Basel III finalisation in the EU: the key elements and how they make the EU banking system more resilient

Published as part of the Macroprudential Bulletin 23, December 2023

The Basel Framework and Basel III

The Basel Framework, of which Basel III is the latest version, is a set of international regulatory standards for banks.[1] The standards are set by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) for internationally active banks. The members of the BCBS are central banks and supervisory authorities from 28 countries around the world. Members meet regularly to cooperate on the regulation and supervision of systemically important banks.

BCBS members agree to implement the standards and apply them to the internationally active banks in their jurisdictions. Although the framework is not legally binding, its implementation is monitored by the BCBS through its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP). Both the timeliness and the faithfulness of the implementation are evaluated and the materiality of any deviations from the Basel Framework is assessed.[2]

The latest changes to the framework, as set out in Basel III, seek to address the gaps and shortcomings in the previous framework which were exposed in the global financial crisis of 2007-09. The aim of Basel III is to create a more resilient banking system and the EU, including the ECB, has contributed actively to its development.

Currently, many jurisdictions are in the process of implementing the final elements of Basel III. To provide time for banks to adjust to the new standards and for jurisdictions to legally implement the revised framework, Basel III has been phased in over a number of years. While many parts of the framework have already been implemented and are applicable today, some key elements are yet to be put in place.

Final key elements in Basel III

The Basel Framework requires banks to meet risk-based capital ratios and the final elements of Basel III focus largely on the definition of banks’ risk-weighted assets (RWAs). The fact that banks are obliged to meet risk-based capital ratios means they need to hold a certain amount of regulatory capital against their RWAs, often expressed as:

The final elements of Basel III focus largely on defining the RWAs (the denominator in the equation above).

The key features which are now being implemented are as follows:

- Changes apply in the standardised approach to determining RWAs, using parameters which are clearly defined and calibrated in the capital rules.[3]

- Changes have also been made to the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach (notably the introduction of input floors on the parameters), allowing banks themselves to estimate the parameters used in the calculation of RWAs.[4]

- The option to use the IRB approach has been removed for certain types of exposure.

- Basel III introduces the output floor, which is a measure that sets a lower limit (floor) on the RWAs (output) calculated by banks using their internal models. It has been agreed that if the output floor is fully implemented the RWAs computed using internal models cannot fall below 72.5% of the RWAs computed using the standardised approach.

- Basel III also introduces a new operational risk framework, which refers to the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems, or from external events.

Basel III and resilience

The final Basel III reforms, in addition to the measures already implemented, will further increase the resilience of banks and the banking system. Several analytical reports provide evidence of the benefits of Basel III, one notable finding being that the long-term benefits clearly outweigh the costs. The BCBS evaluated the impact of the Basel III reforms[5] and found that they have already increased the overall resilience of the banking sector. [6] Market-based systemic risk measures have also improved, implying that not only the banks but also the system have become more resilient. The report also notes that higher resilience did not come at the expense of banks’ cost of capital. Similarly, the European Banking Authority (EBA) conducted a macroeconomic impact assessment of the final Basel III framework and concluded that its longer-run benefits will be substantial.[7]

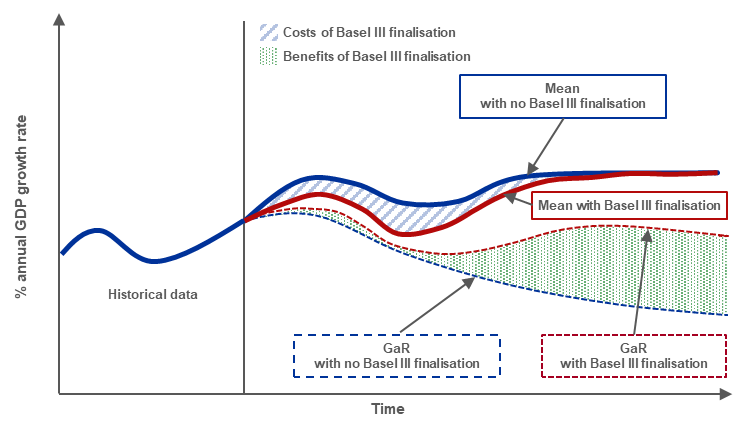

Macroeconomic impact analysis by ECB staff confirms that Basel III reforms have long-run benefits which outweigh economic costs in the transition period.[8] As illustrated in Figure A, the transitory costs of the reforms are outweighed by the long-term benefits. The new rules will benefit long-term bank solvency and profitability and will ensure that banks are better able to absorb losses in adverse economic conditions. Thus, there will be a permanent long-run increase in economic resilience.

Figure A

Stylised illustration of a cost-benefit assessment based on growth-at-risk

Source: Budnik, K. et al. (2021), “Macroeconomic impact of Basel III finalisation on the euro area”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 14, ECB, 26 July.

EU implementation of Basel III – state of play

Implementation is lagging behind the timetable agreed in Basel, according to which the reforms were to be phased in over five years starting from 1 January 2023.[9] In the EU, the co-legislators reached political agreement on Basel III implementation on 27 June 2023, the aim being to swiftly finalise the legal texts so that the new rules can apply as of 1 January 2025. Although this is two years behind the BCBS timetable, it is still broadly aligned with progress in other large jurisdictions. For example, the UK Prudential Regulation Authority published a consultation paper on the final Basel III reforms in November 2022. It is now expected that the final elements of Basel III will be applicable as of 1 July 2025 in the United Kingdom.[10] In July 2023, the US federal banking agencies published their proposal on how they intend to implement the outstanding Basel III elements in the United States, with the aim of ensuring they would be applicable as of 1 July 2025.[11]

The proposed EU laws implementing Basel III also envisage some deviations from the Basel Framework. For example, an existing deviation in the calculation of the credit valuation adjustment, which is the price assumed for hedging the counterparty credit risk of a derivative instrument, was not removed in the Credit Requirements Regulation (CRR3). Neither were already existing specific adjustments for small and medium-sized enterprises and infrastructure lending. In addition, transitional arrangements were introduced for the output floor, allowing banks to apply reduced risk weights for exposures to real estate and unrated corporates when determining RWAs under the standardised approach, making the output floor less binding during these years. It is foreseen that these transitional arrangements will be in place until 2032.

The EBA estimates suggest that the EU implementation will mean a capital increase 3.6 percentage points lower than it would be following a faithful implementation of the Basel Framework.[12] This relief will, however, be higher during the transitional phase. In the light of this it will be important to regularly review the effects and appropriateness of the deviations from the Basel standards against their stated policy objectives to determine whether such deviations remain justified. Ultimately, the BCBS will assess the EU implementation at a later stage, as well as implementations in other BCBS jurisdictions’, in forthcoming RCAPs.

It should be noted that Basel III is a minimum framework. Basel members therefore reserve the right to adopt standards which are more stringent than those required by the framework (“gold-plating”) and to implement the measures more quickly.

The standardised approach applies by default and determines the risk weights allocated to a certain category of assets.

All banks need to obtain permission from their supervisor if they wish to depart from the standardised approach and use their internal models to calculate RWAs.

See BCBS (2022), “Evaluation of the impact and efficacy of the Basel III reforms”, Bank for International Settlements, December.

The scope of the evaluation is limited to those elements of Basel III that had been implemented by 2019.

European Banking Authority (2019), “Basel III reforms: Impact study and key recommendations”, 4 December.

Budnik, K. et al. (2021), “Macroeconomic impact of Basel III finalisation on the euro area”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 14, ECB, 26 July.

For details of the Basel III timetable see BCBS (2020),“Governors and Heads of Supervision announce deferral of Basel III implementation to increase operational capacity of banks and supervisors to respond to Covid-19”, press release, Bank for International Settlements, 27 March.

The implementation date for the final Basel III reforms was extended by six months to 1 July 2025, while the transitional period was reduced by six months (to 4.5 years) in order not to delay the full implementation. See Bank of England (2023), “Timings of Basel 3.1 implementation in the UK”, press release, 27 September.

See “Agencies request comment on proposed rules to strengthen capital requirements for large banks”, joint press release, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 27 July 2023.

European Banking Authority (2023), “Basel III Monitoring Exercise – Results based on Data as of 31 December 2022 (ANNEX – Analysis of EU specific adjustment)”, September.