Asset purchases, financial regulation and repo market activity

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the ERCC General Meeting on “The repo market: market conditions and operational challenges”, Brussels, 14 November 2017

Let me thank the organisers for inviting me here today.[1]

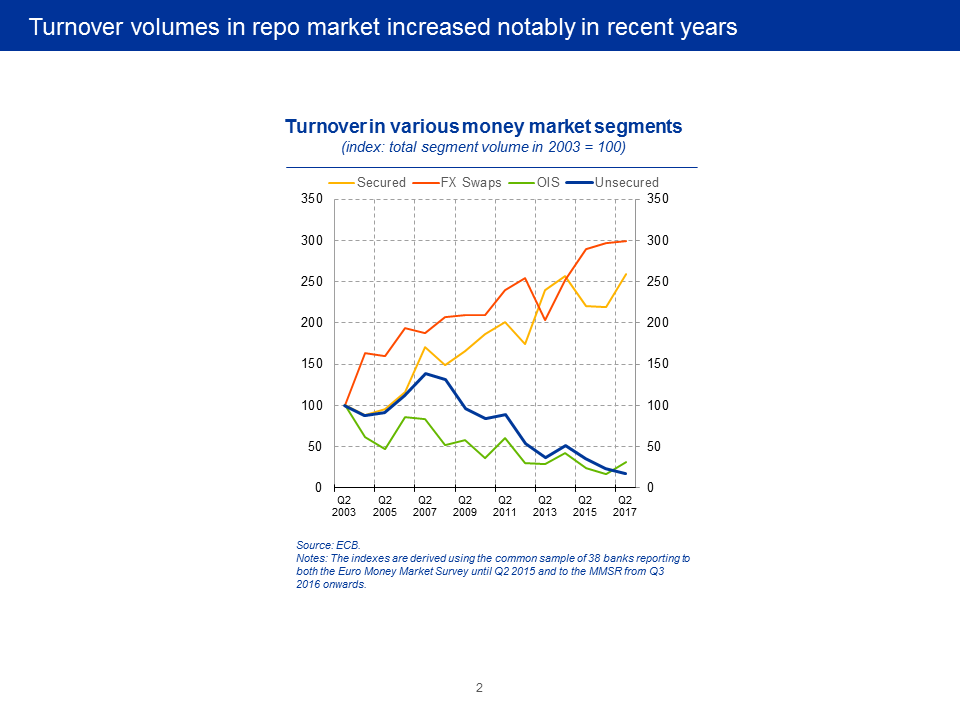

The repo market is a cornerstone in the transmission of monetary policy. In its traditional role, it is a prime short-term funding market for banks. Before the outbreak of the global financial crisis, secured transactions accounted for around a third of the daily turnover in euro area money markets according to money market statistical reporting (MMSR) data. Today, their share is closer to two-thirds.

Movements in short-term repo rates therefore change the market-based financing conditions for banks and, hence, their conditions for trading with their ultimate customers – firms and households. This means that repo rates are a prime channel through which changes in the monetary policy stance are transmitted to the broader financial market and the real economy.

In addition, the repo market plays an important intermediation role in the financial system by being the main vehicle for sourcing and financing government bonds. In this role, the repo market critically supports the liquidity of the bond market. It offers investors the possibility to finance long positions and to borrow securities to deliver into short positions. Interruptions in the repo market may therefore affect the entire term structure of interest rates.

The implication is that central banks need to have a watchful eye on developments in the repo market to ensure that it transmits and reflects the intended monetary policy stance. This includes monitoring the impact of their own actions on repo market activity, as well as the effects of other, external factors that could potentially drive a wedge between central banks’ own intentions and actual financial market conditions.

In fact, two watchful eyes are not too many, in view of the risks that this market may pose to financial stability. Because repo trades are predominately of a very short-term nature, and secured funding can create a false sense of security when collateral prices are in fact often procyclical[2], excessive reliance on repo market funding may quickly turn into a source of instability for the financial system as a whole. The scars from the great financial crisis are still visible today.

In my remarks today I would like to discuss two factors that have recently been highlighted by market observers, practitioners and academics alike as potentially challenging the intermediation capacity of repo markets, namely central bank asset purchases and post-crisis prudential regulation.[3]

I will show that the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP) left a visible footprint in the repo market, but that last year’s modifications to our securities lending facility contributed to restoring an appropriate balance between ensuring the effectiveness of our measures and the smooth functioning of repo markets. I will also provide empirical evidence that challenges the view that financial regulation has adversely impacted repo market activity so far. But I will also argue that further evidence is needed to draw conclusions on this matter.

Asset purchases and repo market activity

Let me start with the impact of central bank asset purchases on recent repo market activity.

Asset purchases may have two broad effects on repo markets. The first is their impact on excess liquidity. With central banks exchanging large amounts of reserves for longer-dated securities, banks may no longer need to tap the interbank market, both secured and unsecured, to manage their short-term liquidity needs. As a result, trading volumes may fall.

The second effect is closer to one of the main transmission channels of asset purchase programmes, namely portfolio rebalancing. In imperfect financial markets, those in need of scarce securities, or those who have a special preference for them, need to bid harder to obtain them, thereby pushing up their price and lowering their yield – which then delivers financial conditions supportive of higher output and prices in the real economy. There is growing empirical evidence that this channel has been very effective in the euro area.[4]

The flip side to this is that, although purchases are conducted in the secondary cash market, price adjustments in this market can also be expected to affect conditions in the repo market. A simple way to think about this is through short-selling. Bonds being richer in the cash market will make it more difficult to borrow them via reverse repos. This should also push up the price in the repo market, all else equal.

In addition, investors who own more expensive securities should be able to profit from them by obtaining lower funding costs in the repo market. In other words, because the cash and the repo market often intermediate the same asset, it is natural that changes in one market may have repercussions in the other.[5]

Both effects have clearly left a footprint in the repo market. But one needs to look beyond aggregate data to understand the full impact of the ECB’s APP.

For example, there has been no overall fall in average euro repo market turnover since the great financial crisis. Daily volumes in the repo market even rose in recent years, despite the considerable increase in excess liquidity. You can see this clearly on my first slide. According to MMSR data, turnover was close to €350 billion daily in the second quarter of this year, up from around €250 billion a few years ago.

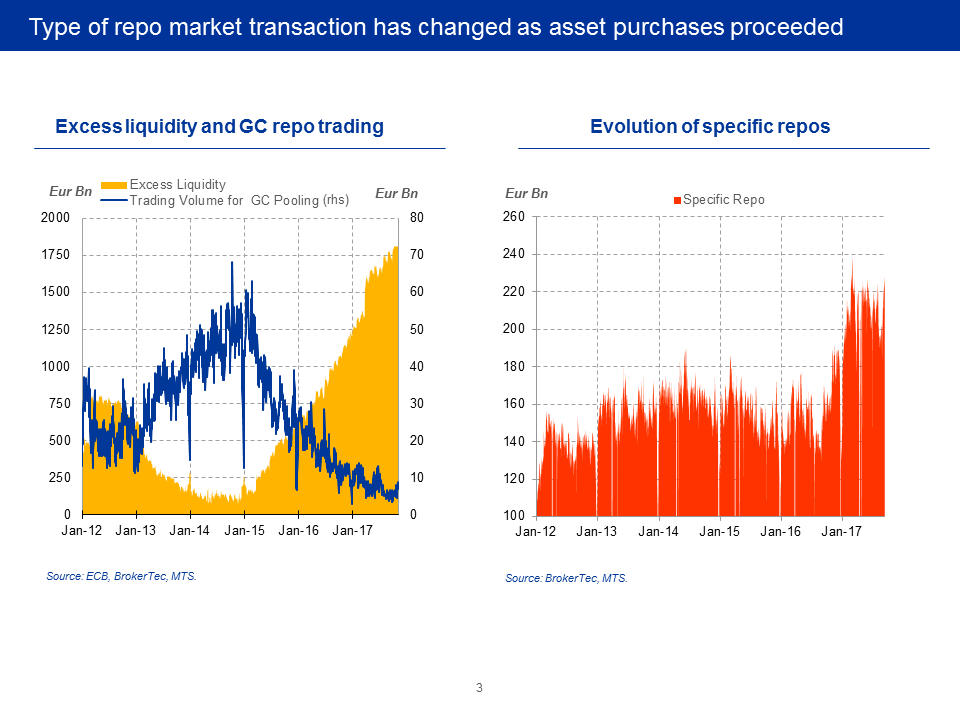

What has changed, however, is the type of transaction executed in the repo market. This you can see clearly on this slide and on the next. First, there has been a clear shift from unsecured to secured transactions since the crisis. Second, as can be seen on the next slide, increasing excess liquidity has led to a notable decline in the share of trades backed by general collateral (GC), which is traditionally used to obtain funding for cash management purposes. This may suggest that proceeds from the sales of securities, together with the ECB conducting its main refinancing operations at fixed rate full allotment, have increasingly acted as a substitute for funding in the interbank market.

At the same time, we have observed an appreciable increase in collateral-driven or specific repos. You can see this on the right-hand side. In other words, repos are increasingly conducted as a means to move securities among market participants, not primarily to raise cash.[6]

There might be several reasons for this. Smaller inventories held by market-makers after the crisis, for example, may cause them to source bonds in the repo market more often. Alternatively, short-selling activity may have increased, a phenomenon often observed at, or close to, monetary policy turning points when investors expect yields to rise.

One factor that is likely to have contributed to the rise in special repos is policy-induced scarcity, however. This can best be seen when considering the German Bund market. Here, our purchases have absorbed a multiple of net issuance in recent years, meaning that we have actively reduced the stock of outstanding bonds held by private market participants.

The consequence is that investors in search of these securities increasingly need to pay a premium, a specialness premium, which, broadly speaking, reflects the costs of the difficulty in finding a lender of the security. The premium will then depend on the scarcity of the underlying asset and their holding structure: many of the residual government bond holders are unwilling to sell them, or will sell them at a higher price due to regulation or their own asset-liability management rules.

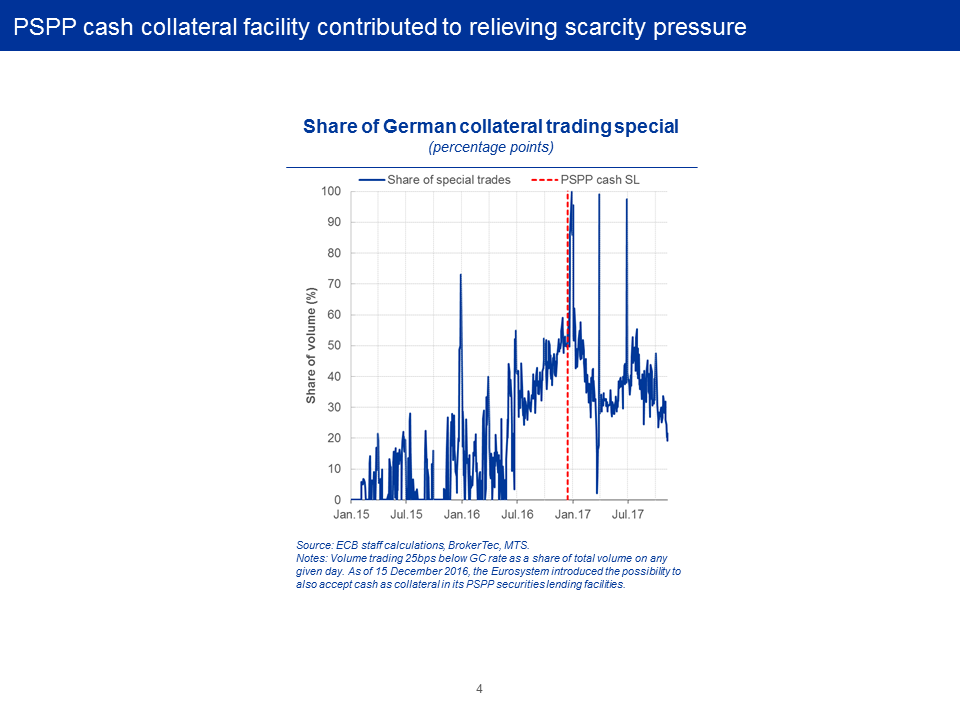

You can see this on my next slide. Our asset purchases have coincided with a notable increase in the share of German bonds that trade “special” in the repo market, meaning they trade at a premium over GC rates. Before we started our purchases, typically less than 5% of bonds in the German repo market were trading special. In the second half of last year, this share increased to more than 50%. Year-end events, which I will come back to later, pushed their share even higher.

You can also see that specialness did not increase immediately with the start of our purchases under the public sector purchase programme (PSPP) in March 2015. The reason might be related to potential non-linearities in the way supply changes affect market outcomes. That is, price effects from the flow of purchases may only become visible the moment supply effectively starts to constrain demand.

Reverse supply effects are also clearly visible on the same chart. When the ECB Governing Council, in December last year, decided to also accept cash as collateral in our securities lending facility, we effectively increased the supply of bonds available in the repo market, thereby swiftly reducing the share of bonds trading special.[7]

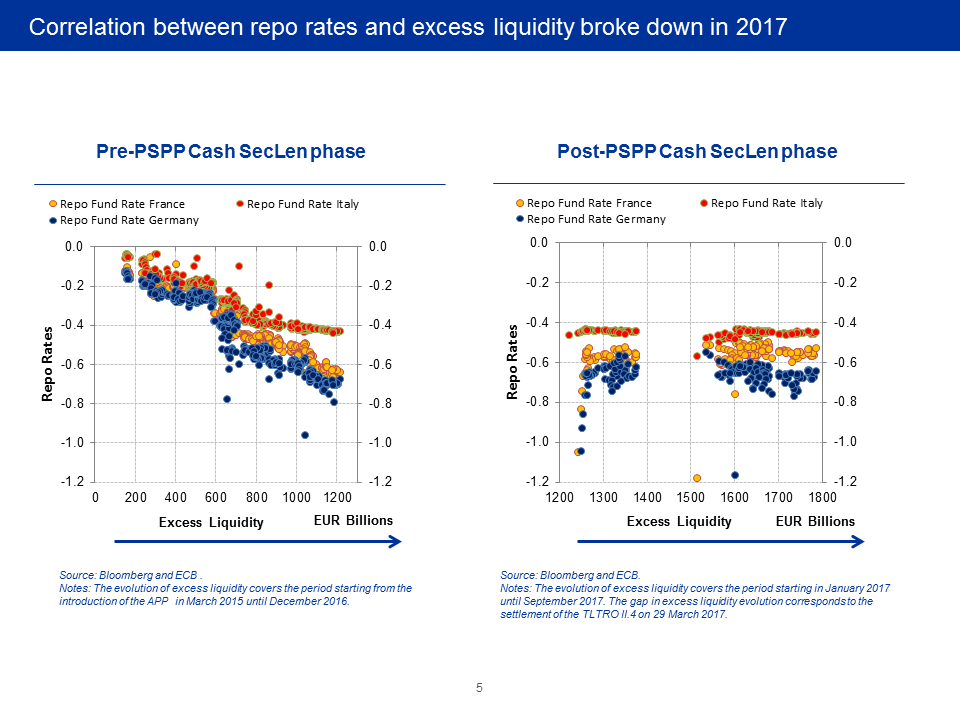

The price effects of this decision can be seen on the next slide. Before we accepted cash as collateral, there was a strong positive relationship between the level of excess liquidity and repo rates, not only for trades backed by German collateral, but also for those involving French and, to a lesser extent, Italian securities. The moment we amended our securities lending facility in December last year, the relationship broke down, as you can see on the right-hand side.

Recent ECB analysis confirms the intimate relationship between cash and repo markets and the impact of supply and demand effects.[8] The authors estimate that a 1% reduction in the effective supply may increase specialness, on average, by up to five basis points. Studies for the US market come to qualitatively similar conclusions.[9] In other words, whether a bond trades special, and by how much, depends crucially on its effective supply, which is itself affected by factors such as the amount of investors that are willing to lend out securities in the repo market.

These effects are also found to be persistent. You can see this on the same slide. The “scarcity” premium stabilised in spite of continuously increasing excess liquidity, but did not regress. In other words, continued scarcity in the cash market implies that the remaining holders of bonds continue to benefit from lower financing conditions. You can also see this on the previous slide. In 2017, looking through the occasional ups and downs, around 30% of the bonds continued to trade special.

The objective of our decision to also accept cash in securities lending was, therefore, not to prevent all instances of specialness. Put simply, this would have meant acting in the cash market or to sterilise bond purchases, which would run counter to our desired monetary policy stance. The present inflation outlook requires financing conditions to remain accommodative for a considerable period of time.

Our objective was rather to support smooth repo market functioning, also with a view to avoiding episodes of extreme specialness, such as at the end of a year or quarter. Extreme specialness may result in serious market malfunctioning, with investors choosing to strategically fail to deliver. It is therefore fair to say that the initial restriction – only lending bonds against other PSPP-eligible securities – was too penalising and is likely to have contributed to the growing specialness premium in the segment of the yield curve where the Eurosystem was intervening most heavily last year.

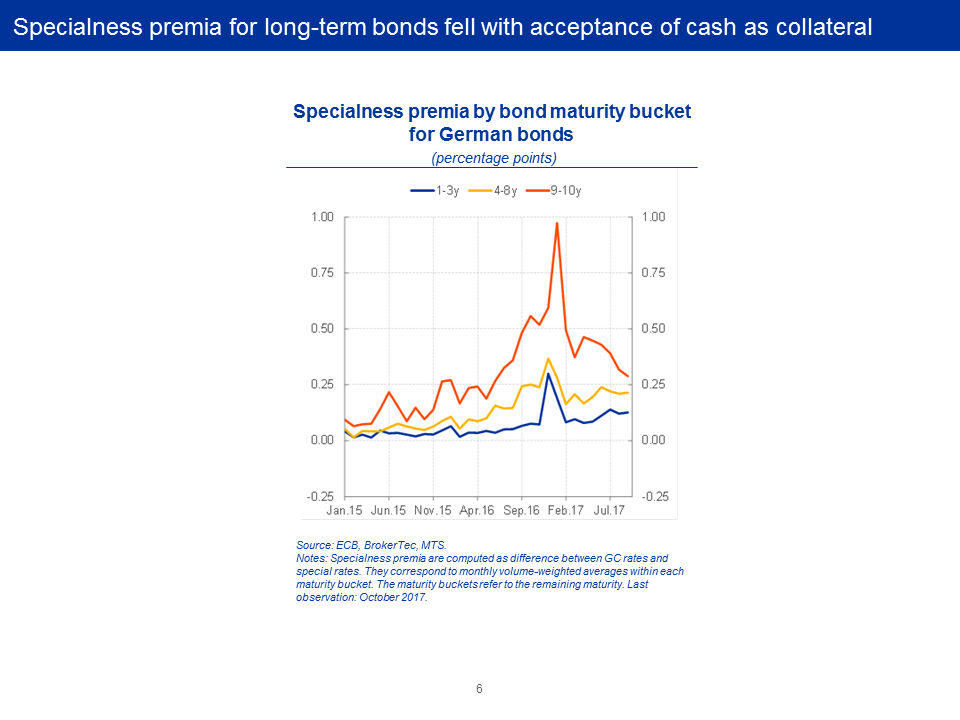

You can see this on the next slide. Purchases under the PSPP in Germany have long been concentrated in medium to long-term maturities due to the restriction, at that time, not to conduct purchases below the deposit facility rate (DFR). Increasing scarcity in that segment of the cash market then also translated into a persistent rise in the specialness premia of such bonds, even when abstracting from year-end effects.

Our decision to accept cash as collateral in securities lending, and to allow purchases below the DFR, contributed to relieving this pressure. Premia across maturity buckets are now broadly similar. The relatively low specialness premia for bonds with shorter maturities, in turn, also suggests that the majority of holders of such bonds – mainly non-euro area investors without access to our deposit facility, as I illustrated in a previous speech – were, and remain, generally willing to provide them in sufficient quantity in the repo market.[10]

Yet, this chart also reinforces the point I made earlier about the flow and stock effects of our purchases: with the effective supply of bonds gradually shrinking over time as a result of our purchases, specialness premia have been persistently inching upwards.[11] While stock effects reinforce one of the key transmission channels of the APP by increasing the “value for money” – the bang for the buck – of new net purchases in terms of their impact on financial conditions, we also need to be mindful that a shortage of government bonds may over time adversely affect the intermediation capacity of repo markets.

There are two reasons for this. First, government bonds are the main type of collateral used in repo markets, primarily because of their safety and liquidity. According to MMSR data, euro area government bonds represent more than 80% of the collateral used. Second, the supply of safe private collateral is necessarily scarce[12], while the supply of safe public collateral has fallen on account of both a decline in net issuance and the downgrades in sovereign credit ratings. For example, the share of euro area bonds rated AAA by at least two rating agencies has fallen from levels around 60% before the great financial crisis to around 20% today. In other words, safe debt is in short supply and debt in long supply is less safe.[13]

This is also why the Governing Council’s decision of 26 October, when it decided to extend the horizon of its asset purchases by another nine months, and to reduce the pace of monthly purchases to €30 billion, emphasised the contribution of the stock of acquired assets, together with forthcoming reinvestments, to providing continued monetary support.

Financial regulation and repo market activity

Asset purchases are not the only factor affecting supply and demand conditions in cash and repo markets. This brings me to the second part of my remarks. As you know, a number of liquidity regulations affecting banks, such as the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) and the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), require banks to hold a sufficient quantity of high-quality liquid assets.

At face value, these regulations could be expected to have contributed to bumping up demand for government bonds, thereby reinforcing the effects of the ECB’s APP. But because, as a result of our asset purchases, banks hold a large amount of central bank reserves, which count as high-quality liquid assets, such regulations are unlikely to have been a key driver of increasing collateral scarcity.

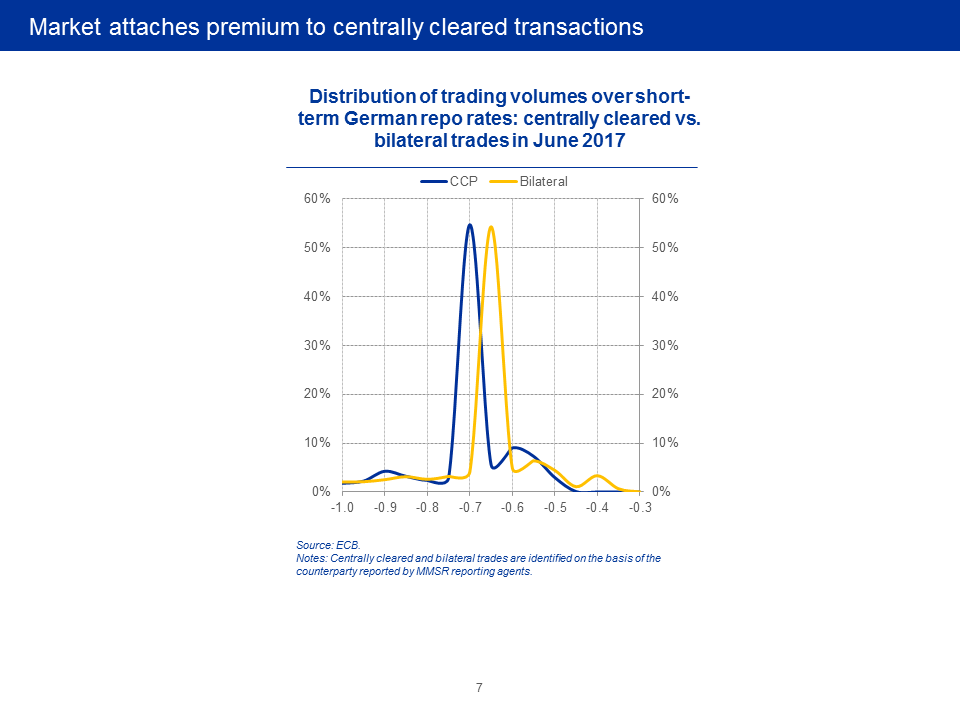

These reforms, however, are likely to have affected the repo market in different ways. One of them you can see on my next slide. Here I show the distribution of repo market activity for one-day tenor contracts exchanged bilaterally or via central clearing counterparties (CCPs) for German collateral. The chart shows an interesting feature, namely that the market attaches a premium to centrally cleared transactions.

The reasons for this are unlikely to surprise you: the leverage ratio allows for offsetting cash proceeds to be netted off when the transactions are with the same counterparty, have the same end date, and are conducted in the same settlement system. This means that although repo transaction are not part of the 2009 Pittsburgh central clearing mandate, which covers OTC derivatives, centrally cleared transactions have a premium because they make those trades less capital intensive compared with non-nettable ones. According to MMSR data, around two-thirds of repo transactions are already cleared centrally.

So, what we seem to have observed so far is that the leverage ratio – contrary to much-voiced concerns – has not led to a reduction in repo volumes, but rather to a change in the way trades are settled. And to the extent that these trades are increasingly intermediated through CCPs, this is clearly a positive development. CCPs reduce counterparty and systemic risks and help clearing members economise the use of scarce collateral.[14] There is also empirical evidence that clearing increases market resilience in periods of stress.[15]

Resilience of trading volumes to regulatory reforms is also confirmed by empirical analysis conducted by ECB staff – the results of which will be published in the ECB’s financial stability review on 29 November. I will offer a short preview today.

In this report, ECB staff assess the effects of recent regulatory reforms on repo market developments at quarter-end, based on supervisory data for a sample of more than 50 banks directly supervised by the euro area’s single supervisor. Micro data are important to ensure that aggregate repo market developments do not mask a significant impact of regulatory reforms at the individual bank level.

The findings suggest that, although banks’ adjustments to higher leverage ratios seem to be somewhat correlated with a reduction in their repo volumes, the effects are not found to be economically meaningful relative to other exposures. Other regulatory measures, such as the LCR or the NSFR, are found to have had no statistically significant impact so far on repo volumes. The study also highlights that the more significant falls in banks’ outstanding repo volumes at year-end are likely to have also been driven by additional factors, such as contributions to the single resolution fund or national bank levies.

These findings are not the final word on the matter, of course. The repo market is in a state of transition as the report by a study group of the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS), chaired by Bank of England Deputy Governor Jon Cunliffe, recently concluded. In this respect, the CGFS also recommended in April that a further study on repo markets be undertaken within the next two years.

This means that policymakers will continue to closely monitor developments in repo markets and financial markets more generally. Some effects can only be thoroughly assessed once the reforms have been implemented more meaningfully, while others may become clearer at an earlier stage. For example, it seems undisputable that regulatory reforms have contributed to temporary volatility in repo market activity on reporting dates.

Specifically, window-dressing behaviour of banks appears a likely unintended effect of regulation. I would therefore encourage further analysis of methods that could help reduce volatility and thereby contribute to a smoother functioning of markets. In this respect, you will have seen in a recently published Opinion of the ECB on, inter alia, amendments to the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), that the ECB supports the review of the calculation method for the leverage ratio.[16]

I have also previously voiced support as CPMI Chair for implementing the leverage ratio in a way that does not create disincentives for centrally cleared transactions, namely by offsetting the initial margin in the case of derivative exposures related to client clearing.[17]

All these exercises, however, should not be mistaken for tolerance of a relaxation of regulation. Post-crisis reforms aim to curb excessive leverage and reliance on short-term wholesale funding, and for good reasons. This is also why the Financial Stability Board (FSB) has published specific recommendations, including a framework for minimum haircuts for securities financing transactions (SFTs).[18]

The FSB has also assessed the potential financial stability risks related to collateral re-use in SFTs.[19] The latter may contribute to a build-up of leverage and increase interconnectedness among market participants. The FSB concluded that regulatory reforms, in particular the leverage ratio and the liquidity requirements, are important to mitigate these risks.

This means that the implementation of the Basel III reforms will have effects on repo markets, as intended. These might look undesirable from an institution-perspective but they will have system-wide benefits.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The repo market is undergoing significant change. Regulation is forcing market participants to re-examine the extent of their engagement and make more efficient use of their balance sheets. This adjustment process coincides with central banks worldwide adopting a series of unconventional monetary policy measures that have also affected the nature and scope of repo market activity.

Some of these effects will prove temporary, others more permanent. Their full impact can only be assessed in earnest once markets have fully transitioned to their new steady state. From a central bank perspective, it is important to ensure that our own measures do not adversely affect the intermediation capacity of repo markets. Our decision in December last year to also accept cash as collateral in our securities lending facility has proven very effective in this respect. It contributed to mitigating risks of extreme specialness, while preserving the effectiveness of our policy measures in the pursuit of our price stability objective.

At the same time, a high degree of persistence in repo specialness lends support to the idea that the stock of securities already held by the ECB is likely to be a powerful channel through which our measures can help preserve accommodative financing conditions, even after the end of our net asset purchases.

Thank you.

[1] I would like to thank Riccardo Costantini for his contribution to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

[2] See Gorton, G. (2012), “Securitized banking and the run on repo”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 104(3), pp. 425-451; and Holmstrom, B. (2015), “Understanding the role of debt in the financial system”, Bank for International Settlements, Working Paper No 479, January.

[3] See Committee on the Global Financial System (2017), “Repo market functioning”, CGFS Papers, No 59; and International Capital Market Association (2015), “Perspectives from the eye of the storm: The current state and future evolution of the European repo market”.

[4] See e.g. Altavilla, C., G. Carboni and R. Motto (2015), “Asset purchase programmes and financial markets: lessons from the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No 1864; Andrade, P., J. Breckenfelder, F. De Fiore, P. Karadi and O. Tristani (2016), “The ECB's asset purchase programme: an early assessment”, ECB Working Paper No 1956; and Blattner, T.S. and M. Joyce (2016), “Net debt supply shocks in the euro area and the implications for QE”, ECB Working Paper No 1957.

[5] For a theoretical disposition, see Duffie, D. (1996), “Special Repo Rates”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 51(2), pp. 493-526.

[6] See e.g. International Capital Market Association (2017), “European Repo Market Survey”, No 33, October.

[7] Securities purchased under the PSPP have been made available for securities lending in a decentralised manner by Eurosystem central banks since 2 April 2015. As of 8 December 2016, Eurosystem central banks have the possibility to also accept cash as collateral in their PSPP securities lending facilities without having to reinvest it in a cash-neutral manner. The aim of securities lending is to support bond and repo market liquidity without unduly curtailing normal repo market activity. The Eurosystem is primarily targeting market participants with market-making obligations and is monitoring the securities lending activities closely so as to ensure the ongoing effectiveness of the arrangements. In September 2017, securities on average worth €60 billion were lent out by the Eurosystem, of which around €15 billion were lent out against cash as collateral. For further details please see the section Securities lending.

[8] See Corradin, S. and A. Maddaloni (2017), “The importance of being special: repo markets during the crisis”, ECB Working Paper No 2065. The authors study the case of ECB SMP purchases of Italian sovereign bonds in the second half of 2011. The SMP portfolio was strictly buy-to-hold and purchased securities were not lent out.

[9] See D’Amico, S., R. Fan and Y. Kitsul (2014), “The scarcity value of Treasury collateral: Repo market effects of security-specific supply and demand factors”, Finance and Economics Discussion Series Paper No 2014-60; and Jordan, B.D. and S.D. Jordan (1997), “Special Repo Rates: An Empirical Analysis”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 52(5), pp. 2051-2072.

[10] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Bond scarcity and the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the Club de Gestion Financière d’Associés en Finance, Paris, 3 April.

[11] One should note here the difference between the development of repo funds rate and the average specialness premia after our decision to also accept cash as collateral in securities lending. While the former stabilised, the latter continued to increase.

[12] Ongoing efforts to recreate safe, transparent and consistent securitisation may, to some extent, support the supply of safe private collateral.

[13] Against this background, rebalancing the euro area fiscal stance towards faster debt reduction in high debt jurisdictions, and using fiscal space where it is available, would yield benefits for the supply of safe collateral.

[14] See e.g. Corradin, S., F. Heider and M. Hoerova (2017), “On collateral: implications for financial stability and monetary policy”, ECB Working Paper No 2107.

[15] See e.g. Mancini, L., A. Ranaldo and J. Wrampelmeyer (2015), “The Euro Interbank Repo Market”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 29(7), pp. 1747–1779.

[16] See the Opinion of the European Central Bank of 8 November 2017 on amendments to the Union framework for capital requirements of credit institutions and investment firms (CON/2017/46).

[17] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “The known unknowns of financial regulation”, panel contribution at the conference on Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy IV, Washington D.C., 12 October. See also the ongoing FSB-led review of incentives to centrally clear, the Derivatives Assessment Team (DAT).

[18] See FSB (2015).

[19] See FSB (2017).

Europska središnja banka

glavna uprava Odnosi s javnošću

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt na Majni, Njemačka

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukcija se dopušta uz navođenje izvora.

Kontaktni podatci za medije