Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa: Economist, policy-maker, citizen in search of European unity

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, European University Institute, Fiesole, 28 January 2011,

It is an honour for me to deliver this speech today in honour and memory of Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa. This speech has been prepared by a group of colleagues who immediately volunteered to contribute as soon as they learned that I had been invited to give such a speech. [1] They were colleagues of Tommaso during his time at the ECB and I am very pleased to be their porte-parole today.

Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa had a very rich and complex personality, which I can’t sum up in a few minutes or a few paragraphs. So I’ll talk about him as an economist, a policy-maker and a citizen. The leitmotif in all these areas of Tommaso’s life was a Kantian quest for European unity, a mission to which he dedicated his professional and private life.

The Economist

If there is one trait that stands out throughout Tommaso’s career, spans all his activities and engagements, all his speeches and books, it is the energy and determination with which he pursued his convictions and causes. Once Tommaso started ‘owning’ a new idea, he would relentlessly seek out all its implications and communicate it to all possible fora and audiences until the impossible became possible, and the inconceivable started making sense. He always did so with rigour, but also with a very personal flair; some called it the ‘TPS style’.

Tommaso defined himself as a “practitioner”, a policy-maker, but his action was always deeply and unambiguously grounded in economic thought. At the same time, he shared Keynes’ view that practical men are often slaves of some defunct economist. Even in his early years as an economist, he identified those risks of enslavement and then sought to free himself from them by way of his life-long policy engagement: the dichotomy between general economic equilibrium theory and monetary theory; the dichotomy between Nationalökonomie and international economy; and the dichotomy between economic theory and institutions. [2] He always aspired to bring these dichotomies to an end, by properly integrating the monetary, international and institutional dimensions into his assessment of economic policy.

I specifically wish to mention two ideas here, two strands of economic literature: the theory of optimum currency areas and the impossible trinity proposition. But he was no slave to them; rather, he mastered and reinterpreted them, and turned them into food for thought.

Mundell’s theory of optimum currency areas offered a critique of the overlap between “money” and “state”, a link which, in the early 1960s was still considered as immutable and irreversible. While a similar critique had led to Friedrich Hayek’s idea of the privatisation of money, supra-nationalisation was Mundell’s response. Tommaso’s great insight was that this second avenue would make it possible to improve the Treaty of Rome and to move beyond it, thus setting the conceptual foundations for the Treaty of Maastricht. Monetary Union was not seen, however, as an end in itself, but rather as a dynamic process that would prove sustainable only if policy behaviours and economic configurations in Europe remained consistent with the prescriptions contained in the theory of optimum currency areas. I will come back to this issue when discussing Tommaso’s legacy.

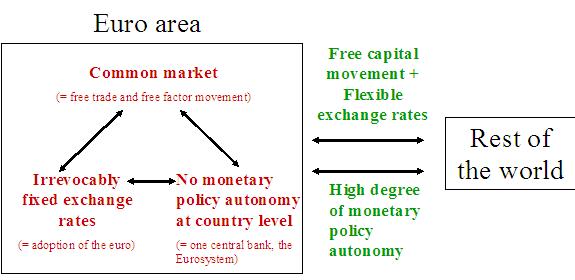

The impossible trinity proposition, a corollary of the Mundell-Fleming model, stated that a group of countries cannot simultaneously keep a fixed exchange rate, pursue autonomous monetary policies, and maintain full capital mobility: in pursuing any two of these goals, the third one must be necessarily given up. This raised a major intellectual and policy challenge for European countries trying to strengthen economic cooperation after the Second World War: it seemed simply inconceivable to jettison any of the three goals.

Tommaso realised that financial repression would have provided only a temporary response to this question. The accomplishment, in the early 1990s, of the central goal set down in the Treaty of Rome – a European common market, implying free trade and free capital movement – called for enhanced, and eventually fixed, exchange rate stability across member countries. This is because exchange rate volatility, coupled with systematic devaluation of a group of currencies against other currencies, would have eventually impaired the very functioning of the common market, a theme to which I will return later. Indeed, the whole history of European monetary cooperation between the collapse of Bretton Woods and the early 1990s is marked by attempts to maintain fixed exchange rates. These attempts were periodically punctuated by major tensions between national currencies (with consequent clashes between Member States) each time a country was forced (or tempted) to devalue or even abandon the common fixed exchange rate arrangement. In this context, the economically most coherent way to reconcile intra-regional free trade and free capital movement with fixed exchange rates would have been for European countries to adopt a single monetary policy and therefore a single currency floating against the rest of the world. This was, in Tommaso’s view, the right approach to the solution of the impossible trinity once the objective of the Single Market had been attained (Figure 1). And indeed Tommaso preferred to talk about an “inconsistent quartet” ( quartetto inconciliabile), which included a fourth element, free trade, in order to take full account of the European context. In the early 1980s these ideas were still pioneering and visionary, but we all know how influential they have become in shaping the history of our continent, to the extent that they have transformed themselves from vision into reality.

Figure 1 – Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa’s view of the impossible trinity proposition

While Tommaso saw a role for exchange rate adjustments at global level, he was very well aware that, to avoid imbalances accumulating and crises – even systemic crises – breaking out, sovereign countries have to pay proper attention to the negative externalities of their domestic policies and to enhance their cooperation, also as members of stronger international institutions and fora. Growing economic and financial interdependence led, in his view, to the identification of public goods not only at country or regional level but also at world level. A couple of examples would be global financial stability or a multilateral trade system. As I will further elaborate below, he was no fan of benign neglect and of leaving exchange rates solely in the hands of the market. Once again, we can see today how compatible his view of the world is with the current international situation.

Tommaso’s call for greater cooperation and supranationality in certain areas of policy- making was fascinatingly complemented by his full belief in the principle of subsidiarity, also enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty, according to which each policy should be conducted by the lowest and least centralised competent authority possible. From this perspective, the ideas of cooperation and supranationality were understood as economic necessities, not as abstract political stereotypes.

Not long ago Tommaso became actively involved in an initiative of the Triffin International Foundation, which is based in Louvain-la-Neuve. Last February he delivered a speech entitled ‘The Ghost of Bancor’. Bancor was a far more ominous presence than Il Commendatore Don Pedro who drags Don Giovanni to hell in Mozart’s opera of the same name. His aim in that speech was to revisit the arguments proposed by J.M. Keynes in 1943 for a new international monetary system and eventually a world currency called Bancor. Tommaso argued that the ‘Triffin dilemma’ is still unresolved: if the main international standard and reserve currency is a national currency there is an insurmountable inconsistency between domestic needs (in the short term), and global policy needs (in the long term). This inconsistency had led, over time, to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was not resolved either under the US dollar-based non-system that took its place: a market-led system without a clear anchor. Over the last 10-15 years this has been referred to as Bretton Woods II. However, Tommaso noted that “exchange rates were determined by a bizarre combination of market behaviour and of policy actions vis-à-vis the dollar. Floating European currencies, including the euro, were at the mercy of the waves of a market prone to prolonged misalignments. Asian currencies were largely sheltered from the vagaries of the market and subjected to intense management by the national authorities”. Thus, the illusion of flexible exchange rates was exposed yet again: incidentally, this is another long-lasting preoccupation of Tommaso (like the “impossible trinity” I mentioned previously).

Now, coming closer to our current situation and challenges, Tommaso noted that, while a consensus has emerged about some of the main factors at the roots of the present crisis – such as the growing and persistent current account imbalances, inadequacies in financial regulations and supervision, the systemic risk generated by excessive leverage combined with risky financial products, and so on –, there’s a lack of recognition about the fundamental flaws in the present monetary (non-) arrangements. He quoted Herbert Stein: “ That which is unsustainable comes to an end”. Tommaso also warned that “ when an unsustainable process ‘comes to an end’, variations in prices and quantities are of a magnitude and drama incomparably greater than one sees in the healthy conduct of economic life on a daily basis”. The ‘end’, the breaking point, often occurs at an unexpected moment and in an unexpected way. It’s a concept that is reminiscent of the Minsky moment.

“It is easy to argue today that if the monetary regime had sounded the alarm bell and triggered an adjustment in time, the crisis would have been either averted or, at the very least, mitigated.” Instead, “monetary oversight headquarters' alarm systems and internal adjustment mechanisms were switched off”. To their credit, “the G7 and the international institutions kept pointing out year after year that the imbalances were unsustainable. Yet they could do nothing to correct them or to prevent the crisis because they had neither the tools nor the authority to force the use of domestic measures to address the problem”. Moreover, “there is no way to get round the requirement of a policy framework anchoring the global standard to an objective of global stability”. [3]

Thus, the ghost of Bancor “has returned to claim his due”. At the least, we need a common exchange rate mechanism “in which every country, bar none, agrees to shoulder its responsibility and to enter into a commitment with the other countries regarding its currency's external value; and in which the exchange rate is determined by the interaction between the market and economic policy”. This would provide the foundations for a genuine international monetary order.

But it will not be easy to achieve this goal, warned Tommaso, as “the elements that are helping to keep this disorder alive are robust political and economic interests but also, and above all, the prevailing practical and intellectual inertia. The thoughts that I have expounded to you here tonight are an invitation to overcome that inertia.”

The Policy-maker

Tommaso joined the Banca d’Italia in 1968. This was not an obvious decision for someone with his background: an affluent and cultivated family from the north of Italy. This choice clearly reflected a wish to serve his country rather than pursue personal enrichment. The Banca d’Italia, with its tradition of technical expertise and high standards of public service, was the obvious place to go. Yet in that choice there was not only a drive to do something but also an urge to understand. That same urge led him to give all those who attended the conference held to mark his leaving the European Central Bank a small bookmark with a drawing by Goya of an old man with the motto “Aun aprendo”, or “still learning”.

The need to combine doing and understanding was strong for a young economist working in the research department of the Banca d’Italia at the end of the 1960s. The Bretton Woods system, which had given Italy a solid monetary framework, was starting to show the signs of wear, while the growth miracle of the Italian economy was approaching its limits. The country clearly had problems reacting to the changing times with an appropriate economic policy: the budgetary policy started to show the lack of control that would beset it for decades afterwards. Monetary policy, which was about to lose its exchange rate anchoring to the dollar, had difficulties finding an alternative anchor. Tommaso saw in the efforts to establish a European monetary order not only a chance to make decisive progress towards the objective of a unified Europe but also an opportunity to help Italy get out of its difficulties in managing the economy in a sound and stability-oriented manner. Hence his support for Italy’s membership of the European Monetary System (EMS), even against those who argued, with some reason, that Italy would have difficulty in complying with the exchange rate constraints of the EMS. He was, of course, aware of this, yet he did not want such an endeavour to start without Italian participation. Moreover, he believed that the so-called “monetarist” view – according to which taking decisions on the exchange rate, and a fortiori moving towards a common currency would have effects on the conduct of monetary policy and on the economy – reflected the reality better than the so-called “economist” view, according to which exchange rate constraints and, again a fortiori, a common currency can only be the climax of a perfect convergence of monetary policy and economic conditions.

These same ideas informed his action when he served at the European Commission from 1979 to 1983, the early years of the European Monetary System. There again he was confronted with an apparent trade-off between national and European forces and between monetary stability and a European monetary project. All his efforts, again as an economist and as a policy-maker, were devoted to solving these tensions and taking them in a single direction – towards a European monetary endeavour that would bring monetary stability.

Tommaso followed the same course when he returned to the Banca d’Italia in 1984, even if he had then to deal more directly with the continuing difficulty of Italian governance to deliver sound and stability-oriented macro policies, notwithstanding the efforts of the Banca d’Italia, where he was a member of the Board.

While actively aiming to bring monetary stability to Italy and to move towards monetary unification in Europe, Tommaso started working in payment systems – an apparently obscure area of work. Before he took on responsibilities in this area at the Banca d’Italia, payment systems were not considered an independent (and even less core) function of central banks. The activities carried out by payment system departments today largely did not exist at that time and to some extent were done by IT departments and back offices.

Tommaso provided the conceptual and economic rationale for a greater involvement by central banks in this area. A smooth functioning of payment systems is essential to ensure that money performs one of its key functions, being a ‘means of exchange’. Ensuring an adequate means of exchange (i.e. confidence in the currency and its adequate and effective circulation) is one reason why central banks were originally established. Central bank money is indeed universally recognised as the safest mean of exchange and therefore as the ultimate means to discharge financial obligations. Smooth functioning of payment systems is also crucial for the effective conduct of monetary policy and financial stability

Between 1985 and 1991, Tommaso promoted and developed in Italy all the components of an efficient and sound payment system. The action plans were described in two publications issued by the Banca d’Italia. Led by Tommaso, the Banca d'Italia played a central role as an operator of settlement facilities, regulator and catalyst.

As an operator, the Banca d'Italia launched the Italian RTGS system (Birel) for interbank money market uncollateralised transactions and the settlement system for Italian government bonds. As a catalyst, the Banca d'Italia ensured cooperation within the banking industry that led to the creation of the other necessary infrastructure for large-value, retail and securities transactions. As a regulator, the Bank created the conditions for ‘oversight’ of the infrastructure. And indeed Tommaso was the first person to use the word ‘oversight’ to describe the function to be conducted for payment systems, as opposed to ‘(banking) supervision’.

These activities were launched by Tommaso before the Banca d'Italia was assigned formal specific statutory competence in this field. “ The function begets the organ and leads to the establishment of the legal basis” as he used to say. With hindsight, it’s evident that what Tommaso did in Italy laid the foundations for the development of an analogous process at European level.

His view was that each integrated currency area should have its own ‘domestic’ infrastructure. Tommaso introduced a definition of ‘domestic’ that went beyond national borders and covered the whole euro area.

As at the Banca d’Italia, almost everything Tommaso did at the European Central Bank in the field of payment systems was innovative. Indeed he developed a paradigm of model for the operational features that each integrated monetary area should have, and continuously and consistently pursued their implementation.

Tommaso once again had a chance to be involved more actively in policy-making at European level when he acted as secretary for the Delors Committee when it prepared the blueprint for the single currency in 1987-89. Tommaso was not a member of the Committee and, as such, he was not supposed to intervene during the meetings, but his personal relations with Jacques Delors and with Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, then Governor of the Banca d’Italia and a member of the Committee, as well as his role as ‘rapporteur’ allowed him to greatly influence the deliberations. That was an excellent opportunity to combine his two aspirations: a stable currency but also one that would powerfully contribute to European Union.

In the 1989-91 negotiations that led to the Maastricht Treaty, Tommaso fought hard to maintain the momentum towards monetary union which had been established by the Delors Committee. Indeed, he feared that the decision to establish a temporary institution, the European Monetary Institute, instead of the European Central Bank, would be a critical mistake, also considering that in the meantime in a number of countries, again including Italy, policies were not sufficiently stability-oriented.

We know the story since then: the project of monetary unification came close to failure with the repeated exchange rate crises in the first half of the 1990s. But Europe’s efforts in its historical endeavour eventually succeeded. In the 1993-97 preparatory work for the launch of the euro, Tommaso had yet another chance to show his unique ability to build on the one hand, a strong conceptual, analytical and policy framework (the ‘vision’) and, on the other hand, to implement a concrete set of measures and actions to turn the vision into reality.

In the area of financial stability, Tommaso elaborated and worked towards the realisation of three fundamental ideas.

First, he provided a far-sighted yet, in the end, realistic contribution to the design of the architecture for financial supervision in Europe. He was convinced that in a single market, and even more so within a single currency area, the supervisory framework had to be as convergent as possible, entailing a transfer of supervisory responsibilities from national to EU level. Indeed, he was convinced that the public good of financial stability also needed to be provided at EU level, and that would have necessitated the creation of an EU supervisory framework. At Maastricht, the Member States could not agree on this. Tommaso considered this a mistake – and the EU had to learn its lesson from this omission the hard way, during the financial crisis.

Tommaso regarded the convergence of supervisory rules and of supervisory practices through enhanced cross-border cooperation as intermediate steps towards the final objective. Notably, he was the first person to coin the term ‘EU supervisory rulebook ’ and, moreover, he was the founder of FESCO, the forum for supervisory cooperation in the securities field. In his view, cross-border supervisory cooperation should be so strong and effective that the collective behaviour of supervisors would appear as a single one. All these ideas started to take shape with the establishment of the Lamfalussy Committees (CEBS, CESR and CEIOPS), whose main purpose was to enhance supervisory convergence and cooperation. But his ideas have only been fully realised recently, with the setting-up of three new European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) as part of the European System of Financial Supervision. The ESAs have the main task of pursuing the EU supervisory rulebook and strong coordination powers over national supervisors.

The second fundamental idea Tommaso worked on was to define the role of central banks in financial stability. He saw this role as being clearly distinct from the one that central banks may have in prudential supervision since it entails monitoring, controlling and managing the risks to the financial system as a whole (what is now commonly referred to as systemic risk) instead of managing the risks incurred by individual financial institutions, a task performed by supervisors. In attempting to design a fully fledged framework for this function, he recognised the need to identify specific policy instruments which could address systemic risk, including the interplay with the instruments used for monetary policy purposes. In doing so, he essentially anticipated the issues which eventually came to the fore in the wide policy debate stemming from the financial crisis under the heading of macro-prudential supervision. This debate eventually led to the establishment in Europe of the European Systemic Risk Board. He contributed to the development of the financial stability function at the European Central Bank, mainly by pushing for the publication of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review, which provides a euro area-wide perspective of risks to financial stability.

His third fundamental idea was to defend, constantly, the role of central banks in prudential supervision. While he recognised that it was probably impossible to define an optimal model for the organisation of financial supervision, he firmly believed in the synergy between the central banking and supervisory functions, and supported a close relationship between the two. He expressed this position in all discussions on reforms of supervisory structures at national level. It is telling that one of the main lessons of the financial crisis is that, where a clear separation between central bank and supervisory functions exists, the trend is to shift the responsibility for prudential supervision to the central bank.

In the area of international relations, Tommaso was convinced that, as the central bank of an economy roughly the same size as that of the United States, the Eurosystem had to gradually develop its international role and policy: it owed this to its ‘domestic constituency’ as well as to the global community, in which monetary unification in Europe could play an important role by enhancing global policy cooperation. In this area too, Tommaso was a fervent advocate of the national central banks of the euro pooling their forces, acting as a system and playing a role consistent with the institutional mission and interests of the Eurosystem. His belief in international cooperation was founded on the conviction that there are, on the global agenda, many economic issues – including trade, finance, global imbalances, energy and the emergence of new global and regional players. Their scale and complexity call for policy efforts that go beyond national borders and make cooperation at global level desirable and feasible. In a series of lectures he gave here at the European University Institute shortly before the end of his term at the European Central Bank, he argued that the long-term solution, what he had earlier called the ‘royal way’, would be to adapt institutions to today’s policy needs, to reform them with a view to enhancing their effectiveness and representation, extending in many cases some of their operational and decision-making practices. Tommaso belongs to that group of personalities who played a decisive role in shaping international cooperation. He contributed to formal and informal group discussions at global level, but also worked on a bilateral basis with countries, institutions, and people from Africa, Asia, Latin America and from the Mediterranean countries.

One of his initiatives was to set up the high-level Eurosystem Seminars, regularly bringing together the members of the Governing Council with governors from selected central banks, for example, those from EU candidate countries, or from countries around the Mediterranean, or from countries in Africa or the Middle East that were considering a monetary union for their own region, or even from Latin American countries. It was something unique to have – regularly sitting around the same table – the Governor of the Central Bank of Israel and the Governor of the Palestinian Monetary Authority sharing views, in an open and candid manner, on the challenges that they were facing, together with their European counterparts.

Tommaso’s intellectual curiosity was not constrained by borders, on the contrary. He constantly wanted to grasp the essence of what was at stake for central banks worldwide and to share his vision of a ‘textbook central bank’, while at the same time taking into account the particular circumstances and institutional structures of a given central bank.

The Citizen

As I said in my introduction, Tommaso was more than an economist and a policy-maker. He had a sense of history, a determination to bring the civilization of Europe to a higher level. He was proud of Europe but also recognised its fragility, and was acutely aware of the continent’s rivalries, divisions and conflicts over the centuries.

The relationships between the nations of Europe changed immensely during the almost 40 years of Tommaso’s career as a central banker. He was a central banker by profession, and an advocate of a united Europe by conviction. As a child he had seen cities bombed and soldiers marching through the streets outside his house. As a teenager he listened to his history teacher explaining that the day before (25 March 1957) an important treaty had been signed in Rome. Six European countries had just committed themselves to establishing the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital. To achieve this goal they were prepared to renounce part of their sovereignty. The project was economic in content and political in nature. A united Europe then became the strongest of Tommaso’s personal convictions.

Tommaso was convinced that, after the four freedoms were established, after common economic legislation was adopted, after the Single Market and a single institution to enforce common competition rules were set up, the next step was a monetary union. He saw the creation of the euro as a key integrative step in the field of monetary policy and was very aware of the ECB’s responsibility to make it a success and a stepping stone for further integration. But monetary union, he realised, was a project fraught not only with political difficulties but also with deep conceptual problems. The economist and the policy- maker in him helped the citizen to find and contribute solutions to these conceptual problems.

In the second half of the 20th century, the debate over monetary policy resulted in a consensus: the central bank must be both independent and accountable. An important part of Tommaso’s work, before and at the European Central Bank, was to help establish both independence and accountability as part of a central bank’s profile. The two form a critical pair, he thought, with the latter naturally complementing the former.

The independence of the Eurosystem is a means to an end. It is instrumental in achieving the objective of price stability assigned to the central bank of the euro by the Treaty, which has deliberately established both the primacy of price stability and the principle of independence of the central bank. Independence would be much harder to justify if monetary policy had been given the responsibility to bring two objectives into balance, say price stability and high employment. So, independence is essential if the Eurosystem is to carry out its mission successfully. It protects the Eurosystem from short-term political considerations. But it does not mean the absence of democratic control. In a democracy, independence and accountability are two sides of the same coin.

Accountability means that the central bank is subject to the scrutiny of the elected representatives of the people. In Tommaso’s analysis this is an essential part of our political order. The European Central Bank has been assigned a specific mission and given the independence to effectively pursue it, so the ECB has to be held accountable for fulfilling it. The ECB must explain and justify its decisions. It is accountable to the people of Europe. In the political order of the EU this means being accountable to the European Parliament, the only body that derives its legitimacy directly from the people.

The ideas Tommaso developed as economist emerged powerfully in his function as a leading thinker at the ECB. Deeply convinced that, especially in all European matters, “ Nothing is possible without humans, but nothing is lasting without institutions” (as Jean Monnet said), his concern was to shape the ECB as an independent institution that is nevertheless – and necessarily – embedded within the overall institutional context of the EU. This shaping was a dynamic process, because the EU as a ‘polity in the making’ is constantly evolving. He also devoted particular attention to making the ECB’s actions and policies understandable for the people of Europe, to whom the ECB is ultimately accountable.

When Monetary Union was established he pushed for a ‘customer-friendly’ name to embrace what he called ’the central bank of the euro’ as well as the ECB and the national central banks of the euro area. The Treaty was difficult to read, even for lawyers: so the first Bulletin of the ECB introduced the term ‘Eurosystem’, which has been used since by the national central banks implementing monetary policy. Today the word ‘Eurosystem’ is well known and is included in the Lisbon Treaty.

When the opportunity came to change the Treaty to make it closer to the citizens, it was proposed to make the ECB one of the EU institutions, recognising its role in the further integration of Europe. Traditional central bankers were sceptical, fearing that a closer link to the other, more ‘political’ Union institutions would undermine the independence of the European Central Bank. Tommaso was at the centre of this debate; he managed to strike a balance between, on the one hand, maintaining and even reinforcing the European Central Bank’s independence and keeping its special features and, on the other hand, reinforcing the role that the ECB, as a newly recognised institution, more visible to the people, could play jointly with the other institutions to foster European unification. Notably, the Lisbon Treaty explicitly mentions the financial independence of the ECB and that it has a legal personality separate from that of the EU.

A key concern in the early years of the European Central Bank was to implement the concept of central bank independence in a concrete and practical manner, also in interactions with the political authorities of the Union, whether the Council of Ministers or the European Parliament. There were, after all, very different national traditions concerning central bank independence – in some countries, the notion of an independent central bank was a more recent phenomenon, not fully anchored in the day-to-day political reflexes and actions of national authorities. While being a staunch defender of the European Central Bank’s independence whenever necessary, Tommaso never viewed the emergence of an effective economic decision-making structure at European level with trepidation, as a potential threat to the ECB’s independence. On the contrary: he thought it indeed desirable from the central bank’s perspective, and that of the people of Europe – that “ independence should not mean institutional loneliness”.

Tommaso’s legacy

Jean Giono, the Frenchman who turned pacifist after experiencing the horrors of the First World War, wrote once that in order to appreciate the exceptional qualities of human beings we must observe how they behave over a long period of time. We certainly did that with Tommaso for many years before his untimely departure. But, I would add, we should also consider the influence he will continue to exert. This is something that today, with the memory of his dramatic last moments still fresh, we can only venture to guess. Only the passing of time and reflections on his actions and writings can give shape and measure to his legacy as an economic thinker, a policy-maker and institution-builder, and above all else, as an inspiring leader for future generations.

On the subject of leadership, the first point I would like to make is his commitment to and almost boundless passion for work. For Tommaso, no draft was ever perfect, no project ever completed, no idea ever worked out in a full and satisfactory manner. The limits to work were set by deadlines, not by exhaustion or satisfaction or even less by personal need. Then came the motivation, the purpose of working. He used to say that people must decide early on if they want “ to earn, to learn or to serve”; in other words, if their goal in life is material reward in business, intellectual pleasure in academic research and teaching, or the moral satisfaction of serving the collective good as a civil servant. As I said earlier, when opting to work for the Banca d’Italia, he undoubtedly chose to serve. The two other options were for him, at most, occasional and ancillary complements. And there is no doubt that he demanded the same commitment from his collaborators.

Yet, above all, the legacy that Tommaso leaves to those who observed and helped him over the years concerns how he dealt with issues. The first step was always to define a problem, to find the right combination of words to convey its meaning and content. Defining as a means of understanding and communication; a perfect example is the speech he gave in 2000 entitled ‘An institutional glossary of the Eurosystem’. This spoken ‘glossary’ came in eight parts, with headings such as mission, independence and accountability, and each part started with a definition and continued with a rigorous dissection and analysis, always conducted in a positive frame of mind. Amid the disorder of conflicting and discouraging elements there was always a constructive way out; the problem was to find it. And in order to find it – this was a cornerstone of Tommaso’s intellectual approach – one should not have prior judgement guiding thoughts and actions, but rather have firm beliefs on the ultimate aims.

Tommaso had also a clear working method, which influenced many of us, especially at the start of our professional lives. Setting precise deadlines, what economists call ‘time T’, getting a good understanding of what has to be done by that time, for example, writing a document, a speech, a regulation, and producing something which would be clearly understood even by somebody unfamiliar with the topic. Ideas are influential if they arrive in time and can be easily understood. “ Form matters as much as substance” he used to say.

To give you a better idea of his working methods, let me add here a personal memory. In the second half of 1990 Italy held the Presidency of the Council of the European Communities (as it was then). A key task of the special Council summit in October of that year was to finalise the preparation of the intergovernmental conference on Economic and Monetary Union. A lot of preparatory work had been done since the Delors Committee by various groupings. A political decision was now needed. By holding the Presidency Italy would have a key role in influencing the outcome of the Council meeting.

In the spring – several months before the start of the Presidency – Tommaso managed to convince the Italian Prime Minister to set up a group of four sherpas, with representatives from the President’s office, the Finance Ministry, the Foreign Ministry and the Banca d’Italia. I accompanied Tommaso on several of these occasions. A few preliminary meetings were held before the summer but were largely inconclusive. Most participants considered that the October summit was too far away and that there were too many imponderables to start meaningful preparatory work. In their view they needed ‘political guidance’.

Back at the bank after one of these meetings, Tommaso, visibly irritated by the lack of progress, asked me to come into his office. When we got there he told me that we had to start the preparatory work for the European Council ourselves – “ Nobody else will do it.” I had no clue what the work would involve. But in his view it was quite simple. The main outcome of the European Council was a statement mandating the intergovernmental conference to change the Treaty to allow for monetary union, the so-called Council Conclusions. We had to write a first draft of these Council Conclusions, even if the meeting was four months away. “ Three pages, no more!” he told us. In terms of content, it was vital to specify a starting date for the transition to monetary union (1994), and to make a reference to the final stage and to the single currency. [4] That would be the starting point for the discussions and negotiations with the other governments. “ The one who holds the pen – he used to say – has the most influence”. And so I went back to my office and started writing the three pages, which after numerous iterations, amendments, insertions and deletions resulting from the negotiation process, evolved into the final October 1990 European Council Conclusions, including the long negotiated footnote reporting the fact that one country could not agree with the Conclusions. Back home, Mrs Thatcher was unable to convince her critics that such a footnote was a defeat, a failure to stop monetary union.

I would like to close with what can be considered the five strong elements of Tommaso’s legacy as an economist and policy-maker.

The first and most obvious is his faith in Europe. I don’t need to add much more on this. Europe as a continent of peace, a ‘gentle’ force helping to find the roots that unite us and a way to overcome problems that, approached nationally, might retrigger the divisions and horrors of the past. Europe was always the focus, even when – in Tommaso’s sometimes unexpressed opinion – its representatives or actions did not deserve it. Tommaso’s Europe was an aspiration and an ideal, much bigger and longer lasting than the individuals that may at any given time symbolise it.

The second element is that the future development of the Union can and will probably be built on the ‘solidarité de fait’ created by economic interdependence. Tommaso was fond of reminding us that it was a single article in the US constitution – the one regulating inter-state commerce – that was used to lay the foundation of a significant role for the federal government in US economic policies. In very much the same way, the necessities of managing interdependence will – and indeed do – lead to embryonic joint economic management: the EFSF/EFSM/ESM has put €500 billion at the disposal of the Monetary Union’s ‘federal’ level to manage the sovereign liquidity crisis. Who would have thought this possible one year ago? The same is true for the European System of Financial Supervision. And for a reinforced economic governance framework with a stronger role for EU institutions and processes. But solidarity must go hand-in-hand with responsibility, and the common European destiny requires a reinforcement and a clarification of the common rules of the game. Tommaso was right: the asymmetry between a single monetary policy and national economic policies must be transitory. Now we need to make another step forward towards European integration.

The third element or guiding compass in his approach to European and other issues was his faith in institutions. Let’s adopt his method and look at the definition first: “ structure or mechanism of social order and cooperation governing the behaviour of a set of individuals within a given human community”, reads the Stanford Encyclopedia, which continues: “ Institutions are identified with a social purpose and permanence, transcending individual human lives and intentions, and with the making and enforcing of rules governing cooperative human behaviour”. Only institutions (whether simple gatherings or fora, or formal debating and decision-making groups, up to structured organisations with physical premises) give continuity and strength to human efforts and aspirations that are, by nature, transient and mortal. “ Nothing is possible without humans, nothing is lasting without institutions”, Jean Monnet wrote. It mattered little to Tommaso that institutions could experience periods – perhaps long ones – of inconclusiveness and idleness. Their existence itself had value, as the premise and promise of future progress.

The fourth key element is, I think, his approach to economics. There is no doubt that Tommaso was an economist of the highest order: his early studies at MIT with Franco Modigliani, his outstanding scholarly publications, his constant use of sophisticated economic thinking bear witness to this. But there is likewise no doubt that Tommaso was a particular economist, unique in his own way. Economics was not for him – as for many in the profession today – an intellectual exercise in which implications are drawn from axioms through deductive logic. It was a method to analyse problems and to devise solutions that should constantly be tested in real life and discarded, if necessary, in a Popperian sequence. Economics should adapt to circumstances – not the other way round.

His clashes with doctrinaire economists (often classical, but not only) are proverbial. Time prevents me from telling you more, but there’s one that should be mentioned here because it turned out to be central to his career, namely his views on the role of exchange rates as an instrument for adjusting economic imbalances. The doctrine, for which several Nobel prizes have been awarded, is that exchange rates are, in a wide variety of circumstances, an easier and less painful way to correct accumulated disequilibria among countries than changes (notably, reductions) in nominal wages and prices at national level. Not for Tommaso. As I said, he viewed exchange rate variability, with the possibility of competitive devaluations and currency wars that it entails, as a fundamentally uncooperative and undesirable way to settle economic divergences. Hence his preference for monetary cooperation and ultimately monetary union, in Europe and elsewhere. Cooperation, to be effectively durable, was to be supported by institutions, notably central banks.

This brings me to the fifth and last cornerstone of Tommaso’s thinking and practice, his conceptions of central banking and his actions as a central banker. This is the area to which he devoted most of his professional life. He did not start his career as a central banker – he often joked, particularly with those he considered not concrete enough, about his early job as a clothes seller – but in the end he incarnated the quintessential and all-round central banker as nobody else did, though always in an original way. He viewed central banks as complex and multifaceted financial institutions pursuing the public good along several interconnected paths. It is the polar opposite of the notion, prevailing in the years prior to the current crisis, of a single-minded and ring-fenced authority regulating interest rates just to achieve stable prices. Price stability is key, but should be filtered through a broader notion of monetary, financial and economic performance. And it should never be attained – typical of modern macroeconomic models – by simplistic decision rules, by some kind of autopilot. The strategy and transmission of monetary policy cannot abstract itself from the interconnections between the financial system as a whole, from the money markets where short-term assets are bought and sold, or from the payment system, the technology through which money is exchanged for goods and services.

Tommaso was bothered by the simple-mindedness and lack of solidity in the analytical fads and fashions of modern macroeconomists, whose published models tag money to the rest of the economy in an artificial way as an afterthought. To understand money, he felt, one must explore the functions it provides as a means of payment, a measure of value, and a store of value. He was impatient with conceptions that considered only part of this tripartite structure or disregarded the interconnections. This is at the heart of his long-standing interest in financial stability and the working of payment systems, areas he considered inextricably linked to monetary policy. It seemed, at times, as if he was looking for a deep understanding of money in the links between the three functions, for something like a unifying theory for all three. But such theories are hard to devise, as physicists know only too well. I’m not sure if, in the end, Tommaso felt he had solved the puzzle, or at least broadened his understanding of it. What I am sure is that it is precisely in the areas of financial stability and payments that he provided some of his most outstanding and lasting insights.

Conclusions

This review of Tommaso’s life and legacy is obviously partial, with a focus on his central bank experience, in particular at the ECB. But his contribution is much broader. He certainly believed in exchanging ideas. I heard him say once, during his short tenure at the Finance Ministry, “ If people are willing to discuss issues in a rational way and in good faith, I am confident a solution can be found”. I am not sure it really applied to the specific issue we were talking about at that time, but it certainly applies to the way Europe has been constructed since the start, including over the last few months. It reflects his vision of, and hopes for, Europe in the 21st century.

It is a distinct trait of human nature to become pessimistic as we grow older, to think that the worst is to come when faced with unexpected events, to distrust the younger generation, to foresee the risk of war and terrible events. Tommaso was not like this. He profoundly trusted human beings and invested heavily in younger collaborators because he firmly believed that only by getting the people of Europe closer together there will be a better world.

This is the inspiration we need.

-

[1]Francesco Papadia coordinated the preparation of the speech with contributions by Ignazio Angeloni, Ettore Dorrucci, Mauro Grande, Gabriel Glöckler, Francesco Mongelli, Francesco Papadia, Pierre Petit, Massimo Rostagno, Daniela Russo, Pierre van der Haegen, Chiara Zilioli

-

[2]See “Moneta, Commercio, Istituzioni: Esperienza e Prospettive della Costruzione Europea” - Lectio Doctoralis di Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa per il conferimento della Laurea Honoris Causa in Economia Internazionale del Commercio e dei Mercati Valutari (Trieste, 19 November 1999).

-

[3]From The Ghost of Bancor: the Economic Crisis and Global Monetary Disorder, speech given by Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, Louvain-la-Neuve, 25 February 2010. See http://www.uclouvain.be/cps/ucl/doc/triffin/documents/TPS_EN_finale_clean.pdf

-

[4]Bini Smaghi, L., Padoa-Schioppa, T. and F. Papadia, “The Transition to EMU in the Maastricht Treaty”, Essays in International Finance, Princeton, No 194, November 1994.

Europeiska centralbanken

Generaldirektorat Kommunikation och språktjänster

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Texten får återges om källan anges.

Kontakt för media