ECON Committee Hearing on “Improving the economic governance and stability framework of the Union, in particular in the euro area”

Intervention by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, Brussels, 15 September 2010

Dear Madam Chair,

Dear Members of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,

I would like to thank you for this opportunity to exchange views on an issue which is both topical and highly relevant. It’s topical because in a few weeks the Commission will publish its legislative proposals and Mr Van Rompuy will present in one month the report of the Task Force to the European Council. It’s highly relevant since the recent developments have demonstrated the urgent necessity of improving the economic governance and stability framework of the Union, in particular in the euro area.

Indeed, to improve the governance and stability framework of the euro area, we need to first understand what went wrong with the previous system and the risks that may occur if these failures are not remedied. There is now broad agreement on what went wrong. The system was not able to impose the discipline which is necessary in a monetary union. In particular, the mechanisms designed to promote budgetary discipline did not work as expected. First, the decision-making process underlying the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) did not prevent excessive deficits from emerging and, when they did, it did not correct them quickly enough. Second, financial markets did not act as deterrent against the accumulation of excessive deficits, as they did not discriminate between national issuers. As a result, a combination of the global financial and economic crisis – the worst since WWII – and the accumulation of undue imbalances within the euro area, resulting from insufficient attention being paid to relative competitiveness and inappropriate fiscal policies, created a severe debt burden for several countries.

Euro area countries cannot use the monetary instrument to inflate away their debt, so the deterioration of public finances has brought to the surface a series of issues which were not fully considered at the start of EMU. The first is that countries may have problems servicing their debt. This was not thought relevant because the SGP was supposed to prevent it occurring. The second issue is that financial markets may rapidly change their assessment of a country’s solvency, and actually trigger such an event. The fact that money can be gained from the bankruptcy of a company, or even a country, without ever investing in it, raises issues related to the functioning of financial markets which unfortunately have not been tackled – it seems to me – in recent reforms. [1] The third problem is that a sovereign default can have systemic consequences in a monetary union as a result of the financial interconnections. This explains why the risks affecting a relatively small part of the euro area in the course of last spring have had such significant effects on the euro.

This third dimension is still not fully understood, although it is one of the most important in view of the changes to be made to the institutional structure of the euro area. The interconnections created by the single currency have transformed what appeared to be a relatively limited problem affecting the Greek economy, which represents less than 3% of the area GDP, into a systemic issue. This explains why, as markets started to doubt the solvency of Greece, the speculative positions aimed at minimising losses or maximising the profits associated with such an event also affected the valuation of other sovereign assets and of the euro itself.

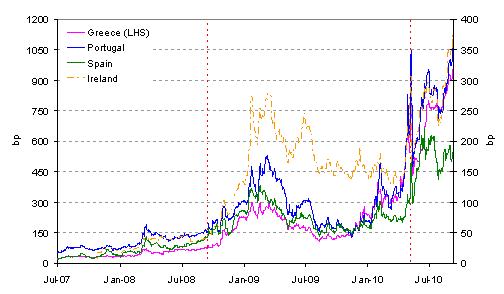

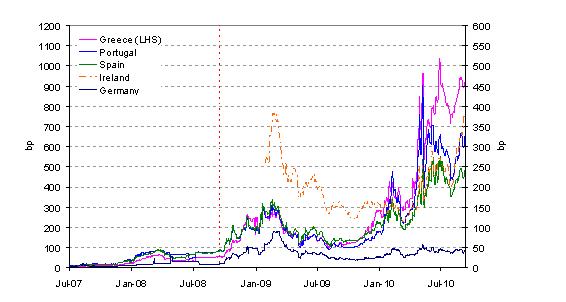

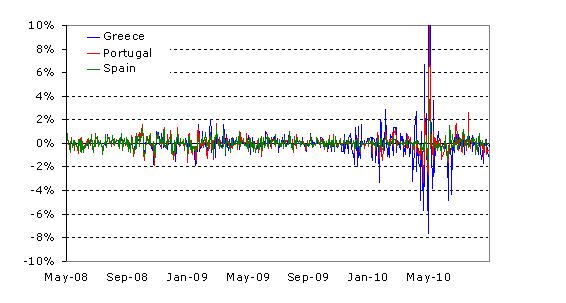

Tensions in the euro area financial markets mounted significantly in early May, reaching unusually high levels in some segments, higher even than after the failure of Lehman Brothers. Just to quote a few figures, between mid-February, right after the first European Council meeting on Greece, and Friday 7 May, the spread between the 10-year Greek and German government bonds increased by about 650 basis points. At the same time, the spreads for the Irish, Portuguese and Spanish government bonds also went up, by around 150, 230 and 90 basis points, respectively (see chart 1). Similarly, premia on credit default swaps (CDSs), a proxy for sovereign risk, also increased substantially. Interestingly, the CDS premium on German government bonds (i.e. the price to insure against their default – whatever that means!) increased to close to 60 basis points (see chart 2). Additional evidence regarding government bond dysfunctions is reflected by the daily changes in their prices: as shown in chart 3 this measure of uncertainty peaked in May 2010.

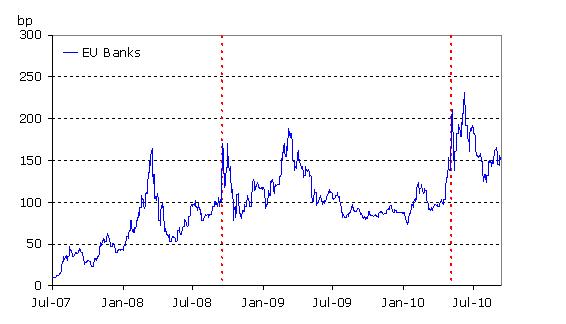

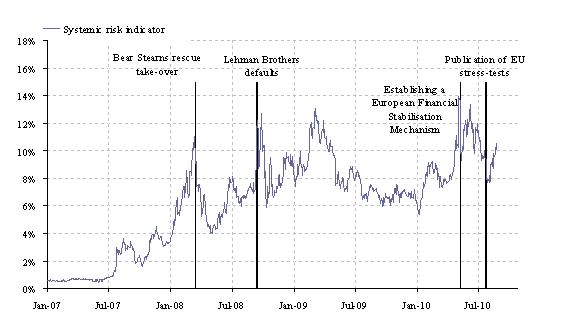

Tensions spilled over into market segments other than government bonds. Not surprisingly, the credit risk of the EU banking system mounted to levels higher than those observed after the collapse of Lehman Brothers (see chart 4). By the same token, the probability of a simultaneous default of two or more large and complex euro area banking groups, as measured by the indicator of systemic risk reported in chart 5, rose sharply on 7 May.

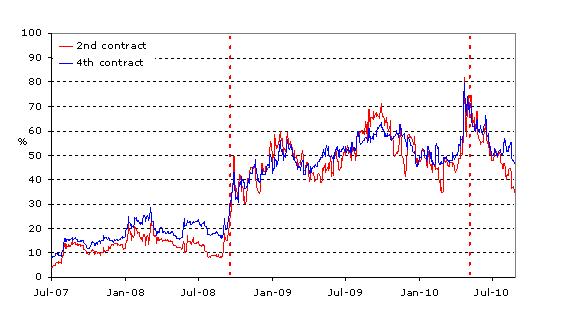

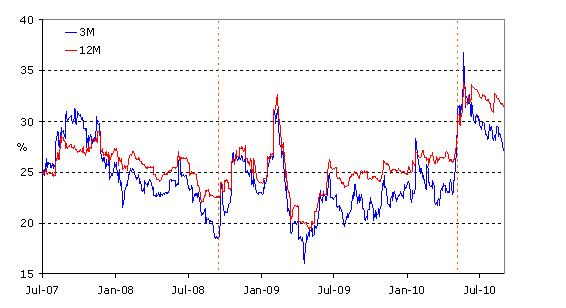

Money market volatility also surged (see chart 6): implied volatility on three-month interest rate futures went up in early May for contracts expiring six months (second contract) and 12 months (fourth contract) ahead.

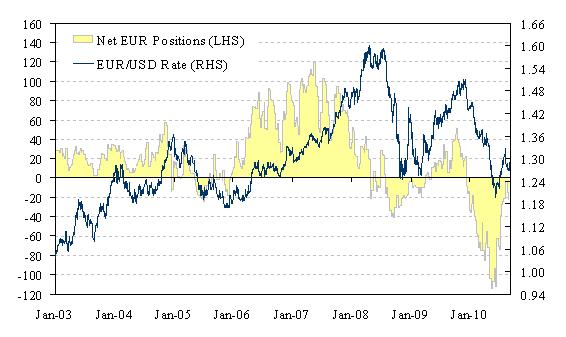

Regarding the foreign exchange markets, between mid-February and 7 May, the euro depreciated by 7% against the dollar, from USD 1.36 to 1.27 per euro. Shorting the euro became the proxy speculative position for selling Greek and other ‘peripheral’ debt. In early May the net short speculative (non-commercial) position against the euro reached a record 114,000 contracts, equivalent to about €14 billion (see chart 7).

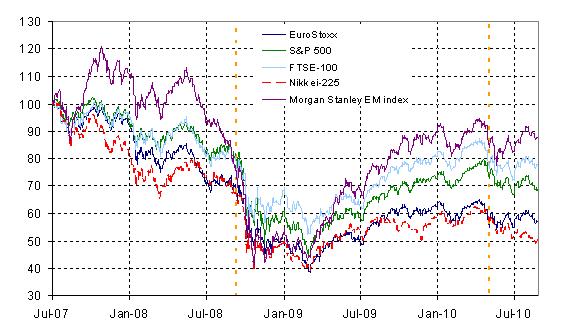

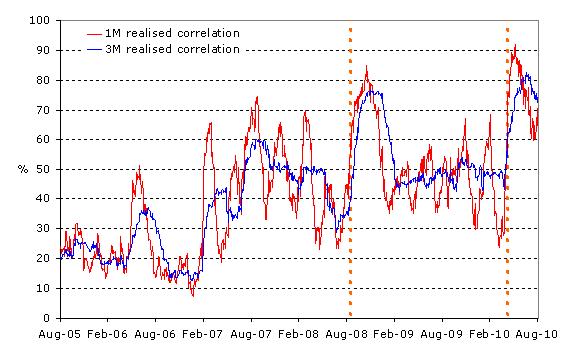

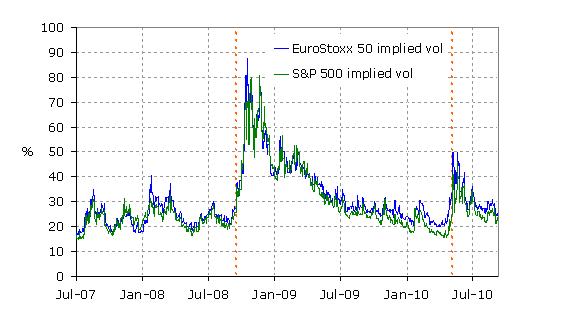

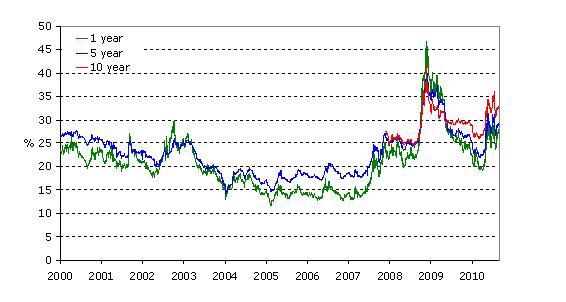

The turmoil had an impact on equity markets as well: between mid-February and 7 May, the euro area stock market declined by more than 7% (and by 15.5% from April 15 to May 7!). Even more worrisome, in May equity indices decreased worldwide (see chart 8). In May and June the average pair-wise realised correlation between S&P500 stocks went up more than it did after the Lehman bankruptcy. Loosely speaking, this indicates that concerns about macroeconomic developments had inhibited investors from differentiating between different stocks, and panic was mounting (see chart 9). Stock markets also became more volatile, as reflected by the increase in the implied volatility of the EuroStoxx50 and S&P500 indices, albeit at levels lower than those observed towards the end of 2008 (see chart 10). The long-term implied volatility of the US stock market also surged (see chart 11).

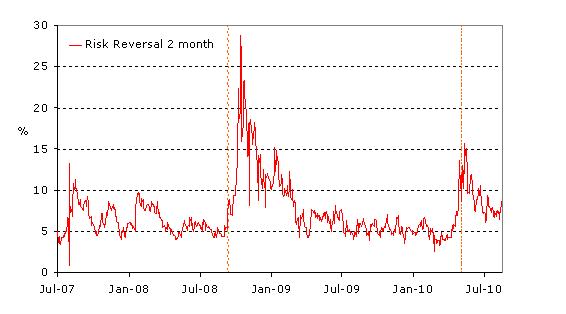

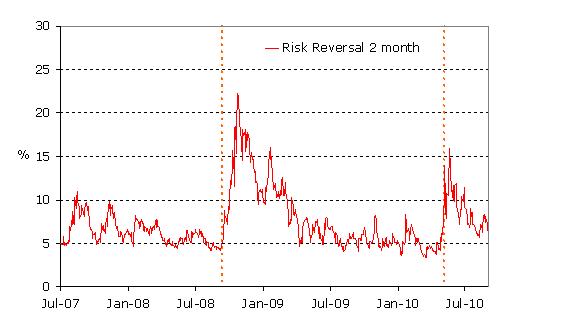

Finally, indicators of investors’ sentiment, as measured by the difference between equity put and call options implied volatilities, went up in May (see charts 12, 13, and 14).

All in all, on the eve of the first week-end of May the global financial system was on the verge of a meltdown similar to, if not worse than, the one which occurred after the failure of Lehman Brothers. Markets would indeed have collapsed if the Heads of State and Government of the euro area had not agreed – that weekend – to establish a European Financial Stability Fund to support countries in difficulty and if the ECB had not decided to intervene directly in some securities markets to restore their proper functioning. That action stopped the speculative rout and forced market participants that had taken short positions against the euro and some sovereign assets to bear losses. The actions succeeded in preserving the integrity of the euro area.

It would be a mistake to think that the risks which emerged last spring will never occur again. Unless the weaknesses that were exposed during the spring are definitely addressed, new bouts of instability may arise. The Van Rompuy task force has the mandate to produce concrete proposals. Those proposals must close all the loopholes in the institutional construction of the euro, which could leave it exposed to future attacks. This is the real challenge we are confronted with.

Any change in the institutional structure of the euro should start by avoiding the same simplifying assumptions made in the past. Let me mention three.

The first is to think that markets are always right and are able to discipline countries and their debts. Markets made mistakes in the past in under-pricing risk, they are probably doing so again now in over-pricing it, and they will also make mistakes in the future. Leaving to markets the task of disciplining budgetary policies and inducing the Member States to take corrective actions is an illusion that only economists can have. If we really want to prevent and correct imbalances, in particular fiscal imbalances, we need stronger institutional mechanisms, across the euro area and within countries. This means more rules and automatic sanctions.

The second mistake is to think that crises can be prevented altogether. Crises have occurred in the past and might occur in the future, also because of contagion. We have to be prepared for them and be able to manage them efficiently.

The third mistake is to think that there are easy, or ‘orderly’ solutions to crises. Crises are messy, contagious and have unintended consequences.

The ECB has developed concrete proposals to address the above issues. They are now well known, so let me be concise and point to the three main aspects, which relate to fiscal discipline, macroeconomic surveillance and crisis management. Let me start with two general, but important points.

The first is that these proposals do not change the fundamental nature of the euro area, in particular with respect to the basic allocation of responsibilities in relation to budgetary policy, which remains in the hands of the national authorities. There is no need to have a single budgetary policy in the euro area. No need for a so-called transfer union. However, national budgetary policies have to be conducted in a framework which is consistent with a single currency. We need a leap forward in the governance underlying the economic policies conducted in the member states of the euro area. We should therefore concentrate our efforts on strengthening discipline first and foremost in euro area countries since they share the common currency, making use of the provisions of the Treaty – notably Article 136 – which has been inserted into the Treaty precisely because the member countries of monetary union require enhanced economic governance. Whatever is decided for the euro area could conceivably also apply to the rest of the Union, but the discussion among all 27 Member States should not water down what is necessary for the euro area.

The second point is that the institutional framework can be strengthened within the current Treaty, exploiting to the extent possible secondary legislation. There is no need for a Treaty change to achieve the large part of proposals which are required and that we have put forward. There is also no time. As I mentioned previously, the doubts raised by financial markets about the ability of the system to become more resilient need to be answered quickly. If these answers are linked to a long and uncertain ratification process, doubts will spread again.

Let me now turn to the discussions which have taken place so far on the three main building blocs of the reform.

On the subject of reinforced fiscal governance, a first step forward was made on 7 September, when the ECOFIN Council endorsed the new framework of the EU Semester as had been proposed by the Commission in its Communication of 12 May. Better fiscal governance requires changes both at the national and European level. At the national level, the ECB supports the establishment of national fiscal frameworks that set out minimum requirements for compliance with EU fiscal and statistical rules and that in particular would promote more independence in the national fiscal assessment, high-quality standards, a medium-term orientation and an effective coverage of all general government finances. At the EU level, the ECB favours a strengthening of the fiscal framework around the five following measures:

more streamlined and hence more effective procedures in the assessment of fiscal developments;

reversal of the burden of proof, making it more difficult for the Council to overturn in its decisions the assessment of the Commission.

more independence in the collection, verification and assessment of the fiscal data and fiscal analysis at the level of the Commission.

more emphasis on public debt developments, as the Treaty foresees.

quasi-automaticity of sanctions in case of breaches of the rules, including the provision of both so-called procedural and financial sanctions.

The Commission’s Communications of 12 May and 30 June does not go far enough in the ECB’s view on two counts:

They thus far remain silent on how the independence of the fiscal assessment and the independence and quality assessment of the statistical data collection can be made more effective within the Commission. In particular, we would like to see some of the procedures currently in force in DG Competition at the level of the technical assessment and the role of the Commissioner in the college also being applied for DG ECFIN and its Commissioner. As regards statistics, the new Council Regulation of July 2010 should be followed up with deeds; in particular with more resources devoted to fiscal data and its verification by Eurostat.

The Commission ideas currently on the table provide too little in terms of streamlining the procedures and hence making them more effective. We have seen many times in the past that procedures are too lengthy and laborious before effective action can be undertaken to incentivise or enforce on Member States a correction in their fiscal developments. So far, procedures have been launched only on the basis of the notification by the Member States. It could be envisaged to also launch them on the basis of an assessment or a forward looking assessment by the Commission. Had this been done in the case of Greece, many problems could have been avoided or at least reduced.

On the second building block - broader macroeconomic surveillance - we see a strong need for making a quantum leap, given the large spillovers from the macroeconomic policies of one country on all other participating countries in the single currency area. Accordingly, the ECB proposes the creation of an alert mechanism based on a clear and limited set of indicators that identifies unsustainable policies at a sufficiently early stage. We would also like to see put in place a procedure for the correction of macroeconomic imbalances with a preventive and a corrective arm which includes graduated enforcement steps to ensure compliance, including sanctions. Again, the Commission ideas voiced in its communication of 30 June go in the right direction but are not yet ambitious enough to meet the long-term requirements of an efficiently functioning monetary union. We are awaiting for the new proposals in this field and stand ready to contribute actively.

Let me now spend a few words on the third building block, crisis management. There is a theory according to which if you have a good prevention system there will be no crisis. It is a theory, indeed. In practice, crises do occur, even though the institutional system underlying surveillance and prevention should be strengthened to avoid such crises. As I mentioned earlier, it would not only be a mistake but also irresponsible to assume that crises will never occur again. This would encourage market participants to speculate on their re-occurrence because of a lack of proper management framework. As we have experienced, self-fulfilling expectations could by themselves precipitate a crisis.

The creation of the EFSF ultimately averted the financial collapse in early May. Without such a system the euro would be vulnerable to any speculative attack against any of its members, be it justified or not by economic fundamentals. [2] The question is how to create a management mechanism that avoids crises without creating moral hazard. This is not a new issue. It has been dealt with in the context of the IMF and consists of attaching strong conditions, in terms of structural and fiscal policies, to any financial support that is provided to a country in difficulty. Financial support is disbursed only according to precise milestones, linked to compliance with the conditions contained in the programme. There is no need for Europe to reinvent the wheel. We can learn from the experience of the IMF. History shows that countries are not particularly keen to get financial support from the IMF, precisely because of its tough conditions.

The proposals put forward by the ECB go very much in that direction and aim to create a framework that can manage a crisis effectively while discouraging speculative attacks against the system.

The crisis management framework raises another issue, which is more complex and deserves some reflection. The issue is known as ‘private sector involvement’ in crisis resolution. What it means is that public money should not be used to bail out private sector organisations that have taken the wrong decisions. This would be the case if the money provided by the crisis management framework were used to reimburse the private sector for its losses, eliminating all the risks it was exposed to.

This issue was considered in the context of the IMF reform after the Asian crisis. The discussion showed that it is very difficult to design a simple mechanism which would make restructuring mandatory. The reason is simple. The solvency of a state is a different concept from that of a company or a financial institution. It ultimately depends on the economic and political sustainability of achieving and sustaining a given level of primary budget surplus to stabilise and reduce the debt. If a country commits to a certain recovery programme which justifies the financial support of the other partners, it cannot be considered insolvent and unable to reimburse its debts. Why should it in such cases restructure them? On the other hand, if debt restructuring is made too easy, or too ‘orderly’ – to use a fashionable term – market participants may consider it the easy way out for countries and might be tempted to take speculative positions from which they would profit in case of default. In other words, a restructuring mechanism, if too simple, could lead to moral hazard. Furthermore, the very nature of the markets would mean contagion spreading immediately to the other countries, as participants would start guessing which other country might need to undergo restructuring.

To sum up, using the words of a recent IMF document, in today’s advanced economies default is UUU, “Unnecessary, Undesirable and Unlikely”. [3] It is naïve to think that there is such a thing as an orderly debt restructuring mechanism.

What is the solution then, if we want to avoid moral hazard and unduly bailing out the private sector? The best way to involve the private sector is to ensure that a country which experiences financial difficulties implements a credible adjustment programme, which convinces markets to invest again in that country. Experience shows that successful programmes – with ‘success’ being measured by the policies which have been implemented – have ultimately made it possible to regain market confidence. It may take some time, and some re-profiling of official financial support, but in the end access to markets was regained.

If some form of rescheduling or re-profiling of the debt over time turns out to be necessary, for the debt to be sustainable, this can be achieved in an orderly way only through an agreement between creditors and debtors. Other forms of constrained action, on the creditor or on the debtor side, are bound to lead to litigations and produce disorderly effects on financial markets. In this respect, the adoption of collective action clauses by the euro area member states would make it easier for creditors and debtors to agree on a fair burden-sharing. This was the conclusion of the discussions in the context of the IMF and can be further explored at European level.

Another way to prevent market participants from being bailed out is to use the funds made available from the official support mechanism to purchase debt on the secondary market, at the prevailing market discount, rather than reimbursing the maturing debt at the nominal value. In this way holders of debt instruments willing to sell would have to accept the market haircut. This possibility is envisaged in the ECB’s proposals.

To conclude, the European Union is a community of law, subscribed to by the Member States in which pacta sunt servanda. This refers to all the pacts, starting from fiscal discipline in the member states to the commitment of the Member States to pay their debts. In my view, we have to be very careful in considering exemptions, such as providing the possibility for countries to unilaterally modifying the value of their debt contracts. The euro, and its underlying institutional construction, is about respect for the law. If any changes are to be made, they should be to strengthen these principles rather than to provide exemptions – dangerous exemptions which could undermine the stability and cohesion of the whole Union.

Thank you for your attention.

Chart 1: Tensions in euro area

Selected intra-euro area spreads against Germany (10Y)

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 2: Tensions in euro area

Selected government credit default swaps (5Y)

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 3: Dysfunction in the bond markets

Daily change in bond prices; in percent

Source: Bloomberg. Note: on 10 May, change in bond prices rose to +35% for Greece and +14% for Portugal.

Chart 4: Credit risk of EU banking system

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 5: Indicator of systemic risk in the euro area financial sector

Source: Bloomberg. ECB calculations

Chart 6: Volatility on interest rate futures

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 7: Non commercial euro positions

Source: Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)

Chart 8: Equity market development

Index price since July 2007, based on100 on 1 July 2007

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 9: Correlations between US equities

Average pair-wise realised correlation between S&P 500 stocks

Source: Citi Group

Chart 10: Volatility on equity markets

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 11: Long-term volatility of US stock markets

Implied volatility of long-term options

Source: Citi Group

Chart 12: Concerns about US stock market (1)

Difference between S&P 500 put and call options implied volatility

Source: Bloomberg; ECB calculations

Chart 13: Concerns about US stock market (2)

Difference between S&P 500 put and call options implied volatility

Source: Citi Group

Chart 14: Concerns about euro area stock market

Difference between EuroStoxx 50 put and call options implied volatility

Source: Bloomberg; ECB calculations

-

[1]L. Bini Smaghi, “Lessons of the crisis: Ethics, Markets, Democracy”, Milan, 13 May 2010 (http://www.ecb.int/press/key/date/2010/html/sp100513.en.html).

-

[2] “An Economist Reflects: A View from 2020: The Eurozone Break-up of 2013” Morgan Stanley Research Europe, 30 July 2010.

-

[3]Cottarelli, Forni, Gottschalk and Mauro, “Default in Today’s Advanced Economies: Unnecessary, Undesirable, and Unlikely”, IMF Staff Position Note 10/12, 1 September 2010.

Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα

Γενική Διεύθυνση Επικοινωνίας

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Η αναπαραγωγή επιτρέπεται εφόσον γίνεται αναφορά στην πηγή.

Εκπρόσωποι Τύπου