Heterogeneity and the ECB’s monetary policy

Speech by Benoît Cœuré at the Banque de France Symposium & 34th SUERF Colloquium on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the euro on “The Euro Area: Staying the Course through Uncertainties”, Paris, 29 March 2019

From the beginning of the euro area’s existence, it was well known that it did not meet all of the classic requirements of an optimal currency area. Some critics have seen heterogeneity across Member States as the factor that would ultimately cause the collapse of the single currency.

But the euro is still here, despite years of crisis. While managing heterogeneity between regions and countries has been a challenge – at times tremendously so – this challenge is not insurmountable. No single currency area in the world is free of heterogeneity, including the ones widely regarded as most homogeneous.

In my remarks this morning, I will argue that the ECB has always found ways to accommodate heterogeneity, particularly at times when it threatened to impair the uniform transmission of monetary policy.

But I will also argue that if we want to minimise episodes of demoralising output and employment losses, as we experienced after the financial and euro area crises, and if we want to avoid overburdening monetary policy, then policymakers need to act more forcefully to reduce the major sources of euro area heterogeneity – that is, we need a better economic policy framework.

Pre-crisis view on heterogeneity

To structure my remarks, I would like to briefly recall the pre-crisis view on heterogeneity in the euro area.

Inflation differentials between regions and countries were not only thought to be unavoidable, they were in fact thought to be a desirable feature of a currency union.[1] The idea was that the structural transformations sparked by monetary integration and the single market, together with the free movement of goods, capital, services and labour, would create the conditions for all countries to thrive and exploit their comparative advantages.

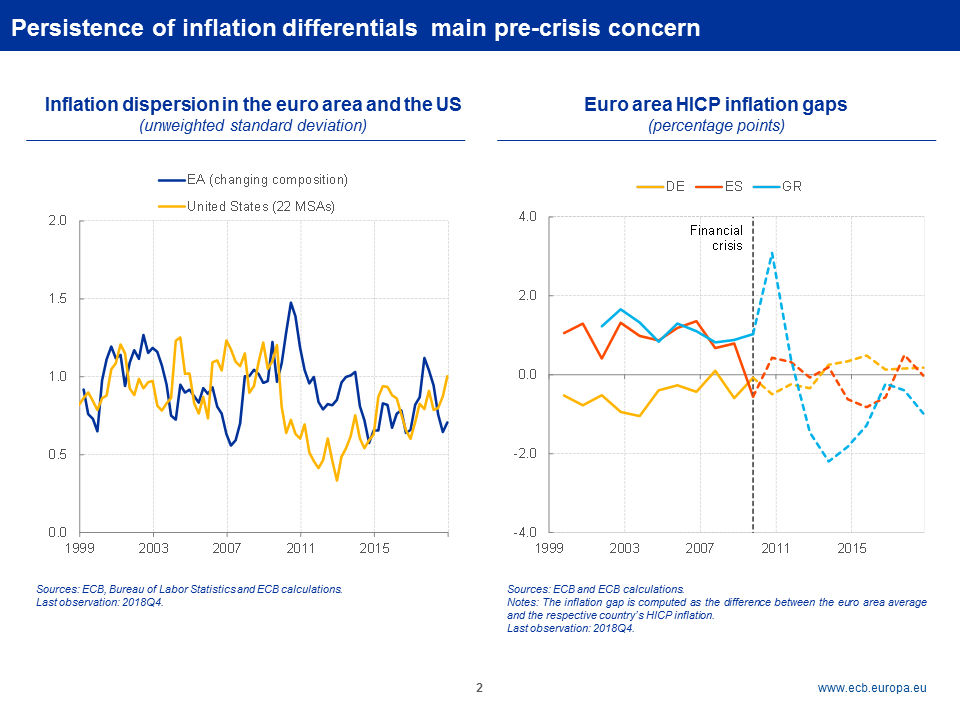

The prime concern at the time was that if these inflation differentials persisted, they could undermine price competitiveness and thus hold back growth. This view was corroborated by the fact that inflation dispersion among euro area countries was not very different from the level observed between US metropolitan areas, but it was much more persistent. You can see both aspects on my first slide.

The idea that heterogeneity could impair monetary policy transmission and jeopardise the stability of the euro area was a distant thought, for three main reasons.

First, cross-border financial integration was on the rise and was increasingly seen as an effective shield against idiosyncratic shocks. A broad operational framework for monetary policy that took into account the heterogeneity of both the ECB’s counterparties and available collateral would complement growing market-based defences.[2]

Second, the euro area was built on the idea – or, one might say the hope – of monetary dominance, with policymakers in all other domains supporting the ECB’s area-wide mandate by addressing nominal and real rigidities and by running prudent fiscal policies which could be used in rainy days. Such support was a necessary complement to a single monetary policy which would be overburdened if it were held accountable for national developments.

And, third, the pre-crisis view was inspired by growing evidence that inflation expectations across the euro area had largely decoupled from actual national inflation outcomes and had converged towards the ECB’s definition of price stability.[3]

In other words, the combination of balanced fiscal policies over the cycle, the ECB’s track record and a clear primary mandate provided for a stable nominal anchor for the euro area as a whole. This served to coordinate the largely decentralised decisions of price and wage-setters within and between heterogeneous economies.

The need to enhance private risk-sharing in the euro area

This pre-crisis view was not wrong. But it underestimated the shortcomings in the euro area’s institutional framework and its potential to unleash diverging forces.

Let me take each aspect in turn, starting with financial integration.

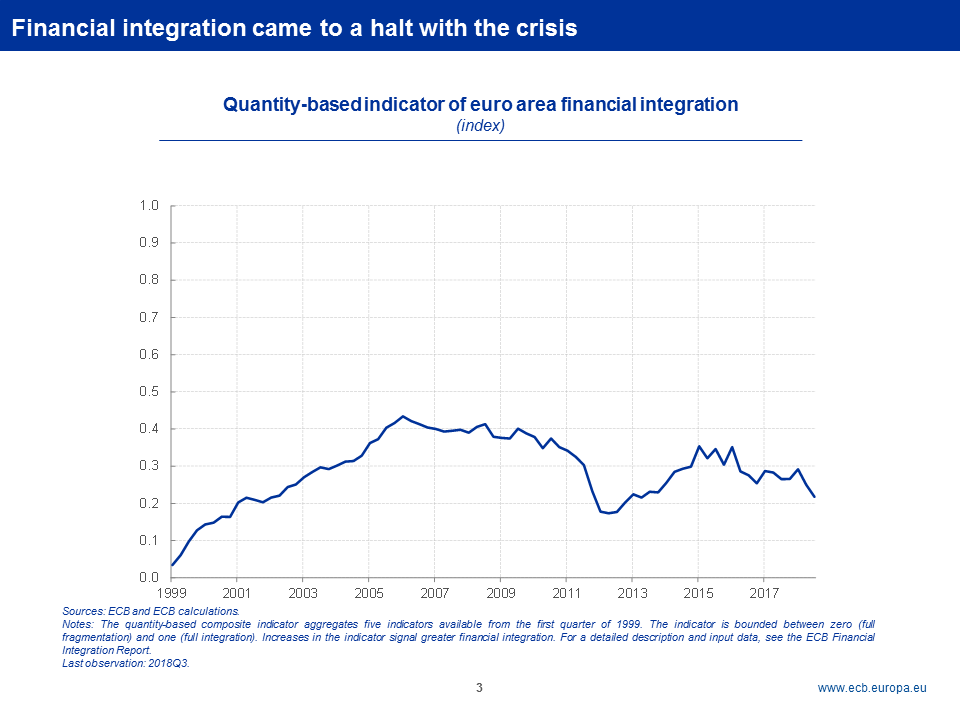

European capital markets indeed appeared to be becoming more integrated, and hence provided for increased cross-border risk-sharing, before 2008. You can see this clearly on my next slide, which shows a composite indicator of euro area financial integration produced by the ECB. But since the crisis broke, integration has reversed. It currently stands at 0.2 on a scale where zero represents full fragmentation.

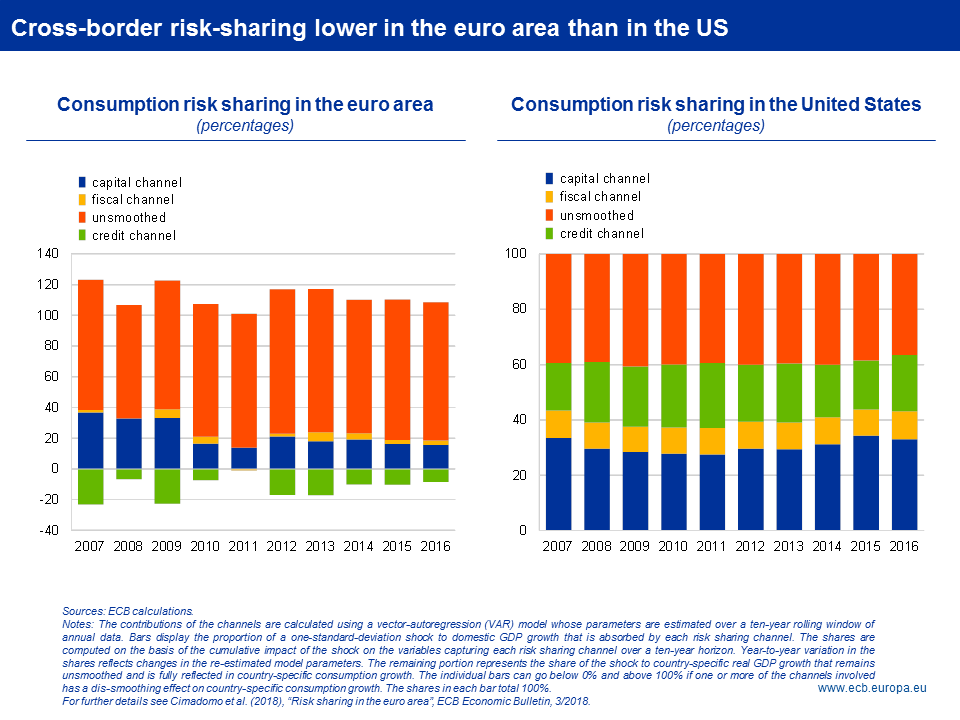

As a result, cross-border risk-sharing in the euro area is almost non-existent. On my next slide you can see that, currently, around 80% of a country-specific output shock remains unsmoothed, while in the United States it is at most 40% for a state-specific shock.[4]

More worryingly, the negative green bars point to a dangerous procyclical credit channel in the euro area. That is, households and firms borrow abroad in good times and pay back in bad times.[5]

These aspects were often overlooked before the crisis. Financial frictions, for example, were largely absent from mainstream central bank models.[6] Generally speaking, there was a lack of attention to “financial plumbing” – to the fact that differences in liquidity, capital and supervisory standards meant that banks’ reaction to shocks could magnify heterogeneity.[7]

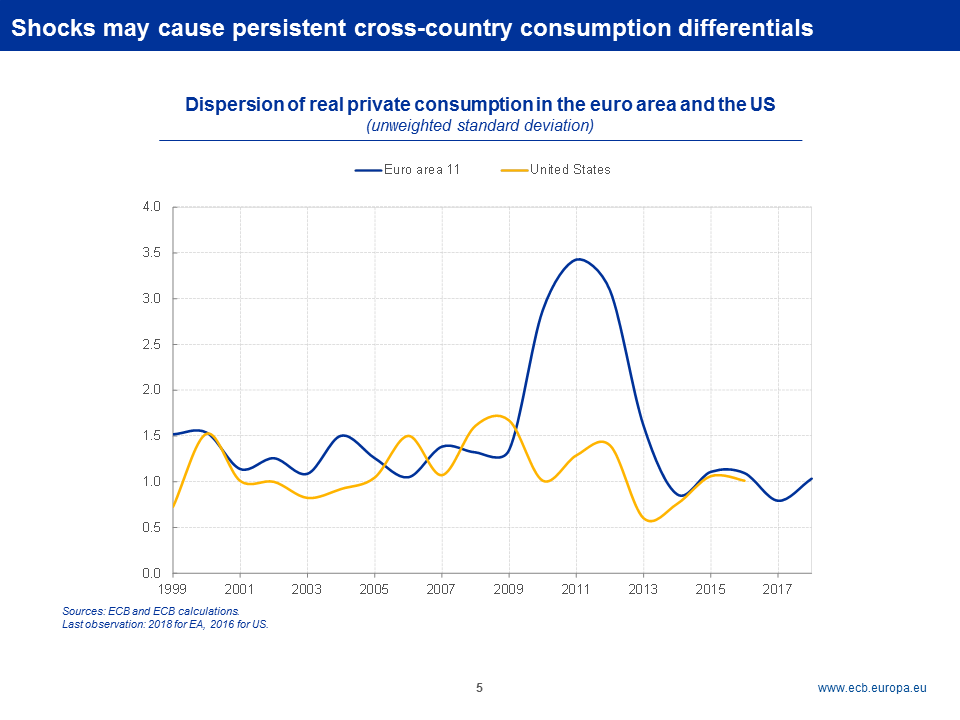

The creation of the banking union has fixed many of these shortcomings, but not all of them. In particular, without further private risk-sharing, idiosyncratic shocks will continue to cause persistent dispersion in economic outcomes. You can see this clearly on my next slide.

Dispersion in real per capita private consumption across euro area countries was twice its historical levels for a period of more than three years after the outbreak of the global financial crisis. By the same standard, the effects of recession and financial crisis are hardly visible for the United States.

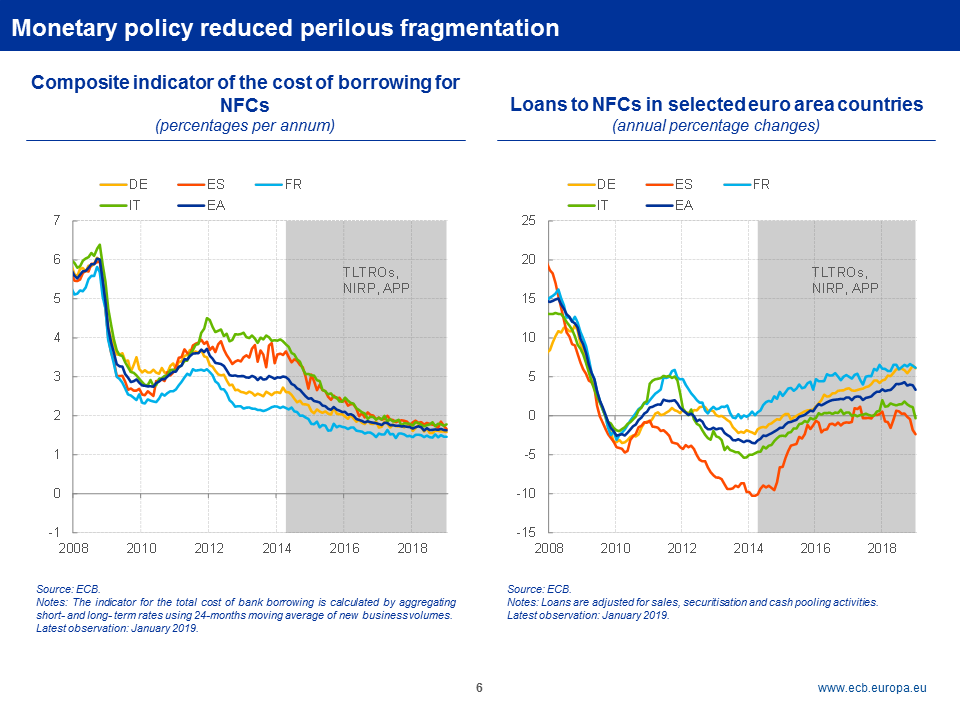

Monetary policy cannot eliminate such persistent differences, but it can accommodate them. We have proven that a carefully calibrated package of non-standard policy measures, including our targeted long-term refinancing operations, asset purchases, forward guidance and negative rates, can successfully overcome even significant causes of heterogeneity, such as the impairment of the bank lending channel across large parts of the single currency area in the wake of the euro area’s sovereign debt crisis. You can see this on my next slide.

Today, the bank lending channel in the euro area is fully operational after years of fragmentation. To protect this achievement, we decided at our last monetary policy meeting in March to launch a new series of targeted long-term refinancing operations, “TLTRO-III”, starting in September 2019.

But to address the underlying vulnerabilities, and to bolster the credit and capital channels of risk-sharing, we urgently need to make progress in completing the banking union and kick-starting the capital markets union. Financial markets that can absorb shocks efficiently reduce the need for macroeconomic stabilisation and thereby free up costly political capital.

Structural policies to enhance resilience and feed convergence

The second aspect of pre-crisis thinking concerned the role other policy domains should play in supporting the single monetary policy. I will focus here on the structural side and turn to fiscal policy in a minute.

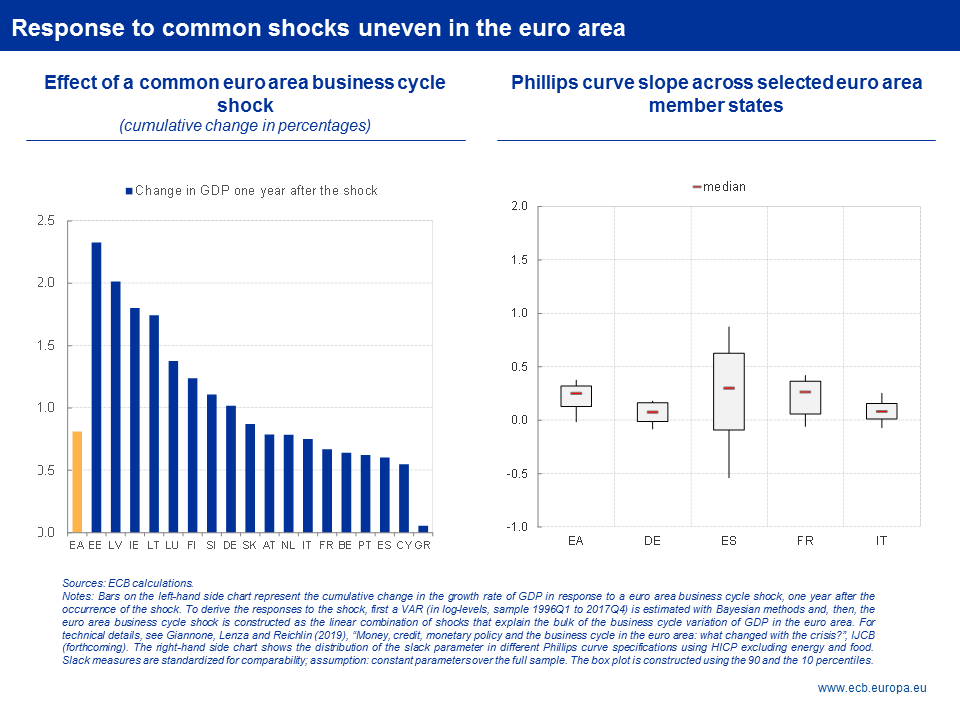

Although pre-crisis policy advice strongly focused on reducing nominal and real rigidities in product and labour markets, today there are still significant differences across countries in the response to common euro area-wide shocks.

My next slide shows two ways of looking at this.

On the left-hand side you can see ECB research on the extent to which output in each country responds to a common area-wide shock. Clearly, there are significant differences, even among countries of broadly comparable size.

On the right-hand side you can see Eurosystem estimates of the slope of the Phillips curve.[8] It shows a high degree of heterogeneity across euro area countries for the sensitivity of core inflation to economic slack. In other words, country-specific factors of inflation remain considerable, for example the degree of wage negotiation centralisation. These factors are also related to national institutions.

The upshot is that, in this environment, monetary policy is more difficult to calibrate. Different transmission mechanisms propagate the same shock to different degrees and with lags that may vary across countries.

Minimising these differences in transmission does not require all countries to adopt the same economic structures.[9] What matters is for countries to have institutions that deliver the right outcomes, both individually and jointly. Our system of economic coordination, the European Semester, still falls short of achieving this objective.[10] And as a consequence, it still falls short of supporting adequately the single monetary policy.

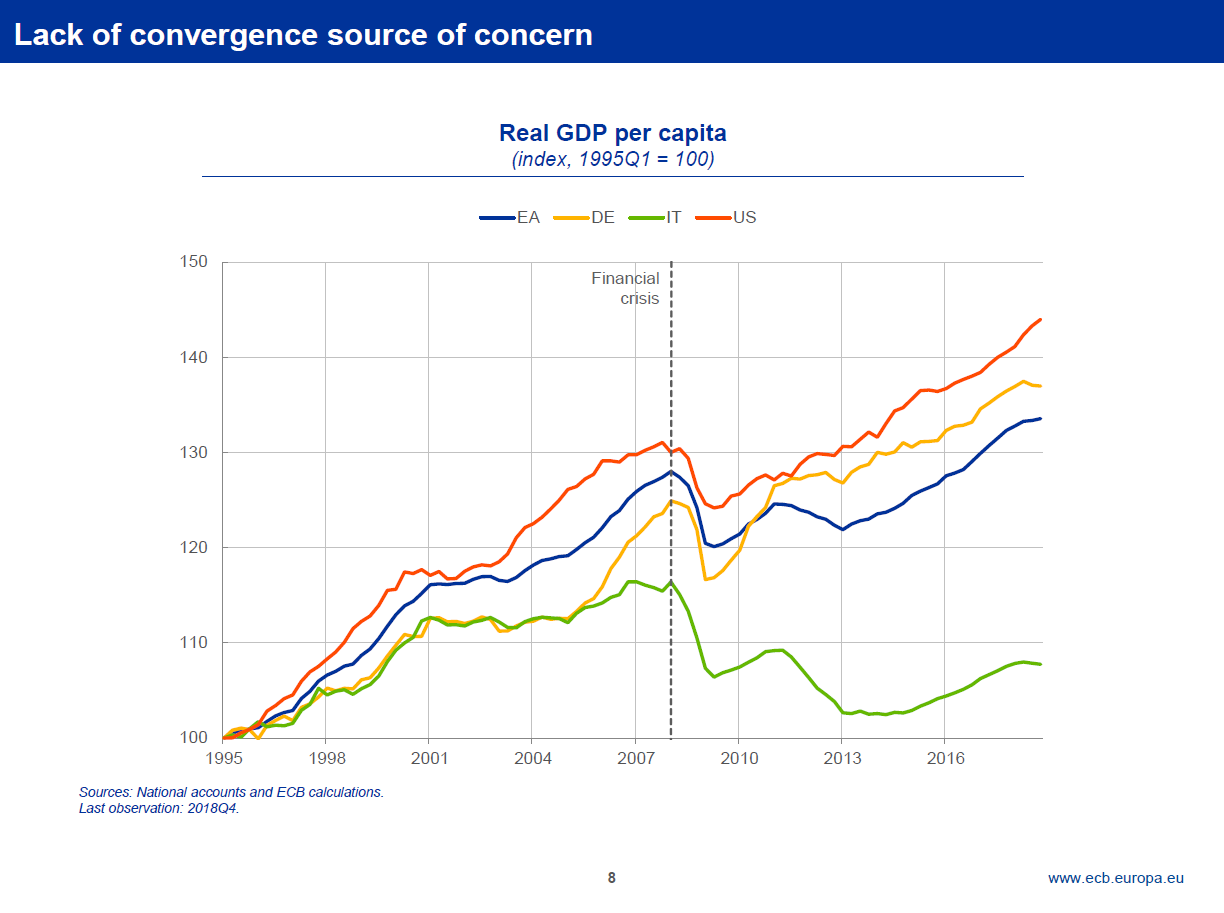

Strengthening domestic institutions is not only about improving shock absorption capabilities. It is also about cohesion and sowing the seeds for renewed convergence. You can see this on my next slide.

The more benign pre-crisis view of heterogeneity reflected the fact that the direction of travel was at least similar among euro area countries, and not too different from, say, the United States. As you can see from the chart, the longer we wait to improve the quality of the institutions that underpin domestic growth and living standards, the larger the gap will be that separates the best from the rest.

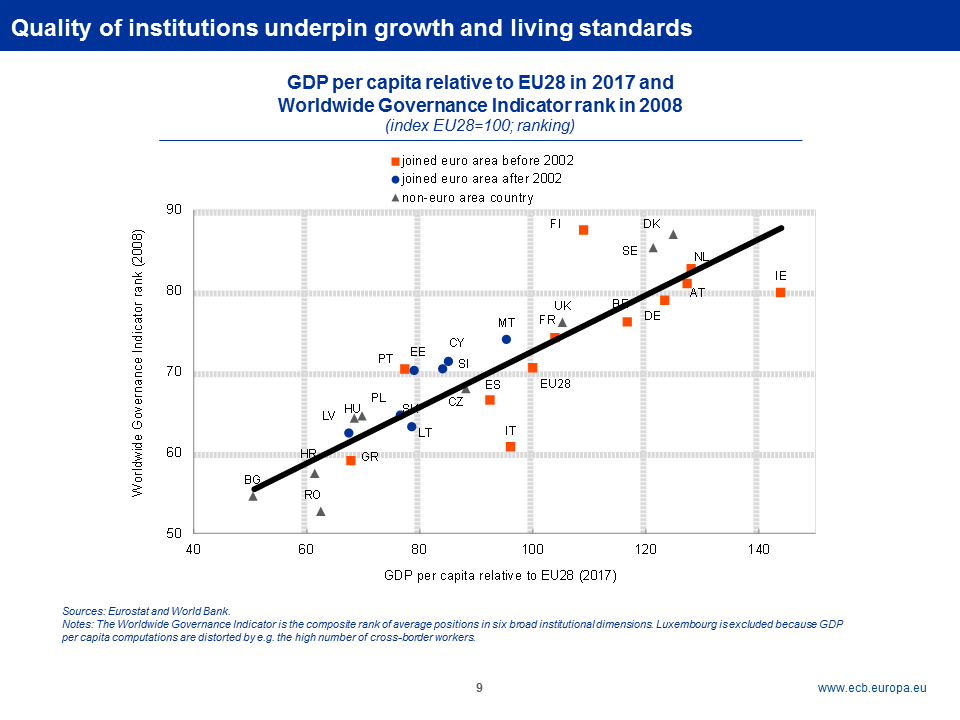

My next slide emphasises the close empirical relationship between the quality of national institutions and living standards. This is primarily a national responsibility, meaning that in order to recreate convergence the heavy lifting has to be done by reforms in individual Member States. That said, the recently proposed budgetary instrument for competitiveness and convergence in the euro area is a useful and necessary complement.

Strengthening policy complementarities

The third and last pre-crisis aspect concerned the role of monetary policy in coordinating price adjustments in a heterogeneous currency union. The ECB’s definition of price stability had become a strong area-wide nominal anchor that largely marginalised the effects of actual inflation outcomes on expected future inflation, thereby cushioning cross-country heterogeneity.

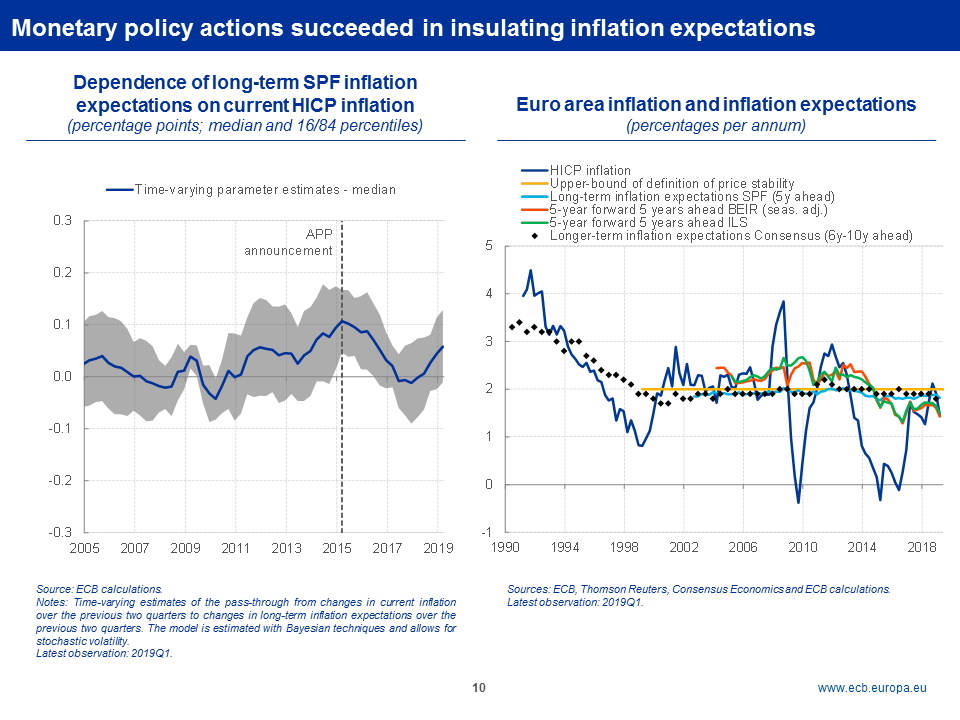

You can see this on my next slide. Before the crisis, survey-based long-term inflation expectations revealed no statistically significant response to changes in actual HICP inflation. They were well anchored at levels below but close to 2%. You can see this on the right-hand side.

But the persistence of the effects of the crisis has, at times, challenged the coordinating role of monetary policy. We have faced instances where protracted softness in actual inflation has contributed to a reappraisal of medium to long-term inflation expectations. You can see this in the grey range moving away from the zero line on the left-hand chart between 2010 and 2015.

Forceful monetary policy action has succeeded in restoring the important role that stable inflation expectations play for the inflation process in a heterogeneous currency union. The chart clearly demonstrates that the announcement of the asset purchase programme in January 2015 helped to avert the danger of current inflation dragging down expected inflation.

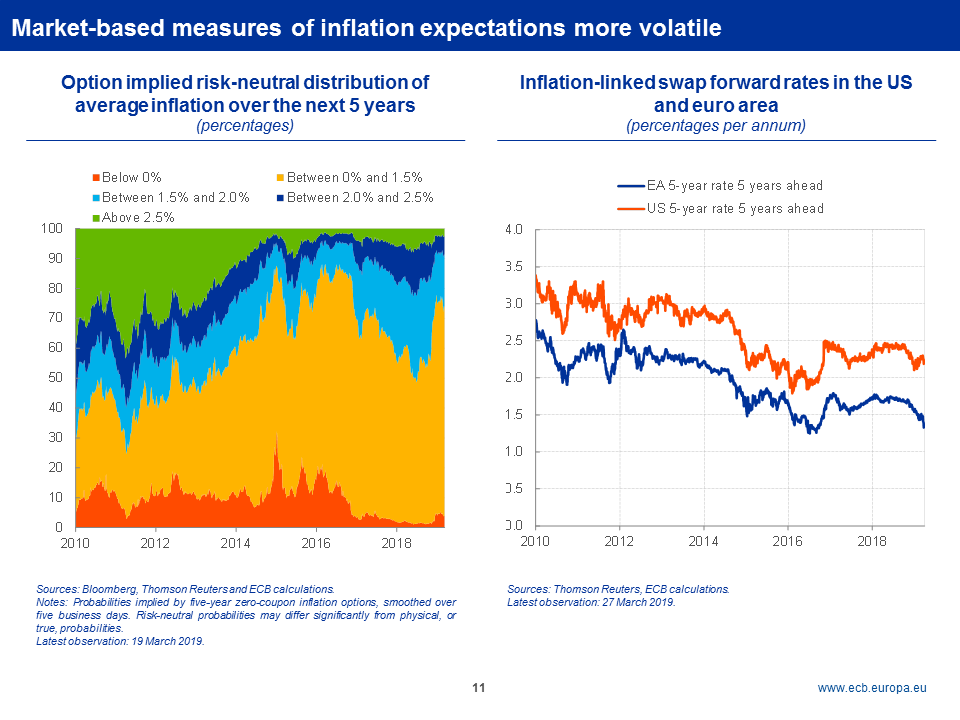

But vulnerabilities remain. Nowhere is this more visible than in market-based inflation expectations. You can see this on the left-hand side of my next slide. According to option prices, the probability that inflation would be between 1.5% and 2% over the next five years fell measurably as the euro area economy weakened over the course of 2018. On the right-hand side you can see that medium-term inflation expectations are currently close to 1.3%, down from 2.5% ten years ago.

This no doubt partly reflects global factors. Inflation expectations in the United States have fallen too. But apart from a short, temporary blip at the end of 2016, the gap between market-based medium-term inflation expectations in the United States and the euro area is the widest it has been for more than four and a half years.

This suggests that idiosyncratic factors are at work too. I would argue, though, that this is unlikely to be related to concerns about the ECB’s credibility.

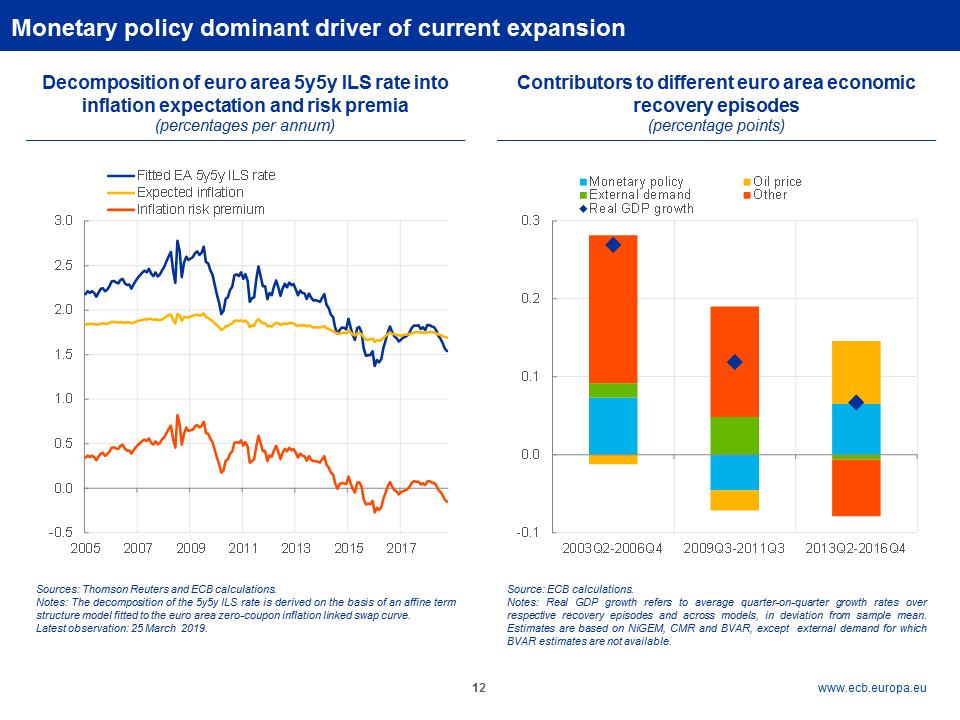

A breakdown of inflation-linked swap rates into expected inflation and an inflation risk premium suggests that medium-term inflation expectations have remained close to levels consistent with price stability. You can see this on the left-hand side of my last slide. This is in line with our reading of survey-based inflation expectations.

Rather, the marked fall in the inflation risk premium suggests that investors assign only a small probability to inflation turning out to be higher than expected. Again, this is a global phenomenon but in my view it is also linked to the unique institutional architecture that sets the euro area apart from other constituencies.[11] It relates to the question of how monetary and fiscal policies can optimally interact and reinforce each other in an environment in which policy space is significantly smaller today than it was before the crisis.

Our response to such concerns should not be to challenge our institutional arrangements. It should not be about blurring the lines between monetary and fiscal policies. Central bank independence, which has clear and indisputable benefits, is a public good that needs protection.

Instead, our response should be about strengthening complementarities.

ECB research shows that, during the early stages of the latest recovery, monetary policy was the dominant driver of growth. You can see this on the right-hand side. Other policies subtracted from growth.

This has changed more recently. The euro area aggregate fiscal stance will be slightly expansionary in 2019, and will thereby support monetary policy. But to do it in a sustainable way, it needs to be adequately distributed: while countries that have fiscal space should use it, in countries where government debt is high, rebuilding fiscal buffers is the best contribution to support the single monetary policy.

And while not all countries have the space to spend more, all have the opportunity to spend better.[12] If fiscal policy preferences contribute to disinflationary concerns – for example, by holding back public investments in education, future technologies and research and development – then they directly counteract the efforts of monetary policy to bring inflation back to levels closer to 2%.

Conclusion

Heterogeneity is part of the euro area’s DNA. It is a source of strength, provided our institutions and markets have the instruments and ability to effectively absorb idiosyncratic shocks. Heterogeneous currency unions need a sufficient degree of private and public risk-sharing, and they need economic policymakers doing their part to preserve and nurture cohesion and convergence. Not doing so means that too much of the burden of macroeconomic stabilisation falls on the ECB, thereby challenging the achievement of its medium-term price stability objective.

Thank you.

- [1]See, for example, ECB (2005), “Monetary policy and inflation differentials in a heterogeneous currency area”, Monthly Bulletin, May.

- [2]See Cœuré, B. (2016), “The ECB’s operational framework in post-crisis times”, speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 40th Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, 27 August.

- [3]See, for example, Trichet, J.-C. (2007), “The euro area and its Monetary Policy”, President’s address at the conference “The ECB and its Watchers IX”, Frankfurt am Main, 7 September; and Trichet, J.-C. (2011), “Two continents compared”, keynote address at the “ECB and its Watchers XIII” conference, Frankfurt am Main, 10 June.

- [4]See Cimadomo, J. et al. (2018), “Risk sharing in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB.

- [5]Also note that the credit channel includes both private and public borrowing, meaning the contribution of private risk-sharing is likely to have been even more negative if one accounts for the establishment of the European Financial Stability Facility/European Stability Mechanism in 2010. Research shows that these institutions made a substantial contribution to the absorption of country-specific shocks. See, for example: Cimadomo, J., Furtuna, O. and Giuliodori, M. (2018), “Private and public risk sharing in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2148, ECB, May; and Milano, V. (2017), “Risk sharing in the euro zone: the role of European institutions”, CeLEG Working Paper Series, No 1701, LUISS University, March.

- [6]See Beyer, A., Cœuré, B. and Mendicino, C. (2017), “The Crisis, Ten Years After: Lessons Learnt for Monetary and Financial Research”, Economie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics, Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), Issue 494-495-4, pp. 45-64.

- [7]See, for example, de Santis, R. and Surico, P. (2013), “Bank lending and monetary transmission in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 1568, ECB, July; and Singh, M. (2014), “Financial Plumbing and Monetary Policy”, IMF Working Papers, No 14/111, International Monetary Fund, June.

- [8]See Ciccarelli, M. and Osbat, C. (eds.) (2017), “Low inflation in the euro area: Causes and consequences”, Occasional Paper Series, No 181, ECB, January.

- [9]See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Convergence matters for monetary policy”, speech at the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet) conference on “Innovation, firm size, productivity and imbalances in the age of de-globalization”, Brussels, 30 June.

- [10]See, for example, ECB (2018), “Country-specific recommendations for economic policies under the 2018 European Semester”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5.

- [11]The importance of monetary and fiscal policy interactions has been well known ever since Sargent and Wallace’s seminal work. See Sargent, T. J. and Wallace, N. (1981), “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Vol. 5, No 3, pp. 1-17. See also Galí, J. and Monacelli, T. (2008), “Optimal monetary and fiscal policy in a currency union”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 76, No 1, pp. 116-132; Beetsma, R.M.W.J. and Jensen, H. (2005), “Monetary and fiscal policy interactions in a micro-founded model of a monetary union”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 67, No 2, pp. 320-352; and Bianchi, F. (2012), “Evolving Monetary/Fiscal Policy Mix in the United States”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 102, No 3, pp. 167-72.

- [12]See ECB (2017), “The composition of public finances in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5; and Coenen et al. (2012), “Effects of Fiscal Stimulus in Structural Models”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 4, No 1, pp. 22-68.

Europska središnja banka

glavna uprava Odnosi s javnošću

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt na Majni, Njemačka

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukcija se dopušta uz navođenje izvora.

Kontaktni podatci za medije