- THE ECB BLOG

How high corporate debt stifles investment

18 January 2023

Hit by multiple shocks, the corporate sector has increased its debt over recent years. The ECB Blog shows that strained balance sheets could significantly depress firms’ investment in the coming years with negative implications for innovation and growth.

A strong corporate sector is crucial for investment, innovation and eventually economic growth. Currently, the lingering COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and elevated energy prices stress the financial resilience of companies. Firms also remain challenged by the need to finance large-scale green investments. By comparison to larger firms, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have been particularly affected as they have lower equity. All of this drives corporate indebtedness. Against this backdrop we discuss the implications for corporate investment and answer the following questions in this post: Does high corporate debt act as a drag on investment following economic crises? Is investment by smaller firms more affected than that by larger firms? And when comparing euro area regions, are there differences in the impact on investment of a change in debt?

Negative impact of high corporate debt on investment

A negative link between high debt and investment is well established with several channels at work.[1] High corporate indebtedness implies higher interest expenses and thus less money available for investment. Firms with high debt also find it harder to obtain new funds from external sources due to their higher default risk. Moreover, the desire to repair weak balance sheets leads firms to reduce their debt burden, and thereby forgo investment opportunities.

In our recent study we shed light on the effects of firms’ debt-to-asset ratio on investment (defined as the change in total fixed assets) in the aftermath of crises. We use firm-level data for 14 euro area countries from 2005 to 2018.[2] We define a crisis period as a significant deviation from the historical value-added growth at the country-sector level.[3] Our exercise identifies 195 crises episodes corresponding to 7 percent of the firm-year observations, with the bulk of these episodes occurring during the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis.

Failing to address high leverage of SMEs affects large-scale investments.

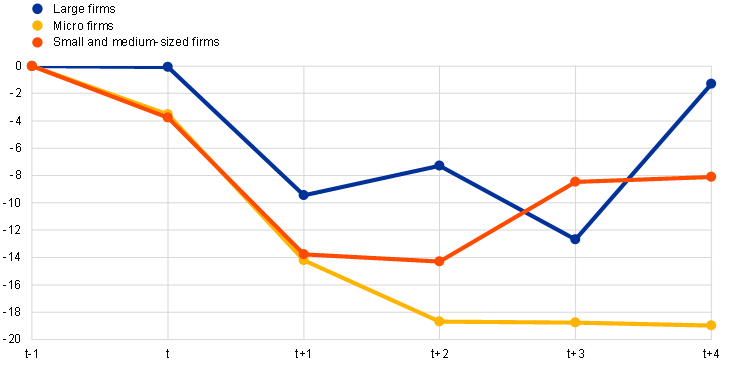

We find that investment by high-debt firms is significantly depressed for a long period following a crisis period (Chart). Over the four years after a large economic contraction, investment growth of high-debt firms is some 15 percentage points below that of their counterparts with lower debt burdens. Highly indebted micro, small and medium-sized firms experience a protracted fall in investment post-crisis. By contrast, higher leverage does not seem to influence the investment of larger firms, which typically have easier access to credit due to alternative sources of financing beyond bank financing and higher cash buffers compared to small firms.[4]

Chart

Investment response to a contraction in economic activity.

Investment by firm leverage

(Cumulative growth of tangible fixed capital, percentages)

Investment of high-debt firms by firm size

(Cumulative growth of tangible fixed capital, percentages)

Source: Barrela, R., Lopez Garcia, P. and Setzer, R., (2022).

Notes: A contraction in economic activity is defined as a large drop in sector value added growth (1.5 standard deviations below the sectoral historical average). The chart shows the cumulative impact (in percent) on tangible fixed capital at time t+h vis-à-vis t-1 of such an activity shock at time t. The impulse response functions are estimated using the local projection approach in Jordà, O (2005), Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review, Vol. 95(1). The sample comprises 14 euro area countries from 2005 to 2018. Low-debt firms are defined as firms in the bottom 20th percentile of the debt ratio distribution, medium-debt firms are firms between the 20th and the 80th percentile, and high-debt firms are firms standing above the 80th percentile of the distribution. Firm size is defined according to the number of employees. Micro firms have fewer than ten employees, small and medium-sized firms are those with fewer than 250 employees, and large firms have more than 250 employees.

Negative investment effects differ across European countries

Significant differences exist across countries in terms of the magnitude and persistence of the adverse investment effects. High-debt firms in Southern and Eastern European countries record a more pronounced and protracted fall in investment than their peers in Northern and Central Europe. This finding possibly relates to the absence of an efficient crisis management framework in the euro area, an adverse sovereign-bank-firm nexus or structural and institutional factors, such as the higher prevalence of small firms in Southern Europe or differences in the efficiency of national insolvency regimes. Our results are also consistent with the literature on zombie firms[5] which shows a) that the share of zombies is higher in Southern European countries than in other European regions and b) that zombie firms record lower investment than non-zombie firms. Additional analysis is however warranted to better understand differences in the sensitivity of investment to corporate debt across countries.

Taking a broader view on the whole euro area, we apply the above findings to tentatively assess the medium-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis on corporate investment. The COVID-19 shock led to a drop in euro area value added of 6.5% from 2019 to 2020, corresponding to about three standard deviations of the historical average. Using a simple accounting exercise, and abstracting from other determinants on investment, this implies a decrease in firm assets of around 5% by 2024 compared to 2019.

Changes to accounting rules could improve access to equity, benefiting SMEs

To sum up, we find strong evidence that high-debt firms invest less than their low-debt peers after crisis periods. In particular, a sizeable number of micro, small and medium-sized firms are located in “vulnerability regions” where debt, and hence reliance on external finance, negatively affects investment. Failing to address the high leverage of micro, small and medium sized firms could therefore negatively affect the capacity of the corporate sector to pursue large-scale investment needs over the coming years. What Europe needs is a well-capitalised corporate sector that broadens its funding sources beyond debt financing to promote the green and digital transitions, increase energy security, and support more diversified supply chains. This puts a premium on policies that promote greater equity as a buffer, thereby strengthening the prospect of sustainable investment growth. These include progressing towards a capital markets union, reducing the tax bias against equity financing, and ensuring access to timely and reliable information for equity investors. Changes to accounting rules could improve access to equity provided by private investors, with notable benefits for SMEs.[6]

Subscribe to the ECB blogThe views expressed in each article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

See Myers, S.C. (1977), “Determinants of corporate borrowing”, Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2), Gebauer, S., R. Setzer and A. Westphal (2018), “Corporate debt and investment: A firm-level analysis for stressed euro area countries”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 86(C), or Kalemli-Özcan, S., L. Laeven and D. Moreno (2022), “Debt Overhang, Rollover Risk, and Corporate Investment: Evidence from the European Crisis”, Journal of the European Economic Association, jvac018.

Barrela, R., Lopez-Garcia, P, and R. Setzer (2022), “Medium-term investment responses to activity shocks: the role of corporate debt”, ECB Working Paper No. 2751, European Central Bank.

Specifically, a crisis period is defined as a year in which the value-added growth at the country-sector level is at least 1.5 standard deviations below the average historical (2005-2018) value-added growth.

See Gopinath, G., S. Kalemli-Ozcan, L. Karabarbounis, and C. Villegas-Sanchez (2017), “Capital Allocation and Productivity in South Europe”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (4): 1915-1967, and Nicoletti, G., R. Setzer, M. Tujula, P. Welz (2022), “Assessing corporate vulnerabilities in the euro area”, ECB Economic Bulletin No. 2/2022.

Zombie firms are generally defined as high-debt firms that have persistent problems to cover their interest payments but keep operating for example due to bank forbearance or government support. See Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews, and V. Millot (2017), “The walking dead?: Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1372, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and Banerjee, R. and Hofmann, B. (2022), “Corporate zombies: Anatomy and life cycle”, BIS Working Papers No. 882, Bank for International Settlement.

See Group of Thirty (2020), “Reviving and Restructuring the Corporate Sector Post-Covid: Designing Public Policy Interventions, Report by the Group of Thirty’s Steering Committee and Working Group on Corporate Sector Revitalization” for policy measures that strengthen incentives for private investors to provide equity to viable firms in distress.