- SPEECH

The effectiveness and transmission of monetary policy in the euro area

Contribution by Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, to the panel on “Reassessing the effectiveness and transmission of monetary policy” at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium

Jackson Hole, 24 August 2024

Introduction

My aim in this contribution is to provide a euro area perspective on the effectiveness and transmission of monetary policy.[1] As expressed in the monetary policy statements of the ECB’s Governing Council, the aim of monetary policy tightening has been to deliver a timely return of inflation to the medium-term two per cent target by dampening demand and guarding against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations. Even if sectoral shocks had played an important role in triggering the initial 2021-2022 inflation surges, monetary policy tightening was necessary in order to contain domestic demand and to signal clearly to price and wage-setters that monetary policymakers would not tolerate inflation remaining above the target for an excessively-long period.[2]

In this contribution, I will report on the transmission of monetary policy, via financial markets and the banking system, to domestic demand and inflation expectations during this tightening episode. My interim conclusion is that monetary policy has been effective in underpinning the disinflation process, with the transmission of monetary tightening operating to restrict demand and stabilise inflation expectations.

The effectiveness and efficiency of monetary policy has required a data-dependent approach to the calibration of the monetary stance. To this end, I will also discuss the importance for the calibration of monetary policy of fully recognising the asymmetric sectoral nature of the pandemic and energy shocks that triggered the initial inflation surges and the impact of sectoral balance sheets on macroeconomic dynamics. These considerations have shaped the monetary policy reaction function of the ECB during this episode, which has been guided by the incoming evidence on: (a) the unfolding inflation outlook; (b) the evolution of underlying inflation; and (c) the strength of monetary transmission (which, inter alia, depends on sectoral balance sheets).

Monetary transmission

Chart 1 shows the evolution of the euro short-term rate (€STR) forward curve since December 2021. In terms of the adjustment in policy rates, there were several distinct phases. Early in 2022, the yield curve shifted up in anticipation of future rate hikes, with the markets anticipating that the ECB would respond forcefully to the building inflation shock. In the second half of 2022, there was an accelerated campaign of outsized hikes in order to move sharply away from an accommodative stance. In the first nine months of 2023, further hikes brought the policy rate to a level that was assessed to be sufficiently restrictive, if held for a sufficiently long duration, to underpin a timely disinflation process. The policy rate was then held at its peak of 4 per cent from September 2023 to June 2024.

Chart 1

Policy rate path and risk-free curve over time

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Notes: “DFR” stands for “deposit facility rate”.The cut-off dates for the data used for the €STR forward curves are 17 December 2021, 16 December 2022, 15 September 2023, and 13 August 2024.

A striking feature of Chart 1 is that the inflation shock triggered a repricing of not only the near-term policy rate path but also the long-term policy rate path. At the end of 2021, the policy rate was expected to remain negative even in 2027 according to market pricing (and expert surveys). The re-pricing occurred in early 2022 and has persisted, with the 2027 (and longer-horizon) policy rate expected to settle in the neighbourhood of two per cent, which is consistent with market views of a near-zero equilibrium real rate and the successful delivery of the inflation target in the medium term.

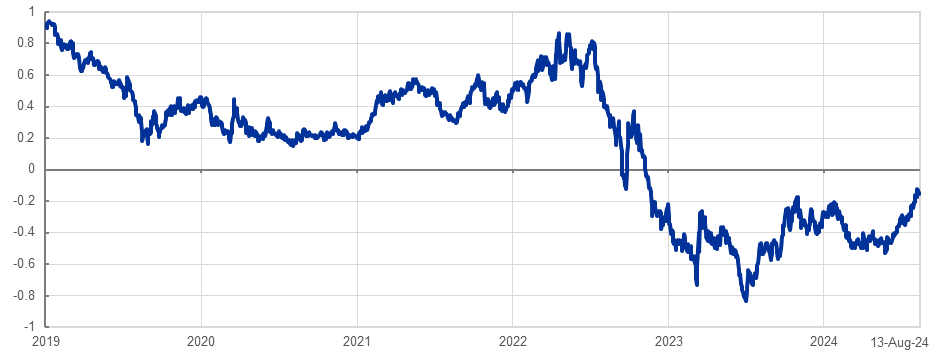

This has meant the inflation shock triggered a fundamental re-setting of the interest rate path, with no expectation of a return to the extraordinarily accommodative monetary stance that had been in place since 2014/2015. At the same time, Chart 2 shows the longer-term yields rose by much less than short-term yields. The negative slope of the yield curve reflects the market assessment that inflation would normalise relatively quickly, such that the cumulative increase in policy rates also had a significant cyclical component that would be unwound. At the same time, this inversion of the yield curve also masked a marked increase in the term premium, including due to the significant decline in the bond market footprint of the Eurosystem (Chart 3): since December 2021, quantitative tightening is estimated to have raised the term premium in the overnight index swap (OIS) curve by about 55 basis points.[3]

Chart 2

Slope of the risk-free yield curve

(percentage points)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Notes: The slope of the risk-free yield curve is calculated as the difference between the ten-year and two-year OIS rates. The latest observation is for 13 August 2024.

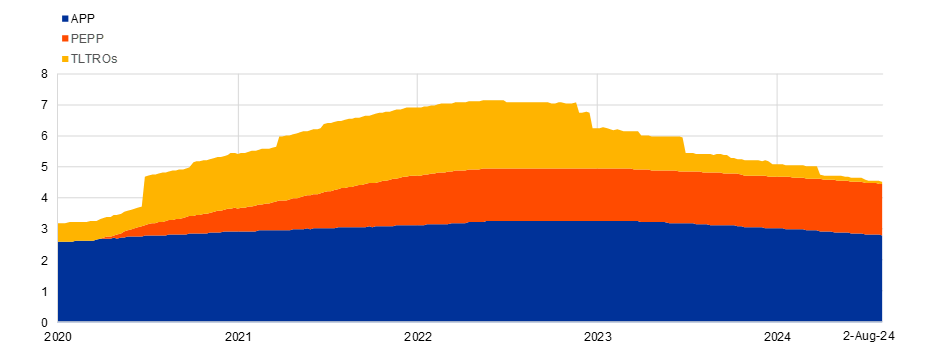

Chart 3

Eurosystem balance sheet

(EUR trillions)

Sources: ECB calculations.

Notes: “APP” stands for “asset purchase programme”, “PEPP” for “pandemic emergency purchase programme” and “TLTROs” for “targeted longer-term refinancing operations”. Purchase programmes are based on book value at amortised cost.The latest observations are for 2 August 2024.

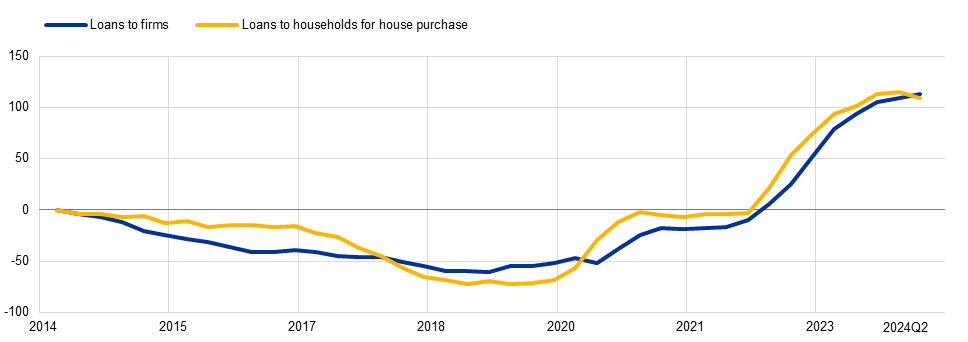

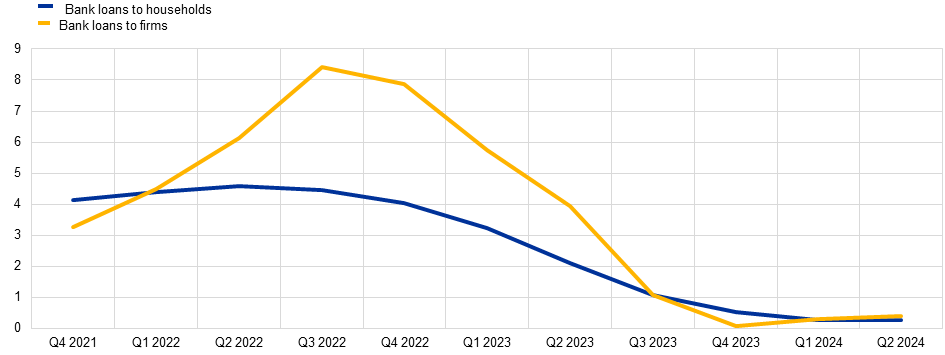

In the bank-based European financial system, the transmission of the restrictive monetary policy stance to bank lending conditions plays a central role.[4] As shown in Chart 4, banks have faced higher funding costs (due to the combination of a rapid increase in bank bond yields and an increase (even if slower) in bank deposit rates) and bank lending rates to firms and households for new loans increased significantly (the prevalence of fixed-rate mortgages has meant that the lending rates facing existing household customers have increased far more slowly).[5] Banks have also tightened their credit standards applied to the approval of loans, as shown in Chart 5.[6] Credit volumes moderated rapidly and nominal credit growth has been very low since 2022, as shown in Chart 6.[7]

Chart 4

Bank lending rates to firms and households, plus bank funding costs

(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB (BSI, MIR, MMSR) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The indicators for the total cost of borrowing for firms and households are calculated by aggregating short-term and long-term rates using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes. The bank funding cost series is a weighted average of new business costs for overnight deposits, deposits redeemable at notice, time deposits, bonds, and interbank borrowing, weighted by outstanding amounts. The latest observations are for June 2024.

Chart 5

Evolution of bank credit standards

(cumulated net percentages of banks reporting a tightening of credit standards)

Sources: ECB (BLS) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Net percentages for credit standards are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages of banks responding “tightened considerably” and “tightened somewhat” and the sum of the percentages of banks responding “eased somewhat” and “eased considerably”. Cumulation starts in the first quarter of 2014.

The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2024.

Chart 6

Credit volumes to firms and households

(annual percentage changes)

Source: ECB (BSI).

Notes: Bank loans to firms are adjusted for sales, securitisation and cash pooling. Bank loans to households are adjusted for sales and securitisation. The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2024.

The decline in credit observed so far in the current cycle has been stronger than historical regularities, based on linear models, would have suggested. The particularly large and rapid increase in policy rates may have amplified the tightening impulse. Moreover, the perceived and abrupt end of the “low for long” era reduced the incentives to search for yield, further contributing to a pullback in risk taking by banks and customers.[8] Large policy rate hikes (including a persistent component) increased the riskiness of borrowers, reducing the willingness to lend. The combination of the war impact and rapid rate hikes also signalled a less positive economic future, reducing the expected revenues and increasing the expected future funding costs of potential borrowers, leading them to reduce their demand for credit.

The dampening of demand

Through the tightening of market-based and bank-based financing conditions, the restrictive policy stance has fed through to economic activity. Chart 7 shows that, the recovery in output over the period 2022-2024 has been much weaker than expected. Despite the impact of the war-related energy shock, the post-pandemic reopening did allow GDP to grow during the first nine months of 2022 (when monetary policy was not yet restrictive). Subsequently, economic activity stagnated between late 2022 and late 2023, with only a limited recovery during the first half of 2024.[9] In terms of demand components, public consumption has been the main consistent driver of growth, while private consumption and external demand have remained subdued in recent quarters (Chart 8). Investment has also been weak: a decline in housing investment has been a persistent drag on growth; while business investment was also hit, the impact was mitigated during 2022-2023 by past order backlogs that somewhat supported the production of capital goods.[10]

Chart 7

Real GDP growth and projections

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat; June 2024, December 2023, December 2022 and December 2021 Eurosystem staff projections; and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for 2023 for GDP and 2024 for projections.

Chart 8

GDP growth contributions

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes and contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2024 for GDP and the first quarter of 2024 for the contributions.

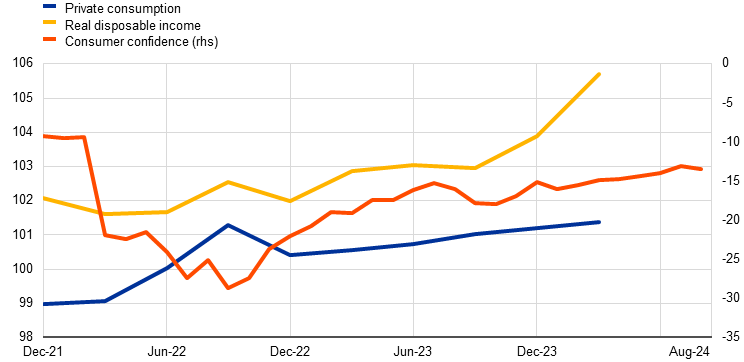

The subdued economic performance is also clearly connected to the uncertainty shock and the energy price and terms of trade shocks triggered by the unjustified invasion of Ukraine by Russia. For instance, Chart 9 shows that, despite the post-pandemic output recovery and strong increase in employment, real disposable income stagnated during 2022 as inflation rose far more quickly than wages. The decline in real incomes would have been more severe in the absence of the countervailing fiscal measures that were widely introduced during 2022 and that boosted transfers to households and suppressed the most intense impact of rising energy prices on households. Indicators of consumer confidence fell at the onset of the war and, despite some gradual improvement, still remain below the pre-war level. Together with the contribution of the restrictive monetary stance, this helps to explain the still-limited response of consumption to the improvement in real disposable income that has been in train since the middle of 2023, due to the recovery in wages, the decline in inflation and the improvement in the terms of trade.

Chart 9

Private consumption, real disposable income and consumer confidence

(left scale: index Q4 2019 = 100, right scale: net percentage balance)

Sources: Eurostat and European Commission.

Notes: The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024 for private consumption and disposable income, and August 2024 for consumer confidence.

Put differently, the adverse war-related 2022 shocks to household incomes, the terms of trade and confidence indicators for both households and firms served as countervailing influences on demand conditions and thereby reduced the extent of demand dampening that needed to be generated by monetary tightening.

While employment growth also decelerated, it remained above the rate of output growth. Unemployment has remained broadly stable at a historically-low level, with employment growth accommodated by an increase in the labour force through a mix of rising participation and a recovery in immigration. This robust labour market performance (which has also mitigated the impact of rising interest rates on consumption) reflects the composition of activity, with services (including public services) more robust than manufacturing. It also reflects labour hoarding, with the anticipation of future recovery motivating firms to retain workers. In turn, labour hoarding was supported in 2022-2023 by strong profitability levels, the decline in real wages and the rise in interest rates (such that the relative price of labour versus capital declined). The moderation in the labour market in 2024 is consistent with a weakening of these forces, with profitability declining, real wages rising and a turn in the interest rate cycle.

Monetary policy affects demand and prices through multiple channels: someare more direct (via intertemporal substitution) and others are more indirect (via growth and employment). This means that the full impact of changes in monetary policy on aggregate inflation occurs only with long and variable lags. As consumers rein in their spending in response to monetary policy tightening, they start by consuming fewer goods with a high intertemporal elasticity of substitution, such as durables and non-essential items. They also reduce spending on goods that are more interest-rate sensitive, such as durable goods purchased using credit, including housing. Analysis by ECB staff suggests that the peak price response of items most sensitive to monetary policy shocks, which tend to include durables and non-essential items, is around three times larger than for less sensitive items.[11] The price reaction to monetary policy shocks of these more sensitive consumer items has been stronger in the recent tightening cycle than in past episodes of monetary restraint, reflecting the effectiveness of the steep and decisive hiking policy in dampening demand.

In summary, monetary tightening has restricted domestic demand, especially since late 2022. A dampened-demand environment directly reduces the capacity of firms to raise prices and workers to obtain wage increases. It also contributes to the stabilisation of inflation expectations, to which we now turn.

The anchoring of inflation expectations

A primary task for monetary policy in the disinflation process has been to ensure that the large pandemic and sectoral shocks did not translate into an increase in the medium-term inflation trend by fostering an upward de-anchoring of inflation expectations that could persist even after the unwinding of the sectoral shocks. In particular, the very sharp rise in actual and projected inflation in the course of 2022 put a premium on guarding against the de-anchoring of inflation expectations and motivated an accelerated approach to monetary tightening between July 2022 and March 2023, with the policy rate hiked by 350 basis points over six meetings.

In the post-crisis years before the pandemic, expectations had become de-anchored to the downside. The pre-pandemic distribution of long-term inflation expectations in the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) was skewed to the left, as shown in Chart 10, and had a median expectation of 1.7 per cent. A similar pattern was evident in market-based indicators.[12] Between the middle of 2021 and early 2022, there was a remarkable shift in long-term inflation expectations, with survey respondents moving away from the long-held views that inflation would remain below two per cent indefinitely.[13] In essence, the majority of respondents assessed that the inflation shock opportunistically served to re-anchor long-term inflation expectations at the target by demonstrating that target risks were two-sided.[14] This is in line with the behaviour of market interest rates shown in Chart 1: the re-anchoring of medium-term inflation expectations has removed the need for an open-ended accommodative underlying monetary stance.

Chart 10

Survey of Professional Forecasters: distribution of longer-term inflation expectations

(percentages of respondents)

Sources: SPF and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical axis shows the percentages of respondents; the horizontal axis shows the HICP inflation rate. Longer-term inflation expectations refer to four to five years ahead. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024.

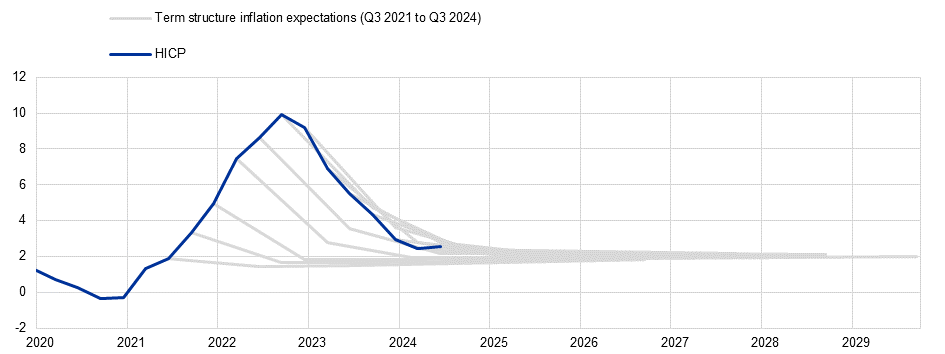

Reinforced by the target-consistent monetary policy decisions during this period, the stabilisation of medium-term inflation expectations has provided an important anchor in the disinflation process.[15] The sheer magnitude of the inflation surge, the successive upward price shocks and the shifts in the short-term inflation outlook clearly could have generated upside de-anchoring risks. Instead, as shown in Chart 11, throughout this period the high-inflation phase has been expected to be relatively short-lived, supporting the timely return of inflation to the target. As shown in Charts 12 and 13, there has also been a decline in the medium-term inflation expectations reported by firms in the survey on the access to finance of enterprises (SAFE) and by households in the Consumer Expectations Survey (CES).

Chart 11

Term structure of inflation expectations from professional forecasters

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, SPF and ECB calculations.

Notes: The term structure of inflation expectations shows expectations for different horizons in past rounds of the SPF.

Chart 12

Consumer Expectations Survey

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and CES.

Notes: The series refer to the median value. The latest observations are for July 2024.

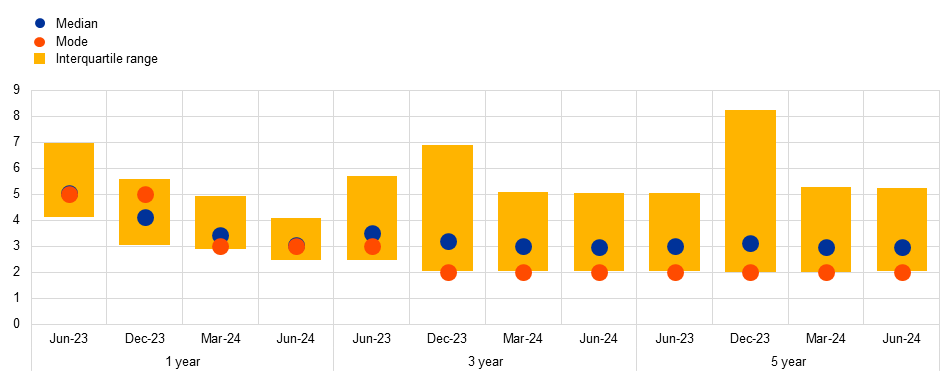

Chart 13

Firms’ expectations for euro area inflation at different horizons

(annual percentages)

Sources: SAFE and ECB calculations.

Notes: Survey-weighted median, mode and interquartile ranges of firms’ expectations for euro area inflation in one year, three years and five years. Quantiles are computed by linear interpolation of the mid-distribution function. The statistics are computed after trimming the data at the country-specific 1st and 99th percentiles. Base: all enterprises.

In turn, the anticipation of the monetary policy response helped to reduce the scale and duration of the inflation response to the large shocks. This anticipation effect was plausibly stronger during this episode, since the large shocks in 2021 and especially 2022 triggered an increase in the frequency of price adjustment.[16] A monetary policy stance that is clearly committed to the timely return of inflation to the target is especially powerful under state-dependent pricing.[17] An increase in the frequency of price changes represents both an extra cost from high inflation (since there are economic costs – including management costs – from adjusting prices more frequently) but also an opportunity: if price setters understand that the central bank is committed to returning inflation to the target in a timely manner through an aggressive interest rate response to the large shock, the phase of intense inflation will be shorter and the sacrifice ratio in terms of lost output will be lower since price setters only have to focus on adjusting prices to the cost shock rather than also having to incorporate an excessively-prolonged aftershock phase of second round effects.

In summary, the risk of an upside de-anchoring of inflation expectations has been contained. This has certainly been facilitated by the nature of the initial inflation shocks, with the relative price shifts triggered by the pandemic and the war-related energy shock reversing fairly quickly and disinflation being further supported by the innate demand-dampening characteristics of the war and the terms of trade deterioration. The historical evidence and model-based counterfactual analyses clearly indicate that an insufficiently -vigorous monetary policy response could have resulted in a persistent increase in the inflation trend. At the same time, the calibration of the monetary policy response also needed to contain the risk of returning to the downside-deanchored equilibrium that had prevailed in the euro area before the pandemic.

Sectoral shocks and disinflation dynamics

During the disinflation process, the calibration of monetary policy needed to take into account the reversal in energy inflation, the easing of pipeline pressures and the relaxation of supply bottlenecks. The pandemic and the subsequent energy shock triggered by Russia’s unjustified invasion of Ukraine had asymmetric and time-varying effects on different sectors. During 2020 and 2021, the impact of the pandemic on activity was most severe for contact-intensive services, while the goods sector was overwhelmed by the mismatch between a positive global demand shift and a decline in global supply capacity due to pandemic-related shutdowns and supply-chain interruptions. During 2022, the dislocations in the oil and gas sectors due to the Russia-Ukraine war were associated with an extraordinary surge in energy prices, which also constituted a severe terms of trade shock for the euro area as a net energy importer. In Europe, the full relaxation of pandemic-related lockdown measures also occurred only in spring 2022, after the subsidence of the Omicron variant. Accordingly, in 2022, the mis-match in the goods sector was succeeded by a mis-match in the services sector, with demand for contact-intensive services rising more quickly than supply capacity in the immediate aftermath of the full post-pandemic reopening that spring.

Subsequently, the improvement in supply capacity and the unwinding of the adverse terms of trade shock has both supported economic activity and contributed to disinflation. In particular, the normalisation of demand and the expansion in supply capacity reduced these sectoral mismatches. After peaking in 2021, supply chain bottlenecks gradually eased during the course of 2022 and 2023, contributing to a decline in the relative price of goods. The decline in energy demand and the increase in energy supply capacity, together with the contribution from the various subsidy schemes that limited the impact of the shocks on retail energy prices, meant that energy prices fell by 14 per cent between their peak in October 2022 and July 2023.

The easing of bottlenecks and the decline in the relative price of energy also helped to calm food inflation and, via lower cost pressures, services inflation.[18] In addition, the reversal of the adverse supply shocks also boosted activity and employment, with the fading of the pandemic in particular supporting activity in 2021 and 2022, and falling energy prices and the receding impact of past bottlenecks boosting activity in 2023 and 2024. Compared to a purely demand-driven inflation episode, the nature of this inflation shock limited the extent to which disinflation would necessarily be accompanied by a severe economic contraction: rather, the aim of monetary policy was to make sure that demand grew more slowly than supply capacity during the disinflation phase.

The euro area implementation of the Bernanke-Blanchard model provides a useful organising device to represent the contribution of sectoral shocks.[19] The left panel of Chart 14 shows that shocks to energy and food prices, together with pandemic-related shortages, accounted for the largest part of the 2021-2022 inflation surges and the subsequent disinflation can largely be attributed to the fading of these shocks. In contrast, labour market tightness has played a comparatively minor role in inflation dynamics.

The right panel of Chart 14 shows that the phase of above-target inflation has primarily been prolonged by the lagged adjustment of wages (and prices) to the initial inflation shocks. The aim of monetary tightening has been to contain this adjustment phase by making sure that the post-shock rounds of wage and price adjustments were limited by dampened demand and underpinned by stable longer-term inflation expectations.

Chart 14

Sectoral shocks

HICP inflation | Negotiated wage growth |

|---|---|

(year-on-year growth rate, pp contributions) | (year-on-year growth rate, pp contributions) |

|  |

Source: ECB calculations based on Arce, O., Ciccarelli, M., Kornprobst, A. and Montes-Galdón, C. (2024), “What caused the euro area post-pandemic inflation?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 343, ECB.

Notes: The figures show decompositions of the sources of seasonally adjusted annual wage growth and HICP inflation based on the solution of the full model and the implied impulse response functions. The out-sample projection is constructed by performing a conditional forecast starting in Q1 2020, conditional on realised variables between Q1 2020 and Q1 2024 and technical assumptions and inverted residuals between Q2 2024 and Q4 2026 such that HICP in the conditional projection is equal to the seasonally adjusted June 2024 Eurosystem staff projections. Assumptions from the June 2024 projections baseline correspond to energy and food price inflation and productivity growth. Labour market tightness is assumed to remain constant. The “shortages” (measured by the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index) are known up to Q2 2024 and projected according to an AR(3) process thereafter. The historical decomposition treats the projection as data and is carried out from Q1 2020 onwards to compute the contributions of the initial conditions and of the exogenous variables.

According to this analytical framework, the bulk of disinflation could be expected to take place relatively quickly with the fading of the sectoral shocks, but full convergence back to the target would be slower due to the lagged nature of wage adjustments and the staggered pattern of economy-wide price adjustments to cost increases. In turn, these characteristics of the disinflation process (an initial rapid phase, followed by a slower convergence phase) have informed the calibration of monetary tightening.

The nature of the disinflation process has been recognised in the Eurosystem staff projections. For instance, the December 2022 projections foresaw that inflation would decline from the quarterly peak of 10 per cent in Q4 2022 to 3.6 per cent in Q4 2023, 3.3 per cent in Q4 2024 and 2.0 per cent in Q4 2025. Disinflation turned out to be even more rapid during 2023, with Q4 inflation at 2.7 per cent. The June 2024 projections foresee inflation at 2.5 per cent in Q4 2024 and 2.0 per cent in Q4 2025.

In summary, diagnosing the nature of inflation dynamics has been essential in calibrating monetary tightening. Conditional on inflation expectations remaining anchored, the fading out of the initial shocks that triggered the steep rise in inflation could be expected to deliver a two-phase disinflation process, with an initial steep decline followed by a slower convergence phase as wage-price and price-price staggered adjustment dynamics played out.[20] The role of a demand-dampening monetary stance has been to make sure that inflation did not remain too far above the target for too long and to reinforce the commitment to a timely return to the inflation target, such that price and wage-setters could focus on “backward” adjustment dynamics – aimed at recovering lost purchasing power and re-establishing optimal relative prices – without worrying about the “forward” adjustment dynamics that would be generated by any de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

Sectoral balance sheets

In calibrating the monetary stance, it is also essential to take into account that the impact of monetary policy depends on the condition of sectoral balance sheets. These encompass the balance sheets of firms, households, banks, the public sector and the rest of the world.[21]

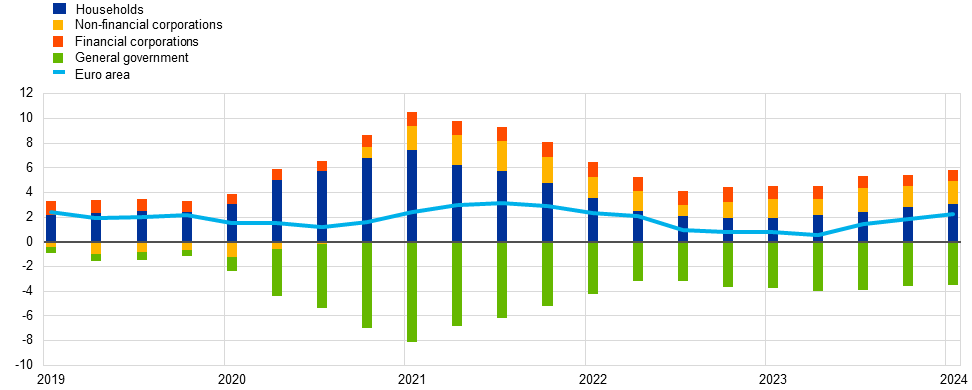

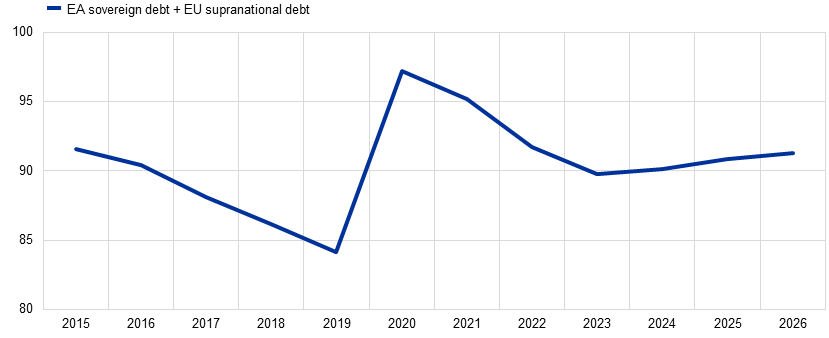

Chart 15

Euro area net lending / net borrowing

(as a percent of nominal GDP – four quarter sums)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB.

Note: The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024.

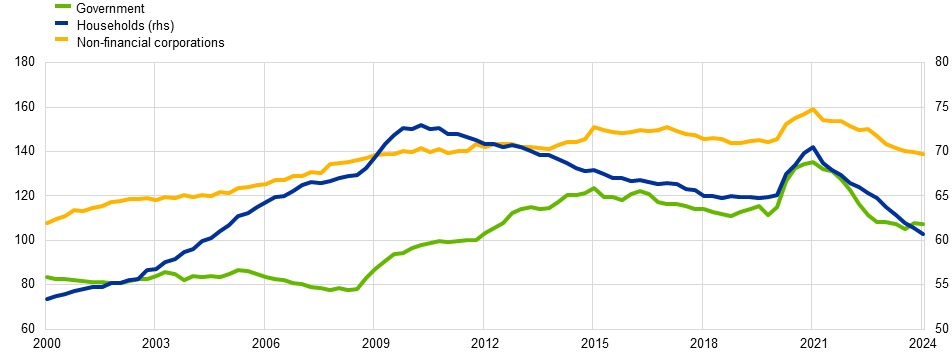

Chart 16

Sectoral leverage

(percentages of nominal GDP – four-quarter sums)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Note: Leverage is defined as total non-equity liabilities divided by the four-quarter sum of nominal GDP.

The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024.

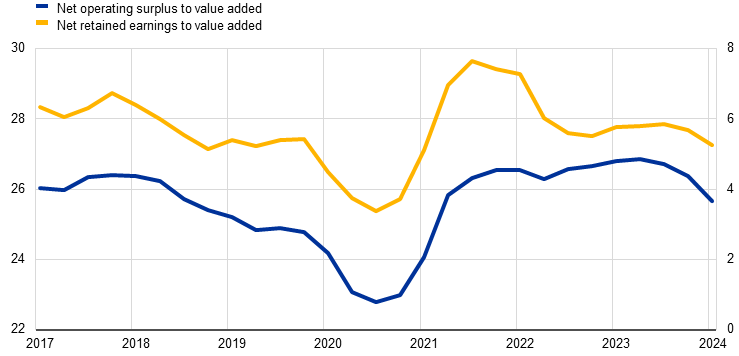

Chart 17

Non-financial corporations’ margins and saving ratio

(percentages – four quarter moving averages)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024.

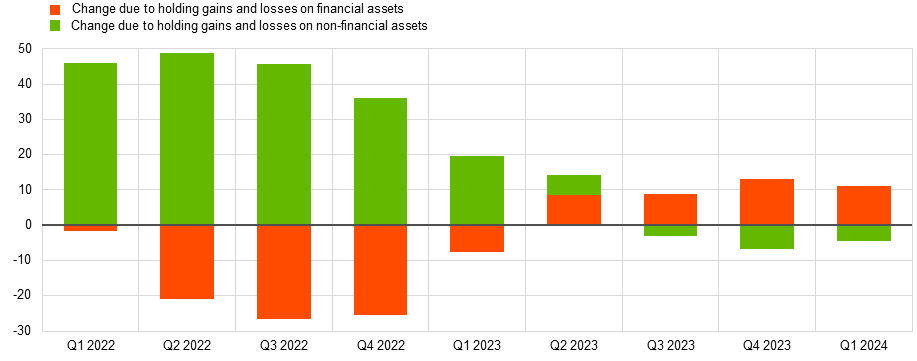

Chart 18

Net worth of households

(annual changes as percentages of nominal disposable income)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Note: Changes are mainly due to movements in real estate and share prices. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024.

Chart 15 shows that households had exceptionally high savings rates in 2020 and 2021. While firms were net borrowers during the initial months of the pandemic in 2020, corporate debt was contained by significant fiscal transfers and de-risked through extensive public loan guarantees. Taking a longer-term perspective, Chart 16 shows that household leverage before the pandemic had declined relative to the 2010 peak but was still elevated compared to the initial years of the euro; although there had been some decline since 2016, the pre-pandemic level of corporate leverage was much higher than at the start of the euro.

While the collapse of GDP meant that these leverage ratios jumped during 2020, both now stand well below their pre-pandemic levels, also due to the significant rise in nominal GDP. These balance sheet improvements have helped to cushion the financial impact of monetary policy tightening on households and firms. In addition, the trend shift towards fixed-rate mortgages also meant that fewer euro area households faced an immediate cash flow burden due to higher mortgage servicing costs. Moreover, in contrast to an inflation scenario in which the unwinding of a demand shock means that monetary tightening is accompanied by economic contraction, the improvement in supply capacity after the pandemic, the easing of bottlenecks and the 2023-2024 unwinding of the 2021-2022 energy shocks meant that there was underlying positive momentum in employment and output. This further contained credit risk premia, in contrast to tightening cycles triggered by excess demand episodes (often accompanied also by financial excess). One illustration is provided by Chart 17, which shows that corporate profitability was above the pre-pandemic level in 2021 and 2022, also boosted by prices adjusting more rapidly to the inflation surge than wages. While the monetary tightening and rising labour costs have seen a decline in corporate profitability, it only just returned to the pre-pandemic level in early 2024.

At the same time, the financial exposure to rising interest rates that was embedded in the holdings of non-bank financial intermediaries was ultimately held either by euro area households or the global investor community. Chart 18 shows that housing assets served as a partial inflation hedge during 2022 even if higher interests rates resulted in some reversal in valuations in 2023. At the same time, there were net capital losses on household financial portfolios during 2022. The sharp increase in inflation also eroded the real value of household deposits. The losses on financial portfolios are likely to have been disproportionately absorbed by higher-income households with relatively low marginal propensities to consume, with cushioning provided by the high share of this group in pandemic-era excess savings.[22]

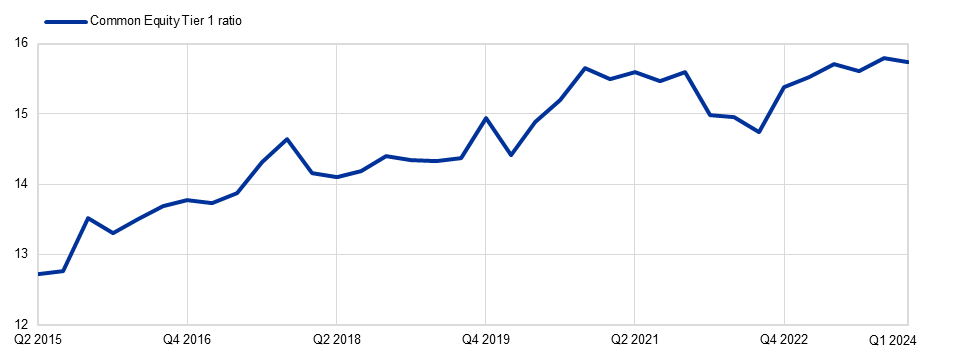

In the aftermath of the 2008-2012 global and euro area crises, the resilience of the euro area banking system has been improved through a mix of higher regulatory requirements, more intensive bank supervision, the rolling-out of more extensive macroprudential regulations and greater managerial risk aversion. As an illustration, Chart 19 shows the marked improvement in capital ratios in the banking system between 2015 and 2019. Simultaneously, liquidity ratios improved significantly, further increasing the overall resilience of the banking sector. Pandemic-related excess savings by households, extensive fiscal transfers to households and firms, public loan guarantees, the reversal of the pandemic and energy shocks and low-cost funding from the ECB meant that banks did not suffer significant credit impairments during the 2020-2021 period.

Chart 19

Capital ratio of the banking system

(percentages)

Source: ECB supervisory reporting.

Notes: The sample consists of significant institutions under the supervision of the ECB (changing composition). The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2024.

Chart 20

Gross debt

(percentage of euro area GDP)

Source: June 2024 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections.

Notes: Supranational EU debt (not reflected in the euro area aggregate) is the gross outstanding debt of the EU institutions, including Next Generation EU financing. Supranational EU debt is not an official statistic, but an internal estimate.

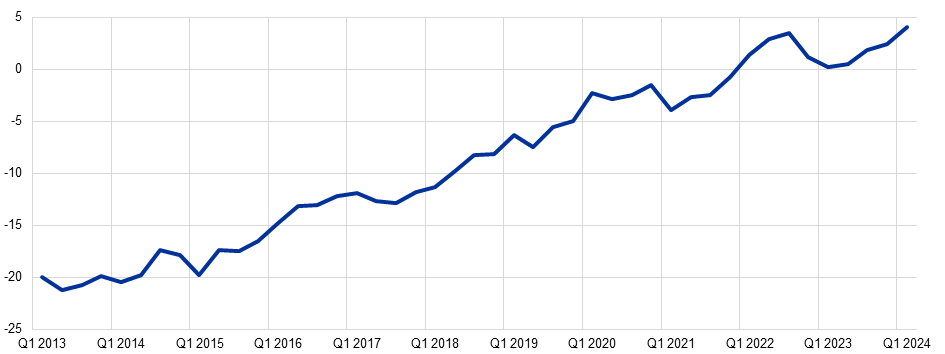

Chart 21

Euro area net international investment position

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB (balance of payments) and Eurostat (national accounts).

Note: The latest observation is for the first quarter of 2024.

The robust state of bank balance sheets meant that the transmission of rate hikes to banks could proceed in an orderly manner. In particular, the increases in risk-free rates were not amplified by an outsized increase in credit risk premia or a severe contraction in credit supply. Moreover, the capital losses on the bonds held by the banking sector were contained by the relatively low bond allocation in the asset holdings of euro area banks.[23] In a related manner, the high share of central bank reserves in the asset holdings of banks meant that the overall duration risk was relatively limited. Bank profitability improved substantially due to the shift to a higher interest rate environment and was further bolstered by the increase in interest paid on central bank reserves.[24] In effect, the resilience of the banking sector, together with the highly-liquid composition of bank assets, has increased the feasible monetary policy space by muting concerns about the financial stability impact of rate hikes.[25] The highly-liquid state of the asset side of bank balance sheets meant that losses from fixed rate mortgage assets were compensated by rising income from central bank reserve holdings.

While the level of central bank excess reserves in the euro area remains high at around €3.1 trillion, these have declined by more than a third, or €1.7 trillion, since the peak reached in the second half of 2022. This has mostly been the result of the repayment of funding from targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO), which fell from €2.2 trillion in June 2022 to a mere €76 billion in July 2024 and will reach zero in December 2024.[26] The reinvestment of the asset purchase programme (APP) portfolio stopped in June 2023, with the APP portfolio dropping from a peak of €3.3 trillion in June 2022 to €2.8 trillion in July 2024. The pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) portfolio started to shrink in July, with the intention to discontinue reinvestments altogether at the end of this year.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the transition from a high-reserves environment to a lower-reserves environment can trigger a shift in the risk-taking strategies of banks (vis-a-vis both lending and bond purchasing), in relation to a decline in the stock of reserves that might have been expected to remain in the banking system for an extended period as the funding counterparts to asset purchase programmes or long-term refinancing operations (sometimes described as “non-borrowed” reserves).[27][28][29]

Directionally, this contraction in liquidity may have contributed to the relatively-strong decline in lending volumes in the euro area during this tightening episode. In particular, estimates by ECB staff suggest that banks with lower excess liquidity are more likely to reduce their supply of credit in response to policy rate hikes, and the increase in their lending rates is likely to be larger. This means that, as aggregate liquidity shrinks, the transmission of the restrictive monetary policy stance to bank lending may strengthen further.

The counterpart to the insulation of household, bank and corporate balance sheets during the pandemic was an expansion in sovereign debt (see Chart 20). The surprise inflation, together with the output recovery, has partially offset the increase in debt-output ratios but these remain above their pre-pandemic levels. In addition, the considerable fiscal response to the energy shock in 2022 increased public debt levels, even if many of these temporary measures have now been reversed. Naturally, an integrated view of the consolidated public sector balance sheet should take into account the decline in the net equity position of central banks but any evaluation of the impact of monetary tightening via this channel will depend on the specification of the relevant counterfactual scenario.

Despite some volatility episodes, the combination of higher policy rates, quantitative tightening and an increase in public debt levels has not triggered a substantial increase in sovereign risk premia in the euro area, while so far there has only been a limited increase in term premia. This likely reflects several factors. First, as indicated by the anchoring of longer-term inflation expectations, this inflation episode has been interpreted throughout as a temporary phase, with a sufficient response from central banks to ensure that the initial inflation shocks do not mutate into permanent inflation. In turn, this has meant that longer-term bond yields rose by less than shorter-term interest rates Second, the 2020 launch of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme of joint debt and grants caused a reassessment of country-level risk premia by investors, in view of the solidarity demonstrated by EU Member States in the face of a severe tail risk. Third, the flexible design of the 2020 PEPP and 2022 announcement of the transmission protection instrument (TPI) provided reassurance to investors that unwarranted, disorderly dynamics in sovereign debt markets posing a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy would not be tolerated, provided that countries comply with a set of established “prudent policy” criteria.

Finally, it is important to take into account the external balance sheet of the euro area, in view of its role in the international transmission of domestic and foreign monetary tightening. In line with the impact of the severe decline in the terms of trade on import payments relative to export revenues, Chart 15 shows that the current account surplus of the euro area declined between the middle of 2021 and early 2023, which is also reflected in the decline in the net international investment position during this period, temporarily interrupting the rising trend observed since 2013, in Chart 21. Aside from the terms of trade channel, the global nature of the inflation shock and the similar monetary policy responses across countries meant that the composition of foreign assets and foreign liabilities played only a limited role in determining the international impact of monetary tightening. For instance, debt-related international investment income inflows and outflows increased by similar amounts between 2021 and 2024.

Of course, taking a wider perspective, the global element of the inflation shock and the monetary policy response has shaped the disinflation process and the calibration of monetary policy. All else equal, the tightening moves by foreign central banks limited the required scale of domestic monetary tightening by slowing down global activity, containing globally-determined commodity prices and pushing up the common component in term premia. At the same time, if domestic monetary tightening had been too limited relative to foreign monetary tightening, exchange rate depreciation might have exerted a larger influence on the domestic disinflation process.

Conclusions

At the time of writing (August 2024), my interim assessment of the effectiveness of ECB monetary policy in responding to the 2021-2022 inflation surges is that there has been good progress in delivering the overriding goal of making sure that inflation returns to target in a timely manner. Crucially, this disinflation process has been underpinned by the forceful transmission of monetary policy to the financial system, the level of demand and inflation expectations.

This has required the ECB to appropriately calibrate its monetary policy stance to ensure that demand has been sufficiently dampened and the anchoring of medium-term inflation expectations sufficiently protected, while also containing the economic costs of a restrictive monetary stance. Among other factors, this calibration needed to take into account: the “re-anchoring from below” of medium-term inflation expectations and the associated pricing-out of low-for-long rate scenarios; the multiple channels by which the unjustified Russian invasion of Ukraine directly served to moderate demand; the inflation-disinflation cycles generated by the pandemic and the energy shock; the interactions between monetary policy and sectoral balance sheets; and the global dimensions of the inflation shock and the international policy response.

Of course, this assessment is necessarily interim: the return to target is not yet secure. In particular, the monetary stance will have to remain in restrictive territory for as long as is needed to shepherd the disinflation process towards a timely return to the target. Equally, the return to target needs to be sustainable: a rate path that is too high for too long would deliver chronically below-target inflation over the medium term and would be inefficient in terms of minimising the side effects on output and employment. The data-dependent challenge for monetary policy will be to chart the sustainable and efficient path to the target.

The views expressed in this contribution are my own and should not be interpreted as representing the collective view of the ECB’s Governing Council. In the nature of a panel contribution, I will not try to provide a comprehensive account. For a more extensive discussion, see Lane, P.R. (2024), “The analytics of the monetary policy tightening cycle”, speech at Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2 May.

It is beyond the scope of this contribution to review the origins of the inflation shock (including the relative contributions of cost-push shocks, sectoral demand-supply imbalances and aggregate demand dynamics at both domestic and global levels) and the optimal timing of the monetary policy response. Rather, I focus on the response of ECB monetary policy from December 2021 onwards. See also Lane, P.R. (2024), “The 2021-2022 inflation surges and monetary policy in the euro area”, The ECB Blog, ECB, 11 March (also published as Lane, P.R. (2024), “The 2021-2022 inflation surges and monetary policy in the euro area”, in English, B., Forbes, K. and Ubide, Á. (eds.), Monetary Policy Responses to the Post-Pandemic Inflation, Centre for Economic Policy Research, 13 February, pp. 65-95).

Our policy tightening has also been reflected in sovereign bond markets, which have coped well with the rapid increase in interest rates. It is plausible that the remarkably smooth transmission of the forceful tightening cycle to the sovereign bond market would not have been possible to the same extent without pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) flexibility and the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). The EU-wide solidarity embodied in the Next Generation EU programme has also played a vital role in reducing risk premia.

Given the much shorter average duration of commercial credit in the euro area relative to the United States, the transmission of our policy rate hikes to the lending rates on loans to firms was much more forceful than transmission in the United States, where the average maturity of firm loans is longer and loans are priced off the long-end Treasury curve that has been quick to invert in anticipation of lower inflation and future rate cuts. In other words, the borrowing conditions faced by our companies have evolved in much tighter sync with the ECB's policy intentions.

With some lag, also due to the initial conditions of negative interest rates, time deposit rates – particularly those for firms – have closely followed policy rate hikes. However, the substantial central bank liquidity and low credit demand have reduced the pressure to raise deposit rates. There has been substantial variation in the response of deposit and lending rates across the member countries, driven in part by differences in competition within national banking systems.

This indicator is based on the responses to the euro area bank lending survey. See also Dimou, M., Ferrante, L., Köhler-Ulbrich, P. and Parle, C. (2023), “Happy anniversary, BLS – 20 years of the euro area bank lending survey”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB.

During the phase of policy rate hikes, the weakening in euro area monetary dynamics was primarily driven by the sharp adjustment in bank lending, while in the United States it reflected other sources of money creation (such as bank purchases of securities, external monetary flows and banks’ wholesale funding, as well as quantitative tightening), with bank lending contributing only at a later stage.

One driver of the drop in credit was the significant adjustment seen in the real estate market, exacerbated by an initial condition of exuberance in some residential segments/countries and the structural fall in the demand for some commercial real estate after the pandemic.

Since there were extensive mobility restrictions in late 2021 and early 2022 due to concerns about the Omicron variant, the full pandemic reopening in Europe only took hold around March 2022 (by coincidence at the same time as the Russian invasion of Ukraine). The pandemic reopening was associated with strong demand-supply mismatches in contact-intensive services, as strong demand outpaced initially limited supply. The easing of supply chain bottlenecks and a strong backorder book allowed the manufacturing sector to grow during this period.

In terms of the sectoral impact, monetary policy has had a stronger direct impact on activity levels in interest-sensitive sectors such as construction, capital goods and consumer durables and a slower impact on activity levels in the services sector. Estimates suggest that the peak impact of policy tightening on activity levels is larger for manufacturing than for services, with the peak impact occurring in the fourth quarter of 2023, and larger for business and housing investment than for private consumption, with the transmission to business investment strengthening further in the first quarter of 2024.

Allayioti, A., Górnicka, L., Holton, S. and Martínez Hernandez, C. (2024), “Monetary policy pass-through to consumer prices: evidence from granular price data”, Working Paper Series, ECB, forthcoming.

The accommodative policy stance since 2014 indicates that the Governing Council did not consider 1.7 per cent to be sufficiently close to two per cent to meet the goal of delivering inflation “below, but close to, two per cent”.

This was also facilitated by the explicit commitment to a symmetric two per cent inflation target in the ECB’s monetary policy strategy statement that was published in July 2021.

There was also a marked increase in the proportion of survey respondents that expected inflation to remain above target in the long-term: the evolution of the right-tail of the distribution has been closely monitored throughout the tightening campaign.

The right tail of the distribution of long-term inflation expectations in the SPF has diminished markedly compared with the peak inflation phase in late 2022. The inflation risk premium embedded in five-year-on-five-year inflation swaps has declined by about 40 basis points since last summer. ECB staff have also conducted a model-based exercise on the development of upside de-anchoring risks under the actual interest rate path during the hiking phase, as well as a counterfactual analysis where the rate is assumed to have remained on the path underlying the December 2021 staff projections (Christoffel, K. and Farkas, M. (2024), “Monetary policy and the risks of de-anchoring of inflation expectations”, IMF Working Papers, International Monetary Fund, forthcoming). In the anchored regime, the perceived inflation target is in line with the actual two per cent target. In contrast, in the de-anchored regime, inflation expectations are driven by past and current inflation realisations, even though the central bank continues to pursue the unchanged two per cent target. Due to the tightening of monetary policy, the credibility of the central bank has been maintained by containing upside de-anchoring risks. If rates had been kept at the level of December 2021, the risks would have increased considerably.

Cavallo, A., Lippi, F. and Miyahara, K. (2024), “Large Shocks Travel Fast,” American Economic Review: Insights, forthcoming; L’Huillier, J.-P. and Phelan, G. (2024), “Can Supply Shocks Be Inflationary with a Flat Phillips Curve?”, mimeo, Brandeis University.

Karadi, P., Nakov, A., Nuño, G., Pasten, E. and Thaler, D. (2024), “Strike while the iron is hot: optimal monetary policy with a nonlinear Phillips Curve”, CEPR Discussion Papers, No 19339, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

The notable impact of sectoral shocks on the overall price level via cost channels and relative price rigidities meant that exclusion-type measures (such as core inflation) did not provide a good proxy for properly-measured underlying inflation dynamics. In order to capture the indirect impact of bottlenecks and energy inflation on measures of underlying inflation, ECB staff developed adjusted measures of underlying inflation that “partial out” these indirect influences. See Bańbura, M., Bobeica, E., Bodnár, K., Fagandini, B., Healy, P. and Paredes, J. (2023), “Underlying inflation measures: an analytical guide for the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB; and Bańbura, M., Bobeica, E. and Martínez Hernández, C. (2023), “What drives core inflation? The role of supply shocks”, Working Paper Series, No 2875, ECB. See also Lane, P.R. (2022), “Inflation Diagnostics”, The ECB Blog, 22 November; and Lane, P.R. (2023), “Underlying inflation”, lecture at Trinity College Dublin, 3 March.

Arce, O., Ciccarelli, M., Kornprobst, A. and Montes-Galdón, C. (2024), “What caused the euro area post-pandemic inflation?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 343, ECB. Important other contributions include Guerrieri, V., Marcussen, M., Reichlin, L. and Tenreyro, S. (2023), “The Art and Science of Patience: Relative Prices and Inflation”, Geneva Reports on the World Economy, No 26; Di Giovanni, J., Kalemli-Özcan, Ṣ., Silva, A. and Yildirim, M.A. (2024), “Global supply chain pressures, international trade, and inflation”, mimeo, Brown University; Dao, M., Gourinchas, P.-O., Leigh, D. and Mistra, P. (2024), “Understanding the International Rise and Fall of Inflation Since 2020”, Journal of Monetary Economics, in press; Forbes, K., Ha, J. and Kose, M.A. (2024), “Demand versus supply: drivers of the post-pandemic inflation and interest rates”, VOXEU, 9 August.

The array of fiscal subsidies that were introduced in late 2022 to contain the peak impact of the energy shock on households have been an additional factor in shaping the intensity and duration of the disinflation process in the euro area. Many of these temporary measures are expiring in the course of 2024, which is putting temporary upward pressure on the price level. This process will continue to play out during 2025.

On the role of bank balance sheets, see: Altavilla, C., Canova, F. and Ciccarelli, M. (2020), “Mending the broken link: heterogeneous bank lending rates and monetary policy pass-through”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 110, pp. 81-98; Bernanke, B. and Gertler, M. (1990), “Financial Fragility and Economic Performance”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, No 1, pp. 87-114; Bernanke, B. and Blinder A. (1988), “Credit, Money, and Aggregate Demand”, American Economic Review, Vol. 78, No 2, pp. 435-439; Jiménez, G. et al. (2012), “Hazardous Times for monetary policy: what do twenty-three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit-risk taking?”, Econometrica, Vol. 82, No 2, pp. 463-505; Kashyap, A. and Stein, J. (1995), “The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 42, pp. 151-195; Kashyap, A. and Stein, J. (2000), “What Do a Million Observations on Banks Say about the Transmission of Monetary Policy?”, American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No 3, pp. 407-428; Kishan, R. and Opiela, T. (2000), “Bank Size, Bank Capital, and the Bank Lending Channel”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 32, No 1, pp. 121-141; Peek, J. and Rosengren, E. (1995), “Bank regulation and the credit crunch”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 19, No 3-4, pp. 679-692; Stein, J. (1998), “An Adverse-Selection Model of Bank Asset and Liability Management with Implications for the Transmission of Monetary Policy”, The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 29, No 3, pp. 466-486; Van den Heuvel, S. (2002), “Does bank capital matter for monetary transmission?”, Economic Policy Review, Vol. 8, No 1, pp. 259-265.On the role of household balance sheets, see: Auclert, A. (2019), “Monetary Policy and the Redistribution Channel”, American Economic Review, Vol. 109, No 6, pp. 2333-2367; Carroll, C., Slacalek, J., Tokuoka, K. and White, M.N. (2017), “The distribution of wealth and the marginal propensity to consume”, Quantitative Economics, Vol. 8, No 3, pp. 977-1020; Crawley, E. and Kuchler, A. (2023), “Consumption Heterogeneity: Micro Drivers and Macro Implications”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 15, No 1, pp. 314-341; Jappelli, T. and Pistaferri, L. (2010), “The Consumption Response to Income Changes”, Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 2, pp. 479-506; Slacalek, J., Tristani, O. and Violante, G.L. (2020), “Household balance sheet channels of monetary policy: a back of the envelope calculation for the euro area”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 115, No 103879.On the role of firm balance sheets, see: Altavilla, C., Burlon, L., Giannetti, M. and Holton, S. (2022), “Is there a zero lower bound? The effects of negative policy rates on banks and firms”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 144, No 3, pp. 885-907; Altavilla, C., Gürkaynak, R.S. and Quaedvlieg, R. (2024), “Macro and micro of external finance premium and monetary policy transmission”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming; Cloyne, J., Ferreira, C., Froemel, M. and Surico, P. (2023), “Monetary Policy, Corporate Finance, and Investment”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 21, No 6, pp. 2586-2634; Caglio, C.R., Darst, R.M. and Kalemli-Özcan, Ṣ. (2021), “Collateral Heterogeneity and Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from Loans to SMEs and Large Firms”, NBER Working Papers, No 28685, National Bureau of Economic Research; Ippolito, F., Ozdagli, A.K. and Perez-Orive, A. (2018), “The transmission of monetary policy through bank lending: the floating rate channel”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 95, pp. 49-71; Jeenas, P. and Lagos, R. (2024), “Q-Monetary Transmission”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 132, No 3; Ottonello, P. and Winberry, T. (2020), “Financial Heterogeneity and the Investment Channel of Monetary Policy”, Econometrica, Vol. 88, No 6, pp. 2473-2502.

There were significant differences across the member countries. See also Pallotti, F., Paz-Pardo, G., Slacalek, J., Tristani, O. and Violante, G.L. (2023), “Who bears the costs of inflation? Euro area households and the 2021–2022 shock,” Working Paper Series, No 2877, ECB.

For example, in May 2022, credit to the general government constituted approximately 7 per cent of total bank assets.

In terms of bank lending, higher interest payments on central bank reserves exert both income and substitution effects. While the former might boost bank lending by relaxing capital constraints via higher profitability, the latter effect seems to dominate: bank lending in the euro area fell sharply, in part due to the reduced incentive for banks to lend when simply holding central bank reserves offers an increased payoff.

Akinci, O., Benigno, G., Del Negro, G., Queralto, A. (2023), “The Financial (In)Stability Real Interest Rate, r**”, Staff Report, No 946, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, demonstrate via model simulations that more resilient banking sectors (proxied by higher asset quality and equity ratios) can withstand larger policy rate increases without triggering financial instability events. The transmission of monetary policy tightening is generally stronger for poorly capitalised banks (see for example Peek, J. and Rosengren, E. (1995) “Bank regulation and the credit crunch”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 19; Kishan, R. and Opiela, T. (2000) “Bank Size, Bank Capital, and the Bank Lending Channel.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 32; Van den Heuvel, S. (2002) “Does bank capital matter for monetary transmission?” Economic Policy Review, Vol. 8; Jiménez G. et al (2012) “Hazardous times for monetary policy: What do twenty-three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit-risk taking?” Econometrica; Altavilla, C., Canova, F. and Ciccarelli, M. (2020) “Mending the broken link: Heterogeneous bank lending rates and monetary policy pass-through.” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 110) and illiquid banks (Stein, J. (1998) “An Adverse-Selection Model of Bank Asset and Liability Management with Implications for the Transmission of Monetary Policy”, The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 29; Kashyap, A. and Stein, J. (2000) “What Do a Million Observations on Banks Say about the Transmission of Monetary Policy?”, American Economic Review, Vol. 90; Bernanke, B. and Gertler, M. (1990) “Financial Fragility and Economic Performance”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, Bernanke, B. and Blinder A. (1988) “Credit, Money and Aggregate Demand”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 78). In this regard, the ample central bank reserves play an important role in maintaining high bank liquidity buffers with lower sovereign-bank nexus, and contribute to decrease the financial vulnerability of the banking system to interest rate hikes (Greenwood, R., Hansen, S. and Stein, J. (2016), “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet as a Financial Stability Tool”, Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; Altavilla, C., Rostagno, M., Schumacher, J. (2023), “Anchoring QT: Liquidity, credit and monetary policy implementation”, Discussion Paper, No 18581, CEPR).

Whereas the decline in total Eurosystem assets since summer 2022 amounts to around €2.4 trillion, the decline in excess reserves is noticeably smaller than the sum of the decline in monetary policy assets due to partially offsetting changes in autonomous factors, notably the decline in government deposits held with the Eurosystem.

See Altavilla, C., Rostagno, M. and Schumacher, J., op. cit. See also Acharya, V. and Rajan, R. (2022), “Liquidity, liquidity everywhere, not a drop to use – Why flooding banks with central bank reserves may not expand liquidity”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 29680, National Bureau of Economic Research; Acharya, V., Chauhan, R., Rajan, R. and Steffen, S. (2023), “Liquidity dependence and the waxing and waning of central bank balance sheets”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 31050, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Of course, the counterpart to the high stock of central bank reserves at the start of the tightening cycle was the high stock of assets held by the central bank. For the ECB, the bond holdings associated with monetary policy peaked at €4.96 billion in June 2022, while the long-term refinancing loans to the banking system peaked at €2.22 billion in June 2021. The gap between the low yields on the purchased bonds and the high interest rate paid out on central bank reserves resulted in negative net income for the Eurosystem. Initially, there were also negative net income flows from the TLTRO programme, since the interest rate received on these loans had been set during the pandemic at a rate of DFR - 50 basis points for banks fulfilling the lending benchmarks. However, this interest rate was adjusted to equal the DFR by November 2022, such that the negative income flows from this programme were limited. Until the recalibration of its conditions that became effective on 23 November 2022, there were also negative net income flows from the TLTRO programme due to the pricing incentives put in place earlier on to support lending to the economy during the pandemic period. The decision to recalibrate TLTRO-III to align with the broader monetary policy normalisation process was made on 27 October 2022. It was determined that, starting from 23 November 2022, the interest rate on all remaining TLTRO-III operations would be indexed to the average of the applicable key ECB interest rates from that date onward.

In relation to asset purchase programmes, the extent of the net fiscal impact depends on whether the maturity structure of government debt would have been different in the absence of a quantitative easing programme. More generally, an accurate assessment would also have taken into account the extent to which the level of GDP and thereby the overall level of tax revenue would have been different in the absence of a quantitative easing programme. See, for example, Del Negro, M. and Sims, C. A. (2015), “When Does a Central Bank’s Balance Sheet Require Fiscal Support?” Journal of Monetary Economics, No 73, pp.1-19; Reis, R. (2015), “Different Types of Central Bank Insolvency and the Central Role of Seignorage”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 21226; Belhocine, N., Bhatia, A. V. and Frie, J. (2023) “Raising Rates with a Large Balance Sheet: The Eurosystem’s Net Income and its Fiscal Implications”, IMF Working Paper Series, No 2023/145, Garcia-Escudero, E.E. and Romo Gonzalez, L.A. (2024), “Why a central bank’s bottom line doesn’t matter (that much)”, Economic Bulletin, Banco de España, 2024Q2 and Gebauer, S., Pool, S. and Schumacher, J. (2024), “The Inflationary Consequences of Prioritising Central Bank Profits”, ECB, mimeo.

Den Europæiske Centralbank

Generaldirektoratet Kommunikation

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Eftertryk tilladt med kildeangivelse.

Pressekontakt