- THE ECB BLOG

Learning from crises: our new framework for euro liquidity lines

29 January 2024

The ECB can lend euro to non-euro area central banks to reduce the risk of financial stress spilling over to the euro area. Piero Cipollone, Philip Lane and Isabel Schnabel explain how we have made such liquidity lines more effective and agile.

The financial disruptions during the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have once again underscored the importance of euro liquidity lines. The market tensions triggered by these crises squeezed euro liquidity in a significant number of non-euro area countries. In response, the ECB extended euro liquidity lines to the relevant central banks, thus enabling them to alleviate the funding strains on their domestic financial institutions. Providing euro liquidity to non-euro area countries shields the transmission of monetary policy in the euro area and minimises the risks of adverse feedback loops, making the euro area more resilient.

We recently adjusted our framework for the provision of euro liquidity through the ECB’s swap and repo operations to make these instruments as effective and agile as possible.[1] The framework retains the fundamental elements already in place, and integrates the existing repo facilities into a unified permanent framework called the Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP). These changes came into effect on 16 January 2024.

The changes to the framework reflect three key lessons from recent experiences. First, that the risks of negative effects on monetary policy transmission increase in the event of disorderly market conditions outside the euro area. Second, that the ECB must be able to react quickly to rapidly unfolding events. And third, that the mere existence of a liquidity line pre-empts financial tensions from materialising. The revised framework gives those countries with close economic and financial links to the euro area either standing or fixed-term renewable access to our liquidity lines in normal times. It also expands access to a broader set of countries in times of crisis or a heightened risk of crisis. At the same time, the role of liquidity lines as a “backstop” is reinforced with appropriate surcharges on lending rates. These surcharges help preserve incentives for non-euro area banks to first try to borrow from the private market before resorting to liquidity lines. They also limit the scope for unintended adverse side effects such as excessive foreign borrowing in euro.

Strong demand for euro liquidity lines during recent crises

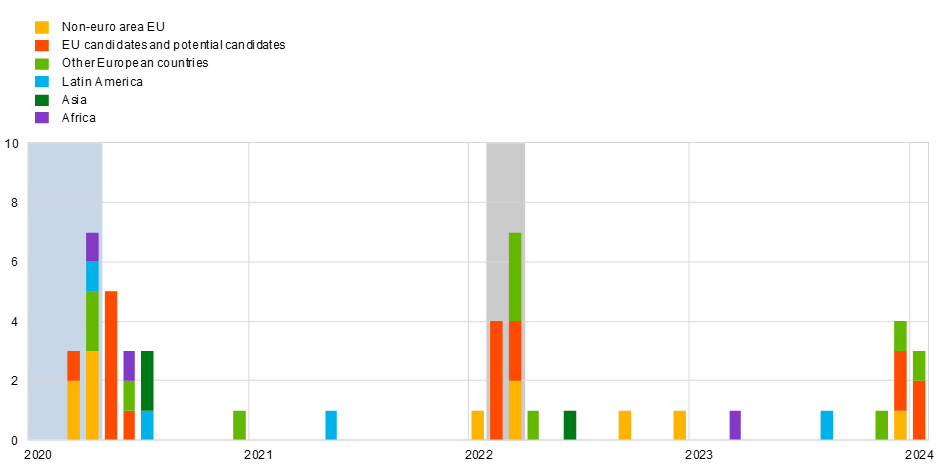

Amid financial market tensions during the initial phase of the pandemic, the ECB received a first wave of requests for liquidity lines within a relatively short period of time around March 2020. A second wave of requests reached the ECB after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. While most of these requests originated from non-euro area EU countries and EU candidate and potential candidate countries, several inquiries for euro liquidity also came from other European countries and other regions of the world (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Number of requests for ECB liquidity lines by region

Source: ECB

Notes: Requests include inquiries under the main framework and EUREP. The blue shaded area signals the onset of the pandemic, the grey shaded area the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As part of our response to these requests we set up a temporary repo facility, EUREP, which provided an additional precautionary backstop for central banks of countries that were not eligible under the then prevailing ECB framework, as we described in more detail in 2020. We subsequently prolonged the facility in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine and the resulting market tensions.

As the severe financial market tensions and high degree of uncertainty and contagion risk presented a clear monetary policy case, the Governing Council accommodated many of these requests. The ECB offered non-euro area central banks either swaps or repos, the latter under either the main framework or EUREP. With the choice of instrument, we took into account the need to protect the ECB’s balance sheet against financial risks. We only granted swaps in cases where those risks were limited or where it was useful for the ECB to have reciprocal access to the currency issued by the foreign central bank in question.

Chart 2

Usage of euro liquidity lines

Source: ECB.

Note: Outstanding amounts refer to the aggregate daily amount of euro-denominated liquidity provided across all central bank liquidity lines.

While use of the facilities has remained sporadic and for small amounts (Chart 2), this should not be taken as a sign that they are not needed. As the recent crises have shown, the mere existence of precautionary liquidity arrangements can have a calming effect. Empirical evidence suggests that the ECB’s liquidity lines have been effective in reducing financial pressures on euro funding markets.[2]

Our review of the existing framework confirmed that liquidity lines granted to non-euro area central banks are monetary policy instruments. They help to prevent impairments in the monetary policy transmission arising from heightened foreign euro demand or disruptions in cross-border wholesale funding. By providing euro liquidity, they also help the ECB fulfil its price stability objective, which remains the primary motivation for granting liquidity lines.

In addition, liquidity lines prevent euro liquidity shortages from morphing into financial stability risks. They provide a backstop source for borrowing in euro, which limits the scope for upward pressure on euro money market rates and removes the incentives for fire sales of euro-denominated securities by foreign investors.[3]

Finally, the ECB’s liquidity lines also have benefits for the pursuit of price stability by fostering the international use of the euro in global financial and commercial transactions. They enhance the transmission of monetary policy on a more structural basis, too, since a clear framework for liquidity lines signals the ECB’s willingness to provide a backstop if a crisis were to materialise.[4]

The new framework continues to acknowledge the risk that liquidity lines may affect incentives in ways that are undesirable from a euro area monetary policy perspective. In particular, if access to euro liquidity is perceived as easy, this may encourage unhedged currency exposures in the country receiving euro liquidity and heighten financial euroisation. It may also lower incentives for monetary authorities to maintain foreign exchange reserve safeguards and keep prudent financial regulations in place. This, in turn, could lead to more frequent crisis episodes in recipient countries.

This is why the new ECB framework maintains the features established to address these risks. First, liquidity lines are regularly reviewed and can be terminated if such risks were detected. Second, most of the temporary lines are established via repo agreements for which the non-euro area central bank needs to pledge high-quality euro-denominated collateral to ensure that the lines do not substitute prudent foreign reserve management. Third, the operational parameters of a euro liquidity line are set in a way that encourages a return to market-based arrangements. They foresee, among other things, a backstop rate at which euro liquidity is provided, which is close to the rate at which the ECB provides euro liquidity to its domestic counterparties. Such pricing encourages reliance on market funding since the use of the liquidity lines may be expensive. Our liquidity lines provide only short-term funding with a maximum tenor of a few months to ensure that they only address temporary liquidity needs. This encourages the return to market-based arrangements as soon as possible. Fourth, the pricing can be adjusted to discourage borrowing when it is not consistent with our monetary policy stance.

As before, liquidity lines must not be used for foreign exchange interventions but are meant as a means for foreign central banks to provide euro liquidity to their domestic financial institutions.

We continue to decide on liquidity lines, and the choice between swaps and repos, based on several factors: the requesting country’s systemic relevance, its economic, financial or institutional interconnectedness with the euro area, the strength of fundamentals and creditworthiness as well as any reciprocal need for foreign currency.[5]

Our case-by-case approach remains unchanged. The Governing Council assesses all requests individually, taking into account the monetary policy rationale and risks entailed.

What has changed?

The crisis experiences have shown the importance of an agile and flexible framework which the Governing Council can activate quickly in response to different kinds of shocks.

As before, the ECB can still extend swap and repo lines. What is new, however, is that all repo lines are now brought together in a permanent EUREP facility. This abolishes the distinction between the main framework and EUREP.

In normal times, only shocks in countries with sufficiently tight financial and economic links to the euro area have the potential to impair monetary policy transmission.

Indicators of such links are the size of a country’s economy, its level of euroisation and the financial and economic interconnectedness, including institutional linkages such as EU membership. To put this in perspective, the countries with a standing euro swap line account for 23.8% of global economic activity and 34.5% of the euro area’s total external trade.

In times of crisis, risks of adverse feedback loops increase. Typically, this happens through deteriorating investor sentiment vis-à-vis risky assets, an increased sensitivity to pre-existing vulnerabilities, or a destabilising repricing of euro area securities triggered by fire sales abroad.[6] This can impinge on euro area financial markets and, by impairing monetary policy transmission, on price stability.

This is why, building on the experience with the ad hoc EUREP facility during the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine, the new framework provides for access conditions to be broadened in times of crisis or when there is a heightened risk of a crisis materialising. This is when contagion and asset fire sales may have particularly strong adverse effects on euro area financing conditions, leading to deeper monetary policy implications.

Hence, in normal times, liquidity lines can only be extended if an economy is of systemic relevance to the euro area. But in times of crisis, liquidity lines can also be extended to countries that have limited individual systemic relevance. That may be the case if, amid disorderly market conditions, such smaller countries could together adversely affect monetary policy transmission. In view of heightened regional risks associated with the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East, we have applied this feature of the new framework to prolong the repo lines of several non-EU European countries until 31 January 2025.

The new streamlined framework also harmonises pricing and our risk control, in particular with regard to collateral eligibility requirements for repo lines. This will improve the efficiency of our decision-making.

Finally, we have also updated our communication policy. We will now disclose the full set of liquidity lines granted under the new framework as of 29 January 2024. The liquidity lines currently in place include eight swap arrangements with countries of major systemic relevance. Most of them take the form of reciprocal arrangements which also give the ECB access to the respective foreign currency. In addition, we have granted seven repo arrangements under EUREP.

Overall, the revised framework makes improvements in several areas, while maintaining its key features. These are summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Maintained features

| Adjusted features

|

Conclusion

ECB President Christine Lagarde has said recently that the world is going through “an age of shifts and breaks” in which it faces an unprecedented series of shocks.[7] Central banks play a crucial stabilising role in this situation, and euro liquidity lines are an important part of the ECB’s toolkit to protect monetary policy transmission and strengthen resilience against crises. We are confident that our new framework will live up to the challenges of international liquidity provision in an increasingly volatile world in which central banks need to contribute to stability in line with their mandates.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

Two basic types of financial instruments can be used to establish a liquidity line: swap agreements and repurchase agreements – often referred to as “repo agreements”. Under currency swap agreements between two central banks, the borrowing central bank obtains the currency of another in exchange for its own currency, which is provided as collateral. Both central banks agree to reverse the transaction and repay the borrowed currency, plus a contractually agreed interest rate, on a specified date. Under repurchase (repo) agreements, the borrowing central bank obtains foreign currency for a specified period, and at a contractually agreed interest rate, in exchange for financial assets denominated in that same foreign currency which serve as collateral for the lending central bank. Under its repo agreements, the ECB provides euro to non-euro area central banks and receives euro-denominated financial assets as collateral.

See Albrizio, S., Kataryniuk, I., Molina, L. and Schäfer, J. (2021), “ECB Euro Liquidity Lines”, Bank of Spain Working Paper, No 2125; and Beck, R., Ferrari, M. and Titzck, S. (2021), “The effectiveness of ECB currency liquidity lines”, The international role of the euro, ECB, pp. 50-52. For more extensive evidence on the effects of Federal Reserve System liquidity lines, see Choi, M., Goldberg, L., Lerman, R. and Ravazzolo, F. (2021), “The Fed’s Central Bank Swap Lines and FIMA Repo Facility”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No 983; and Goldberg, L. and Ravazzolo, F. (2021), “The Fed’s International Dollar Liquidity Facilities: New Evidence on Effects”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No 997.

Bahaj, S. and Reis, R. (2022), “Central Bank Swap Lines: Evidence on the Effects of the Lender of Last Resort”, Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 89, Issue 4, July, pp. 1654–1693.

The contribution of the ECB’s liquidity lines to the international role of the euro serves the ECB’s price stability objective in two key ways. First, it reduces sensitivity to shocks to the exchange rate. A greater use of the euro internationally means that a larger share of euro area imports is likely to be priced in euro. As exchange rate movements have no mechanical impact on the price of euro-denominated imports, they will have a smaller effect on euro area consumer prices in the short- to medium-term. Second, it amplifies the effectiveness of the ECB’s domestic monetary policy. An increased usage of the euro abroad tends to lead to larger outward monetary policy spillovers from the euro area, which in turn entails larger spillbacks on the euro area. This effect tends to amplify the effectiveness of domestic monetary policy. See Lodge, D., Pérez, J., Albrizio, S., Everett, M. De Bandt, O., Georgiadis, G., Ca’ Zorzi, M., Lastauskas, P., Carluccio, J., Parrága, S. and Carvalho, D. (2021), “The implications of globalisation for the ECB monetary policy strategy”, Occasional Paper Series, No 263, September.

Similar criteria have been used under the main framework, see ECB (2014), “Experience with Foreign Currency Liquidity-Providing Central Bank Swaps”, Monthly Bulletin, August.

See e.g. Ludwig, A. (2014) “A unified approach to investigate pure and wake-up-call contagion: Evidence from the Eurozone's first financial crisis”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 48, Part A, pp. 125-146.

See Lagarde, C. (2023), “Policymaking in an age of shifts and breaks”, speech at the annual Economic Policy Symposium “Structural Shifts in the Global Economy” organised by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, 25 August