Ladies and Gentlemen,

Seven years have passed since the financial market turmoil in the summer of 2007 marked the beginning of the financial crisis and the ensuing recession. These years have been challenging for all central banks. They have marked the end of a long period of remarkably stable, good macroeconomic performance. The widespread adoption of an explicit price stability objective had been conducive to low inflation outcome in an environment of prolonged economic growth. Existing monetary policy strategies—mostly variants of the inflation targeting model, though with notable exceptions at the ECB and at the Federal Reserve—appeared to be adequate and sufficient to attain this goal. Consistently with the Tinbergen principle, the primary objective of price stability was achieved everywhere through a single, conventional monetary policy instrument: a short-term interest rate.

The global financial crisis changed this situation abruptly. Since then, some central banks have been endowed with additional macro-prudential instruments and a more explicit mandate to preserve financial stability. While no explicit change in monetary policy strategies has taken place, it is fair to say that there has been a generalised increase in the attention paid to banks’ balance sheet conditions and to the evolution of credit. By far the most visible innovation since the beginning of the Great Recession however, has been the increase in the array of instruments used for monetary policy purposes, particularly forward guidance about interest rates and most notably the use of central banks’ balance sheets through Large Scale Assets Purchases (LSAP, i.e. Quantitative Easing or QE).

In theoretical debates, other proposals were made namely, to change the targets of monetary policy to price level targeting or to nominal GDP or simply, to increase the established objective of 2% in inflation targeting regimes to 3% or 4%. For practical reasons, these proposals were not retained and forward guidance and QE were the new instruments of choice for many central banks.

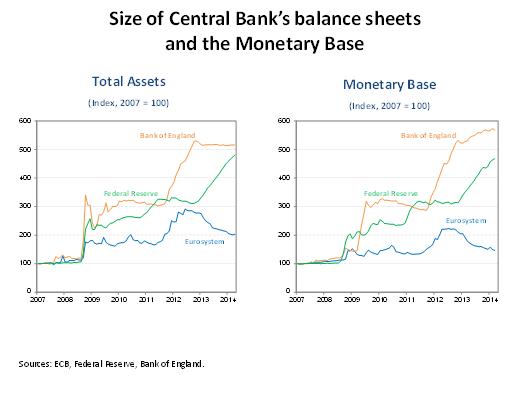

Before the crisis, the established instrument of monetary policy was a short-term interest rate steered either by traditional open-market operations of buying and selling securities or through temporary lending to banks via repos, like in the ECB’s case. After the crisis, all major central banks significantly increased their balance sheets and the respective monetary base.

Chart 1

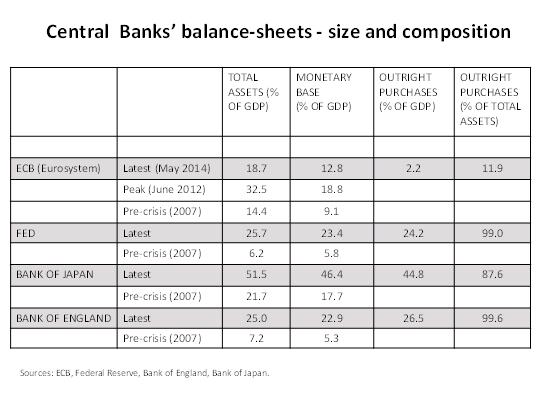

It would, nevertheless, be misleading to compare the changes in balance sheet size as if they were originated by the same policies and, consequently, had the same impact. The case of the ECB is different from the other central banks as the expansion of the balance sheet happened as the result of lending to the banks through repos of different maturity. The increase in the balance sheet was dependent on the demand of primary liquidity by the banks, facilitated however, by the provision of liquidity through a regime of fixed rate full allotment of banks’ demand, introduced in September 2008. The impact on overall monetary conditions was, as before the crisis, dependent on the behaviour of the banks to pass-through the higher monetary base into credit and broad money, which did not happen. What did happen was a justified fulfilment of the role of lender of last resort but not a new type of monetary policy instrument in the sense of aiming at a new transmission channel. The adoption of a fixed-rate full allotment regime of liquidity provision, which has been in place since and was recently extended until December 2016 (at the very least) was indeed an extraordinary unconventional measure. It supported the banking sector and avoided a more detrimental credit crunch. However, the size of our monetary base declined significantly during 2013 when banks decided to start the repayment of their previous high borrowings. On the other hand, as per the following table, total outright purchases of assets by the ECB under two different programmes was not behind the increase of the balance sheet as they represent a relatively small proportion of total assets compared with other central banks.

Table 1

Before the crisis, both methods of conducting liquidity management transactions (via outright purchases or lending to the banks) previously mentioned, had the objective of steering a short-term interest rate close to the policy rate decided by the central bank. It would therefore be misleading to interpret the increase of banks’ balance sheets through LSAP or QE as just an increase in scale of the traditional outright purchases. There is a different objective of intervening directly in different asset markets and in higher maturities in order to influence the respective prices or yields. The intention and the composition of the assets purchased are thus relevant and different from what was previously done to manage short-term rates. QE has several transmission channels: besides the direct impact on prices/yields of the purchased assets (Treasuries or ABSs), it triggers portfolio adjustments on other assets, like equities or exchange rates, and is accompanied by wealth effects. While the theoretical debate on the exact channels of transmission remains active, many event and time-series studies have tried to measure the QE effects. John Williams (2013) presents a survey of several studies and reports that USD 600 billion of FED asset purchases achieves a result equivalent to a cut in the federal funds rate of 0.75 to 1 percentage point. [1]

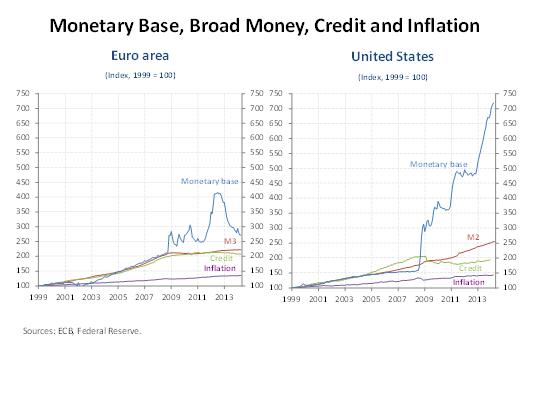

The concerns expressed by various economists and the media that the extraordinary increases in the monetary base in many countries would lead to significant inflation rates, never materialised. As the following slide illustrates, there was no transmission in the prevailing economic situation by the banks, to credit or broad money aggregates. Inflation did not respond, putting in doubt the quantitative vision about its origin. When asked about what Japan should do to overcome deflation, Milton Friedman answered in 2000: “It is very simple. They can buy long-term government securities and they can keep buying them and providing high-powered money until the high-powered money starts getting the economy into an expansion”. [2] The more recent Japanese experience is still open to analysis but the channels envisioned by Milton Friedman have seemingly not been operating in the other advanced economies. As mentioned, the transmission channels at play in the recent QE experiences are indeed different from the traditional quantitative view.

Chart 2

The ECB Monetary Policy in the European crisis.

As the financial crisis led to the Great Recession and then evolved into the European sovereign debt crisis, the ECB started providing liquidity in fixed-rate full allotment mode, progressively and considerably extended the maturity of its loans to commercial banks, widened the set of eligible collateral, made medium-scale purchases of financial assets and announced the Outright Monetary Transactions programme.

As a result of these extraordinary measures, at the end of 2012 calm started returning in financial markets, leading to lower financial spreads and a reduction in volatility. The initial signs of economic recovery started appearing. Preliminary formal analyses indicate that non-standard measures were instrumental in supporting financial intermediation and economic activity in the euro area. [3]

Despite these recent, encouraging developments on the financial side, real economy recovery has been weak and inflation outcomes have been surprisingly low. The new challenge we face in the euro area today is to avert the risk of a prolonged period of excessively low inflation. Euro area annual HICP inflation was 0.5% in May 2014, after averaging 0.7% in the first four months of the year. The June 2014 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections foresee a gradual increase in annual HICP inflation towards levels consistent with our definition of price stability. The pace of the increase is, however, slow. From 0.7% in 2014, inflation is expected to reach 1.1% in 2015 and, more uncertainly, 1.4% in 2016. All three figures have been revised downward in comparison with the March 2014 ECB staff macroeconomic projections and portray a situation distant from our objective of keeping inflation below but close to 2% in the medium-term.

Inflation developments alone go a long way in motivating the combination of the measures announced by the Governing Council of the ECB on 5 June, to provide additional monetary policy accommodation and to support lending to the real economy. This package included further reductions in the key ECB interest rates, new longer-term refinancing operations targeted to stimulate credit creation, and preparatory work related to outright purchases of asset-backed securities. In addition, the ECB committed to an extension of the fixed-rate full allotment regime in tender procedures and decided to suspend the weekly fine-tuning operation sterilising the liquidity injected under the Securities Markets Programme. Over time these measures will contribute to a return of inflation to levels closer to 2% and safeguard the anchoring of medium to long-term inflation expectations.

Nevertheless, with policy interest rates close to the effective lower bound and persistently timid growth prospects, there is a small, but non-insignificant risk that any additional adverse shock may open the door to a more protracted period of low inflation. Against this background, I would like to organise the rest of my remarks today around three issues.

First, why do we find ourselves in the current, low inflation predicament? I sustain that inflation fluctuations have been somewhat surprising ever since the beginning of the Great Recession. In part, they were the result of adverse exogenous shocks. To some extent however, they were also connected with unwarranted variations in markets’ expectations of the future stance of monetary policy.

Second, I will argue that the Governing Council meeting at the beginning of June is important not only for the decisions that were actually adopted. It is important also for the clear signal that we provided about the determination to do more in the future, in the event of additional downward pressures on inflation. I will develop these two points which deal with the way our recent policy decisions will produce effects.

The third question is: how would the ECB react, should the risks of a protracted period of low inflation materialise? At this point in time, this is essentially a scenario analysis—and specifically an analysis of a low probability scenario. Outright purchases of a range of financial assets would be effective in this situation, but structural reforms would also be essential to spur economic growth.

Inflation developments since the Great Recession

Euro area inflation developments over the past six years have been remarkably volatile.

From the 4.1% peak of July 2008, HICP inflation fell markedly at the trough of the recession and reached negative levels in the short period between June and October 2009. However, in the second half of 2009, prices started increasing again, also due to a rise in energy prices. In spite of a persisting level of economic slack, the HICP inflation climbed rapidly and steadily up to a peak of 3% from September to November 2011. Similar developments could be observed in the U.S., where inflation remained stable after a decline in the first months of 2009 and gave rise to a debate on the “missing disinflation”. [4]

If those developments were somewhat surprising for their swiftness, more recent inflation dynamics have displayed a remarkably high degree of persistence. As of 2012, euro area inflation started falling again, and has continued to do so to date. Since October 2013, the year-on-year rate of growth of the headline HICP has oscillated between 1% and 0.5%, in spite of the slowly consolidating economic recovery. A situation of low inflation is now common to many advanced economies, creating a moral general puzzle.

All in all, the lack of a tight relationship between inflation developments and estimates of slack in economic activity, such as the output gap, is not surprising from the point of view of modern monetary theories. The new Keynesian Phillips curve suggests that, net of erratic factors, inflation is determined by the whole path of expected future output gaps, not just its current level. Hence, economic slack at any given point in time need not be associated with a deflationary episode, if it is accompanied by expectations that the output gap will eventually turn sufficiently positive.

In turn, expectations of the future stance of monetary policy play a key role in determining expected future output gaps. The absence of persistent disinflation in 2009 may thus be ascribed to the monetary accommodation imparted by many central banks between the end of 2008 and 2009 through both standard and non-standard tools. The monetary policy easing was commensurate to the size of the shock, i.e. such as to roughly offset the disinflationary pressures produced by the recession. [5]

The recent fall in inflation could equivalently be ascribed to unwarranted fears of a possible tightening of the monetary policy stance not too far into the future.

Such fears could clearly be observed one year ago, when the Federal Reserve announced the tapering of its large-scale asset purchases. In spite of clear Fed communication on the disconnect between this decision and the timing of “lift-off” of policy interest rates, the tapering announcement quickly led to a rise in forward interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic. The ECB’s adoption of forward guidance in July 2013 was largely the result of these unwarranted developments. Recent studies confirm that our forward guidance was successful in reversing the previous increase in forward-rates and in clarifying the persistently accommodative intonation of the ECB policy stance. [6]

The same market logic that led to the interpretation of the Fed’s tapering announcement as a signal of a forthcoming tightening of policy interest rates may also have been applied to interpret the implications of the reduction in the size of the ECB balance sheet that occurred over the past couple of years. From a total dimension equal to over 32.5% of GDP in June of 2012, our balance sheet has shrunk to 19% in May 2014, as a result of banks’ decision to exercise the early repayment option for outstanding 3-year LTROs. The contraction in the ECB balance sheet is particularly striking when compared to the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, which continued expanding from 19% of GDP at the end of 2012 to 25.7 % in May 2014. These developments, which are accompanied by a similar evolution of the respective monetary bases, if jointly interpreted as signals of the relative evolution of future policy rates in the two monetary areas, may have contributed to sustain the appreciation in the exchange rate of the euro which, against the U.S. dollar, went from 1.21 in July 2012 to a peak above 1.39 in May 2014.

The lagged impact of the marked euro appreciation played an important role in determining the recent, low inflation outcomes. Since mid-2012 the exchange rate appreciation is estimated to explain a decrease of 0.5 percentage points in our inflation rate. Together with falling energy and food prices, it explains the bulk of the imported downside pressure on euro area consumer prices.

Of course, the euro appreciation may also have reflected other factors, for example changes in attitudes towards risk. Such factors can be expected to produce only temporary effects on inflation, and would therefore not normally require a monetary policy response. Unwarranted fluctuations in markets’ perceptions over the future stance of monetary policy, however, could be a more persistent source of low-inflation risk. In this case, a monetary policy reaction would be necessary to steer perceptions away from unlikely future outcomes.

How will our recent policy decisions make a difference?

From this standpoint, I believe that there are three clear channels through which the decisions adopted by the Governing Council in June is effective.

The first channel is standard and has to do with the expansionary impact of the measures on the real economy and inflation. To gauge the extent of such an impact, it is useful to refer again to the ECB macroeconomic projections and recall that they are conditioned on a number of technical assumptions. These assumptions relate to the evolution of macroeconomic and financial variables, which specifically include market expectations of short-term interest rates developments over the projection horizon.

The conditioning assumptions for the June 2014 projections were computed based on information available on 14 May 2014. Over the past month, financial market prices have adjusted to reflect the ECB decisions in early June. As a result, expected short-term rates have fallen by 10 basis points at all horizons and the euro has depreciated since May by 2.5% to 1.354. If taken as new conditioning assumptions, these developments would move the whole path of the inflation projections upwards and ensure a faster return to price stability.

The second channel through which the recent ECB decisions will be consequential is the credit channel, which is expected to be positively impacted by the new targeted LTRO facility and the extension of the ACC programme. [7]

The third channel has to do with expectations. The announcement of the measures adopted at the beginning of June has been accompanied by a clear communication concerning the future path of policy.

In his Press conference, President Draghi emphasised again that “key ECB interest rates will remain at present levels for an extended period of time in view of the current outlook for inflation”. He also added that “if required, we will act swiftly with further monetary policy easing. The Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to using also unconventional instruments within its mandate should it become necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation.”

With this statement, the ECB has left no doubts about its resolve to avoid any downward turn in the euro area inflation developments, because such developments would be extremely harmful. With interest rates at their effective lower bound and persistently timid growth prospects, lower than expected inflation rates would increase the real value of debt, slowing down the deleveraging process of borrowers, both public and private. If a low inflation outlook became entrenched in the expectations of firms and households, the real interest rate would rise, leading consumers and investors to postpone their expenditure plans. A vicious circle of lower demand and lower prices could ensue.

How would the ECB react, should the risks of a protracted period of low inflation materialise?

But what exactly could the ECB do in the face of a protracted period of low inflation and economic stagnation?

As I have already mentioned, the ECB stands ready to deploy additional unconventional instruments, should the likelihood of this scenario increase. The policy response would involve a broad-based asset-purchase programme. The experience of other countries with such programmes testifies that they can be effectively designed. As previously mentioned, various empirical studies suggest that the large purchases carried out in the U.S. and in the U.K. were instrumental in decreasing yields by several tens of basis points, with spillover effects on other asset prices, including mortgage rates and exchange rates. In turn, GDP growth and inflation rates also appear to have been significantly affected. After all, even if they have to use new instruments, central banks cannot avoid their responsibility in ensuring price stability, as long as inflation continues to be determined by monetary policy.

Broad-based asset-purchases would allow the ECB to continue pursuing its mandate even under more adverse circumstances. It is however important that other policies also play their part. An extreme adverse scenario that has recently appeared in the public debate is that of a “secular stagnation”. [8] This is effectively a situation where the “natural” long run growth rate of the economy falls significantly and permanently, e.g. because of a fall in the growth rate of population or because of a fall in technological progress, or both. This scenario is only still a possibility, but it is illustrative of a broader need for structural policies to again unleash the growth potential of our economies. Public spending should be redirected towards public investment in infrastructures and education. International trade and labour mobility should be fostered. These are the best recipes to ensure that the secular stagnation will remain a purely academic hypothesis.

Conclusions

Today, I have focused on the low inflation challenges, but let me conclude with a quick reminder that we remain watchful of financial market developments. A necessary condition to ensure the effectiveness of our intended monetary policy stance is to alleviate credit supply constraints. This explains why new targeted LTROs are part of the package of measures decided by the Governing Council in June.

To sum up, the main challenge monetary policy faces in the euro area today is to avert the risk of a prolonged period of excessively low inflation. The ECB has adopted significant new measures in June to ensure a return of inflation to levels closer to 2% and to safeguard the anchoring of medium to long-term inflation expectations. It also has powder left for an additional expansion of the monetary policy stance, in case of downward departures of inflation and inflation expectations from current projections.

-

[1] For a survey of results, see John Williams (2013), President of the San Francisco FED, “Lessons from the financial crisis for unconventional monetary policy” NBER Conference, October. See also Krishnamurthy, A. and A. Vissing-Jorgensen (2013), “The Ins and Outs of LSAPs,” presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Jackson Hole Symposium on the Global Dimensions of Unconventional Monetary Policy; IMF Policy Paper on “Global impact and challenges of unconventional monetary policies”, October; Neely, C. (2013), "Unconventional Monetary Policy Had Large International Effects", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2010-018E, updated August 2013; Joyce, M., M. Tong and R. Woods (2011), “The United Kingdom’s quantitative easing policy: design, operation and impact”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Q3.

-

[2] Quoted by Michael Woodford in his 2012 Jackson Hole paper “Methods of policy accommodation at the interest rate lower bound”

-

[3]See Giannone, D., M. Lenza, H. Pill and L. Reichlin (2011): “Non-standard policy measures and monetary developments”, ECB Working Paper Series No. 1290; De Pooter, M., R.F. Martin, and S. Pruitt (2012): “The effects of official bond market intervention in Europe”, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, mimeo; Eser, F., and B. Schwaab (2013): “The yield impact of central bank asset purchases: The case of the ECB’s Securities Markets Programme”, ECB Working Paper Series No. 1587 and Ghysels, E., J. Idier, S. Manganelli, and O. Vergote (2014): “A high frequency assessment of the ECB Securities Markets Programme”, ECB Working Paper Series No. 1642; Altavilla, C., D. Giannone, and M. Lenza (2014): “The financial and macroeconomic effects of the OMT announcements”, CSEF Working Paper No. 352.

-

[4]See, for example, Coibion, O. and Y. Gorodnichenko (2013), “Is The Phillips Curve Alive and Well After All? Inflation Expectations and the Missing Disinflation,” NBER Working Paper 19598; see also Hall, R.E. (2011), “The Long Slump,” American Economic Review 101, pp. 431–469; and Ball, L. and S. Mazumder (2011), “Inflation Dynamics and the Great Recession,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 337–402.

-

[5]For a formal analysis of this point, see Del Negro, M., M. Giannoni and F. Schorfeide (2013), “Inflation in the Great Recession and New Keynesian Models”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 618.

-

[6]Schwaab, B. (2013): “The impact of the ECB’s forward guidance”, ECB mimeo.

-

[7] The Additional Credit Claims (ACC) programme is an extension of our collateral policy to accept directly loans to non-financial firms as eligible collateral for banks to borrow from the ECB.

-

[8]See e.g. Krugman, P (2013) “Secular Stagnation, Coalmines, Bubbles, and Larry Summers” http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com; Krugman, P. (2014) “Inflation Targets Reconsidered”, presented at ECB Forum on Central Banking, Sintra; Summers, L. (2013) “Remarks at IMF Fourteenth Annual Research Conference in Honor of Stanley Fischer’’; Eggertsson, G. and Mehrotra, N. (2014) “A model of Secular Stagnation”, mimeo.