Generation €uro – What Europe can do for you

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the ECB Youth Dialogue Event, Bocconi University, 13 March 2019

For many of you here today at Bocconi University, Europe has become a matter of course. Most of you have known no currency other than the euro. You do not remember a time when prices were in Italian lire, French francs or Deutsche Mark. Your monetary identity is closely linked to the European project of integration, unity and rejection of nationalism.

But years of crisis have led some people to challenge this idea of Europe. Critics of the European Union (EU) have been on the rise in recent years. Many of them see the EU as depriving nation states of their sovereignty and accelerating the seemingly destructive and unequal forces of globalisation.

In my remarks this evening, I will argue that the EU is more needed than ever for its more than 500 million citizens. But we need to work harder to ensure that young adults – many of whom face highly uncertain employment prospects – can reap the full benefits of a united Europe.

Achieving a more cohesive and stronger Europe requires everyone, including young people, to speak up and get involved in debates. I therefore strongly welcome initiatives such as European Generation here at Bocconi that provide a platform for discussion and critical thinking on EU policies. You are the ones who will chart the path that decides where the currents of history will take Europe next.

I am here tonight for this reason. I will start by presenting a few facts that highlight some of the challenges facing young people today, and what they could mean for cohesion in Europe. I will then present proposals for solutions that can help shape our discussion on what Europe can do for you.

Poorer than their parents

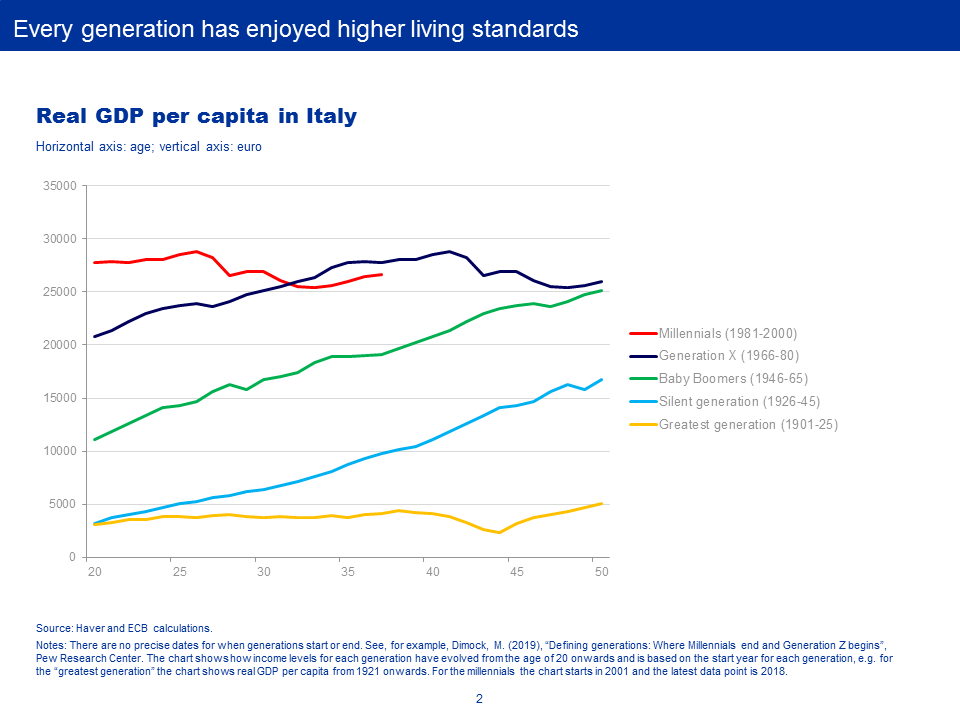

Since the beginning of the 20th century, every generation has enjoyed higher living standards than the one before. You can see this for Italy on my first slide, which shows the evolution of real GDP per capita – a crude proxy for prosperity – going back to what is called the “greatest generation”, part of which grew up during the Great Depression. The chart shows how income levels for each generation have evolved from the age of 20 onwards.[1]

Clearly, living standards have been increasing dramatically for every generation. This is not specific to Europe. But as this coincided with deeper European integration in the second half of the 20th century, rising living standards have contributed to the appeal of Europe and its widespread support.

The chart also suggests, however, that your generation – the millennials – is at risk of breaking with this trend.[2] More granular data make this point even clearer. You can see this on my next slide.

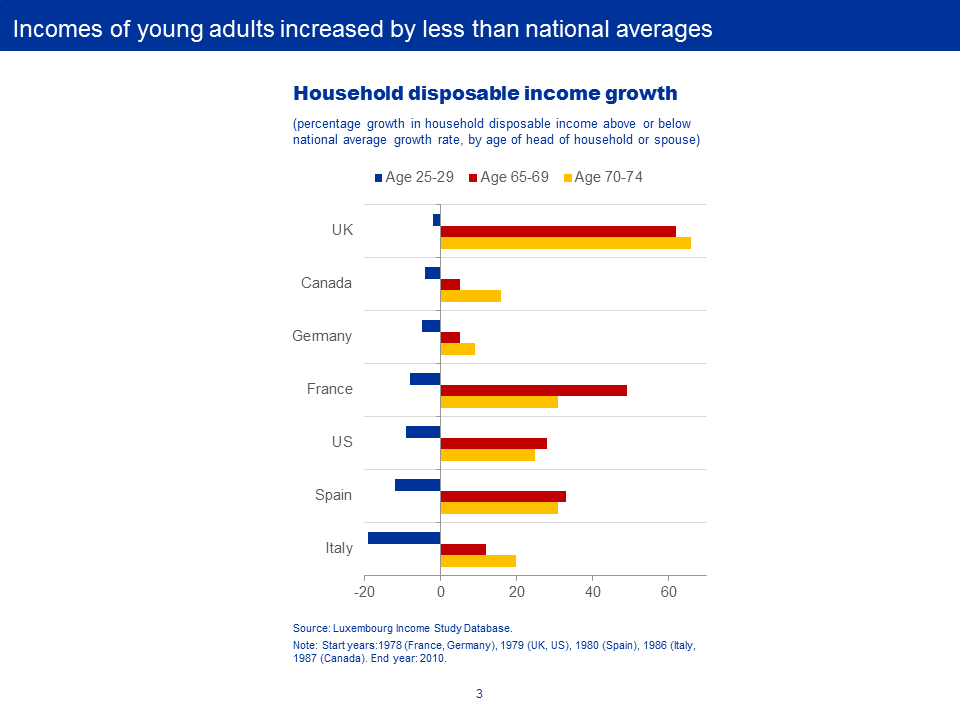

Around the globe, growth in total income that is available to a millennial household for spending or saving fell considerably behind national averages from the 1980s up to 2010. In Italy, disposable incomes of young adults increased by nearly 20% less than the national average from 1986 to 2010. Older generations, by contrast, have seen their relative incomes rise.

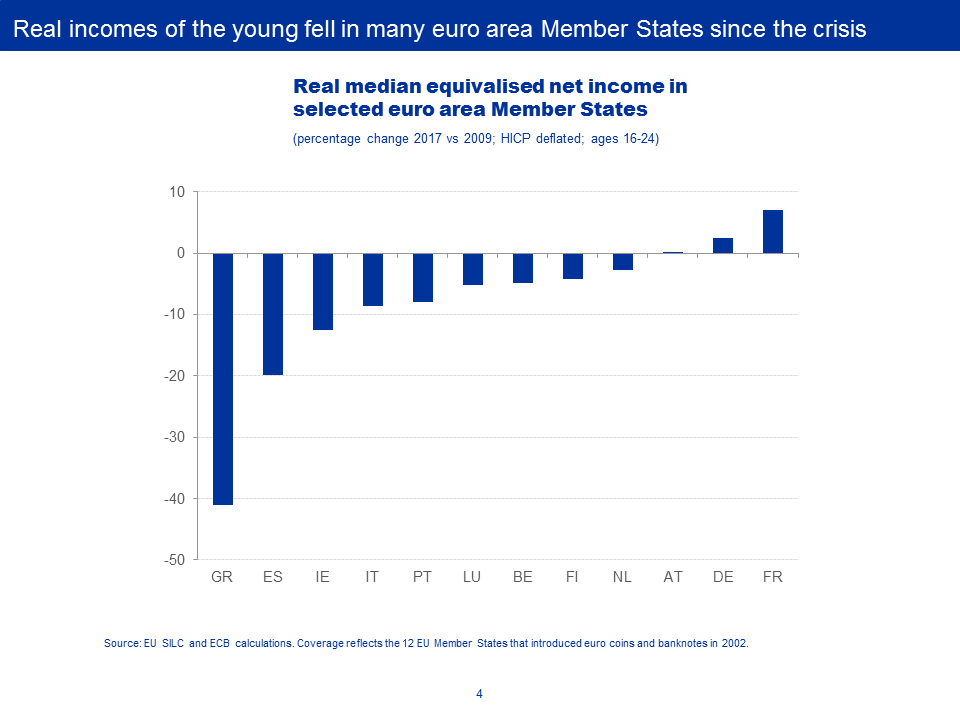

More worryingly, since 2009, real incomes of young households – that is, after accounting for the increase in consumer prices – have fallen, or have barely increased, in the majority of euro area countries.[3] You can see this on my next slide. In other words, the millennials could become the first generation not to enjoy higher incomes than previous generations. In some countries, the young have also suffered a steeper decline in net total wealth in recent years.[4] “Poorer than their parents” – this was the conclusion of a 2016 report by the McKinsey Global Institute.

For Europe, stagnating or falling incomes are not only an economic concern. Confusion about the causes and effects of these developments may also affect support for the EU and its institutions, and start a doom loop where mistrust against institutions would hamper their ability to act decisively to improve economic outcomes.

Surveys confirm that younger generations, who are growing up in an increasingly divisive political landscape and who are disgruntled by deteriorating social conditions, are more sceptical of the EU.[5]

The truth, of course, is that stagnating or falling incomes are the result of a wide range of factors, most of which are unrelated to EU or euro area membership.

Take unemployment, which has a particularly negative effect on household income, for obvious reasons. The deep recession after the financial and euro area debt crises, and the slow recovery thereafter, have undoubtedly been a major factor in stagnant household wage growth across generations.

Policies that stimulate consumption and investment have therefore been crucial in combating the cyclical effects of the crisis. Monetary policy has played an important role here. We have taken decisive and far-reaching action to stimulate the economy and to stop the fall in prices and wages. These policies have been highly effective.

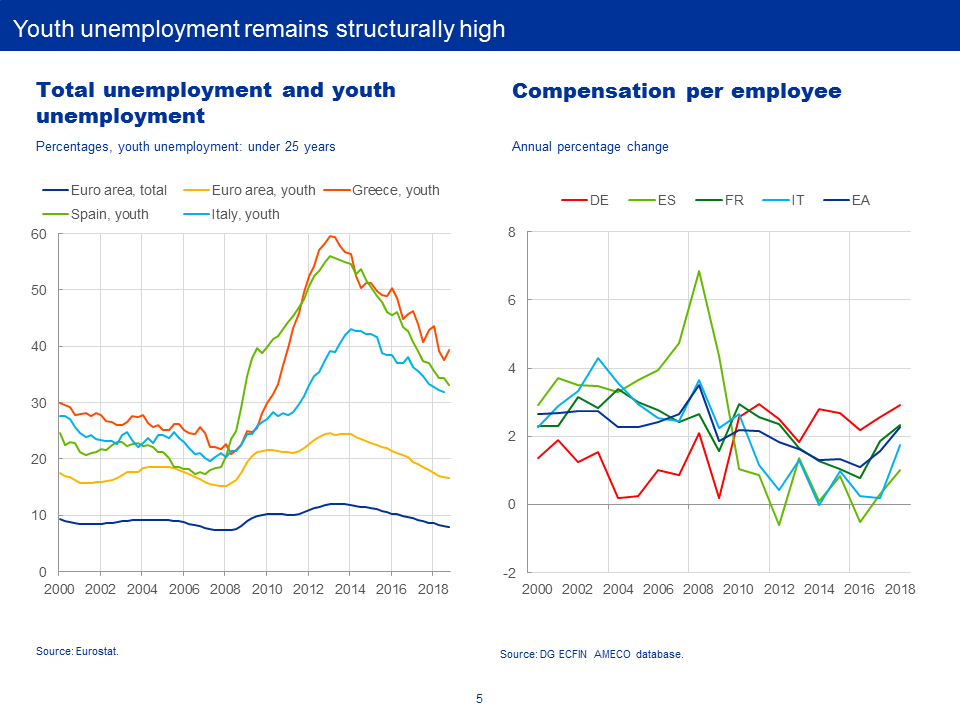

Since mid-2013, ten million people have found work in the euro area. As a result, the unemployment rate fell from around 12% in early 2014 to 7.8% in January this year, the lowest level in ten years. You can see this on the left-hand side of my next slide. Wages, too, are growing at their fastest pace in many years, thanks in large part to the effects of monetary policy. You can see this on the right-hand side.

But even so, youth unemployment remains twice as high as the total unemployment rate. You can see this on the left-hand side. Even before the crisis, nearly one in five people aged 15 to 24 was unemployed. In countries strongly affected by the crisis, youth unemployment remains intolerable, with rates above 30% in Italy and Spain and near 40% in the case of Greece.

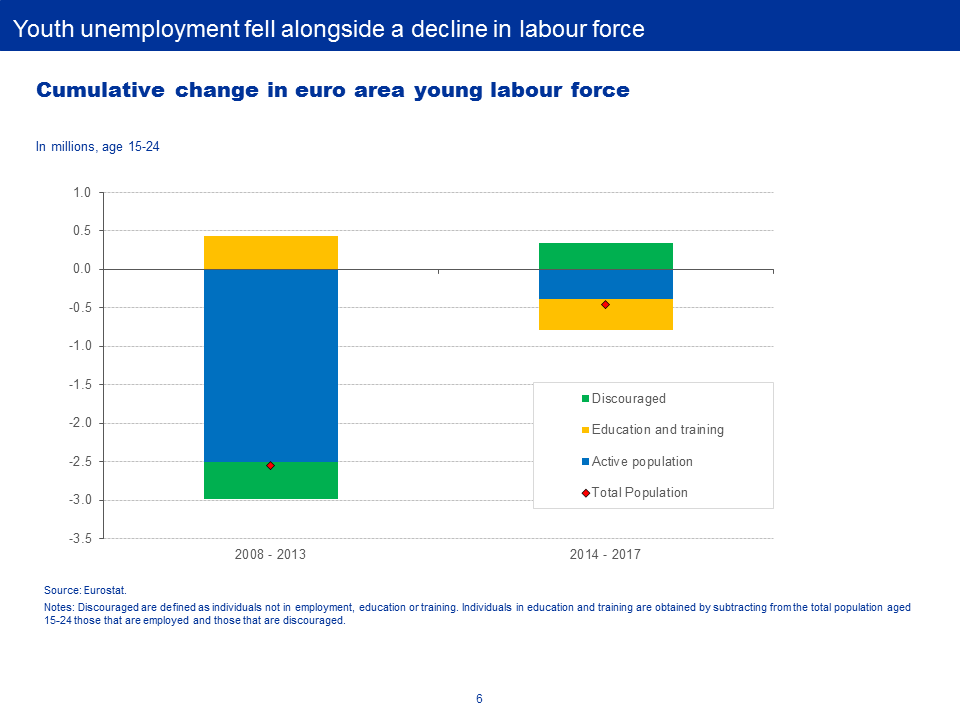

Strikingly, much of the fall in youth unemployment during the recovery reflected a shrinking young labour force, rather than strong employment growth.[6] You can see this on my next slide. This suggests that the sources of falling or stagnating household incomes of younger generations may be much more structural in nature.

Three such structural factors are worth pointing out.

The first relates to demographic changes. Our societies are ageing. The shrinking young labour force primarily reflects a fall in the percentage of the total population accounted for by young people.

The second factor relates to the impact of new technologies. Digitisation and robotisation are transforming our societies. Demand for high-skilled workers is accelerating and young people are responding by seeking higher education, thereby leaving the labour force. I will come back to this in a minute.

But it is telling that people who have completed tertiary education have accounted for more than 80% of total employment growth in the current recovery, up from 60% pre-crisis. And in the low-skilled sector, and increasingly also the medium-skilled sector, wages are increasingly being held back by technological progress and globalisation.[7]

The third structural factor that has contributed to flat or falling real household incomes of younger generations relates to national labour market institutions. Trade unions, for example, have gradually been losing significance over the past two decades or so.[8]

More so, atypical forms of employment have hit the younger generation particularly hard. In 2000, for example, the share of young people working part time was below 18%. It increased to more than 33% last year.[9] And more than one in four of those currently working part time do so involuntarily.

Also, young workers today are twice as likely to be in temporary work as older workers, a gap that has widened since the early 2000s.[10] And the share of young temporary workers in the euro area is also considerably larger than in other advanced economies. You can see this on my next slide. In the euro area, more than 50% of those aged 15 to 24 have temporary contracts, compared with less than 10% in the United States.

The upshot of these three factors is that using the EU as a scapegoat for economic malaise is far too easy, and often wrong.

Being part of the EU, the Single Market and the single currency is a strength, which contributes to creating jobs and offering young people opportunities to grow and develop.

Under the Erasmus programme, for example, 9 million young people have been able to study, train and gain professional experience outside their home countries.[11] More generally, research shows that EU membership boosts per capita incomes, on average, by approximately 10% in the first ten years after joining the EU.[12]

But all of this is to no avail if people don’t see it that way. The implications for Europe are therefore clear, and they can be summarised in two points.

The first is that if we want your generation to embrace the EU, it has to provide tangible benefits that you can clearly associate with it – in other words, it needs to build on output legitimacy.[13] The EU needs to make a more visible contribution to sharing the fruits of economic growth more broadly across generations.

The second is that Europe needs to pay more attention to those left behind – to those who need support in the face of a rapidly changing labour market.

Let me address these two points in turn.

Richer than their parents: improving the quality of education

Two broad measures are needed if the EU is to deliver on the first point – and make the European pie grow larger for younger generations: improve the quality of education and promote future technologies.

Significant progress has already been made in the field of education. The proportion of young people aged 15 to 24 in education rose by almost 5 percentage points between 2008 and 2017, reaching 57%.

But quantity is not quality. If young Europeans are to compete in a rapidly changing labour market, they must excel in basic skills. Yet many countries still have high proportions of underachievers in mathematics, reading and scientific literacy. In all three disciplines, one in five pupils is a low achiever.

A lack of basic skills reduces a young person’s chances of succeeding in the labour market and thereby also risks cementing prevailing inequalities of opportunity. Since the 1990s, social mobility has slowed across the OECD, meaning that those in lower income groups have less chance of moving up the ladder.[14] As a result, according to the OECD, it would take five generations for children from low-income Italian families to attain the level of mean earnings.

Despite this, public expenditure on education has been declining in recent years. For the EU as a whole, it fell from 4.9% of GDP in 2014 to 4.7% in 2016, the latest year for which data are available. Here in Italy, spending on education amounts to just 3.9% of GDP, compared with 6.9% in Denmark. Just 10% of total public expenditure is directed towards education in the EU.

We can do better. We need to step up our joint efforts to improve the quality of education in Europe.[15]

Few Member States have fiscal space allowing them to spend more, but all of them have the opportunity to spend better. Many have been recommended by the Commission to increase investment in education.[16] They need to follow up on these recommendations.

Maximising employment opportunities

Education, however important, is only one ingredient in enabling younger generations to thrive in the future. The second is to maximise employment opportunities.

Europe should become a leader, rather than a follower, in the fourth industrial revolution, which is evolving at breakneck speed. But today, European tech companies are lagging behind those in Silicon Valley or China. Data suggest that in the United States many more people are employed in high-tech sectors than in the EU.[17]

Yet, it is frustrating to see the EU’s spending on research and development (R&D) stagnate at around 2% of GDP for the past 20 years or so.[18] You can see this on my next slide.

Research shows that this shortfall in R&D intensity is not so much of a problem in industries where EU firms are well established.[19] It is more of an issue in industries where EU firms are underrepresented. The EU has most of its R&D in medium-tech sectors, which have, on average, lower R&D intensity rates.

In other words, we lack the sort of creative destruction which would help Europe move into new, higher-technology sectors. Take low-carbon industries as an example. Research shows that no EU firm has a competitive advantage in battery or photovoltaic technology, although these sectors are likely to be key drivers of future growth.[20]

A lack of entrepreneurship has a direct impact on productivity and pay. High-tech sectors are high-productivity sectors that pay higher wages. A recent study by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that the wage premium in US high-tech sectors is, on average, about 100% – that is, a person is likely to earn twice as much in a high-tech industry as they would in other industries.[21]

The EU has the ability to steer its course of action. We need to strengthen Europe’s capacity to innovate by mobilising public and private investment to support digitalisation in leading industries.[22] Reforms that facilitate the reallocation of capital and labour will be instrumental, both within borders and across borders. The capital market union is a case in point. And we can make sure that progress in digital technologies goes hand in hand with high data protection standards.

Fight against poverty: the role of the EU

My second point is that a changing labour market implies that, as always, there will be winners and losers. The benefits will not be shared equally.

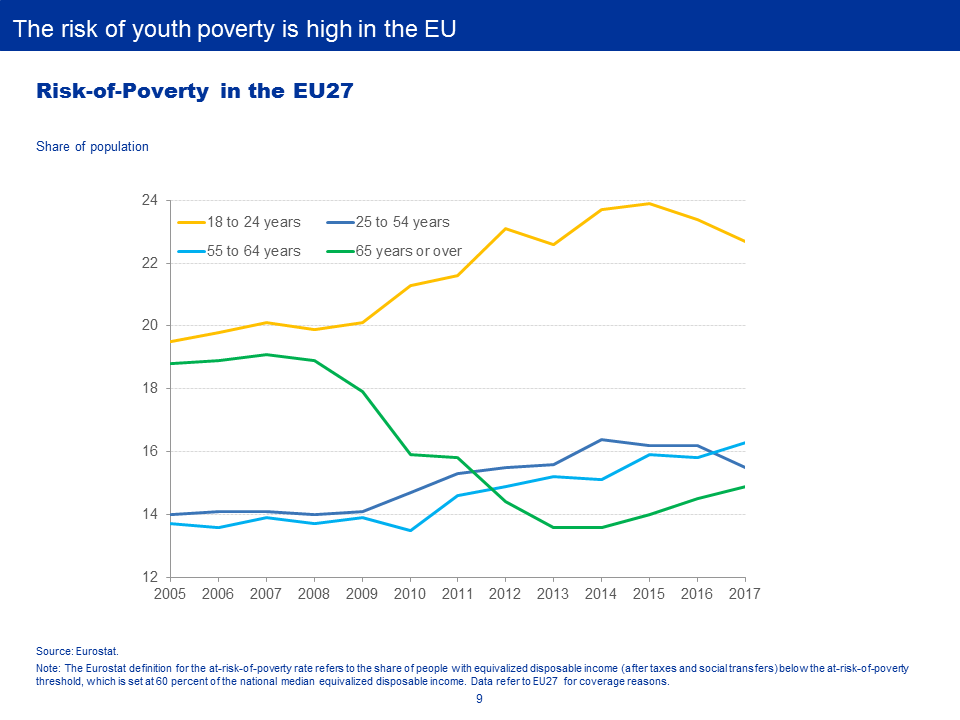

The social implications of high unemployment for young people are already concerning. As the young have suffered disproportionately from unemployment in the aftermath of the crisis, their risk of poverty has risen significantly. You can see this on my next slide. Today, young people are the cohort most likely to be poor – even in absolute terms.[23] “Poorer than their parents” turns out to be something of an understatement then.

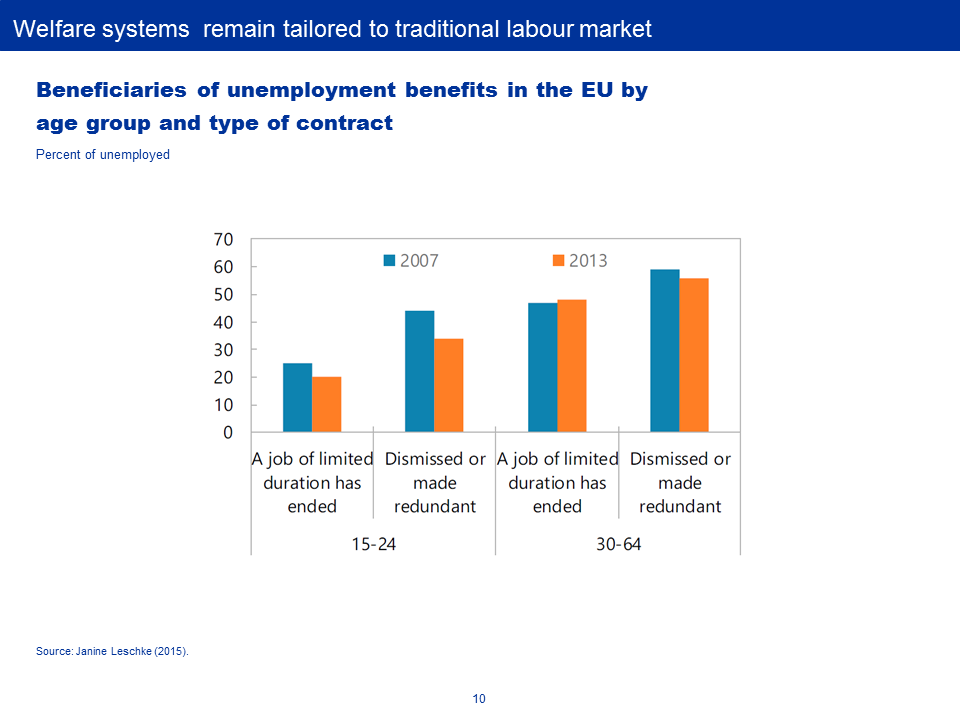

The rising risk of youth poverty also reflects the design of existing welfare systems, which remain tailored to traditional labour markets. For example, their larger share of temporary contracts makes the young more vulnerable to economic downturns than older workers. At the same time, the eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits remain largely based on factors that disproportionately benefit older workers, such as the duration of employment.

This risks leaving young people without access to social security benefits.[24] You can see this clearly on my last slide. There is a significant gap across generations when it comes to recipients of unemployment benefits in the EU.

Let me give two examples of how the EU can help.

First, EU policies to eliminate corporate tax avoidance can help protect national welfare systems that are being threatened by falling tax revenues.[25] Second, more direct EU funds could be made available for the fight against poverty.[26]

The EU’s youth guarantee, for example, has been a true success. Each year since 2014, more than 3.5 million young people have taken up an offer of employment, continued education, a traineeship or an apprenticeship. We can build on this success.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Many young Europeans entered the job market during one of the worst recessions in living memory. Many have seen their real incomes stagnate or fall. Not all young people have been affected in the same way, of course, but high youth unemployment, and deteriorating economic conditions more generally, are something that concern us all, not least because they affect social cohesion and could threaten to undermine the European project.

What we collectively make out of this experience will shape the future of Europe. It will determine whether the EU has succeeded in creating what its founding fathers had in mind: a genuine European identity, destined to leave the legacy of war and atrocities behind.

To achieve this, action is needed at national and at EU level. We need structural and fiscal policies to set the conditions for balanced and sustainable growth in sunny days, alongside with our monetary policy. And in rainy days we need a robust and accountable crisis management framework that avoids the devastating output and employment losses experienced after the financial and euro area crises.

We need to promote and attract private investment so that European companies can become leaders rather than followers in the fourth industrial revolution. And we need to make sure that young students receive the education they require to successfully compete in the global digital labour market, and to ensure that young workers, across the EU, are adequately protected in a more demanding labour market.

This is what Europe should do for you to help you fulfil your projects and your dreams.

The rest is in your hands.

Thank you.

- [1]Based on the start year for each generation, e.g. for the “greatest generation” the chart shows real GDP per capita from 1921 onwards.

- [2]Of course, the world is changing and millennials’ priorities may have changed all along. For example, younger people may attach less importance to pay than older generations.

- [3]The number of countries in which real incomes for prime-age workers (25-49) fell is notably lower.

- [4]In Italy, for example, mean net wealth of those up to 40 years fell by 40% between 2008 and 2016, while it fell by only 13% for those aged 65 and above. See Bank of Italy (2018), Survey on Italian Household Income and Wealth, 12 March.

- [5]Asked how they would vote in a referendum on EU membership, 63% of young millennials in education were in favour of staying in the EU. The intention to vote “remain” dropped to 44% percentage points when older unemployed millennials were asked. See “What Millennials Think about the Future of the EU and the Euro”, eupinions Policy Brief 2016/01.

- [6]See Qu, H. and Schölermann, H. (2018), “Youth Unemployment during the Euro Area Economic Recovery”, in IMF Country Report No. 18/224, Euro Area Policies, July.

- [7]See Chapter 3 of the April 2017 IMF World Economic Outlook.

- [8]For the impact on wages, see, for example, Kügler, A., Schönberg, U. and Schreiner, R. (2018), “Productivity Growth, Wage Growth and Unions”, paper presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking on “Price and wage-setting in advanced economies”, Sintra, Portugal, 18-20 June.

- [9]Ages 15 to 24. For prime-age workers (25-54), the share increased from 14.5% in 2000 to 20% in 2018Q3.

- [10]See European Commission (2017), Employment and Social Developments in Europe, Annual Review.

- [11]There are plans to improve the programme and increase its budget in the coming years. See https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4e5c3e1c-1f0b-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1.

- [12]See Campos, N., Coricelli, F., and Moretti, L. (2018), “Institutional integration and economic growth in Europe”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Article in Press. See also Baldwin, R., Francois, J. and Portes, R. (1997), “The costs and benefits of eastern enlargement: the impact on the EU and central Europe”, Economic Policy, Vol 12(24), pp. 125–176.

- [13]See also Anderson, C. and Reichert, M. (1995), “Economic Benefits and Support for Membership in the E.U.: A Cross-National Analysis”, Journal of Public Policy, Vol 15(3), pp. 231-249. The authors show that individuals living in countries that benefit more from EU membership display higher levels of support for their country’s participation in the EU.

- [14]“Low income” refers to the bottom earnings decile. See OECD (2018), “A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility”; and Boone, L. and Goujard, A. (2019), “France, inequality, and the social elevator”, VOX column, 4 March.

- [15]The EU, for its part, must work harder on allowing a broader recognition of academic degrees and professional qualifications. If we want to better match demand and supply in the Single Market, then we need to make it easier for workers to move across the EU. There is empirical evidence of a highly significant relationship between intra‐EU migration and the extent to which foreign degrees are recognised. Other nations understand the importance of skill transfer. China, for example, has signed agreements on the mutual recognition of higher education degrees with many EU Member States. See Capuano, S. and Migali, S. (2017), “The migration of professionals within the EU: Any barriers left?”, Review of International Economics, Vol. 25(4), pp. 760-773; and European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2018), “The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report”, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- [16]In 2018 alone, the European Commission identified ten countries in the EU with challenges to investment in the area of education, skills and lifelong learning. In addition to this, the country specific recommendations identified challenges to investment in six other countries.

- [17]It is not always possible to match international data classification standards. But by some estimates, the gap could be as large as six percentage points, with some 10% of employees working in high-tech sectors in the United States. See: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/htec_esms.htm and https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-5/pdf/the-high-tech-industry-what-is-it-and-why-it-matters-to-our-economic-future.pdf.

- [18]See Veugelers, R. and Batsaikhan, U. (2017), “European and global manufacturing: trends, challenges and the way ahead”, in Remaking Europe: The new manufacturing as an engine for growth, Bruegel Blueprint Series, Vol. XXVI.

- [19]See Veugelers and Batsaikhan (2017, op. cit.).

- [20]See Kalcik, R. and Zachmann, G. (2017), “Europe’s comparative advantage in low-carbon technology”, in Remaking Europe: The new manufacturing as an engine for growth, Bruegel Blueprint Series, Vol. XXVI.

- [21]See US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018), “High-tech industries: an analysis of employment, wages, and output”, Vol. 7, No 7, May.

- [22]See European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/priorities/digital-single-market_en

- [23]See IMF (2018), “Inequality and Poverty across Generations in the European Union”, IMF discussion note, January.

- [24]See also European Commission (2017, op. cit.).

- [25]See Cœuré, B. (2018), “Taking back control of globalisation: Sovereignty through European integration”, contribution to the 2018 Schuman Report on Europe, 28 March. The European Commission is already using competition tools to address possible tax arbitrage by multinational corporations, safe in the knowledge that no large company can threaten to leave the world’s largest market. The EU is also supporting efforts to revise international tax rules for digital companies.

- [26]With the adoption of the European pillar of social rights in 2017, the EU has recognised the challenges of a changing economy and the need to strengthen its social dimension to ensure inclusive welfare systems. See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf. Currently, the EU social budget accounts for only 0.3% of total public social expenditure in the EU. See European Commission (2017), “Reflection paper on the social dimension of Europe”, 26 April.

Európska centrálna banka

Generálne riaditeľstvo pre komunikáciu

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt nad Mohanom, Nemecko

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Šírenie je dovolené len s uvedením zdroja.

Kontakty pre médiá