Demographic trends, technological progress and economic growth in advanced economies

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, 66° Congresso Nazionale di Pediatria (66th National Paediatrics Congress), Rome, 22 October 2010

Introduction [1]

First of all, I would like to thank the Società Italiana di Pediatria for inviting me to participate in its Annual Meeting.

You are probably wondering what an economist is doing at a paediatricians’ meeting. To tell you the truth, I have been wondering about that too. Let me try to answer that question.

In brief, this will be my line of argument, based on nine points.

In a society characterised by limited demographic growth, technological progress is the main engine of economic growth.

The main instrument for developing technology is human capital.

The supply of skilled labour, which makes intensive use of human capital, is not keeping pace with the increase in demand, either in the United States or in Europe.

This explains why there is a strong correlation between the level of education and the probability of getting a well-paid job. Those who do not have access to education risk being marginalised and having a relatively low income.

Over the past 25 years, the supply of education has not increased in line with demand, and this has generated a worldwide “excess demand” for high-level education, increasing competition and costs. In other words, when it comes to gaining access to high-quality education, competition is now much fiercer than it was for the previous generation.

In advanced societies, the new generations are not prepared for the new competitive environment. Such preparation occurs during the early years of an individual’s life (according to some, during the first seven years), when the personality and the cognitive abilities are shaped.

Educational methods are largely responsible for this lag. The natural tendency to apply the methods inherited from the previous generation is insufficient in the context of excess demand for high-quality education.

It is not easy to change educational methods, in respect of those we experienced ourselves, and to adapt them to the needs of a global society. It requires critical capacity and the ability to listen, powers which not many people have.

But there is one important exception, to which I will return at the end of my remarks.

I would like to develop each of these points in turn.

Main drivers of growth: theory

According to economic theory, growth is driven by developments in labour and capital and by developments in their productivity. Demographic trends affect economic growth via the effects related to the size and the structure of the population, i.e. mainly via changes in the number of persons of working age (usually assumed to be between the ages of 15 and 64). In turn, technological progress affects growth via the impact on labour and capital productivity.

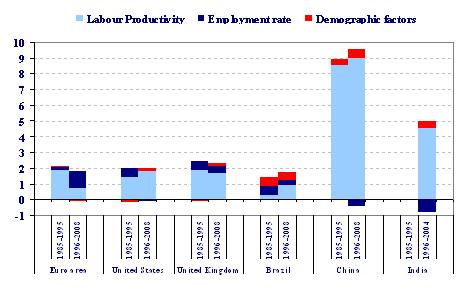

From a more analytical perspective, per capita income can be broken down into labour productivity (per person employed), demographic factors (i.e. the size of the working age population relative to the overall population) and the employment rate (Chart 1). If we compare some advanced economies, namely the euro area, the United States and the United Kingdom, and three emerging market economies, i.e. Brazil, China and India, three main messages emerge. First, productivity gains are the prime engine of economic growth. Second, productivity growth significantly slowed in the euro area after the mid-1990s, while it accelerated elsewhere (except in the United Kingdom), particularly in emerging economies. Third, demographic developments made a sizeable contribution to growth in the emerging market economies, while this contribution was much smaller or even negative in advanced economies. In essence, these data show that fostering innovation is key, especially for those economies characterised by a shrinking share of working age population owing to ageing. This leads me to a brief analysis of some stylised facts on demographic developments in advanced and emerging market economies. I will then talk about technological progress. Finally, I will discuss the importance of human capital accumulation and of education in particular.

Some stylised facts on demographic developments…

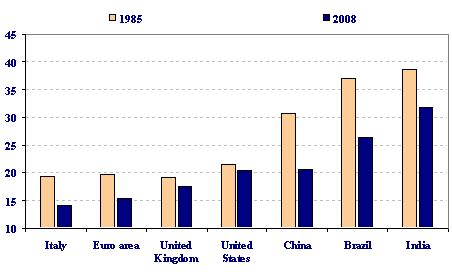

If we look at demographic developments in advanced economies such as Italy, the euro area (as an average), the United Kingdom and the United States and compare them with those in selected emerging market economies such as Brazil, China and India, three significant differences emerge.

First, emerging market economies tend to have more young people (Chart 2). In India almost one in three people were aged 14 or younger in 2008, while in Italy – which is among the countries with the lowest share of young people – the corresponding figure was only one in seven (14.2% of the overall population). The slide also shows that the share of people aged 14 or younger has been declining in all these advanced and emerging market economies since 1985. However, although this decline has been even stronger in the emerging market economies, these countries still have proportionately more young people.

Second, the share of the working age population in advanced economies has remained either broadly stable or has declined over the past 25 years, while it has risen substantially in emerging market economies (Chart 3). In Brazil, for example, the share of the working age population rose by more than 8 percentage points between 1985 and 2008, while it declined by almost 1.7 percentage points in Italy.

Third, the populations of many industrialised countries have been ageing, while those of Brazil, China and India have been getting younger.

These diverse demographic developments – and the ageing of the population in particular – make it more difficult for many advanced economies to continue to grow and to remain competitive on world markets. The problem has been exacerbated over the past 25 years, not least because many advanced economies have not acted quickly enough to address the ageing problem and its detrimental impact on economic growth. But competition from emerging market economies has not waited. Moreover, in many of these emerging economies, competitiveness has also been stimulated by investment in the technology sector. Let me elaborate on this last point with the help of a few figures.

…and on technological progress

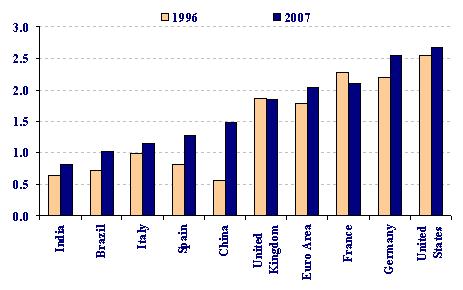

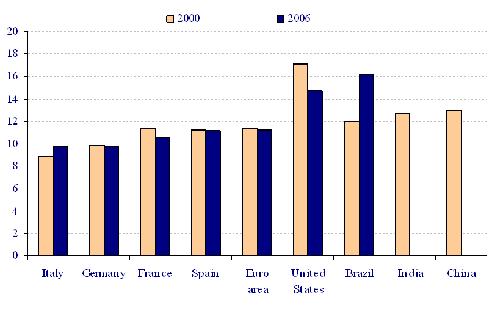

Ten years ago the EU Member States committed to transforming the EU by 2010 into “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world […]”, as emphasised in the Lisbon strategy. In order to achieve this aim, an explicit target was introduced whereby each country was to spend at least 3% of GDP on research and development (R&D) by the year 2010. The data clearly show that progress in this direction has in fact been very limited (Chart 4). Among the largest four euro area countries, Italy ranks the lowest, and its level of R&D intensity has increased marginally since 1996. [2] At the other end of the spectrum, China more than doubled its investment in R&D over the same period.

The role of human capital

Together with R&D, the economy’s ability to innovate crucially depends on human capital. [3]

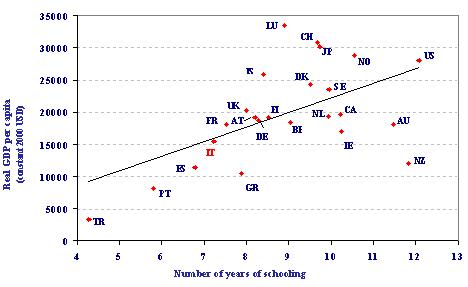

Human capital is a broad concept, covering a set of skills which are acquired through education, as well as via on-the-job training and experience. Also, human capital is affected by health conditions, on which people’s cognitive abilities directly depend. The importance of human capital to economic growth has been demonstrated in a number of empirical analyses. [4] Several studies show that more affluent economies are also richer in human capital. For example, there is a clear positive relationship between the average years of schooling and per capita income in advanced economies (Chart 5).

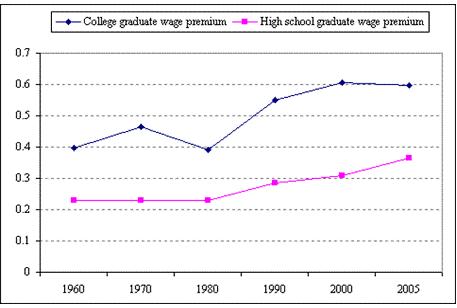

In addition, a vast literature in the field of labour economics has provided evidence that a positive causal relationship – which is significant and robust – can be found between the years of formal schooling (at primary, secondary and tertiary level) and wages. This evidence suggests that private, or so-called “Mincerian” [5], returns on education are within an average range of 6.5% to 9%; this means that an additional year of formal schooling is associated with a 7.5% increase in wages on average over a working life. [6] Chart 6 illustrates the evolution of the wage premium of college graduates and high school graduates in the United States. It shows that those who achieve higher educational levels enjoy substantially higher earnings; moreover, the wage gap between educated and less educated workers seems to have significantly widened since the early 1980s.

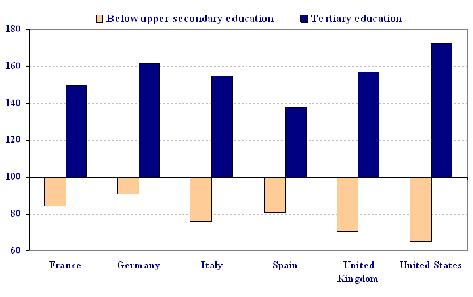

The evidence related to the rise in returns on education – together with that on the inequality of earnings – provides useful information on the supply and demand of skills. In particular, these factors would suggest that while the relative demand for more educated workers has steadily increased in line with technological advances, the supply of highly skilled labour has not always kept pace with demand. In other words, the rise in the premium associated with technical skills indicates a mismatch between the insufficient supply of education and growing labour market requirements. This hypothesis – which has recently been put forward by Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz in respect of the United States [7] – would in my view also apply to a number of European economies where high-quality education is in short supply. An analysis of educational wage differentials in selected EU countries reveals that Germany and Italy register the highest premium for those with tertiary education, indicating high excess demand for highly educated workers (Chart 7).

Educational attainment in the United States and selected EU countries. Where do we stand?

Chart 8 shows the percentage of the population which in 2008 had completed at least upper secondary education (left panel) and tertiary education (right panel). Both panels show the educational level of the young generation (aged 25-34) versus older age groups (therefore those who were in the young cohort a generation earlier). All countries have experienced an overall improvement in the skill levels of their population: on average 79% of euro area citizens aged between 25 and 34 have at least completed upper secondary education; this proportion is 26 percentage points higher than among those aged between 55 and 64. However, there are considerable disparities across countries. For instance, in Spain and Italy the percentage of young people with upper secondary education is still below the euro area average, and much lower than in Germany and France (which are now at levels close to the United States). When looking at tertiary education, the performance of the Italian economy is significantly worse.

In addition, the quality of education is at least as important as the number of years of formal schooling. This is usually measured by a number of indicators, including pupil-to- teacher ratios, the educational level of teachers, and students’ performance in internationally standardised tests. Interestingly, a number of international studies suggest that, with regard to explaining the impact of education on growth, the quality of schooling is more important than the quantity. Put simply, it is not only the time spent at school that matters; it is what you learn, how you learn it, and from whom. More generally, recent research conducted by economists at the ECB suggests that improvements in the quality of labour have made a substantial positive contribution to labour productivity growth in the euro area. In particular, those who have achieved at least degree-level education are, on average, more productive than those who have only primary education. [8]

Overall, despite the progress made, improving education – in both quantitative and qualitative terms – remains high on the policy agenda in Europe. In order to give you a sense of the relative importance assigned to education in advanced and emerging economies, Chart 9 illustrates the expenditure in education as a share of total government expenditure. Again, the Italian economy’s bottom ranking is striking – especially in comparison with emerging economies – and thereby calls for a more decisive effort in this area.

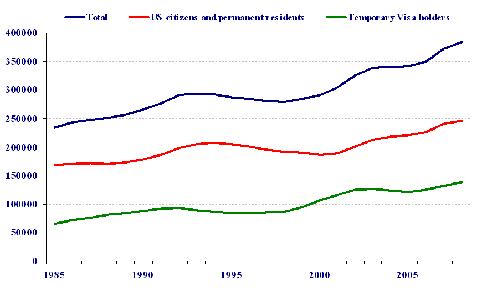

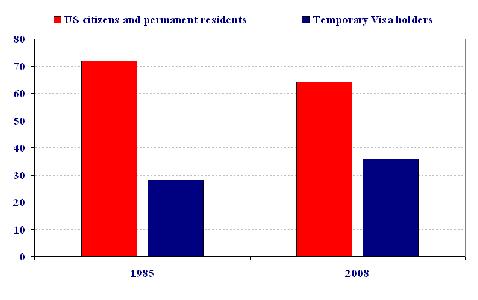

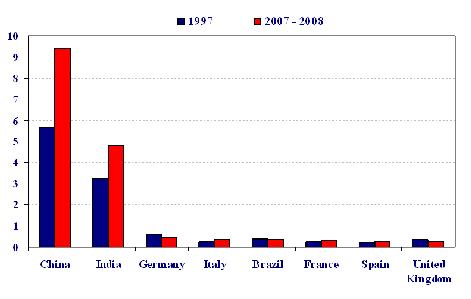

Finally, let me add that today’s young people in advanced economies face much tougher competition than those three decades ago; in particular, competition for access to top international universities appears to have increased. The total number of students in science and engineering has been steadily increasing since the mid-1980s, and the rise has been most rapid over the past decade (Chart 10). Looking at the breakdown between US and non-US citizens, we can see that in 1985 fewer than 30% of science and engineering students came from outside the United States, whereas in 2008 their share was close to 40% (Chart 11). A breakdown of doctorate students in the United States by country of origin reveals that the share of Chinese and Indian students has increased at an extraordinary rate, from 9% in 1997 to almost 15% in 2007-08 (Chart 12). Over the same period, the proportion of students from EU countries remained substantially below the proportion of Chinese and Indian students, and has changed only marginally, despite the increasing need in advanced economies for highly skilled labour.

Concluding remarks

In industrialised countries, the generation now entering the labour market is, for the first time since the Second World War, facing worse conditions, on average, than those faced by the previous generation. And there is a risk that the situation will be even worse for the subsequent generation. If there is not a rapid reversal of this trend, our societies may face huge economic and social problems.

Reversing the trend will require decisive action at the level of both supply and demand of education. Public debate has largely focused on supply, which is certainly important and assigns responsibility for improving the quality of education to public authorities. But too little attention is paid to demand, which is insufficient owing to a lack of awareness of the fact that, without an adequate education, an individual’s standard of living not only will not improve, but will inevitably decline. Our societies are not sufficiently aware of the fact that those who are not adequately prepared to compete for a better education will be denied access.

Acquiring human capital is not just essential, it is becoming increasingly difficult and expensive. We are thus faced with the problem of how to prepare the young people of today, and future generations, for the challenges that lie ahead. In order to resolve this problem, there must be a greater understanding of learning processes. Jean Piaget, the pioneer of the constructivist theory of knowledge, explained that learning progresses through the stages of sensory and motor skills and cognitive abilities, before resulting in an ability to assimilate formal instruction. A deficiency at any one stage can result in problems in the stages thereafter. Without the appropriately developed cognitive skills, even intensive academic instruction and hours of private tuition do not succeed in making up for the gap accumulated in the previous learning stages. A child’s first years are his or her most formative ones. From birth, children are filtering stimuli and learning how to interact with their surroundings and the people they are in contact with. Parents play a critical role in laying the foundations for their child’s education. They are most often a child’s first teachers: they pass on not only the fundamentals of education, but also teach the child how to learn.

However, when educating their children, parents often rely on personal experience. But the simple transmission of knowledge from parents to children is no longer sufficient. Piaget wrote that “indeed, the aim of intellectual education is not to know how to repeat or to conserve ready-made truths. It is in learning to gain the truth by oneself at the risk of losing time and of going through all the roundabout ways that are inherent in real activity”. He continued: “Education, for most people, means trying to lead the child to resemble the typical adult of his society…but for me and no one else, education means making creators...You have to make inventors, innovators – not conformists”. [9]

Parents must receive guidance on how to correctly adapt the education of their children to the new needs of society in the future. However, parents are often unwilling to accept outside interference. They will not be inclined to listen to anyone who tries to convince them that simply reproducing the systems and procedures that they themselves experienced – which, as I explained earlier, were probably sufficient in a world that differed from the one we are living in today, with an excess demand for high-quality education – is damaging for the cognitive growth of their children.

There is, however, one exception to this. Personal experience tells me that if there is someone that parents are prepared to listen to, someone in whom they place absolute faith, it is the paediatrician. I don’t want to go into why this is, but it is a fact, a fact which you paediatricians have to take on board and which gives you considerable responsibility. On the other hand, the arguments that I have put forward up to now are well-known to you, as you will have experienced them yourselves during your education. The difficulty of gaining access to higher education, the growing competition and the correlation between education and quality of life are not new to you. Whether you like it or not, your role cannot be limited to the field of medicine because your actions have an impact on the development of economic systems. Through your scientific work and your practice, you contribute every day to extending life and thus to the ageing of the population. The problem is that our advanced societies are not yet well-equipped to deal with these developments. Those who pay the highest price may well be precisely those children that you help every day, who will not be adequately prepared to face the challenges that society has dropped on them.

What, then, is the function of the paediatrician? My suggestion to you is to take advantage of the receptive ears that parents have for you, not only to give them the necessary medical advice, but also to help them to be parents in our modern society, a role which is much more important – and more difficult – than is often thought.

I am sure that you are already doing so.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Charts

| Chart 1: Average contribution to real per capita GDP growthGrowth rates, in % |

|

| Source: ECB computation on World Bank, WDI database. |

| Chart 2: Trends in youth populationPercentage of population aged 14 years and below |

|

| Source: World Bank. |

| Chart 3: Trends in working age populationPercentage of population aged between 15 and 64 |

|

| Source: World Bank. |

| Chart 4: Developments in R&D expenditurePublic expenditure on R&D as % of GDP |

|

| Source: World Bank.Note: For Italy and Brazil the latest available data point is 2006. |

| Chart 5: Human capital and economic growth |

|

| Sources: Barro-Lee (2010); World Bank, WDI database. |

| Chart 6: Growing wage premium to high skilled labour and wage differential in the US |

|

| Sources: Goldin and Katz (2007).Note: “College graduate wage premium” is based on the college / high school wage differential (in logs). “High school graduate wage premium” is based on the high school / eighth grade wage differential (in logs). |

| Chart 7: Relative earnings from employment, by level of educational attainment for 25-64 year-olds, 2007 |

|

| Source: OECD.Note: upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education = 100. Data for Italy refer to 2006 (latest available year) |

| Chart 8: Level of education |

|

| Source: OECD. |

| Chart 9: Public spending on educationTotal public spending on education as % of government expenditure |

|

| Source: World Bank. |

| Chart 10: Full-time graduate students in science and engineering in the US (I) |

|

| Source: National Science Foundation. |

| Chart 11: Full-time graduate students in science and engineering in the US (II)% of total graduates |

|

| Source: National Science Foundation. |

| Chart 12: Countries of origin of non-US citizens earning PhDs at US colleges and universities% of total doctorates awarded |

|

| Source: National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. |

-

[1]I would like to thank Roberta Serafini, Isabel Vansteenkiste and Nadine Leiner for their drafting suggestions. I would also like to thank Ioannis Grintzalis for his valuable research assistance. The views expressed reflect my personal opinions.

-

[2]The latest data available for Italy are for 2006.

-

[3]Benhabib, J. and Spiegel, M. (1994), “The Role of Human Capital in Economic Development”, Journal of Monetary Economics.

-

[4]For general surveys of the contribution of human capital and education to economic growth, see Krueger and Lindahl (2001) and Wasmer et al. (2006). De la Fuente and Ciccone (2002) review the literature with specific reference to Europe.

-

[5]The “Mincerian equation” (developed by Polish-American economist Jacob Mincer) specifies a relationship between an individual’s education and experience and his or her wages. See Mincer (1974), Schooling, experience, and earnings, National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

[6]Innovative methodological approaches have been employed in the field of labour economics (such as studies of twins who followed different education and life paths) to establish causality between education and private returns. For an extensive review of the micro evidence, see Card, D. (1999), “The causal effect of education on earnings”, Handbook of Labor Economics.

-

[7]Goldin, C. and Katz, L. (2007), The race between education and technology: the evolution of US educational wage differentials, 1980 to 2005, National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

[8]See Schwerdt and Turunen (2007), “Growth in euro area labour quality”, Working Paper Series, No 575, ECB.

-

[9]Piaget, J. (1972), Problèmes de psychologie génétique, Denoël/Gonthier, Paris.

Banca Centrală Europeană

Direcția generală comunicare

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt pe Main, Germania

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproducerea informațiilor este permisă numai cu indicarea sursei.

Contacte media