Challenges for the Euro at ten

Speech by Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBat the conference ‘The Euro at ten: Governing the Eurozone in a globalised world economy’, Berlin, 8 December 2008

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, [1]

It is for me a great honour, and a pleasure, to have been invited here today to speak about the current state of the euro area, and the challenges it faces. In little more than three weeks, we will celebrate the tenth anniversary of the creation of the Euro. The decision to establish European Monetary Union was - as you know - not uncontroversial. During the years leading up to EMU, indeed, several commentators offered gloomy projections on the viability of the common currency, with the range of predictions going from the swift break-up of the monetary union in the face of the first breeze, to the possibility that EMU might even lead to conflicts among member states. The experience of the last ten years - and especially the dramatic events of the last several months - have clearly shown the full extent to which such predictions were misguided.

First, since January 1999 the Euro has guaranteed to hundreds of millions of people the same extent of price stability which had traditionally been associated with the strongest among its constituent currencies. Second, the common currency has effectively protected euro area countries from both the inflationary impulses originating on world food and energy markets, and, since August 2007, the worst financial storm since the end of the 1920s. The success of the Euro along this second dimension is testified by the simplest, and most telling indicator of all: as widely reported in the financial press, in several European countries which had not previously contemplated joining EMU, the financial crisis has led to significant shifts in public opinion in favor of Euro adoption. It is during tough economic times such as those we are currently going through that both the benefits of belonging to a strong and stable currency area, and the dangers of ‘going it alone’ in an economic environment which is prone to sudden and violent swings, become fully apparent. The Euro is only ten years old, but with the current crisis it is truly coming of age.

Today I will discuss the main accomplishments of European Monetary Union, and I will then elaborate on the challenges faced by the euro area, both within the current conjuncture, and from a longer-term perspective.

1. Key accomplishments of European Monetary Union

- SLIDE 1 -

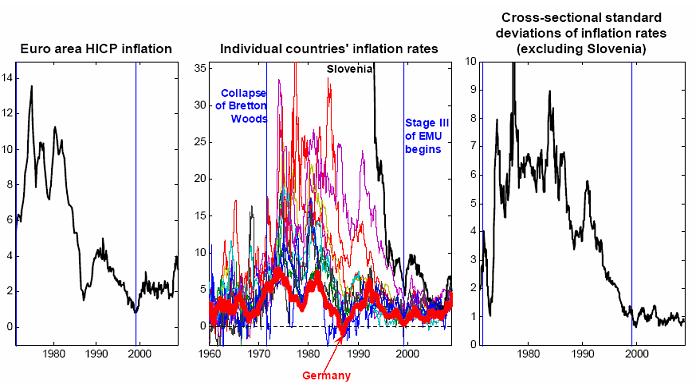

Figure 1 provides a clear illustration of a key accomplishment of EMU showing aggregate euro area HICP inflation since the collapse of Bretton Woods in August 1971. It also shows individual inflation rates for the 15 countries which, as of today, belong to the monetary union; and the evolution of the cross-sectional standard deviation of inflation rates among these countries [2] as a simple measure of heterogeneity of their inflationary experiences.

As apparent from the chart, after showing some signs of instability during the years leading up to the collapse of Bretton Woods, inflation increased dramatically after 1971, reaching, at the euro area-wide level, a peak of 13.6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 1974. Moreover, cross-sectional dispersion of inflation rates reached a peak in excess of 9 per cent in the second half of the 1970s.

Starting from the first half of the 1980s, the disinflation process was characterized by a decrease in both individual countries' inflation rates, and the extent of their cross-sectional dispersion. Under EMU, euro area inflation has been equal, on average, to slightly more than 2 per cent, and has been, by historical standards, remarkably stable.

This inflation stabilisation under EMU has been accompanied by two further key developments: first, the disappearance of inflation persistence, defined as the tendency for inflation to deviate from the central bank’s price stability objective following a shock, rather than quickly reverting to it; and second, the stabilisation of inflation expectations, with the disappearance of an impact of actual inflation outcomes on agents’ expectations, which is a clear indication of the credibility of our price stability objective. I briefly elaborate on both issues.

Recent ECB research [3] has shown that, after January 1999, inflation persistence has disappeared both at the aggregate, euro area-wide level, and within its three largest countries (Germany, France, and Italy). Further, similar changes have affected inflation dynamics in several inflation-targeting countries and in Switzerland under the ‘new monetary policy concept’, whereas they have been largely absent in the United States and Japan, two countries characterised by a committment to price stability but lacking a clearly-defined nominal anchor. As a result, in the euro area, Switzerland, and inflation-targeting countries, inflation dynamics is - as of today - essentially purely forward-looking, whereas in countries such as the United States and Japan it still retains a significant backward-looking component.

What explains these findings? The simplest and most logical explanation is that credible and clearly defined nominal anchors, by providing a ‘focal point’ for agents’ inflation expectations, have rescinded the link between such expectations and past inflation outcomes, which was instead inevitable during historical periods in which such anchors either were absent or were not regarded as credible. This conjecture is indeed compatible with the stylised fact previously mentioned: the stabilisation of inflation expectations under EMU.

Several recent studies [4] suggest that the introduction of explicit numerical targets for inflation has anchored inflation expectations, that means making them essentially unresponsive to actual macroeconomic developments - in particular, to past inflation outcomes. Beechey, Johannsen, and Levin (2007), for example, show that long-run inflation expectations are more firmly anchored in the euro area than in the United States. They show that macroeconomic news have significant effects on U.S. forward inflation compensation - even at long horizons - whereas they only influence euro area inflation compensation at short horizons.

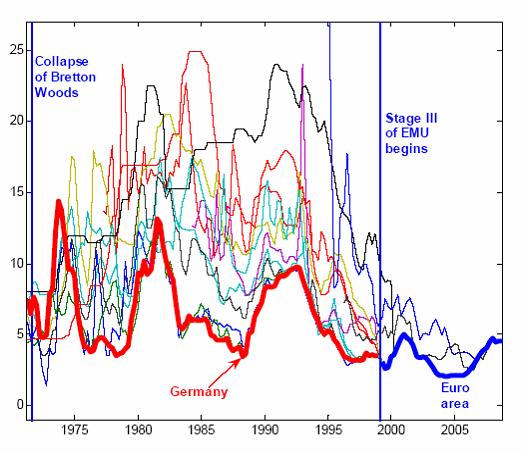

- SLIDE 2 -

Low and stable inflation, and the firm anchoring of inflation expectations, have automatically led to another fundamental achievement of European Monetary Union: historically low interest rates, with all the accompanying benefits for both consumers and firms, in terms of lower borrowing costs. [See Figure 2]

Overall, European Monetary Union has been associated with a remarkable stabilisation of the nominal side of the economy, with low and stable inflation, well-anchored inflation expectations, and historically low and stable nominal interest rates. A question that naturally arises is: ‘Did the stabilisation of the nominal side of the economy come at the expense of developments on the real side?’ As I will now discuss, empirical evidence clearly rejects such a notion along several dimensions.

- SLIDE 3 -

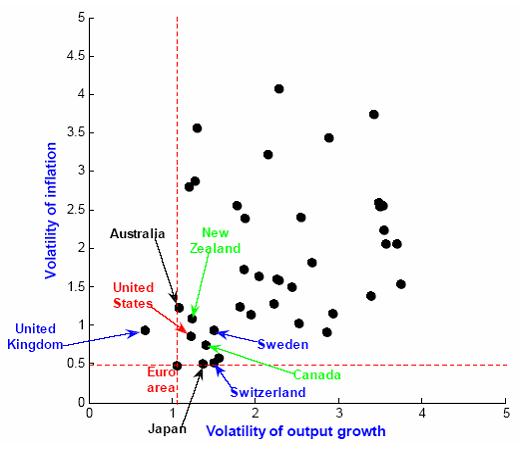

Figure 3 shows a scatterplot of the standard deviations of annual CPI inflation and real GDP growth for the euro area, the United States, and 47 other countries since the beginning of European Monetary Union. [5] As the figure makes clear, the performance of the euro area has been remarkable. First, the standard deviation of euro area inflation, equal to 0.5 per cent, has been the lowest of the sample, with only Switzerland and Japan close, but slightly higher. Second, the volatility of output growth, at 1.1 per cent, has been the second lowest of the sample after the United Kingdom, which has however exhibited a markedly higher volatility of inflation, equal to 0.9 per cent. Third, the comparison with the United States—which, being a monetary Union of roughly similar economic size, provides the most natural benchmark - is uniformly positive, with the U.S. volatilities of inflation and output growth equal to 0.9 and 1.2, respectively. The evidence reported in Figure 3 therefore suggests that the stabilisation of the nominal side of the euro area economy has not been achieved at the expense of the real side. Rather, the opposite appears to be true, with both the real and the nominal side exhibiting an excellent performance from an international perspective.

Indeed, macroeconomic stabilisation has been accompanied by a remarkable performance in terms of job creation. First, from January 1999 until the end of 2007, the number of people employed in the euro area has increased by 15.7 million, compared with an increase by only about 5 million during the previous nine years; second, under EMU the unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest level since the early 1980s. The improvement in euro area labour market’s performance reflects corporate restructuring, wage moderation in most countries, and—crucially—the progress made on structural reforms associated with the Lisbon process. As I will come to in a moment, a lot of progress in this dimension is – of course - still possible and needed.

A further benefit of the introduction of the Euro has been the strengthening of trade and financial linkages across euro area countries. First, the sum of intra-euro area exports and imports increased from around 31% of GDP in 1998 to about 40% in 2007. Second, the Euro has been fostering a gradual portfolio reallocation away from holdings of domestic financial instruments, and towards holdings of financial instruments issued elsewhere within the euro area. Euro area cross-border holdings of long-term debt securities, for example, have markedly increased from about 10% of the overall stock at the end of the 1990s to nearly 60% in 2006. Notably, euro area residents have also almost doubled the amount of cross-border holdings of equity issued within the area, from 15% in 1997 to 29% in 2006. Well-integrated euro area financial markets, and well-diversified asset portfolios, decrease the extent to which the saving and spending decisions of firms and households depend on economic and financial developments in a specific country, region or sector. As a consequence, credit and risk-sharing channels are increasingly contributing to attenuate the impact of shocks within a specific euro area country or sector.

Summing up, nearly ten years after the start of European Monetary Union, the common currency has to be regarded as an unqualified success, guaranteeing macroeconomic stability to hundreds of millions of European citizens, and shielding them from the direst consequences of the macroeconomic shocks which—especially in recent months—have been affecting the world economy. Many challenges however remain. I will devote the next part of my speech to long-term challenges, and I will then turn to current issues.

2. Long-term challenges

The long-term success of European Monetary Union crucially depends on four key issues: first, increasing the long-term growth potential of the euro area; second, making the euro area economy more flexible and more competitive; third, pursuing sound fiscal policies; and fourth, the completion of the single market. I will discuss these issues in turn.

Although the euro area economy’s stability under EMU has been remarkable, its performance in terms of average growth rates has been less impressive. Since the beginning of the 1990s, euro area real GDP growth has been equal, on average, to 2.1 per cent, compared with 2.8 per cent in the United States. Since the beginning of EMU, the annual growth rate for the euro area has averaged 2.2 per cent per year, compared with 2.7% in the US. A key reason for the euro area’s moderate performance is the comparatively low trend growth in labour productivity. Whereas in the 1980s, the average annual growth rate of labour productivity was equal to 2.3 per cent, in the 1990s it declined to 1.8 per cent, and between 1999 and 2007 it further decreased to 1.2 per cent. By contrast, over the same periods average U.S. hourly labour productivity growth accelerated from 1.2 to 1.6, and then to 2.1 per cent. What lies at the origin of these differences in labour productivity developments in the two areas? Specific policies targeted at increasing employment - in particularly for the unskilled segment of the labour market - certainly contributed to the decrease in labour productivity growth in the euro area. Labour supply developments, however, can only explain a minor fraction of the overall deceleration in labour productivity growth, with the dominant portion being instead due to a significant slowdown in total factor productivity growth (or TFP growth), which is generally taken as a measure of technological progress, and of improvements in the organisation and overall efficiency of all the factors of production. Average TFP growth in the euro area, indeed, was equal to 1.6 per cent in the 1980s, and it declined to 1.1 per cent in the 1990s and to 0.7 per cent between 1999 and 2007.

What explains such difference between the United States and the euro area in terms of average TFP growth? The consensus among economists points towards a clear edge, on the part of the United States, in exploiting advances in information and communication technology (ICT), due largely to a favourable regulatory environment, a superior ability to redesign management and organisational systems, the relative ease of reallocating, retraining, and shedding workers, and continued investment in research and development (R&D). In 2006, the fraction of R&D investment relative to GDP in the euro area was only 1.9 per cent, compared with 2.7 per cent in the United States. This is a first dimension along which improvements ought to be made. It is also necessary to intensify cooperation between industry, universities, and public sector research institutes, in order to raise the efficiency of public R&D spending. As for investment in human capital, in several euro area countries its rate of accumulation is still insufficient, in particular when compared with the needs of contemporary, knowledge-intensive economies. The effectiveness of the accumulation of human capital should be enhanced at all stages of the education process, by improving the quality and efficiency of our schools and universities, and should be continued through lifelong training and learning.

A further step ought to be increasing competition in both labour and product markets, thus providing strongest incentives to invest and innovate, and to ultimately boost productivity. More generally, it is necessary to support a more innovative and entrepreneur-friendly economic environment. Europe needs to create an environment which is more apt at fostering new and dynamic firms willing to reap the benefits of opening markets and to pursue creative or innovative ventures. Finally, a key requirement is for firms to be able to access relatively easily the finance they need. From this point of view, the euro area significantly lags behind the United States, with its venture capital financing, expressed as a fraction of overall GDP, being equal to a fraction of what it is in the U.S..

Turning more specifically to the labour market, the comparative rate of growth of working-age population is one of the key factors explaining differences in real GDP growth between the euro area and the fastest growing industrial economies. Over the last two decades, for example, the average contribution to real GDP growth from growth of the working-age population has been approximately 0.8 percentage point higher in the United States than in the euro area. Looking ahead, the euro area faces the prospect of an ageing population, so that the labour force could become an important constraint on trend growth.

Turning to labour utilisation, in spite of subdued growth in working-age population, over the last ten years there has been a significant increase in the total number of hours worked in the euro area. This stands in contrast to developments in the United States, where a small deceleration has taken place. A significant portion of the acceleration in the euro area can be explained by an increase in labour utilisation, and in particular by improvements in both participation and employment rates. Despite this progress, however, there is still room for improvements in the workings of European labour markets. First, the employment rate in the euro area is still low by international standards. Second, the rate of unemployment in the euro area is still high, in particular in some individual countries. In particular, whereas the employment rate for prime-age males in the euro area is comparable to that in the United States, significant disparities between the two areas remain concerning the youth, female and older segments of the labour force. For example, in 2007 the female employment rate was 58 per cent in the euro area, compared with 66 per cent in the United States, whereas the employment rates for older workers were 43.3 and 61.7 per cent, respectively. Finally the youth employment rates in the two areas were 38 and 54.2, respectively.

In spite of significant achievements in job creation over the most recent years, both the still comparatively high unemployment rates in the euro area, and the low participation rates in some countries, point towards the need to stimulate both the supply and the demand sides of the labour market. Concerning labour supply, further reforms in income tax and benefit systems would contribute to increase incentives to work, especially for those segments of the labour force characterised by a weaker attachment to the labour market, such as women and older workers. Concerning labour demand, it is necessary to reduce labour market rigidities, in particular those restricting wage differentiation and wage flexibility, which negatively impact upon the hiring especially of younger and older workers. Under this respect, in several euro area countries progress towards greater contractual flexibility has been comparatively slow, and employment protection legislation—especially for permanent contracts—remains quite rigid.

Beyond increasing flexibility, another key challenge for the euro area is improving its competitiveness. In this respect, a key issue is keeping the dynamics of unit labour costs firmly under control to prevent or correct abnormal deviations. In situations in which such deviations appear, it is of paramount importance that social partners and national governments take swift action in order to address wage developments that go beyond productivity increases, so that unit labour costs in those economies increase less rapidly than the euro area average.

The third key long-term challenge is the commitment to sound fiscal policies and, thereby, to implement the Stability and Growth Pact. There are several reasons why sound fiscal policies are a crucial prerequisite for the monetary union’s long-term success. First and foremost, they are needed in order to minimise the risk of fiscal policy spillover, both into monetary policy and, more generally, across countries. Further, they are needed to increase the flexibility and adaptability of the economy. Sound fiscal policies, for example, are a necessary condition for flexibility, thus dampening business-cycle fluctuations through the workings of automatic stabilisers.

The final challenge pertains to the full completion of the Single Market, which will not only increase competition and efficiency, but also improve adjustment mechanisms in the face of adverse shocks. Under this respect, in spite of the fact that the single market was already a goal of the founding fathers of the European Union—as set out in the Treaty of Rome—there is still significant progress to be made. According to the OECD, for example, product market regulation is still high in several euro area countries, and the extent of regulation in the euro area considered as a whole is still significantly higher than in the United States.

Let me now turn to a key challenge that we are currently facing, namely how EMU deals with the current developments in financial markets.

3. Current challenges

The world economy is currently going through the most dramatic crisis since the 1930s. The factors leading up to the current turmoil were excessive growth in global credit, and historically high leverage in the financial system as well as in the non-financial sectors of some countries. Excessive credit growth and inordinately high levels of leverage, however, are not a product of nature: rather, they were the product of a specific time and of specific regulatory frameworks. In fact, the developments since August 2007 were also the outcome of minimal, or ‘light touch’ regulation - or even the circumvention of regulation at all - which in the views of some went so far as to maintain that markets could essentially ‘self-regulate’.

Therefore, I believe – and this will be an important challenge for the coming years - that the current episode will ultimately lead to a new intellectual consensus on the proper boundaries between governments and markets, first and foremost concerning the most appropriate regulation of financial markets.

Working within such a system in flux, policymakers around the globe are now battling the consequences on the real economy of the strongest recessionary winds since the financial market collapse of the end of the 1920s. The situation is made especially complex by a combination of several different problems which - even taken in isolation, by themselves - would be sufficient to create significant challenges for policymakers. Let me briefly discuss the most important among them.

First of all, there is the painful realisation, on the part of consumers in several countries, that the economic strength that they had come to regard as ‘natural’ over the last several years seems not sustainable. To a significant extent, such strength was largely based on borrowing: borrowing against houses whose prices has been artificially inflated by bubbles and borrowing by accumulating credit card debts. Today, household in several countries have found themselves burdened by staggering amounts of debts, which prevent them from consuming precisely at a time when their consumption would be most needed to cushion the economy from the winds of recession.

Within such an environment of retrenching consumption expenditure, having well-functioning financial markets, and a strong banking system, would be of paramount importance in order to smooth out the impact on the economy. But since early August 2007 the financial sector has been engulfed by an even more serious crisis, which has required policymakers to intervene to a previously unthinkable extent. The crisis has shown the benefits of belonging to a strong and stable currency area. As a consequence, the current crisis has led to a radical reassessment of the desirability of joining the Euro on the part of policymakers, financial market participants, and citizens in several countries outside the euro area.

The recent crisis has clearly shown the fundamental role played by central banks in crisis management, through the provision and management of liquidity in the money markets and - in some exceptional cases - by providing emergency liquidity to individual institutions. In this respect, the ECB’s money market operations have consistently been based on the fundamental principle of separation of the monetary policy stance from liquidity management. The former is determined in the light of the primary objective of maintaining price stability over the medium term. The latter’s goal, on the other hand, is minimising financial stability risks, and ensuring the orderly functioning of money markets. The provision of unlimited liquidity to the euro area banking system on the part of the ECB, against an expanded array of eligible collateral since mid-October, should effectively eliminate concerns about liquidity risk, and should therefore further reduce pressures in the money markets. Central banks’ actions, however, can only go so far, as they cannot tackle some of the underlying causes of tensions on the money markets, first and foremost concerns about counterparty credit risk, and the continuing uncertainty on banks’ other funding sources and capital positions. In this respect, the measures taken by the governments and shareholders are, therefore of paramount importance, and should address these problems over time. Moreover, it is key to ensure that there is access to financing for all sectors of the economy, especially for small and medium sized enterprises, which cannot access the capital market so easily

4. Concluding remarks

I would like to conclude by recalling some important points which ought to be kept in mind in order to reinforce the strength and resilience of the euro area economy, thus contributing to preserve and consolidate the remarkable success of the Euro. First and foremost is the need to proceed along the path of structural reforms, with the firm implementation of the Lisbon strategy, as refocused and reinforced by the EU Council. This is crucial to increase the euro area’s growth potential, foster job creation, and increase the resilience of the economy in the face of shocks. A second key issue is the need to regularly monitor developments in unit labour costs across euro area countries. In particular, in those countries which have witnessed sizeable cumulative increases in unit labour costs above and beyond the euro area average, with the resulting loss in competitiveness, it is essential that all social partners fully understand the importance of cost and price moderation within the context of the Monetary Union. Third, it is of crucial importance - especially within the current uncertain environment - to preserve the public’s trust in the soundness and long-term sustainability of fiscal policies. And fourth, it is important to get the regulatory response right. Market participants cannot go back to the business models of the 60s and 70s. However, the regulatory and institutional framework for the financial sector as well as business models, risk taking and corporate governance should be reviewd with and open mind in the interest of long term prosperity and stability.

Let me close with a positive note by emphasizing that it is important to remember the benefits the Euro has brought to hundreds of millions of people: low inflation and low interest rates, macroeconomic stability, and – at the current juncture – has given protection against some of the potential consequences of the worst financial storm since the end of the 1920s. Let me re-assure you that ECB will stand up to the challenges we are facing to continue achieving our main goal of maintaining price stability in the euro area as part of the European policy agenda to preserve and reinforce the success of the euro.

Thank you very much for your attention.

References

Beechey, Meredith J., Benjamin K. Johannsen, and Andrew T. Levin (2007), ‘Are Long-Run Inflation Expectations Anchored More Firmly in the Euro Area than in the United States?’, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2008-23

Benati, Luca (2008), ‘Investigating Inflation Persistence Across Monetary Regimes’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123:3, August 2008, 1005 - 1060

Benati, Luca and Charles Goodhart (2008), ‘Monetary Policy Regimes and Economic Performance: The Historical Record, 1979-2008’, prepared for B. Friedman and M. Woodford, editors, Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 1D, (to be published by North Holland in 2010)

Blinder, Alan S. Michael Ehrmann, Jakob de Haan, Marcel Fratzscher and David-Jan Jansen (2008), ‘Central Bank Communication and Monetary Policy: A Survey of Theory and Evidence’, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming

Cogley, Timothy W., Thomas J. Sargent (2002), ‘Evolving Post-WWII U.S. Inflation Dynamics’, in B. Bernanke and K. Rogoff, eds. (2002), NBER Macroeconomics Annuals 2001, Cambridge, The MIT Press.

Cogley, Timothy W., Thomas J. Sargent (2002), ‘Drifts and Volatilities: Monetary Policies and Outcomes in the Post WWII U.S.’, Review of Economic Dynamics, 8(April), 262-302

Gürkaynak, Refet S., Andrew Levin, and Eric Swanson (2006), ‘Does Inflation Targeting Anchor Long-Run Inflation Expectations? Evidence from Long-Term Bond Yields in the US, UK and Sweden’. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2006-09

Stock, James H., and Marw W. Watson (2007), ‘Why Has U.S. Inflation Become Harder to Forecast?’, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 39(1), 3-33

Figure 1 Inflation, and cross-sectional standard deviation of inflation rates in the euro area

(source: Benati and Goodhart, 2008)

Figure 2 Short-term nominal rates in the euro area

Figure 3 Standard deviations of annual CPI inflation and output growth since January 1999

(source: Benati and Goodhart, 2008)

-

[1] I am very grateful to Luca Benati for his valuable input.

-

[2] In the last panel of Figure 1 the cross-sectional standard deviation has been computed by excluding Slovenia, which until the second half of the 1990s exhibited an inflation rate in excess of 20 per cent (see the second panel), and can therefore be regarded as an outlier.

-

[3] See Benati (2008).

-

[4] These studies are surveyed by Blinder et al. (2008).

-

[5] Specifically, beyond the euro area we have considered all countries for which we could find at least seven years of data in the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics database.

Europska središnja banka

glavna uprava Odnosi s javnošću

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt na Majni, Njemačka

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukcija se dopušta uz navođenje izvora.

Kontaktni podatci za medije