Western Democracy and its Discontents: Economic and Political Challenges

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Aspen Transatlantic Dialogue: “Western Democracies under Pressure”, Rome, 14 October 2010

The theme of this conference, especially this first session, which concerns the ability of democratic systems to cope with the challenges of economic and financial crisis, has been addressed in the past by distinguished scholars such as Ralf Dahrendorf. He observed that:

“To stay competitive in a growing world economy [the OECD countries] are obliged to adopt measures which may inflict irreparable damage on the cohesion of the respective civil societies. If they are unprepared to take these measures, they must recur to restrictions of civil liberties and of political participation bearing all the hallmarks of a new authoritarianism...The task for the first world in the next decade is to square the circle between growth, social cohesion and political freedom.”[1]

This comment was written in the mid-1990s, but the current crisis makes it even more pertinent. It’s an expression of doubt about the ability of (so-called) advanced countries to be able to take unpopular but necessary measures to overcome the crisis that is prompting financial markets to disinvest, or even bet on those countries’ bankruptcy, resulting in an outflow of capital that prolongs the crisis.

What lessons can we draw from this crisis in respect of the functioning of democratic systems, and in particular their ability to meet the challenges of the global economy? Let me try to provide some answers, starting with three thoughts on the current crisis.

The first one concerns the causes of the crisis. Reams of commentary have been produced on the factors that unleashed it. Some commentators have focused on the shortcomings of the financial regulations, or on the ineffective supervision of markets and market participants. Others have pointed to the excessive monetary expansion in some countries. Others still have remarked that the lack of international coordination has generated large global imbalances. There is a grain of truth in each of these analyses. But if we stay at this level of detail we risk missing the essence of the problem and not finding a remedy for it. We have to ask why the regulations were inadequate, why monetary policies were so loose, why international cooperation was insufficient. Were they simple human errors, or errors caused by factors more deeply rooted in our societies – ones which touch on the subject of today’s discussion?

Few have embarked on this kind of reflection – an essential one if we are to understand the crisis and how to get out of it. Raghu Rajan, for example, takes as a starting point the increase in inequality that has occurred in recent years in advanced societies. It has resulted in a stagnation of the incomes of the middle classes. [2] Technological change in recent years has increased the productivity gap in various sectors of the economy and led to sharp differences in income. Another contributing factor has been, in my view, the rapid change in the comparative advantage of advanced economies associated with the globalisation process, which has hurt the less well-educated members of the population.

Technological change and economic integration have been taking place for centuries and have driven economic systems towards new equilibria in which well-being has generally increased for all. There is no reason why these processes should come to an end now. But they involve periods of transition during which a significant dislocation of resources may take place and some segments of the population may incur a relative impoverishment. Economic growth may even slow down and make the inequalities worse. The transition may also persist if the factors that triggered the changes are systemic in nature and scale, as is the shift by hundreds of millions of people to the market economy which started in the late 1980s.

It is during the transition that financial engineering comes into play. Finance makes it possible to bring the future forward. Those who expect an increase in income can, thanks to new financial instruments, i.e. debt, immediately increase their consumption and move on to a higher standard of living. They can, say, purchase a house, send their children to college and buy a powerful car. Financial engineering meets the needs of those who are not yet able to afford them, increases the revenue of financial institutions – and thus of the shareholders and managers – and raises government revenues too. Financial engineering helps to solve the transition problems of advanced societies facing changes arising from technological innovation and globalisation, especially for the poorer segments of the population. Financial innovation is thus favoured and encouraged by all the political forces, as Rajan notes. This explains the “affordable housing” measures taken by the Clinton administration and the “ownership society” of the Bush administration. Financial innovation has also been facilitated by the interest rates kept low for an extended period of time.

The problem arises – and arose – when the transition to the new equilibrium is very long, longer than expected. If the transition is longer than expected, financial engineering is no longer a solution and can become a problem. The debt burden becomes unsustainable and cannot be repaid, starting by the less well-off, whose incomes do not keep pace with property values inflated by low interest rates. The sub-prime crisis was created by excessive debt, taken on not by the wealthy, as happened on other occasions in the past, but by the less well-off, whose relative position in society was slipping. Debt had given them the illusion of being able to live for a few years beyond their means.

The gist of this first thought is that the crisis sprang from an unsuccessful attempt to square Dahrendorf’s circle. The failure involved not recognising that technological and global processes bring about a longer and more difficult than expected transition for one part of the population. It consisted of deluding oneself that such a transition can be facilitated by easy debt and low interest rates. Recognising this failure is the first step towards not failing again.

The second thought comes from the way in which our societies have responded to the crisis. Without making a value judgement, but considering only the efficiency and timeliness of actions that have been implemented to tackle the crisis and counter its negative effects, there is no denying that in most cases the reaction has been slow. This slowness has added to the cost of the crisis itself and to the scale of the adjustment required. Let me offer a couple of examples. If Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy had been avoided in September 2008, through an effective and timely intervention, there would probably not have been the collapse of confidence that in the months thereafter affected the global economy. The rescue package – TARP – would very probably have been much less than the USD 700 billion needed to restore calm to the markets. In Europe – to take another example – if the Greek government had decided to intervene with corrective action as early as autumn 2009, having just discovered the budget hole left by its predecessor, it could have avoided the sovereign debt crisis and the drastic adjustment programme which it then had to put in place under pressure from the markets. If the European countries had agreed in early February to provide financial support for Greece’s adjustment programme, they would probably have avoided the escalation of tensions in the markets last spring and the associated crisis of confidence. They would have avoided paying out the enormous sums which became necessary when Greece lost access to the financial markets.

These examples show that in developed countries the economic policy measures necessary to maintain the confidence of the markets tend to be taken only when markets are on the brink or in the middle of a crisis. Only under pressure from the markets do governments seem to find the strength and the consensus to adopt the necessary measures to ensure financial stability. This increases the scale of the adjustment required and consequently the negative repercussions for the economy. The doubts about the ability of governments to take the necessary measures in turn increases the distrust of financial markets and tends to intensify the crisis.

How does this vicious circle come about? Let me try to identify some factors that characterise the problems that our societies face in reaching a consensus on decisive action in a crisis.

The first factor concerns how the financial crisis is perceived by the public and sometimes even by economic policy-makers. In our affluent societies, accustomed to economic growth and well-being, most people do not understand the risks to financial stability. Moreover, there were few, even in the inner circle of decision-makers, who understood the gravity of the situation in which the markets found themselves in early May this year.

The second factor is that, in the face of systemic crises, such as the one through which we have passed, those who govern must sometimes take decisions that infringe long-term rules. The most striking case is the rescue of a bank or a country. In theory this should not occur because taxpayers' money should not be used to save those who have misbehaved or failed to comply with the rules. But in some cases it is necessary in order to avoid a systemic crisis that can have even more devastating effects. In a democratic system it is very difficult to convince voters, especially if they do not perceive any imminent danger, that in some cases a discretionary interpretation of the rule is needed to avoid the worst. This was shown clearly in Europe when it came to deciding on the support package for Greece. In the U.S., the administration was unable to go against the widely held sentiment, which was opposed to the use of public funds to save a bank, and decided to let Lehman Brothers fail. The subsequent rescue of AIG to avoid panic and financial ruin then turned out to be much more expensive for taxpayers. Fortunately we avoided this in Europe.

Let me move on to my third and last thought. It concerns the post-crisis period. The industrialised countries are emerging from the crisis poorer, more indebted and with lower prospects for growth. The process of fiscal consolidation must remain the cornerstone of economic policy and form the basis for a radical overhaul of the economies in order to create more growth. But in the current environment I see two risks facing our democracies in the coming years.

The first one is the illusion that this crisis is cyclical rather than structural, that it has no impact on the long-term growth potential of our economies. We may, in this case, be deluding ourselves that traditional macroeconomic policies (monetary and fiscal) are per se able to restore growth to pre-crisis levels. Thus there is a risk of triggering again unsustainable policies which in turn create new imbalances that sooner or later implode.

The second risk is an attitude of resignation, of being resigned to not having the capacity and strength to untie the knots that restrict our growth potential, or of being resigned to economic stagnation. This state of mind is associated with the politician’s dilemma neatly articulated by the President of the Eurogroup, Jean-Claude Juncker: “ We all know what to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we have done it”. This type of reasoning occasionally leads some people to argue that democratic systems are not up to making our societies swallow the medicine needed in order to grow again. Structural reforms in fact involve a redistribution of income to the detriment of the less efficient sectors, which are characterised by monopolistic rents and are strongly opposed to change. The idea is often floated that some emerging countries are better able to manage the current crisis because they have ‘stronger’ regimes, which do not need to justify their actions vis-à-vis their electorates very often.

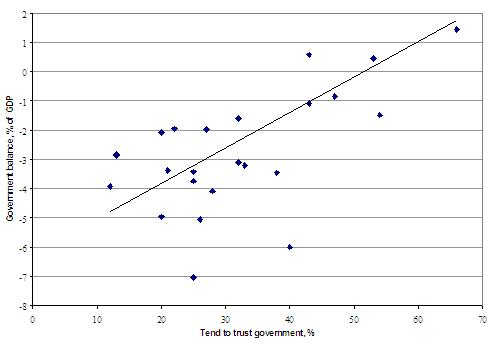

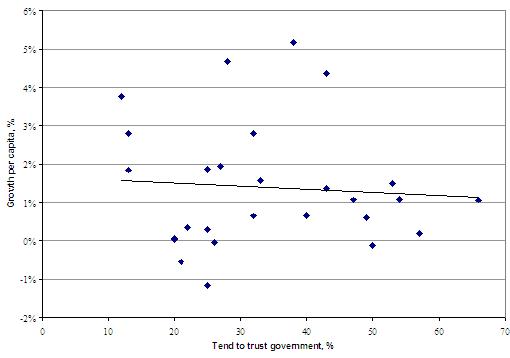

These are dangerous positions in my view and are not justified by empirical evidence. Juncker’s provocative remark is not in fact substantiated by the facts. He himself is one of Europe’s veteran political leaders, who has brought rigour and development to his country and was re-elected three times in a row. An analysis of the correlation between economic variables and political popularity in Europe reveals that, contrary to what many believe, budgetary austerity and reforms do not penalise governments. Indeed, in recent years in Europe there has been a positive correlation between political popularity and budgetary rigour (see Chart 1). The correlation is much stronger than the one between political popularity and economic growth (see Chart 2), which indicates that, for a given level of growth, healthy public finances reward governments. This suggests that political leaders who have the courage and the ability to reconcile balanced public finances with the economic growth are rewarded over time.

Democratic systems should not to be blamed if advanced economies risk stagnation and do not grow. They are in danger only if people succumb to the illusion or become resigned to thinking that democracies do not allow change. Centuries of history demonstrate just the opposite: that without democracy there is no change, and sooner or later there is decline.

Thank you for your attention.

Chart 1: Trust in national government vs. government balance (average 2005-2009) – EU

Sources: Eurostat, Eurobarometer and ECB calculations.

Note: “Tend to trust government” is the proportion of respondents to the May 2010 Eurobarometer survey who reported trusting their national government.

Chart 2: Trust in national government vs. growth per capita (average 2005-2009) – EU

Sources: Eurobarometer, EC and ECB calculations.

Note: “Tend to trust government” is the proportion of respondents to the May 2010 Eurobarometer survey who reported trusting their national government.

-

[1] R. Dahrendorf, “Quadrare il Cerchio. Ieri e Oggi.”, Laterza, 2009.

-

[2]R. Rajan, “ Fault Lines”, Princeton University Press, 2010.

Banca Centrală Europeană

Direcția generală comunicare

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt pe Main, Germania

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproducerea informațiilor este permisă numai cu indicarea sursei.

Contacte media