The state of the housing market in the euro area

The state of the housing market in the euro area

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 7/2018.

The housing market has important macroeconomic and macroprudential implications for the euro area economy. In view of the duration of the ongoing upturn in euro area house prices and residential investment, which started at the end of 2013, analysing the state of the housing market is particularly informative. This article discusses the ongoing housing market upturn, from a chronological and fundamental perspective. It also explores a selected set of indicators that can potentially inform on the state of the housing market, elaborating on the demand and supply factors underpinning the current upturn, as well as their relative importance.

1 Introduction

Understanding and monitoring the state of the housing market is important because of its macroeconomic and macroprudential implications. Housing market developments affect investment and consumption decisions and can thus be a major determinant of the broader business cycle. They also have wealth and collateral effects and can thus play a key role in shaping the broader financial cycle. The housing market’s pivotal role in the business and financial cycles makes it a regular subject of monitoring and assessment for monetary policy and financial stability considerations.[1] This is especially relevant given that housing markets can be the source of booms and busts, with severe and long-lasting consequences for economic and financial development. Such episodes tend to reflect a decoupling of expectations over housing market tendencies from their fundamental determinants.

The housing market has a price and a volume dimension. Residential property prices (hereafter “house prices”) and residential investment are relevant dimensions and are the main focus of this article. They can be seen, in a broader context, as outcomes determined by the interaction of different supply and demand factors. Price and volume developments are not necessarily synchronised, so that possible misalignments between them can be an additional source of information. However, they can also make the overall assessment of the state of the housing market more challenging. For the euro area, this assessment is subject to the caveat that there is considerable heterogeneity across housing markets and their developments across countries. In addition, disentangling developments that could be associated with past boom/bust episodes, with a period of accommodative monetary policy or with changes in structural factors adds to the complexity of the analysis.

The state of the housing market is, by nature, unobservable but can be assessed from different perspectives. From a chronological perspective, the state of the market can be characterised by the length of its upturns or downturns, in particular, in comparison with the average durations of such phases. From a fundamental perspective, it can be assessed by the position of key indicators relative to benchmarks, for instance to determine possible house price overvaluation or unsustainably high activity in construction. The set of indicators that can potentially inform on the state of the housing market is large and the discussion in this article therefore needs to be selective.[2] It aims to distinguish broadly between demand and supply factors, although even this distinction may be difficult given the nature of some of the indicators.

Against this background, this article has two main sections. Section 2 puts into perspective the recent developments in house prices and residential investment in relation to the business cycle. Unless otherwise stated, these two indicators are expressed in nominal and real terms respectively. Section 3 elaborates on the demand and supply factors underpinning the current upturn in the housing market, as well as their relative importance.

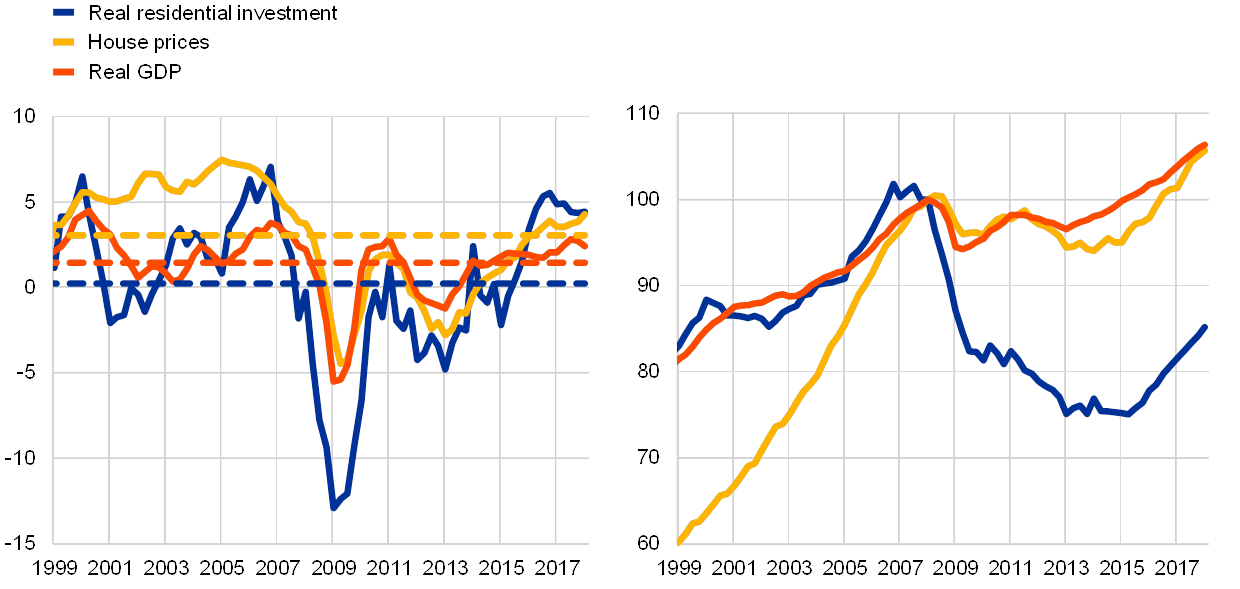

2 The state of the euro area housing sector: a look at residential investment and house prices

The upturn in the euro area housing market is in its fourth year. Measured in terms of annual growth rates, house prices started to pick up at the end of 2013, while the pick-up in residential investment started somewhat later, at the end of 2014. The latest available data (first quarter of 2018) indicate annual growth rates above their long-term averages (see Chart 1, left-hand panel) for both indicators. This is more evident for residential investment (where the upturn in growth rates has levelled off) than for house prices (where it has continued). The timing of the start of the upturn is broadly the same when measured in terms of the levels of the two indicators. At the same time, the level perspective highlights that residential investment is still considerably below earlier peaks, while house prices have recovered from the declines recorded during the financial crisis (see Chart 1, right-hand panel). In the aftermath of the financial crisis, residential investment declined sharply by 25%, bottoming out in 2014. Thus far it has only partially recovered and in early 2018 was still 15% below its pre-crisis level. House prices, on the other hand, contracted by only 6% between peak and trough, and in early 2018 were standing 5% above their pre-crisis level (although in real terms – deflated by the HICP – they were 5% below their pre-crisis level).

Chart 1

Residential investment, house prices and real GDP in the euro area

(left-hand panel: annual growth rates; right-hand panel: indices (Q1 2008=100))

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: Left-hand panel: long-term averages have been computed since the first quarter of1999 and are shown as dashed lines.

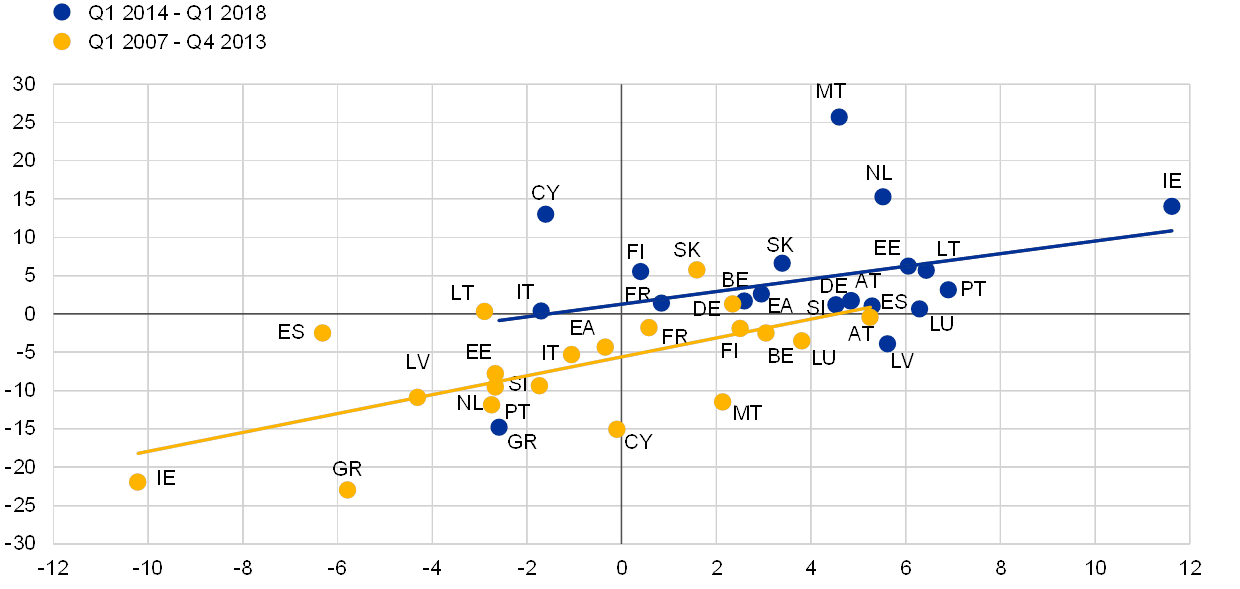

The upturn in the housing market is common to the majority of euro area countries. Over the last four years almost all of the countries have witnessed positive average growth in both residential investment and house prices, although with different magnitudes (see Chart 2). On balance, the majority of the countries share the feature, observed for the euro area as a whole, of concurrent growth in investment and house prices during the current upturn (blue dots), mirroring the relative adjustments in the preceding downturn (yellow dots). Some natural questions arise. How prolonged is the current housing market upturn compared with historical regularities? And, what can we expect going forward?

Chart 2

Residential investment and house prices during the most recent upturn and downturn

(x-axis: house prices; y-axis: real residential investment; annual average growth rates)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

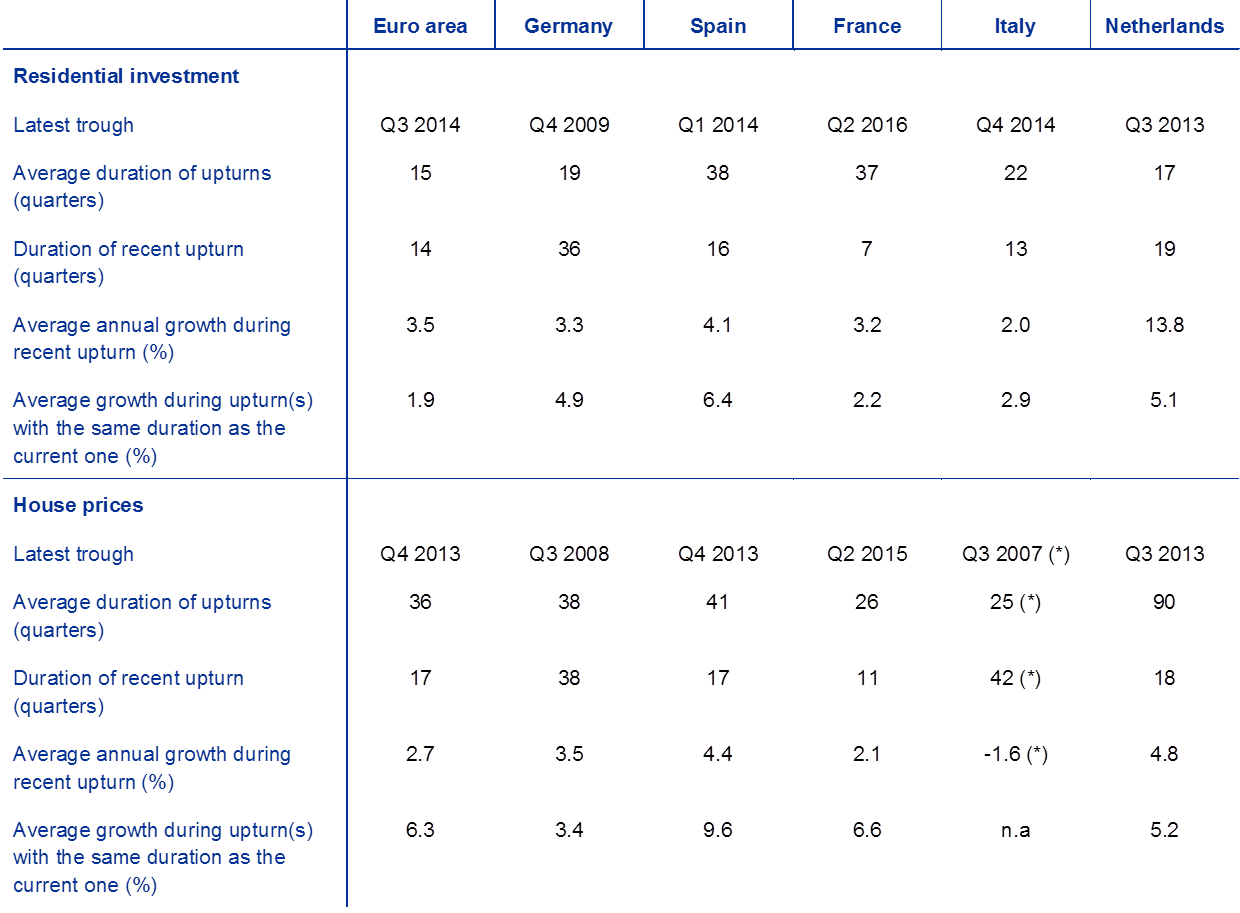

A turning point analysis suggests that the housing market upturn is in a relatively advanced phase compared with the average duration of such upturns. From a chronological perspective, at the aggregate euro area level, the length of the current upturn in both residential investment and house prices of about 4 years amounts to the average duration of historical upturns in residential investment and half the duration of historical upturns in house prices (see Table 1). For the purpose of this article, an upturn exceeding half the average duration of previous upturns shall be considered relatively mature. It should be borne in mind that turning point analysis is surrounded by considerable uncertainty, especially at the end of the sample, and that there is no unique way of dating the economic phases. Notwithstanding these caveats, if we consider the five largest euro area countries, the residential investment cycle has reached a mature phase in Germany and the Netherlands, while it is still at an early stage in France, Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain. According to this metric, the house price cycle is likewise advanced in Germany, while it is still at a rather preliminary stage in the other countries. In Italy, the formal turning point analysis does not yet suggest an upturn in house prices.[3] The maturity of the upturn can also be related to the strength of the recovery, with more mature cycles generally exhibiting lower rates of growth compared with those recorded at an early stage of the cycle.

The current euro area upturn is stronger than historical averages for residential investment but weaker for house prices. If cycles were to evolve around an unchanged trend, the relatively strong upturn in residential investment can be related to the relatively large fall in the aftermath of the crisis: during the ongoing upturn, euro area residential investment has increased at an annual average rate of 3.5%, clearly above the average of 1.9% recorded for the same duration in previous upturn phases (see Table 1). For euro area house prices, the corresponding comparison suggests a relatively muted upturn, with an annual average rate of increase of 2.7% – below the historical average of 6.3%. For house prices, this relatively muted pattern is common across the largest euro area countries, whereas in the case of residential investment the outcomes are mixed: the Netherlands and France exhibited higher than average upturns, while the opposite was true for Germany, Spain and Italy. This metric is an additional gauge for assessing the state of the housing market, but it comes with the caveat that the relative strength of the upturn may look “artificially” low in countries where the historical averages are influenced by unsustainable booms in the housing market. To this end, assessments against fundamental values are also needed.

Table 1

Turning points in the housing market: euro area and largest euro area countries

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The identification of upturns and downturns is based on real residential investment and real house prices (house prices deflated by HICP) using a modified Bry and Boschan (1971) quarterly algorithm (“BBQ”), as in Harding and Pagan (2002). The parameter of minimum phase duration set to six quarters, as in Borio and McGuire (2004) and Bracke (2011). Average growth denotes the annual rate of change of real residential investment and nominal house prices over the period Q1 1980‑Q1 2018. Only completed phases are included in the computation of average durations and growth rates.

(*) In Italy, where house prices have not yet bottomed out, data refer to downturn phases.

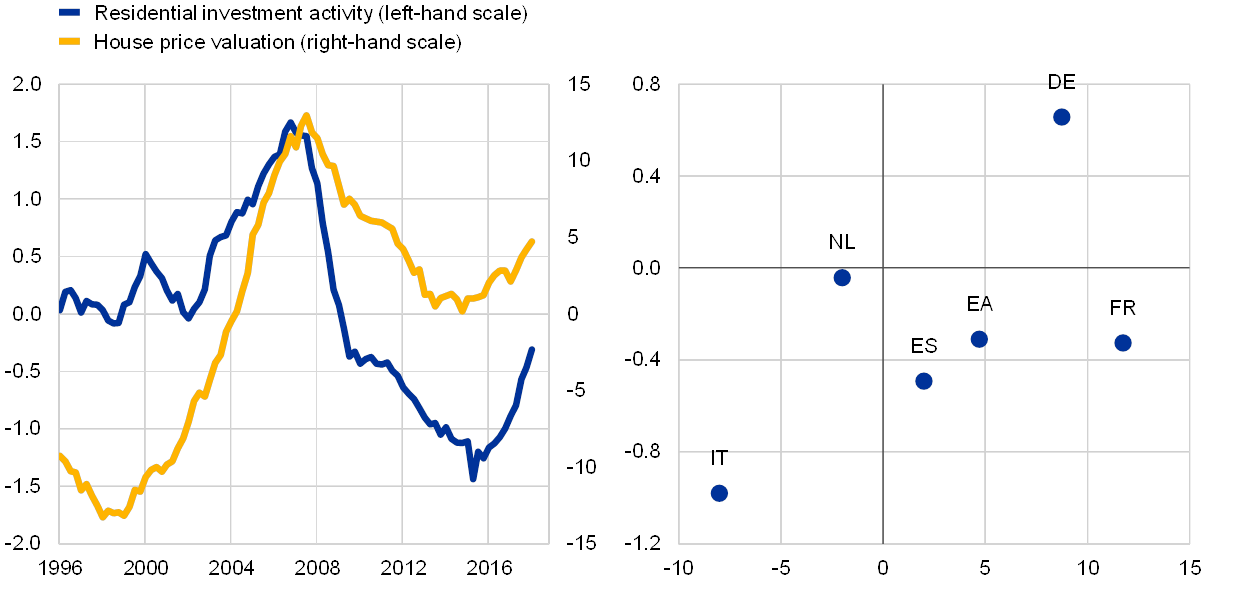

Assessing house prices and residential investment against fundamentals also provides insights on the state of the cycle. Chronologies of the housing cycle can only provide a partial gauge for assessing the state of the housing market, although, empirically, being out of tune with fundamentals often coincided with the state of the cycle being relatively more advanced and having seen a relatively strong magnitude of adjustment. Benchmarking against fundamentals can take several forms, such as simple ratios, deviations from model-explained values, or synthetic combinations of such metrics. In the case of house prices, valuation estimates are regularly applied in financial stability assessments[4] and currently point to a slight overvaluation for the euro area as a whole, as well as for Germany and France (see Chart 3). In the case of residential investment, this article introduces a synthetic indicator constructed from different (standardised) ratios for output and employment in the construction sector. For both the euro area and the largest euro area countries, this indicator suggests that the residential investment cycle is close to its historical norm, somewhat above for Germany and somewhat below in the case of Italy.

Chart 3

Benchmarking against fundamentals for residential investment activity and house prices

(left-hand panel: standardised index (left-hand scale); percentage points (right-hand scale); right-hand panel: x-axis: percentage points for house price valuation in Q1 2018; y-axis: standardised index for residential investment activity in Q1 2018)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB and staff calculations.

Notes: The synthetic indicator of residential investment activity is a simple average of four indicators (standardised so as to have zero mean and unit standard deviation since their earliest available date) and includes (1) residential investment as a share of GDP (both in nominal terms), (2) construction employment as a share of total employment, (3) labour shortages from the European Commission Survey on construction, and (4) building permits. A high level of the synthetic indicator may be interpreted as high residential investment compared with historical standards. The valuation estimates for residential property prices are based on four indicators: the price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios, a model-based estimate (Bayesian inverted demand model) and an asset pricing model. For further details, see Box 3 in the “Financial Stability Review”, ECB, June 2011, and Box 3 in the “Financial Stability Review”, ECB, November 2015.

Overall, the state of the euro area housing market is relatively mature but is not, so far, characterised by disproportionate residential investment activity or house price dynamics. The analysis shown in this section suggests more strength and maturity in the euro area residential investment cycle than in the house price cycle. However, measured against underlying fundamentals, the former does not appear, so far, to be above its historical norm. Given that the housing sector can be an important driver of the business cycle and that residential investment and house prices can have leading indicator properties for future economic activity, the current state does not herald imminent risks of a move towards a contraction in the economic cycle (see Box 1 for a more detailed analysis).

Box 1 The housing market as a predictor of prolonged contractions in economic activity

Fluctuations in the housing market are an important factor affecting business cycle dynamics and macroeconomic expectations.[5] While residential investment is a relatively small component of the economy (accounting, in nominal terms, for 6% of GDP between the first quarter of 1997 and the first quarter of 2018), it exhibits greater volatility than the other expenditure components of GDP. Residential investment is an expenditure component in its own right but can also have significant implications in terms of consumption expenditures in durable goods as new or refurbished housing is equipped. Housing-related decisions tend to be strongly correlated across households, since they are affected by aggregate variables such as demographic transitions and credit and financing conditions, thus acting as an important propagating mechanism of underlying shocks. Consequently, residential investment developments can have a wider impact on the economy. In particular, residential investment developments have been found to lead developments in GDP, especially before recessions.[6] In addition, house price developments have also been found to carry important information for subsequent recessions, especially when triggered by exuberant expectations and excessive credit growth. This box illustrates how residential investment and house prices can contribute to the estimation of short-term probabilities of future prolonged contractions in economic activity.

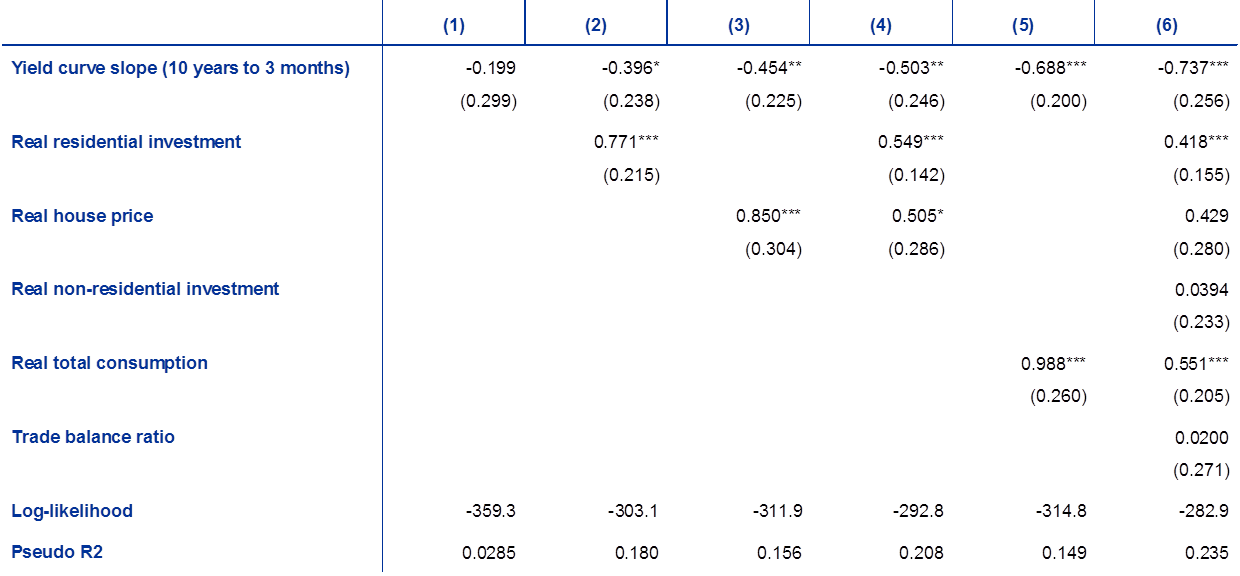

The specific hypothesis that housing market dynamics can predict prolonged contractions can be formally tested on the basis of a panel logit model on euro area data.[7] Following Kohlscheen et al. (2018),[8] the panel logit model regresses a binary indicator of a prolonged (at least two-quarter) contraction in real GDP occurring within the following four quarters on (1) the slope of the yield curve and (2) the number of quarters with a negative quarterly growth rate in the current and the previous three quarters of the two housing market indicators of interest.[9] In order to benchmark the predictive power of residential investment and house prices, the latter metric is also constructed for other GDP components: non-residential investment, total consumption and the trade balance.[10]

The model confirms a statistically significant predictive power of housing market variables for future prolonged contractions. All specifications in Table A confirm that the slope of the yield curve – except when considered alone in column (1) – provides useful information for forecasting the start of a prolonged contraction.[11] Columns (2) and (3) show that residential investment and house prices, respectively, significantly increase the predictive power of the model (from 3% to within 16‑18%, broadly in line with the estimates presented in Kohlscheen et al., 2018, with a similar model). Furthermore, as shown in column (4) of Table A, including both indicators at the same time further improves the predictive power (up to 21%). Columns (5) and (6) show that total consumption has a statistically significant predictive power both on its own (as do non-residential investment and the trade balance, which are not reported) and when all expenditure components are included in the model. The loss of statistical significance by house prices in the latter model may be due to the correlation of its information content with that of consumption, as house price declines may in turn weaken consumer confidence.[12]

Table A

Logistic regressions for the probability of a prolonged contraction starting within the following four quarters

(probability of the start of a prolonged contraction between t+1 and t+4 (log odds ratio))

Sources: Eurostat, OECD and ECB calculations.

Notes: The sample includes a balanced panel with observations over the period Q1 1997‑Q1 2017 for Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium and Finland. The dependent variable is a 0‑1 indicator, taking the value of 1 if a prolonged contraction (defined as a quarter belonging to a period of at least two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP quarterly growth) occurs at any time in the following four quarters (and 0 otherwise). All independent variables are computed as the number of quarters of the negative quarterly growth rate of the respective original variable in the current and the previous three quarters (except for the trade balance as a ratio of GDP, for which the quarter-on-quarter change is used in place of the growth rate), except for the slope of the yield curve, which is computed as the difference between the ten-year and the three‑month government bond yields. House prices are computed as the house price index divided by the overall HICP. The logit regressions are based on panel data estimation with fixed effects and standard errors clustered by country. Coefficients represent the log odds ratio. Standard errors are in parentheses. Asterisks denote the statistical significance of coefficients at the following confidence levels: *** 1%, ** 5% and * 10%. Coefficients for the constant and fixed effects are not reported.

Model specifications, including housing market variables, do not raise significant concerns about the viability of a continued economic expansion over the short term (see Chart A). The estimated parameters of the model specification, including the slope of the yield curve, residential investment and house prices (column (4) of Table A), are applied to euro area aggregate data between the first quarter of 1997 and the first quarter of 2018. It is then possible to generate fitted probabilities of four-quarter-ahead prolonged contractions until the first quarter of 2017 – to be compared with actual realisations of economic downturns – and forecast probabilities from the second quarter of 2017 to the first quarter of 2018 – to produce model-implied predictions. Compared with the 30% probability before the financial crisis started in 2008 and the 20% probability before the sovereign debt crisis started in 2011, the forecast probability of a prolonged contraction starting within the following four quarters is very low (about 3%) in the first quarter of 2018.[13] Importantly, both prolonged contractions observed over the past 20 years were preceded by model-implied probabilities of at least 20%, although probabilities of the same magnitude were observed that were not followed by contractions.

Overall, housing market variables significantly contribute to the prediction of imminent economic contractions beyond what can be inferred from the slope of the yield curve. At the same time, housing market variables alone cannot fully predict future economic contractions and other indicators, such as financial variables, may further improve on their predictive power. At the current juncture, the analysis presented in this box does not raise significant concerns of an imminent economic contraction as a result of housing market dynamics.

Chart A

Fitted and forecast probabilities of a prolonged contraction in the euro area starting within the following four quarters based on residential investment and house prices

(percentages)

Sources: Eurostat, OECD and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart reports the fitted and forecast probabilities of a prolonged contraction in the euro area starting within the following four quarters, based on the parameters estimated through the panel logit model, with residential investment and house prices for eight large euro area countries over the period Q1 1997‑Q1 2017, corresponding to column (3) of Table A. The fitted and forecast probabilities are then obtained by applying the estimated parameters to aggregate euro area data for Q1 1997‑Q1 2017 and Q2 2017‑Q1 2018 respectively. The shaded areas represent prolonged contractions, defined as periods of two or more consecutive quarters of negative quarterly real GDP growth.

3 Supply and demand factors behind the current state of the housing market

House prices and residential investment can be seen, in a broader context, as outcomes determined by the interaction of supply and demand factors. Such underlying factors can thus shed additional light on the state of the housing market. However, corresponding indicators are scarce, often lagging, and are not always easy to interpret in terms of whether they provide information unequivocally on the demand or the supply side. This section makes a selective approach to discussing some of these indicators.

3.1 Demand factors

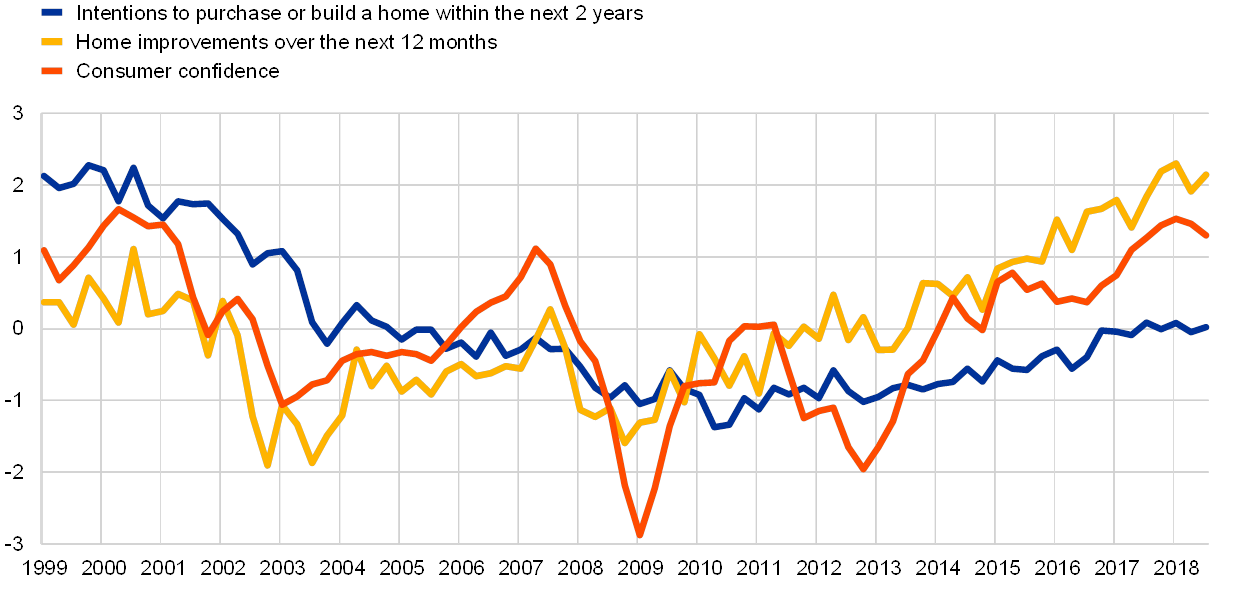

Consumer survey indicators point to ongoing increases in demand for housing. During the current upturn of the housing cycle, the number of respondents intending to carry out home improvements and to purchase or build a home has gradually increased in the euro area and in the vast majority of euro area countries (see Chart 4). The latest data thus suggest that further demand for housing – related to both the stock and the flow (investment) – may still be in the pipeline. For the euro area as a whole, the intention to carry out home improvements was close to an all-time high in mid‑2018, while the intention to purchase or build a home had increased more modestly and remained well below pre-crisis peaks. Since housing-related sentiment indicators have improved, on balance, more moderately than overall consumer confidence, data do not seem to point to a risk of exuberant demand. Intentions to purchase or build a home reflect a combination of cyclical and structural factors. Box 2 discusses homeownership as an example of the latter.

Chart 4

Euro area survey data as indicators of housing demand

(standardised percentage balances)

Sources: European Commission and ECB calculations.

Notes: Data are standardised so as to have zero mean and unit standard deviation from the first quarter of 1999.

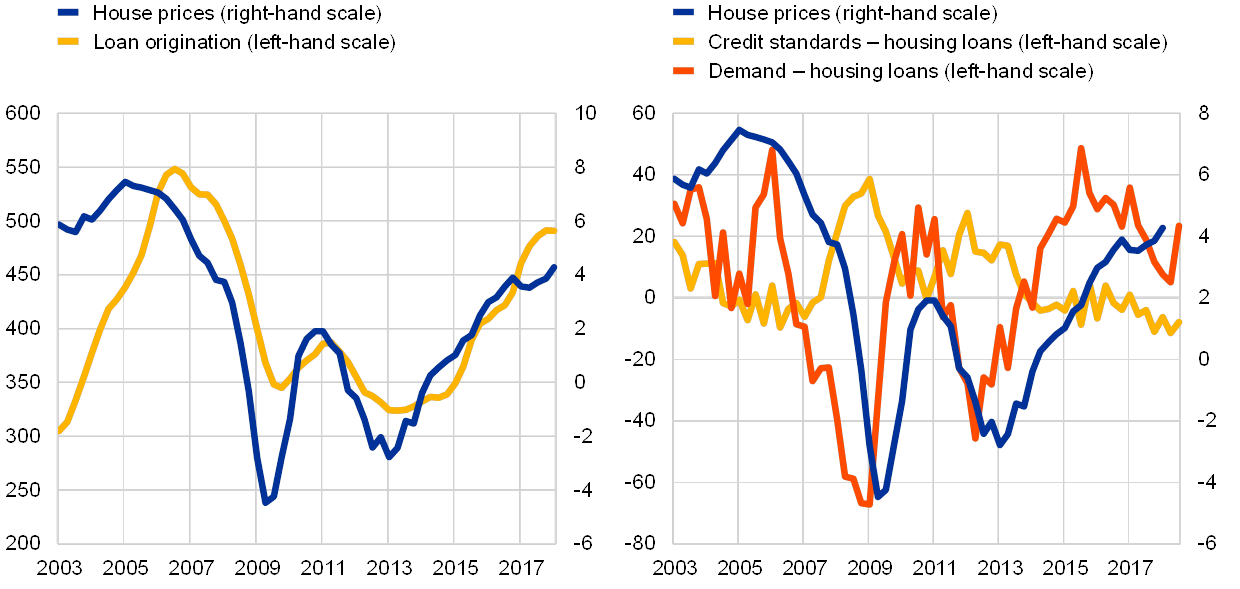

The rising demand for housing has been supported by developments in income and financing conditions. The current euro area housing upturn has been accompanied by an expansion in real disposable income. In addition, financing conditions remained favourable, as reflected in composite bank lending rates for house purchase that have declined by more than 130 basis points since 2013 and by easing credit standards. This has given rise to a higher demand for loans for house purchase and a substantial strengthening in new mortgage lending (see Chart 5). The expansion in loans for house purchases net of repayments has been rather moderate and thus suggests that the upturn in the housing market came with more moderate increases in mortgage indebtedness. However, gross loan origination suggests, at the same time, that the actual availability of credit for the purpose of purchasing and building houses is more than ample.[14] In this respect, the growth in mortgage loan origination in the euro area has been more synchronised with the growth in house prices. From a cross-country perspective, loan origination is currently at historical highs in Germany and France, close to its historical average in Italy, while it remains subdued in Spain.

Chart 5

House prices, loan origination, credit standards and demand for housing loans in the euro area

(left-hand panel: percentage changes, accumulated 12‑month flows in EUR billions; right-hand panel: percentage changes, net percentages)

Sources: ECB (euro area bank lending survey) calculations based on national data.

Notes: The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2018 for the bank lending survey (July 2018) and the first quarter of 2018 for loan origination and house prices.

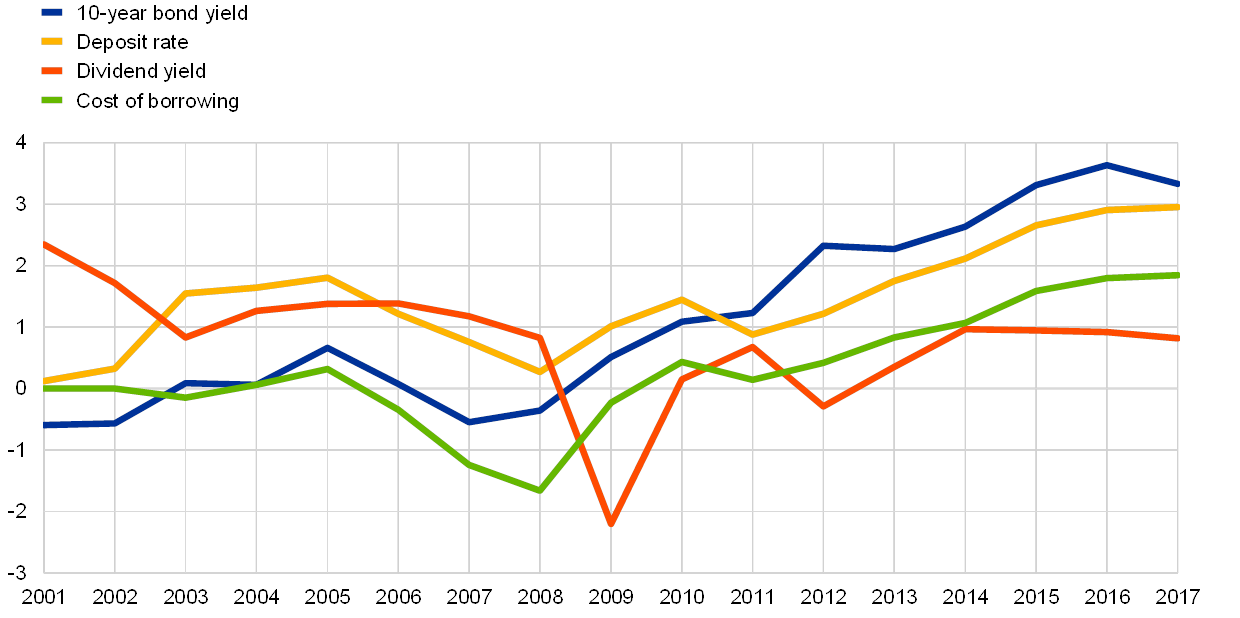

Housing demand is likely to have been supported also by investment motives. The relative attractiveness of housing as an investment class has increased during the recent housing upturn. Estimates of the return on housing-related investment are surrounded by considerable uncertainty but suggest an increase in the relative attractiveness of investment in residential property vis-à-vis alternative asset classes – such as government bonds, deposits and equities – since 2013 (see Chart 6).[15] Private and institutional investors, both domestically and globally based, searching for yield may thus have contributed to additional housing demand.[16] One expression of this search is portfolio reallocation and flows into real estate funds, which have increased steadily for the euro area as a whole since the beginning of 2013, also as a share of residential investment (see Chart 7). While too small in terms of size to account for substantial shifts in overall demand for real estate properties (some of which could also be directed to commercial real estate or outside the euro area jurisdictions), these funds can nevertheless indicate additional housing demand for investment purposes.

Chart 6

Return on housing-related investment in the euro area relative to alternative asset classes and to the cost of borrowing

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Eurostat, MSCI, DataStream, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart shows relative returns computed as the difference between the return on investment in housing-related assets and the returns on alternative asset classes (deposit, bonds and equities). The return on housing is computed as an average of two estimates: the gross rental yield and housing return. The deposit rate refers to deposits with agreed maturity over two years denominated in euro. The dividend yield represents the return on equity investments. The cost of borrowing refers to the composite lending rate for house purchases across different periods of interest rate fixation, weighted with a 24‑month moving average of new business volumes.

Chart 7

Flows into real estate funds

(12‑month flows in EUR billions; percentages)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB Investment Funds Balance Sheet Statistics and ECB calculations.

From a longer-term perspective, the positive cyclical factors of housing demand may have been dampened by structural factors such as demographics. Since 1995, the decreasing growth rate of the 20‑49 population age group, which is an important cohort in terms of housing demand, can contribute to explaining the declining residential investment share of GDP in the euro area and may have exacerbated the sharp cyclical fall in residential investment following the onset of the crisis (see Chart 8). Looking ahead, projections of growth in the euro area 20‑49 year-old population bracket suggest a bottoming out of this dampening structural factor in the coming years, leaving more room for ongoing positive cyclical forces to fuel demand for residential investment (as a share of GDP). Over a longer period of time, the relationship between the growth rate of the 20‑49 population age and residential investment is also observed at the country level.[17]

Chart 8

Population growth and residential investment in the euro area

(percentage points, annual average)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: From 2018 onwards, growth in the 20‑49 year-old population bracket is based on Eurostat projections. The ratio of residential investment to GDP is measured in real terms.

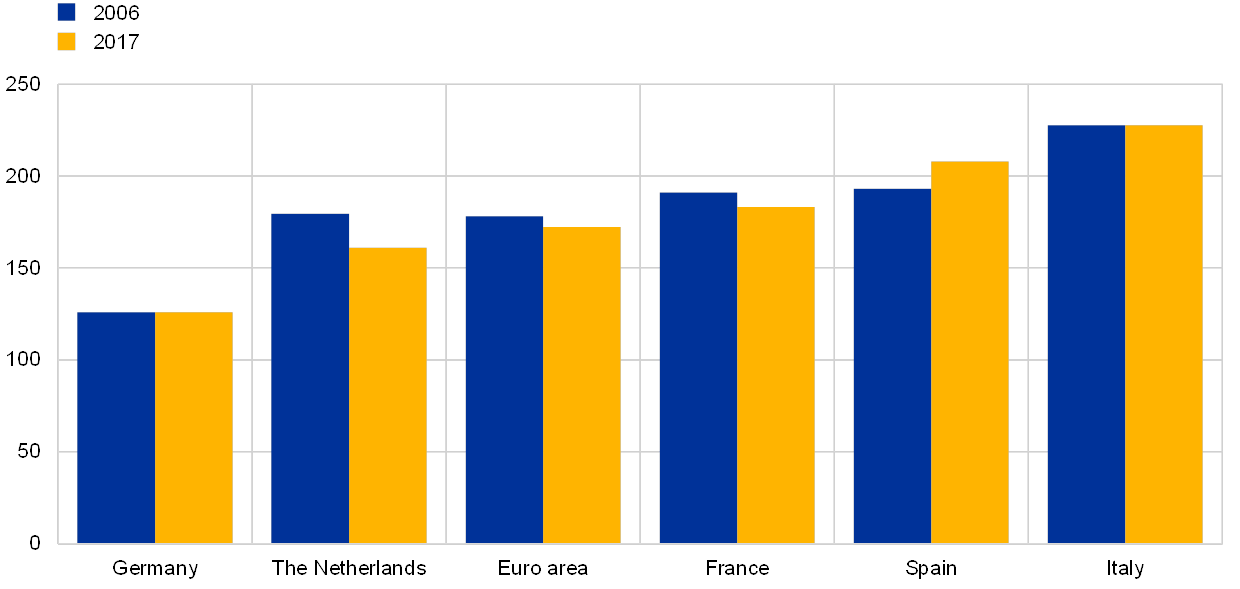

Box 2 Explaining homeownership ratios making use of micro data

The degree of homeownership can be a structural factor determining housing demand and thus house price dynamics. For instance, wealth effects associated with owning a house can stimulate economic growth and thereby house prices. Moreover, homeowners can use capital gains to “trade up” in the housing market, thus enhancing house price dynamics. The higher the homeownership ratio, the more potential there may be for increasing the dynamics, volatility and excessiveness of house price dynamics. An indicative although causally not exhausting relationship is that existing between the level of the homeownership ratio and the average growth in house prices across euro area countries (see Chart A).This box investigates the main determinants of homeownership making use of micro data.

Chart A

Nominal house price changes and homeownership ratio across countries

(x-axis: homeownership ratio in 2016; y-axis: annual average of nominal house price changes over the period 2000‑17)

Sources: EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU‑SILC) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Changes in homeownership appear to be a slow-moving process: from 2010 to 2016, the ownership rate decreased from 66.8% to 66.4% at the euro area level. Thus, looking only at the level of ownership appears to be still meaningful.

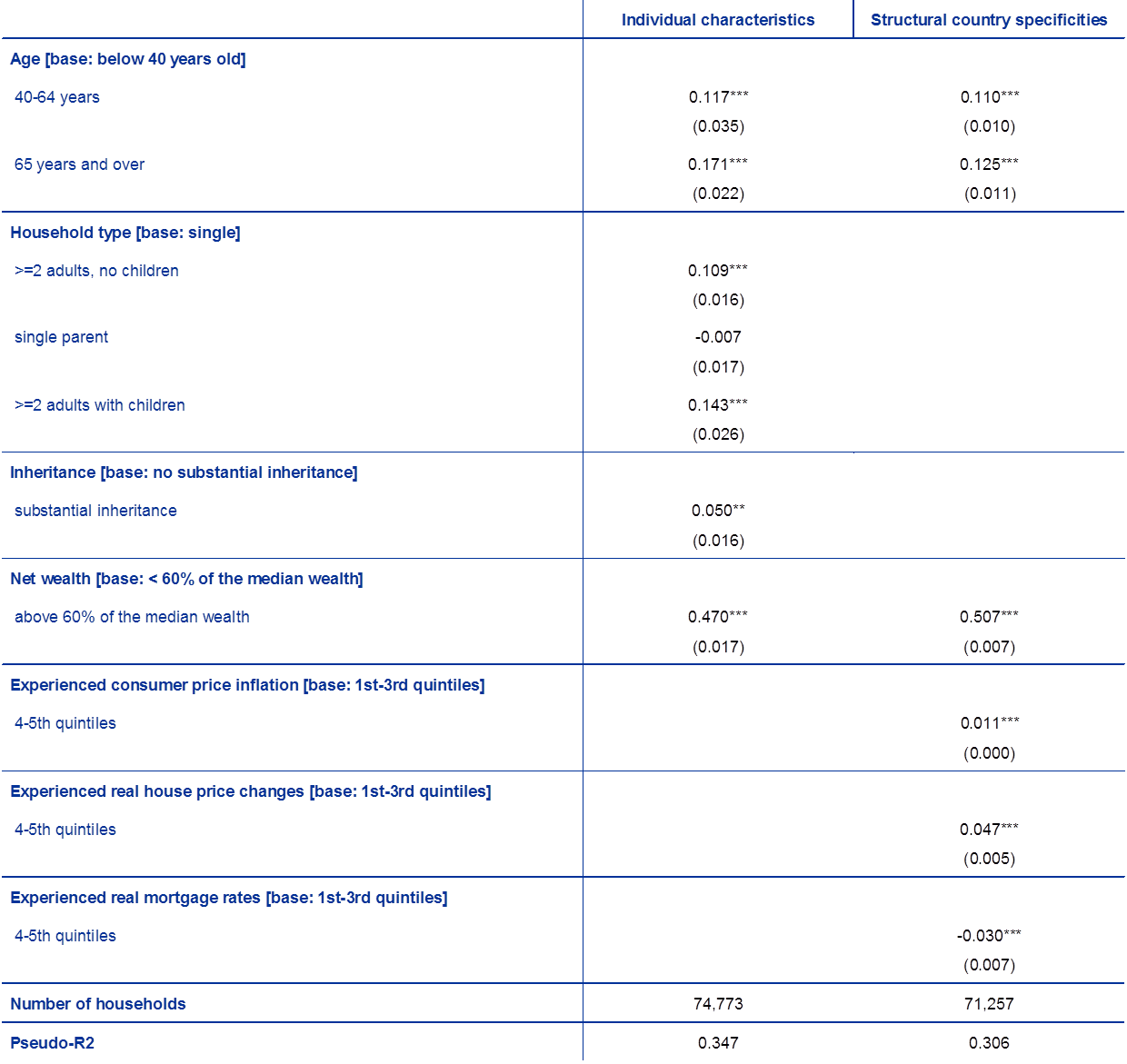

Results of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey indicate that both household-specific and structural characteristics are important drivers of homeownership.[18] They indicate that the probability of owning the main residence is positively linked to the age of the households, to having previously received inheritances, to being married and having children, and to net wealth. In addition, households that experienced higher aggregate consumer price inflation in the past are more likely to own their home. This also holds when considering aggregate house price inflation and can be reconciled with a desire to hedge against inflation and acquire real assets. Furthermore, low real mortgage interest rates experienced in the past are also a driver of ownership, but only among households that experienced the highest cost of borrowing. All in all, these results are broadly consistent with findings in the literature.[19]

Overall, micro data can be usefully employed in the analysis of housing developments, as they provide complementary information to macro data. This is typically the case the more house price dynamics have been affected by structural factors. While conjunctural factors can be sufficiently assessed with aggregate indicators, as presented in Sections 2 and 3 of this article, structural characteristics are better explored on the basis of micro data. Among the structural characteristics of the housing market is homeownership, a preference that is important to understand for assessing housing market prospects. In the coming years, as the population gets older and past experiences of macroeconomic conditions move over time, shifts in ownership across countries might occur, spawning effects on housing markets.

Table A

Average marginal effects from a probit regression of homeownership across euro area countries

(marginal probability of being the owner of main residence, compared with a baseline [explained in brackets])

Sources: Household Finance and Consumption Network 2016 and ECB calculations, based on 18 out of 19 euro area countries. Data for Lithuania are missing.

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Asterisks denote statistical significance of coefficients at the following levels: *** 1%, ** 5% and * 10%. Regressions are carried out at the household level and include country fixed effects for which the estimates are not reported. Age corresponds to the age of the reference person in the household. Based on this age and on the date of interview, one reconstructs the experienced inflation, real house prices, mortgage rates, regulation and tax regime over the life of each household. Households are finally clustered into quintiles, determined by the degree of past average experiences for the different variables. The average marginal effect gives the effect on the probability of the change in explanatory variables: on the top line of the table under Age, 0.117 means that the probability of owning a house increases by 0.117 for the 40‑64 year-old cohort compared with those less than 40 years old.

3.2 Supply factors

This section analyses how the volume of houses has evolved in recent years and the extent to which there are factors which constrain housing supply.

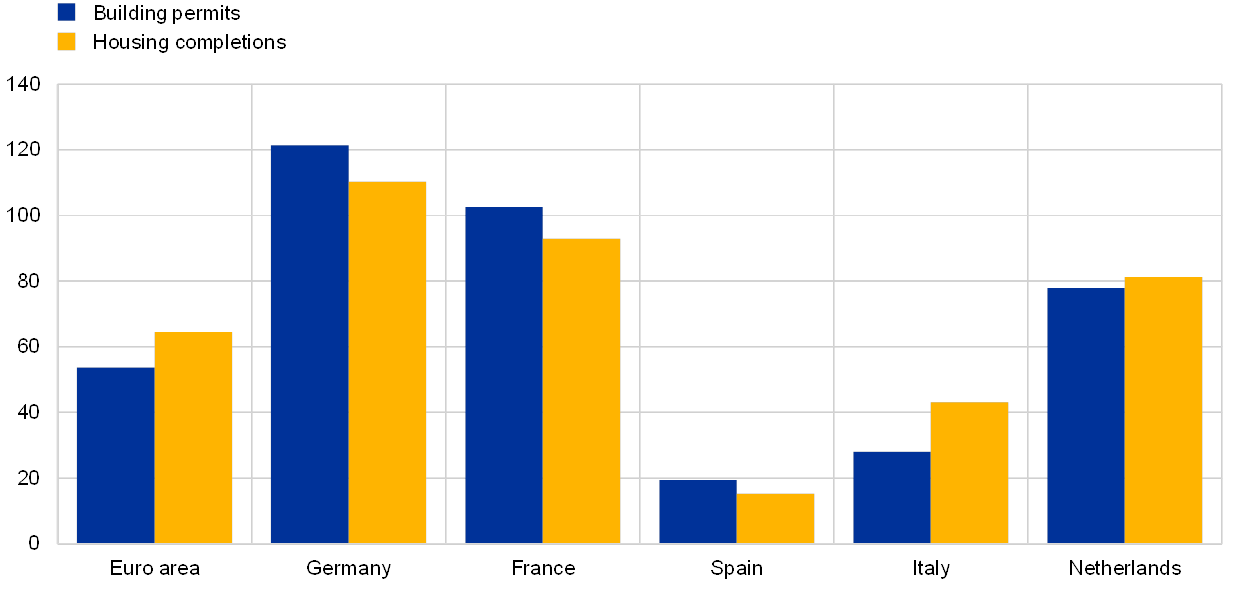

Housing completions in the euro area have remained substantially below their average level since the start of monetary union. This indicator can be viewed as a measure of the flow of new houses supplied to the market. In Germany and France this flow has recently been close to the average levels observed since the start of monetary union, whereas in Spain, Italy and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands it has remained subdued (see Chart 9). At the same time, the granting of building permits, which are a necessary – but not sufficient – condition to building a house, has increased more strongly than housing completions in a number of large euro area countries. Since it appears that the supply constraints from a lack of building permits have been easing, increases in residential investment activity and new housing supply may be forthcoming.

Chart 9

Housing completions and building permits in the euro area and large euro area countries: latest available data

(index: 1999‑2017 average = 100)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: Owing to a lack of recent data on housing completions, for the sake of comparability within countries both building permits and housing completions refer to the same year in each country, specifically 2017 for Germany and Spain and 2016 for the other countries and the euro area aggregate.

The lack of building permits can be a constraint to housing supply. In central locations and cities, especially, the number of issued permits may fall short of actual demand due to the scarcity of building land. A relatively low number of permits then pose a constraint on the supply of new homes. In central locations, where the availability of land is limited, the competition for scarce building permits may be aggravated by demand from investors interested in building commercial real estate, and who – according to anecdotal evidence – currently seem to have a preference for urban areas. However, data limitations prevent firm conclusions from being drawn.[20] The notion of local supply constraints is supported by a stronger increase in house prices in capital cities vis-à-vis the corresponding countries’ average in the current housing market upturn.[21]

In the shorter term, housing supply can also be constrained by the time required to receive permits. Administrative restrictions – such as the time required to obtain a building permit – are a major factor affecting the elasticity of housing supply in reaction to demand.[22] Consequently, when demand for housing picks up, one would expect it to show initially in a relatively larger rise in house prices than in quantities, as measured by residential investment. To illustrate this point, in 2017 a construction company needed roughly 126 days to obtain a building permit in Germany, compared with 228 days in Italy and 208 days in Spain (see Chart 10).

Chart 10

Number of days to obtain a building permit in the euro area and in the large euro area countries

Sources: World Bank’s “Doing Business 2018 – Reforming to create jobs” and ECB.

Note: The euro area aggregate is a weighted average (using GDP weights) of 18 euro area countries (data for Malta are not available).

Another factor that may have limited housing supply is a shortage of labour in construction production. Survey data on the percentage of construction firms signalling constraints on production due to a lack of workers suggest that labour shortages have started to become an issue in the current housing market upturn. The percentage of companies reporting labour as a factor limiting production recorded a fourfold increase in the euro area over the past three years, from almost 5% in the third quarter of 2015 to more than 20% in the third quarter of 2018 (see Chart 11). Among the five largest euro area economies, these developments were more accentuated in Germany, France and the Netherlands.

Chart 11

Labour as a factor limiting construction production in the euro area and in the large euro area countries

(percentage of respondents; seasonally adjusted)

Source: European Commission’s (DG‑ECFIN) Construction Survey.

Notes: A number of the observations are negative due to seasonal adjustment of the data. These observations are shown to illustrate the true evolution of labour shortages.

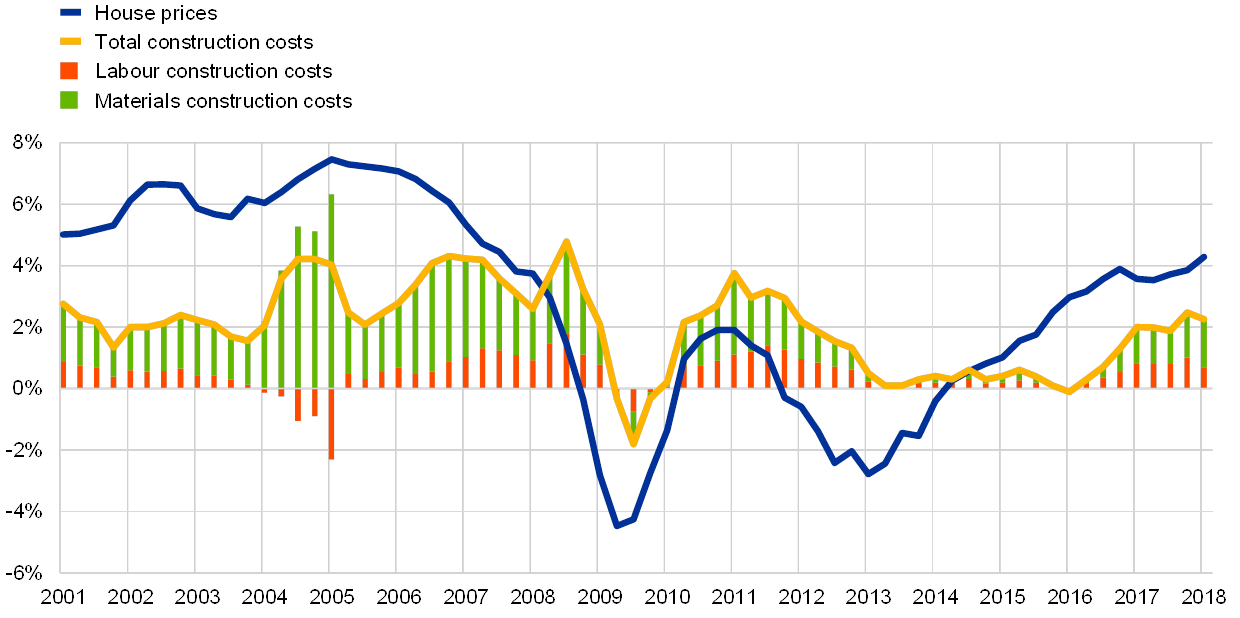

Labour shortages may affect the prices in the housing market in different ways. On the one hand, shortages may lead to gradually higher wages in the construction sector, which, in a situation of sufficient demand, will then be passed through to construction output prices. On the other hand, shortages may constrain or delay the supply of new houses in relation to demand and then imply a rise in house prices that does not necessarily come with higher construction output prices. Thus far, the marked rise in construction costs since 2014 has been increasingly fuelled by rising labour costs (despite their lower weight in the overall index), indicating growing labour shortages, and has been accompanied by strong momentum in house price growth, signalling buoyant demand (see Chart 12).

Chart 12

House prices and construction costs

(year-on-year percentage changes and percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The construction cost index refers to new residential buildings excluding residences for communities. Materials construction costs capture all non-labour construction costs, including materials (which are typically the largest part), as well as architectural, legal and other fees.

3.3 The relative importance of housing demand and supply

Assessing the relative importance of housing demand and supply factors is intrinsically challenging, as data mainly refer to equilibrium outcomes. For example, rising house prices may reflect an increase in demand for housing or a reduced supply of houses. With this caveat in mind, this subsection reviews available survey evidence and model-based results to assess the relative contribution of supply and demand factors to the state of euro area housing markets.

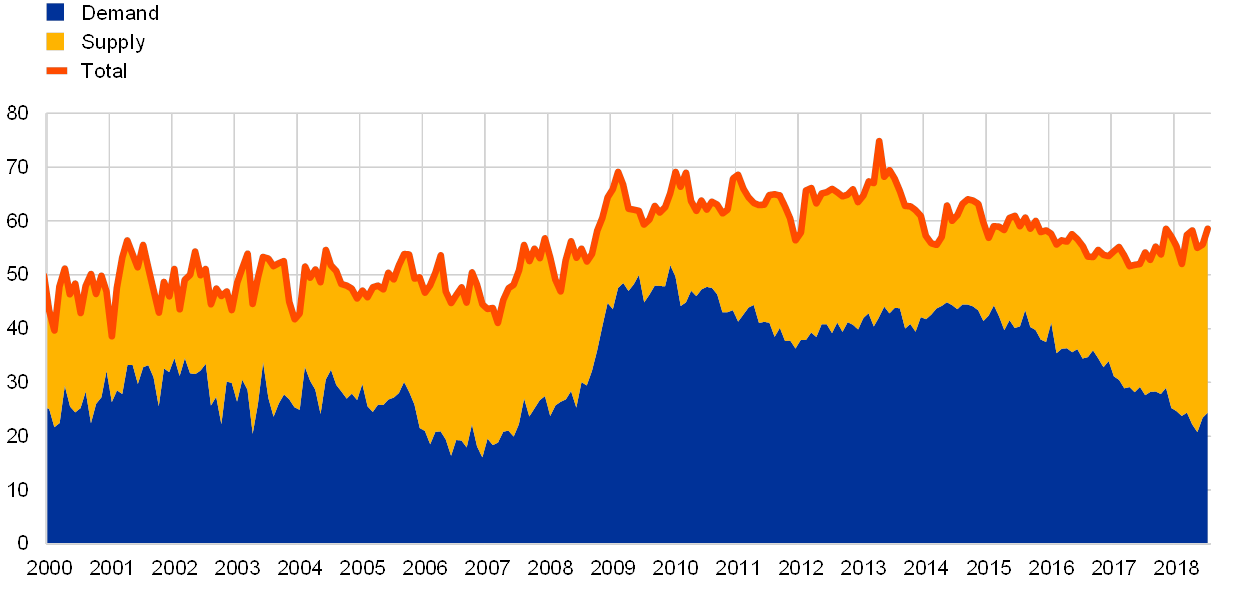

Survey data point to an increasing relative importance of supply factors in determining the dynamics of prices and investment in the housing market. The proportion of construction firms[23] indicating constraints to their production has hovered between 50% and 60% since 2014. However, the composition between reported demand-side and supply-side constraints has varied significantly: the share of firms reporting insufficient demand as a factor limiting production has decreased substantially, with opposite developments for firms reporting supply-side constraints (see Chart 13). Recently, there has been approximately a 10‑percentage point increase in the number of respondents noting supply-side rather than demand-side constraints limiting production. This suggests that constraints on construction producers’ output have recently mainly come from the supply side. This evidence is confirmed through the lenses of a stylised model with residential investment and house prices (see Box 3).

Chart 13

Factors limiting construction production in the euro area

(percentage of respondents, seasonally adjusted)

Sources: European Commission’s (DG‑ECFIN) Construction Survey.

Notes: Demand refers to the percentage of respondents noting insufficient demand as a factor limiting production. Supply refers to the percentage of respondents reporting neither insufficient demand nor no constraints (i.e. one hundred minus the percentage of respondents reporting no constraints minus the percentage of respondents reporting insufficient demand).

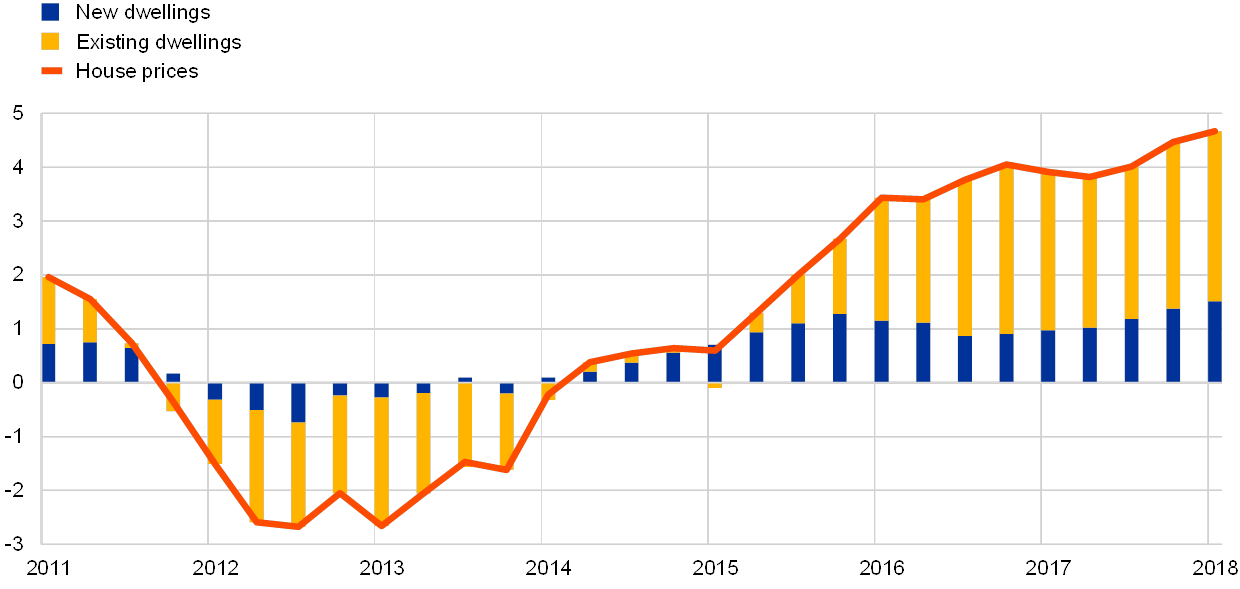

The relative importance of housing demand and supply factors can also be assessed by means of information concerning the composition of house prices. The more demand outpaces supply, the more prices of existing dwellings should be expected to rise as the competition for housing extends to existing properties. Whether the prices of existing dwellings rise faster than those of new dwellings also naturally depends on whether there are bottlenecks in the supply of new dwellings and on the responsiveness of construction output prices. It is thus conceivable that the prices of existing dwellings reach a larger amplitude at the peaks of the cycle compared with the prices of new dwellings. Indeed, over recent years, the contribution of prices of existing dwellings to overall house price growth has risen sharply, from close to 10% at the start of the upturn in 2014 to almost 80% in 2016, hovering above 70% – but on a declining path – over the last year (see Chart 14). At the same time, the increase in the contribution of prices of new dwellings since late 2016 (although still subdued) may confirm a tightening housing market, with increasingly binding supply-side constraints: amid buoyant housing demand, new dwellings cannot be provided fast enough and their prices tend to rise more rapidly.

Chart 14

Decomposition of house price growth by type of dwelling

(year-on-year growth rates and percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

The analysis presented in this section suggests an increasing role for supply-side constraints in determining dynamics in the euro area housing market. During the early stage of the upturn, a significant positive adjustment in residential investment was accompanied by relatively smaller house price increases. Over the most recent quarters, as the upturn in the housing market continues, buoyant demand amid increasing supply constraints has been associated with moderating residential investment growth and continued rising growth in house prices.

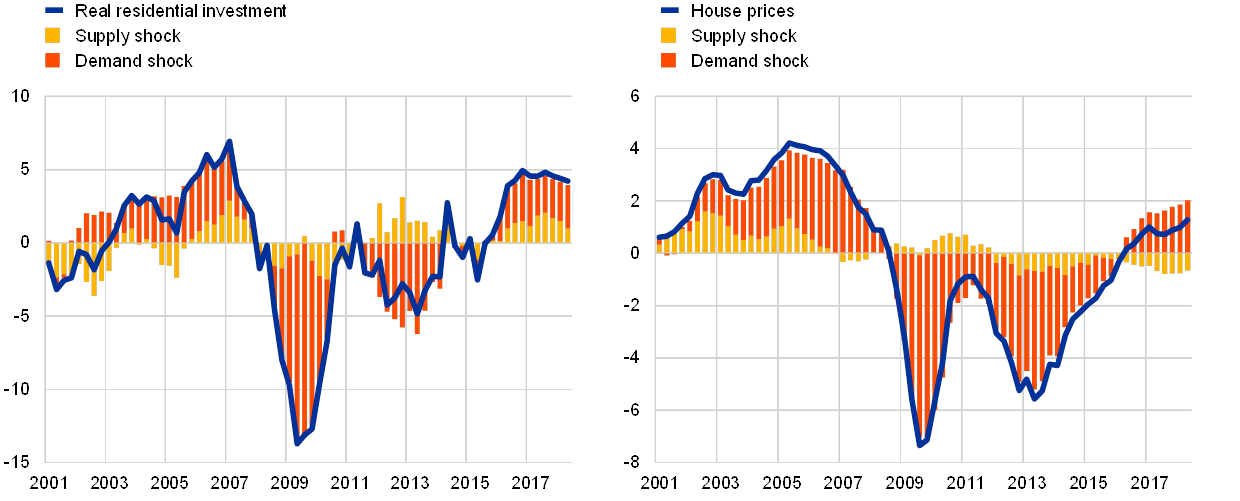

Box 3 The relative importance of demand and supply factors in driving housing market developments

Individual indicators of demand and supply factors can be inconclusive about their relative importance in driving residential investment and house prices. This relative importance can be better captured, assessed and quantified through the lenses of economic models. This box presents a rather stylised, two-variable Bayesian Vector Auto-Regression (BVAR) model with residential investment and house prices. The relative importance of supply and demand factors is assessed by identifying demand and supply shocks and by measuring their relative contribution in driving fluctuations in these two variables. This practice – typically referred to as historical decomposition – is rather standard in the empirical economics literature. Shocks are identified by imposing (sign) restrictions to the reaction of the underlying variables in response to these shocks: a demand shock leads to a positive co-movement between residential investment and house prices, and a supply shock to a negative co-movement.[24] Naturally, this identification restriction is rather general and encompasses a rather broad range of “demand shocks” and “supply shocks” but illustrates a possibility to disentangle supply and demand “forces”, broadly defined.[25]

In the interpretation of the model, demand is the main driver of aggregate movements in the housing market. The relative importance can be assessed in terms of “forecast error variance decomposition”, where demand shocks explain approximately 65% of the movements in residential investment and as much as 80% of those in house prices.

Consistent with the overall dominance of demand factors in driving the housing cycle, model evidence suggests that demand buoyancy has more than compensated for lacklustre supply in the housing sector over the last few years. On the volume side, residential investment growth has been growing positively and above average since the third quarter of 2015. According to the BVAR model, during this period residential investment growth has been supported by both supply and demand shocks, turning positive following a long period of subdued demand that dates back to the Great Recession (see Chart A, left-hand panel). On the price side, house prices have been increasing above average since 2016. As with the volume side, this reflects primarily a strong positive contribution from demand factors, which turned positive, having persistently contributed to lower house prices since the second quarter of 2008 (see Chart A, right-hand panel). Strong demand over this period has outweighed positive supply-side developments that have otherwise contributed to lower house-price growth. Finally, focusing on developments over this last year, the relative contribution of supply factors to both residential investment and house-price growth has been steadily decreasing, whereas the relative importance of demand factors has increased. This evidence is consistent with the presence of increasing supply-side bottlenecks and demand-side momentum behind the expansion of the housing cycle at the current juncture.

Chart A

Historical decomposition of residential investment and house prices between supply and demand shocks

(annual growth rates)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Supply and demand shocks refer to shocks to euro area real residential investment and house prices identified through sign restrictions in a Bayesian Vector Auto-Regression (BVAR) model with four lags and Minnesota priors. The series are demeaned. The house price series is seasonally adjusted.

4 Conclusions

The euro area housing market has been in an upturn since the end of 2013 and is in a relatively advanced state of the cycle in terms of duration. House prices have surpassed their pre-crisis peaks, while residential investment is still significantly below. The state of the euro area housing market is, so far, not characterised by generalised investment activity or house price levels above their fundamentals. However, considerable heterogeneity in developments across and within countries makes the overall assessment more challenging.

The housing market upturn is expected to continue but at a more moderate pace. This reflects expectations in currently available forecasts and projections that the euro area economic expansion will continue, reflecting the favourable impact of the very accommodative stance of monetary policy, improving labour market conditions and stronger balance sheets. This context generates income and financing conditions conducive to housing demand. Lending to households for house purchase is also expected to remain dynamic in the coming years. Nevertheless, in line with the expected slowdown in the pace of economic activity, the rate of expansion in the housing market is also expected to moderate. A moderation in residential investment might also emerge from the increasing presence of supply-side constraints in some euro area countries, which may currently be more binding than in the respective economies as a whole. These constraints could however mitigate the envisaged moderation in house prices.

Monitoring a broad set of housing-related indicators is key to assessing the macroeconomic and macroprudential implications of the housing market. To fully assess the state of the housing market it is necessary to look at both the major demand and supply determinants and their interactions. Moreover, given the extended interactions between real and financial variables, a broader set of indicators – some of which were discussed in this article – that goes beyond house prices and residential investment (such as loan developments, house price valuation, household balance sheets, etc.) should be continuously monitored to fully understand the macroeconomic and macroprudential implications of the ongoing housing upturn.

- For an earlier discussion, see the article entitled “The state of the house price cycle in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2015.

- In this respect, the article does not discuss some indicators that regularly feature in other assessments of the housing market, such as household balance sheet positions. For additional indicators see, for instance, “Methodologies for the Assessment of Real Estate Vulnerabilities and Macroprudential Policies – Residential Real Estate”, ESRB, forthcoming.

- A visual inspection of the series would instead suggest a trough around the first quarter of 2015, after which house prices have been broadly stable.

- Valuation estimates are surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty, while their interpretation may be complicated at the country level, given national specificities like fiscal treatment or structural factors (e.g. tenure status). Moreover, developments are heterogeneous not only across countries but in some cases across regions within a country. For further discussion, see “Financial Stability Review”, ECB, May 2018 and “Monthly Report”, Deutsche Bundesbank, February 2018.

- For a comprehensive overview of the literature on housing and business cycles, see Piazzesi, M. and Schneider, M., “Housing and Macroeconomics”, Handbook of Macroeconomics, Vol. 2B, 2016.

- For evidence of the predictive power of residential investment for recessions in the United States, see Leamer, E.E., “Housing really is the business cycle: What survives the lessons of 2008‑09?”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Supplement to Vol. 47, No 1, 2015.

- The sample includes a panel of eight large countries between the first quarter of 1997 and the first quarter of 2017. The selection of the countries aimed to identify economically significant estimates from a euro area perspective over the last 20 years, thus excluding relatively small countries joining the euro area in the late 2000s and (former) programme countries (Ireland, Greece and Portugal). Results for housing variables (investment and prices) are robust to the inclusion of the latter countries.

- Kohlscheen, E., Mehrota, A. and Mihailjek, D., “Residential investment and its role in economic activity: Evidence from the past five decades”, BIS Working Papers, No 726, 2018.

- Several studies have found the yield curve to be the best single predictor of recessions (e.g. Rudebusch, G. and Williams, J., “Forecasting recessions: the puzzle of the enduring power of the yield curve”, Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, Vol. 27, 2009, pp. 492‑503). However, more recent evidence has questioned the power of the slope of the yield curve as a predictor of prolonged contractions, due to a decoupling of future short-term interest rates from their expected path (e.g. Schrimpf, A. and Wang, Q., “A reappraisal of the leading indicator properties of the yield curve under structural instability,” International Journal of Forecasting, Vol. 26, 2010, pp. 836‑857). These deviations may have stemmed from default risk – leading to the steepening of the yield curve before a prolonged contraction – and the ensuing implementation of unconventional monetary policies – leading to the flattening of the yield curve before a recovery.

- Endogeneity is then partially taken into account by the lag difference between the dependent variable and the independent variables.

- The lack of significance of the slope of the yield curve as a single predictor in column (1) may be due to an omitted variable bias, which is then (at least partially) addressed by the introduction of further regressors.

- See, e.g. Campbell, J. and Cocco, J., “How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 54, 2007, pp. 591‑621.

- Compared with results from only housing market variables, introducing all variables – as in the model reported in column (7) of Table A – would produce comparable results, yielding a lower probability of a prolonged contraction (about 30%) before the second quarter of 2008, a higher probability (again, about 30%) before the fourth quarter of 2011 and a broadly similar probability in the first quarter of 2018 (about 2%).

- For a discussion, see the box entitled “Developments in mortgage loan origination in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2018.

- The first estimate – the gross rental yield – is computed as the ratio of actual and imputed rents over the gross housing capital stock and is meant to be a broad, macroeconomic measure of rental yield. The second estimate of housing return is from the MSCI Quarterly Research Database and reflects residential property portfolios for institutional investors. These portfolios are likely to invest predominantly in the prime or close-to-prime market, a sector which is likely to have a different dynamic from the entire residential market; this estimate is therefore narrower in scope.

- See Chapter 3 of the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report, April 2018, documenting an increase in real estate investments by private equity firms and real estate investment trusts in advanced economies. This is also supported by the considerable increase in the size of the professionally managed real estate investment market globally and in several euro area countries in 2017, with the German market replacing China as the fourth largest market globally. For a discussion, see “Real Estate Market Size 2017”, MSCI, June 2018.

- Monnet, E., and Wolf, C., “Demographic Cycle, Migration and Housing Investment”, Journal of Housing Economics, Vol. 38, 2017, pp. 38‑49. At the euro area level, data are only available from 1995, while Monnet and Wolf (2017) carried out estimations at the country level from 1980. Highlighting the strong cyclicality of the 20‑49 year-old population growth rate, they show that housing demand is better measured when looking only at the evolution of the age group relevant for household formation, all other age groups being held constant.

- The Household Finance and Consumption Survey collects household-level data on assets, liabilities, income and consumption. The survey is conducted by statisticians and economists from the European System of Central Banks and a number of national statistical institutes. The survey took place in 2010 and 2011 for the first wave and between 2013 and 2015 for the second wave (the third wave is currently under way).

- Arrondel,L et al, “How do households allocate their assets? Stylised facts from the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey”, ECB, 2016. Malmendier, U and Steiny, A., “Rent or buy? The role of lifetime experiences of macroeconomic shocks within and across countries”, Working Paper Series, UC Berkeley, January 2017.

- In Germany 43% of the stock of apartments is held by professional commercial landlords (including institutional investors) and another 42% by small private landlords; only around 15% is owner-occupied (European Public Real Estate Association). Anecdotal evidence suggests an increasing role of institutional investors, which are also absorbing the supply of new flats coming onto the market.

- For a discussion, see Box 3 entitled “Residential real estate prices in capital cities: a review of trends”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2017, which shows that in the second quarter of 2016 the growth in house prices in selected euro area cities outpaced the aggregate of the respective national averages by 3.7 percentage points.

- Besides land regulation and a number of other factors like construction costs, credit availability, the weather, etc., different spatial factors and historical patterns are also found to affect housing supply elasticities. For instance, the distribution of pre-existing land uses matters for local and aggregate supply elasticities, as shown by Ball, M., Meen, G. and Nygaard, C., “Housing supply price elasticities revisited: Evidence from international, national, local and company data”, Journal of Housing Economics, Vol. 19(4), 2010, pp. 255‑268.

- The European Commission’s Construction Survey sample also includes firms that operate in commercial real estate and civil engineering. However, as the factors affecting output in the residential construction sector are similar to those affecting the construction sector as a whole, the survey is informative of factors affecting production in the residential real estate sector.

- Restrictions are imposed for four periods (one year).

- For example, the broad category of demand shocks in the context of this simple model would also include monetary policy shocks and government spending shocks, e.g. incentives to families to buy a house. Supply shocks, on the other hand, would encompass, inter alia, oil-price shocks, which would contribute to higher production costs, as well as labour-supply shocks, e.g. changes in collective agreements between employers and trade unions active in the sector. A more elaborate model would be needed to further disentangle these broadly defined categories.