Ladies and gentlemen,

Let me begin by thanking the conference organisers and program directors of the SAFE (Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe) Policy Center, Hans-Helmut Kotz and Jan Pieter Krahnen, for the kind invitation to speak at this 2nd Frankfurt Conference on Financial Market Policy.

The topic of this 2nd Frankfurt Conference is very well chosen. Clearly the organisers at the SAFE Policy Center recognise that the provision of credit to the euro area real economy as well as some of the risks that this may entail, also occurs beyond the regulatory perimeter of banks, a topic which was discussed in depth at the 1st Frankfurt Conference on Financial Market Policy organised last year.

I noted that you decided to name this conference “Banking Beyond Banks” rather than “Shadow Banking” which is a term that is often used. For some reason, the term “shadow banking” has acquired a pejorative connotation in some quarters. There is no justification for that. The expression “Banking Beyond Banks”, or “Non-bank Banking”, which I learnt is Hans-Helmut’s preference, on the other hand, is less of a loaded term because it implicitly also acknowledges non-banks’ contribution to the financing of the real economy.

My remarks will first focus on the non-bank banking that takes place in the euro area. I will then elaborate on some potential risks to financial stability, and end with some thoughts about regulatory challenges and macro-prudential policies aimed at managing such risks.

How much non-bank banking actually takes place in the euro area?

The FSB (2012) [1] defines shadow banking as “credit intermediation involving entities and activities (fully or partially) outside the regular banking system.”

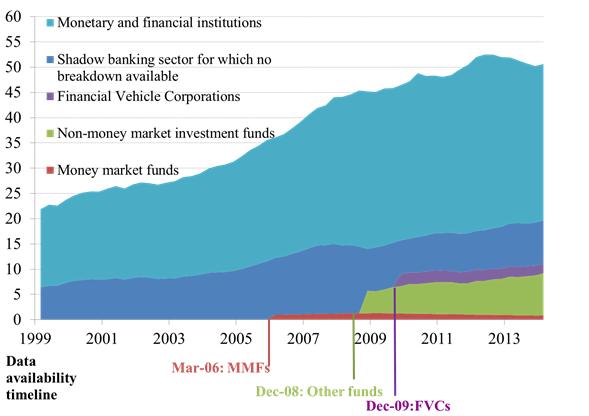

The different work streams created by the FSB to analyse the issue include indeed both entities and activities. However, in its regular Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report, the FSB focuses much more on entities that, being non-banks are involved in credit intermediation, than on activities. The reason for that is very much connected with the lack of data to do otherwise, as I will explain later. From the perspective of institutions, the broadest measure of the euro area shadow banking sector, akin to the broad measure proposed by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), refers to the assets of Money Market Funds (MMFs) and “Other Financial Intermediaries” (OFIs) that include all non-monetary financial institutions apart from insurance corporations and pension funds. According to our own estimates, which we supply to the FSB, this measure has more than doubled in size over the past decade and reached approximately EUR 19 trillion in the euro area [2] The growing importance of the sector within the financial system has gathered pace over the past two years as euro area banks have been deleveraging, while shadow banking entities, in particular investment funds, have expanded further. For instance, while the banking sector’s total assets have decreased by 11% since 2012, the total assets of investment funds have increased by 30%. Caveats must however be made about this aggregate figure since a significant residual of about 40% of the data refers to a broad and unspecified sector (institutions whose detailed balance sheet statistics are still not available). On the basis of national financial accounts and securities statistics compiled by the ECB, it is our understanding that most of this residual relates to entities located in the Netherlands and Luxembourg and is composed of single entities, holding companies or special financial institutions, that are set up mainly by non-financial corporations and that are very likely not engaged in non-bank banking because they are not involved in credit intermediation. We hope to obtain better information in the future to exclude these entities from that residual category. Similar problems occur in other jurisdictions and affect the estimated total size of the shadow banks of USD 75 trillion quoted by the FSB.

The ECB has in recent years collected balance sheet data on investment funds and financial vehicle corporations located in the euro area, and this collection has shed some light on the composition of the shadow banking system. Important changes have taken place within the system that can be linked back to three by-products of the financial crisis. First, the very low interest rate environment has created challenges for money market funds (MMFs) and their assets shrank from a pre-crisis peak of EUR 1.3 trillion to EUR 835 billion in mid-2014. Second, reflecting the collapse in securitisation activity, the assets of financial vehicle corporations involved in securitisations located in the euro area shrank by almost a third to EUR 1.9 trillion over that period. Third, the decline in money market funds and financial vehicle corporations has been more than offset by the strong growth of the euro area (non-MMF) investment fund sector. Against a backdrop of a shift towards market-based financing and, more recently, an intense global search for yield, the (non-MMF) euro area investment funds sector has rose to EUR 8.7 trillion in mid-2014.

Any monitoring of non-bank banking based on such an “entities-based approach” should however be complemented by an “activities-based approach” that focuses on intermediation activities conducted primarily through markets. What is included in this perspective are a vast array of services related to securitisation transactions, securities financing transactions (SFTs), securities lending and repos, collateral management and intermediation, the development of derivatives allowing for risk transformation and exchange via swaps, from credit default swaps to interest rate or forex swaps. Several of these activities can be conducted by regulated banks or by non-specifically regulated institutions. Basically, two aspectsmake the collection of these activities relevant: first, they contributed to the creation of a type of capital market lending system with secured short-term market funding; second, these services originate forms of liquidity instruments that are forms of money not counted in the usual monetary aggregates that we calculate.

These two features – the emergence of a new market credit system and the significance of forms of money not viewed as such – is what justifies the “shadow banking” designation. That is why some authors [3] reserve designation of shadow banking to a definition confined to this type of activities.

The origins of this new credit system are related to the emergence of very sizeable cash pools that could not find safety in banks’ insured deposits and were looking for safer ways of placing that cash in the short term. [4] Secured collateral lending and repos as well as risk transformation via swap derivatives (credit, interest rates and forex) were developed for that purpose. Securities lending for shorting and generating collateralised levered transactions for asset managers were also part of the new system. The activities of re-hypothecation and re-use of securities amplified the creation of chains of inside liquidity and higher leverage with negative consequences when the crisis led to an increase in haircuts and illiquidity in the repo market. Fortunately, the FSB has recently established a working group tasked with examining the possible harmonisation of regulatory approaches to re-hypothecation of client assets and the possible financial stability issues related to collateral re-use. In light of the underlying financial stability risks and its huge importance in financial markets, I very much welcome this work, which takes a broad and macro-prudential view on these issues.

The activity of the shadow banking sector escapes both the monetary statistics and the flow-of-funds accounts. Zolten Pozsar proposes the development of a new set of accounts to register the Flow of Collateral and the Flow of Risk. There are no good databases of securities lending or repos and they can only be developed with the collaboration of the industry as most of the operations in question are over-the-counter operations. Some time ago I launched an initiative to create such a database compiled by the ECB. Contacts with the industry and the Bank of England proved to be encouraging but other priorities imposed justifiable delays in the implementation of such an idea. What these data gaps imply is that we do not know enough about the shadow banking sector and that tackling this shortcoming must be given the highest priority.

Stijn Claessens and Lev Ratnovski (2014) [5] have suggested a criterion to pin down the activities that appropriately belong to the concept of shadow banking. The nature of those activities imply large size, reduced margins and tail risks, which means that they require some sort of private or public backstop. This relates, for instance, to the provision of liquidity lines for securitisation vehicles, the use of the banks’ balance sheets (which enjoy an implicit public backstop) to operate in the repo market [6], or still, in the same market, the so-called bankruptcy-remote privileges for lenders secured on financial collateral [7]. Without these forms of implicit public support, the repo market would not have expanded the way it did. This requirement for backstops also indicates that the border between shadow banking activities and the regulated sector is more blurred than one might have thought. One important regulatory problem of this type of shadow banking is that it has increased so much in size and is now totally internationalised and embedded in the financial globalisation that it cannot enjoy the sort of public backstops that the traditional sector used to enjoy until recently, and from which it still partly benefits. As Zoltan Pozsar writes: “The global macro drivers behind the secular rise of cash pools and leveraged portfolio managers in the asset management complex are identical with the real economy drivers behind the idea of secular stagnation. As such, one way to interpret shadow banking is as the financial economy reflection of real economy imbalances caused by excess global savings, slowing potential growth, and the rising share of corporate profits relative to wages in national income”. [8]

What I briefly described points to the fact that the regulation of these new realities is necessarily very difficult. Regarding regulatory efforts underway, the FSB has focused on five specific areas:

to mitigate the spill-over effect between the regular banking system and the shadow banking system;

to reduce the susceptibility of money market funds (MMFs) to “runs”;

to assess and align the incentives associated with securitisation;

to dampen risks and pro-cyclical incentives associated with securities financing transactions such as repos and securities lending that may exacerbate funding strains in times of market stress; and

to assess and mitigate systemic risks posed by other shadow banking entities and activities.” [9]

A few days ago, the FSB published the regulatory framework for haircuts on non-centrally cleared securities financing and repos. [10] The idea of imposing minimum haircuts in these transactions is to contain the excessive leverage created by them and also to possibly limit the subsequent volatility of such haircuts. Nevertheless, the scope of the regulation applies numerical haircut floors only to non-centrally-cleared securities financing transactions in which financing against collateral other than government securities is provided to non-banks. In addition, the framework recommends “qualitative standards for methodologies used by market participants that provide securities financing to calculate haircuts on the collateral received transactions.” The numerical haircuts vary between 0.5 % and 10% according to the type and maturity of the securities used. The immediate impact may not be very relevant but the potential role of the new instruments can become relevant.

Non-bank banking risks to financial stability

Let me now turn to the perspective of non-bank entities that perform credit intermediation and/or maturity transformation. The FSB, in the Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report [11] of last year wrote that “ Intermediating credit through non-bank channels can have important advantages and contributes to the financing of the real economy, but such channels can also become a source of systemic risk, especially when they are structured to perform bank-like functions (e.g. maturity transformation and leverage) and when their interconnectedness with the regular banking system is strong ” In my opinion, these conditions do apply as (some) shadow banking entities are indeed structured to perform bank-like functions, in part even standing in for the declining role of a deleveraging regular banking system. Furthermore, the interconnectedness of shadow banking entities with the regular banking system is strong.

The significant expansion of the shadow banking sector can present systemic risks that need to be detected, monitored and managed. Similar to the traditional financial intermediation activities of banks, shadow bank credit intermediation involves having credit exposures, normally through purchased securities, that are of a longer maturity and are less liquid than the short term and liquid nature of their liabilities. Moreover, some of these entities are leveraged, although leverage differs greatly among various entities. For instance, the majority of the investment funds that are an important part of this sector are of the open-ended type and do not face a problem of leverage but can become vulnerable because of the degree of maturity transformation they originate. In addition, many of the open-ended funds offered by asset management firms, such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs), in essence provide a promise of (almost) daily liquidity that they may not be able to deliver under stressed conditions. The combination of potentially stretched valuations in some financial market segments and low liquidity in secondary markets could represent a systemic threat when combined with a high redemption risks for funds with significant duration mismatches, low cash buffers and with direct contagion channels such as credit lines to the regular banks.

Another reason for concern stems from the fact that the shadow banking sector is highly interconnected with euro area credit institutions. Some segments of the shadow banking system play a role in the funding of the monetary financial institution (MFI) sector, while some are themselves reliant on MFIs for their funding. Therefore, difficulties in the sector can propagate quickly to the banking sector and the real economy.

Another perspective about the riskiness of non-bank banking relates not to categories of entities and their bank-like structures and activities, but to the very large footprint that some individual institutions have. Many institutions have hundreds of billions or even trillions of assets under management. We have recently observed that even ordinary events, such as personnel changes, can influence financial markets, when they concern key decision makers at very large asset management firms.

Additional regulatory concerns

I already highlighted the difficulties in understanding and regulating the elusive reality of shadow banking. To enhance this understanding, a first requisite is to require the reporting of all the necessary information for regulators so that indicators of leverage and liquidity risk for the financial system as a whole can be compiled. Several entities that are included in this concept of shadow banking, like money market funds and investment funds in general, are already subject to some form of regulation. This includes rules about the composition of assets, liquidity buffers and gates or redemption fees to contain possible runs. Regarding regulation on money market funds, I think that the Commission’s proposal is adequate whereas I doubt that the solution of generalised variable net asset value (NAVs) prevailing in the US is sufficient to contain instability episodes. Hedge funds were not at the centre of the crisis and are a business that applies high fees and benefits from investors knowledgeable about the risks they incur.

What is essential is the vigilance concerning the borders of regulated versus non-regulated entities and activities. We are aware that tighter regulations for banks have been one of the drivers of non-bank based activities. This so-called “boundary problem [12]” is not new. It arises because effective regulation penalises those within the regulated perimeter and causes a substitution of activities to entities outside the regulatory perimeter. Addressing this problem implies regulating the exposures that the regulated sector creates towards the non-banks and in the extreme a possible change of the regulatory perimeter. This change need not be for the entire non-bank sector, but placing systemically important non-banks within the perimeter should be possible. In the United States, non-bank systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) (designated by the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council) are placed under enhanced prudential supervision by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. This step has already been implemented for some institutions (such as AIG, GE Capital, Prudential Financial), while non-bank SIFI designation is being studied for some large asset managers. The FSB, jointly with the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), is currently developing methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions (NBNI G-SIFIs). I very much welcome this Too-Big-To-Fail strand of work by the FSB and IOSCO. It will help us assess this broad and heterogeneous segment of the financial system in a way that is consistent and comparable with what the Basel Committee has already done for the so-called G-SIBs (global systemically important banks) and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) plans to do for G-SIIs (global systemically important insurers). Once the methodology for identification of NBNI G-SIFI is agreed (in 2015), the discussion should move quickly to and focus on the appropriate incremental policy measures that these identified institutions should be subject to. Here, it is key to design measures that ensure that these entities internalise the potential costs they impose on the financial system, and at the same time provide for incentives to reduce their systemic footprint.

Another aspect related with the boundary problem relates to the convenience of regulating the exposures of banks to non-banks. The Basel Committee has already defined the capital charges related to equity participations of banks in non-bank institutions. Regarding simple credit exposures, the large exposures (LE) regime could play a role in protecting banks from potentially excessive exposures to the shadow banking sector and in moving contagion risk from shadow banks back into the core banking sector.

Currently, shadow banking exposures are not singled out for specific treatment within the Basel Committee’s LE Rules that were agreed on earlier this year. However, exposures of individual banks to shadow banks are subject to the general LE limit. This means that a single exposure to a shadow banking entity cannot be greater than 25% of a bank’s Tier 1 capital. Also here, we may need to go beyond and acquire additional macro-prudential tools that focus on the overall exposure to sectors, and in this context to the shadow banking sector. In the EU, the European Banking Authority is currently developing guidelines for the setting of specific LE limits to shadow banking entities across the EU (both at the individual exposure and at the aggregate level).

Another aspect that requires quicker implementation concerns the regulation of Central Counterparties (CCPs) creating a true level playing field at the international level. I already mentioned the importance of the centralised settlement of securities transactions, including repos that are at the core of shadow banking. These transactions are exempt from the regulatory minima recently published by the FSB because CCPs apply their own margin requirements. The essential questions concern the liquidity requirements that CCPs should implement and the not-yet solved problem of the resolution regime for CCPs. We are seeing a progressive significant concentration in the sector internationally and this accentuates the systemic nature of these institutions. An appropriate resolution regime that addresses the too-big-to-fail problem is becoming urgent and the ongoing work has to be accelerated.

Another aspect of the regulation could be the possibility of giving to the macro-prudential authorities the power to set countercyclical margin add-ons which CCPs need to add to the minimum requirement. This may be most relevant in ebullient times when low volatility and reduced counterparty credit risk may lead to insufficient margin requirements. When the financial cycle turns, macro-prudential add-ons can be released, ensuring higher shock absorbing capacity of CCPs.

Concluding remarks

The current process of structural change in the banking sector [13] will also have a permanent effect on the structure of intermediation in the euro area more broadly. Banks have historically played a dominant role in the financing of the euro area real economy. I expect that the future of intermediation will show some rebalancing away from the very high levels of bank-based intermediation towards more capital market-based intermediation of the euro area economy. We have over the past few years already observed the start of such a rebalancing, as euro area banks have been deleveraging, while shadow banking entities, in particular investment funds, have expanded further. This process is likely to continue in the coming years. However, I do not think that this process should go too far and completely replicate the US structure as dominance of capital market-based financing brings opportunities but also brings more volatility. From a financial stability perspective, a balanced mix between bank and non-bank banking is preferable.

Non-bank banking can indeed have a number of benefits such as enlarging the real economy’s access to credit, supporting market liquidity and enabling sharing of risk. However, non-bank banking can also be a risk to the stability of the financial system [14]. As we observed in the early stages of the global financial crisis, some highly leveraged non-bank entities, such as the broker dealers in the US, held large amounts of illiquid assets and were vulnerable to investor runs. These led to fire sales of assets which in turn depressed asset valuations and caused a contagion of stress to regular banks. In order to adequately monitor such risks and prevent them from materialising, we need to have the data that allows for an adequate assessment of leverage in the overall financial system, as well as of liquidity, maturity mismatch, and the interconnectedness between institutions both inside and outside the regulated perimeter.

Reducing contagion risk from shadow banks to the core banking sector is a challenge that requires permanent vigilance of the “boundary problem” and the use of the proper instruments to safeguard the overall stability of the financial system.

The outcome that we should strive for is to build the Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe (SAFE), surely a familiar concept here at the SAFE Policy Center of Goethe University.

Thank you for your attention.

Total assets of banks and non-banks (Q1 1999 - Q1 2014; EUR trillions)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations.

-

[1]Financial Stability Board (FSB ) 2012, “Strengthening Oversight and Regulation of Shadow Banking,” Consultative Document.

-

[2]See “Structural features of the wider euro area financial system”, ECB, Banking Structures Report, October 2014

-

[3]See among others, Shin H.S. (2009), “Financial Intermediation and the Post-Crisis Financial System”, BIS Annual Conference; Adrian T., H.S. Shin (2009), “The Shadow Banking System: Implications for Financial Regulation”, Banque de France Financial Stability Review 13:1–10; Pozsar Z., T. Adrian, A.B. Ashcraft, H. Boesky (2010), “Shadow Banking”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 458; Claessens S, Z. Pozsar, L. Ratnovski and M. Singh (2012), “Shadow Banking: Economics and Policy”, IMF Staff Discussion Notes 12/12; Mehrling P., Z. Pozsar, J. Sweeny, and D.Neilson, (2013) “Bagehot was a Shadow Banker: Shadow Banking, Central Banking and the Future of Global Finance”, Institute of New Economic Thinking; Pozsar, Z. (2014) “Shadow Banking: The Money view”, Office of Financial Research Working Paper 14-04; Claessens S. and L. Ratnovski (2014), “What Is Shadow Banking?” IMF Working Paper 14/25.

-

[4]Pozsar, Z. (2011) “Institutional Cash Pools and the Triffin Dilemma of the U.S. Banking System”, IMF Working Paper 11/190

-

[5]Claessens S. and L.Ratnovski (2014) “What Is Shadow Banking?”, IMF Working Paper14 /25

-

[6]Singh M. (2012), “Puts in the shadow”, IMF Working Paper 12/229

-

[7]Perotti E. (2013), “The roots of shadow banking”, CEPR Policy Insight 69

-

[8]Pozsar, Z. (2014) “ Shadow Banking: The Money View”, Office of Financial Research WP 14-04

-

[9]FSB (2013) Strengthening Oversight and Regulation of Shadow Banking: Policy Framework for Addressing Shadow Banking Risks in Securities Lending and Repos”, August 2013

-

[10]FSB (2014) “Strengthening Oversight and Regulation of Shadow Banking: Regulatory framework for haircuts on non-centrally cleared securities financing transactions”, October 2014

-

[11]FSB (2013), Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2013, 14 November 2013.

-

[12]See Goodhart, C. (2008), “The Boundary problem in financial regulation”, National Institute Economic Review, Vol. 206, No 1, pp 48-55

-

[13]See “Banking union and the future of banking”, speech by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at the IIEA Conference on “the Future of Banking in Europe”, Dublin, 2 December 2013.

-

[14]See also October 2014 IMF Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 2: Shadow banking around the globe: how large, and how risky.