Economic Heterogeneity, Convergence and Monetary Policy in an Enlarged Euro Area

Lucas Papademos, Vice-President of the European Central Bank,

speech delivered at the 7th Biennial Athenian Policy Forum conference “Asymmetries in Trade and Currency Arrangements in the 21st Century”, jointly organised by the University of Giessen, the Athenian Policy Forum and the Deutsche Bundesbank,

Frankfurt am Main, 29 July 2004

Introduction

This important conference focuses on a fascinating topic: “Asymmetries in Trade and Currency Arrangements in the 21st century.” I have been invited to share with you some thoughts on monetary policy in an enlarged European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). There is one presumption and at least one expectation underlying this invitation. The presumption is that the European monetary union is characterized by significant “asymmetries” and that the single monetary policy has “asymmetric” effects on the national economies of the euro area. The expectation is that these asymmetries are likely to increase when more countries join the euro area in the future and, consequently, European policy-makers are likely to face greater challenges in the years to come. I will examine to what extent the presumption is correct and whether or to what extent the expectation is going to prove accurate. I will also discuss their implications for the single monetary policy and for the national economic policies of the euro area countries.

The enlargement of the European Union (EU) by the ten new Member States on 1 May 2004 was a historic event with far-reaching consequences for the size and diversity of the Union. Enlargement has created the world’s biggest unified market that accounts for about one fourth of world trade and global gross domestic product (GDP). In terms of population size, the EU comes third after China and India. With a total of twenty-five Member States, the Union has also become more heterogeneous, not only because of the increased variety of languages and cultural traditions but also because of the greater differences between its members in terms of economic and financial structures as well as living standards. The existence of regional economic differences or asymmetries is not uncommon in economic and monetary unions, including those that were established a long time ago, such as the United States of America. Macroeconomic policies, monetary policy in particular, have been conducted effectively in such unions over a very long period of time. Nevertheless, policy-makers may face challenges depending on the extent of differences in economic and financial structures as well as on the de facto degree of market integration and factor mobility in a large and heterogeneous economic and monetary union.

In my presentation, I will first examine the extent of convergence in the euro area today as reflected in the inflation and output growth differentials between Member States. I will assess in particular the magnitude, causes and persistence of these differentials and consider the implications for the single monetary policy and the national economic policies of euro area countries. Secondly, I will review how the Union’s enlargement has affected the heterogeneity of its economy as shown by several indicators and draw some conclusions on the likelihood that differences in output and inflation dynamics will persist. Finally, I will discuss the expected consequences of the future expansion of the euro area for the conduct and orientation of the single monetary policy, the governance of the Eurosystem, and for the role of national economic policies in enhancing the overall economic performance of the enlarged euro area.

The state of convergence in the euro area: facts and policy implications

Convergence, in a broad sense, can be defined as a process in which differences in economic and financial structures across countries diminish. Differences in the structure and functioning of markets, notably of labor and financial markets, as well as differences in fiscal structures and positions across countries can influence significantly economic dynamics as they have a bearing on the way shocks and the effects of monetary policy are transmitted through the economy. Such structural and fiscal divergences manifest themselves in different output growth and inflation rates across countries. Some degree of heterogeneity has to be considered a natural feature of any monetary union, an integral part of the adjustment mechanism resulting from differing positions in terms of GDP per capita, varied structural features including market adjustment mechanisms, and the effects of asymmetric demand and supply shocks impinging on national economies. While some of these differences reflect given “initial positions” and desirable internal equilibrating processes, others are caused by structural rigidities or the stance of national fiscal policies and they should therefore be tackled by pursuing appropriate policies.

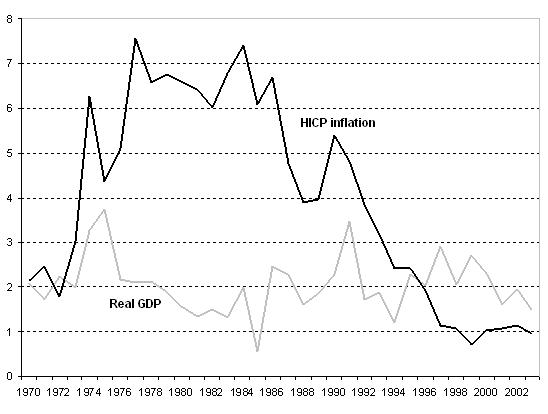

It is useful to start by briefly examining the extent of convergence (or the degree of heterogeneity) in the euro area, as reflected in inflation and output growth differentials. Obviously, aggregate data for the euro area mask differences across the various countries in the monetary union. These differences, however, do not seem to be extremely large either from a historical perspective or in comparison with the experience of other currency unions. The degree of dispersion of output growth across euro area countries in the second half of the 1990s was comparable to that in the previous two decades (see Chart 1). The dispersion of inflation rates is historically low and it is comparable with the one observed in other well-established currency unions, such as the United States. There are signs that the adoption of the single monetary policy has contributed to the cyclical synchronization of growth rates in the euro area. Most visibly, with the establishment of monetary union, not only have we moved to a single short-term interest rate but also long-term interest rates are very closely aligned. Underlying the latter development is a convergence of national long-term inflation expectations across euro area countries.

Chart 1: The dispersion of real GDP growth and HICP inflation across the 12 euro area countries (unweighted standard deviation)

Source: European Commission, Eurostat

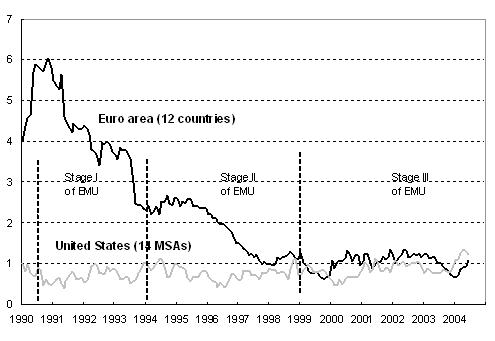

I will now take a more detailed look at the experience with diversity in inflation rates in the euro area during the past decade and, in particular, since the start of EMU. Inflation dispersion (measured by the unweighted standard deviation of inflation rates) began to decline noticeably in the early 1990s, coinciding with the start of the process towards EMU (see Chart 2). Inflation dispersion reached its lowest level in 1999, with the inception of Stage Three of EMU and, since then, it has remained broadly unchanged. In particular, the unweighted standard deviation of inflation rates across euro area countries has remained close to one percentage point since 1999.

Chart 2: The dispersion of annual inflation across euro area countries and the US 14 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) (unweighted standard deviation)

Sources: Eurostat and US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Data up to June 2004 for the euro area and to May 2004 for the US MSAs.

A closer assessment of the extent of inflation differentials across euro area countries at present can be made against some appropriate benchmarks or references. A comparison with metropolitan areas within the United States may provide useful insights. The comparison with other monetary unions, however, is always subject to some caveats and limitations, mostly due to the lack of fully comparable data. Bearing this in mind, the size of inflation differentials across euro area countries since the establishment of EMU has not been very different from that observed in the United States (see Chart 2). It is worth noting, however, that, in contrast to the inflation differentials between regions of the United States, most countries within the euro area have witnessed relatively persistent inflation differentials in recent years.1 To illustrate this point, and focusing on the period since 1999, several euro area countries have witnessed inflation differentials exceeding one percentage point for at least two consecutive years. This has not been the case in the United States. The persistence of inflation differentials therefore seems to be a specific feature of the euro area.

What are the underlying causes of the inflation differentials observed in the euro area? It appears that differences in economic growth and cyclical positions, while undoubtedly relevant, would not suffice to explain the size and persistence of inflation differentials in the euro area. Current inflation differentials can be better explained by a combination of special and structural factors. As to the special factors, which can be characterized as temporary, changes in administered prices and indirect taxes across euro area countries have differed significantly and have thus contributed to the observed inflation differentials.

As regards structural factors that can have long-lasting effects, inflation differentials in some countries have been partly caused by price level and real income convergence, often associated with Balassa-Samuelson effects.2 It is not easy to estimate the size of catching-up effects and to isolate them from the influences of other factors on inflation. In any event, as the process of convergence is progressing among euro area countries, it should gradually lead to a decline in the inflation dispersion caused by price level and income convergence. Other structural factors, such as the degree of wage and price rigidities or the degree of competition in key domestic markets, have also partly contributed to the observed inflation differentials and their persistence.

So what are the policy implications of inflation differentials in the euro area? The single monetary policy of the ECB can only be geared towards the objective of price stability in the euro area as a whole. Just as in any monetary union, inflation differentials in the euro area reflect different regional price dynamics and adjustments in relative prices and in national price levels. These factors cannot be addressed by the single monetary policy. Nevertheless, to the extent that price formation processes diverge across countries, it is useful for monetary policy to take into account the size, persistence and determinants of inflation differentials in assessing area-wide inflation dynamics. In this respect, the ECB’s explicit aim of maintaining euro area inflation below but close to 2 percent over the medium-term is regarded as sufficient to address concerns that some countries would record, on a structural basis, too low inflation rates in a monetary union.3

In assessing the relevance of inflation differentials to the national economic policies of euro area countries, we should first stress that, from a national perspective, the single European monetary policy stance is something given. Whether a national policy response to an inflation differential is needed depends on its cause and persistence. An inflation differential related to the catching-up process does not necessarily call for a policy response. In fact, inflation differentials among countries with different trend growth rates bring about the adjustment of relative price levels that accompanies the catching-up process. Such differentials can be regarded as a means of adjustment and do not call for policy responses as long as convergence in price and wage levels does not outpace convergence in productivity levels. If, on the other hand, positive inflation differentials are associated with loose fiscal policies or wage increases in excess of productivity advances, they could undermine the competitive position of the country concerned. Such differentials, therefore, do require national policy responses that bring about adjustments in the form of below-area average inflation for some time. Such an adjustment process can be painful as it may entail sizeable growth and welfare losses over a period of time. Well-designed structural reforms, particularly measures aimed at removing nominal rigidities and leading to a more responsive wage- and price-setting process in the wake of changing economic circumstances, can facilitate and speed up wage and price adjustments.

EU enlargement, economic heterogeneity and convergence

Looking ahead, what impact would future enlargements of the euro area have on inflation and growth differentials? In answering this question, we should first briefly point to the relevant institutional framework in order to provide the proper perspective. The process of European monetary integration is characterized by a very well-defined multilateral institutional framework. This means that, at every stage of the monetary integration process, major policy decisions concerning one country or currency are collectively made by all EU Member States or by the euro area countries, the European Commission and the ECB Governing Council. The institutional framework aims to guarantee that monetary integration takes place in an appropriate fashion and with the right accompanying policies in place.

The road to the adoption of the euro is a process comprising a number of phases. The first phase for a new Member State is the period after EU accession and before joining the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II). The second phase starts with entry into ERM II and stretches all the way to euro adoption.

On the path to the euro – and to sustainable convergence – the period of ERM II membership is a crucial one. Some countries have already entered this phase. Following the mutual agreement between participant parties, three new Member States, namely Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia joined ERM II on 27 June 2004. More countries are likely to follow. There is no predetermined timing and there are no formal criteria to be met for entry into ERM II. Nevertheless, successful participation in the mechanism depends on a country’s economic situation and its macroeconomic policy strategy and orientation. These must be carefully assessed in the multilateral framework before decisions are taken about the timing of ERM II entry. In some of the new Member States, ERM II is sometimes perceived as a “waiting room” which is almost considered as putting a brake on a desired rapid adoption of the euro. At the ECB, we see it more as a “training room” or a “testing room”, enabling new Member States to prepare their economies for euro adoption and to test the sustainability of the convergence process and of the central exchange rate, which can be chosen as the conversion rate of the national currency to the euro.

Participation in ERM II can be an important means for anchoring exchange rate and inflation expectations and promoting fiscal discipline. It can help orient macroeconomic policies to stability, while at the same time allowing for a degree of flexibility, if needed, through the wide fluctuation band and the possibility of adjusting the central parity. These features can provide the monetary authorities of a Member State that participates in the mechanism with the necessary leeway to deal with disturbances and market-driven volatility, as well as with more fundamental adjustment needs. All of this can help the economy of the country concerned to become more similar to those of the euro area. In this way, ERM II membership provides a useful framework within which convergence (nominal and institutional) can be advanced ahead of eventual entry into the euro area. The length of the period of ERM II participation that might be needed to achieve the necessary degree of convergence depends on the policies pursued and may extend beyond the required minimum period of two years.

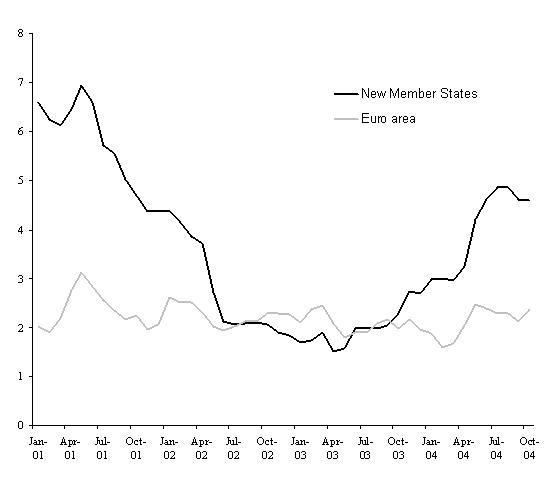

Once a Member State has demonstrated that it has attained the necessary high degree of convergence in a sustainable manner, by fulfilling the criteria stipulated in the Maastricht Treaty, it can enter the euro area. For some countries, that might not be too far away. In order to get a first idea of the potential economic landscape in an enlarged euro area, a look at the current European Union of 25 Member States provides useful insights (see Table 1). While such an approach has obvious limitations, as future euro area members will make further progress in convergence before they adopt the single European currency, it is still an informative starting point. Inflation rates in most of the new Member States have come very close to the euro area average, so that one might be tempted to conclude that the impact of enlargement in terms of inflation differentials may not be a major one. However, while average inflation in the new Member States was very close and, at times, slightly below euro area levels from mid-2002 to early 2004, it has increased significantly, resulting in a positive inflation differential of about 2 percentage points at the end of the second quarter of 2004 (see Chart 3). This is mainly due to changes in indirect taxes and administered prices as well as increases in food prices, which are still very important items in the consumer basket of many of the new Member States. A key feature of the latest EU enlargement is that new Member States show greater differences from each other than the EU-15. A number of new Member States have already achieved low inflation, while some others are still in the process of completing disinflation. This partly explains the current inflation differentials across the new Member States. These are presumably of a temporary nature, as the new EU entrants are committed to pursue price stability as the primary objective of monetary policy.

Table 1: Key characteristics of the EU-25 (2002, unless indicated otherwise)

| EU-15 | EU-25 | USA | JAPAN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (mln., 2004) | 381 | 455 | 291 | 128 |

| GDP ( % of world GDP) † | 26.8 | 28.1 | 32.5 | 12.3 |

| GDP (€ bln.) | 9,172 | 9,615 | 10,980 | 4,235 |

| GDP in PPP terms | 8,921 | 9,741 | 9,422 | 3,067 |

| GDP per capita (€ thous.) | 24.0 | 21.1 | 37.7 | 33.2 |

Source: ECB Monthly Bulletin, May 2004.

†GDP shares are based on country GDPs in current US dollars, average 2002.

Chart 3: Inflation in the euro area and the new Member States. Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP, annual percentage changes)

Source: Eurostat (HICP is weighted by nominal GDP in 2002).

Despite the general progress towards price stability in recent years, maintaining low inflation or, in some cases, completing the disinflation process will be a challenging task for a number of new Member States. Especially in countries where inflation is still high, the lasting reduction of inflationary pressures and the attainment of price stability will require continuous efforts and the implementation of stability-oriented macroeconomic policies and structural reforms. In fact, the recent rise in inflation – even from relatively low levels – could make some economies vulnerable to wage-price spirals and adversely affect inflation expectations. The adoption of sound macroeconomic policy frameworks and objectives, along with the implementation of prudent wage policies, is crucial in this respect.

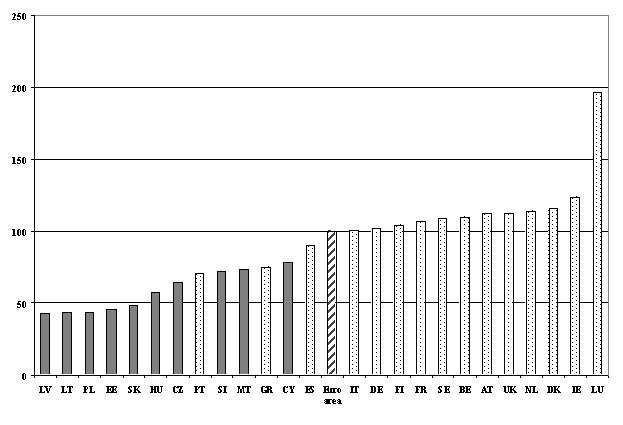

In terms of other economic indicators, the differences between the new Member States and the euro area are relatively big compared with previous enlargement rounds (see Charts 4 and 5). This is particularly true with regard to GDP per capita and price levels. Although sizeable in terms of overall population (around 75 million people altogether compared with around 380 million in the EU-15), the GDP of the new Member States is relatively small compared with that of the EU-15. Income dispersion in the EU has increased significantly since 1 May 2004 (see Chart 6). In terms of purchasing power parity, GDP per capita in the new Member States relative to that of the enlarged EU, is on average slightly below 60 percent, ranging from 43 percent in Latvia to 78 percent in Cyprus and compared with 71 percent in Portugal, 75 percent in Greece and 124 percent in Ireland. These differences are even more striking when market exchange rates are used rather than purchasing power parities.

Chart 4: Real GDP growth and inflation in the EU-25 (annual average percentage changes in 2003)

Source: Eurostat

Chart 5: Budget balances and public debt levels in the EU-25 (as a percentage of GDP in 2003)

Source: Eurostat, Fiscal notification and debt data for 2003.

Chart 6: Comparison of per capita GDP in the EU-25 in 2003 (Euro area = 100) (in purchasing power parity terms)

Source: Eurostat

According to economic growth theory, GDP in low-income countries tends to grow faster than in richer ones, provided the former adopt appropriate policies. This proposition reflects, inter alia, the relatively high marginal return on capital in poorer, less capital-abundant countries. It should therefore be expected that growth differentials would increase in the EU and, indeed, this has been the case (see Chart 7). From 1996 to 2003, the new Member States posted average annual real GDP growth of 3.6 percent compared with around 2.0 percent in the euro area. Output growth differentials are even higher when we compare the figures for individual countries. In 2003, for example, annual real GDP growth rates ranged from a buoyant 9.0 percent in Lithuania or 7.5 percent in Latvia to virtually no growth in Germany (-0.1 percent) or even a decline in output in Portugal (-1.2 percent) and the Netherlands (-0.7 percent).

Chart 7: Real GDP growth in the euro area and the new Member States (Quarterly data, annual percentage changes)

Source: Eurostat

Furthermore, on the heels of faster economic growth, most new Member States tend to experience wider output fluctuations (see Chart 8). For the ten countries as a whole, the average standard deviation of real GDP growth was 2.4 percentage points in the period from 1996 to 2003, significantly higher than that in the euro area (around 1.3 percentage points). The larger output variability is associated with relatively high investment ratios in the new Member States, and the tendency of capital spending to be more cyclical than consumption and more exposed to changes in investor sentiment. Past fluctuations in growth may have also been caused by profound structural changes and reforms, which have sometimes progressed at a rather uneven pace over the last 15 years, and/or have been due to macroeconomic stabilization programs and external shocks, such as those triggered by the Russian crisis in 1998.

Chart 8: Average real GDP growth in selected EU countries and its standard deviation: 1996-2003 (annual percentage changes)

Source: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Overall, the size of the existing gap in per capita GDP, combined with the current and expected pace of the catching-up process, suggests that real GDP growth differentials are likely to persist for a fairly long period of time and could continue after the adoption of the euro. This conclusion is based on the assessment that the differences in output dynamics are largely a reflection of the structural features of the economies concerned. It should be pointed out, however, that the new EU members have adjusted their economic structures to bring them more in line with those of the “older” EU members and have already achieved a fairly high degree of economic integration with them. For instance, economic structures have become rather similar in terms of the share of agriculture, industry and services in GDP. In particular, the agricultural sector’s share has shrunk to around 5 percent of GDP in the ten new Member States, compared with around 2.3 percent in the euro area and 2.1 percent in the EU-15, while the industrial sector (including manufacturing and construction) accounts for 27 percent of GDP, the same as in the euro area. Individual countries, however, continue to display sizeable differences with respect to the distribution of employment across production sectors. Finally, the new Member States are highly integrated in terms of trade with the euro area, which has by now become their main trading partner, and display shares of trade with the euro area that compare well with those of the “older” Member States.

Monetary policy in an enlarged euro area

The preceding review of key macroeconomic features of the expanded EU clearly shows that the Union’s recent enlargement has made it economically more heterogeneous. This is not necessarily a bad thing. It has to be kept in mind that differences in trend growth rates are a necessary feature of the process of convergence of GDP per capita, and eventually also of price levels in the longer run. Nevertheless, questions have been raised whether persistent and sizeable inflation and output growth differences will strain the cohesion of the euro area, and whether they could affect the conduct and effectiveness of the single monetary policy. For the prospective members of the euro area, waiving the right to implement an independent monetary policy as a stabilization instrument is likely to entail welfare losses if this occurs prematurely, that is, at an early stage of the convergence process. Moreover, inappropriate national economic policies within a monetary union may accentuate cyclical fluctuations and result in boom-bust cycles. In my view, the concerns that have been expressed about potential tensions in an enlarged euro area and about the conduct of the single monetary policy are largely unfounded. Let me explain why.

As emphasized previously, a new Member State can adopt the euro only after it has achieved a high degree of nominal convergence with the euro area, in accordance with the provisions of the Maastricht Treaty. The stipulations of that Treaty also require that nominal convergence be sustainable, which implies that it should be underpinned by a sufficient degree of structural, or real, convergence; in other words, that the economic structure of a prospective euro area member should have converged sufficiently towards the prevailing structures in the euro area. From a broader perspective, real and nominal convergence are – and should be regarded as being – complementary. Stable prices and inflation expectations anchored to price stability support growth, low unemployment and a high level of prosperity. Consequently, by the time the new Member States adopt the euro, the degree of convergence in a wider euro area would be comparable to the one currently observed. The economic environment within which the single monetary policy will be conducted should not differ appreciably from the existing one.

It cannot be excluded, however, that after a country has achieved a high degree of nominal convergence, maintaining it may prove to be a challenge. For example, divergences in inflation rates could increase after the enlargement of the euro area, if wage increases exceed productivity gains, owing to aggregate demand pressures or labor market rigidities. Substantial and persistent fiscal slippages would also jeopardize the hard-won progress towards stability. This points to the importance of achieving a high degree of sustainable convergence prior to entering the euro area and to maintaining it thereafter.

The new Member States with catching-up economies may face the additional challenge resulting from relatively fast productivity growth in their tradable sectors compared with the EU average which may translate into somewhat higher inflation, associated, among other things, with the Balassa-Samuelson effect. Although most empirical studies indicate that this effect has, thus far, accounted for only a small part of these countries’ inflation differentials vis-à-vis the euro area, there is evidence that such an effect is present in a number of these economies.4 Moreover, its significance could increase in the years to come if productivity growth in the new Member States were to accelerate as a consequence of EU membership.

While the impact of future euro area entrants on the area’s economic and monetary aggregates should not be overstated, given that the GDP of the new EU countries amounts to around 6 percent of the euro area GDP, a divergence of their inflation rates following the adoption of the euro would entail specific risks for these countries. To minimize such potential risks it is, first of all, important to “lock in” the irrevocably fixed conversion rate of a new entrant’s currency against the euro with a reasonable degree of certainty about the long-term fair value of that currency’s exchange rate. Second, and related to the previous point, the costs and benefits of giving up monetary policy as a stabilization tool have to be weighed very carefully by the policy-makers of a prospective participant in monetary union when deciding about the timing of its entry. Third, a sound public finance position is essential to allow a participating country’s fiscal policy to serve the objective of short-term macroeconomic stabilization and, at the same time, play an appropriate role in supporting real GDP growth and welfare in a sustainable manner. Given the substantial fiscal imbalances in several new Member States at the current juncture, attaining fiscal consolidation in a timely manner is a particularly important and challenging task. These three considerations underline the significance of determining the right timing for a country’s entry into the euro area.

For all these reasons, the ECB has stressed the importance of two points: first, that both the Maastricht convergence criteria and the Stability and Growth Pact are cornerstones of a successful participation in the euro area, and second, that economic structures and institutions should be conducive to a sustainable achievement of stable macroeconomic conditions. The new Member States will benefit from the adoption of the euro as a result of reduced interest rate premia and the elimination of the risk of speculative attacks. Ultimately, however, it is in their own interest to ensure that they have achieved a sustainable degree of convergence – sustainable well beyond the time of euro adoption – so as to make sure that the benefits of joining EMU will be maximized.

The enlargement of the euro area also has consequences for the governance of, and decision-making in, the Eurosystem. Much has been written about the impact that the participation of the central bank governors from the new Member States in the Governing Council could have. The views expressed are related, on the one hand, to the “mechanics” of decision-making, and, on the other hand, to the substance of the Governing Council’s monetary policy deliberations and decisions.

In order to ensure that, after the enlargement of the euro area to more than 15 countries, decisions continue to be taken in a timely and efficient manner, the EU introduced new voting modalities for the ECB’s Governing Council, based on a recommendation from the ECB.5 The new voting system will cap the number of voting rights in the Governing Council at 21: six permanent voting rights for the members of the Executive Board, and 15 for the governors of national central banks, who will exercise their voting right on the basis of a rotation system (see Chart 9). Governors will be allocated to three groups and will exercise their voting right with different frequencies, based on a country ranking determined by an indicator of the relative size of the economy and the financial sector of the respective countries. Therefore, national central bank governors from larger countries will exercise their voting right more frequently than those from smaller countries. In this way, the new voting modalities also ensure that, in any given period in time, the governors with a voting right are from Member States which – taken together – are representative of the euro area economy as a whole.

Chart 9: Voting modalities in an enlarged ECB Governing Council

Source: ECB Monthly Bulletin

Admittedly, the new voting system is not simple. Any rotation system, however, is inevitably characterized by a degree of complexity. The relative complexity of this system is a consequence of the aim to fulfill simultaneously a number of principles, in particular the “principle of representativeness”. It is interesting to note that the new voting system of the Governing Council of the ECB is rather similar to that of the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve System in the United States.

Concerns have been expressed that the notion of “representativeness”, which is embedded in the rotation system, might introduce an element of “re-nationalization” into the ECB’s decision-making. This brings me to the second issue raised earlier. It has been argued that especially if economic divergences between different parts of the euro area were to persist in the future, there would be an increased risk that national central bank governors in the Governing Council would act more as national representatives. Two brief responses to this argument. First, the indicator of the relative size of the economies of governors’ “home countries” is an auxiliary device which is used exclusively to determine who votes when. Second, in decision-making – and that is crucial for substantive reasons – the principle of ad personam participation of governors remains valid and the “one member, one vote” principle applies to all Governing Council members exercising a voting right. These principles and features of the new voting system will ensure that, also in a future enlarged Governing Council, it is the force of argument that will count in the deliberations and not the country of origin of a governor or its size.

An additional point that should be made regarding monetary policy in an enlarged euro area relates to communication. Effective communication of policy decisions is an important and challenging task for any central bank. It is likely to be even more so in a future enlarged euro area: to explain to the public and market participants the policy decisions taken for the wider euro area as a whole and, more generally, to explain the role of monetary policy in ensuring price stability and fostering economic growth. This is particularly significant with respect to countries and regions where economic divergences – such as above average inflation and unemployment rates or lower than average output growth – are very pronounced or persistent. It should, therefore, be explained convincingly that in a monetary union, fiscal and structural policies are key to address regional divergences and help sustain competitiveness and employment in participating countries. To this end, it is crucial that further progress is made in implementing the structural reforms envisaged in the EU’s Lisbon agenda (announced in 2000) to improve the functioning of product and labor markets. Attaining the goals of the Lisbon reform agenda will clearly contribute to the successful performance of an enlarged and more diverse euro area in the future.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, let me briefly respond to a variant of the usual question posed to policy-makers in a monetary union: Can an enlarged European Union thrive as a monetary union, in which a “one size” monetary policy has to “fit all”? My answer is definitely positive. The governance structure and the technical infrastructure of the Eurosystem are ready for an expanded monetary union. Moreover, prospective euro area members will have achieved the necessary degree of convergence for the adoption of the single European currency, thus ensuring their successful participation and the effective functioning of monetary union itself. The framework, orientation and conduct of monetary policy in an enlarged euro area will not differ from the present one: the single monetary policy will ensure the preservation of price stability in the expanded euro area as a whole. In any single currency area – be it a monetary union or a single country – monetary policy cannot and must not try to reduce inflation differentials across regions. But, depending on the sources and the nature of such differentials, national remedies may be needed to prevent them from leading to developments which are harmful for the countries concerned. Ultimately, however, the economic performance of the monetary union and of its members will depend on their ability to function flexibly, and adjust efficiently and in a timely manner to changing market conditions and external shocks. As many of the new Member States have economies characterized by considerable flexibility and adaptability, their future participation in the euro area, following the attainment of sustainable convergence, could help enhance the expanded euro area’s productivity and competitiveness and thus create a more favorable economic environment for the conduct of the single European monetary policy.

Notes

For a general examination of inflation differentials in the euro area, see ECB (2003a). On the role of inflation persistence, see, for example, Angeloni and Ehrmann (2004), and Ortega (2003).

For the original contributions on this topic, see Balassa (1964) and Samuelson (1964).

The issue of inflation differentials has also been addressed in the discussions about the ECB’s monetary policy strategy. See Issing (2003).

See, for example, Kovács (2002).

For a more detailed presentation, see ECB (2003b).

References

Angeloni, I. and Ehrmann, M., (2004), “Euro Area Inflation Differentials”, ECB Working Paper, No. 388, September, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

Balassa, B., (1964), “The purchasing power parity doctrine: a reappraisal”, Journal of Political Economy, December, 72, 584-596.

European Central Bank, (2003a), Inflation differentials in the euro area: potential causes and policy implications, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

European Central Bank, (2003b), “The adjustment of voting modalities in the Governing Council”, Monthly Bulletin, May, 73-83.

Issing, O., (ed.), (2003), Background studies for the ECB’s Evaluation of its Monetary Policy Strategy, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

Kovács, M. A., (2002), “On the estimated size of the Balassa-Samuelson effect in five Central and Eastern European countries”, National Bank of Hungary Working Papers, No.5 (based on contributions by the Czech National Bank, National Bank of Hungary, National Bank of Poland, National Bank of Slovakia and Bank of Slovenia), Budapest: National Bank of Hungary.

Ortega, E., (2003), “Persistent inflation differentials in Europe”, Banco de España Documento de Trabajo, No. 0305, Madrid: Banco de España.

Samuelson, P., (1964), “Theoretical notes on trade problems”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 46, 145-154.

Europska središnja banka

glavna uprava Odnosi s javnošću

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt na Majni, Njemačka

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukcija se dopušta uz navođenje izvora.

Kontaktni podatci za medije