The ECB’s recent monetary policy measures: Effectiveness and challenges

Camdessus lecture by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, IMF, Washington, DC, 14 May 2015

Ladies and gentlemen,

Over the past year the ECB has taken a series of major monetary policy measures, culminating in our decision in January this year to expand our asset purchases towards public sector securities. While the aim of these measures is the same as it has always been – maintaining price stability over the medium-term – their form is unprecedented for our central bank. And as such our policy decisions have become more complex in two key ways.

First, as interest rates have reached their effective lower bound in the euro area, we have become more constrained in our ability to deploy conventional monetary policy tools. This has required us to develop new instruments to achieve the same results.

Second, because the use of these new instruments can have different consequences than conventional monetary policy, in particular with respect to the distribution of wealth and the allocation of resources, it has become more important that those consequences are identified, weighed and where necessary mitigated.

In my remarks today I would like to discuss how our monetary policy has evolved within this new environment – both in terms of how we have deployed our instruments and how we are managing their consequences.

1. Monetary policy in an uncertain environment

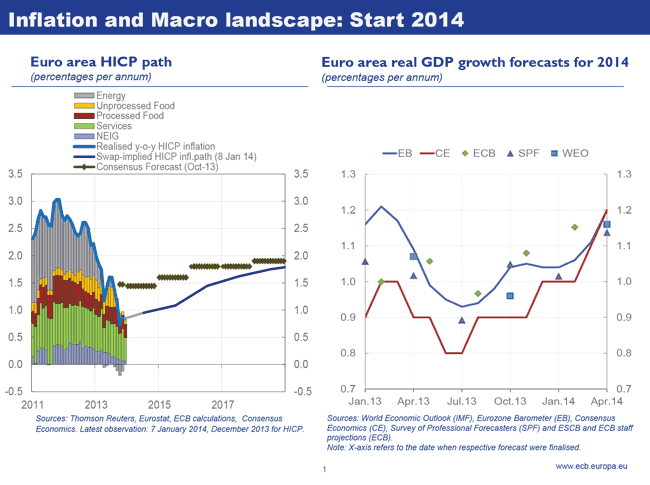

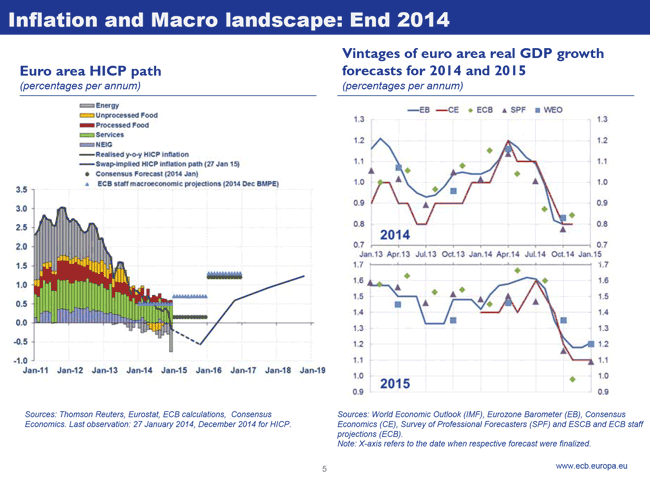

At the start of 2014, the macroeconomic landscape in the euro area was characterised by a high degree of uncertainty.

On the one hand, we were confronted with a consistent and broad-based downward trend in past inflation, falling from 3% at the end of 2011 to less than 1% at the beginning of 2014. But on the other, sentiment on the economic outlook was relatively upbeat for 2014, with nearly all forecasters expecting the recovery to firm over the course of the year. In this context, while we felt relatively comfortable that the medium-term inflation outlook was secure, the risks surrounding that outlook were clearly elevated. It hinged crucially on the benign macroeconomic scenario materialising and no further shocks emerging (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Macro and inflation landscape in early 2014

Given that uncertainty and its impact on expectations of future monetary policy, it became much more important for us to communicate clearly how we would respond should different risks to the outlook emerge. In this context, in a speech in Amsterdam in April I laid out our reaction function to what we saw as the three most likely contingencies. [1]

These were, first, an unwarranted tightening of the policy stance emanating from external developments, which would warrant a more conventional response. Second, a persistent impairment of the bank lending channel to which we would react with targeted credit easing measures – that is, measures to provide longer-term refinancing for banks and free up capacity for new lending on their balance sheets. And third, a worsening of the medium-term outlook for inflation and/or a loosening in the anchoring of inflation expectations, which would justify overcoming the lower bound constraint on interest rates by engaging in a broad-based asset purchase programme.

Through 2014 each of these contingencies materialised.

As the discussion of exit from accommodative monetary policy in the US gathered pace it became increasingly important for us to distinguish the diverging paths of monetary policy on either side of the Atlantic. From June onwards we therefore entered the first contingency and brought our main refinancing rate to its effective lower bound, while also introducing measures to strengthen the propagation of short-term rates to the medium-term curve. This included strengthening our forward guidance and introducing a negative interest rate on our deposit facility, which combined to measurably increase the traction of our policy rates over the shape of the yield curve.

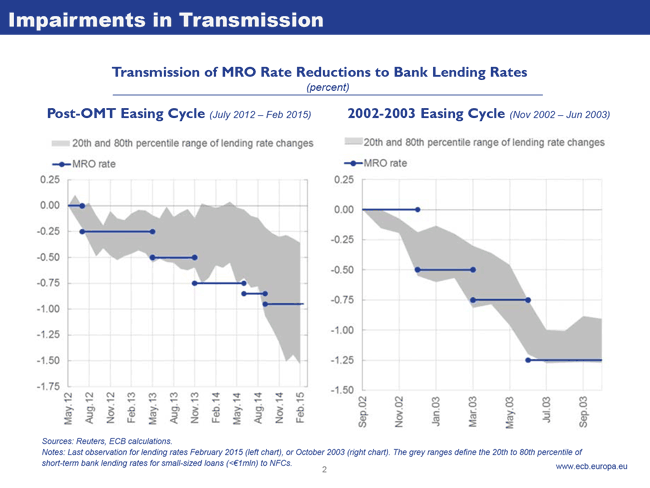

But crucially, by the middle of the year we were still not seeing movements in the yield curve being reflected in the actual borrowing conditions faced by firms and households across the euro area, which meant this considerable easing was not having the impact we would normally expect (Chart 2). It was in this context that we moved into the second contingency and launched our credit easing measures. This took the form of targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), which provide cheap long-term funding to banks on the condition that they expand loans to the real economy, and thereby help restore a more normal supply and pricing of credit.

Chart 2: Impairments in transmission

When we introduced these measures there were some doubts among outside observers as to how powerful a boost to credit supply could be, given uncertainty over the health of the euro area banking sector and signs that credit demand was also weak. It was therefore crucial that at this time the Comprehensive Assessment was also reaching its conclusion, which had encouraged banks to frontload their deleveraging and strengthen their balance sheets – by over €200 billion in advance of the outcome. This put the sector in a stronger position to transmit this new monetary impulse.

Moreover, in our view there was a large degree of endogeneity in credit developments: banks were attaching higher margins to new loans to reflect their elevated risk perceptions; those higher interest rates were then taxing borrowers with outstanding credit and limiting the demand for new credit; this was in turn weighing on the economic recovery and contributing to higher loan delinquencies for banks; and then banks were justified in charging those higher risk premia ex post. If our measures could therefore incentivise banks to start competing again for good credit, rates would start to fall and this cycle could be put into reverse.

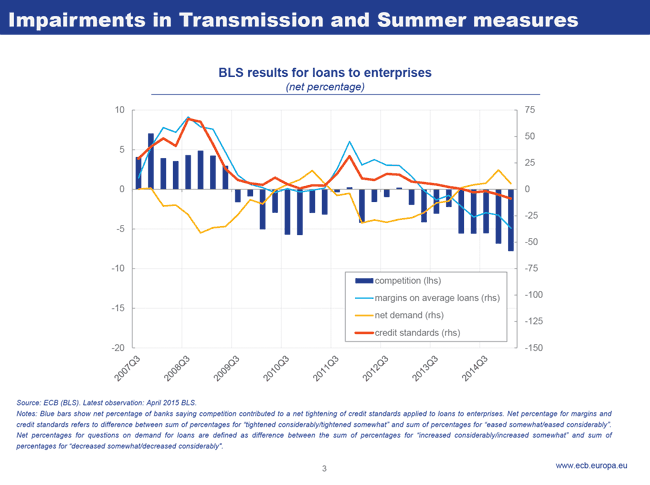

As the credit easing programme has gathered steam, this is indeed what we have seen. Our bank lending survey confirms that competition for good credit among banks has increased. This has squeezed margins and caused bank lending rates to fall. Lower rates have in turn created more net demand for borrowing. And banks have then begun to search for the “next tier” of borrowers, leading to a gradual easing of credit standards and – we expect – a further strengthening of competitive pressures (Chart 3).

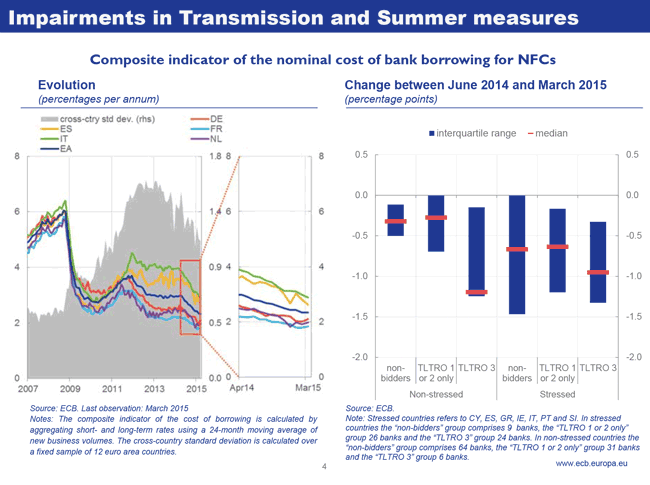

Importantly, this process has been driven predominantly by banks that have drawn on the TLTROs and has been operative in both stressed and non-stressed countries. As a result, it has led to a convergence in the cost of borrowing across euro area countries, with measures of dispersion in average lending rates approaching levels unseen since the start of the sovereign debt crisis (Chart 4).

Chart 3: Effect of TLTROs on determinants of credit supply and demand

Chart 4: Overall impact of credit easing package

2. Moving into the third contingency

In the latter part of last year, however, the inflation outlook for the euro area began to materially deteriorate, as I acknowledged in a speech I delivered in Jackson Hole. [2]

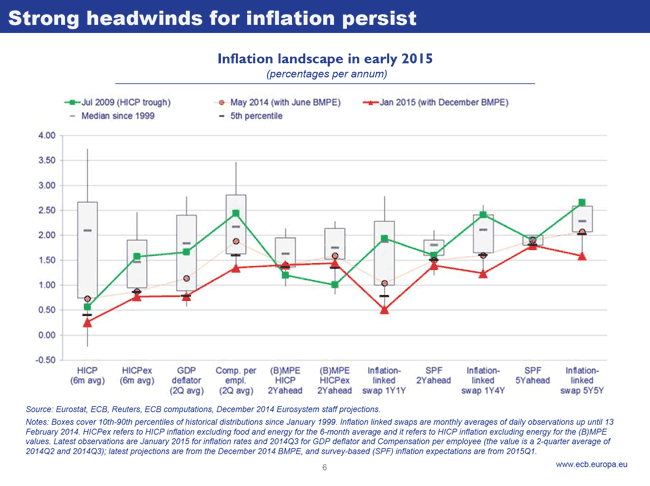

The macroeconomic situation worsened unexpectedly over the summer as the underlying impetus that we saw earlier in the year faded (Chart 5, rhs). This removed an important force behind the reflation scenario we had expected. The sharp fall-off in oil prices that began in late summer then added further disinflationary pressures, feeding also into core inflation (Chart 5, lhs). The result was that, by January 2015, the euro area was experiencing negative headline inflation rates and a generalised decline in measures of actual and expected inflation. And while the medium-term orientation of our monetary policy strategy allows us to “look through” such price developments if they are temporary in nature, there were two reasons why we feared this would not be the case.

First, while the fluctuations in inflation in the second half of the year were clearly being driven by supply factors, there were strong signs that the trend was being driven by weak aggregate demand. This was visible both at the macro level in a still wide output gap and a declining rate of core inflation; and at the micro level in subdued negotiated wages and low pricing power among firms. In other words, we were not facing merely a downward shock to prices, but also a downward shock to inflation dynamics – a sustained adverse development.

Chart 5: Macro and inflation landscape in early 2015

Second, because of this weak underlying trend in inflation, there was a higher risk that the oil price fall could feed into second round effects. Indeed, several factors suggested that the situation was more worrying than past episodes of oil-induced disinflation, particularly the most recent case in 2009 following the collapse of Lehman brothers. Our analysis showed that the persistence of low inflation across a range of statistical metrics was higher than in 2009. Inflation expectations had also become, at all horizons, less well anchored to our objective and more sensitive to that low realised inflation, whereas in 2009 they hardly moved at all. And measures of core inflation had become less sticky, implying a higher risk that this low realised and expected inflation would become entrenched in wage setting behaviour (Chart 6).

Also relevant was the fact that this loosening of inflation expectations occurred while policy rates were already at the effective lower bound. At the lower bound a fall in inflation expectations implies a rise in real interest rates, so this development risked generating a contractionary effect that would offset, at least in part, the benefits of the fall in oil prices. Moreover, given high debt levels in parts of the euro area, this would be amplified if second round effects set in and real debt burdens increased, as borrowers tend to have higher propensities to consume and invest than lenders.

Chart 6: Inflation landscape in 2009 and 2015

It was in this context that we moved into the third contingency by engaging into outright asset purchases. This began in September 2014 with our announcement that we would purchase asset-backed securities and covered bonds. And it was then scaled up in January 2015 with the addition of public sector securities to our purchase programme. These asset purchases work in two main ways.

First, they have a signalling effect, which contributes to re-anchoring inflation expectations more in line with our medium-term objective. This has been instrumental in reversing the rise in real interest rates that we observed at the start of this year. The euro area spot 5-year real interest rate had increased by around 60 basis points between September 2014 and January 2015; it then fell by 85 basis points between mid-January and April. The signal that liquidity will keep expanding is also supporting a flattening of the term structure, thus further reducing real rates out along yield curve. In addition, as this contributed to the diverging paths of monetary policy across jurisdictions, it also put downward pressure on the exchange rate.

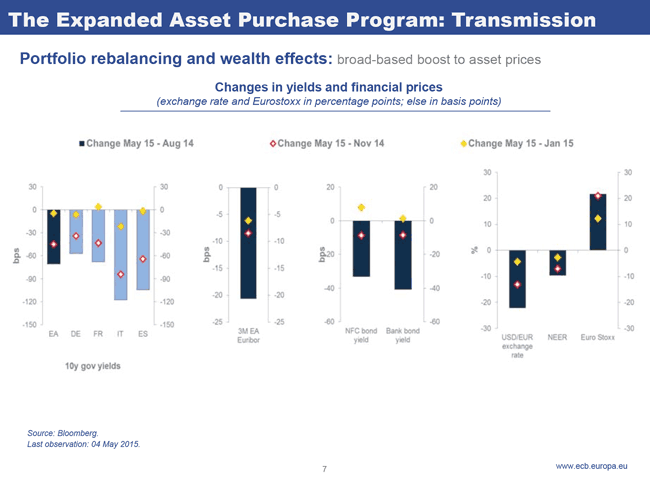

Second, even though we purchase only a comparatively narrow range of high-quality securities, our purchases have a direct and indirect effect across the whole financial system, through a portfolio balance effect. They not only alter the price of risk-free securities, which forms the basis for the pricing of all financial instruments. They also generate scarcity in the market in which we buy, which encourages investors to shift holdings into other asset classes – e.g. from sovereign to corporate bonds, from debt to equity, and across jurisdictions, reflected in a falling of the exchange rate (Chart 7). In combination, a lower cost of debt finance, a lower cost of equity and a lower exchange rate all contribute to making investment projects profitable that were previously deemed unattractive.

Chart 7: Portfolio rebalancing effects

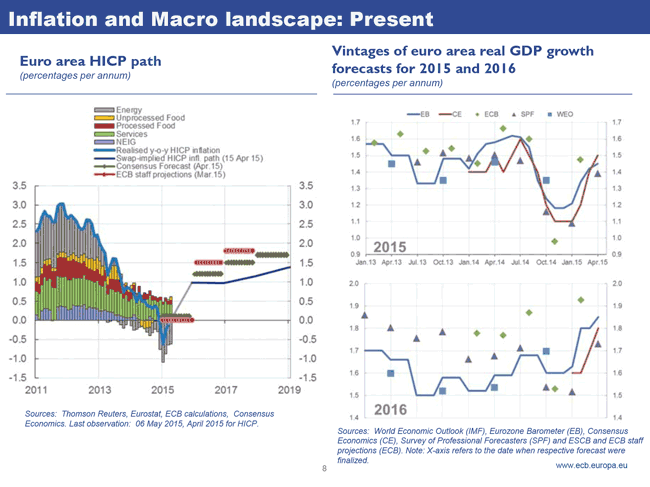

As a result of the comprehensive easing cycle from June 2014 to January 2015, both the inflation and growth outlook have improved considerably and consumer confidence is now on the rise (Chart 8). And this may indeed have come as a surprise to some observers: one of the key objections to our programme was that it would be ineffective in a low interest rate environment and/or following a balance sheet recession.

An important reason why this objection has proven questionable, in my view, is that it concentrated exclusively on the interest rate channel of transmission. What we can see, however, is that the other transmission channels of large-scale asset purchases are meaningful. The portfolio balance effect is still powerful in a bank-based economy and when interest rates are low or even negative – indeed, it is perhaps even more powerful in this environment as investors are displaced into more risky asset classes, such as equity. And when there is high uncertainty, signalling effects can become commensurately stronger if well-timed and clearly communicated.

While we have already seen a substantial effect of our measures on asset prices and economic confidence, what ultimately matters is that we see an equivalent effect on investment, consumption and inflation. To that effect, we will implement in full our purchase programme as announced and, in any case, until we see a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation. After almost 7 years of a debilitating sequence of crises, firms and households are very hesitant to take on economic risk. For this reason quite some time is needed before we can declare success, and our monetary policy stimulus will stay in place as long as needed for its objective to be fully achieved on a truly sustained basis.

Chart 8: Macro and inflation landscape in early 2015

3. Collateral consequences of monetary policy

A prolonged period of accommodative monetary policy can, however, come with side effects. And the fact that our policy has so far proven effective should not blind us to them.

This is not a question of trade-offs. We cannot shy away from implementing a policy that ensures price stability on account of potential collateral effects. Nor can we extend the medium-term to horizons that compromise our objective. Yet at the same time we need to understand and manage those collateral effects – and in pursuing our mandate we should attempt, to the extent possible, to minimise them. Where this is not possible, we have a duty to raise awareness so that mitigating or corrective action can be taken by other relevant authorities.

So in this context, I would like to address specifically two concerns that have arisen about the possible collateral effects of our actions. These are the consequences for allocation and distribution.

In terms of allocation, a key concern at the present time is that very loose financing conditions could result in a misallocation of resources, which would ultimately undermine financial stability. In particular, it has been suggested that a prolonged low rate environment can lead to excessive financial risk-taking, delayed balance sheet repair and, ultimately, a form of financial dominance as the pressure on the central bank to delay a normalisation of monetary policy increases. I can of course see the logic to these arguments: a long period of very low interest rates is potentially conducive to imbalances. But it is important to underline two points.

First, one has to analyse carefully the balance of effects between monetary policy and financial stability. For example, in a debt overhang environment it is not clear that accommodative monetary policy is inimical to balance sheet repair. In many countries low interest rates have in fact helped stabilise debt dynamics via reduced interest rate burdens, and thereby facilitated balance sheet adjustment. The interest spending-to-GDP ratio of euro area governments has declined on average by 0.4 p.p. of GDP between 2012 and 2014. Similarly, the debt burden of households and firms has fallen and reduced bank funding costs have contributed positively to retained earnings, which accelerates the deleveraging of bank balance sheets. All this makes it easier for monetary policy to normalise over the medium-term.

Second, our monetary policy decisions have not been taken in a vacuum – they have been taken in the context of a broader policy framework that helps mitigate some financial stability concerns. For instance, our recent measures were launched against the backdrop of the Comprehensive Assessment of bank balance sheets, which included an asset quality review of unprecedented depth and breadth. Our monetary policy has therefore been associated with both de-risking and de-leveraging of bank balance sheets, not the opposite. [3] Moreover, we are now operating in a new regulatory and supervisory environment, including the creation of a European banking supervisor in the SSM, which has been specifically designed to reduce capture and temper pro-cyclicality. And remember it is banks that historically have been at the centre of the most serious financial crises.

While we are monitoring developments closely, at the moment there is little indication that generalised financial imbalances are emerging. As a matter of fact, the two most important indicators of growing financial imbalances – real estate prices and credit growth – show only tentative signs of turning upwards. What this underlines is that following a major financial crisis accommodative monetary policy does not necessarily blur a prudent assessment of risk. On the contrary, it can help produce a more regular pricing of risk, which may have become too high and adverse to productive risk-taking.

In sum, while a period of low interest rates will inevitably result in some local misallocation of resources, it does not follow that it has to threaten overall financial stability. This hinges crucially on monetary policy being embedded in a complementary set of supervisory and regulatory policies that create incentives for balance sheet adjustment and responsible financial behaviour.

Another concern, which has accompanied the fall of interest rates to their effective lower bound and the introduction of unconventional measures, is the distributional consequences of monetary policy. In particular, there have been concerns that very low rates for a prolonged period might penalise savers to the benefit of debtors; or that rising asset prices as a consequence of our purchases might benefit the wealthy disproportionately and thereby increase inequality.

Distributional matters are complex, and even more so in the context of a heterogeneous monetary union. I will therefore limit myself to a few remarks on the matter.

First of all, it is important to make clear that there are also distributional effects from monetary policy inaction – from the central bank not meeting its mandate or, in other words, from realised inflation persistently deviating from the central bank’s objective. In the case of an unexpected undershooting of inflation, data for the euro area suggest that younger households (from 16 to 44 years old) would be most affected. They tend to be net debtors, with debt denominated in nominal terms, and are therefore most exposed to rising real debt burdens. In contrast, older households tend to have positive net wealth, some of it held in nominal assets. Inflation undershooting therefore results in redistribution from younger to older households. This empirical observation applies not only to the euro area as a whole, but also to most individual countries. [4]

Secondly, there are always distributional consequences to monetary policy decisions. When monetary policy acts to stave off disinflation by lowering interest rates, this has inevitably a distributional effect by reducing the interest income of savers and lowering the debt burden of borrowers. But such interest rate cuts are necessary to raise aggregate demand by encouraging firms and households to bring forward spending decisions – that is, they discourage excessive savings and incentivise investment by lowering the cost of finance. Moreover, to the extent that borrowers tend to have higher propensities to consume and invest than lenders, such distributional effects may be helpful for the recovery.

I would look at the question of rising asset prices from the same perspective. It is true that our low policy rates, forward guidance and asset purchases raise the current market value of financial assets and thereby benefit the holders of those assets. But what matters more is the exact mirror effect of this rise in asset prices, which is a lower cost of equity for entrepreneurs, a lower cost of finance for investors in real projects, and a lower cost of borrowing for consumers.

That being said, we have to be mindful that too prolonged a period of very low real rates can have undesirable consequences in the context of ageing societies, where many households save not just to smooth consumption over the cycle, but to smooth consumption over their lifetime. For pensioners, and for those saving ahead of retirement, low interest rates may not be an inducement to bring consumption forward. They may on the contrary become an inducement to save more, to compensate for a slower rate of accumulation of pension assets.

However, I would submit that it would not be in the genuine interest of those savers if the central bank gave up on its mandate. On the contrary, the interest of long-term savers is that output be raised to potential without undue delay. This is because their financial assets are always, in the final analysis, a claim on the wealth generated by the productive part of the economy. So it is in their interest that output growth remains on a robust path as this maximises the likelihood that their claims are honoured in full. At the same time, the more monetary policy is able to encourage investment, the faster interest rates will return into more normal territory.

4. Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Faced with an environment of unprecedented complexity, the ECB has taken a series of unconventional measures to prevent a too prolonged period of low inflation and deliver its mandate. Those measures have proven so far to be potent, more so than many observers anticipated. But their potency is also because they have interacted with other policies that have put the economy and the financial sector in a better position to respond to our monetary impulses.

This includes the Comprehensive Assessment of euro area banks. And it includes structural reforms where they have been implemented. By the same token, structural reforms that increase confidence in economic prospects and encourage entrepreneurs to capitalise on today’s extremely accommodative financing conditions will make our policy commensurately more powerful.

Policymakers in the euro area are independent, but the effects of their policies are interdependent. This is why it is ultimately only a combination of policies, that are complementary and mutually consistent, that will allow our policy to reap its full effects – and to bring about a lasting return of both prosperity and stability for the whole euro area.

[1]See speech by Mario Draghi, Monetary policy communication in turbulent times, at the Conference De Nederlandsche Bank 200 years: Central banking in the next two decades, Amsterdam, 24 April 2014.

[2]See speech by Mario Draghi, Unemployment in the euro area, annual central bank symposium in Jackson Hole, 22 August 2014.

[3]More generally, Homar and Van Wijnbergen (2014) find that recapitalisation and liquidity provision are complementary in speeding up the recovery after financial crises. See Homar, Timotej and Sweder van Wijnbergen (2014), “On Zombie Banks and Recessions after Systemic Banking Crises: Government Intervention Matters”, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 13-039/IV/DSF54.

[4]See Adam, Klaus and Junyi Zhu (2014), “Price Level Changes and the Redistribution of Nominal Wealth Across the Euro Area”, Working Papers, No. 14(11), University of Mannheim.

Evropská centrální banka

Generální ředitelství pro komunikaci

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Německo

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukce je povolena pouze s uvedením zdroje.

Kontakty pro média