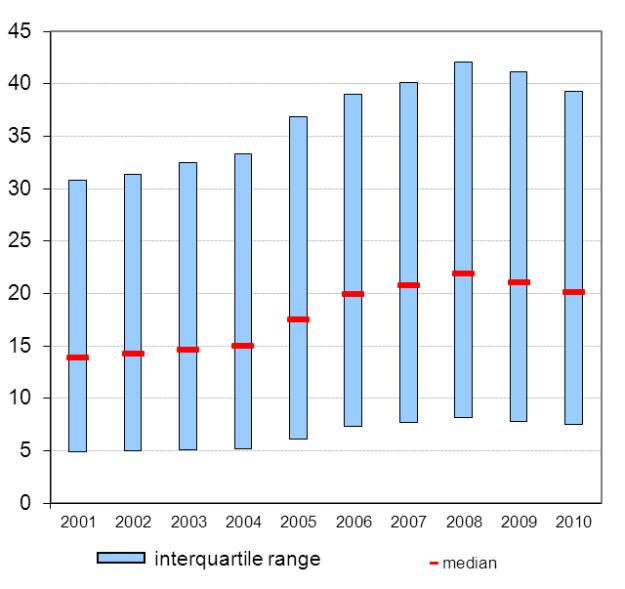

At the same time, there was a strong increase in credit growth in the euro area following a persistent easing of bank lending standards. According to the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey, euro area banks steadily relaxed their credit standards for loans or credit lines to enterprises during all but two quarters between Q2 2004 and Q3 2007. While the situation was broadly similar with respect to housing loans and consumer credit, which contributed to the build-up of housing bubbles in several euro area Member States, the corporate sector was still a substantial recipient of an overall euro area credit expansion. One of the adverse consequences of this credit expansion was that the euro area corporate sector had accumulated, on the eve of the global financial crisis, considerably higher leverage than during the early 2000s (Chart 2). This effect was largely driven by micro and small firms, for which financial leverage increased from 0.14 in 2004 to 0.19 in 2007. [4]

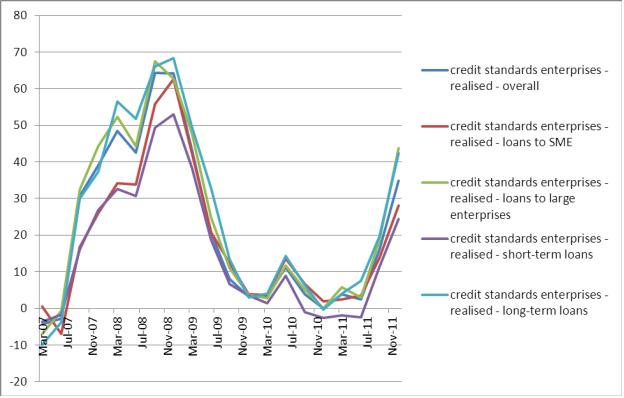

After August 2007, a sharp reversal of this process was observed. Credit standards on loans to enterprises tightened by on average 46% during each quarter between Q3 2007 and Q4 2008 (Chart 3). This process was accompanied by a rapid deleveraging by non-financial corporations. Nevertheless, as late into the financial crisis as the second half of 2009, the ECB’s Financial Stability Report singled out euro area SMEs as particularly vulnerable to further adverse credit market developments, on account of their low profitability and relatively high leverage levels.

The euro area sovereign debt crisis which started in the first half of 2010 and intensified in 2011 further contributed to the already restricted access to bank finance by the euro area corporates. While weakening demand resulting from deteriorating growth prospects in a number of euro area jurisdictions certainly played a role, tensions in sovereign markets affected the supply of bank credit as well. Because potential losses on sovereign debt securities have a direct negative effect on the asset side of the banks’ balance sheets and also affect their ability to pledge collateral to secure wholesale funding, the sovereign debt crisis effectively raised bank funding costs. To the degree that higher bank funding costs force banks to shrink and rebalance their loan portfolio, there should be a negative relationship between the riskiness of sovereign debt holdings and bank credit supply.

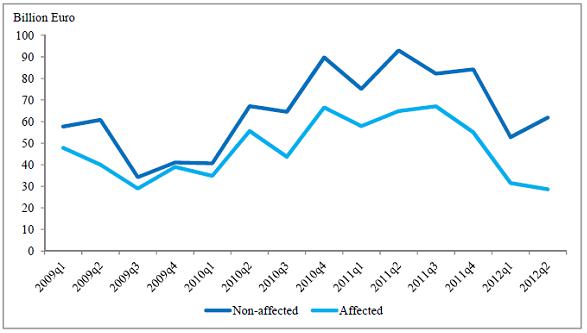

Recent evidence supports the view that the sovereign debt crisis has had a negative impact on the supply of bank credit. For example, since early 2010, banks exposed to foreign sovereign debt under stress have been lending substantially less on the syndicated loan market than otherwise similar banks with negligible exposure to foreign sovereign debt under stress (Chart 4). This overall reduction in lending is not driven by changes in borrowers’ demand and/or quality or by other types of concurrent balance sheet shocks. Part of the effect is due to the fact that investors update their views on the capacity of the domestic sovereign to support the banking system (the bailout channel). In addition to that, syndicated lending in the countries that have experienced the highest sovereign debt stress has been rebalanced away from domestic lending, reflecting deteriorating profit opportunities at home. This is markedly different from the ‘flight home’ effect observed during the 2008-09 financial crisis. [5]

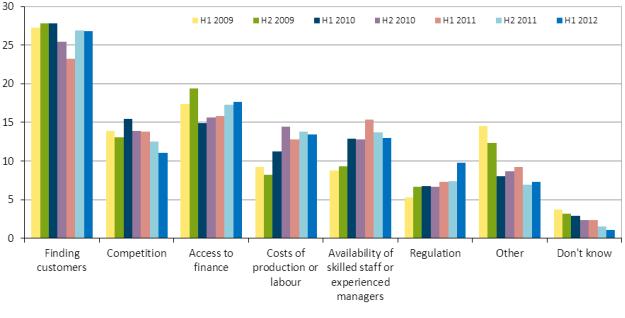

Syndicated lending, however, targets large non-financial corporations and so studies based on such data do not easily lend themselves to conclusions on the effects of the sovereign debt crisis on SME access to finance. Moreover, large public firms routinely substitute corporate debt for bank loans, especially during financial crises, [6] a shock-absorbing mechanism that is not available to SMEs. A simple comparison between very small loans (typically to SMEs) and very large loans (typically to large corporations) shows a substantial divergence across euro area jurisdictions which has worsened since the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis (Chart 5). More detailed information on SME access to finance can also be extracted from the ECB’s biannual survey on access to finance of SMEs in the euro area (SAFE). The survey suggests that the number of firms citing access to finance as the biggest problem they face has increased from less than 15% in the first half of 2010 to 18% in the first half of 2012 (Chart 6). At the same time, firms do not report an increase in financing needs (Chart 7), implying that loan supply factors dominate.

While this picture is purely descriptive, the SAFE also contains detailed firm-level information that allows us to calculate a component of credit constraints which is independent of agency problems. Preliminary analysis suggests that in 2010 and 2011, firms in countries whose sovereign debt was under stress faced on average a 20% higher probability of being credit constrained [7] than identical German SMEs. When decomposing the country-level effect into effects due to aggregate demand, credit risk, funding costs and the business cycle, the real interest rate that firms have to pay for credit stands out as the factor explaining the largest share of the cross-country variation in credit constraints. Such an analysis based on our survey on SME finance indeed suggests that for each 100 basis points by which lending rates decline, access to finance for euro area SMEs will improve by about 9%.

Emerging case studies also support the view that, by weighing on bank balance sheets, the sovereign debt crisis has led banks to tighten credit supply. For example, micro evidence from bank lending to SMEs in Italy suggests that since the start of tensions in sovereign debt markets, lending by banks exposed to sovereign debt has grown by 3 percentage points less than lending by unexposed banks, and that the interest rate they charge has been between 15 and 20 basis points higher. These effects are stronger for banks relying on domestic interbank funding. [8]

The Bank Lending Survey by the ECB is another source of information on realised bank lending standards to SMEs. According to the survey, after a period of rapid tightening, lending standards across the euro area had stabilised by the end of 2009 and the beginning of 2010. However, starting in the second quarter of 2010 credit standards started tightening again, and in December 2011 overall euro area lending standards to SMEs were twice as restrictive as two years earlier. This aggregate development hides important cross-country heterogeneity: for example, over the same period banks in Germany have actually loosened lending standards.

This combined evidence implies that, since the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis, credit supply in the euro area has become segmented. In most countries whose banking sectors are insulated from tensions in sovereign debt markets, access to bank credit has not decreased much and credit standards have not tightened more than what is typically observed during this phase of the business cycle. Conversely, in countries where the banking sector has experienced large balance sheet shocks related to deteriorating sovereign debt, access to bank credit has tightened substantially. Elevated premia in such market segments have in turn had repercussions on access to finance for corporates in general and for SMEs in particular. While growth prospects have deteriorated too, and consequently weak aggregate demand may be the dominant problem faced by euro area SMEs right now, impaired access to finance by the corporate sector in a number of euro area countries is clearly a problem that cannot be neglected and will come to the forefront when aggregate demand recovers.

Recognising that the sovereign debt crisis has impaired the smooth transmission of monetary policy, the ECB has responded vigorously. First, it has significantly eased the monetary policy stance. In July of this year, the ECB cut the main policy rate to 0.75%, the lowest in its history, and reduced the interest rate on its deposit facility to zero, in an attempt to reduce general market interest rates and to stimulate interbank lending. The ultimate aim of these actions is to restore the smooth provision of credit to euro area corporates and households.

In addition to that, the ECB has embarked on a number of non-standard measures: long-term liquidity provision up to three years, enlargement of the collateral set to be used in refinancing operations, direct intervention in the secondary market for government bonds with the SMP programme, and more recently the announcement of the OMTs. The objective of all these measures has been to help restore the transmission of monetary policy and address emerging heterogeneity by relaxing the balance sheet constraints of lenders (banks) and borrowers (firms and households). In this context, the Eurosystem has supported euro area SMEs both directly and indirectly, by allowing banks to pledge corporate loans as collateral with the Eurosystem. The goal is to ensure that firms, and especially SMEs, will receive credit as effectively as possible under the current circumstances. At present, the ECB holds on its balance sheet approximately €35 billion worth of ABSs with underlying SME assets, and approximately €60 billion worth of NFC credit claims.

Importantly, even though the policy rate is the same for all EA member states, non-standard monetary policy measures have benefited banks in jurisdictions which have been most severely hit by the crisis. In this sense, the non-standard measures of the ECB have addressed the different funding and stress conditions of the banking system in the euro area. Liquidity provisions, in particular, have helped banks to avoid disorderly deleveraging and have mitigated the decline of finance to the real economy. Research evidence suggests that liquidity policies, such as the fixed-rate full allotment (FRFA) and the longer-term refinancing operations (LTRO), have been associated with a significant economic effect, in that the level of industrial production is 2% higher and the unemployment rate 0.6% lower relative to a scenario with no such non-standard measures. [9] It also confirmed the view that, by providing ample liquidity through the FRFA and the LTROs, the ECB has been able, throughout the financial crisis, to reduce the costs arising to banks from restricted access to private liquidity funding and induce a softening of lending conditions, including to SMEs. This effect has been particularly strong in countries with weaker banking sectors. [10]

Reactions from the market so far imply that the ECB’s measures have contributed to alleviating stress in sovereign debt markets. The mere announcement of the OMTs, for example, has already helped to ease uncertainty in the system. The effect on confidence, a key factor for growth, has also been significant, and rightly so. Excessive government bond spreads have gone down, corporate bond and covered bond spreads have tightened. The latest Bank Lending Survey suggests that the announcement of the OMTs seems to have mitigated the adverse impact of sovereign risk on banks’ funding substantially by enabling a number of banks to regain market access, particularly in distressed countries. These developments are very important for the prospective financing of the real economy.

Let me conclude. Tensions in euro area sovereign markets brought the financial system under stress at a time when it was stabilising in the wake of the global financial crisis. Both market and survey indicators suggest that these tensions have resulted in a deterioration of bank lending, in particular to small businesses. Unconventional monetary policy measures have so far contributed to mitigating funding stresses in the banking system and disordered deleverage. In turn, this has allowed firms and households to maintain access to finance. But the non-standard measures have also helped to remove uncertainty and restore confidence. The ECB will continue to pay particular attention to the situation of euro area SMEs when implementing its non-standard measures. Nevertheless, all actions from central banks, although crucial for alleviating frictions and dysfunctionalities in financial intermediation and the transmission mechanism, and also for guaranteeing financial stability and the sheer survival of the system, cannot replace reforms in individual euro area countries aimed at reducing fiscal and external imbalances and creating an innovative and competitive economic environment. Only such reforms can foster sustainable growth and employment in the future.

Thank you.

Chart 1. Real loan growth, current crisis vs. previous crises

Source: DG-E/MP/CMT internal calculations.

Note: ‘“Big five” crises’ refers to the financial crises in Spain (1977), Norway (1987), Finland (1991), Sweden (1991), and Japan (1992), where the starting year is in parenthesis.

Chart 2. Leverage of euro area NFCs

Sources: Bureau van Dijk AMADEUS database and DG-E/MP/CMT calculations.

Chart 3. Bank lending standards in the euro area

Source: ECB’s Bank Lending Survey.

Chart 4. Impact of stressed foreign sovereign debt exposure on bank syndicated lending

Source: Popov and Van Horen, 2012.

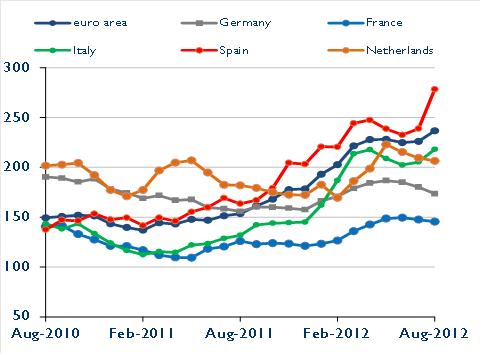

Chart 5. Spread between lending rates on very small and large loans

Source: ECB and MIR database. Very small loans are loans of up to €0.25 million, large loans are those above €1 million.

Chart 6. The most pressing problem faced by euro area SMEs ( percentage of respondents)

Source: SAFE.

Chart 7. Change in external financing needs of euro area SMEs over the preceding six months

Source: SAFE.

-

[1]I wish to thank Alex Popov for his contribution to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

-

[2]Small firms as a rule do not enter into publicly visible contracts with employees, suppliers, or customers, do not issue securities that are continuously priced in public markets, and do not have audited financial statements. In addition, about a quarter of new small businesses disappear within two years, and more than half disappear within four years. See: Berger, A., and G. Udell, 2012. The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance 22, 613-673.

-

[3]See the 2004 Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey by the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

-

[4]Financial leverage is defined as the ratio of the sum of debt securities and bank loans to total assets.

-

[5]Popov, A., and van Horen, N., 2012. The impact of sovereign debt exposure on bank lending: Evidence from the European debt crisis. ECB mimeo.

-

[6]For evidence from the U.S., see Ivashina, V., and B. Becker, 2011, Cyclicality of credit supply: Firm level evidence, Harvard Business School Working paper 10-107. For evidence from the euro area, see De Fiore, F., and H. Uhlig, 2011, Bank finance versus bond finance, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 43, 1399-1421.

-

[7]A credit-constrained firm is a firm which a) is rejected when applying for a loan, b) receives less than 75% of the desired loan amount, or c) is discouraged from applying because it believes its loan application will be rejected.

-

[8]Bofondi, M., Carpinelli, L., and E. Sette, 2012. Credit supply during a sovereign crisis. Bank of Italy mimeo.

-

[9]Gianone, D., Lenza, M., Pill, H., and L. Reichlin, 2012. The ECB and the interbank market. Economic Journal 122, F467-F486.

-

[10]Ciccarelli, M., Maddaloni, A., and J.-L. Peydró, 2012. Heterogeneous transmission mechanism: Monetary policy and financial fragility in the euro area. Economic Policy forthcoming.

Europeiska centralbanken

Generaldirektorat Kommunikation och språktjänster

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Texten får återges om källan anges.

Kontakt för media