Update on economic and monetary developments

Summary

Global growth remains modest and uneven. While activity continues to expand at a solid pace in advanced economies, developments in emerging market economies remain weak overall and more diverse. After a very weak first half of the year in 2015, global trade is recovering, albeit at a slow pace. Global headline inflation has remained low and recent additional declines in oil and other commodity prices will further dampen inflationary pressures.

Increased uncertainty related to developments in China and renewed oil price declines have led to a sharp correction in global equity markets and renewed downward pressures on euro area sovereign bond yields. Corporate and sovereign bond yield spreads have widened slightly. The increase in global uncertainty has been accompanied by an appreciation of the effective exchange rate of the euro.

The economic recovery in the euro area is continuing, largely on the back of dynamic private consumption. More recently, however, the recovery has been partly held back by a slowdown in export growth. The latest indicators are consistent with a broadly unchanged pace of economic growth in the fourth quarter of 2015. Looking ahead, domestic demand should be further supported by the ECB’s monetary policy measures and their favourable impact on financial conditions, as well as by the earlier progress made with fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. Moreover, the renewed fall in the price of oil should provide additional support for households’ real disposable income and corporate profitability and, therefore, private consumption and investment. In addition, the fiscal stance in the euro area is becoming slightly expansionary, reflecting inter alia measures in support of refugees. However, the recovery in the euro area is dampened by subdued growth prospects in emerging markets, volatile financial markets, the necessary balance sheet adjustments in a number of sectors and the sluggish pace of implementation of structural reforms. The risks to the euro area growth outlook remain on the downside and relate in particular to the heightened uncertainties regarding developments in the global economy as well as to broader geopolitical risks.

Euro area annual HICP inflation was 0.2% in December 2015, compared with 0.1% in November. The December outcome was lower than expected, mainly reflecting the renewed sharp decline in oil prices, as well as lower food and services price inflation. Most measures of underlying inflation continued to be broadly stable, following a pick-up in the first half of 2015. Non-energy import prices were still the main source of upward price momentum as domestic price pressures remained moderate. On the basis of current oil futures prices, which are well below the level observed a few weeks ago, the expected path of annual HICP inflation in 2016 is now significantly lower compared with the outlook in early December 2015. Inflation rates are currently expected to remain very low or to turn negative in the coming months and to pick up only later in 2016. Thereafter, supported by the ECB’s monetary policy measures and the economic recovery, inflation rates should continue to recover, although risks of second-round effects from the renewed fall in energy price inflation will be monitored closely.

Broad money growth remained robust in November, driven mainly by the low opportunity cost of holding the most liquid monetary assets and the impact of the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme. In addition, lending to the euro area private sector continued on a path of gradual recovery, supported by easing credit standards and increasing loan demand. Nevertheless, the annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations remains low, as developments in loans to enterprises continue to reflect the lagged relationship with the business cycle, credit risk and the ongoing adjustment of financial and non-financial sector balance sheets.

At its meeting on 21 January 2016, based on its regular economic and monetary analyses, and after the recalibration of the ECB’s monetary policy measures in December 2015, the Governing Council decided to keep the key ECB interest rates unchanged. These rates are expected to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time. With regard to non-standard monetary policy measures, the asset purchases are proceeding smoothly and continue to have a favourable impact on the cost and availability of credit for firms and households. More generally, and taking stock of the evidence available at the beginning of 2016, it is clear that the monetary policy measures adopted by the Governing Council since mid-2014 are working. As a result, developments in the real economy, credit provision and financing conditions have improved and have strengthened the euro area’s resilience to recent global economic shocks. The decisions taken in early December to extend the monthly net asset purchases of €60 billion to at least the end of March 2017, and to reinvest the principal payments on maturing securities for as long as necessary, will result in a significant addition of liquidity to the banking system and will strengthen the forward guidance on interest rates.

However, at the start of the new year, the Governing Council assessed that downside risks have increased again amid heightened uncertainty about emerging market economies’ growth prospects, volatility in financial and commodity markets, and geopolitical risks. In this environment, euro area inflation dynamics also continue to be weaker than expected. Therefore, it will be necessary for the Governing Council to review and possibly reconsider the ECB’s monetary policy stance in early March, when the new staff macroeconomic projections – also covering the year 2018 – will become available. In the meantime, work will be carried out to ensure that all the technical conditions are in place to make the full range of policy options available for implementation, if needed.

External environment

Survey indicators suggest that global growth remained modest and uneven at the turn of the year. The global composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) decreased from 53.6 to 52.9 in December 2015 against the backdrop of a slowdown in both the services and manufacturing sectors (see Chart 1). In quarterly terms the global output PMI declined slightly in the fourth quarter relative to the previous quarter. Data point to a sustained growth momentum in advanced economies, with PMIs increasing in the United Kingdom and Japan, although momentum slowed somewhat in the United States. Developments across emerging market economies (EMEs) remain weak overall and more diverse, with the latest PMI data suggesting some strengthening in China, a deceleration in growth in India and Russia, and continued weakness in Brazil in the fourth quarter.

Chart 1

Global PMI

(diffusion index, 50 = no change)

Sources: Markit and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observation refers to December 2015.

Global trade has continued to recover, albeit at a slow pace. Although global trade in the first half of 2015 was very weak, it has since improved. The growth in the volume of global goods imports weakened slightly in October to 1.8% (three-month on three-month), down from 2.3% in September. Import growth momentum strengthened in advanced economies, but the contribution from EMEs decreased, driven principally by lower trade in Latin America. However, early monthly data at the country level confirm that global import growth may have moderated again towards the end of last year. The global PMI for new export orders dipped slightly in December (to 50.6), but remained in positive territory, suggesting continued modest trade growth around the turn of the year.

Global headline inflation has remained low. A less negative contribution from energy prices pushed up slightly annual consumer price inflation in the OECD area to 0.7% in November from 0.6% in the previous month. Inflation excluding food and energy remained unchanged at 1.8%. However, the overall low global CPI inflation masks considerable differences across countries. While headline inflation is low in most advanced economies and also in China, it is considerably higher in some large economies, including Russia, Brazil and Turkey.

Recent additional declines in oil and other commodity prices will further dampen inflationary pressures. Against the background of an oversupplied oil market and weakening oil demand, Brent crude oil prices have undergone a renewed downturn since mid-October 2015, falling to USD 29 per barrel on 20 January 2016. On the supply side, OPEC’s December decision to maintain current production levels at record rates has fuelled the downward dynamics, while non-OPEC output has been more resilient than previously expected, with declining US shale production compensated for by oil supply from Canada, Norway and Russia. Looking ahead uncertainty remains about the impact of the lifting of sanctions against Iran on global oil supply. On the demand side, preliminary estimates showed a steeper than previously expected decline in global oil demand growth in the fourth quarter of 2015 owing to the exceptionally mild winter (in Europe, the United States and Japan) and weaker economic sentiment in emerging markets (China, Brazil and Russia). Oil market participants continue to expect only a very gradual increase in oil prices in the coming years. Non-oil commodity prices have also fallen slightly by 3% since the end of November, driven mostly by decreasing food prices (down by 4%).

US activity growth appears to have softened in the fourth quarter, although underlying fundamentals remain solid. Following a solid expansion of real GDP by an annualised rate of 2.0% in the third quarter of 2015, economic activity showed signs of deceleration in the fourth quarter. Retail sales and vehicle purchases have slowed, and indicators also suggest some weakness in the industrial sectors, with a decline in the Institute of Supply Management manufacturing index. In addition, external headwinds, namely modest global growth and the stronger US dollar, continue to weigh on exports. However, continued strong improvements in the labour market suggest that the underlying strength of the economy persists and that weakness in domestic demand should prove largely temporary. Non-farm payrolls rose sharply in December 2015, with the unemployment rate at 5.0%. Headline inflation remains low. Annual headline CPI inflation rose to 0.5% in November from 0.2% in October on account of a smaller negative contribution from energy prices. Excluding food and energy, inflation edged up slightly to 2.0%, supported by rising services prices.

In Japan, momentum in the economy has been relatively subdued. The second preliminary release revised real GDP in the third quarter of 2015 higher by 0.5 percentage point to 0.3% quarter on quarter. However, short-term indicators point to relatively modest growth in the final quarter of 2015. Although real exports of goods continued to recover in November, declines in retail sales and industrial production in November point to weaker domestic momentum. Annual CPI inflation remained unchanged at 0.3% in November, but annual CPI inflation excluding food and energy rose to 0.9%.

In the United Kingdom, GDP continued to grow at a moderate pace. In the third quarter of 2015 real GDP increased by 0.4% quarter on quarter, less than previously estimated. Economic growth was driven by robust household consumption, in turn supported by the increase in real disposable income, which was driven by low energy prices. Investment growth remained positive, albeit decelerating compared with the previous quarter, while net exports exerted a drag on growth. Short-term indicators, in particular industrial production data and PMI surveys, point towards a steady pace of GDP growth in the last quarter of 2015. The unemployment rate trended downwards, declining to 5.1% in the three months to November 2015, while earnings growth fell to 2.0%, compared with 3.0% in the third quarter of the year. In December 2015 annual headline CPI inflation was close to zero (0.2%) on the back of low energy and food prices, while inflation excluding food and energy edged up to 1.4%.

In China, financial market volatility has led to renewed uncertainty about the outlook, although macroeconomic data remain consistent with a gradual slowdown in activity growth. The Chinese stock market dropped sharply in the first weeks of January, ahead of the expected expiry of a six-month ban on share sales by large shareholders. However, macroeconomic data have been more resilient. China reported quarter-on-quarter growth of 1.6% in the fourth quarter of 2015. Annual real GDP growth in 2015 was 6.9%, close to the government target. Short-term indicators remain consistent with a gradual slowdown in the economy amidst some rebalancing towards services and consumption in the face of subdued industrial output.

Chart 2

Global industrial production growth

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Sources: OECD and national sources.

Note: The latest observation refers to December 2015 for China, to November 2015 for Brazil and Russia, and to October 2015 for OECD countries.

Growth momentum remains weak and heterogeneous across other EMEs. While activity has remained more resilient in commodity-importing countries (including India, Turkey and non-euro area central and eastern European countries), growth remains very weak in commodity-exporting countries. In particular, latest short-term indicators suggest that the downturn in Brazil has intensified. As Box 1 discusses, weak domestic fundamentals and limited support from external factors imply that Brazil will remain in recession this year. The Russian economy showed tentative signs of improvement in the third quarter of 2015 (see Chart 2) but, given the strong dependence on oil, the renewed oil price decline is likely to weigh on the short-term outlook.

Financial developments

Chart 3

Euro area and US equity price indices

(1 January 2014 = 100)

Sources: Thomson Reuters and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observation is for 20 January 2016.

Global equity prices declined significantly amid increasing uncertainty related to developments in China and a sharp reduction in the oil price. The broad EURO STOXX equity price index declined by around 16% over the review period from 2 December 2015 to 20 January 2016 (see Chart 3). Somewhat smaller declines were observed in the United States, where equity prices, as measured by the S&P 500 index, declined by around 12%. Financial sector equities in the euro area and the United States declined by 18% and 13% respectively, thereby slightly underperforming non-financial sector equities. Measures of equity market volatility – an indicator of financial market uncertainty – increased significantly.

The developments in oil and global equity markets led to renewed downward pressure on euro area sovereign bond yields following the increase at the beginning of the review period. Sovereign yields increased after the meeting of the Governing Council of the ECB in December 2015 and fell back somewhat again as global uncertainty increased. Over the review period the GDP-weighted ten-year euro area sovereign bond yield increased by around 15 basis points, to stand at 1.16% on 20 January. The lower-rated countries recorded the strongest increases in general, resulting in a widening of their sovereign yield spread against Germany, which was partly related to financial and political developments.

Chart 4

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro

(indicated currency per euro; percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Percentage changes relative to 20 January 2016. EER-38 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 38 of the euro area’s most important trading partners.

The increase in global uncertainty led to an appreciation of the effective exchange rate of the euro. The euro appreciated markedly in effective terms in the first half of December 2015 as a result of the increase in yields following the December Governing Council meeting. The effective exchange rate of the euro was broadly stable in the period up to mid-January, but started to appreciate again thereafter amid the increase in global uncertainty. Overall, the euro strengthened by 5.3% in trade-weighted terms over the review period (see Chart 4). In bilateral terms, the euro appreciated against the US dollar, the pound sterling, the Chinese renminbi, the Russian rouble and the currencies of emerging market economies – particularly the Argentine peso following the decision by the new Argentine government to lift currency controls. The euro also appreciated against the currencies of commodity-exporting countries and the currencies of central and eastern European countries. By contrast, it depreciated against the Japanese yen, which was supported by the decline in risk appetite.

The increase in global uncertainty also led to higher corporate bond spreads. Spreads increased the most on lower-rated high-yield bonds. However, spreads for both investment-grade and high-yield bonds are significantly lower in the euro area than in the United States. This can mostly be explained by the very high spread levels observed in the energy sector in the United States owing to the low oil prices.

The EONIA declined over the review period following the Governing Council’s decision to cut the deposit facility rate by 0.10% to -0.30% and the continued increase in excess liquidity. The EONIA has remained in a range between -22 and -25 basis points through most of the review period. At the end of the year it temporarily rose to about -13 basis points owing to increased demand for liquidity. During the review period, excess liquidity rose by €62.5 billion to €639.9 billion, supported by ongoing Eurosystem purchases within the expanded asset purchase programme, as well as an allotment of €18.3 billion in the sixth targeted longer-term refinancing operation on 11 December 2015.

Economic activity

The economic recovery in the euro area is continuing, largely on the back of developments in private consumption. Real GDP rose by 0.3%, quarter on quarter, in the third quarter of 2015, following a rise of 0.4% in the previous quarter (see Chart 5).[1] The most recent economic indicators point to a continuation of this growth trend in the fourth quarter of 2015. Although output has now been rising for two and a half years, euro area real GDP still remains slightly below the pre-crisis peak recorded in the first quarter of 2008.

Chart 5

Euro area real GDP, the ESI and the composite PMI

(quarter-on-quarter percentage growth; index; diffusion index)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission, Markit and ECB.

Notes: The Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI) is normalised with the mean and standard deviation of the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2015 for real GDP and for December 2015 for the ESI and the PMI.

Private consumption continues to be the main driver of the ongoing recovery. Consumer spending has benefited from rising real disposable income among households, which in turn primarily reflects lower oil prices and rising employment. In 2015, oil prices fell by slightly more than 35% in euro terms compared with the previous year, while euro area employment rose by 1% (based on data up to the third quarter). In addition to lower oil prices, a broad range of factors, indicative of a strengthened domestic economy, are supporting private consumption. Households’ balance sheets have gradually become less constrained and consumer confidence has remained strong. As for the near-term outlook, recent data on retail trade and new passenger car registrations signal some weakening in consumer spending. This slowdown is assessed to be temporary, however, as it may reflect the dampening impact on retail trade from the mild weather conditions, as well as a negative contribution from French retail sales following the terrorist attacks of November 2015 in Paris. Indeed, survey data on consumer confidence and households’ financial situations suggest continued positive developments in private consumption.

By contrast, investment growth has been weak in 2015, although there are signs of improving conditions for non-construction investment. Investment conditions improved in the last quarter of 2015. According to the European Commission, confidence rose in the capital goods sector and low demand became less of a constraining factor for production. Furthermore, available country data and data on capital goods and construction production point to modest growth during the final quarter of 2015. Looking further ahead, a cyclical recovery in investment is expected, supported by strengthening demand, improving profit margins and diminishing spare capacity. Financing conditions are also improving. Firms’ recourse to external financing has picked up and the most recent survey on the access to finance of enterprises (SAFE) and euro area bank lending survey (BLS) show that financial conditions should act as less of a drag on investment. Nevertheless, the need for further corporate deleveraging in some countries and investors’ reduced long-term growth expectations could serve to moderate the recovery in investment.

Growth in euro area exports continues to remain subdued overall. According to monthly trade data for October and November, exports started to recover towards the end of 2015, standing in these two months 0.4% above the average level in the third quarter. Export growth was likely driven by strengthened growth momentum in advanced economies, with still negative contributions from some emerging market economies. More timely indicators, such as surveys, signal slight improvements in foreign demand and increases in export orders outside the euro area in the near term. Moreover, the depreciation in the euro effective exchange rate in the first half of 2015 continues to support exports.

Overall, the latest indicators are consistent with economic growth in the final quarter of 2015, at around the same rate as in the third quarter. While declining by 0.7%, month on month, in November (following a rise of 0.8% in October), industrial production (excluding construction) still stood 0.1% above its average level in the third quarter of 2015, when it rose by 0.2%, quarter on quarter (Box 2 takes a closer look at differences between industrial production and value added in industry). In addition, both the European Commission’s Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI) and the composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) improved between the third and fourth quarter of last year (see Chart 5). Both indicators rose in December, thus remaining at levels above their respective long-term averages.

Chart 6

Euro area employment, PMI employment expectations and unemployment

(quarter-on-quarter percentage growth; diffusion index; percentage of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, Markit and ECB.

Notes: The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is expressed as a deviation from 50 divided by 10. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2015 for employment, December 2015 for the PMI and November 2015 for unemployment.

The labour market situation is continuing to improve gradually. Employment increased further by 0.3%, quarter on quarter, in the third quarter of 2015, having now risen for nine consecutive quarters (see Chart 6). As a result, employment stood 1.1% above the level recorded one year earlier, the highest annual rise observed since the second quarter of 2008. The unemployment rate for the euro area, which started to decline in mid-2013, fell further in November to stand at 10.5%. More timely information gained from survey results points to further gradual labour market improvements in the period ahead.

Looking ahead, the economic recovery is expected to continue. Domestic demand should be further supported by the monetary policy measures and their favourable impact on financial conditions, as well as by previous progress made with fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. Moreover, the renewed fall in oil prices should provide additional support for households’ real disposable income and corporate profitability, and thus for private consumption and investment. In addition, the fiscal stance in the euro area is becoming slightly expansionary, reflecting, inter alia, measures in support of refugees. However, the economic recovery in the euro area continues to be hampered by subdued growth prospects in emerging markets, volatile financial markets, the necessary balance sheet adjustments in a number of sectors and the sluggish pace of implementation of structural reforms. The risks to the euro area growth outlook remain on the downside and relate, in particular, to the heightened uncertainties regarding developments in the global economy, as well as to broader geopolitical risks. The results of the latest round of the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters, conducted in early January, show that private sector GDP growth forecasts remain broadly unchanged compared with the previous round conducted in early October (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/prices/indic/forecast/html/index.en.html).

Prices and costs

Headline inflation came under renewed downward pressure due to further oil price declines. Positive base effects, due to falling energy prices at the end of 2014, were anticipated to have a strong impact on headline inflation.[2] These were almost offset by the effect of further recent declines in the oil price and by lower food price inflation, with the mild weather contributing to weaker prices for unprocessed food. As a result, headline inflation increased only slightly from 0.1% in November to 0.2% in December.

Chart 7

Contribution of components to euro area headline HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observation is for December 2015.

Most measures of underlying inflation are perceptibly higher than at the turn of 2014/15, but have not picked up further since the summer of 2015. For example, HICP inflation excluding food and energy was unchanged at 0.9% in December, after continuing to move within the range of 0.9% and 1.1% since August. The profiles of most other measures of underlying inflation have been broadly similar. Services inflation decreased in December for the second consecutive month, partly due to the indirect effects of oil price declines on prices for transport-related services. Non-energy industrial goods inflation was unchanged at 0.5%, after recording a broad-based increase in November to its highest level since mid-2013. This stability masked the continued increase in durable goods inflation to 0.9% in December, consistent with the impact of the weaker euro exchange rate and the rise in consumption of durable goods. This increase was offset by a decline in the annual rate of change in prices for semi-durables, in particular clothing, possibly due to the mild weather.

Import prices remain the main source of upward pipeline pressure. The annual rate of growth in import prices for non-food consumer goods rebounded to 3.9% in November, from 3.1% in October. However, domestic price pressures remained weak, reflecting declining commodity input costs and continued moderate wage increases. The annual rate of change in producer prices for domestic sales of non-food consumer goods was unchanged at 0.2% in November, and has remained within the range of 0.0% and 0.2% since April. Earlier in the pricing chain, the annual rate of change in producer prices for intermediate goods continued its decline to -2.0% in November, which was the lowest seen since December 2009. Survey data on input and output prices up to December also point to continued weak domestic pipeline pressures.

Wage growth has remained moderate, while profit margin growth has strengthened. The annual growth in compensation per employee declined to 1.1% in the third quarter of 2015, from 1.3% in the second quarter. Given that the decline in productivity was more modest, the result was a slight decrease in the growth rate of unit labour costs. Wage growth is likely being held back by a range of factors, including continued elevated levels of slack in the labour market, relatively weak productivity growth, and ongoing effects from labour market reforms implemented in past years in a number of euro area countries. The GDP deflator, which provides a broad summary measure of domestic price pressures, remained broadly stable in annual terms in the third quarter due to the fact that the decline in the annual rate of change in unit labour costs was compensated for by a noticeable increase in the annual growth rate of profit margins. Looking through individual quarterly outturns, the annual rate of growth in the GDP deflator has gradually increased since mid-2014.

Looking ahead, on the basis of current oil futures prices, the expected path of annual HICP inflation in 2016 is now significantly lower than that forecast in the December 2015 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. Annual HICP inflation is expected to remain at very low or negative levels in the coming months and to pick up only later in 2016, supported by the impact of monetary policy measures and the expected economic recovery.

Chart 8

Survey-based measures of inflation expectations

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), Consensus Economics and ECB calculations.

Notes: Realised HICP data are included up to December 2015. Consensus Economics forecasts are based on the January 2016 forecasts for 2016 and 2017 and on the October 2015 long-term forecasts for 2018 and 2020.

Indicators of inflation expectations have fallen since the beginning of December against the backdrop of declining oil prices. Following the Governing Council meeting in December, market-based indicators of inflation expectations declined markedly as markets reversed the strong gains made in the days leading up to the meeting. The renewed sharp decline in oil prices in January led to further falls, with most measures returning to the levels observed at the beginning of October. More specifically, the five-year inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead declined from 1.79% to 1.57% between 2 December 2015 and 20 January 2016. Despite low realised inflation and declining market-based inflation indicators, the deflation risk observed in the market continues to be very limited and significantly below the levels seen at the end of 2014 and the beginning of 2015. According to the latest ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), the expected five-year ahead inflation rate edged downwards from 1.9% to 1.8% (see Chart 8). The decline in expectations has been more evident over shorter horizons, reflecting the impact of the renewed decline in oil prices.

Turning to house price developments, annual growth in the ECB’s residential property price indicator for the euro area has increased further. In the third quarter of 2015 the annual rate of change was 1.5%, up from 1.1% in the previous two quarters, suggesting that the recovery is gaining some momentum. It appears to be relatively broad-based across euro area countries but there remains considerable heterogeneity in the magnitudes of growth. The pick-up in house price growth in the euro area as a whole is consistent with improving household income and employment conditions, favourable financing conditions and the correction of previous overvaluations of house prices.

Money and credit

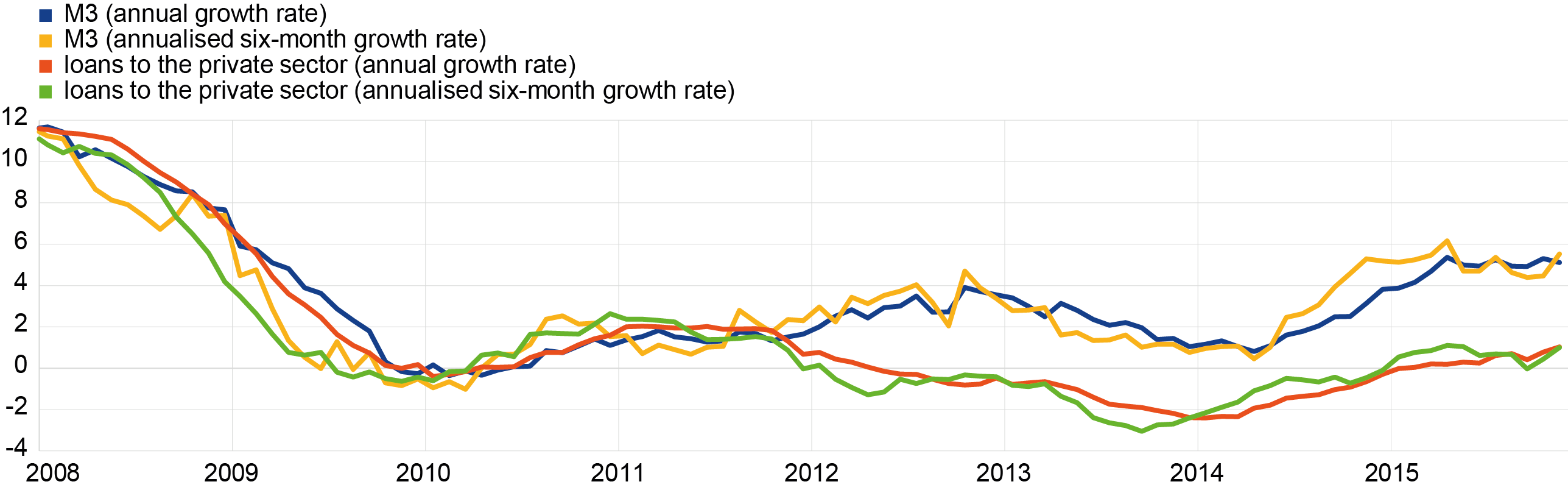

Broad money growth remained robust. The annual growth rate of M3 stayed solid at 5.1% in November, with base effects mainly accounting for the slight decrease from the 5.3% registered for October (see Chart 9). Money growth was once again concentrated in the most liquid components of the narrow monetary aggregate M1, the annual growth rate of which decreased in November while remaining at high levels. Overall, recent developments in narrow money are consistent with a continuation of the economic recovery in the euro area.

Chart 9

M3 and loans to the private sector

(annual rate of growth and annualised six-month growth rate)

Source: ECB.

Note: The latest observation is for November 2015.

Overnight deposits continued to contribute strongly to M3 growth: the main factors behind this growth were the low opportunity costs of holding the most liquid components of money and the impact of the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme (APP). By contrast, short-term deposits other than overnight deposits continued to contract, albeit to a lesser extent than in previous months. The growth rate of marketable instruments (i.e. M3 minus M2), which has a small weight in M3, remained positive, reflecting the recovery in money market fund shares/units observed since mid-2014 and the robust growth of monetary financial institution (MFI) debt securities in the money-holding sector with a maturity of up to two years. The said recovery in money market fund shares/units confirms market resilience to the negative interest rate environment.

Broad money growth was again mainly driven by domestic sources. From a counterpart perspective, the largest source of money creation in November was the bond purchases made by the Eurosystem in the context of the public sector purchase programme (PSPP). In addition, money creation continued to be supported by credit from MFIs to the euro area private sector and the reduction in the MFI longer-term financial liabilities (excluding capital and reserves) of the money-holding sector. This reflects the flatness of the yield curve, linked to the ECB’s non-standard monetary policy measures, which has reduced incentives to hold longer-term assets. It also highlights the Eurosystem’s purchases of covered bonds under the third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3), which reduce the availability of such securities for the money-holding sector. Furthermore, the Eurosystem’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), an alternative source of longer-term funding, have been curbing banks’ issuance activities. The contribution to annual M3 growth made by the MFI sector’s net external asset position remained negative. This reflects capital outflows from the euro area and is consistent with an ongoing portfolio rebalancing in favour of non-euro area instruments (there has been a lower appetite for euro area assets on the part of foreign investors). Euro area government bonds sold by non-residents under the PSPP account for the portfolio rebalancing.

Lending to the euro area private sector continued on a path of gradual recovery. [3] The annual growth rate of MFI loans to the private sector (adjusted for sales and securitisation) increased further in November (see Chart 9), with both loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) and households accounting for the progress. Although the annual growth rate of loans to NFCs remained weak, it has recovered substantially from the trough of the first quarter of 2014. The ECB’s monetary policy measures and further easing of bank credit standards have supported this development. Despite these positive signs, the ongoing consolidation of bank balance sheets and persistently high levels of non-performing loans in some jurisdictions continue to hamper loan growth.

Chart 10

Composite bank lending rates for NFCs and households

(percentages per annum)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The indicator for the composite bank lending rates is calculated by aggregating short and long-term rates using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes. The latest observation is for November 2015.

Bank lending rates for NFCs and households remained broadly stable in November (see Chart 10). Despite recent signs of stabilisation, composite lending rates for NFCs and households have declined by significantly more than market reference rates since the ECB’s credit easing package was announced in June 2014. This development is related to receding fragmentation in euro area financial markets and the improvement in the pass-through of monetary policy measures to bank lending rates. Furthermore, the decline in composite lending rates has been supported by a decrease in banks’ composite funding costs, which stand at historically low levels. Between May 2014 and November 2015, the composite lending rate on loans to euro area NFCs fell by more than 80 basis points to 2.12%. And, over the same period, the composite lending rate on loans to households for house purchase decreased by more than 60 basis points, reaching 2.27% in November. Moreover, the spread between interest rates charged on very small loans (loans of up to €0.25 million) and those charged on large loans (loans of above €1 million) in the euro area decreased further in November. This indicates that small and medium-sized enterprises have benefited to a larger extent than large firms from the recent lending rate developments.

The January 2016 euro area bank lending survey (BLS) suggests that changes in credit standards and loan demand continue to support the recovery in loan growth (see survey at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/money/surveys/lend/html/index.en.html). In the fourth quarter of 2015, banks further eased (in net terms) credit standards for loans to NFCs. There was also a net easing of credit standards for loans to households for house purchase, marking a reversal from previous tightening. Increased competition remained the main factor driving less stringent credit standards. Net loan demand by NFCs and households rose considerably on the back of the low general level of interest rates. Financing needs related to working capital and fixed investment, consumer confidence and housing market prospects were additional factors behind stronger loan demand.

NFCs’ net issuance of debt securities rose modestly in November 2015. The turnaround in net issuance was supported by the observed temporary decline in the cost of market-based debt financing during November. By contrast, the ongoing strong growth of retained earnings has most likely been a dampening factor in recent months. Note that, in the third quarter of 2015, retained earnings still featured a double-digit annual growth rate.

The overall nominal cost of external financing for NFCs is estimated to have increased moderately in December 2015 and in the first half of January 2016. This rise is mainly explained by the higher cost of equity financing (there was a visible decrease in share prices), with the cost of debt financing remaining almost unchanged. In December 2015 and mid-January 2016 the cost of equity and market-based debt financing was, on average, around 40 and 20 basis points higher, respectively, than in November 2015.

Boxes

Box 1 What is driving Brazil’s economic downturn?

Following rapid economic growth in the years preceding the recent global financial crisis, Brazil was in a strong position to weather the Great Recession. Both the commodity price cycle and abundant capital inflows played a role in this improved economic performance. The improvement was also the result of the profound changes in macroeconomic policy management introduced a decade previously, with the end of fiscal dominance and hyperinflation in 1994. However, Brazil’s economic situation has deteriorated significantly in recent years. The economy entered into recession in 2014 and the situation worsened in 2015, with real GDP likely to have declined by 3%, while inflation has remained close to 10%. This box outlines the main factors underlying the economic slump in Brazil.

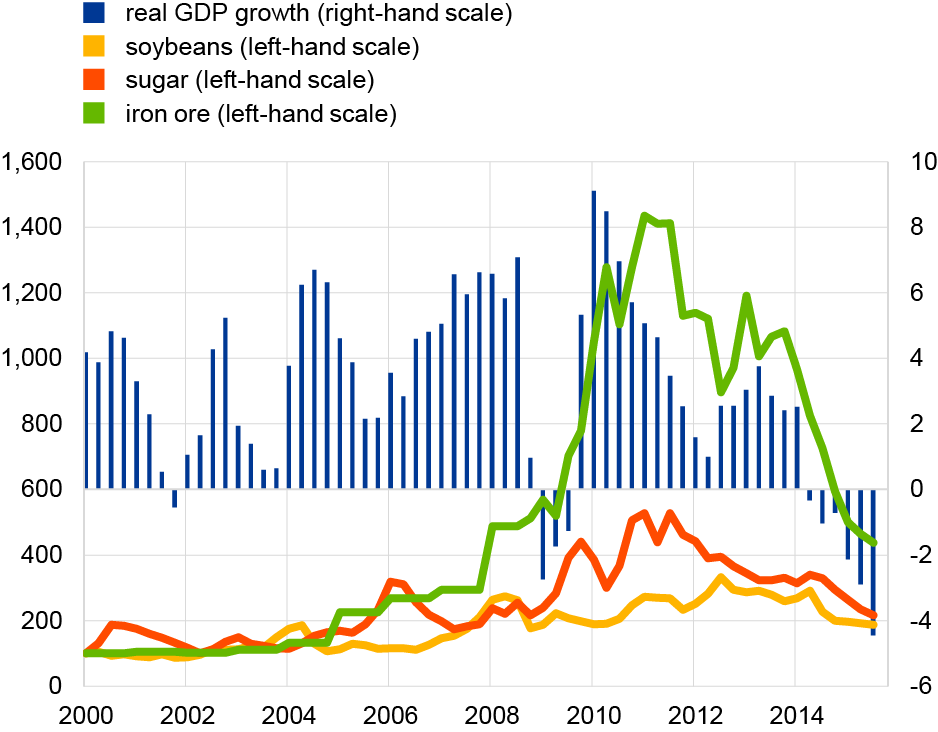

Chart A

GDP growth and major export commodity prices

(left-hand scale: index 2000=100; right-hand scale: annual percentage changes)

Sources: World Bank, CBOT – CME Group and IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica.

The downturn of the non-energy commodity price cycle revealed the underlying structural weaknesses in the Brazilian economy. In the first decade of the century, Brazil benefitted from strong demand – particularly from China – for some of its key export commodities (e.g. iron ore, soybeans and raw sugar). Supported by positive terms of trade effects, Brazil’s annual GDP growth rate averaged 3.1% over this period. Since the fall in commodity prices in 2011 (see Chart A), these terms of trade effects have reversed. As a result, GDP growth has been consistently lower than predicted, while structural weaknesses underlying the economy have resurfaced. These weaknesses include a burdensome tax system, a sizeable informal sector, poor infrastructure, limited competition, the high costs of starting a business and high tariff rates.

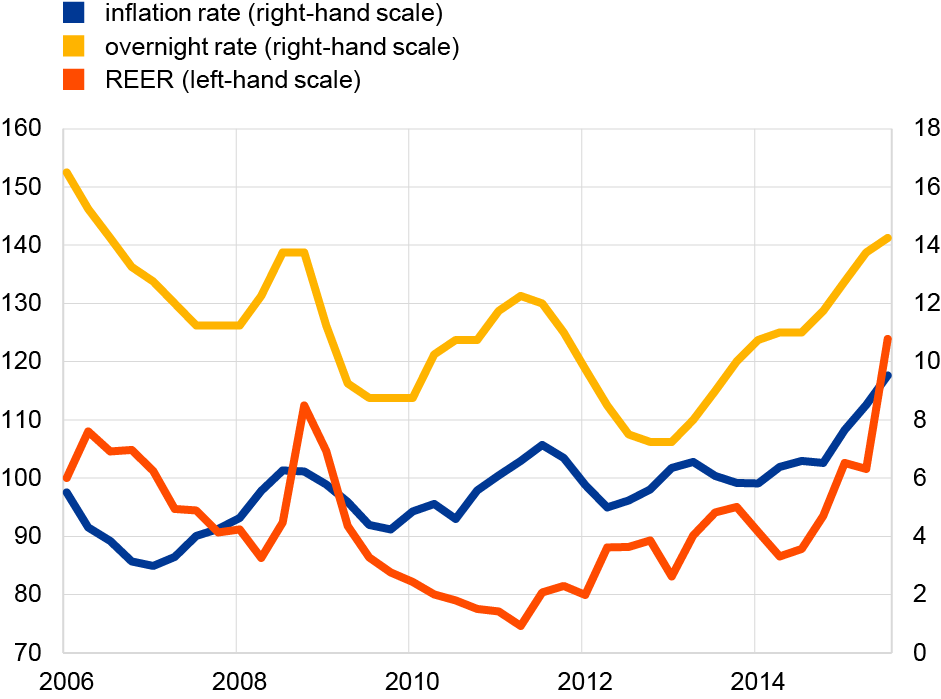

Moreover, imbalances rose amid expansionary policies and strong capital inflows. Around the turn of the decade, Brazil continued to receive strong capital inflows, which amounted annually to around 9% of GDP. While these inflows kept sovereign and corporate spreads low, they fuelled a strong appreciation of the Brazilian real that hurt price competitiveness. Many companies, including large oil companies such as state-owned Petrobras, took advantage of the loose financing conditions to borrow on international markets to finance long-term investments. At the same time, monetary and fiscal policy was expansionary. The official interest rate was cut to a historic low of 7.25% in October 2012 (see Chart B), while subsidised public sector lending, coupled with a rise in tax exemptions to revive business confidence, sharply increased fiscal deficits. Given the lack of structural reforms, however, these measures led to only a moderate and temporary pick-up in GDP growth in 2012-13, while also contributing to rising inflation and a widening of the current account deficit (see Chart C).

Chart B

Inflation rate, overnight rate and real effective exchange rate

(left-hand scale: index 2006=100; right-hand scale: annual percentage changes)

Sources: World Bank, CBOT – CME Group and IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica.

Notes: The SELIC rate is the Brazilian Central Bank's overnight rate. REER stands for real effective exchange rate against 13 main trading partners; increasing values reflect a depreciation of the currency.

Chart C

Total public sector balance and current account balance (relative to GDP)

(percent of GDP, four-quarter moving averages)

Source: IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica.

The shift in global financial market sentiment amid the US Federal Reserve’s announcement that it would wind down asset purchases (the “taper tantrum”) in May 2013 had a significant impact on the Brazilian economy. Global market sentiment suddenly turned against vulnerable emerging market economies with high external and fiscal imbalances, such as Brazil. Despite indications of an impending recession, monetary and fiscal policies were tightened in an attempt to restore macroeconomic credibility. In order to limit capital outflows and support the exchange rate, the Banco Central do Brasil raised its official interest rate to 14.25% in July 2015. On the fiscal front, limits on subsidised lending programs were cut and price subsidies were reduced. At the same time, however, the deterioration in global financial market conditions and the rise in interest rates entailed a surge in interest payments on public borrowing (to around 9% of GDP), which, in turn, raised gross public debt to historical highs (63% of GDP). As the country was unable to generate the fiscal surplus needed to stabilise debt with a sufficiently credible fiscal plan, two rating agencies downgraded Brazil from its investment grade rating for the first time in seven years. Notwithstanding the contraction of Brazilian GDP, inflation surged to over 10% in the last two months of 2015, owing to an adjustment of regulated prices and the sharp depreciation of the currency.

Model estimates suggest that the recent downturn in Brazil is, to a large extent, driven by a combination of domestic factors and lower commodity prices. According to the historical decomposition from a structural Bayesian VAR model[4] (see Chart D), the most significant factors in explaining the decline in Brazilian GDP since mid-2014 have been adverse commodity price developments and shocks to domestic factors, including domestic demand, monetary policy and financing costs. External shocks (defined as global uncertainty shocks and shocks to global financing conditions and foreign demand), on the other hand, have been less significant as a cause of the recent slowdown. In particular, the prices of iron ore and raw sugar – which account for 13% and 5% respectively of total exports – have been falling since 2011, while the price of oil – which accounts for 7% of total exports – has fallen since 2014. As Brazil is still a net oil importer, the main channel through which lower oil prices affect GDP is likely to be investment, rather than purely the terms of trade, as is the case for net oil exporting countries. Total investment has declined by 6% on average since early 2014, partly due to developments at Petrobras, the public oil producer, which accounts for 10% of total Brazilian investment and almost 2% of GDP. The company had to cut investment by 33% in both 2014 and 2015 to adjust to lower oil prices and also in response to a widespread corruption case, triggering confidence effects throughout the economy. The direct and indirect effects of the decline in investment by Petrobras have been estimated by Brazil's Ministry of Finance to have subtracted around 2 percentage points from GDP growth in 2015.

Chart D

Historical shock decomposition of annual real GDP growth

(left-hand scale: median estimates – deviation from long-run mean; right-hand scale: annual percentage changes)

Sources: IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Long-run mean refers to the period from the first quarter of 2000 to the second quarter of 2015.

Looking ahead, the risks facing Brazil remain on the downside amid uncertainties on fiscal policy and political difficulties which might further reduce confidence.

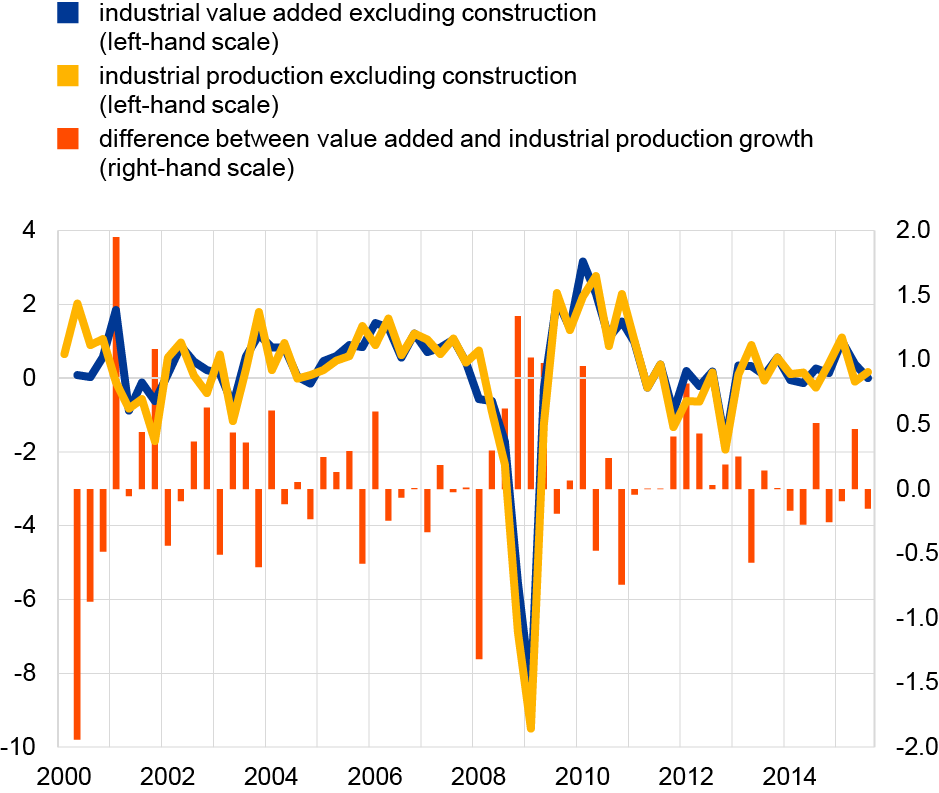

Box 2 A closer look at differences between industrial gross value added and industrial production

Industrial gross value added and industrial production are both very informative indicators of developments in industrial activity. Although conceptually similar, there are a number of differences between the two. [5] Looking at the data available for the latest two quarters, the weakness in euro area industrial production excluding construction in the second quarter of 2015 was not matched by weakness in the corresponding value added (quarterly growth rates were -0.1% versus 0.4%). In the third quarter of 2015, however, industrial production growth provided a more positive picture (growth of 0.2% versus 0.0% for value added). Against this background, this box takes a closer look at the differences between these two indicators for the euro area and explains the methodological differences that give rise to them. Industrial production is a short-term statistic that aims to estimate value added on a monthly basis in order to provide a timely measure of industrial activity. In practice, however, it is difficult to collect value added data on a monthly basis, which means that the monthly change in industrial production is typically derived from other sources, including deflated turnover, physical production data, labour input and intermediate consumption of raw materials and energy. Gross value added Looking at the data available for the latest two quarters, the weakness in euro area industrial production excluding construction in the second quarter of 2015 was not matched by weakness in the corresponding value added (quarterly growth rates were -0.1% versus 0.4%). In the third quarter of 2015, however, industrial production growth provided a more positive picture (growth of 0.2% versus 0.0% for value added). Against this background, this box takes a closer look at the differences between these two indicators for the euro area and explains the methodological differences that give rise to them. Industrial production is a short-term statistic that aims to estimate value added on a monthly basis in order to provide a timely measure of industrial activity. In practice, however, it is difficult to collect value added data on a monthly basis, which means that the monthly change in industrial production is typically derived from other sources, including deflated turnover, physical production data, labour input and intermediate consumption of raw materials and energy. Gross value added[6], on the other hand, is a quarterly national accounts indicator and is measured by subtracting intermediate consumption from output. Industrial production therefore only partly describes the development of industrial value added in terms of volume over a longer period, as the link between industrial production and value added may be affected by changes in input ratios and structures of production.

Movements in euro area industrial value added and production (excluding construction) differ in terms of absolute levels and quarterly growth rates. Chart A plots both indicators of euro area industrial activity in level terms. It shows that for euro area industry excluding construction, the level of value added has, for the most part, been higher than that of industrial production since 2000. This notwithstanding, both indicators tend to show similar cyclical movements in terms of quarter-on-quarter growth (see Chart B), but there have been marked differences of up to 2 percentage points, positive or negative, in some quarters since 2000. The difference between the two growth rates has been 0.1 percentage point on average since 2000. Looking at growth differences in absolute terms, the average as well as standard deviation has been 0.4 percentage point since 2000. This outcome implies that the differences in growth rates seen in the second and third quarter of 2015 were in a range one could expect.

Chart A

Level of euro area industrial value added and production (excluding construction)

(2000=100; gross value added: calendar and seasonally adjusted chain-linked volumes; industrial production index: quarterly average of working day and seasonally adjusted monthly data)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Chart B

Growth in euro area industrial value added and production (excluding construction)

(quarter-on-quarter growth rates; gross value added: calendar and seasonally adjusted chain-linked volumes; industrial production index: quarterly average of working day and seasonally adjusted monthly data; percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Differences in the movements of the two indicators also occur at the euro area country level, but to a varying degree. Among the four largest euro area countries, the difference between the quarter-on-quarter growth in industrial value added and industrial production (excluding construction) since 2000 has been greatest for Spain (0.4 percentage point), France (0.3) and Italy (0.2), but small for Germany (0.03). For five euro area countries this difference in growth over the same period has been negative, most markedly for Ireland and Luxembourg (both -0.6 percentage point). It should be borne in mind, however, that these results are also dependent on the period under investigation. For example, for Germany – where more historical data are available – the slight positive bias in growth rates for the period from 2000 turns slightly negative if the observation period starts in 1991.

In addition to conceptual factors, a number of other factors contribute to the differences between the two indicators, [7] such as seasonal adjustment on an infra-annual basis, as value added is adjusted at a quarterly frequency and industrial production at a monthly frequency. In order to quantify this factor, industrial production data were seasonally adjusted across euro area countries at a quarterly frequency. The outcome, which depends on the parameters applied for the seasonal filters, shows that quarterly growth rates can differ substantially depending on whether the seasonal adjustment is monthly or quarterly (see Chart C). Using data that are seasonally adjusted on a quarterly rather than a monthly basis, the average absolute difference between the growth rates of euro area industrial production is shown to have been 0.5 percentage point since 2000. On average, however, the impact of the other factors remains sizeable.

Chart C

The effects of seasonal adjustment on data measuring growth in euro area industrial production (excluding construction)

(quarter-on-quarter growth rates; percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Prices are treated differently in the two indicators. Gross value added is compiled using basic prices and does not include taxes (less subsidies) on products, whereas industrial production is at factor cost. The difference between value added at basic prices and at factor cost is other taxes (less subsidies) on production, figures for which are not available in volume terms at a quarterly frequency. In addition, whereas gross value added volumes are calculated using annual chain-linking, only a few countries so far apply this for industrial production.

Different economic activities are included in the two indicators. Value added includes water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities (Section E[8]), whereas industrial production does not. The share of this activity in industrial value added excluding construction since 2000 has varied between 4.2% in 2007 and 5.0% in 2009. Chain-linked volume value added series for this sector are only published at an annual frequency and are rather acyclical. Calculations breaking down these annual data into quarterly data indicate that the quarter-on-quarter difference in the growth rate of industrial value added and production remains, on average, at a similar magnitude. Nevertheless, for specific quarters, the impact of Section E is found to be sizeable, i.e. up to 2.2 percentage points during the Great Recession and up to 0.8 percentage point during “normal” times.

A further source of difference between the two indicators is that industrial production typically covers firms above a certain threshold (in terms of turnover or number of employees), with thresholds varying across countries. National accounts attempt to provide a more complete picture by using data from a variety of alternative sources.

All in all, despite the close link between value added and industrial production, the differences between the two indicators reflect all of the above-mentioned factors to some degree, although their relative importance is difficult to assess. From an economic perspective, it is useful to monitor both indicators to assess the economic status of industrial activity. Further harmonisation between national accounts and short-term statistics, as well as between national practices for seasonal adjustment, would help to reduce these differences.

Box 3 Eurosystem publishes more detailed criteria for accepting rating agencies

The Eurosystem has published more detailed criteria that rating agencies must meet to be part of its framework for mitigating financial risk in monetary policy operations. The Eurosystem credit assessment framework or ECAF defines the minimum credit quality requirements that ensure the Eurosystem accepts only assets with high credit standards as collateral. The Eurosystem has a legal obligation to lend money only against adequate collateral.[9] The ECAF also forms the basis of minimum credit quality requirements in the context of outright purchases.

Rating agencies are one source of information in the framework. [10] When rating agencies are accepted under the framework as When rating agencies are accepted under the framework as “external credit assessment institutions” or ECAIs, their ratings are used mainly to assess the credit quality of marketable assets (traded debt instruments, in particular bonds). Rating agencies can also be accepted under the framework as providers of rating tools. In addition, the Eurosystem u“external credit assessment institutions” or ECAIs, their ratings are used mainly to assess the credit quality of marketable assets (traded debt instruments, in particular bonds). Rating agencies can also be accepted under the framework as providers of rating tools. In addition, the Eurosystem uses information from in-house credit assessment systems and counterparties’ internal ratings-based systems. The last three types of credit assessment system are used mainly to assess non-marketable collateral such as credit claims. To ensure that the information provided by all four sources is conses information from in-house credit assessment systems and counterparties’ internal ratings-based systems. The last three types of credit assessment system are used mainly to assess non-marketable collateral such as credit claims. To ensure that the information provided by all four sources is consistent, accurate and comparable, the Eurosystem has established acceptance criteria for each credit assessment source, as well as a harmonised rating scale, against which it regularly monitors the performance of all accepted systems. These procedures aim to protect the Eurosystem against financial sistent, accurate and comparable, the Eurosystem has established acceptance criteria for each credit assessment source, as well as a harmonised rating scale, against which it regularly monitors the performance of all accepted systems. These procedures aim to protect the Eurosystem against financial risks as well as to ensure a level playing field among the credit rating providers.risks as well as to ensure a level playing field among the credit rating providers.

In December 2015 the Governing Council decided to publish further details on the criteria for accepting a rating agency into the ECAF. [11] The published criteria refer to the acceptance of rating agencies as external credit assessment institutions. An agency must, at the time of its application, be providing minimum coverage of assets eligible for use in monetary policy operations in terms of rated assets The published criteria refer to the acceptance of rating agencies as external credit assessment institutions. An agency must, at the time of its application, be providing minimum coverage of assets eligible for use in monetary policy operations in terms of rated assets[12], rated issuers and the volume of assets rated. The rating agency’s coverage must be diversified across the eligible asset classes and across euro area countries. For example, it must rate at least three of the four eligible non-public sector asset classes (covered bonds, uncovered bonds, corporate bonds and asset-backed securities) in two-thirds of the countries. In each asset class it must provide ratings for at least 10% of the eligible assets, 10% of the issuers and 20% of the nominal volume. Moreover, in the three years prior to its application the rating agency must have complied with these criteria at a level of at least 80%.

The requirements are designed to ensure that rating agencies have broad credit risk expertise and a track record over time. For efficiency reasons and in order to ensure that only rating agencies with established and broad credit risk expertise are accepted, the requirements take into account market acceptance of rating agencies’ ratings, the credit risk interlinkages[13] among the eligible asset classes, and the geographical concentration of eligible collateral in the euro area. At the same time, the thresholds are not so restrictive as to preclude the acceptance of new rating agencies: a rating agency assessing around 100 issuers, for example, may comply with the requirements, depending on the geographical and asset-class focus of its business.[14] Furthermore, the set of coverage criteria as a whole is designed to ensure that the Eurosystem has information to ascertain whether a rating agency has an adequate performance track record and to map its ratings to the harmonised rating scale. In addition, the 80% historical coverage requirement over the three years preceding an application allows new rating agencies to benefit from a gradual increase in their European coverage in order to apply to be accepted into the ECAF once they can demonstrate well-established broad credit risk expertise and proven market acceptance.

In the acceptance procedure, the Eurosystem investigates all additional information relevant for risk protection and the efficient implementation of the ECAF. [15] Compliance with the minimum coverage criteria serves only as a prerequisite for the initiation of an acceptance procedure. In view of the importance of the credit quality information for asset eligibility and valuation haircuts, the Eurosystem forms its decision on whether to accept a rating agency on the basis of a comprehensive due diligence assessment. Rating agencies must meet a number of information, regulatory and operational requirements. To be part of the framework they must, for example, be supervised by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). Furthermore, information on their credit ratings needed to monitor rating quality must be available to the Eurosystem. For efficiency purposes and in view of the resource-intensive due diligence process for each individual rating agency, the Eurosystem requires the minimum coverage criteria to be met before it considers accepting a new rating agency.

In addition, the Eurosystem is reinforcing its due diligence to avoid mechanistic reliance on external ratings. It is carrying out additional work to better understand the ratings, rating processes and methodologies of the rating agencies accepted in the ECAF. This is in line with various initiatives by international authorities aimed at reducing over-reliance on external ratings in legal, regulatory and other public frameworks.[16] In parallel, the Eurosystem has enhanced its internal credit assessment capabilities, for example by increasing the number of in-house credit assessment systems for non-financial corporations In parallel, the Eurosystem has enhanced its internal credit assessment capabilities, for example by increasing the number of in-house credit assessment systems for non-financial corporations[17] and by establishing a due diligence process in the context of the asset-backed securities and covered bond purchase programmes. and by establishing a due diligence process in the context of the asset-backed securities and covered bond purchase programmes.

Articles

Article Recent developments in the composition and cost of bank funding in the euro area

Changes in the composition and cost of bank funding have important implications for the provision of credit and, consequently, for economic output and inflation. Banks’ funding costs are affected by monetary policy, but the transmission of policy depends on many factors, including the strength of banks’ balance sheets and the macroeconomic environment. Therefore, developments in bank funding can be different across euro area banks and countries. This article gives an overview of recent developments in the composition and cost of bank funding, including capital, and shows that they varied across the euro area over the period of the financial crisis, which had an impact on the transmission of monetary policy. The interaction between monetary policy measures (both standard and non-standard) and banks’ funding conditions is also discussed.

Introduction

During the financial crisis, a large degree of heterogeneity in the cost of bank credit was linked to a divergence in funding conditions across euro area banks. Understanding banks’ funding conditions is vital for the analysis of credit provision to the real economy and, consequently, of output and inflation, particularly in the light of the fact that funding cost dynamics diverged from monetary policy rates during the crisis.[18] In general, banks seek funding from retail and wholesale sources. Retail funding, i.e. deposits from the private sector, is generally the dominant source of funding, and deposits from the non-financial private sector tend to be less volatile than wholesale funding sources, particularly when protected by deposit guarantee schemes. However, the importance of such sources for a bank’s overall funding depends on institutional features such as the bank’s size or business model. For small euro area banks, in particular, retail deposits account for a considerably larger share of overall funding than wholesale sources.[19] Wholesale funding includes interbank liabilities, which are used for short-term liquidity management, and the issuance of debt securities. Finally, banks also have access to central bank liquidity and raise capital, normally in the form of equity.

A well-functioning banking sector is essential for the effective transmission of monetary policy. This applies in particular to the euro area, where banks play a dominant role in providing external financing to the non-financial private sector. The outbreak of the financial and sovereign debt crisis in 2010 affected all segments of the financial system, especially the banking sector, which hampered the transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy measures to bank funding and, ultimately, to bank lending conditions. Moreover, bank funding conditions were heterogeneous across euro area countries in an environment of sluggish economic activity, high sovereign debt and concerns about weak banks. While differences in funding costs are to be expected, high levels of uncertainty led to excessive risk premia in some jurisdictions and there were periods when banks’ access to wholesale and, to a lesser extent, retail funding was severely hampered. At the same time, the ECB’s non-standard monetary policy measures (such as the policy of full allotment of the liquidity demanded by banks at a fixed rate and the two three-year longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) in late 2011 and early 2012) acted as a strong backstop and prevented a disorderly and forced deleveraging that would have had a considerable negative impact on the overall economy. Since then, steps towards banking union, the ECB’s credit easing package announced in mid-2014, and the expanded asset purchase programme (APP) announced in early 2015 have led to a significant improvement in bank funding conditions, which have become more homogeneous across countries. This has helped to weaken the bank-sovereign nexus, thereby considerably reducing impairments in the transmission mechanism.

The funding and capital structures of banks are of interest for a number of reasons. The determinants of banks’ funding and capital structures are distinct from those of non-financial corporations.[20] Banks are subject to capital regulation because of the significant effect they can have on financial stability and economic growth: given that they are largely funded by deposits, a significant share of which are covered by guarantee schemes, banks are required to hold minimum amounts of capital to absorb losses and mitigate moral hazard concerns.[21] While this implies that the relative cost of equity and debt funding is not the main determinant of banks’ capital structures, it does not mean that their cost is irrelevant. In fact, the cost of capital is an important factor in banks’ portfolio allocation decisions, including lending activity. Recent developments in the European supervisory, regulatory and resolution framework – including macroprudential capital buffers, total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) – help to rectify incentives that are misaligned because of the expectation of public support (the too-big-to-fail problem). The effect of these measures on banks’ cost of funding is a priori unclear, as the direct effect of a reduction in implicit public sector support is at least partially offset by decreased risk-taking by banks. While the transition to the revised regulatory framework may constrain lending in the short term, it is expected to increase economic welfare in the medium to long term, as the negative externalities associated with systemic crises are contained.[22]

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the main developments in the composition of banks’ funding and capital structures and discusses the monetary policy measures that have had an impact on funding quantities, Section 3 discusses developments in the cost of funding and capital and the impact of certain monetary policy measures on these costs, and Section 4 concludes.

The composition of funding and the impact of monetary policy

The structure of banks’ funding and capital is integral to the overall stability and cost of funding. During the crisis, there were changes not only in banks’ overall funding levels, but also in the structure of their funding. This section discusses some of the main changes in euro area banks’ funding over the past decade and compares developments in vulnerable and less vulnerable countries.[23] Banks are defined here as credit institutions and other monetary financial institutions (MFIs) that are resident in the euro area. The impact of monetary policy measures on funding quantities and composition is also discussed.

The composition of euro area banks’ funding has fluctuated over the past decade, reflecting changes in economic conditions, uncertainty and the monetary policy response to the crisis. Banks’ overall funding grew in line with the expansion in their assets until the escalation of the financial crisis following the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the resulting increase in uncertainty in interbank markets. Chart 1 shows annual flows in the main liabilities of MFIs, including capital. Funding flows increased steadily from 2005 until the end of 2007, particularly via wholesale funding sources, which include external (non-euro area) liabilities, interbank funding and shorter-term debt securities and tend to be more volatile than retail deposit funding. While growth in these wholesale funding sources facilitated the fast expansion of banks’ balance sheets in the years leading up to the crisis, the outflows and swift withdrawals observed at the start of the crisis made a significant contribution to bank funding pressures and a reduction in liquidity. Increased reliance on these funding sources is likely to have introduced a pro-cyclical bias in financial intermediation.[24]

Chart 1

Developments in funding of MFIs other than the Eurosystem

(EUR billions; annual flows by quarter)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart highlights three periods: 1. the collapse of Lehman Brothers, 2. the announcement of OMTs, and 3. the introduction of the credit easing package. The analysis is based on aggregate MFI data: deposits from other MFIs include operations between banks belonging to the same economic group. The components constitute MFIs’ main liabilities and exclude money market fund shares/units and remaining liabilities, which are composed mostly of derivatives. Data are annual flows starting in the first quarter of 2005 and ending in the third quarter of 2015. Deposits of MFIs include both interbank funding and funding from the Eurosystem.

Deposits from resident non-MFIs, and deposits from the non-financial private sector in particular, are the most stable and single largest component of funding for euro area banks. While the composition of these deposits varies across countries and bank types, they are the predominant source of funding for banks in both vulnerable and less vulnerable countries.[25] Retail deposits tend to be a more stable source of funding than wholesale sources:[26] since the liquidity services banks provide to depositors can incur transaction and switching costs, retail deposits are less susceptible to unanticipated withdrawals.[27] Moreover, as withdrawals are based on individual liquidity needs they tend to be more predictable, on the basis of the law of large numbers. In addition, deposits are generally insured up to a limit and are less subject to adverse shocks related to uncertainty.

As the financial crisis intensified with the collapse of Lehman Brothers, deposit flows fell, but remained robust relative to the other, more volatile sources of funding in both vulnerable and less vulnerable countries. Since changes in deposit levels are associated with changes in income and general economic conditions, the reduction in flows reflected, at least in part, the deterioration in the macroeconomic environment across the euro area.[28] As the sovereign debt and financial market stress intensified, deposit outflows became more pronounced in vulnerable countries, driven largely by a repatriation of funds by non-domestic depositors (both from other euro area countries and from outside the euro area). After reaching a peak in mid-2012, deposit outflows from vulnerable countries subsided and fragmentation in funding across the euro area receded. This can be explained largely by the ECB’s announcement of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs) and the decision taken at the June 2012 euro area summit by European leaders to deepen European integration in accordance with the long-term objective of creating a banking, fiscal and political union, as well as the decision to launch the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).[29] While deposit flows in vulnerable countries recovered following these announcements, they remained weak relative to pre-crisis levels and then began to decline in an environment of low inflation and subdued income growth. Following the introduction by the ECB of further credit easing measures in the middle of 2014 and the announcement of the expanded APP at the beginning of 2015, deposit flows improved in an environment of increased central bank liquidity.

The sources of wholesale market funding that had increased in the years preceding the collapse of Lehman Brothers decreased rapidly at the start of the crisis, with debt securities issuance and interbank activity in particular slumping (see Chart 1). In vulnerable countries, as interbank funding deteriorated, banks continued to issue securities. A proportion of these were covered by government guarantees, whose aim was to support bank funding over this period.[30] However, issuance diminished as uncertainty and fears regarding the solvency of sovereigns increased. While market risks receded in the middle of 2012, there was a second stage of negative net issuance of debt securities by banks at this time, partly reflecting the correction of excessive leverage of the financial and non-financial sectors, as well as a move towards a more comprehensive regulatory and supervisory framework. Moreover, debt securities funding was replaced by Eurosystem liquidity because the cost of the latter was more favourable. Overall deposit flows from MFIs, which include interbank and Eurosystem funding, decreased as the financial crisis intensified (see Chart 1). Crucially, however, the composition of the deposits changed as more volatile interbank liquidity was partially replaced by central bank liquidity (see Chart 2). Interbank liquidity grew in the years before the financial crisis, reflecting increased international interlinkages among banks as cross-border lending increased over time. With the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the use of interbank deposits as a short-term liquidity tool decreased in line with a need to deleverage and amid general uncertainty about the creditworthiness of counterparties.[31]

Chart 2

Breakdown of MFI deposits at MFIs other than the Eurosystem

(EUR billions; monthly outstanding amounts)

Source: ECB.

Note: The series for the Eurosystem comprises its lending to euro area credit institutions related to monetary policy operations denominated in euro and other claims on euro area credit institutions denominated in euro.