Improving the functioning of Economic and Monetary Union: lessons and challenges for economic policies

Speech by Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the NABE Symposium, 16 April 2018

Slides from the presentationThe ongoing economic expansion shows that our monetary policy has been effective in laying the groundwork for a return of inflation to a rate below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. [1]

Euro area real GDP has expanded for 19 consecutive quarters. The latest economic data and survey results point towards some moderation of late, following several quarters of very strong growth Inflation developments, however, remain subdued, and we have not yet met the Governing Council’s three criteria – convergence, confidence and resilience – for a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation, which is our stated condition for ceasing our net asset purchases. Overall, an ample degree of monetary stimulus remains necessary for underlying inflation pressures to continue to build up and support headline inflation developments over the medium term. Hence, we must be patient, persistent and prudent with our policy.

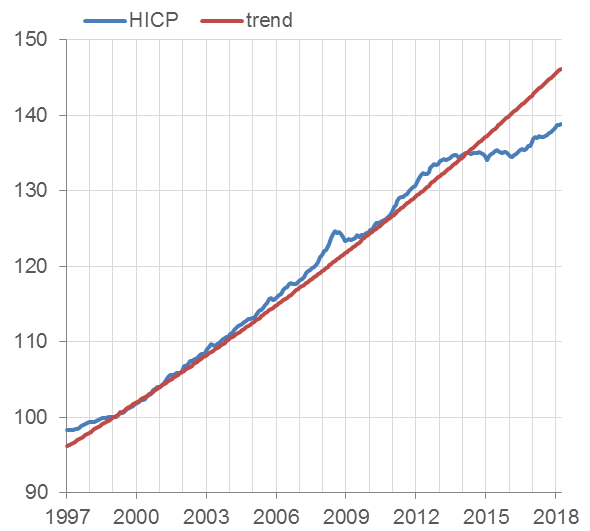

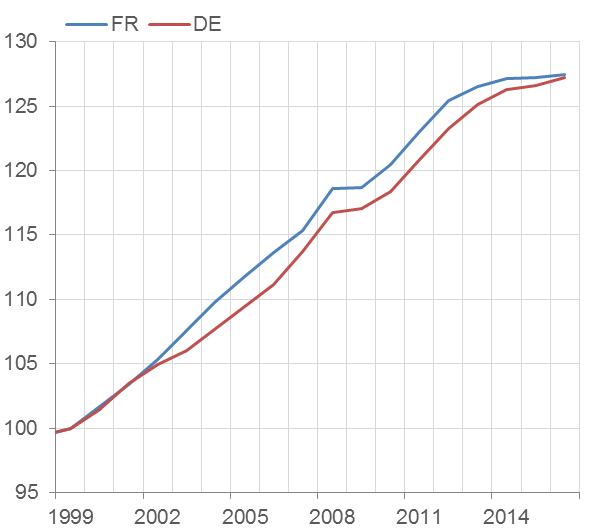

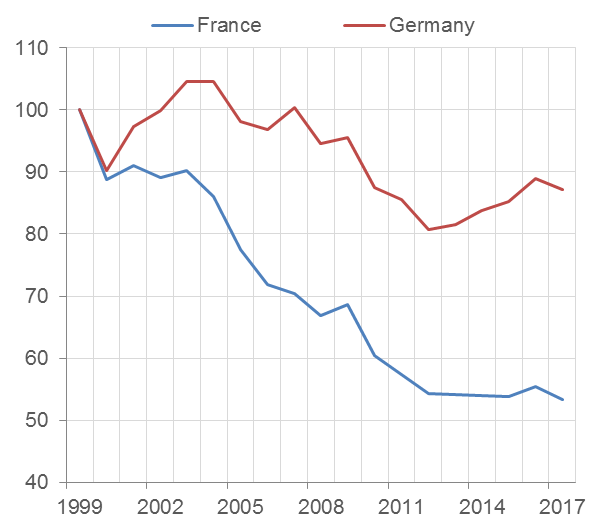

Figure 1: Price level

(1999m1=100, trend= year-on-year HICP inflation at 2%)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Latest observations: March 2018 (monthly data).

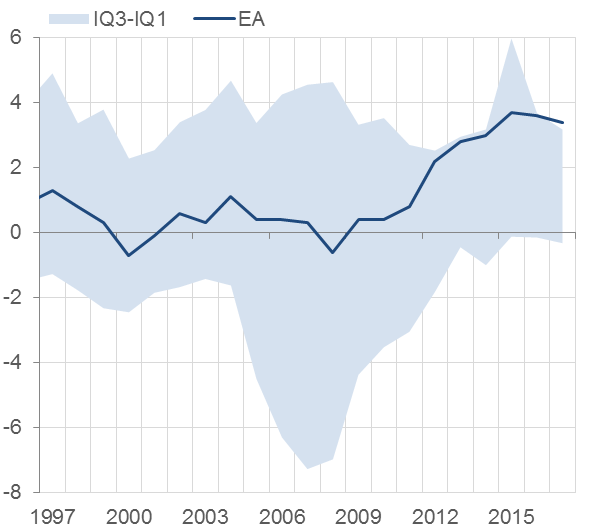

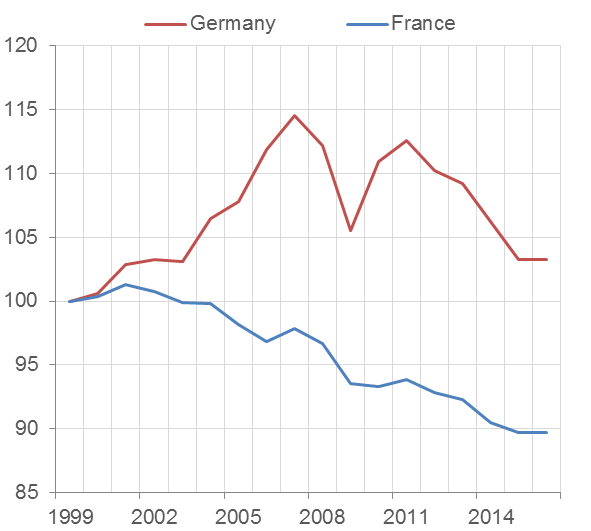

Figure 2: Current account

(as % of GDP)

Sources: OECD and ECB calculations.

Latest observations: 2017 (annual data).

Our monetary policy has effectively contributed to euro area macroeconomic adjustment through the staunch pursuit of our price stability mandate. Monetary policy, however, is only one side of the story. Price stability is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for sustained and balanced growth in Europe. The run-up to the crisis proved that macroeconomic imbalances can grow amid price stability (see Figure 1 and 2), highlighting the need to keep economic policy high on Europe’s agenda.

Tonight I would like to concentrate on economic policies and their essential role in ensuring a smooth functioning of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). I will look back at the experience of the euro area since 1999 and illustrate the emergence of macroeconomic imbalances by focusing on three countries: Spain, Germany and France.

The crisis acted as a litmus test for Europe’s institutional framework, revealing the need for a number of institutional reforms. Lessons have been learned and significant progress towards strengthening EMU has been achieved, including elevating the responsibility of banking supervision from national to the European level, the creation of the European Stability Mechanism as a permanent crisis management institution, and improvements in the EU surveillance framework for economic policies.[2] Progress towards completing the banking union and the capital markets union has rightly emerged as one of the immediate priorities in strengthening EMU,[3] not least as such progress is seen as crucial in supporting macroeconomic adjustment in a monetary union.

Today it is fair to say that the euro area has lived up to the challenges posed by the existential crisis and euro area countries have displayed a strong commitment to EMU. Macroeconomic adjustment in EMU has made significant progress, with countries implementing significant growth-enhancing reforms and correcting external imbalances, but this process has been difficult. Countries most affected by the crisis were confronted with significant hardship, even though financial support provided by the Union and its Member States to countries facing acute financing difficulties prevented catastrophic outcomes and cushioned some of its impact by providing time for economic adjustment. Looking forward, in order to sustain a high level of social welfare in the long term, it is essential for euro area countries to improve their capacity to prevent crisis and hence to ensure that macroeconomic adjustment progresses in a smoother way.

The emergence of macroeconomic imbalances

The crisis has demonstrated how persistent losses in competitiveness can translate into macroeconomic imbalances, eventually leading to a painful adjustment. Spain’s experience during the crisis is instructive in this regard.

With the start of Monetary Union, the disappearance of exchange rate risk premia and the unprecedented fall in interest rates facilitated capital inflows and encouraged risk-taking behaviour, resulting in a rapid rise in private debt and a property boom. The expectation of higher levels of income led to excessive consumption and investment relative to the supply capacity of the Spanish economy. This continuous demand pressure generated a positive inflation differential vis-à-vis the rest of the euro area, leading to a strong appreciation of the real exchange rate and an erosion of price competitiveness.[4]

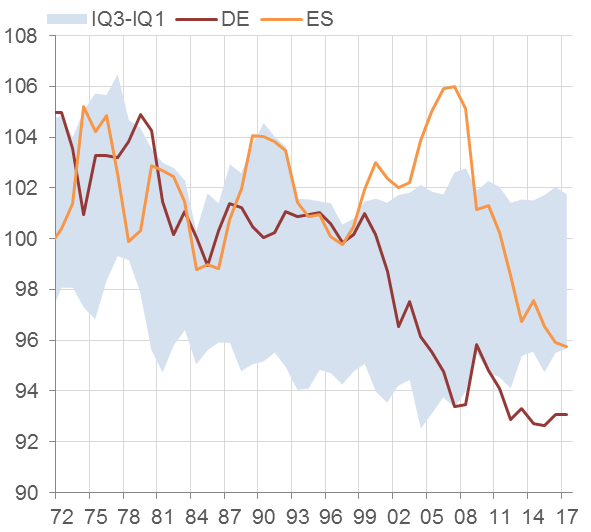

When the crisis hit, the subsequent adjustment was severe – with unemployment rising above 25 percent, a rapid erosion of the fiscal position and a number of bank failures – leading to a significant contraction in both domestic demand (see Figure 3) and real GDP. The same was true for other current account deficit countries, such as Portugal, Ireland and Greece.

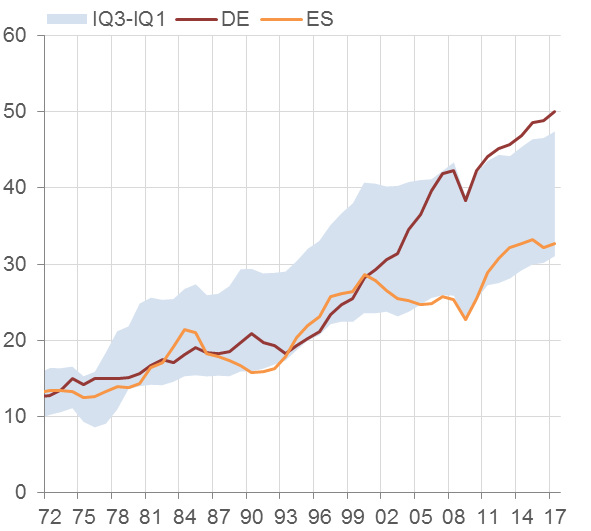

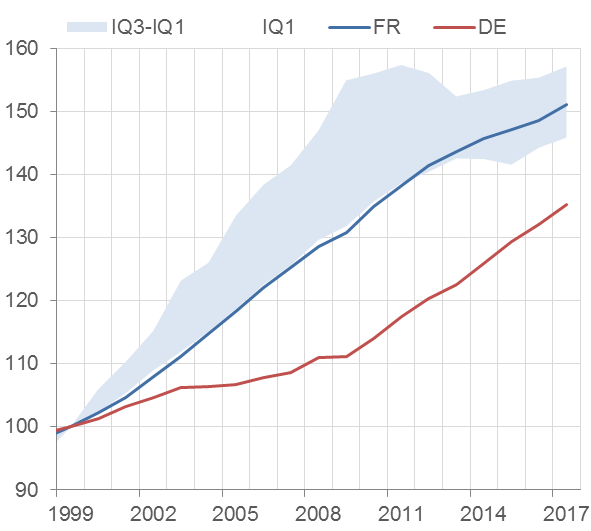

For countries with large current account deficits, the adjustment was painful. The correction of euro area macroeconomic imbalances was particularly asymmetric, with the bulk of the adjustment falling on current account deficit countries through a strong contraction in domestic demand, with limited support from a higher demand contribution from current account surplus countries, despite those countries being less affected by the crisis. Growth in the surplus countries, including Germany, became even more export-oriented (see Figure 4).

An important lesson from the crisis was that the euro area had insufficient tools at its disposal to, on the one hand, prevent the build-up of unsustainable asset price booms and, on the other hand, mitigate their impact if they do occur. The answer to such problems lies, ex ante, in better macroprudential and microprudential policies and better regulation of the financial system and, ex post, in better resolution institutions. Strengthening Europe’s financial framework, including the establishment of the banking union, is the right way to address this source of macroeconomic imbalances. It is of the utmost importance to complete the banking union without delay.

Figure 3: Domestic demand

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Global Financial database, Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The IQ3-IQ1 shows the 25-75% interquartile range of the following countries: AT, DE, BE, FR, IT, ES, PT, EL, NL, FI, US, UK, SE, JP, CA, AU, DK, NO, CH.

Latest observation: 2017.

Figure 4: Exports

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Global Financial database, Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The IQ3-IQ1 shows the 25-75% interquartile range of the following countries: AT, DE, BE, FR, IT, ES, PT, EL, NL, FI, US, UK, SE, JP, CA, AU, DK, NO, CH.

Latest observation: 2017.

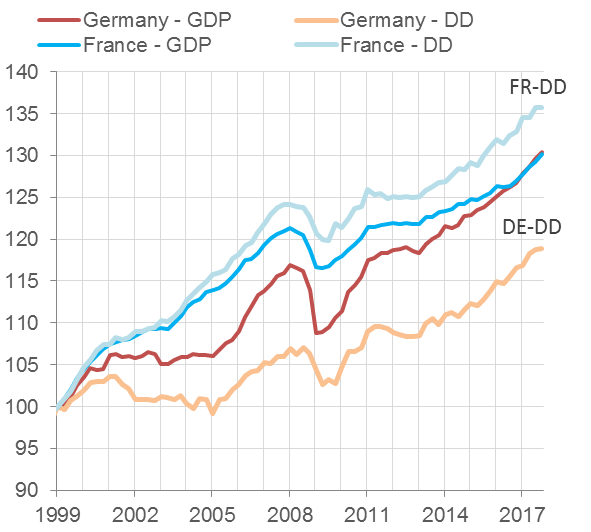

Competitiveness problems in the euro area can also be attributed to factors other than the financial cycle, such as the lack of adequate wage and price flexibility or impediments to factor mobility. The importance of such economic factors already featured prominently in the theory of optimal currency areas, as pioneered by Mundell in 1961. Competitiveness imbalances are one of the most visible symptoms of insufficient macroeconomic adjustment mechanisms in the euro area.[5] The developments in Germany and France – two countries which together represent nearly half of euro area GDP, and have seen broadly similar movements in GDP and in prices (see Figures 5 and 6) since the start of Monetary Union – are instructive in this regard.

Figure 5: Price level

(1999=100)

Sources: AMECO and ECB calculations.

Latest observations: 2017 (annual data).

Figure 6: Domestic demand and GDP

(1999Q1=100)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: DD stands for domestic demand.

Latest observations: 2017Q4 (quarterly data).

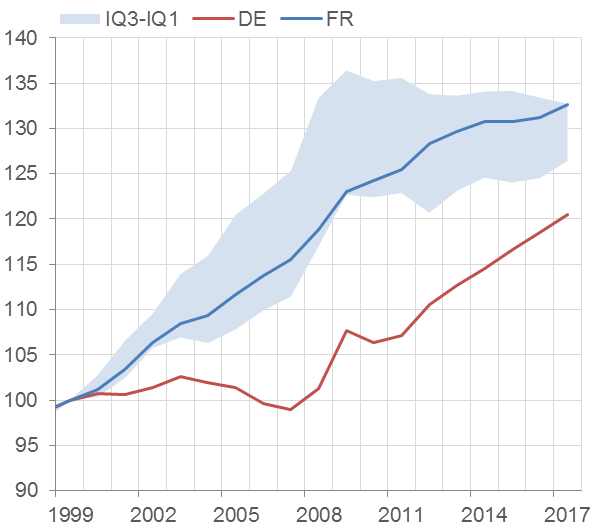

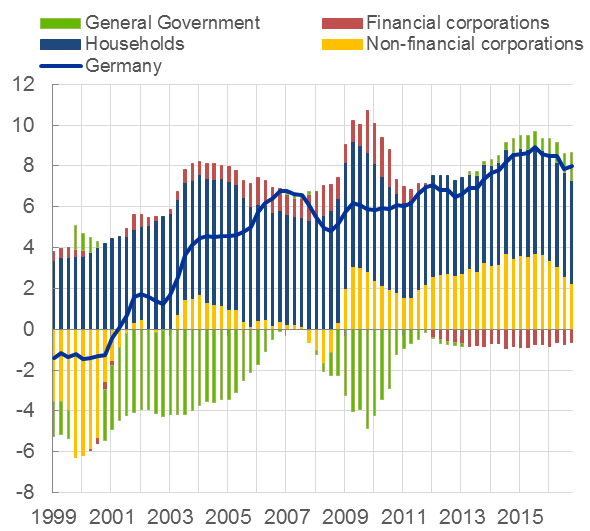

Germany, at the start of Monetary Union, was considered the “sick man of Europe”. At the time, the country was still recovering from the high costs associated with its reunification and its conversion rate was widely considered to be overvalued.[6] The national policy response was a prolonged period of union-backed wage moderation[7] together with a significant labour market overhaul which aimed, among other things, at improving job search efficiency and employment flexibility.[8] The result was striking: from 1999 to 2008, nominal unit labour costs were virtually unchanged for the economy as a whole (see Chart 8) and were thus growing significantly below what the “golden wage rule” would suggest.[9] This resulted in a strong export performance, but weak domestic demand. The economic policies Germany pursued before the crisis largely explain why it emerged relatively unscathed from the Great Recession. Exports recovered swiftly and currently stand at an all-time high, roughly equalling half of the country’s GDP. Exports recovered particularly strongly towards non euro area countries. As a result, the decline in the euro area share in total German exports accelerated. Meanwhile, the domestic demand contribution to GDP continued on its downward path, in part on account of subdued wage growth together with a tight fiscal policy (see Figure 12).

Figure 7: Compensation per employee

(1999=100)

Sources: Ameco and ECB calculations.

Note: The grey shaded area shows the 25-75% range among

EA12 countries.

Latest observation: 2017 (annual data).

Figure 8: Unit Labour Costs

(1999=100)

Sources: Ameco and ECB calculations.

Note: The grey shaded area shows the 25-75% range among

EA12 countries.

Latest observation: 2017 (annual data).

Figure 9: World export market share

(Goods, 1999=100)

Sources: IMF DOTS and ECB calculations.

Note: world export market share calculated as the share of a country’s exports in world exports.

Last observation: 2017 (annual data).

Figure 10: Traded sector mark up

(1999=100)

Sources: AMECO and ECB calculations.

Notes: Mark-up calculated as the difference between sector selling price minus the sectoral unit labour cost developments.

Last observation: 2016 (annual data).

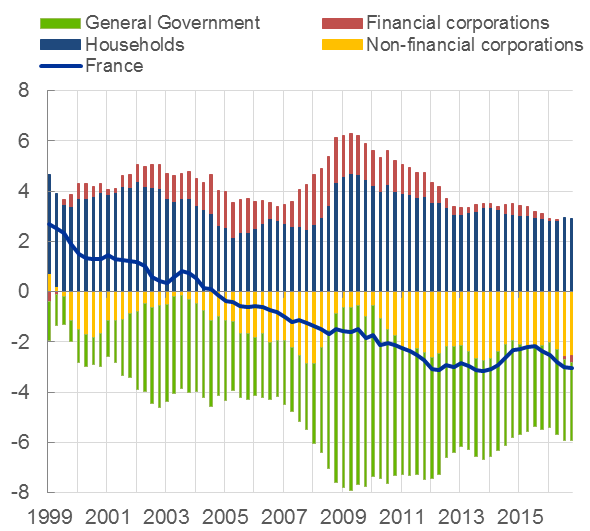

In contrast to Germany, France entered Monetary Union in much better shape. Growth in the initial years was strong and unemployment declined by more than a fourth within five years.[10] Wage increases remained moderate, even below euro area averages (see Chart 7), and unit labour costs moved according to the “golden wage rule”, i.e. at an average annual rate below, but close to, 2%. However, with German unit labour costs remaining virtually unchanged over the period, a significant competitiveness gap built up. This was further aggravated by the crisis, during which French wages remained relatively sticky, in spite of the sharp fall in productivity.[11] The consequences were especially detrimental for the French export sector, which suffered significant losses in market share (see Figure 9), despite the substantial squeeze in profit margins (see Figure 10). At the same time, the contribution of domestic demand to growth became increasingly important, supported by fiscal policy (see Figure 11) and sticky wage developments.

Figure 11: France: net lending/borrowing

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: Data refers to four quarter sums.

Latest observation: 2017Q3.

Figure 12: Germany: net lending/borrowing

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: Data refers to four quarter sums.

Latest observation: 2017Q3.

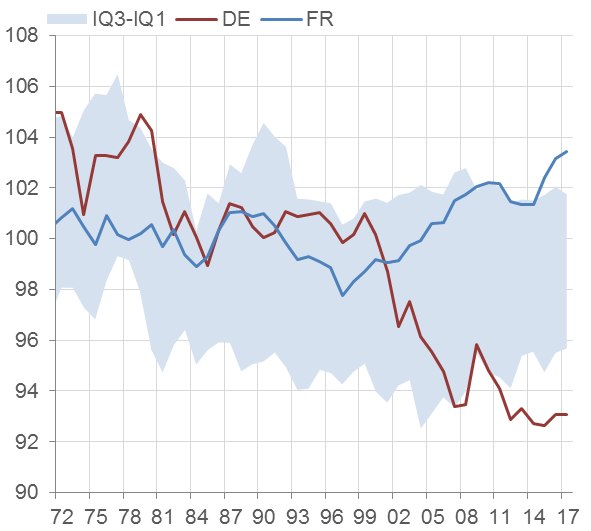

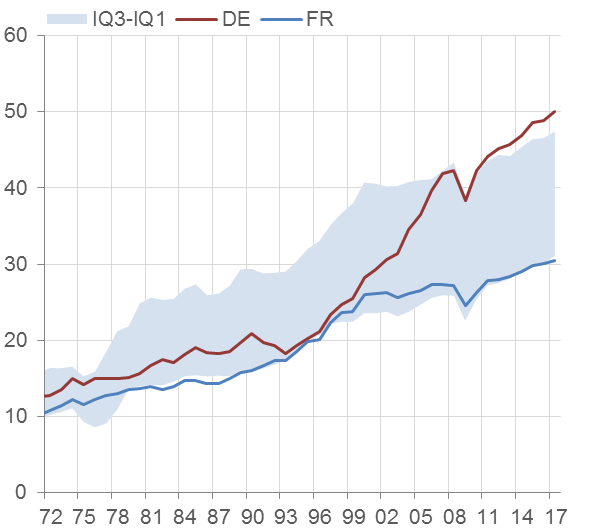

As a result, there is now a striking divergence between France and Germany on a number of macroeconomic dimensions: in Germany, the domestic demand to GDP ratio is now among the lowest across advanced economies, whereas in France, it is among the highest. The opposite is true for exports (see Charts 13 and 14).

Figure 13: Domestic demand

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Global Financial database, Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The IQ3-IQ1 shows the 25-75% interquartile range of the following countries: AT, DE, BE, FR, IT, ES, PT, EL, NL, FI, US, UK, SE, JP, CA, AU, DK, NO, CH. Latest observation: 2017.

Figure 14: Exports

(as % of GDP)

Sources: Global Financial database, Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The IQ3-IQ1 shows the 25-75% interquartile range of the following countries: AT, DE, BE, FR, IT, ES, PT, EL, NL, FI, US, UK, SE, JP, CA, AU, DK, NO, CH. Latest observation: 2017.

The recent economic policy orientations and plans set out by the German and French authorities are steps in the right direction. In particular, the labour market reforms that have already been implemented by the French authorities, and those that are still planned, could yield sizeable growth benefits and improve competitiveness. These recent developments show that cross-country interdependencies in the Monetary Union are better internalised in national decision-making processes.

Some lessons for the future

Our monetary policy measures are bearing fruit, and the growth outlook confirms our confidence that inflation will converge towards our aim of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. Monetary policy alone cannot prevent divergences in a monetary union. Sound economic policies are the key drivers of Europe’s prosperity. They are pivotal to the smooth functioning of EMU, thereby preventing the emergence of macroeconomic imbalances.

The nature of EMU makes macroeconomic adjustment in the euro area more complex than in a federal state. Monetary policy is a competence assigned at EU level. The European Central Bank’s price stability objective is enshrined in the Treaty.[12] By contrast, economic policy remains in the remit of Member States.[13] It is, however, a Treaty obligation for Member States to regard their economic policies as a matter of common concern and to coordinate them.

Our framework for the coordination of economic policies was clearly not effective in preventing the emergence of lasting imbalances in the euro area in the run-up to the crisis. Protracted losses of competitiveness eventually led to unsustainable external positions and even “sudden stops” in the financing of external deficits. This is not new. Unfortunately, we can point to several episodes in history when governments and social partners failed to internalise external constraints, resulting in widening imbalances. This typically led to currency crises and exchange rate realignments in Europe. Monetary instability prevented Europeans from reaping the full benefit of the internal market and limited Europe’s growth potential and emergence as a global economic actor.

In our institutional framework for economic policies, it is primarily up to the Member States to respond to the economic challenges they are faced with, thereby ensuring that their economic structures are compatible with participation in Monetary Union. To reap the full benefit of Monetary Union, it is essential to ensure that national economic policies lead to sustainable growth. Preventing the emergence of economic imbalances and creating the conditions for a thriving social market economy is not only a matter of national interest. It is also a matter of common concern, as a crisis in one country has repercussions for all members of Monetary Union. Effective surveillance is needed at both EU and national level.

Looking ahead, we need to further enhance the coordination of national economic policies. National economic policies, the effects of which can propagate through the EU, should no longer be decided in isolation. At the European level, the European Semester process for the coordination of economic policies – including the macroeconomic imbalance procedure – which was introduced by the EU in 2011, can play a key role.[14] However, it should be used to its full potential. Equally important, though, is for national debates and decision-making processes to more fully internalise what it means to be part of Monetary Union. Precisely for this purpose, the Five Presidents’ Report of 12 February 2015[15] called for the set-up of National Competitiveness Authorities.[16] These bodies are intended to foster national responsibility for identifying any necessary reforms and facilitating their implementation. Subsequently, the Council of the European Union adopted on 19 September 2016 a Recommendation for the establishment of National Productivity Boards[17] and Member States were invited to implement the Recommendation by 20 March 2018. We should make full use of this Recommendation. National Productivity Boards have the potential to become an important catalyst in supporting the sound functioning of national adjustment mechanisms.

[1] I would like to thank Isabel Vansteenkiste for her support in preparing this speech.

[2] The “two-pack” and “six-pack” legislative packages, which bundle together 6 regulations and 1 directive, aim to more closely coordinate economic policies through (i) a strengthening of budgetary surveillance under the Stability and Growth Pact, (ii) the introduction of a new procedure in the area of macroeconomic imbalances, (iii) the establishment of a framework for dealing with countries experiencing difficulties with financial stability and (iv) the codification in legislation of integrated economic and budgetary surveillance in the form of the European Semester (see, for instance, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014DC0905 ).

[3] See, for instance, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/news/reducing-risk-banking-union-2018-mar-14_en

[4] See A. Estrada, J.F. Jimeno and J.L. Malo de Molina (2009), The Spanish economy in EMU: the first ten years, Banco de España, Documentos Ocasionales, No. 0901

[5] See A. Sapir (2016), The Eurozone needs less heterogeneity, VoxEU, 12 February 2016

[6] See F. Schrapf (2018), International Monetary Regimes and the German Model, Max Planck Institute for the study of societies, Discussion paper 18/1.

[7] See P. Bofinger (2015), German wage moderation and the EZ crisis, VoxEU

[8] See N. Engbom, E. Detragiache, and F. Raei (2015), The German Labour Market Reforms and Post-Unemployment Earnings, IMF Working paper 15/162.

[9] The golden wage rule states that real wages should grow in line with (medium-run) national productivity and nominal wages so as to be compatible with price stability. This implies that nominal wages in each country should equal (medium-run) national productivity plus the target inflation rate of the central bank (see, for instance, European Commission, 2005). In practice, this would mean that on average, unit labour costs growth should approximately equal the target inflation rate of the central bank.

[10] See, for instance, J. Pisani-Ferry (2003), The surprising French employment performance: what lessons? CESifo Working paper number 1078

[11] See for instance S. Collignon and P. Esposito (2017), Labour costs and returns on capital in the EMU: a new measure of competitiveness. Mimeo

[12] Article 127 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

[13] Articles 120 and 121 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

[14] To reinforce ex ante coordination of EU Member States’ economic and fiscal policies, a new monitoring cycle was introduced in 2011: the “European semester” – a six-month period every year during which national budgetary and structural policies will be reviewed to detect any inconsistences and emerging imbalances while major budgetary decisions are still under preparation. Specifically, the reform reinforces the preventive arm of the Stability and Growth Pact, introduces a new procedure for addressing macroeconomic imbalances, and places greater emphasis on monitoring the national fiscal frameworks, identifying macrostructural growth bottlenecks and detecting macrofinancial risks in the Member States (see W. Köhler-Töglhofer and P. Part (2011), Macro Coordination under the European Semester. Monetary Policy and the Economy December 2011 issue).

- [15] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/5-presidents-report_en.pdf

[16] See https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/InformesBoletinesRevistas/BoletinEconomico/descargar/16/nov/files/be1611-art2e.pdf

[17] Council Recommendation of 20 September 2016 on the establishment of National Productivity Boards (2016/C 349/01). Euro area member states are expected to implement the recommendation within 18 months from its approval on 19 September 2016.

Europos Centrinis Bankas

Komunikacijos generalinis direktoratas

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurtas prie Maino, Vokietija

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Leidžiama perspausdinti, jei nurodomas šaltinis.

Kontaktai žiniasklaidai