Monetary policy, credit flows and small and medium-sized enterprises

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB

San Casciano Val di Pesa, 18 October 2009

I would like first of all to thank the organisers of this event for their invitation, which allows me to speak about monetary policy, credit developments and the situation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the euro area.

I will structure my comments as follows: after briefly outlining the importance of SMEs in the euro area, I will examine the situation in the banking sector and discuss some aspects of the process of bank restructuring in the euro area. I will look at bank lending developments in the euro area, before analysing some of the evidence on SMEs’ access to finance which emerged from a recent survey conducted by the ECB. I will conclude with some observations concerning the economic outlook and the role that monetary policy can play in this context.

In brief the main conclusions are as follows: first of all, the situation in the euro area banking sector improved in the first half of 2009. Nevertheless, a number of considerable risks remain, some of which might even have increased. Second, the volume of bank loans to the non-financial private sector has been modest in recent months. That said, given the severity and duration of the recent crisis, this trend does not deviate particularly from the empirical regularities observed for previous economic cycles. Third, the survey on SMEs indicates that, despite having been less successful than large companies as regards their applications for bank loans in the first half of 2009, the majority of SMEs received some or all of the amount applied for. Fourth, it is probable that loans to non-financial corporations will remain modest over the coming months; this would be in line with past evidence, which suggests that the trend of such loans tends to lag developments in GDP by a few quarters. Fifth, the ECB has introduced numerous measures, both ordinary and extraordinary, to support the euro area economy in general and the banking sector in particular. It would be difficult to do more. It is now time for the banking sector to implement the necessary process of recapitalisation in order to restore confidence and support growth.

The importance of SMEs in the euro area

Let me start by pointing out the importance of SMEs in the euro area. SMEs – which are usually defined as firms with less than 250 employees – play a very important role: over 99% of firms are SMEs and, in the non-financial corporate sector, they produce 60% of total turnover and employ 70% of employees. Their activities are essential to fostering entrepreneurship, competition, innovation and growth.

Examining this sector is important for the ECB because there are differences between SMEs and large firms with regard to the transmission of monetary policy, owing in particular to the fact that SMEs are more dependent on bank financing than large firms. It thus follows that the financing conditions faced by SMEs are linked especially closely to the situation in the banking sector, and in particular to that of small banks, which are the main lenders to SMEs. On the other hand, banks generally face greater difficulties when assessing the creditworthiness of SMEs. This relative opaqueness may be countered to some extent by “relationship lending”, which enables the bank to build up expertise over time with regard to the business and the financial situation of its borrower.

The euro area banking system

Before examining SMEs’ access to bank finance in greater detail, I would like to look at the situation in the banking system. I will focus on banks’ deleveraging during the past few quarters and the effects on banks’ earnings as well as their capital ratios. In addition, I will compare the lending behaviour of large banks with that of smaller banks.

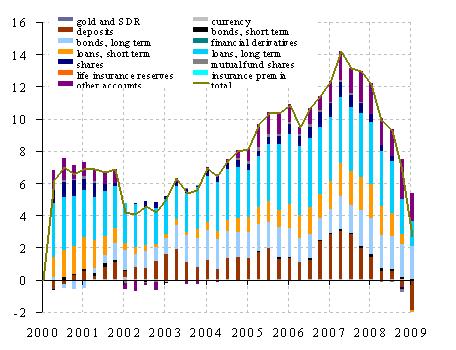

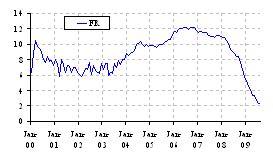

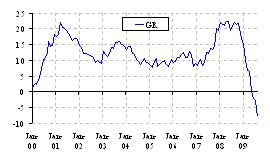

Since the start of the financial turmoil in the third quarter of 2007, banks have begun to scale down their investment in financial assets, as seen in Chart 1. This behaviour is in sharp contrast to the intense accumulation of financial assets observed previously and reflects the adjustment of banks’ balance sheets in the context of the general deleveraging process. The decline in the annual growth rates of assets has been most visible in short-term loans and deposits as well as in liquid assets, such as equities and mutual fund shares. The sharp contraction in interbank deposits has mainly reflected the freezing of the interbank market following the onset of the financial turmoil, in the context of which euro area monetary financial institutions (MFIs) withdrew their short-term deposits placed at banks. In addition, euro area banks have scaled down their deposits with other counterparts outside the euro area. As well as downsizing their external assets, banks initially scaled down their investment in marketable assets. By contrast, partly related to “relationship banking”, the growth rates of long-term loans have held up. Banks’ investment in long-term debt securities even accelerated in early 2009; indeed, MFIs stepped up their purchases of government debt securities, reflecting the generous liquidity situation in an environment of heightened risk aversion.

While the slowdown in the growth rate of assets in principle limits the earning capacity of banks, other factors contributed in the first half of 2009 to a marked improvement in the profitability of large banking groups in the euro area. Net interest income was the main factor behind this improvement, owing to the positive slope of the yield curve and wider operating margins. In addition, trading income recovered strongly as financial markets rebounded after the first quarter of 2009. Finally, revenues from fees and commissions held up remarkably well throughout the financial turmoil.

At the same time, a number of significant risks remain and some may have even increased. First, the slowdown in the growth of assets held by euro area banks limits their future earning capacity in terms of interest and investment income. Second, a deterioration in the credit quality of borrowers may put a drag on banks’ future earning capacity. In fact, while large and complex banking groups seem to be gradually absorbing the losses they suffered on their securities holdings, driven in part by the reclassification of assets, they have reported sharply higher provisions for loan losses.

Let me now turn to capital ratios. The recovery in the earnings of large and complex banking groups in the euro area, together with a slowdown in the growth rate of both risk-weighted and total assets and an increase in capital, from both public and private sources, has meant that the capital ratio of the average banking institution has typically been relatively stable. There is, however, considerable divergence between groups. A somewhat reassuring finding is that the institutions which reported the largest increases in loan loss provisions also seem to have the highest capital buffers. This may mitigate the solvency risks originating from deteriorating asset quality in the future.

A breakdown of banks by size

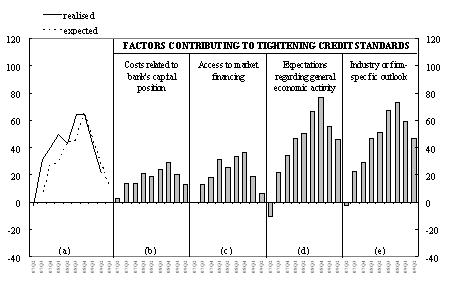

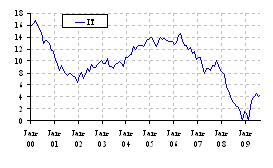

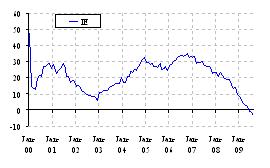

Against this background, it is not surprising that banks’ balance sheet constraints played a greater role during the recent financial turmoil, leading to a tightening of credit standards by banks, as shown in Chart 2.

The bank lending survey for the euro area, from which this information is taken, distinguishes between large banks and smaller banks. In particular with respect to the greater relevance of smaller banks for SME financing, it is therefore of interest to distinguish between the lending of large banks and that of smaller banks in the euro area. Since mid-2007, and in particular during the initial phase of the financial turmoil, large banks have overall tightened their credit standards for loans to enterprises somewhat more than smaller banks. The outlook for the economy in general and for individual firms contributed most to the tightening, in Italy as well as in the euro area as a whole.

The deteriorated access to capital market financing during the financial turmoil contributed significantly to the tightening of credit standards. It played a much more important role for large banks than for smaller banks, which rely less on capital market financing. The difficult liquidity conditions in the market also played a somewhat more important role for large banks, possibly because money market financing represents a greater share of their overall financing. All this may explain why the net tightening of credit standards was greater for large banks than it was for smaller banks.

However, both large and smaller banks tightened their credit standards more on loans to large firms than on loans to SMEs. This was especially the case at the beginning of the financial turmoil, but the net tightening was still slightly stronger for large firms in the second quarter of 2009. This may be surprising, given that there is a general perception that access to finance has of late become more difficult in particular for SMEs.

The pattern of a stronger net tightening for loans to large firms can also be observed in Italy. This indicates that both large banks and large firms, which rely more on market-based financing, were initially more strongly affected by the financial turmoil than smaller banks and SMEs.

Since the second quarter of 2008, however, the differences in lending behaviour between large and smaller banks have diminished. This probably indicates that the economic downturn has played a major role in the general tightening of standards when evaluating the creditworthiness of firms.

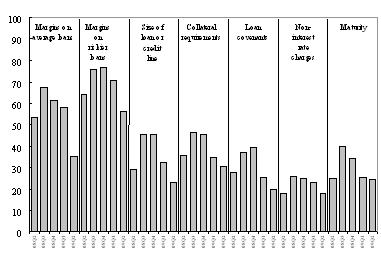

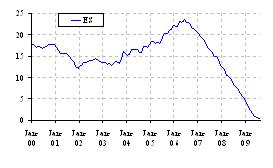

Let me now turn to the question of how banks have tightened their credit standards. Both large and smaller banks have done so predominantly by increasing loan margins. In Italy, the net tightening of margins on average loans was similar to that for the euro area as a whole.

At the euro area level, large banks increased margins on loans to enterprises somewhat more than smaller banks, which is in line with the overall stronger net tightening of credit standards. The increase in margins was particularly pronounced in 2008, but was lower in 2009, as illustrated by Chart 3. Besides the increase in margins, the non-interest terms and conditions of bank loans were also tightened considerably by banks. As examples, let me mention the increasing collateral requirements and loan covenants, as well as rises in non-interest charges.

This is in line with evidence from a survey on the access to finance of SMEs in the euro area, which I will shortly discuss in more detail. However, I would like to mention at this point the results of the SME survey with respect to the development of the terms and conditions of bank loans in the first half of 2009. The bank lending survey and the survey on SMEs’ access to finance present an overall similar picture.

For the first half of 2009, euro area SMEs point especially to a deterioration in the non-interest terms and conditions, such as charges, fees and commissions. In addition, a considerable net share of SMEs reported an increase in collateral requirements and other non-price terms and conditions, such as loan covenants and information requirements. This reported deterioration was, in net terms, much higher than that observed for interest rates. Italian SMEs also reported a tightening of non-interest terms and conditions, but – by contrast with average developments in the euro area as a whole – they reported a slight decline in interest rates. Indications of a fall in interest rates are also found in the other two large euro area countries (Germany and France) and are in line with the evidence we have from aggregate bank interest rate statistics. This somewhat more positive picture compared with the euro area average indicates considerable heterogeneity of developments across countries, to which I will return in a few minutes.

Bank lending in the euro area

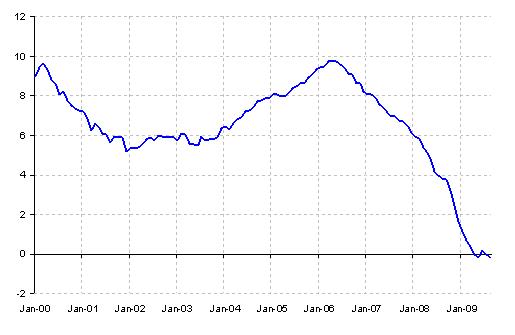

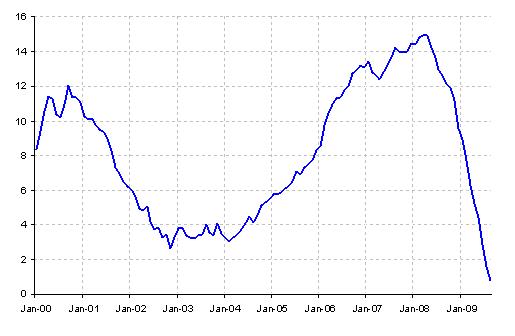

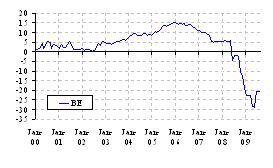

Let me now turn to actual developments in bank loans in the euro area. The growth of banks loans to the private sector has declined considerably during the financial turmoil, and in recent months the volume of lending has reached the lowest levels seen since the early 1980s, as can be seen in Chart 4. In the case of households, there have been recent signs that the downward movement has come to a halt. More precisely, the annual growth rate of loans to households has gradually fallen from the peak recorded in April 2006, when it stood at close to 10%, to levels of close to zero in recent months (-0.2% in August 2009) (see Chart 5). However, if the distortionary effect of the derecognition of loans on banks’ balance sheets related to the securitisation of loans to the private sector is taken into account, the growth of loans to households appears to be still positive and stabilising. The annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations, by contrast, fell from its recent peak of almost 15% in April 2008 to 0.7% in August 2009 (see Chart 6). It should be noted that these figures cover all non-financial corporations, small, medium-sized and large, and do not provide a breakdown of the data by size of firm. In the case of non-financial corporations, the moderation in lending has thus continued, a fact which has raised some concerns among market observers that companies, and SMEs in particular, may be suffering from a true “credit crunch”.

Against the background of these concerns, it is important to make a number of observations.

First, looking ahead it is likely that loans to enterprises may moderate further before starting to recover. This would also be in line with past evidence, which indicates that the growth of loans to non-financial corporations tends to lag GDP growth by about three quarters. This may be related to the fact that non-financial corporations usually see their cash flows improve early in an economic upturn and thus tend to finance working capital and fixed investment with internal funds first, and only later with external financing. Given the current projections of a stabilisation in economic activity in the second half of this year, a turning-point in loan growth may not be reached before early 2010.

Second, recent credit developments appear to be fully in line with past historical regularities, once we take into account the severity and duration of the recession. Indeed, the current crisis may be the most severe seen since the 1930s. However, caution is warranted when interpreting these developments. Not only are deviations from average historical regularities observed, but the full impact of the recent severe crisis is still uncertain.

Third, it is clear that both supply and demand factors have driven credit developments in the euro area so far, as confirmed by the evidence provided by the bank lending survey. Overall, our assessment is that credit developments have thus far been affected more strongly by factors associated with weak macroeconomic conditions, such as lower credit demand and a decrease in the average level of creditworthiness of potential borrowers. However, supply-side factors have also played a role and should not be underestimated.

SMEs’ access to finance

I will now turn to some more direct evidence on SMEs’ access to finance in the euro area provided by a recent ECB survey. This survey, which was conducted for the first time in June-July 2009, asks firms across the European Union about their financing conditions over the previous six months, meaning broadly the first half of 2009 in this case. This survey should help over time to fill the gap regarding information on the financing conditions of SMEs in the euro area, since quantitative statistics provide very little evidence on the actual situation.

I will present some of the key findings of this survey, as it provides a comprehensive picture of the financial situation of SMEs in the euro area and their access to financing over the first half of 2009. The survey evidence provides input into the discussion on constraints in the access to finance of firms, and SMEs in particular. At the same time, given that this is the first time the survey has been conducted, the results of the survey should be interpreted with caution.

I will start with the turnover and profit situation of SMEs in the first half of 2009. Thereafter, I will turn to the most interesting results of the survey in the current economic situation, namely the evidence on SMEs’ access to finance and their experience when applying for a bank loan. Last but not least, I will briefly add some evidence on the heterogeneity across euro area countries.

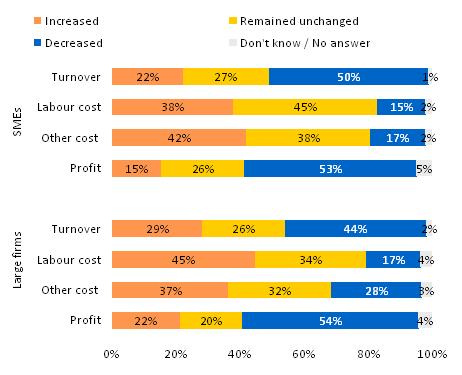

Let me start with the financial situation of firms in the euro area. Overall, SMEs’ assessment of their financial situation is more negative than that of large firms (see Chart 7). This suggests that SMEs were more strongly affected by the crisis up to the first half of 2009. For instance, a higher net share of SMEs than of large firms reported that their turnover had decreased. Turnover and cost developments had a negative impact on firms’ profits. Consequently, a higher share of SMEs than of large firms said that their profits had deteriorated in the first half of the year.

Given the economic situation, it may come as no surprise that a limited share of euro area SMEs (10%) also reported a deterioration in their own capital (the share of large firms reporting a decline was lower).

These developments certainly had an impact on the response to applications for bank loans and, more generally, on the availability of bank loans to euro area firms in the first half of 2009.

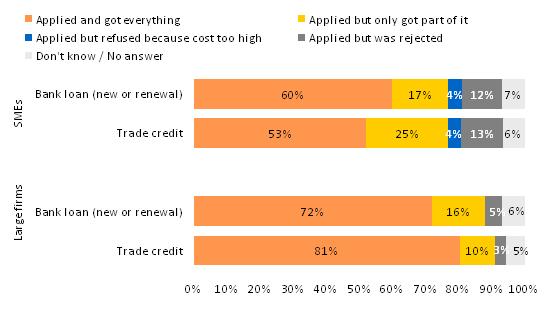

Notwithstanding the deterioration in the economic situation, the majority of SMEs report that they were successful in applying for a bank loan in the first half of 2009 (see Chart 8). This is one of the main findings of the survey. It provides a very useful overall picture of bank loan supply and helps to answer the question of whether SMEs experienced financing constraints in the first half of 2009. In the period under review, 60% of the SMEs that had applied for a bank loan received the full amount they had requested. An additional 17% said they had received at least part of the amount requested, so that 77% of SMEs received either all or part of the requested bank loan. By contrast, 12% of SMEs had their bank loan application rejected.

Unfortunately, we are not yet in a position to compare these results over time to assess whether these shares are high or low. Still, even in times of sound economic growth, some SMEs will always be unsuccessful in obtaining the financing they have applied for, for reasons such as insufficient business plans. However, there seems to be a clear relationship between the size and age of a firm and its success in applying for a loan. The larger and older the firms were, the more successful they were in obtaining a loan. Indeed, about twice as many applications for bank loans by SMEs as those by large firms were rejected.

Availability of external financing

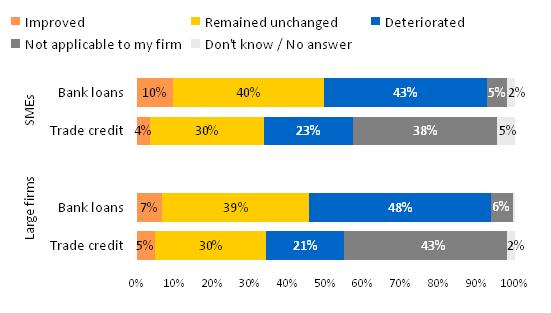

Firms that had an external financing need and therefore had applied for a loan in the first half of 2009 were rather sceptical in their assessment of the availability of external financing (see Chart 9). Large firms were somewhat more negative in their assessment than SMEs. This is in line with the evidence from the bank lending survey that the tightening of credit standards was more pronounced for large firms than for SMEs. As already mentioned, this may come as a surprise, as SMEs are generally perceived to be affected more than large firms by a deterioration in access to finance.

The availability of bank loans tends to be related to the general economic situation, which affects the financial situation of the individual firm. Hence, it is not surprising that both factors played a major role in bank loan availability, not only according to the assessment of banks in the bank lending survey, but also according to the assessment of firms in the new survey. However, in addition to such demand-related factors, firms are of the view that factors related to the supply of credit also played some role in the deterioration of bank loan availability. In their view, banks’ willingness to lend decreased, which may suggest that lending restrictions were in place.

The situation in the largest euro area countries

Let me now touch on some of the main results for the largest euro area countries. While overall developments are most important for the ECB’s monetary policy, it is also worth examining the considerable heterogeneity across different countries in the access to finance of SMEs in the first half of 2009.

Regarding turnover and profit, SMEs in Germany and France were above the euro area average, in the sense that fewer SMEs reported a net deterioration. SMEs in Italy were around the euro area average, but those in Spain were far below the average. The economic situation is clearly reflected in SMEs’ assessment regarding the deterioration in the availability of external financing. Again, SMEs in Germany and France reported a smaller deterioration in the availability of bank loans than the euro area average. The figure for Italy was slightly better than the euro area average, while Spanish SMEs were much more negative in their assessment of their access to bank loans. A similar picture emerges when investigating the success of applications for bank loans. While Spanish SMEs reported a lower success rate, French firms reported the highest, followed by Germany and Italy.

In sum, comparing the data on bank loans with the results of the survey on SMEs, it is possible to conclude that the modest growth in bank loans granted to the non-financial private sector in recent months is mainly due to the weak macroeconomic conditions. However, it has also been affected to some extent by supply-related factors, which have had a negative impact on bank lending conditions.

Some forward-looking considerations

Let me finally turn to some forward-looking considerations and the role that monetary policy can play.

According to the forecasts of the main international organisations, the economic recovery is likely to proceed gradually and unevenly, in a context of continued high uncertainty and possible further deleveraging on the part of banks. Further ahead, as the economic recovery strengthens, banks should be in a position to enhance their capital ratios, thereby increasing their capacity to provide loans.

I would like to refer in this respect to the latest guidelines of the Basel Committee with regard to capital requirements and the implementation of Basel II. Regulatory capital requirements are central to our discussion, as there are clear links between banks’ capital management, the loan-granting process and credit supply. While a stronger alignment with actual economic risk is necessary, it is also important that the new requirements do not imply excessive pro-cyclicality. When I speak of “pro-cyclicality”, I am referring to the interactions between the financial and real sectors of the economy, which tend to be mutually reinforcing and to amplify business cycle fluctuations. Just as a period of economic growth will tend to be accompanied by excessive risk-taking on the part of financial institutions, strong credit growth, asset price bubbles and, ultimately, the building-up of systemic risks, a strong contraction in economic activity may lead to a marked slowdown in financial flows, including credit, which hinders the recovery. Pro-cyclicality implies that capital requirements are loose in a boom, allowing banks to lend more in relation to their capital, while they are tight in a downturn, which induces banks to cut back lending to the private sector even further than they would in the absence of these requirements. While these mechanisms are to some extent justified by the different degrees of risk prevailing in the different phases of the business cycle, it is important that they do not lead to the excessive effects I just described.

The pro-cyclical impact of regulatory capital requirements is currently being analysed by the relevant authorities, including the ECB. These assessments could provide a basis for developing an appropriate counter-cyclical buffering mechanism, which is a precondition for enhancing financial stability over the medium to long term.

Beyond regulatory capital requirements, euro area banks need to stabilise their earnings streams so that organic capital growth can be restored, solvency ratios can be safeguarded and asset growth can gradually resume. As I have already mentioned, in order for credit markets to recover, it is not only credit supply that will need to expand, but also – and possibly to a larger extent – credit demand, which depends on several factors, including GDP growth, unemployment and inflation, which in turn affect the expectations of banks’ customers.

As regards the role of monetary policy, the exceptional circumstances related to the financial crisis led to the introduction of extraordinary measures. Our aim was to support the liquidity in the financial system and (indirectly) to enhance the flow of credit to the private sector, above and beyond what could be achieved through policy interest rate reductions alone. In particular, we have fully accommodated banks’ liquidity needs at fixed interest rates, we have further expanded the list of collateral that we accept in our operations and we have provided liquidity for longer periods, of up to one year. Through such one-year refinancing operations, we provided €442 billion in June and an additional €75 billion two weeks ago. In addition, we have provided liquidity in foreign currencies, notably the US dollar, to address the needs of euro area banks to fund their dollar assets. Finally, we have been buying covered bonds directly since July this year, as this market segment is an important source of funding for banks. This has led not only to a reduction in the interest rates on such transactions, but also to a revival in a market which had dried up, or even to the establishment of such markets in countries where they did not yet exist, such as Italy.

It is difficult to ask more of monetary policy in a market economy. Our role is limited to the provision of liquidity to solvent banks. This role does not include the recapitalisation and restructuring of the banking system, which is an important step to restore trust in the financial sector. We expect banks to take a more active role in the process of recapitalisation. As the ECB has stressed a number of times, banks must take full advantage of government measures to support the banking sector, in particular as regards recapitalisation, not least because the banking system cannot be supported indefinitely by the extraordinary measures taken by central banks. An exit strategy will inevitably need to be implemented in due course. Banks which decide not to make use of government support measures must find alternative sources, in the market, in order to be ready to step up their lending to the real economy once the recovery begins. While the slowdown in bank lending observed in recent months can perhaps in part be explained by the fall in economic activity, the failure of banking flows to pick up when demand recovers would be more difficult to justify. It would then be difficult to justify a situation in which individual incentives, those of bank managers and shareholders, are not aligned with the collective incentives to support the economy. We should not forget the experience of Japan over the past decade, where delays in restructuring and recapitalising the banking system undermined the recovery after the crisis.

I am certain that this will not happen in Europe, if all parties play their part responsibly and are conscious of the role that each component of the economic and financial system must perform, in particular when faced with critical circumstances such as those we have experienced recently. For our part, I believe that the European Central Bank has demonstrated over this period that it is living up to its responsibilities.

Thank you for your attention.

Chart 1: Euro area MFI sector’s financial assets transactions

(percentages)

Source: ECB Euro Area Accounts.

Chart 2: Changes in credit standards applied to the approval of loans or credit lines to enterprises

(net percentages of banks contributing to tightening standards)

Source: Euro area bank lending survey. Notes: The net percentage refers to the difference between the sum of the percentages for “tightened considerably” and “tightened somewhat” and the sum of the percentages for “eased somewhat” and “eased considerably”. The net percentages for the questions related to the factors are defined as the difference between the percentage of banks reporting that the given factor contributed to a tightening and to an easing.

Chart 3: Changes in terms and conditions for approving loans or credit lines to enterprises

(net percentages of banks reporting tightening terms and conditions)

Source: Euro area bank lending survey.

Chart 4 - MFI loans to the private sector in the euro area

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Chart 5 - MFI loans to households in the euro area

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Chart 6 - MFI loans to non-financial corporations in the euro area

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Chart 7: Financial situation of euro area firms, change over the preceding six months

(percentages of respondents)

Source: ECB/European Commission survey on the access to finance of SMEs.

Chart 8: Outcome of the applications for external financing by euro area firms over the preceding six months

(percentages of firms that have applied for external financing)

Source: ECB/European Commission survey on the access to finance of SMEs.

Chart 9: Availability of external financing for euro area firms, change over the preceding six months

(percentages of respondents)

Source: ECB/European Commission survey on the access to finance of SMEs.

Background charts:

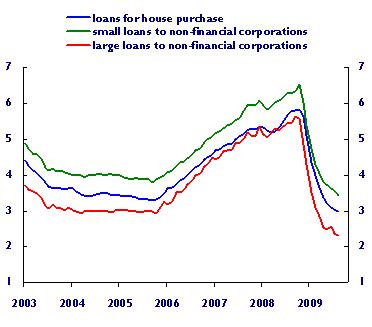

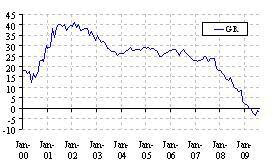

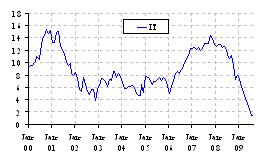

Chart A: Short-term MFI interest rates on new loans

(percentages per annum, monthly averages)

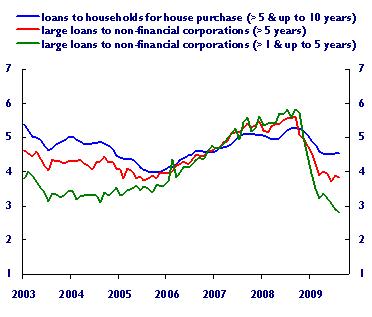

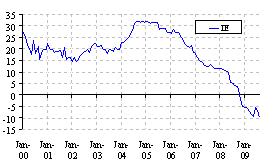

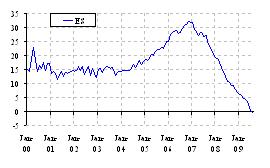

Chart B: Long-term MFI interest rates on new loans

(percentages per annum, monthly averages)

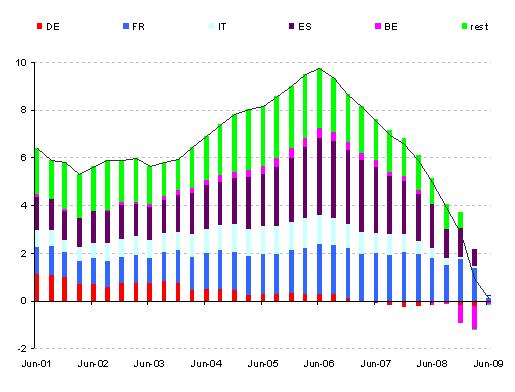

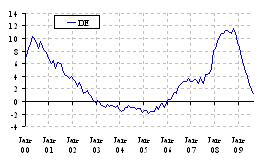

Chart C - MFI loans to households in the euro area: contributions by country

(percentage points; annual percentage changes; quarterly, quarterly data are averages, nsa)

Source: ECB.

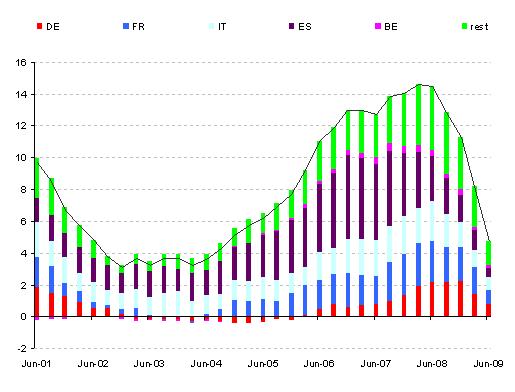

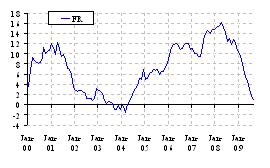

Chart D - MFI loans to non-financial corporations in the euro area: contributions by country (percentage points; annual percentage changes; quarterly, quarterly data are averages, nsa)

Source: ECB.

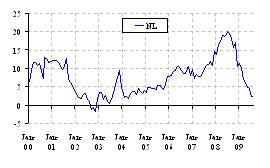

Chart E - MFI loans to households in the euro area: annual growth by country

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

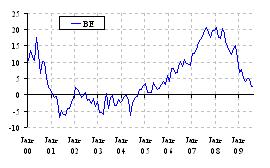

Chart F - MFI loans to non-financial corporations in the euro area: annual growth by country

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Europos Centrinis Bankas

Komunikacijos generalinis direktoratas

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurtas prie Maino, Vokietija

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Leidžiama perspausdinti, jei nurodomas šaltinis.

Kontaktai žiniasklaidai