The persistence and signalling power of central bank asset purchase programmes

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the 2018 US Monetary Policy Forum, New York City, 23 February 2018

The financial crisis has seen central banks launch asset purchase programmes of unprecedented scope and scale, so as to provide additional policy stimulus as interest rates approached the lower bound. This period has yielded many insights into how these programmes work and their various channels of transmission.[1] But one question that has remained open is the relative importance of their “stock” and “flow” effects.

The issue is not so much about which of the two effects dominates. The literature is fairly clear on this: there are sizeable announcement effects related to the stock of purchases, and these effects materialise whenever investors receive new information about the parameters of the purchase programme, such as its size, duration and composition. The actual impact of purchase operations on yields has been found to be less in comparison.[2]

The issue is rather if it matters how a given stock of purchases is built up, and how this building up interacts over time with the other elements of the monetary policy stance. This is especially important for the ECB today because, as we said in our latest introductory statements, our monetary support currently comprises three components: first, net asset purchases; second, the stock of acquired assets and forthcoming reinvestments; and third, our forward guidance on interest rates.

I would therefore like to use my remarks today to explore two aspects of implementing asset purchase programmes where I still see open questions. My focus will be on the closed economy dimension of such operations, having addressed their international spillovers elsewhere.[3]

The first aspect relates to the interaction between interest rate forward guidance and asset purchases. Specifically, for a given policy intention, are policymakers able to choose the relative intensity with which they use each of these instruments? In other words, under what conditions will they become substitutes rather than complements?

The second aspect relates to the persistence of the effects of asset purchases. Does the stock effect appear mainly at the time of the announcement and then fade as new shocks occur? Or does it accumulate as the size of the central bank’s portfolio rises, meaning its effect can grow even as the flow of purchases is reduced?

I intend to argue that, at least in the euro area, empirical evidence suggests that the amount of purchases needed to deliver a given compression of the term premium is likely to fall over time as the acquired stock of assets increases. But crucially, once their policy objectives come closer to being achieved, central banks can safeguard low bond yields, if judged necessary, only to the extent they provide effective guidance on the future path of short-term interest rates.

Asset purchases and rate forward guidance

Let me start with the interaction between rate forward guidance and asset purchases.

A natural starting point for such a discussion is to recall the two main components that shape long-term interest rates: expectations of future short-term rates and a term premium. Asset purchase programmes can lower yields by influencing both components. Purchases compress term premia by removing duration risk from the market. And since investors do not expect central banks to start raising rates while they are still buying assets, purchases – in principle – also have a signalling effect for the expected rate path.

I would argue, however, that the strength of this signalling effect is likely to depend on the degree of uncertainty that investors have about the policy outlook. When the outlook is gloomy and investors expect rates to remain low for long, they typically don’t focus on signals that will tie the hands of the central bank in the future. What they want to see is a clear commitment by the central bank to counter the downside risks that are visible now. They want them to “put their money where their mouth is”.

But when policy has succeeded in shifting upwards the distribution of risks around the growth outlook, and expectations of an end to asset purchases start to mount, uncertainty about the future path of rates begins to increase. Then, the interaction between the horizon of the purchase programme and rate forward guidance becomes more important.

Let me illustrate this point by referring to our own experience of buying assets.

From the time we started purchasing assets in September 2014, to the time we expanded the programme to include public sector securities in March 2015, we observed a strong reaction in long-term yields as investors started to anticipate our future interventions. The ten-year Bund yield fell by nearly 80 basis points in that period alone. The launch of our asset purchase programme had undoubtedly erased concerns among market participants that the ECB might not be serious about achieving its price stability objective. We “put up”, in other words.

But when, in December 2015, we extended the programme by six months and announced the reinvestment of future principal repayments, the reaction was much less favourable. Although the extension of the programme alone increased the expected stock of purchases by €360 billion, the ten-year Bund yield rose by 20 basis points upon announcement.

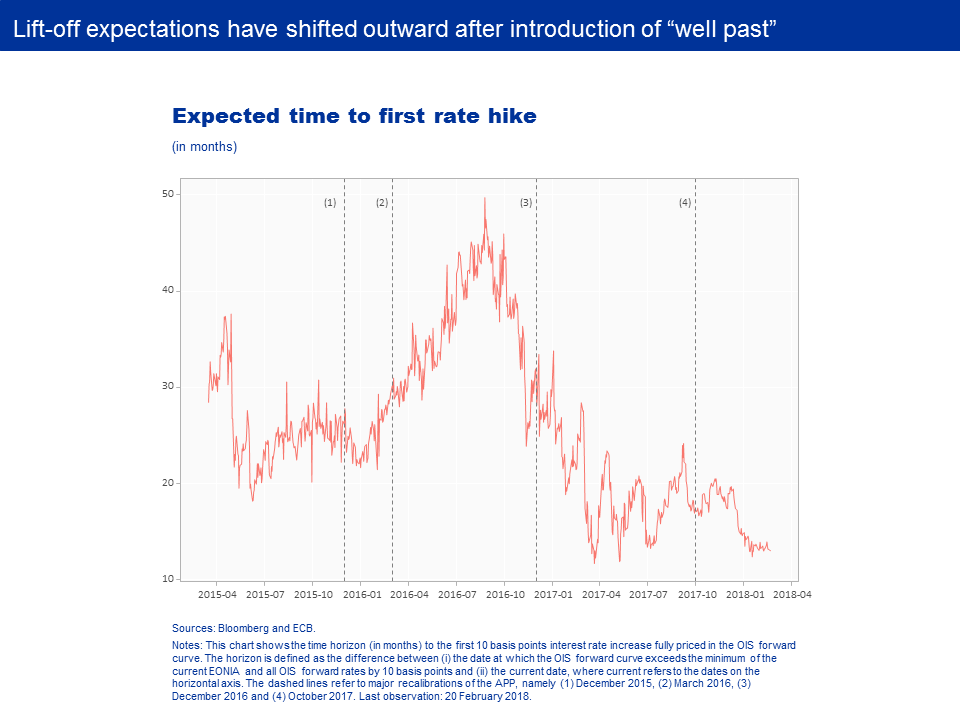

Clearly, market reactions were at odds with the standard thinking on the transmission of asset purchases. According to the signalling channel, our December 2015 actions should have helped to push out expectations of a rate lift-off. They should have provided strong forward guidance on the expected future path of short-term rates, thereby putting downward pressure on long-term rates. And the sizeable additional removal of bonds from the market should have weighed on term premia. None of this happened, however. As you can see on my first slide, the expected period of time until a rate lift-off in fact became shorter after our December 2015 announcement.

This suggests two things. First, it cannot be excluded that markets may have taken our backloaded actions – the extension pertained to a period that would only start nine months from the announcement date, while future reinvestments under the public sector purchase programme would not start until 15 months later – as a sign of hesitation on the part of the Governing Council to follow through on our commitment to bring inflation back to our aim. In the eyes of investors, we failed to “put up”.

This in turn implies, and this is my second point, that when markets perceive a central bank’s inflation aim to be at risk, asset purchases are a commitment device that reassures investors that the central bank is unwilling to tolerate a protracted period of low inflation, on top of their direct impact on financial conditions.

As such, the signal they send about the future path of short-term rates is of a secondary nature. Purchase pace and envelope are what matter most. This is also consistent with findings in the literature which show that the signalling effect of asset purchases is typically moderate at the time they are announced.[4]

However, we have also seen that, as the outlook improves, the signal that asset purchases send regarding the likely date of a first rate hike becomes increasingly important for anchoring the medium to long-term segment of the curve.

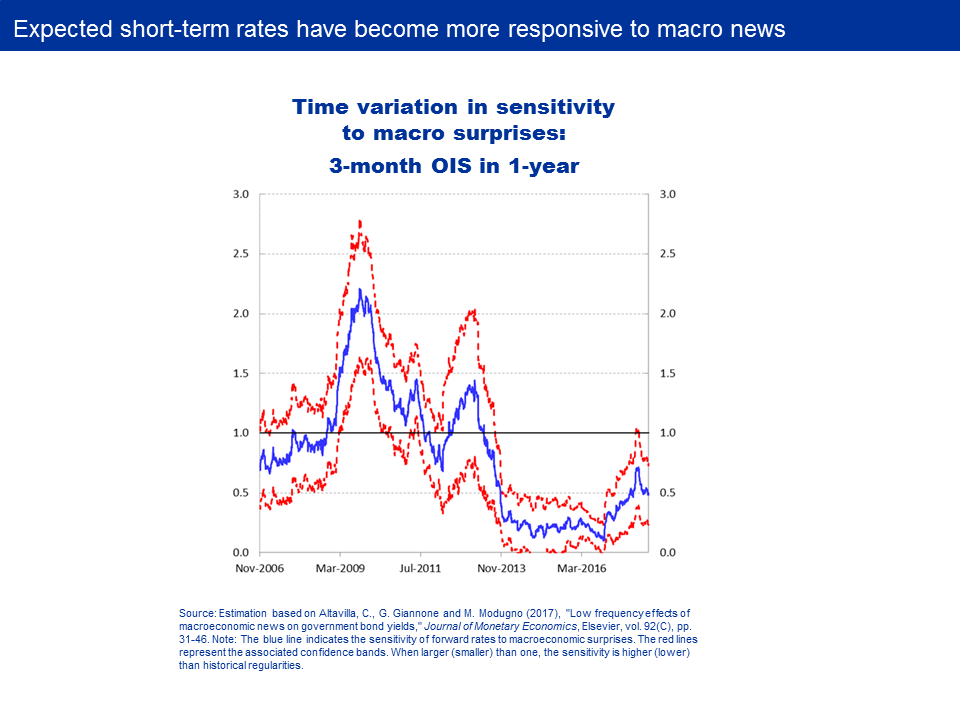

This can also be seen in the greater sensitivity of forward rates to macroeconomic news, as my next slide shows. As expectations of an end to asset purchases build up in the market, expected short-term rates in one year’s time have become increasingly more responsive to changes in the data.

At this point, the close relationship between expectations of a rate lift-off and the purchase horizon opens room for the central bank to recalibrate the relative intensity of the instruments it uses to secure appropriate financial conditions. For example, a shorter purchase horizon could be combined with stronger rate forward guidance so as to mitigate the risk of investors unduly bringing forward their rate expectations.

The terms of this recalibration will largely depend on three considerations.

The first relates to financial stability considerations – that is, the potential side effects of central banks being active players in bond markets for a protracted period of time. Should too long a presence unduly affect market liquidity or market structures, then this could tilt the balance away from purchases and towards stronger guidance on rates.

Of course, low-for-long short-term interest rates also have financial stability implications. But this is not the point. The point is that asset purchases are necessary at the lower bound to reinforce forward guidance, but this necessity gradually declines as the outlook improves.

The second consideration relates to clarity on communication, in particular when guidance on rates is linked to the end date of the asset purchase programme. In the ECB’s case, we have stated that we expect rates to remain at their present levels “well past the horizon of our net asset purchases”.

This has proved a powerful way to dispel concerns about expectations of a premature tightening as we gradually succeeded in shifting upwards the distribution of risks around the inflation outlook. You can see this clearly on my previous slide. After we introduced the notion of “well past” in March 2016, and increased the pace of purchases, the expected time to a lift-off was pushed out measurably.

But as a central bank gets closer to reaching its inflation aim, risks become larger that uncertainty around the horizon of purchases may inject volatility into the expected future rate path, even well ahead of the signalled purchasing intentions of the central bank.

This might not only affect financial conditions, but also blur the signals central banks rely on to gauge market expectations. For example, over the course of the last two months we saw a repricing in the EONIA forward curve. But it is difficult to tell with certainty whether this was the result of a re-appraisal by markets of the meaning of “well past” in our forward guidance – that is, a genuine adjustment of interest rate expectations – or merely a reflection of changes to the expected length of our asset purchase programme.

More clarity on future rates could then in principle help condense the focus of market uncertainty from two variables – the end-date of asset purchases and the definition of “well past” – to one variable, which the central bank can control with its communication.

This is in fact very similar to what my colleague Peter Praet had said recently, namely that “as we progress towards a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation and approach the time when net purchases will gradually come to an end, the residual monetary support needed to assist the economy in its transition to a new normal will increasingly come from forward guidance on our policy rates.”[5]

Importantly, this is not about the sequence of instrument normalisation. In the ECB’s case, the Governing Council has confirmed it repeatedly. It is rather about the ability of the central bank to effectively steer market conditions in a way consistent with its price stability mandate.

But whether it would in fact achieve this depends in part on the third consideration, namely the strength of the “stock effect” – that is, the persistence of the effects of the stock of bonds held by the central bank on its balance sheet under a commitment of reinvestment.[6]

If the effects of purchases dissipate quickly, a shorter purchase horizon could lead to term premia rising even as interest rate expectations remain well anchored by forward guidance. Financial conditions would then tighten.

But if the effectiveness of asset purchases rises with the stock of assets already acquired – if there is some “crossover point” where the stock effect becomes more important than the continued flow of purchases – then a reduced pace of purchases would not unduly decompress the term premium.

This brings me to my second question, which concerns the persistence of asset purchase programmes.

The persistence of asset purchase programmes: theory

Unfortunately, surprisingly little is known about this issue in the academic literature, mainly due to the preponderance of event studies in existing research.[7] Those studies have little to say about the persistence of asset purchase programmes long after they are announced. Other studies using time-series analysis suggest that the expected persistence of the supply shock is important.[8]

What I would like to offer today is a way of thinking about it which, I believe, could shed some light on how the stock effect of purchases works in practice, how it evolves over time and why it might differ between jurisdictions.

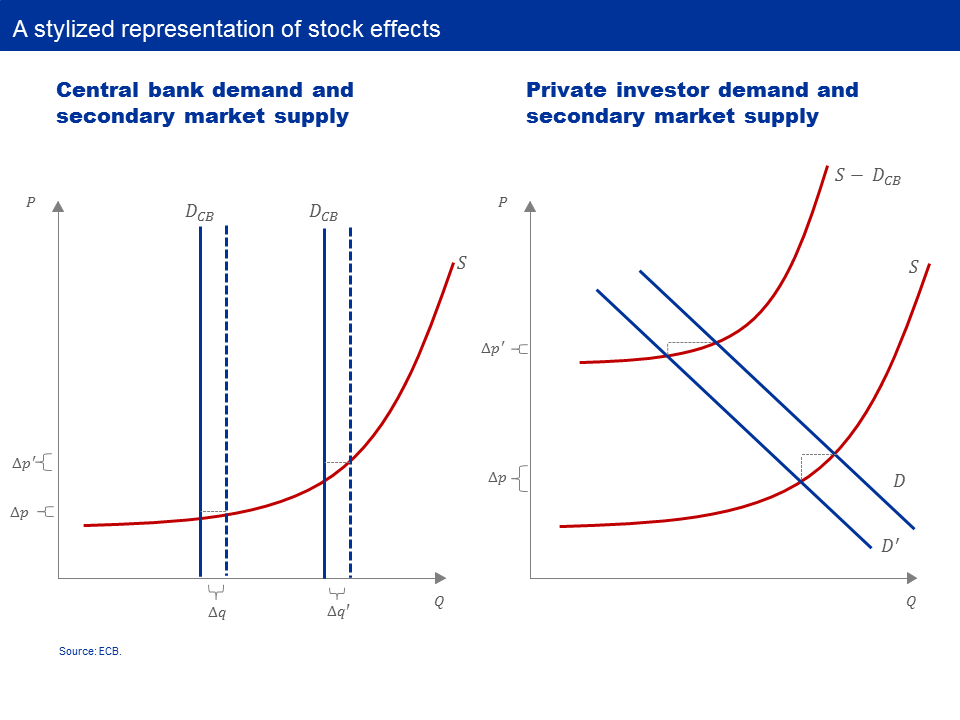

I will look at some of the empirical evidence in a minute, but I would first like to structure my thoughts with the help of a simple stylised supply and demand diagram like the one you can see here on the left-hand side of my next slide. This is an easy way to visualise the interaction between a central bank acting as a buyer of securities and potential sellers in the secondary market.

For ease of illustration, the demand curve of the central bank is vertical – that is, the central bank’s demand can be expected to be price-inelastic, by and large. Our objective is not to minimise costs or to maximise profits: it is to create the financial conditions required to achieve price stability. This is without prejudice, of course, to our legal requirement to act in accordance with the principles of an open market economy in which prices are discovered through private supply and demand.[9]

The supply curve, by contrast, is unlikely to be just a linear upward-sloping curve. It is likely to be a convex function. Let me explain why. As demand rises, supply is likely to become increasingly constrained. Inventory holdings by intermediaries shrink, while other marginal sellers are likely to have a higher reservation price.

For example, pension funds typically need to invest a significant portion of their assets in safe long-dated bonds to match their liabilities. Many other market participants need to keep high quality liquid assets for regulatory reasons. These investors will typically sell only for a higher premium.

It is now easy to see that the effectiveness of purchases can be expected to increase over time. A given outward shift of our demand curve, through, say, an extension of our asset purchase programme, will meet a supply curve that gets steeper as bonds become scarcer. The “bang for the buck” rises.[10]

On the right-hand side you can see how this translates into the stock effect.

Central bank asset purchase programmes effectively constrain the supply of bonds available to private price-sensitive investors. So you can think of it as an inward shift of the supply curve. However, the demand curve for private investors, unlike that for central banks, is unlikely to be price-inelastic. It is pictured here as a standard downward-sloping linear demand curve.

The implication is that if central banks have succeeded in shifting the supply curve sufficiently inwards, then prices may become less sensitive even when purchases start being reduced. Consider the example of an adverse demand shock, shown on the right-hand side – that is, investors will want to sell bonds as the economic outlook improves and expectations of higher rates mount.

You can see that the price impact of such a change in demand is likely to be more contained than in a situation where supply is greater. The reason is that any new supply would be absorbed with smaller price changes, given the scarcity of the underlying asset.

The persistence of asset purchase programmes: evidence

Both of these stylised representations are supported by the data.

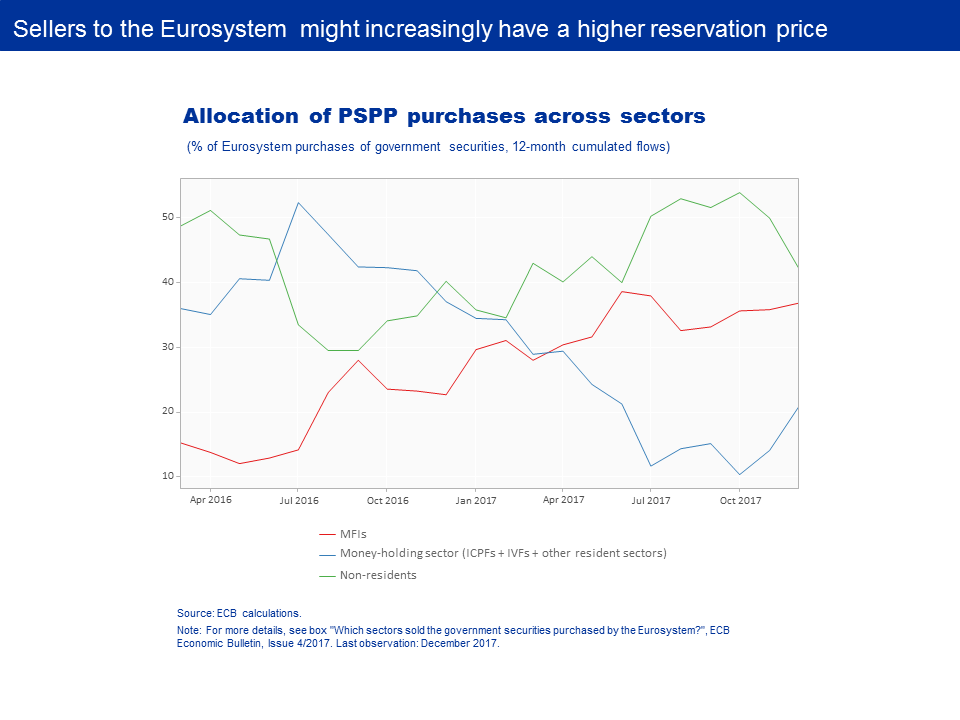

On my next slide you can see that, as our purchase programme has progressed, we have indeed seen a shift towards investors with a higher reservation price as marginal seller to the Eurosystem. We are now increasingly purchasing assets from pension funds and insurance companies rather than from non-residents, who are less likely to have a statutory need for euro area government bonds. The implication is that our purchases are likely to have become more effective over time.

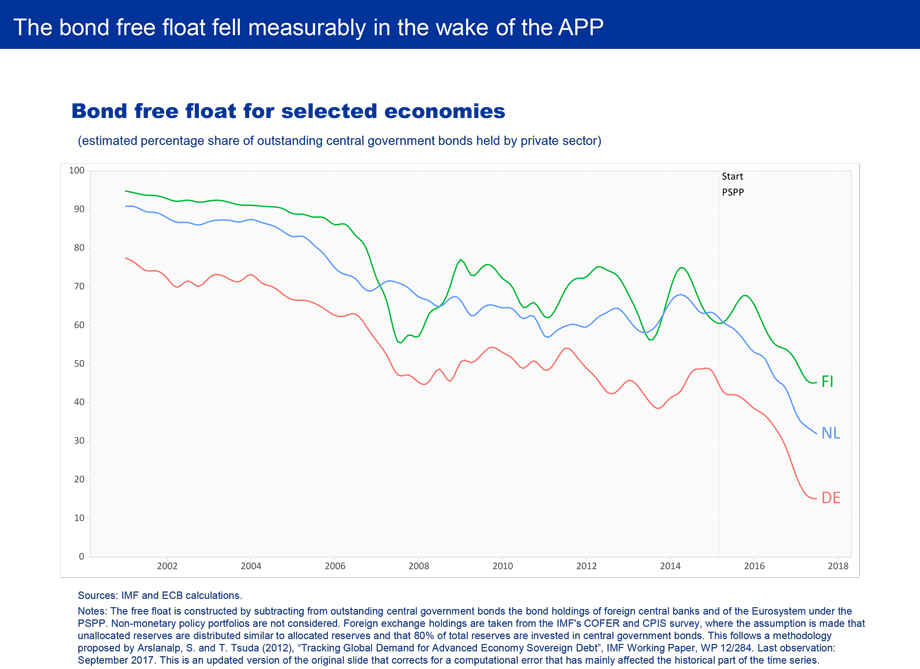

On the next slide you can see how the cumulative effect of these purchases on private bond supply has created the conditions for strong stock effects. What you can see here is an estimate of the share of outstanding central government bonds held by the private sector – the so-called “free float” – for three euro area countries that investors consider safe.

The free float is constructed by computing the fraction of outstanding bonds that is held neither by the Eurosystem under the public sector purchase programme nor by foreign central banks as part of their foreign exchange reserves. In each case the free float has shrunk significantly since our asset purchase programme began.

This is especially the case for German Bunds, which is of particular importance for the euro area as Bund prices effectively determine the quasi-risk free curve in the euro area. According to our estimates, less than 10% of the outstanding stock of German Bunds might currently be in the hands of private investors. But this estimate needs to be treated with caution as it relies on a number of assumptions regarding the allocation of overseas foreign exchange reserves.

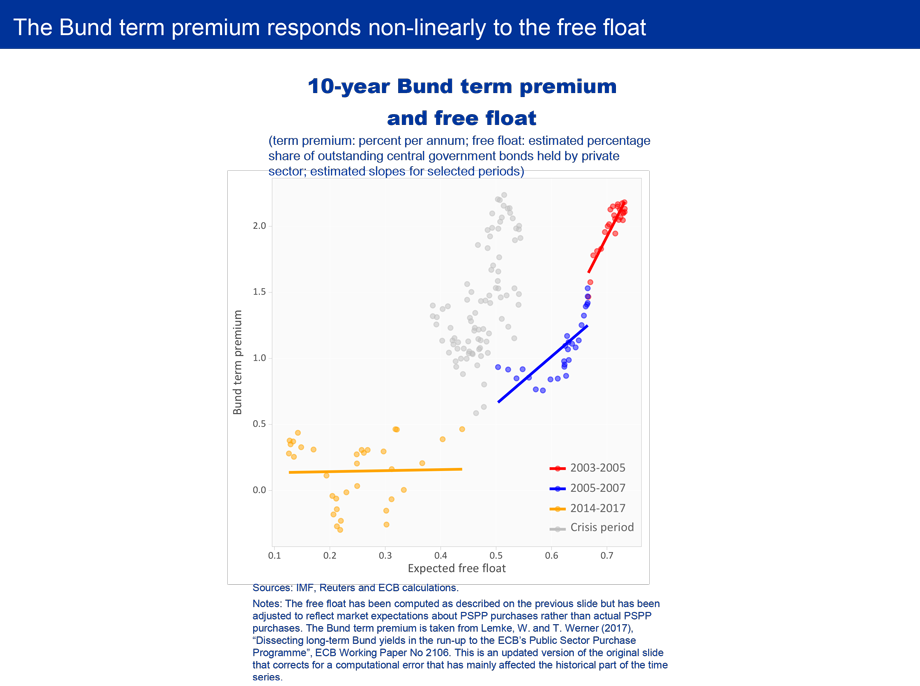

As my next slide shows, the drop in the free float has had a significant impact on price dynamics. What you can see here is the empirical relationship between the Bund free-float and the term premium investors require for holding long-term Bunds. We exclude here the period around the financial and sovereign debt crises.[11]

Two things stand out. First, there is a clear positive relationship between the amount of duration risk private investors are expected to hold and the compensation they require for holding it. Second, it is easy to see that the relationship is non-linear and that the term premium has become less responsive at lower free float levels. This is the stock effect at work.

The amount of bonds available to private investors is currently so low that investors are willing to absorb new bonds without requiring much higher compensation. Supply is effectively constraining demand. This becomes clear if we recall the statutory needs of many investors for safe and liquid assets. In these circumstances, only very large changes in the expected supply of bonds can cause yields to rise more meaningfully.

This framework helps us explain why, in the course of the last year, Bund yields traded in a tight corridor despite the measurable decline in our purchase pace from €80 billion per month in March 2017 to €30 billion as of January this year.

Of course, stock effects have not prevented Bund prices from falling in line with the strong economic recovery: an improving outlook will naturally drive yields higher as expectations of the future rate path are revised. But what stock effects have achieved is to temper the impact of both domestic demand shocks and foreign spillovers on euro area term premia.

In some ways, there are parallels with the discussion of nonlinearities in the Phillips curve: here too we see evidence that price increases only start to accelerate more forcefully once the economy moves into the steeper part of the curve. Unlike in the labour market, however, current and future reinvestments of principal repayments on our asset purchases should ensure that expected supply in the Bund market remains below the threshold at which price effects may increase in strength.

Squaring the stock effect in the United States and the euro area

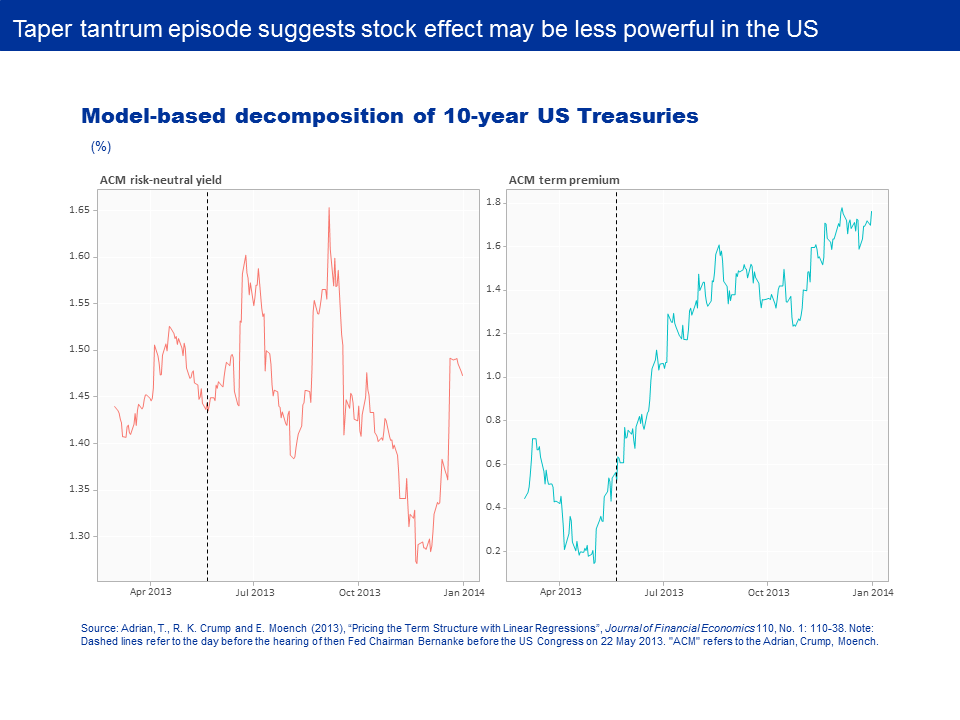

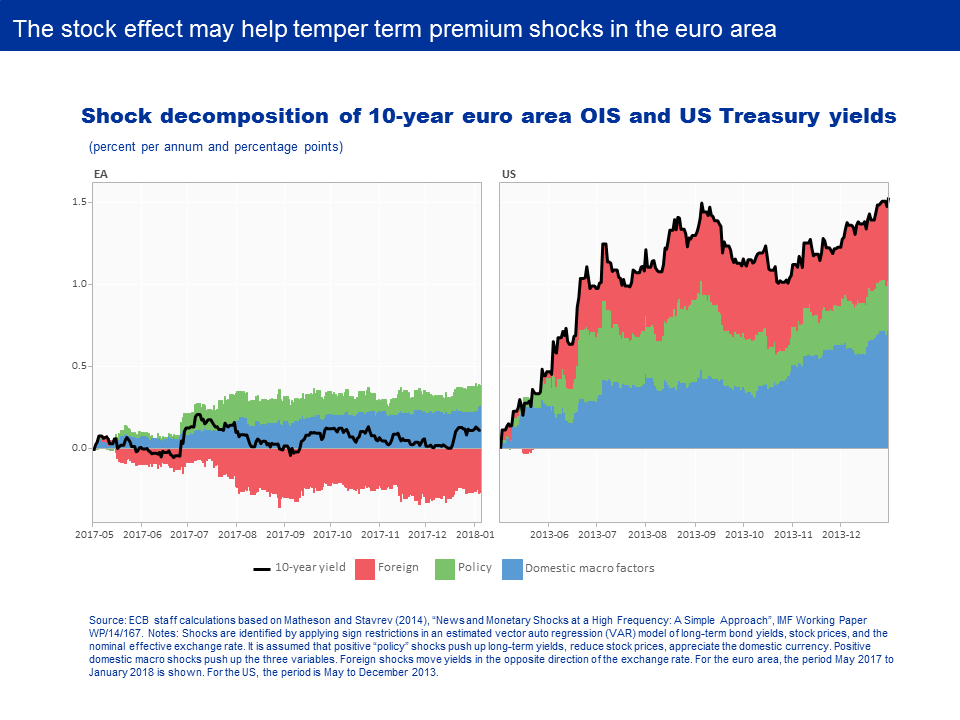

Another way of demonstrating the non-linear nature of stock effects is to consider the very different market reaction we saw here in the United States as expectations of an end to asset purchases mounted, in particular the famous “taper tantrum” in mid-2013.

Indeed, one argument put forward by those who are sceptical of the persistence of stock effects is that the announcement of tapering led to an immediate repricing of the market for US Treasuries. As you can see on my next slide, this cannot systematically be explained by an upward revision in interest rate expectations. Expected rates jumped twice but came back.

Rather, the repricing was driven by a steep and lasting increase in the term premium on ten-year US Treasuries – by more than 130 basis points in less than three months, as you can see on the right-hand side. This is hard to square with persistent term premium effects of central bank asset purchase programmes.

Yet, we have to remember that, even after various rounds of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve held only around 20% of outstanding marketable US debt at the time. Even when accounting for the holdings of other price-insensitive investors, such as foreign central banks, private investors still held around half of marketable US Treasuries. Remember that it may be less than 10% in the case of German Bunds.

In part, this reflects the fiscal environment prevailing at the time the asset purchases were taking place. Demand on the part of the Federal Reserve has consistently been lower than net new issuance. This means that private sector holdings of government bonds continued to grow while the Federal Reserve’s purchase programmes were in place, albeit at a slower pace than would otherwise have been the case. In the euro area, by contrast, purchases by the Eurosystem were significantly larger than new net issuance, producing a cumulative contraction in the share of privately held bonds.

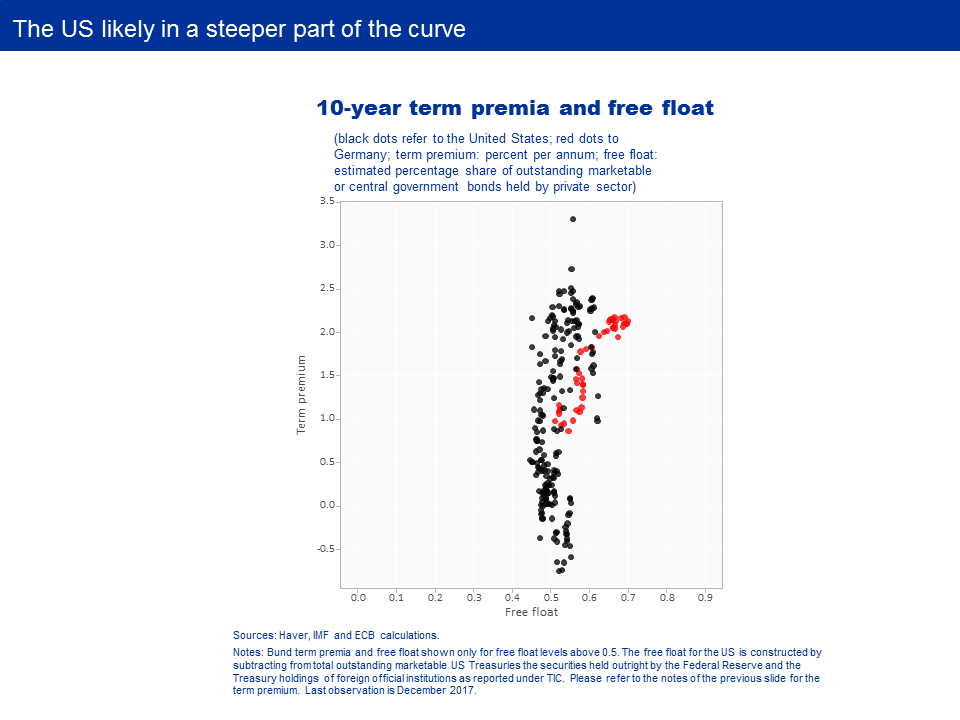

In other words, US Treasuries around the taper tantrum episode were likely still in sufficient supply to satisfy the demand of private investors, which made bond prices more sensitive. Indeed, on my next slide you can see the same relationship I just showed for the Bund for US Treasuries – that is, the ten-year Treasury term premium against the free float. These are the black dots.

You can see clearly that the United States was always in a steeper part of the curve, where supply was unable to anchor term premia. You can also see that at these levels of the free float, the relation between term premia and free float was not much different in the Bund market – you can see this when looking at the red dots.

On my next slide you can see how this might have affected market reactions in periods when the outlook had started to brighten. Here I show cumulative changes of a model-based shock decomposition of long-term yields, starting in May 2013 for the United States and in May 2017 for the euro area.

You can see that while in the United States a combination of macroeconomic, policy and foreign shocks were driving yields higher, in the euro area domestic shocks were appreciably more moderate, and foreign shocks were even putting downward pressure on yields. This happened despite a broadly comparable economic backdrop. Stock effects might therefore have helped to insulate the euro area from foreign spillovers and to temper domestic shocks.

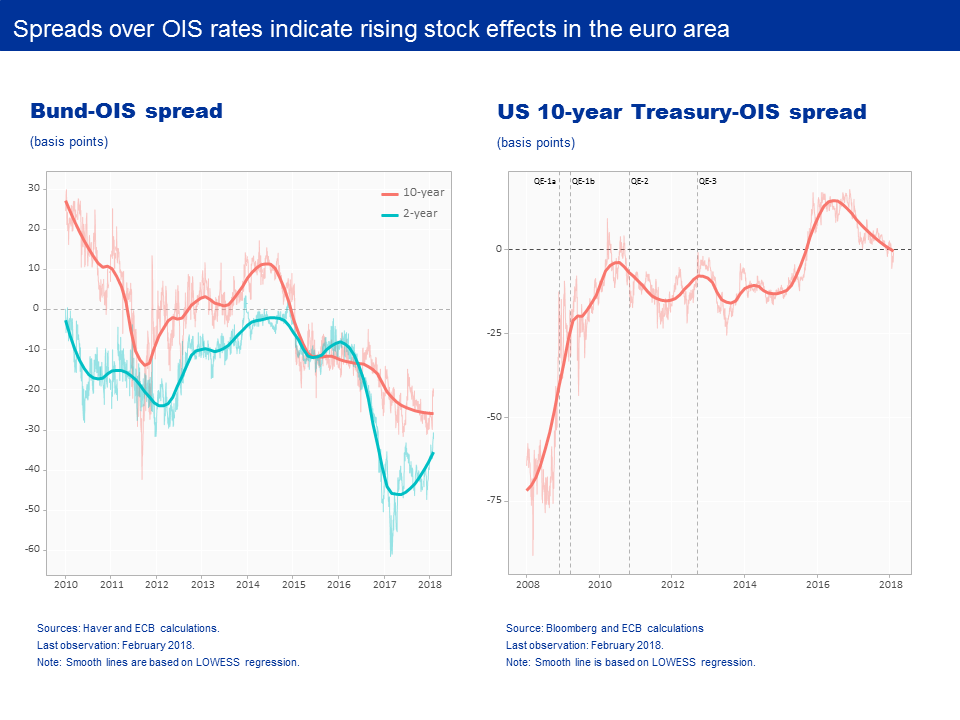

Bond yield developments relative to the overnight index swap (OIS) curve corroborate this view.

You can see from the left-hand side of the next slide that in the euro area, at both two-year and ten-year durations, the spread between German Bunds and corresponding OIS rates turned negative as we started implementing the asset purchase programme and consistently and gradually widened over time as the implementation of our asset purchases proceeded. This is a crude but reliable gauge of the effect of stocks on the term premium.

The reason is that, if changes in the Bund term premium were being driven by risk factors alone – say, higher inflation expectations or uncertainty about monetary policy – we would expect the Bund-OIS spread to be fairly constant. Such factors typically affect both markets as swap dealers use positions in Bunds to hedge interest rate risk on swaps. But the fact that the spread is widening over time suggests that it is not being driven by common factors, but rather by factors specific to the Bund market. The most plausible candidate for a secular effect of this kind is supply-demand effects induced by a shrinking free float.[12]

In the United States, by contrast, as you can see on the right-hand side, the ten-year spread was negative at various points during the three quantitative easing programmes, but there was no persistent widening as we have seen in the euro area, suggesting a role for factors other than bond scarcity caused by central bank interventions.

Conclusion

So what are the implications of all this for future monetary policy?

The non-linear nature of the stock effect implies that the amount of purchases needed to deliver a given compression of the term premium is likely to fall over time as the acquired stock of assets increases. Once the “crossover point” has been passed, additional purchases become less necessary to contain the term premium at low levels.

With the current share of the Bund free float constituting only a small fraction of the total outstanding, we can be confident that we have passed this threshold in the euro area, in particular as current and future reinvestments will ensure that the amount of duration risk to be borne by price-sensitive private investors will increase only very moderately over time.

This means that, in the future, the Eurosystem can retreat as buyer in the market without risking an unwarranted decompression of the term premium. But it can contain volatility, and safeguard appropriate financial conditions, only to the extent that it provides effective guidance on the expected future path of short-term interest rates.

Thank you.

[1] See, e.g., Krishnamurthy, A. and A. Vissing-Jorgensen (2011), “The Effects of Quantitative Easing on Interest Rates: Channels and Implications for Policy”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall; and Andrade, P., J. Breckenfelder, F. De Fiore, P. Karadi and O. Tristani (2016), "The ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme: An Early Assessment", ECB Working Paper No 1956.

[2] See D’Amico, S. and T. B. King (2013), “Flow and stock effects of large-scale Treasury purchases:evidence on the importance of local supply”, Journal of Financial Economics 108(2): 425–448; and De Santis, R. and F. Holm-Hadulla (2017), “Flow effects of central bank asset purchases on euro area sovereign bond yields: evidence from a natural experiment”, ECB Working Paper No 2052.

[3] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “The international dimension of the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the Foreign Exchange Contact Group meeting, 11 July; and Cœuré, B. (2017), Monetary policy, exchange rates and capital flows”, speech at the 18th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., 3 November.

[4] See, e.g., Altavilla, C., G. Carboni and R. Motto (2015) “Asset purchase programmes and financial markets: lessons from the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No 1864; and Gagnon, J., M. Raskin, J. Remache, and B. Sack (2011), “The Financial Market Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchases”, International Journal of Central Banking 7 (1): 3–43.

[5] See Praet, P. (2017), “Communicating the complexity of unconventional monetary policy in EMU”, speech at the 2017 ECB Central Bank Communications Conference, Frankfurt am Main, 15 November.

[6] In what follows I neglect the possible impact on the term premium of the declining duration of the acquired stock of assets.

[7] See, e.g., Gagnon et al. (2011, op. cit.), Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen (2011, op. cit.), and Altavilla et al. (2015, op. cit.).

[8] See Li, C. and M. Wei (2013), “Term Structure Modeling with Supply Factors and the Federal Reserve's Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programs”, International Journal of Central Banking, 9(1), 3-39; Greenwood, R., S. Hanson and D. Vayanos (2015), “Forward Guidance in the Yield Curve: Short Rates versus Bond Supply”, NBER Working Paper No 21750; and Blattner, T.S. and M. Joyce (2017), “Net debt supply shocks in the euro area and the implications for QE”, ECB Working Paper No 1957.

[9] This is one reason why, for example, the ECB’s asset purchases in sovereign bond markets are subject to an issue and issuer limit.

[10] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Asset purchases, financial regulation and repo market activity”, speech at the ERCC General Meeting on “The repo market: market conditions and operational challenges”, Brussels, 14 November.

[11] During the crises, term premia were often affected by the extraordinarily high degree of uncertainty and volatility, which makes them much more difficult to interpret.

[12] For an early discussion see Cœuré, B. (2017), “Bond scarcity and the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the Club de Gestion Financière d’Associés en Finance, Paris, 3 April.

Banca Centrală Europeană

Direcția generală comunicare

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt pe Main, Germania

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproducerea informațiilor este permisă numai cu indicarea sursei.

Contacte media