The role of the European Union in fostering convergence

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Conference on European Economic Integration (CEEI), Vienna, 26 November 2018

This[1] conference was renamed 14 years ago to reflect the “growing together of Europe”.[2] In my remarks today I would like to focus precisely on these three topics: growth, Europe and togetherness. I will argue that these three elements are needed to accomplish what the Treaty on European Union promises: economic and social cohesion.[3]

I will focus my remarks today on the economies of central, eastern and south-eastern Europe (CESEE), covering both those that are already part of the European Union (EU) and those that are EU candidate countries or potential candidates.[4]

I will start with a brief review of the current state of convergence of CESEE economies, and then explain how three key European policy areas – the completion of the Single Market, the launch of a true capital markets union and the targeted use of EU funds – can help accelerate convergence and thereby also foster cohesion in Europe.

The current state of convergence

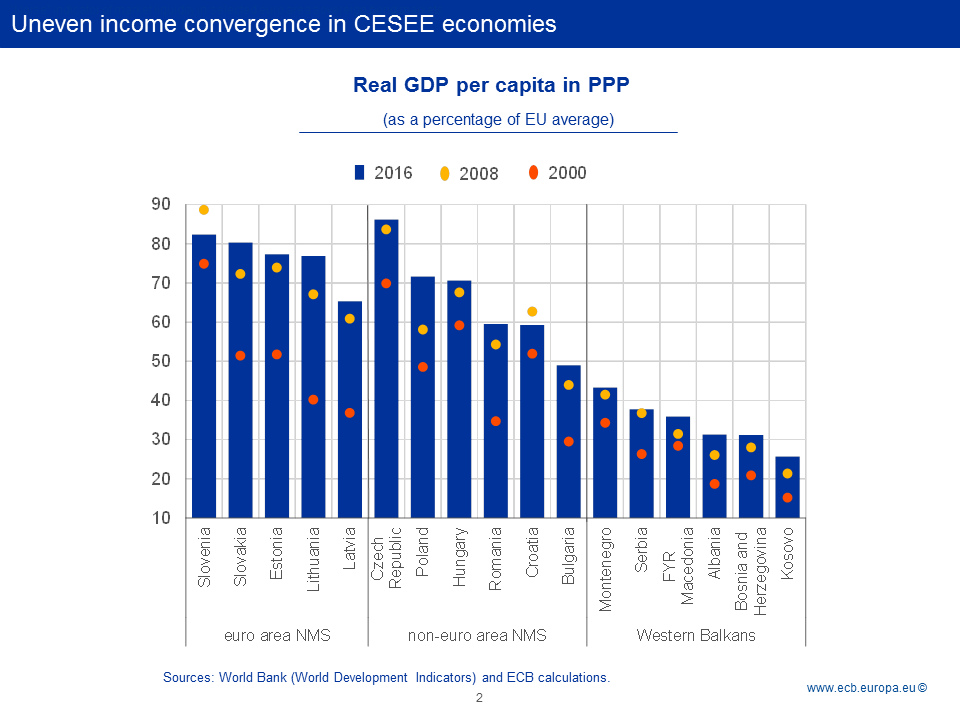

CESEE economies have seen significant improvements in living standards over the past two decades, in both absolute and relative terms.[5] Since 2000, growth in real GDP per capita has averaged 3.8% in the region as a whole, compared with 1.4% for the EU-28. As a result, we have seen these economies make measurable and welcome progress in catching up to the EU average.[6]

But this catching-up process has been neither linear over time nor homogeneous across countries. You can see this on my first slide.

Clearly, for most countries, convergence towards the EU-28 average has practically stalled since the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008 – this is the difference between the yellow dot and the upper end of the blue bar.

And before the crisis, convergence was noticeably faster in economies that were already part of the euro area. In many of these economies, relative living standards increased by half, from 40 to 50% of the EU average in 2000, to around 70% in 2016. But the further one moves to the right on this slide, and contrary to what neoclassical growth theory would suggest, the less compelling strong convergence becomes.

In the Western Balkans, for example, while relative income levels have increased, they have done so at a much slower pace. At current growth rates, fast convergence towards the EU-28 average will remain illusory for many EU candidate countries or potential candidates.

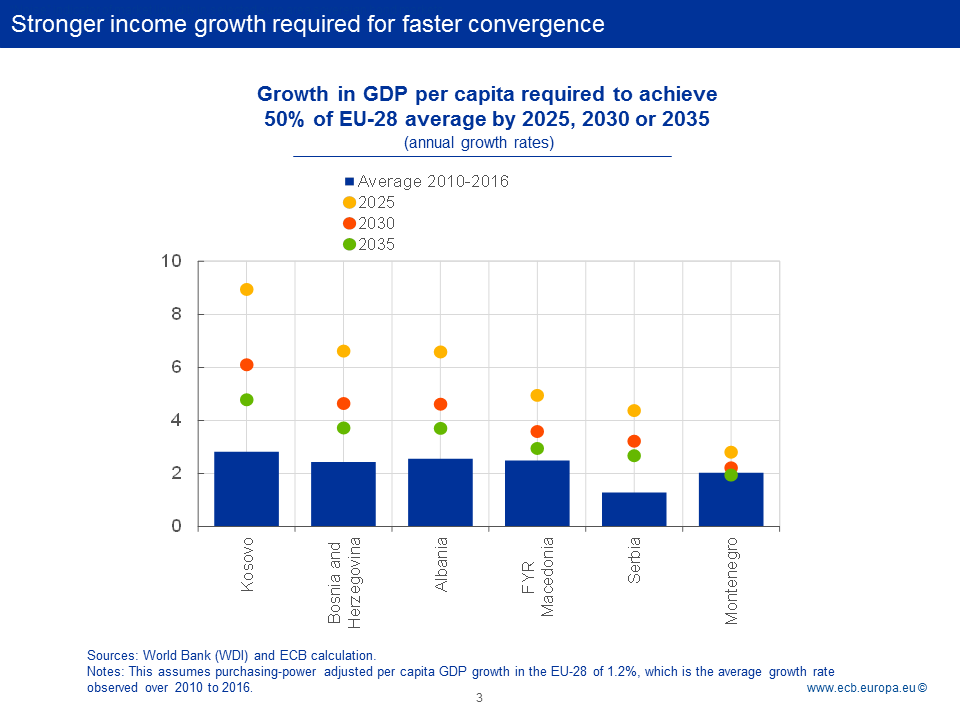

These economies, and this you can see on my next slide, would need much higher GDP growth rates than in previous years to even reach half of the EU-28 average within the next 20 years or so, with the possible exception of Montenegro.

Clearly, this pace of convergence is disappointing. It implies that living standards in Europe will remain highly varied and uneven for a considerable period of time, even within the EU. And if there is no credible prospect of lower-income countries catching up soon, there is a risk that people living in those countries begin questioning the very benefits of membership of the EU or the currency union. Such doubts would be particularly worrisome in the unstable world we are currently living in.

We need the EU to remain a force for change, a source of growth and development and an anchor of stability. Action is therefore needed on two main fronts: first, to bring convergence in EU Member States back onto its pre-crisis path and, second, to jump-start convergence in EU candidate countries and potential candidates.

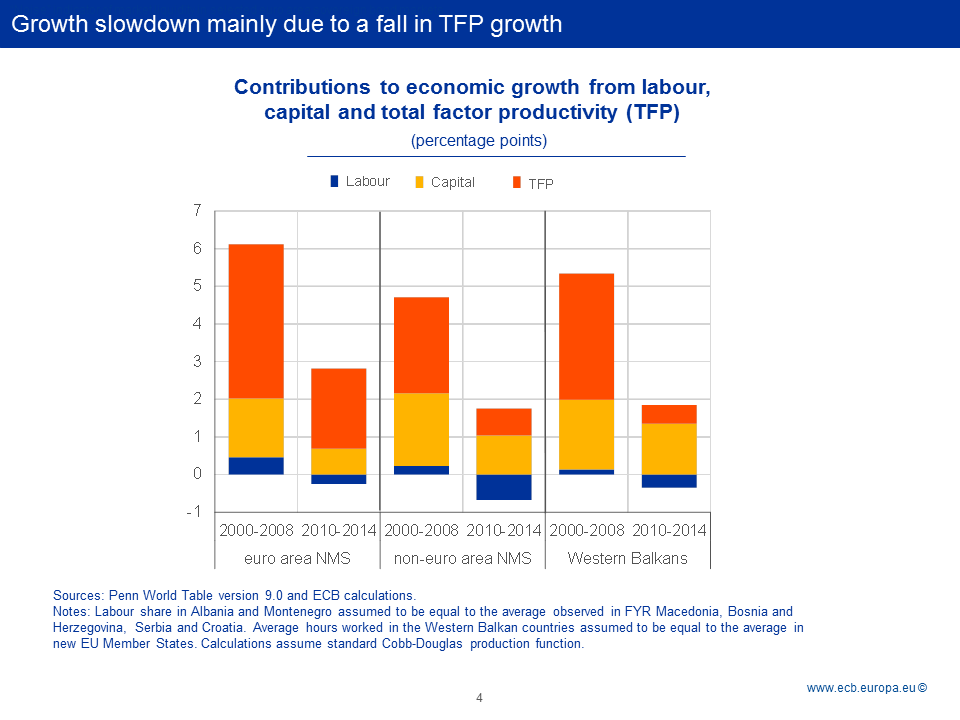

To understand what needs to be done to tackle both challenges, it is useful to look at the drivers of growth and the factors that have recently been holding them back. You can see this on my next slide.

What you can see here is that, since the crisis, growth in all CESEE economies has essentially slowed because of two main factors: a sharp drop in total factor productivity (TFP) growth and, to a lesser extent, in the contribution of capital to growth.

There are two things worth highlighting here.

The first is that it is highly unusual that pre-crisis convergence largely reflected technological progress and innovation. During the transition phase, growth is typically based on capital and labour accumulation, and only later on TFP growth.[7] Or, to borrow the words of Paul Krugman, it is based first on perspiration and only later on inspiration.[8]

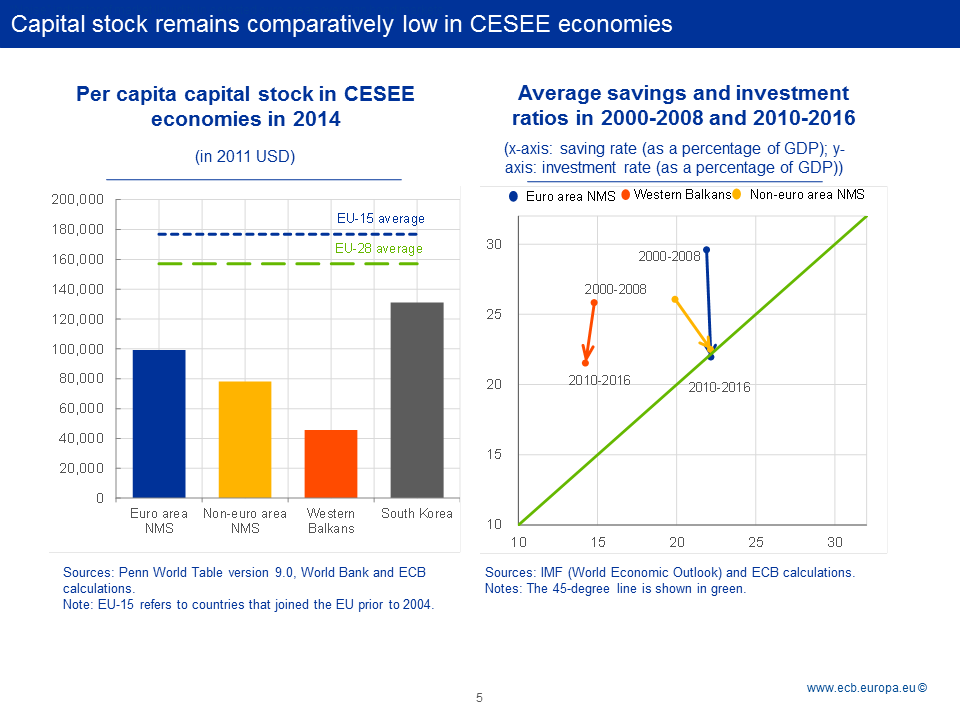

The flipside is that these economies are now faced with a notable capital shortfall. The capital stock per person employed remains substantially below the EU-28 average in almost all CESEE economies. You can see this on my next slide on the left-hand side.

In CESEE euro area Member States, it also remains well below other emerging economies, such as South Korea, with similar per capita income levels. And, worse, investment rates have fallen further since the crisis in all CESEE economies. You can see this on the right-hand side.

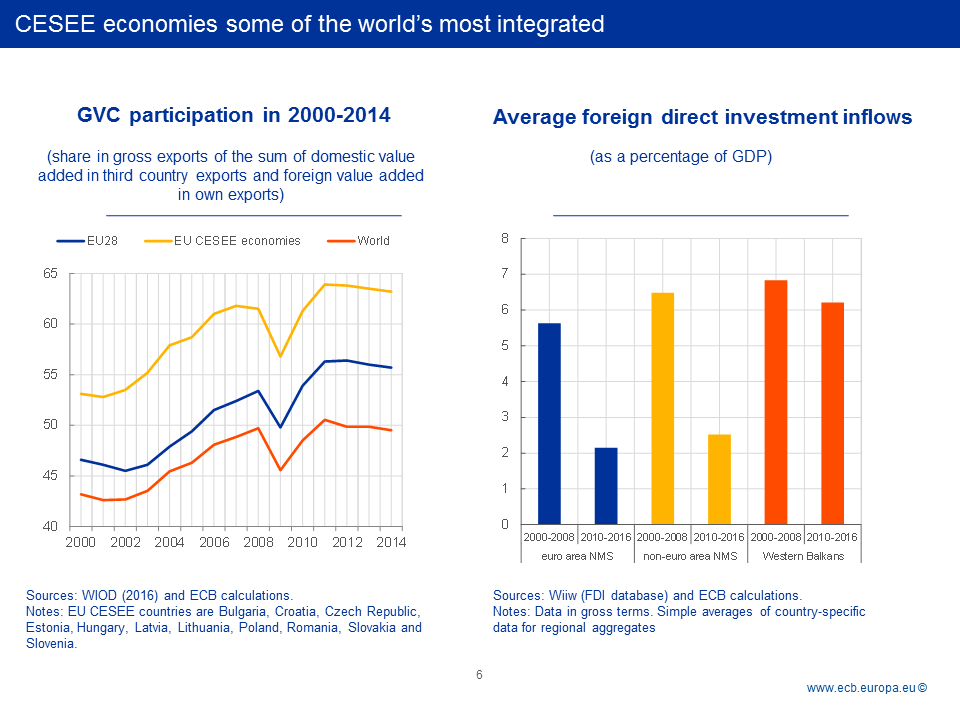

The second fact worth highlighting is that the remarkable contribution of productivity to growth, both in the upswing and in the downturn, is likely to be an artefact of the growth model adopted by most CESEE economies. This growth model relies, by and large, on deep integration in global production chains.

You can see this clearly on my next slide. CESEE economies are some of the world’s most integrated. They are far more integrated in global value chains than their EU peers, for example. Sizeable foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in the pre-crisis period – which you can see on the right-hand side – have promoted the role of CESEE economies in global production processes. These inflows accounted for around 6% of GDP in the run-up to the crisis. In the EU-28 as a whole, FDI inflows accounted for just 3.4% of GDP over this period.

The role of FDI in supporting TFP growth is well known.[9] By integrating local firms into global value chains, it facilitates the transfer of technology and expertise. The transfer of technology, moreover, does not stop at firms directly integrated into global value chains, but also extends to their domestic suppliers via local production networks.[10]

Empirical evidence shows that, in the case of central and eastern European (CEE) economies, this transfer of technology has contributed to both strong TFP growth in the run-up to the crisis and to its more recent slowdown.[11]

You can see this more clearly on my next slide. There is a very close link between TFP growth in CEE economies and TFP growth in non-CEE EU countries. This link likely reflects the scale and scope of technology spillovers.[12] So, as FDI inflows decelerated and participation rates in global value chains levelled off, TFP growth in CESEE economies abated too.

Global value chains as a source of TFP growth in the future

In sum, therefore, this diagnosis highlights two key facts: CESEE economies have a lack of capital, and a strong reliance on global production processes.

The easy answer, of course, is to brush away weakness in FDI inflows as a temporary phenomenon. After all, if the law of declining marginal returns on capital continues to hold, we should still expect capital to flow into catching-up economies, rebooting TFP growth.

I would be somewhat more cautious, however. It is true that weakness in trade and investment, worldwide, has been part of the collateral damage from the crisis. As we leave this legacy behind, headwinds should fade too.

But the recent shift is also likely to reflect developments of a more structural nature – that is, the slowdown in global value chain formation may well persist.[13]

There are three main reasons for this. First, natural disasters and increasing climate-related disruptions have led firms to rethink the length and design of their value chains to mitigate the risks of costly supply disruptions.[14] This is becoming increasingly visible and may still amplify as climate change takes its toll on our economies.

Second, in the past sizeable wage differentials for unskilled labour made the international fragmentation of production processes worthwhile. Some of these wage differentials have narrowed considerably as emerging economies have grown richer. In the EU CESEE economies, for example, real wages have increased by slightly more than 50% since 2000. In the EU-28, real wages grew by 18% over the same period.

And, third, the increased use of robots and artificial intelligence has the potential to turn global value chains on their head and cause firms to reconsider offshoring practices.[15]

The second and third factors may be the most pressing ones.

Put simply, if robots can deliver the same output more cheaply, more efficiently and closer to the consumer, then firms may have fewer reasons to spread production across countries. By some estimates, the average price of industrial robots has declined by about 40% over the past ten years and is projected to fall considerably further.[16] A survey by the Boston Consulting Group revealed that more than 70% of senior manufacturing executives in the United States think that robotics improve the economics of local production.[17]

The implication is that, to the extent that growing automation and narrowing wage differentials make the outsourcing of production processes less profitable, policymakers in CESEE economies, and in emerging market economies more generally, will need to think about developing other growth models.

To reboot TFP growth and deepen capital accumulation they will need to stimulate domestic investment spending and help new, innovative industries to grow and develop. Only in this way will convergence towards the EU-28 average accelerate.

These should be joint efforts, however, which brings me to the second part of my remarks. Europe can and should help, in three main ways. First, by providing the market that makes the development of new industries profitable. Second, by channelling funds to sectors and countries where capital can be used most productively. And, third, by providing direct financial assistance to foster convergence and support national reform efforts.

Reaping the benefits of the Single Market

Let me take each of these points in turn, starting with the market dimension.

The EU’s Single Market can be a valuable source of competitive advantage for firms located in CESEE economies, in particular when competing with other economies at similar stages of development.

It is the largest market in the world, offering the benefits of enormous economies of scale, and has helped establish product and safety standards that are used worldwide. There is compelling evidence that the Single Market has had a positive impact on exports, investment, innovation and productivity.[18]

To exploit its full potential, and to accelerate convergence, two things need to be done.

First, Member States need to strengthen its enforcement so that Single Market initiatives translate into concrete and positive effects on the ground.

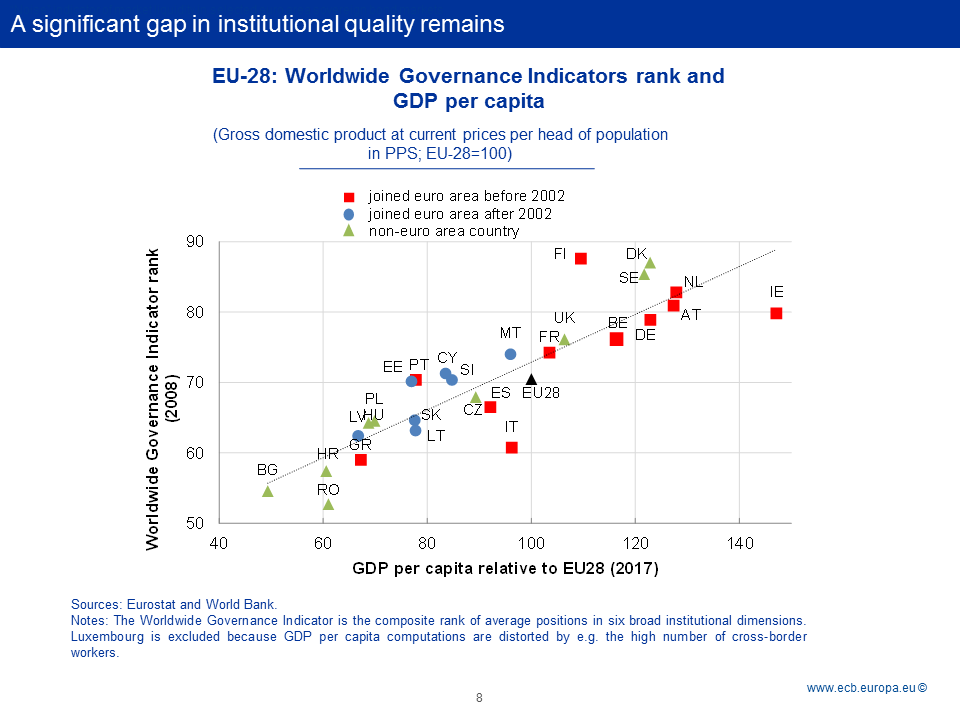

A key ingredient for this is efficient administration at all levels of government. Indeed, a lack of real convergence in income levels is, more often than not, the result of a lack of convergence in institutional quality.[19] You can see this on my next slide – a slide I like to show because I think it makes a compelling point, notwithstanding the usual caveat on the two-way causality between institutional quality and income levels.[20]

Most CESEE economies are still in the lower left-hand corner, meaning there remains a significant gap in overall institutional quality compared with the average level observed in the EU as a whole.

Some EU Member States have recently renewed their interest in the process leading to participation in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) and the adoption of the euro. This could become a fundamental catalyst for institutional reforms in the years to come.

Second, the scope of the Single Market must be broadened.

For the EU, this means expanding its reach into industries that are prime drivers of innovation and catalysts for future growth.

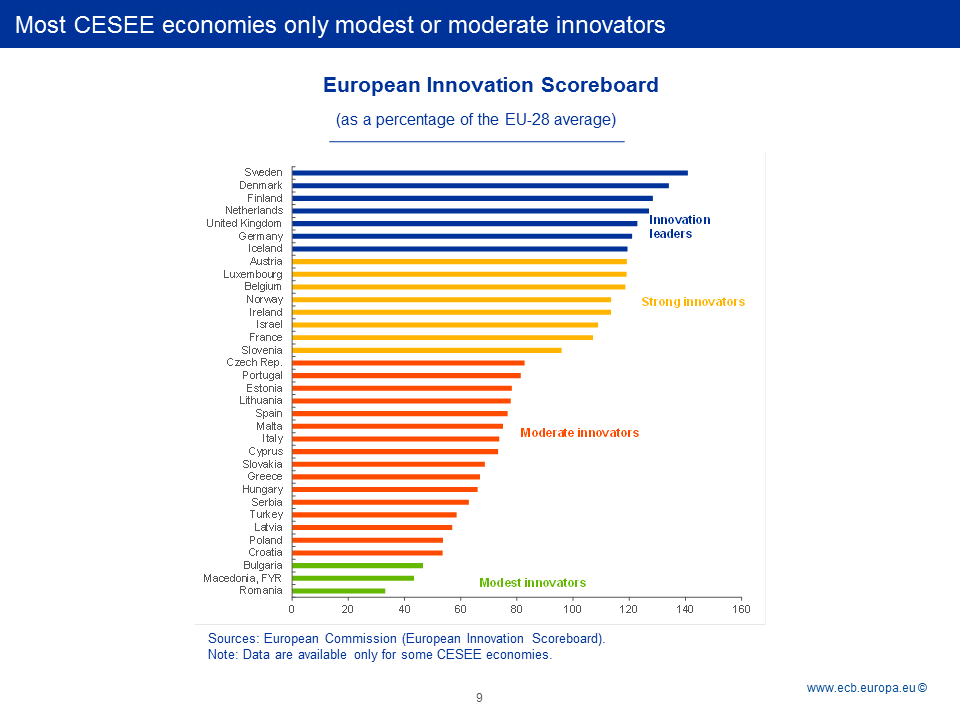

This is particularly relevant for CESEE economies. As you can see on my next slide, most of these countries are still classified as modest or moderate innovators. There have been some notable improvements in certain countries over time, but in others the process of gradually catching up with their EU peers appears to have stalled, or even to have backtracked, in recent years.

The first priority is therefore to complete the Single Market for services, which already account for two-thirds of global GDP and employment, and represent many of the potential growth sectors in the age of digitalisation and automation.

Research by the ESCB’s Competitive Research Network (CompNet) shows, for example, that many firms in the EU services sector are far behind the productivity frontier, particularly in CESEE economies.[21] Reallocating capital and labour to more productive firms would help boost overall competitiveness and support employment.

A second, and more direct, avenue is to increase efforts to build a “European data economy”, or a digital single market, as also advocated by the European Commission in its communication last week.[22] Digitalisation offers a particularly promising opportunity for catching-up economies to leapfrog more advanced economies and adopt new technologies faster than them, thereby mitigating the risk of being hurt by reshoring and premature deindustrialisation.

Convergence and the role of the capital markets union

The second key area where Europe can help – which is close to the heart of this conference – is by channelling funds to where they can be used most productively.

There is compelling evidence of the importance of finance for technological innovation and, ultimately, long-run growth rates.[23] Differences in the quality of financial intermediation across countries have been found to have significant implications for economic growth.[24]

In particular, research is increasingly challenging the view that bank and market-based finance tend to support economic development and living standards in similar ways.

Evidence is growing globally that large banking systems are associated with more systemic risk and lower economic growth, in particular as countries grow richer.[25] In addition, recent work by ECB staff highlights that, during the euro area sovereign debt crisis, capital misallocation increased substantially among firms that were more reliant on bank finance.[26]

Other research suggests that deeper equity markets are more effective in promoting innovation and productivity and, hence, in bringing economies closer to the technological frontier.[27] Recent ECB research, for example, suggests that if an EU Member State were to increase its ratio of stock market capitalisation to bank credit from the 25th to the 75th percentile, the average growth rate of its most high-tech industry could be expected to increase by 3.1 percentage points, everything else being equal.[28]

None of this is to say that banks will become redundant. They will continue to play their key social role of pooling savings and engaging in maturity and risk transformation.

But recent findings are increasingly reflected in the ongoing policy discussion. The European push towards a capital markets union, for example, reflects not only the need for increased cross-border risk-sharing in a currency union, but also the hope that deeper and better-integrated equity markets will support innovation and productivity growth in the European Union.[29]

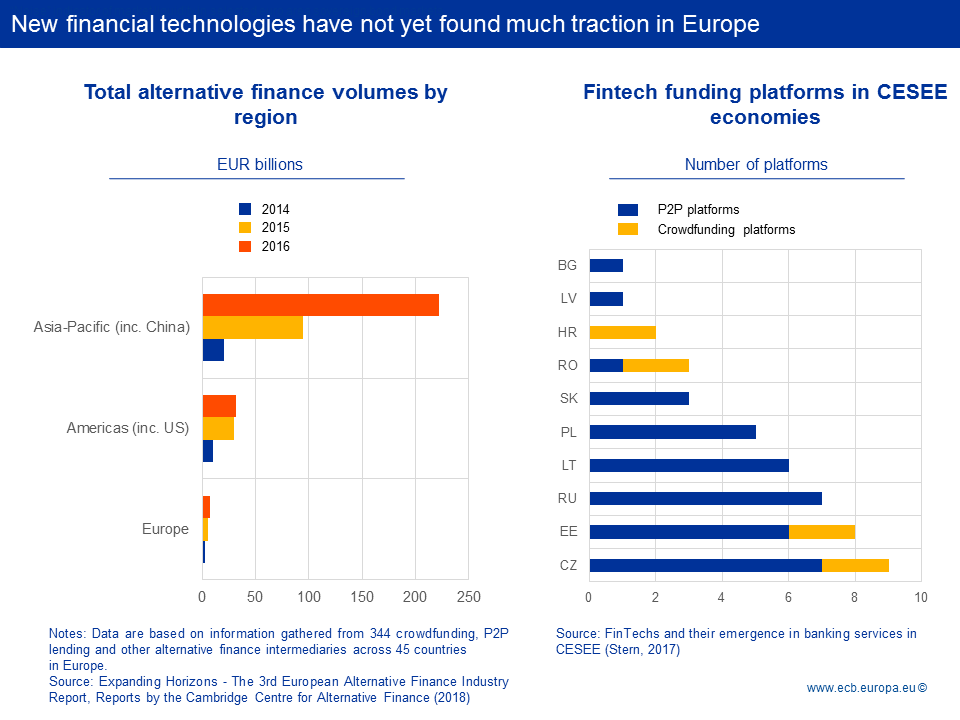

This also includes making new innovative financial technologies available to firms and ensuring they are as safe as conventional technologies. Europe is spearheading this process. Europe’s Payment Services Directive (PSD2), for example, has been revised to introduce more competition in financial intermediation by requiring banks to share account information with new contenders.

China, of course, is a prime example of new financial technologies supporting growth in the transition towards higher income levels. Although EU data requirements are more stringent – for good reason – there is considerable scope for such technologies, if used prudently, to also foster growth and convergence in the EU.

On my next slide you can see that in Europe more generally, and in most CESEE economies in particular, these technologies have not yet gained much traction. In other words, progress towards a true capital markets union can both support the funding of investments, thereby helping overcome the current lack of capital accumulation, and, at the same time, foster the use and distribution of new financial technologies that may themselves become a source of growth.[30]

Using EU funds to foster convergence

The third area where Europe can help is arguably the most contentious one. It relates to transfers between Member States to foster convergence in the EU.

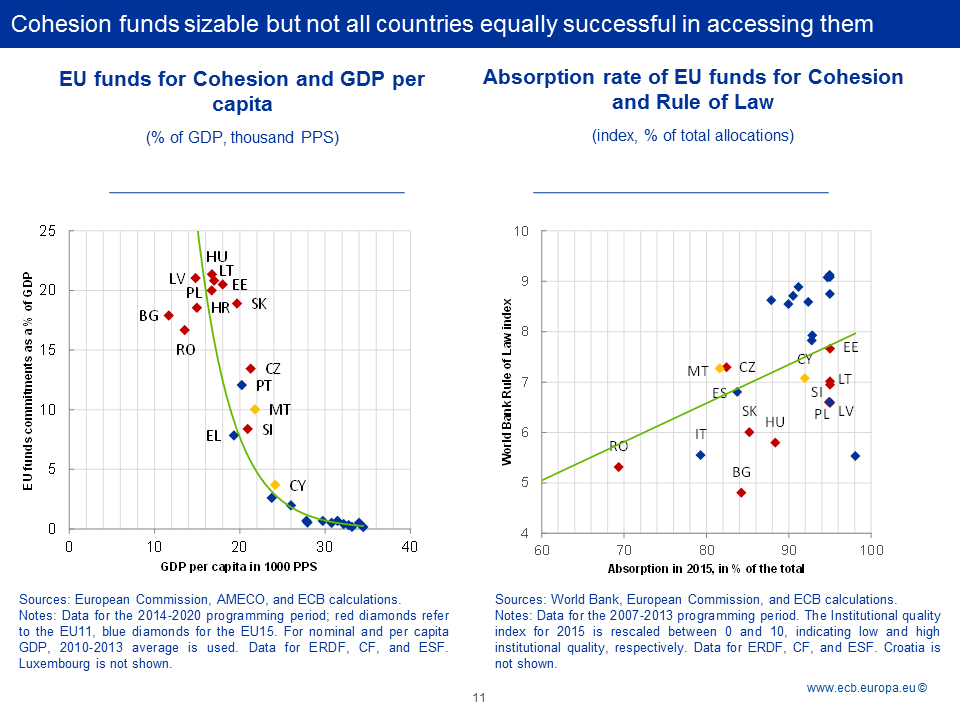

Such transfers are already happening, of course. Cohesion policy, designed to reduce structural disparities among regions and Member States, was the second largest item in the EU’s 2014-20 budget. Over this period, and this you can see on the left-hand side of my last slide, the cumulated available funds for CESEE countries range from 8 to 21% of average annual GDP, with the allocation of resources linked to prevailing income levels. In other words, these funds are not negligible.

One problem, however, is that not all countries are equally successful in accessing them. One reason for this is linked to the importance of institutional quality, which I mentioned earlier. You can see this on the chart on the right-hand side, which suggests there is a positive correlation between institutional quality and a country’s ability to effectively absorb available transfers and secure new funding opportunities.

Such patterns are even more visible when considering EU funding opportunities for social policies, education and training.[31] Under the European Fund for Strategic Investments plan, for example, CESEE economies have only been able to attract less than 5% of total funding allocated to social infrastructure projects.

This means two things.

First, we need to strengthen the ability of receiving economies to access and absorb funds. This should be part of the broader effort to improve institutional quality.

Second, EU allocation rules should be made as simple as possible. The European Commission has already made several important suggestions in this respect, with a single rulebook planned to cover several EU funds, less red tape and lighter control procedures for businesses and entrepreneurs benefiting from EU support.[32] Such initiatives are essential if we want people and companies to take full advantage of the opportunities that the EU provides.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Achieving similar standards of living across our continent should speak to our highest aspirations. It is a recognition of history that economic prosperity, opportunity and peaceful societies are closely linked and mutually reinforcing. The prospect that relative income levels in Europe, without further action, will remain unacceptably large for the foreseeable future is therefore a warning sign. It should urge policymakers to think in new ways about how convergence can be accelerated, and what role Europe itself should play in this process.

I have highlighted today that we must begin by acknowledging that convergence requires joint efforts and responsibility. It requires Member States to translate EU initiatives and recommendations into concrete and positive effects on the ground, and candidate countries and potential candidates to achieve institutional excellence as early as possible in the transition process. Convergence must be built on strong institutions. And adhering to standards, EU standards, is a powerful vehicle for growth.

Accelerating convergence also requires the EU, and the euro area in particular, to help underwrite this process. This includes completing the Single Market, building a new digital market and being serious about developing a true capital markets union. Transition economies need both the market and the capital to nurture and feed domestic growth initiatives.

Thank you.

- [1]I would like to thank Alessandro Giovannini for his contributions to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

- [2]See Liebscher, K. (2004), “Opening Remarks”, Conference on European Economic Integration, Vienna, 29 November.

- [3]Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union states that “[The Union] shall promote economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member States.”

- [4]EU members comprise Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia. EU candidate countries or potential candidates comprise Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia (also referred to here as the “Western Balkans”). Kosovo is also included subject to data availability (without prejudice to positions on status, in line with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 and the International Court of Justice’s opinion on Kosovo’s declaration of independence).

- [5]See also Nowotny, E., D. Ritzberger-Grünwald and H. Schuberth (2018), “Structural Reforms for Growth and Cohesion – Lessons and Challenges for CESEE Countries and a Modern Europe”, Edward Elgar Publishing.

- [6]See Zuk et al. (2018), “Real convergence in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe”, ECB Economic Bulletin Article, Issue 3.

- [7]See, for example, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2017), Transition Report 2017-18, November.

- [8]See Krugman, P. (1994), “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle”, Foreign Affairs, November/December.

- [9]See, for example, Girma, S. (2005), “Absorptive capacity and productivity spillovers from FDI: a threshold regression analysis”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 67(3), pp. 281-306; Amann, E. and S. Virmani (2014), "Foreign direct investment and reverse technology spillovers: The effect on total factor productivity", OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2014/1; Alfaro, L., S. Kalemli‐Ozcan and S. Sayek (2009), “FDI, productivity and financial development”, World Economy, 32(1), pp. 111-135; Kimura, F. and K. Kiyota (2006), “Exports, FDI, and productivity: Dynamic evidence from Japanese firms”, Review of World Economics, 142(4), pp. 695-719; and Arratibel, O., F. Heinz, R. Martin, M. Przybyla, L. Rawdanowicz, R. Serafini and T. Zumer (2007), “Determinants of growth in the central and eastern European EU Member States – a production function approach”, ECB Occasional Paper No 61.

- [10]See, for example, Kee, H. L. (2015), “Local intermediate inputs and the shared supplier spillovers of foreign direct investment”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 112, pp. 56-71.

- [11]See, for example, Bas, M. and V. Strauss-Kahn (2014), “Does importing more inputs raise exports? Firm-level evidence from France”, Review of World Economics, Vol. 150(2), pp. 241-275; and Bustos, P. (2011), “Trade Liberalization, Exports, and Technology Upgrading: Evidence on the Impact of MERCOSUR on Argentinian Firms”, American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No 1, pp. 304-340.

- [12]See Chiacchio, F., K. Gradeva and P. Lopez-Garcia (2018), “The post-crisis TFP growth slowdown in CEE countries: exploring the role of Global Value Chains”, ECB Working Paper No 2143. This research also suggests that sectoral TFP growth in CEE countries depends roughly equally on technology creation at the global value chain frontier and on the ability of national firms to absorb the new technology.

- [13]See Cœuré, B. (2018), “Trade as an engine of growth: Prospects and lessons for Europe”, speech at the NBRM High Level International Conference on Monetary Policy and Asset Management, Skopje, 16 February.

- [14]See also Cœuré, B. (2018), “Monetary policy and climate change”, speech at a conference on “Scaling up Green Finance: The Role of Central Banks”, organised by the Network for Greening the Financial System, the Deutsche Bundesbank and the Council on Economic Policies, Berlin, 8 November.

- [15]See also United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2016), “Robots and Industrialization in Developing Countries”, Policy Brief No 50.

- [16]See, for example, Sirkin, H., M. Zinser and J. Rose (2015), “How Robots Will Redefine Competitiveness”, Boston Consulting Group, September.

- [17]See Boston Consulting Group (2015), “Made in America, Again: Fourth Annual Survey of U.S.-Based Manufacturing Executives”, December.

- [18]See, for example, Monteagudo et al. (2012), “The economic impact of the Services Directive: A first assessment following implementation”, European Commission Economic Papers No 456; Blind, K., A. Mangelsdorf, C. Niebel and F. Ramel (2018), “Standards in the global value chains of the European Single Market”, Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 25(1), pp. 28-48; and Pelkmans, J. and A. Renda (2014), “Does EU regulation hinder or stimulate innovation?”, CEPS Special Report No 96.

- [19]See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Convergence matters for monetary policy”, speech at the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet) conference on “Innovation, firm size, productivity and imbalances in the age of de-globalization” in Brussels, 30 June.

- [20]See Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson and J. Robinson (2001), “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation”, American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 5, pp. 1369-1401.

- [21]See ECB (2017), “Firm heterogeneity and competitiveness in the European Union”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

- [22]See European Commission (2018), “The Single Market in a changing world – A unique asset in need of renewed political commitment”, Brussels, 22 November.

- [23]See Levine, R. (2005), “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence”, in Aghion, P. and S.N. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, pp. 865-934, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- [24]See Boyd, J.H. and B.D. Smith (1992), “Intermediation and the equilibrium allocation of investment capital: Implications for economic development”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 30(3), pp. 409-432.

- [25]See Langfield, S. and M. Pagano (2016), “Bank bias in Europe: effects on systemic risk and growth”, Economic Policy, Vol. 31(85), pp. 51-106; and Demirgüç-Kunt, A., E. Feyen and R. Levine (2013), “The evolving importance of banks and securities markets”, World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 27(3), pp. 476-490.

- [26]See Bartelsman, E., P. Lopez-Garcia and G. Presidente (2017), “Factor reallocation in Europe”, ECB, mimeo.

- [27]See Hsu, P., X. Tian and Y. Xu (2014), “Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 112(1), pp. 116-135.

- [28]See ECB (2018), “Financial development, financial structure and growth: evidence from Europe”, Financial integration in Europe, May. Moreover, higher growth in value added has been found to be driven by faster growth in labour productivity than in capital accumulation, supporting the idea that equity markets play an important role in the financing of innovation and TFP growth.

- [29]See ECB (2015), Building a Capital Markets Union – Eurosystem contribution to the European Commission’s Green Paper; and ECB (2017), ECB contribution to the European Commission’s consultation on Capital Markets Union mid-term review 2017.

- [30]See also Stern, C. (2017), “Fintechs and their emergence in banking services in CESEE”, Focus on European Economic Integration, Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Issue Q3/17, pp. 42-58.

- [31]Here most of the EU funds are allocated via tenders and competitive calls, not via pre-allocated grants on the basis of quotas at Member State level.

- [32]See European Commission (2018), “EU budget: Regional Development and Cohesion Policy beyond 2020”, press release, 29 May.

Eiropas Centrālā banka

Komunikācijas ģenerāldirektorāts

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Pārpublicējot obligāta avota norāde.

Kontaktinformācija plašsaziņas līdzekļu pārstāvjiem