The monetary policy implications of ageing

Speech by Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the ECBABP Conference on Pension Diversity and Solidarity in Europe,Maastricht / Heerlen, 26 September 2007

[SLIDE 1]

Ladies and gentlemen, [1]

I would like to thank the ABP Pension Fund for inviting me to this Conference on Pension Diversity and Solidarity in Europe. It is a pleasure to stand in front of such a distinguished audience to discuss one of the challenges to be confronted by many economies around the globe, a challenge that will be with us for the next decades: ageing and its macroeconomic implications.

[SLIDE 2]

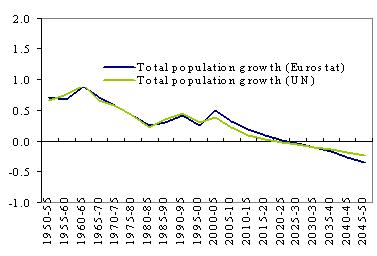

The ageing of the population in most industrialised economies and in the euro area in particular can be best characterised by a number of major demographic developments that have taken place over the last 60 years (Chart 1).

[SLIDE 3]

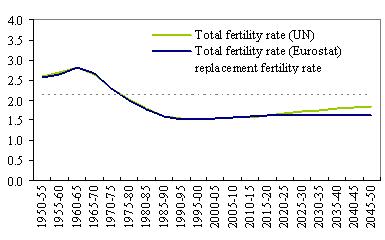

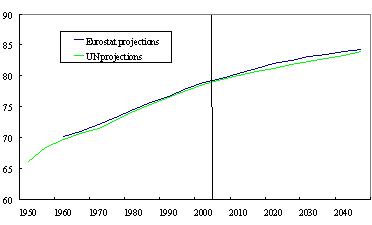

First, the baby-boom generation is moving closer to retirement age, while the fertility rate has almost halved in the euro area since the 1960s and now lies below the replacement rate (Chart 2). [2] And second, people live longer: more precisely, life expectancy has lengthened by eight years in the last four decades (Chart 3). [3]

[SLIDE 4]

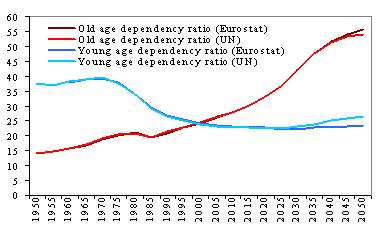

As a result, the old-age dependency ratio, defined as the number of individuals over the age of 65 per working-age person, is expected to almost double in the euro area over the next four decades [rising from around 0.3 in 2005 to around 0.5 by 2050 (Chart 4)]. More importantly, in the absence of significant structural reforms, the old-age economic dependency ratio, which is the number of individuals over the age of 65 per employed person, in the European economies could jump from 0.9 in 1995 to 1.2 by 2050. [4]

These developments could have significant macroeconomic effects. For instance, according to estimates from the European Commission and the Economic Policy Committee’s Ageing Working Group, the potential growth rate of output in the euro area could fall from 2.1% on average over the period 2004-2010 to 1.2% on average over the period 2031-2050 [5] accompanied by significant declines in savings and investment rates.

Not surprisingly, therefore, increasing attention is being paid to the economic implications of demographic developments. In Europe, the analysis carried out under the auspices of the Economic Policy Committee’s Ageing Working Group has significantly raised awareness of the effects of ageing on the fiscal burden among policy-makers and amongst the general public. In my remarks today, however, I will take a different but complementary perspective, and focus on the impact that ageing populations can have on the macroeconomic environment in which central banks operate.

In this regard, the demographic developments I have just described are not the types of shock that may trigger significant and immediate monetary policy responses. [6] This notwithstanding, financial markets may already be anticipating some of the effects of population ageing on asset prices, which are of indisputable relevance for monetary policy-makers. Consequently, in this speech I would like to share with you some thoughts based on the findings of the economic literature regarding, first, the effects of demographic change on the main macroeconomic variables and, second, the implications for the conduct of monetary policy.

I. The effects of population ageing on the economy

The potential impact of ageing on the economy is fairly complex. I will devote the first part of my speech to describing some of the potential effects of ageing on key macroeconomic variables. Ageing will mainly affect our economies through changes in the balance between savings and investment. Changes in savings and investment rates are expected to bring about adjustments in real interest rates, which could be partly tempered with international flows of production factors. I will also give an indication of the order of magnitude of the impact of population ageing on these key macroeconomic variables, while keeping in mind that such empirical estimates are surrounded by large margins of uncertainty.

I.1 Domestic savings

One of the main tenets of the life-cycle theory is that individuals try to smooth consumption over their lifetime. [7] As income tends to be relatively lower when individuals are either very young or retired, their savings typically follow a hump-shaped pattern, with a higher savings rate during their working life. For a given retirement age, population ageing increases the proportion of households with a relatively lower savings rate in the economy and therefore tends to reduce private savings. While estimates of the impact of a change in the age structure of the population on private savings have to be treated with caution, their order of magnitude clearly shows that population ageing will tend to dampen savings. The literature has estimated that a 10 percentage points increase in the old-age dependency ratio could reduce the savings rate by around 9%. [8], [9] Simulation exercises based on models that assume that households behave as predicted in the life-cycle theory have found that the private savings rate in the European economies could fall from 15.9% of GDP in 1990 to around 4.5% by 2060. [10]

One factor that may moderate this decline in private savings rates is increased longevity. Higher life expectancy may raise the rate at which individuals want to save during their working lives, partially reversing the effect which stems from higher old-age dependency ratios. [11] Life expectancy in the euro area is projected to increase by around five years over the next four decades [12], but its positive effect on domestic savings is not likely to offset the impact of the increasing old-age dependency ratios that I just mentioned.

[SLIDE 5]

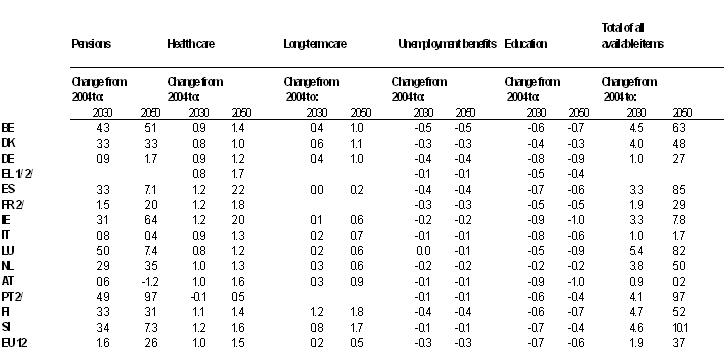

Turning now to public savings, population ageing is expected to exert considerable pressure on public finances (Table 1). [13] In the context of the current pay-as-you-go pension schemes that exist in many euro area countries, an ageing population implies that the number of beneficiaries increases while the number of contributors to the system shrinks. In the absence of significant reforms in pension systems, the Economic Policy Committee’s Ageing Working Group estimates that the costs related to old-age pension schemes will push government expenditure up by 2.6% of GDP in the euro area by 2050. [14] For some countries the estimated impact is much larger.

The ageing process will also negatively affect public finances via higher healthcare and long-term care costs, since older populations are more likely to make use of healthcare services, which, to a large extent, are provided by the public sector in Europe. Quantitatively, public healthcare costs are projected to increase by between 1% and 4% of GDP over the period 2000-2035, exacerbating the fiscal imbalances just discussed. [15] Interestingly, the OECD arrives at even higher estimates regarding the budgetary costs of ageing, using different (and possibly more realistic) assumptions. [16]

In summary, the ageing process may lead to a substantial fall in both private and public savings, with the savings rate in the European economies possibly falling by 5-6 percentage points over the period 2000-2050. [17]

I.2 Investment

Now that I have briefly described how population ageing is likely to induce a decline in domestic savings, let me turn to its effects on investment. The main determinant of investment is its expected real return. The productivity of physical capital is typically influenced by two main factors: technological progress and the capital intensity of the production process. While it is not straightforward to identify clear links between ageing and technological progress, the literature has explored how demographic developments could affect capital intensity.

The degree of capital intensity in the economy depends on the relative abundance of the different productive factors: the capital stock and the labour force. All other things being equal, ageing would presumably generate a fall in the rate of growth of the labour force, if not a contraction in its size. [18] The production process would therefore become more capital-intensive and the relative productivity of new capital purchases would be lower. Consequently, investment rates are expected to decelerate, and the growth rate of capital stock could gradually decline to better accommodate the relatively scarcer labour force.

I.3 Implications for equilibrium real interest rates

When thinking about long-term macroeconomic developments, which take time to run their course, it is helpful to try to quantify the real interest rate which, over those extended horizons, equalises domestic savings and investment. Now, the predicted declines in investment and savings described so far make the expected effect of ageing on the equilibrium real interest rate ambiguous. If investment decelerates or falls faster than domestic savings – at each level of aggregate income – the real interest rate that clears the market for loanable funds is expected to fall, since it is difficult for savers to find profitable investment opportunities. Alternatively, if domestic savings were to fall faster than investment, the real interest rate would rise to reflect the relative scarcity of financial funds.

Which effect is likely to dominate? Is this effect economically important? Simulation analyses, based on general equilibrium models accounting for both investment and savings, allow us to gauge the likely impact of population ageing on the real rate of interest which equalises savings and investment. The results of such exercises suggest that ageing is likely to lead to a moderate reduction in real interest rates in the European economies. Although the savings rate is expected to fall, the quicker projected drop in investment could push the equilibrium real rate down by around 50 to 100 basis points over the period 1990-2030, followed by a partial recovery by 2060 as the baby-boom effect disappears. [19]

This prospective decline in the real rate that equalises savings and investment could be noticed in forward-looking financial markets. So although the actual impact of the evolving demographic structure on the equilibrium real rate in the capital markets is something that is expected to occur with a considerable lag, some economists have suggested that expectations of such developments may have already started to exert some influence on the pricing of bonds. Among other things, these analyses suggest that ageing could have contributed to the “flattening” of the yield curve that has been observed over the recent past.

Such a conclusion, however, should be treated with a great deal of caution because it hinges on the assumption that capital market participants are perfectly forward-looking, an assumption which is questionable : if it is true that financial markets tend to overreact to short-term phenomena, the effects of ageing on the yield curve could be limited. [20]

More generally, it has to be taken into account that these quantitative simulations require a number of qualifications. On the one hand, some real-world factors may make the true decline in the equilibrium real interest rate larger than estimated in macroeconomic models. For example, older people may save more than predicted by the life-cycle theory if they want to leave a bequest to their heirs, putting additional downward pressure on the equilibrium rate. The degree of risk aversion may also change with age: if older people were systematically more risk-averse than the young, the accumulation of precautionary savings would lead to a higher than predicted savings rate and a lower than predicted real rate. [21] In addition, private savings rates may be significantly affected by pension reforms. [22]

On the other hand, there is another set of factors that may mitigate the estimated decline in real interest rates. For instance, models typically assume that population ageing does not affect the formation of human capital. With a gradual increase in the relative scarcity of labour, the return to education would be likely to increase, which would moderate the increase in capital intensity as the quality-adjusted labour input would not decline. [23] Such knock-on effects working through labour and possibly total factor productivity are typically absent from the available model simulations as they are quite difficult to quantify. Furthermore, the models used to simulate the impact of ageing on the macroeconomy are typically not designed to investigate how fertility rates may endogenously evolve with ageing. [24] Finally, these models do not usually take into account the effects of ageing on risk premia: if demographic developments were to lead to a substantial increase in government debt, resulting from a lack of sufficient pension reforms, the risk premia embedded in government bond yields would become larger, pushing interest rates upwards and undermining growth prospects. [25]

I.4 International factor flows

I have just mentioned that, as a consequence of ageing, a shortfall in investment relative to domestic savings would put downward pressure on the equilibrium real interest rate. While this is true in a closed economy, given that the European Union economy is to a large extent open, higher real wages could lure migration flows from countries with younger populations. At the same time, higher rates of return on savings outside the European Union could lead to capital flows in the opposite direction, thus mitigating the downward influence of demographics on the real rate prevailing in the domestic market.

A crucial aspect of demographics – seen from a global perspective – is the pace at which the different world economic areas age. Although there are differences in the pace of ageing between Europe, Japan and the United States, those between developing and developed countries are even larger. [26] Therefore, if production factors are internationally mobile, demographic factors may lead to sizeable flows between developed and developing economies, owing to significant differences in their demographic paths.

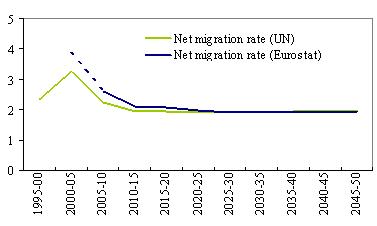

[SLIDE 6]

In principle, immigration could indeed mitigate the dramatic expected increase in dependency ratios which I described at the beginning of my remarks. However, the existing immigration policies in the European Union do not make it likely that there will be a significant increase in migration flows over the next decades. There are still legal impediments to labour mobility within the European Union and even within the euro area. On the basis of current information, international labour mobility is thus unlikely to prevent the labour force from falling in developed economies and particularly in the European Union (Chart 5). [27] In addition, we should note that large outflows of highly qualified young people from developing countries could have a very negative impact on the development prospects of those countries.

Analogously, capital outflows could mitigate the mild expected decline in EU equilibrium real rates because, all other things being equal, savers may look for higher returns in countries with younger populations and lower capital-labour ratios. Unfortunately, there is no consensus in the literature about the quantitative importance of this channel. While some foresee that European countries could experience current account surpluses of about 2% to 3% of GDP until 2040, [28] others hold the view that the OECD countries are less likely to large amount of savings because of less developed financial markets in non-OECD economies which increases the risk premia of investing in those economies and curtails the degree of capital mobility between OECD and non-OECD countries. [29] [30]

Summing up, population ageing is predicted to generate a faster fall in investment rates than in savings rates in most industrialised economies. The ageing process is therefore expected to contribute to a smooth and minor reduction in the equilibrium real interest rate over the next decades, while current account surpluses in ageing economies could partially mitigate this decline.

II. Implications of population ageing for the conduct of monetary policy

In the second part of my speech, I would like to address the possible effects of ageing on the monetary policy transmission mechanism and the objective of the central bank.

II.1 Monetary policy transmission mechanisms

Apart from the potential effects of ageing on the yield curve, how would the transmission mechanism of monetary policy change with an older population? According to the life-cycle theory, individuals accumulate financial wealth during their working lives to finance consumption during retirement. As a consequence, populations whose average age is closer to retirement are expected to have higher wealth-to-income ratios.

At the same time, expected imbalances in publicly financed pension schemes make it plausible to consider that an increasing number of retirees would rely more on their own accumulated wealth, as opposed to public pension provisions, to sustain their consumption levels. As a result, the fraction of the population exposed to asset price fluctuations could increase with ageing. [31] Therefore, the transmission channel of monetary policy may be affected by ageing. In particular, the so-called wealth channel, which links asset prices to consumption, may gain relative importance and play a more important role than in the past. [32]

II.2 Monetary policy objective

I would now like to stress that for a price-stability oriented central bank ageing also creates an environment in which the support for price stability will be reinforced.

I argued that a shift towards a demographic structure in which the elderly account for an increasing fraction of the population is expected to produce a gradual but persistent change in savings habits. This may have an impact on the demand for all classes of assets, although certain segments of the capital market are likely to be affected more substantially than others. If, for instance, older people are more risk averse and prefer to hold financial assets paying fixed-income returns, the demand for government bonds would tend to increase relative to riskier investment options, such as equity. [33]

In this environment, where a larger fraction of households’ wealth is invested in nominal assets, price stability would be even more important for households. [34] Stable prices ensure that the real value of both pension entitlements and savings is maintained and prevent arbitrary redistributions of income and wealth to the detriment of the most vulnerable groups in society, in particular pensioners. [35] This is why a credible commitment to maintaining price stability and, as a reflection, an orderly financial environment is and will remain so important for maintaining the standard of living of European citizens, particularly for the poorest and the most vulnerable.

III. Concluding remarks

All industrialised economies will be required to deal with the ageing of their populations during the first half of the twenty-first century. The consequences of this process for central banks are likely to be of a “slow-burn” nature. First, the real rate of interest that is expected to clear the capital market could mildly decline over the next decades, owing to a fall in investment rates that would probably more than offset the effects of expected lower private and public savings rates.

And second, escalating wealth-to-GDP ratios in ageing societies could render the wealth channel more important for the transmission of monetary policy actions, as the sensitivity of consumption and investment to asset prices is likely to increase.

These developments are important, and all central banks in the world are carefully studying these slow-moving forces as they unfold at their glacial pace. However, it is likely that the main challenges from ageing will not be for central banks. Fiscal policies and structural policies are in the forefront, as the most severe problems that ageing will pose for public policies are likely to come in the form of a dramatic deterioration in fiscal positions – owing to mounting pension expenditure – and a considerable reduction in the rate of growth of the labour force.

Hence, sound fiscal policies are especially important in the face of the major shift in demographic structures that confronts us. In addition, the implementation of structural reforms is key to averting the trend decline in potential output growth in an ageing society, because the reduction in the size of the labour force needs to be compensated for by increases in labour productivity and labour market participation.

As is always the case, the longer we wait to implement appropriate structural reforms, the more difficult it will be to counteract the possible adverse effects of population ageing on Europe’s future growth and prosperity.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Charts and tables

Chart 1: Total population growth in the euro area

Source: Maddaloni et al (2006).

Chart 2: Fertility rate in the euro area

Source: Maddaloni et al (2006).

Chart 3: Life expectancy (years) in the euro area

Source: Maddaloni et al (2006).

Chart 4: Old-age dependency ratio in the euro area

Source: Maddaloni et al (2006).

Chart 5: Net migration rate (per 1000 population) in the euro area

Source: Maddaloni et al. (2006).

Table 1: Projected impact of ageing populations on public expenditure

Source: European Commission (2006) reproduced in Maddaloni et al (2006).

Notes: These figures refer to the baseline projections for social security spending on pensions, education and unemployment transfers. For health care and long-term care, the projections refer to the “AWG reference scenarios”.

1) Total expenditure for GR is not reported owing to missing data.

2) Total expenditure for FR and PT does not include long-term care.

References

Abel, A.B. (2001), “Will Bequests Attenuate the Predicted Meltdown in Stock Prices When Baby Boomers Retire?”, Review of Economics and Statistics 83, pp. 589-595.

Abel, A.B. (2003), “The Effects of a Baby Boom on Stock Prices and Capital Accumulation in the Presence of Social Security”, Econometrica 71, pp. 551-578.

Auerbach, A.J., L.J. Kotlikoff, R.P. Hagemann and G. Nicoletti (1989), “The Economic Dynamics of an Ageing Population: The Case of Four OECD Countries”, OECD Department of Economics and Statistics Working Paper 62.

Bakshi, G., and Z. Chen (1994), “Baby Boom, Population Ageing, and Capital Markets”, Journal of Business 67, pp. 165-202.

Barro, R.J., and X. Sala-i-Martin (1990), “World Real Interest Rates”, NBER Working Paper No. 3317.

Batini, N., T. Callen and W. McKibbin (2006), “The Global Impact of Demographic Change”, IMF Working Paper 06/9.

Bean, C. (2004), “Global Demographic Change: Some Implications for Central Banks”, Overview Panel, FRB Kansas City Annual Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Becker, G.S., K.M. Murphy and R. Tamura (1990), “Human Capital, Fertility, and Economic Growth”, Journal of Political Economy 98(5), pp. S12-S37.

Börsch-Supan, A., D. Krueger and A. Ludwig (2007), “Demographic Change, Relative Factor Prices, International Capital Flows, and Their Differential Effects on the Welfare of Generations”, NBER Working Paper 13185.

Börsch-Supan, A., A. Ludwig, and J. Winter (2004), “Aging, Pension Reform, and Capital Flows: A Multi-Country Simulation Model”, Sonderforschungsbereich 504, Discussion Paper 04-61, University of Mannheim.

Börsch-Supan, A., and J.K. Winter (2001), “Population Ageing, Savings Behavior and Capital Markets”, NBER Working Paper 8561.

Bosworth, B., B. Burtless and J. Sabelhaus (1991), “The Decline in Saving: Some Microeconomic Evidence”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 183-241.

Brumberg, R., and F. Modigliani (1954), “Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data”, in K.K. Kurihara (ed.): Post-Keynesian Economics, pp. 388-436. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Canton, E., C. van Ewijk and P.J.G. Tang (2003), “Population Ageing and International Capital Flows”, European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes, Occasional Paper 4.

Chinn, M., and J. Frankel (2003), “The Euro Area and World Interest Rates”, Santa Cruz Department of Economics Working Paper 1031.

Cutler, D., J. Poterba, L. Scheiner and L. Summers (1990), “An Ageing Society: Opportunity or Challenge?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 112, pp. 1-55.

De La Croix, D., T. Lindh and B. Malmberg (2006), “Growth and Longevity from the Industrial Revolution to the Future of an Ageing Society”, Université Catholique de Louvain, Département des Sciences Economies Discussion Paper 2006-37.

De Santis, R.A., and M. Lührmann (2006), “On the Determinants of External Imbalances and Net International Portfolio Flows: a Global Perspective”, ECB Working Paper 651. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp651.pdf

De Serres, A., C. Giorno, P. Richardson, D. Turner and A. Vourc’h (1998), “The Macroeconomic Implications of Ageing in a Global Context”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper 193.

DellaVigna, S., and J.M. Pollet (2005), “Attention, Demographics, and the Stock Market”, NBER Working Paper 11211.

European Commission (2006), “The Impact of Ageing on Public Expenditure: Projections for the EU25 Member States on Pensions, Health care, Long-term care, Education and Unemployment Transfers (2004-2050)” European Economy Special Report 1/2006, February.

Ferrero, A. (2005), “Demographic Trends, Fiscal Policy and Trade Deficits”, Society for Economic Dynamics, Meeting Paper 444.

G10 (2005), “Ageing and Pension System Reform: Implications for Financial Markets and Economic Policies”. http://www.imf.org/external/np/g10/2005/pdf/092005.pdf.

Heijdra, B.J., and J.E. Ligthart (2006), “The Macroeconomic Dynamics of Demographic Shocks”, Macroeconomic Dynamics 10, pp. 349-370.

Hock, H., and D.N. Weil (2006), “The Dynamics of the Age Structure, Dependency and Consumption”, NBER Working Paper 12140.

Holzmann, R. (2005), “Demographic Alternatives for Ageing Industrial Countries: Increased Total Fertility Rate, Labor Force Participation, or Immigration”, IZA Discussion Paper 1885.

IMF (2004), “World Economic Outlook”, September.

Kara, E., and L. von Thadden (2006), “Monetary Policy and Demographic Changes”, European Central Bank, mimeo.

Lane, P.R., and G.M. Milesi-Feretti (2001), “Long-term Capital Movements”, NBER Working Paper 8366.

Laubach, T. (2003), “New Evidence on the Interest Rate Effects of Budget Deficits and Debt”, Finance and Economics Discussion Paper 2003-12. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Maddaloni, A., R. Musso, P. Rother, M. Ward-Warmedinger and T. Westermann (2006), “Implications of Demographic Developments in the Euro area”, ECB Occasional Paper 51. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp51.pdf

Medeiros, J. (2000), “Endogenous Versus Exogenous Growth Facing a Fertility Shock”, Université catholique de Louvain, Institut de Recherches Economiques et Sociales (IRES). Discussion Paper 2000017.

Meredith, G. (1995), “Demographic Change and Household Saving in Japan”, in Saving Behaviour and the Asset Price Bubble, IMF Occasional Paper 124.

Miles, D. (1999), “Modelling the Impact of Demographic Change upon the Economy”, Economic Journal 109, pp. 1-36.

Miles, D. (2002), “Should Monetary Policy Be Different in a Greyer World?”, in A. Auerbach and H. Herrmann (eds.), Financial Markets and Monetary Policy, pp. 243-276. Springer.

OECD (2005), “The Impact of Ageing on Demand, Factor Markets and Growth”, prepared for Working Party No. 1 on Macroeconomic and Structural Policy Analysis of the Economic Policy Committee.

OECD (2007), “Economic Outlook”, May.

Poterba, J.M. (2001), “Demographic Structure and Asset Returns”, Review of Economics and Statistics 83, pp. 565-584.

Poterba, J.M. (2004), “The Impact of Population Ageing on Financial Markets”, NBER Working Paper 10851.

Poterba, J.M., S.F. Venti and D.A. Wise (2007), “New Estimates of the Future Path of 401(k) Assets”, NBER Working Paper 13083.

Roeger, W. (2006), “Assessing the Budgetary Impact of Systemic Pension Reforms”, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_papers/2006/ecp248en.pdf, pp. 70-90.

Siegel, J. (1998), “Stocks for the Long Run”, McGraw Hill, 2nd ed. New York.

Weil, D.N. (2006), “Population Ageing”, NBER Working Paper 12147.

Yoo, P.S. (1994), “Age Dependent Portfolio Selection”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 94-003A.

Young, G. (2002), “The Implications of an Ageing Population for the UK Economy”, Bank of England Working Paper 159.

-

[1] I thank particularly Victor Lopez Perez for his major contribution to this text and Jean-Pierre Vidal for his comments.

-

[2] Fertility rates in the euro area were 2.8 for the period 1960-1965 and 1.5 for the period 2000-2005 (Maddaloni et al. ,2006).

-

[3] Life expectancy at birth in the euro area was 70 in the period 1960-1965 and 78 in the period 2000-2005 (Maddaloni et al., 2006).

-

[4] De Serres, Giorno, Richardson, Turner and Vourc’h (1998).

-

[5] European Commission (2006). Cutler, Poterba, Sheiner and Summers (1990) estimated that a 0.15% yearly increase in the rate of growth of productivity is needed to avoid a decline in living standards in the United States as a result of increasing dependency ratios.

-

[6] Bean (2004).

-

[7] Brumberg and Modigliani (1954).

-

[8] Meredith (1995). At the opposite end of the age structure, a 0.1 drop in the young-age dependency ratio would lead to an increase in the savings ratio of about 6.1 percentage points.

-

[9] A number of studies have looked into household data (surveys) to test whether individual saving behaviour is consistent with the life-cycle theory, and it is generally found that the savings rate of retirees does not fall as much as the life-cycle theory predicts. However, Miles (1999) clarifies that “the mistake here is to count all of pension receipts as income” as opposed to sales of their pension “rights”. Bosworth, Burtless and Sabelhaus (1991) compute the average savings rate for households over 64 years old in the United States, correcting for the pension adjustment suggested by Miles. While the unadjusted savings rate was 14.9%, the adjusted figure was only 1.8%.

-

[10] Miles (1999).

-

[11] Ferrero (2005) and Heijdra and Lightart (2006).

-

[12] See also Roeger (2006).

-

[13] Weil (2006).

-

[14] European Commission (2006).

-

[15] Canton, van Ewijk and Tang (2003). At the opposite end of the age structure, the European Commission (2006) estimates that the ratio of education expenditure over GDP in the euro area is likely to decline by around 0.6-0.7% over the next 50 years.

-

[16] The OECD (2007) estimates that, between 2005 and 2050, ageing in the euro area could increase public pension costs by 3% of GDP, public healthcare costs by 3.7%, and long-term care costs by 2.2%.

-

[17] Börsch-Supan, Ludwig and Winter (2004).

-

[18] Börsch-Supan, Ludwig and Winter (2004) predict that the number of employees as a percentage of the population in France, Germany and Italy as a whole will fall from current levels of slightly below 42% to below 36% by 2050.

-

[19] Miles (1999) obtains a decline of 50 basis points in the equilibrium real interest rate in the European Union, while internal results by Kara and von Thadden (2006) find a slightly steeper fall of around 90 basis points in the euro area. See also OECD (2005), Börsch-Supan, Ludwig and Winter (2004), Heijdra and Ligthart (2006), Canton et al (2003), and Young (2002). The hump-shaped macroeconomic response to post-Second World War demographic events was already anticipated by Auerbach, Kotlikoff, Hagemann and Nicoletti (1989).

-

[20] DellaVigna and Pollet (2005).

-

[21] Bakshi and Chen (1994).

-

[22] Miles (2002).

-

[23] Medeiros (2000) finds that ageing represents an opportunity for future generations to invest in education, since a shrinking labour force contributes to higher capital intensity ratios and thereby higher labour earnings, which boost the returns to human capital investments. De La Croix, Lindh and Malmberg (2006) point out that longer life expectancy raises the expected return from human capital investments and thus creates incentives to accumulate more education and training

-

[24] An exception is Becker, Murphy and Tamura (1990), who built a model that endogenises the human capital investment decision and also its link to fertility decisions. In their model, if the stock of physical capital is relatively large, the returns to education would become relatively attractive (higher expected real wages) and the cost of raising children would increase. See also Hock and Weil (2006) and Weil (2006).

-

[25] Chinn and Frankel (2003) found that US and European long-term real interest rates on government debt depended significantly upon current and expected levels of debt over the period 1973-2003. Laubach (2003) estimates that a 1% increase in the expected US debt-to-GDP ratio led to an average rise in US long-term rates of 5.3 basis points over the period 1985-2002. A different result is reported by Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1990), who analyse short-term real interest rates in Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States over the period 1959-1988, finding that fiscal variables are not significant either for the expected real interest rate or for the domestic investment/saving ratio.

-

[26] Canton et al (2003).

-

[27] Holzmann (2005) points out that, if the flow of immigrants does not accelerate, the combined total labour force in Europe, Russia, the high-income countries of East Asia and the Pacific, China, and North America may decline by around 5 million by 2025 and by 181 million by 2050. In order to keep the labour force constant in the EU25, around 1.5 million immigrants could be needed annually from 2005 to 2050

-

[28] De Serres et al (1998).

-

[29] Lane and Milesi-Feretti (2001). Batini, Callen and McKibbin (2006) find mild responses of the current account to demographic factors when they assume that developing countries cannot quickly absorb large amounts of foreign investment from developed economies: in Europe, ageing could contribute up to half a percentage point improvement in the current-account-over-GDP ratio from 2005 to 2025, but this effect turns slightly negative after 2030 (less than -0.2 percentage point). Börsch-Supan, Krueger and Ludwig (2007) simulate an open-economy model with free capital flows among OECD countries but no flows to non-OECD countries. They find that ageing will lead to a relative abundance of capital, with the real rate of return in the OECD countries falling by around 80-90 basis points between 2005 and 2050, and relatively modest capital flows from/to the European Union (current-account-over-GDP ratio of about 1% or less in absolute terms over the period 2000-2050).

-

[30] Economic theory suggests that capital should be flowing from developed economies, characterized by relatively older populations, higher capital endowments and fewer investment opportunities, to emerging market economies, where the population is younger, capital scarcer and investment opportunities relatively more abundant. Empirical evidence suggests that capital is not exactly moving in the expected direction. This could be attributed to a savings glut mainly originating in Asia, where demographic and institutional factors could also play a role. In a panel covering a large number of countries from 1970 to 2003, De Santis and Lührmann (2006) for example find that an increase in old-age dependency ratios has been correlated with capital inflows, challenging the view that ageing may contribute to current-account surpluses in developed countries. See also IMF (2004).

-

[31] Young (2002). Bean (2004) argues that longer life expectancy would presumably reinforce this effect. Poterba (2004) suggests that families whose head is over 65 years old will hold almost half of all corporate stock and 64% of all annuity contracts in the United States in 2040, up from 33% and 50% respectively in 2001. See also Poterba, Venti and Wise (2007).

-

[32] G10 (2005). Miles (2002) points out that the monetary policy multiplier would probably rise with population ageing, mainly as a result of the increased wealth channel and greater price impact of monetary policy decisions. However, he also mentions that an older population is less likely to be credit-constrained, especially when the pension system is reformed towards more funded systems. This might reduce the effectiveness of the credit channel. Depending on the relative importance of these channels, monetary policy could, in principle, become more or less effective with ageing. Miles suggests that the first effect is expected to dominate.

-

[33] Bakshi and Chen (1994) and De Santis and Lührmann (2006).

-

[34] G10 (2005) and Bean (2004).

-

[35] It is likely that, as a significant fraction of wealth is accumulated in real estate and financial assets, households’ exposure to asset price movements will tend to increase. This might coincide with a situation in which a large fraction of the population – in their old-age dissaving phase – are selling assets in order to finance consumption during retirement. In this respect, some authors have warned that, when the baby-boom generation retires and starts to dissave, excess supply in financial markets could contribute to a significant decline in asset prices, the consequences of which might be felt by the entire population (Siegel (1998), Abel (2001) and (2003), Börsch-Supan and Winter (2001), and Bean (2004)). This view is known as the “asset meltdown” hypothesis. Yoo (1994) estimated that asset prices may drop by as much as 15% as a result of demographic change alone. For a different viewpoint, see Young (2002) and Poterba (2001): according to Poterba (2004), relatively large swings in asset prices generated by changes in the demographic structure are very difficult to predict, because there has only been one baby-boom shock in the United States in the post-Second World War period. Hence, he argues that it seems risky to formulate predictions with only one data point in the sample.

Europese Centrale Bank

Directoraat-generaal Communicatie

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Duitsland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproductie is alleen toegestaan met bronvermelding.

Contactpersonen voor de media