Inflation expectations and the conduct of monetary policy

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at an event organised by the SAFE Policy Center, Frankfurt am Main, 11 July 2019

Stable inflation expectations at levels consistent with price stability provide an important nominal anchor for the economy. They reduce inflation persistence and curb harmful macroeconomic volatility.

There is compelling empirical evidence suggesting that increased clarity about central banks’ mandates, their reaction functions and inflation aims has helped anchor inflation expectations and reduce their variability around the communicated inflation aim despite significant shocks to inflation in both directions.[1]

However, persistently low inflation since the great financial crisis has led some central bank observers, and financial market participants in particular, to question the ability of central banks to deliver on their mandate. In the euro area, where the coordinating role of a nominal anchor is particularly important in view of cross-country differences in wage and price-setting, market-based long-term inflation expectations have fallen since the crisis, and this fall has accelerated since the start of the year.

These developments have sparked a discussion on two related questions.

The first question, which I have discussed on previous occasions, is whether the fall in market-based inflation expectations reflects a growing belief that the ECB’s policy space is significantly reduced at the zero lower bound.[2]

The second question is whether similar shifts in the expected inflation outlook can be observed in the wider economy – that is, whether, and to what extent, market-based inflation expectations affect actual inflation outcomes and can become self-fulfilling by unleashing perilous second-round effects.

The decline in market-based inflation expectations

The first question is, in short, a discussion about the ECB’s credibility. While there is no room for complacency, I would argue that there are three arguments that provide some ground for comfort.

The first is that the drop in long-term market-based inflation expectations has been a global phenomenon, including jurisdictions where policy rates are currently well above the zero lower bound. This suggests that concerns by market participants likely extend well beyond the realm of monetary policy.

The second argument is that survey-based inflation expectations, such as the ones collected by the ECB in its Survey of Professional Forecasters, have stayed consistently above market-based measures, and closer to the ECB’s definition of price stability.

The third argument relates to the precise anatomy of the decline in market-based inflation expectations. ECB staff analysis suggests that market-based expectations are much more in line with survey-based inflation expectations once one corrects for the inflation risk premium – that is, the compensation investors demand for bearing risks related to the uncertainty around the future inflation path.

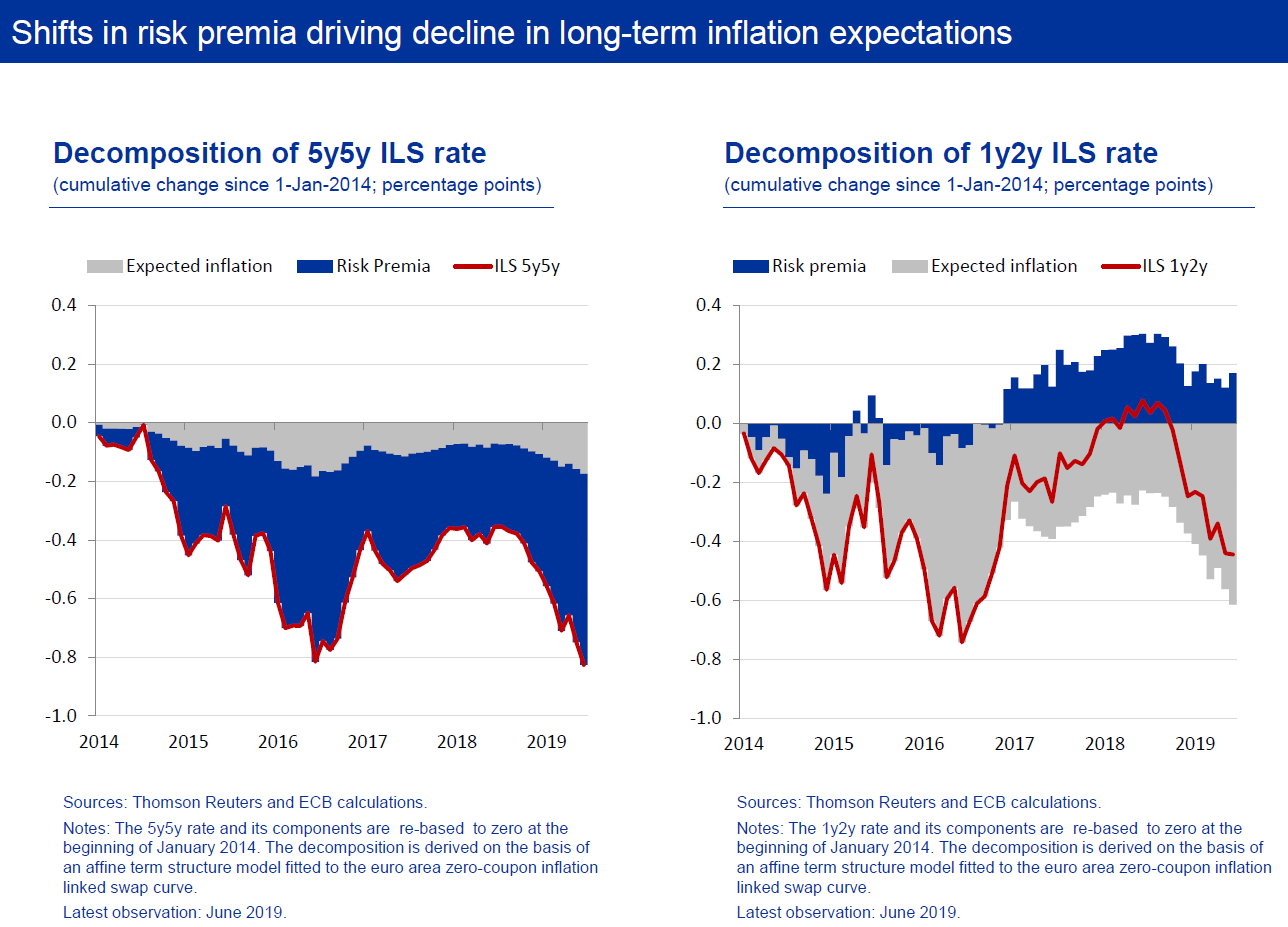

You can see this on the left-hand side of my first slide, which shows a breakdown of inflation-linked swap rates into expected inflation and an inflation risk premium. It suggests that about 80% of the drop in the five-year forward inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead, both since the start of 2014 and in 2019, is due to a drop in the risk premium.

Actual expectations have fallen to a much smaller extent. In other words, while expectations of a surge in euro area demand and inflation, as typically captured by a rising inflation risk premium, have been significantly cut, expectations about the baseline have remained more stable.

Yet, while shifts in risk premia can explain the bulk of recent developments in long-term inflation expectations, they can explain much less of the recent fall in short and medium-term expectations, which you can see on the right-hand side of this slide. Three-quarters or more of the decline in short and medium-term maturity inflation swap rates since the autumn of last year reflect a genuine fall in inflation expectations.

Such a drop in short and medium-term inflation expectations is particularly remarkable in an environment where highly volatile inflation components, such as energy prices, have remained relatively stable, and have even been rising since the start of the year. Recent market developments therefore suggest expectations that the current weakness in euro area and global demand will persist.

Households are not professional forecasters

This brings me to the second question as to whether similar shifts in the expected inflation outlook can be observed outside financial markets.[3]

One drawback of much of the empirical work on the role of inflation expectations is that it has largely assumed that all measures of expectations are interchangeable – that households and firms can be assumed to have expectations akin to those of professional forecasters or financial market participants.[4]

In reality, reliable data on inflation expectations of consumers or firms are scarce. I will return to firms in a minute but one reason for the lack of consumer expectations data is that several field studies have found that many people’s inflation perceptions are substantially different from actual inflation outcomes.[5]

For example, based on an experimental dataset maintained by the European Commission, households believed that annual euro area inflation between 2004 and 2018 was close to 9%, when in fact it was 1.6%.[6] Similar gaps have been found in the United States and elsewhere.[7]

Moreover, many households are not aware of central banks’ inflation aims. In the United States, for example, a recent survey showed that only a quarter of surveyed households knew of the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation aim.[8] This clearly suggests that central banks need to do much more to bring the monetary policy discussion to the broader public, and thereby improve their accountability.[9]

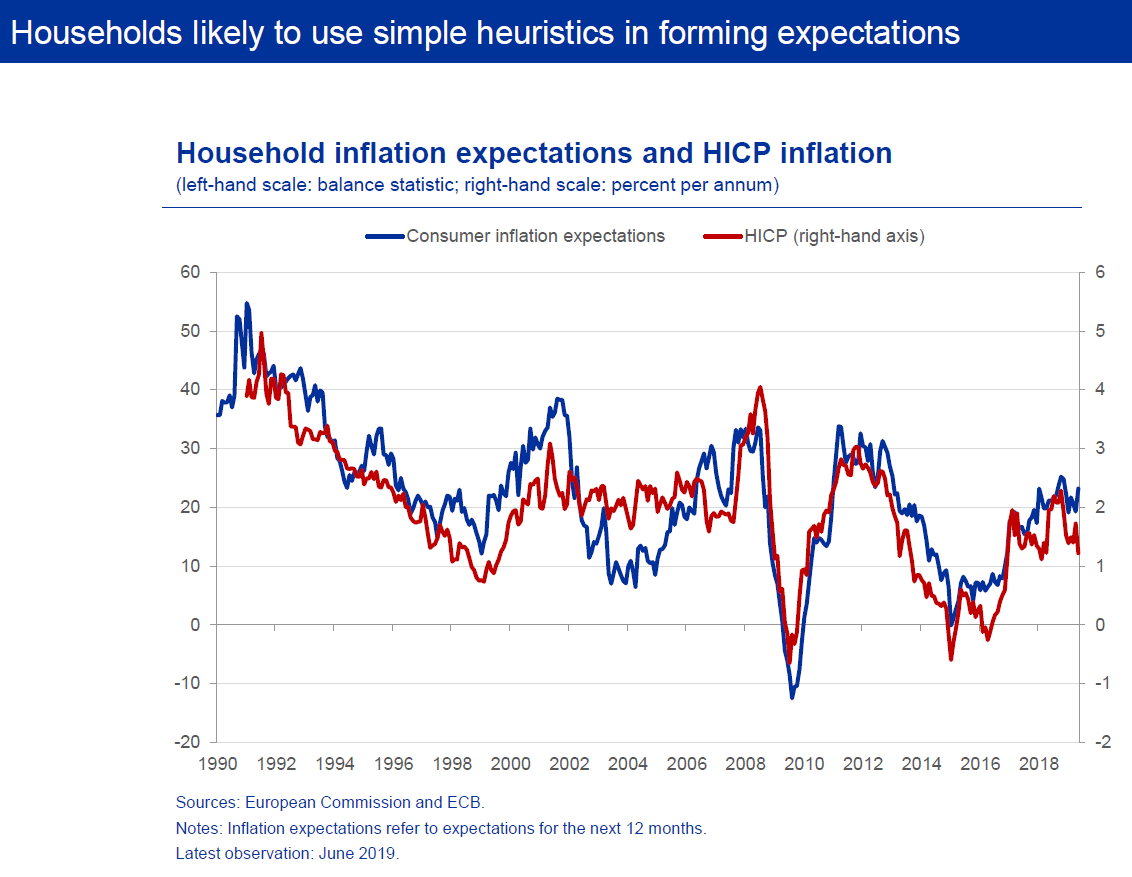

Yet, there is convincing evidence that, although households may not be able to correctly identify the current level of inflation, they have a fairly good understanding of changes in the trend of current inflation, and that these changes are likely to inform their expectations about future inflation.[10] You can see this on my next slide.

What you can see here is actual HICP inflation together with qualitative consumer inflation expectations for the following year, computed as a balance statistic which is the difference between the share of respondents who expect prices to rise and the share of those who expect prices to fall, or to stay about the same.[11] The correlation with actual inflation is remarkable.

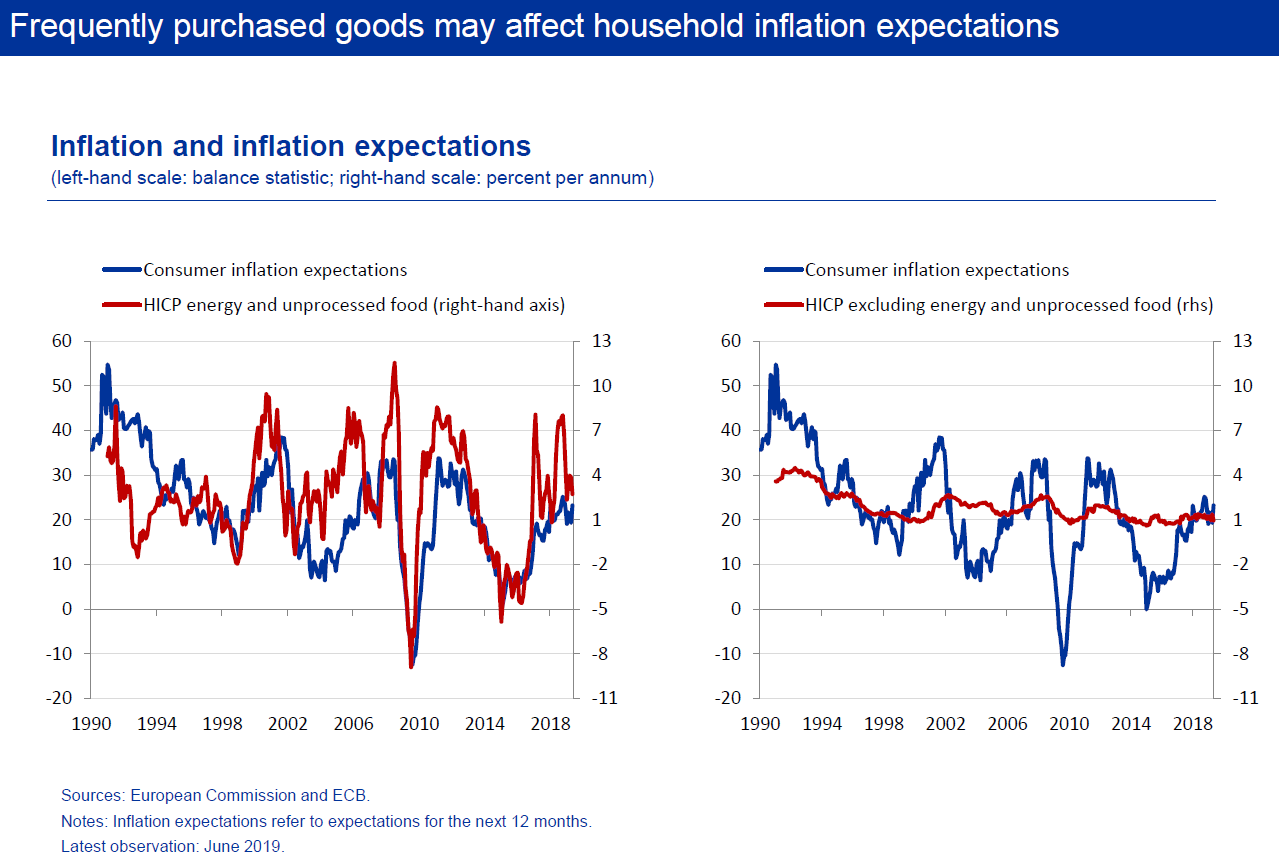

Much of this correlation is typically driven by price developments in some of the goods and services that consumers purchase more frequently. To put it simply, if goods are purchased more regularly, price changes are more likely to be noticed.[12]

You can see this on the left-hand side of my next slide, which relates household inflation expectations to annual inflation in energy and unprocessed food – products for which most consumers typically have a good understanding of price developments. Clearly, the correlation is much closer than when these two product categories are excluded, as you can see on the right-hand side.

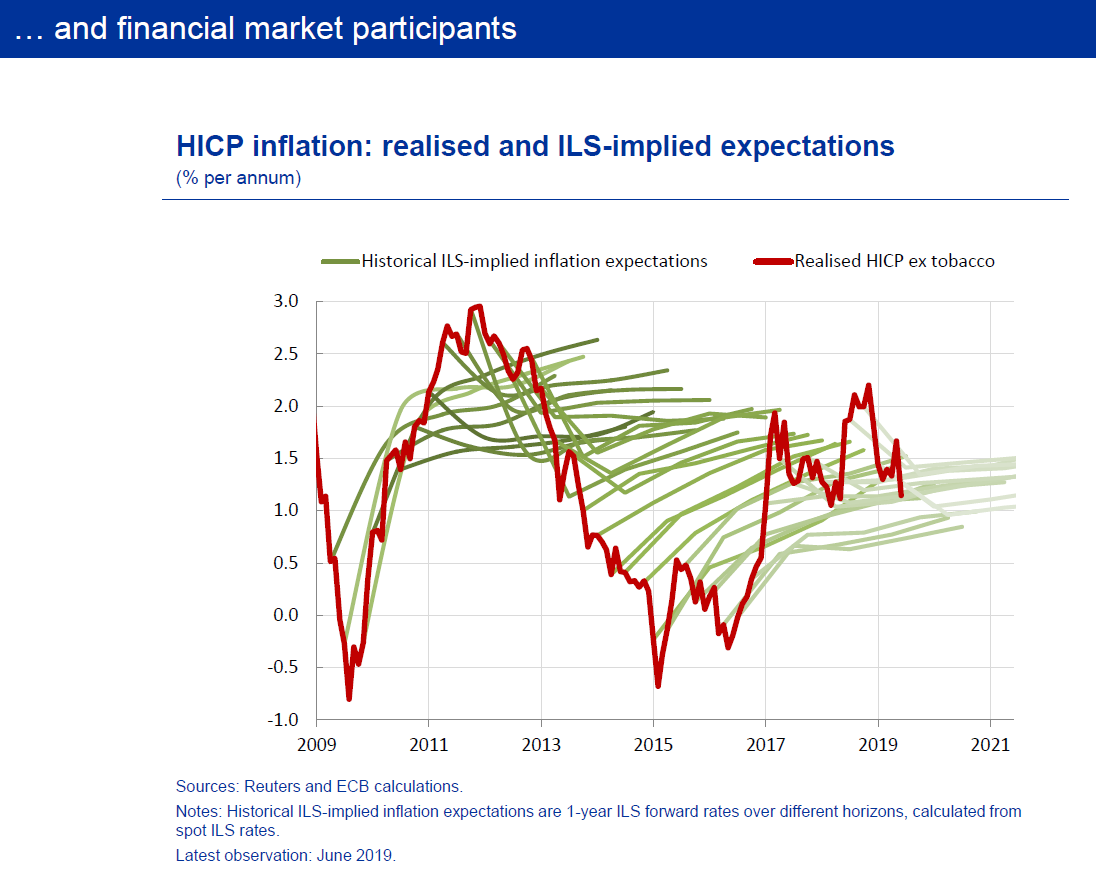

What is more, data on consumers’ inflation expectations indeed suggest that developments in market-based inflation expectations are often representative of trends in the wider economy. You can see this on my next slide.

Changes in the direction of household inflation expectations are typically very similar to those of professional forecasters, which are shown on the left-hand side, and financial market participants, which are shown on the right-hand side, at least for horizons of up to one or two years.

In other words, most individuals – whether financial investors, teachers or nurses – use simple rules of thumb to form their short-term inflation expectations. And current inflation seems to be the most widely used heuristic in this respect, making some degree of inflation persistence a natural and inevitable phenomenon.

Developments over the past year, however, mark a clear and visible departure from past regularities. As you can see on the right-hand chart, a growing gap has emerged between the inflation expectations of market participants on the one side, and households and professional forecasters on the other.

This is not about differences in the level, which – as I have argued before – may not mean much. This is about different dynamics, with the two-year moving correlation between market-based and household expectations dropping from 0.8 in the summer of last year to below 0.3 in June, the lowest level in nearly nine years.

So, unlike the situation in late 2014 and early 2015, when inflation expectations fell sharply across the population, and when we launched the asset purchase programme, today households are much less sceptical about the future.

This raises two important questions.

The first is what happens to inflation if financial market participants and households hold diverging views on the future direction of inflation.

The second question is why we are seeing this divergence in views, and whether it is temporary or likely to persist.

Let me try to answer each of these two questions in turn.

Which expectations matter most?

Existing research casts some doubt on the macroeconomic relevance of professional inflation forecasts, including those of financial markets. There are three related strands in the literature that suggest that household inflation expectations are often better predictors of future inflation outcomes.[13]

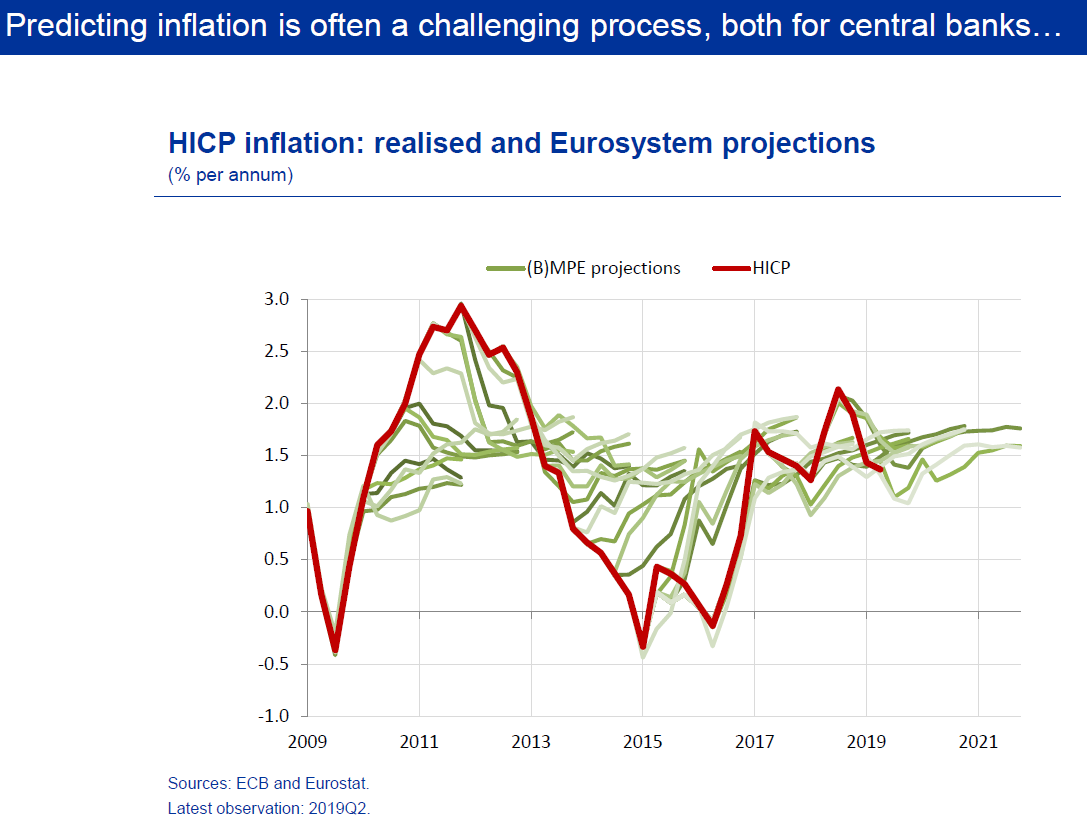

The first is that financial market participants are not particularly good at predicting future inflation. I’m not claiming that central banks are particularly better. You can see this on my next slide. But as you can see on the following one, financial market participants repeatedly failed to correctly project even the very near-term outlook for inflation in the euro area.

There are two sides to this finding.

One is the automatic stabilising role that market-based inflation expectations play despite, or precisely because of, their poor track-record in projecting inflation. As market participants react in real time to any news potentially relevant for the medium-term inflation outlook, they support the monetary policy transmission process: they tend to frontload accommodation when inflation risks are skewed to the downside, and they tend to remove accommodation when risks are tilted to the upside.

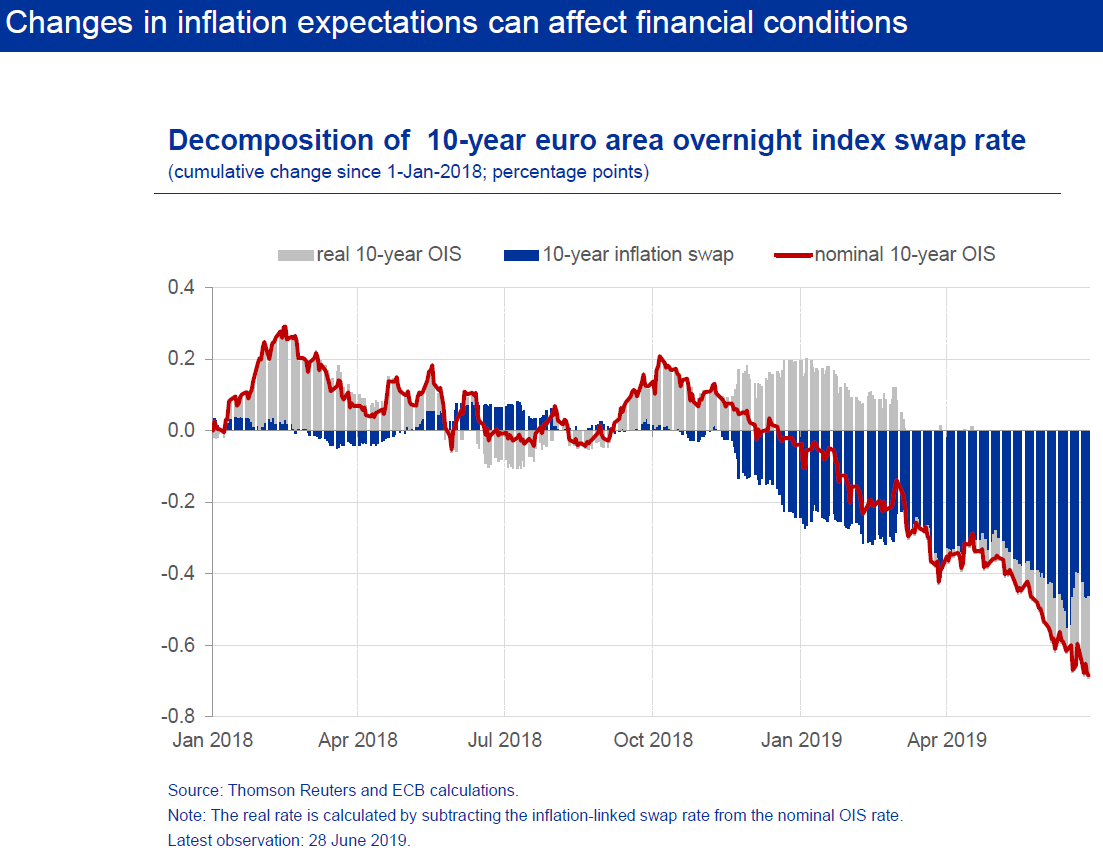

You can see this on my next slide, which shows the breakdown of the ten-year overnight index swap (OIS) rate into its real and nominal components. Clearly, shifts in inflation expectations can, at times, have a significant impact on financial conditions and hence on economic developments.

The other side of the coin is that, while a poor track-record in projecting inflation may not necessarily discourage their broader use in the economy, it is the high frequency of their revisions that probably makes market-based inflation expectations a less reliable and useful yardstick for social partners, firms and households in wage and price-setting, and hence a less reliable predictor of future inflation.

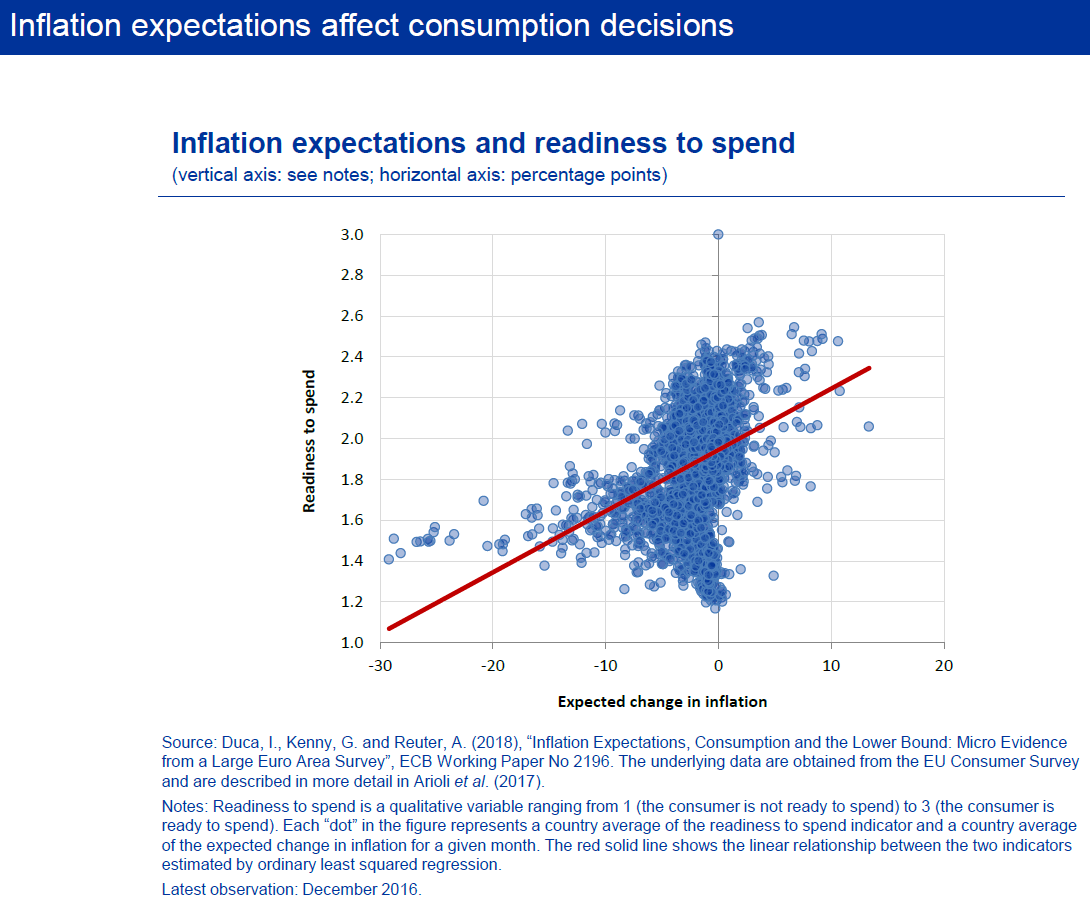

The second reason is that households’ inflation expectations affect their consumption decisions, and hence growth and aggregate price developments.[14] That is, when consumers expect inflation to rise, they tend to spend more today, much in line with the classical (real) interest rate transmission channel of monetary policy.

You can see ECB research on this on my next slide. There is a discernible positive relationship between households’ reported willingness to spend and the change they expect in inflation.[15]

The third, and possibly most important, reason is that household inflation expectations have been found to be a better proxy of firms’ pricing decisions than those of professional forecasters or financial market participants.

For example, research found that using household inflation expectations in an otherwise standard Phillips curve framework fits US inflation data better over a large sample. This includes the aftermath of the great financial crisis and was put forward as one factor explaining the “missing” disinflation puzzle in the United States.[16]

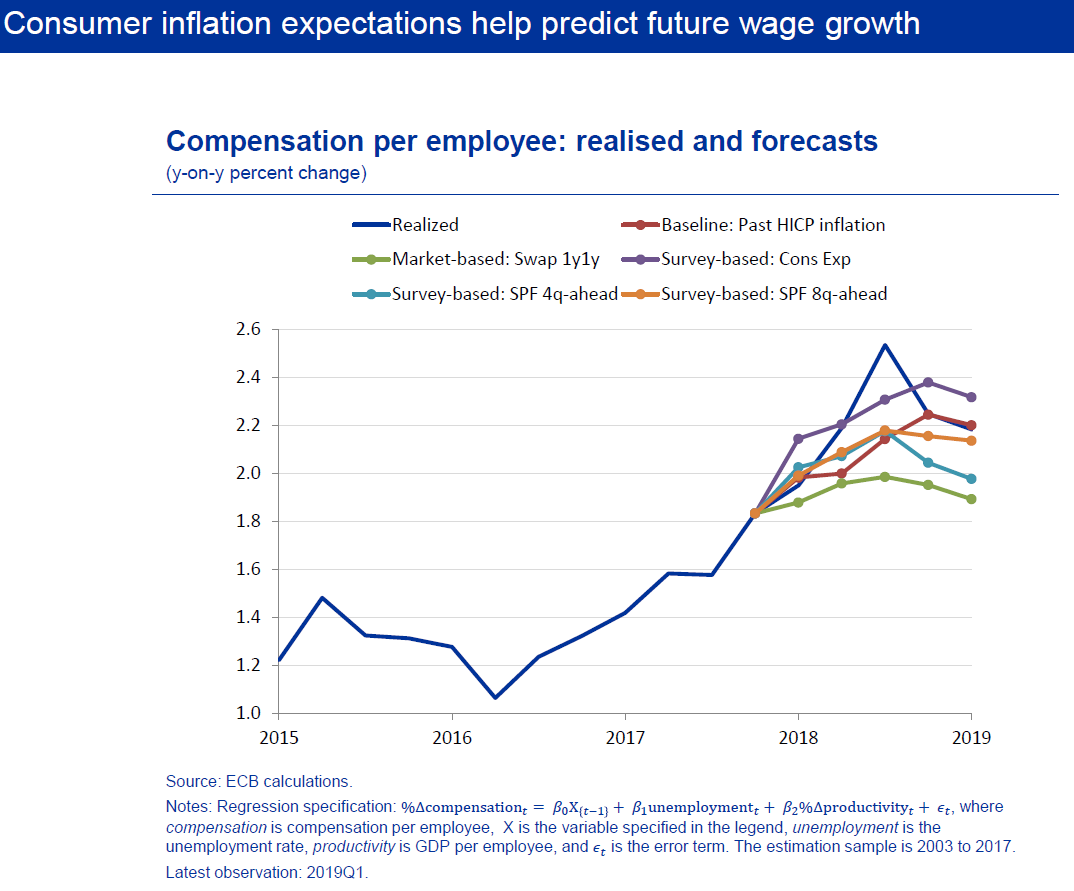

ECB staff find similar evidence for predicting wage growth in the euro area. You can see this on my next slide. Although the results need to be treated with caution given the short sample, a wage Phillips curve regression using household inflation expectations would have provided the best out-of-sample fit for euro area wage growth over the course of last year. For financial market-based inflation expectations, the prediction error would have been more than twice as large.

The few surveys that exist for firms’ inflation expectations corroborate these findings. The most comprehensive evidence exists for New Zealand, where firms’ expectations were found to be much closer to those of households.[17] In the United States, more than half of the survey respondents on a panel of firms in manufacturing and services said they were simply not able to report their point forecasts for inflation over the next 12 months, consistent with the evidence found for households.[18]

The implication is that, even though financing conditions largely depend on the expectations of financial markets, what ultimately matters for growth and inflation outcomes is how firms and households expect prices and wages to evolve in the future.

And so, while policymakers should never ignore signals coming from financial markets, they should not focus on them too narrowly either. The pessimism priced into bond markets today may not necessarily presage downward pressure on inflation tomorrow – at least not to the same extent.

How stable are household inflation expectations?

The second question relates to why inflation expectations between households and financial market participants are diverging at the current juncture. There is no easy answer.

One reason for the recent resilience in household inflation expectations may simply relate to the relative stability of the prices for some of the goods and services that consumers purchase more frequently. Looking through the ups and downs, inflation in energy and unprocessed food has been, on average, 4.5% between January 2018 and today, and it has never fallen below 2% during the course of 2019.

A second, and more benign, reason could relate to a change in how consumers extrapolate and generalise price changes in frequently purchased products.

Although the available data do not allow drawing definitive conclusions as to whether medium-term household inflation expectations have remained stable, my last slide suggests that they have.

It shows a very crude “deanchoring” measure, which combines, at each point in time, those euro area households that expect inflation to either “increase more rapidly” or “to fall” over the coming year – that is, expectations that are potentially not consistent with the ECB’s definition of price stability, depending on the state of the economy.

On the left-hand side, I show this measure together with an index of current inflation perceptions that weighs those households that perceive prices to have “risen a lot” with those who perceive them to have “fallen” over the past 12 months.

Clearly, while there was a correlation between these two indices in the 1980s and 1990s, this relationship weakened, and practically vanished, after the introduction of the euro. That is, euro area households, as a whole, do not expect prices to rise more rapidly in the future even in periods in which they perceive prices to have increased a lot over the previous 12 months.

On the right-hand side, you can see the same measure together with the HICP for energy and unprocessed food. From this chart it is clear that stability works in both directions. For example, the index barely moved when energy and food prices dropped sharply in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and it hardly moved when they rose markedly towards the end of 2016.

Such broad signs of anchoring – going beyond professional forecasters and financial markets – would also be consistent with empirical evidence that confirms that announcing an official inflation aim has contributed to reducing costly inflation persistence in a large group of developed and emerging economies, including the euro area.[19]

In other words, even though households continue to take current inflation into account when forming their expectations, the success of central banks in bringing inflation down to low and stable levels might have contributed to cutting the tails in the distribution of future expected inflation.[20] Such effects may have thereby helped to offset, at least partially, the consequences of other secular forces that have tended to make inflation more persistent.[21]

Conclusion

Stable inflation expectations play a crucial role for the effectiveness of monetary policy. For this and other reasons, central banks have over time radically changed the way they communicate with the public.

While increased central bank transparency has undoubtedly been successful in anchoring inflation expectations, the protracted period of low inflation has caused concerns among financial market participants that current subdued underlying price pressures will persist in the medium term. The Governing Council is taking these concerns seriously.

At the same time, euro area households seem to look with much less scepticism into the future. Their inflation expectations have remained more stable since the start of the year, and today remain close to a six-year high.

There is also tentative evidence suggesting that household inflation expectations are better predictors of future inflation outcomes and that euro area consumers have become less likely to expect inflation outcomes that would be inconsistent with the ECB’s definition of price stability.

All this confirms the need for central banks to consider and analyse developments in a broad set of inflation expectations indicators with a view to gauging risks to future price developments.

Thank you.

- [1]For an overview, see Blinder et al. (2008), “Central Bank Communication and Monetary Policy: A Survey of Theory and Evidence”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(4), pp. 910–945.

- [2]See Cœuré, B. (2018), “What yield curves are telling us”, speech at the Financial Times European Financial Forum, “Building a New Future for International Financial Services”, Dublin, 31 January; and Cœuré, B. (2019), “Heterogeneity and the ECB’s monetary policy”, speech at the Banque de France Symposium & 34th SUERF Colloquium on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the euro on “The Euro Area: Staying the Course through Uncertainties”, Paris, 29 March.

- [3]For a discussion of inflation expectations in the United Kingdom, see Tenreyo, S. (2019), “Understanding inflation: expectations and reality”, Ronald Tress memorial lecture, Birkbeck University of London, 10 July.

- [4]An exception is the recent contribution by Bernanke and co-authors. See Bernanke, B.S., Kiley, M.T. and Roberts, J.M. (2019), "Monetary Policy Strategies for a Low-Rate Environment," AEA Papers and Proceedings, American Economic Association, Vol. 109, pp. 421-426.

- [5]See Jonung, L. (1986), “Uncertainty about inflationary perceptions and expectations”, Journal of Economic Psychology 7, pp. 315-325; and Jonung, L. and Laidler, D. (1988), “Are perceptions of inflation rational? Some evidence for Sweden”, American Economic Review, Vol. 78, No. 5, pp. 1080-1087.

- [6]See Arioli et al. (2017), “EU consumers’ quantitative inflation perceptions and expectations: an evaluation”, ECB Occasional Paper No 186.

- [7]See, for example, Binder, C. (2017), “Fed Speak on Main Street: Central Bank Communication and Household Expectations”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 52, pp. 238–251; and Binder, C. and Rodrigue, A. (2018), “Household Informedness and Long‐Run Inflation Expectations: Experimental Evidence”, Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 85(2), pp.580-98.

- [8]See Coibion et al. (2018), “Inflation Expectations as a Policy Tool?”, NBER Working Paper No 24788.

- [9]See Cœuré, B. (2018), “Central banking in times of complexity”, panel remarks at a conference on the occasion of Sveriges Riksbank’s 350th anniversary, Stockholm, 25 May.

- [10]See Forsells, M. and Kenny, G. (2004), “Survey expectations, rationality and the dynamics of euro area inflation”, Journal of Business Cycle Measurement and Analysis, Vol 1(1), pp 13–42.

- [11]More precisely, the balance statistic is calculated as a weighted average of the percentage of those replying that consumer prices will “increase more rapidly” or “increase at the same rate” minus a weighted average of the percentage of those replying that they “stay about the same” or will “fall”, with the more extreme answers (i.e. “increase more rapidly” and “fall”) being assigned double weighting relative to the intermediate answers.

- [12]See also Coibion, O. and Gorodnichenko, Y. (2015), “Is the Phillips curve alive and well after all? Inflation expectations and the missing disinflation”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 7(1), pp. 197-232. The basic idea goes back to the Prospect-Theory developed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), which stated that the perception of economic situations depends on their framing. In other words, price changes are perceived during the act of purchase and the price change of a good is perceived more strongly the more often a good is bought. See Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979), “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk”, Econometrica, Vol. 47(2), pp. 263-91

- [13]See also Forsells and Kenny (2004, op.cit.).

- [14]See Duca, I., Kenny, G. and Reuter, A. (2017), “Inflation Expectation, Consumption and the Lower Bound: micro evidence from a large euro area survey”, ECB Working Paper No 2196; D’Acunto, F., Hoang, D. and Weber, M. (2016), “The effect of unconventional fiscal policy on consumption expenditure, NBER Working Paper No 22563; and Ichiue, H. and Nishiguchi, S. (2015). Inflation expectations and consumer spending at the zero bound: Micro evidence, Economic Inquiry 53(2), pp. 1086–1107.

- [15]This analysis uses quantitative estimates of household inflation expectations.

- [16]See Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2015, op.cit.).

- [17]See Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y. and Kumar, S. (2018), "How Do Firms Form Their Expectations? New Survey Evidence", American Economic Review, 108 (9), pp. 2671-2713.

- [18]See Coibion et al. (2018, op.cit.). Of the remaining respondents, the average forecast was 3.7%, well above what professional forecasters and financial market participants were expecting but close to the forecasts of households.

- [19]See Kocenda, E. and Varga, B. (2018), “The Impact of Monetary Strategies on Inflation Persistence”, International Journal of Central Banking, September; Benati, L. (2008), “Investigating inflation persistence across monetary regimes”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 123(3), pp. 1005–1060; Bratsiotis, G.J., Madsen, J. and Martin, C. (2015), “Inflation targeting and inflation persistence”, Economic and Political Studies, 3 (2015), pp. 3-17; and Levin, A. T., Natalucci, F. M. and Piger, J. M. (2004), “Explicit inflation objectives and macroeconomic outcomes”, ECB Working Paper No 383.

- [20]This is also consistent with evidence that households have a much better understanding of actual inflation outcomes in high-inflation economies. By contrast, most households and firms in low inflation countries do not view inflation as being a major consideration in their consumption and investment decisions. See, for example, Frache, S. and Lluberas, R. (2019), “New Information and Inflation Expectations among Firms”, BIS Working Paper No 781.

- [21]These forces include the rise of services in our economies. See Cœuré, B. (2019), “The rise of services and the transmission of monetary policy”, speech at the 21st Geneva Conference on the World Economy, 16 May.

Eiropas Centrālā banka

Komunikācijas ģenerāldirektorāts

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Pārpublicējot obligāta avota norāde.

Kontaktinformācija plašsaziņas līdzekļu pārstāvjiem