From boom to bust: towards a new equilibrium in bank credit

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, Ernst & Young Business School seminar, Milan, 29 January 2010

1. Introduction [1]

There is now a broad consensus that the period leading up to the crisis was characterised by excessive credit growth. When the bubble burst, it resulted in the most pernicious banking crisis since the Second World War, accompanied by a severe economic recession.

In order to revert to a more balanced and sustainable management of credit, while safeguarding the role that credit plays in stimulating growth, new rules, regulations and incentives for financial market participants are needed. This is what the regulatory authorities and governments of all major industrial countries and developing countries are working towards.

This is not the end of the issue, however. Once the objective of establishing a new “steady state” has been identified, the path towards achieving this objective must be carved out. This will not be easy. If the adjustment is too swift, it could result in an over-adjustment of credit flows, i.e. be too restrictive, giving rise to recessionary effects on the real economy. If the adjustment is too slow, however, it could encourage a return to past behaviour, which led to excessive risk-taking.

Today I would like to examine the issues relating to the role of the banking sector in supplying credit flows, in terms of the following three phases: the pre-crisis state of imbalance, the new long-term steady state, and the period of transition leading up to said steady state.

2. The banking system during the credit boom years

As with all system-wide banking crises, the recent turmoil was preceded by strong credit growth, combined with a speculative asset price bubble. [2] This is confirmed by various credit indicators, such as the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its trend, detrended global credit growth [3], the credit growth gap, and other indicators [4].

For example, the global credit-to-GDP ratio gap, an indicator of the risk of speculative bubbles, had exceeded its threshold in mid-2007. Likewise, the credit growth gap and the investment-to-GDP ratio had been on a strong upward trend, signalling the turmoil to come. Looking at the various market segments confirms the excessive ease with which banking credit had been obtained, for instance, the boom in lending to finance leveraged buyouts (LBOs) [5].

Fast credit growth in the period leading up to the crisis took place against a background of high capital ratios [6]. This was likely driven by four main factors. First, a large share of the credit granted by large banks, in particular, was shifted off-balance sheet via securitisation. Second, non-banks (financial leasing companies, credit card firms, etc.) also contributed to the credit flow. Third, the high profitability of banks contributed to the bolstering of their balance sheets. Finally, most banks, particularly those in the United States, were operating under the Basel I regime. Increasing risks, therefore, were not fully reflected in minimum capital requirements.

The flow of credit, apart from being “excessive”, was in part also channelled to insufficiently productive uses. There was excessive leverage in some sectors, which contributed to the misalignment of underlying asset prices. For example, between 2003 and mid-2007, corporate loans to construction and real estate activities constituted almost 60% of total flows of loans to non-financial corporations in the euro area [7]. The easy flow of credit to the housing sector contributed to the overheating of property markets in some countries. When the crisis set in, the declines in credit were most pronounced in countries such as Spain, Ireland, Belgium and Greece, which had been experiencing double-digit credit growth rates during the lead‑up to the crisis.

Banking credit developments prior to the crisis were excessive owing to a combination of three factors: 1) financial innovation; 2) insufficient supervision, and 3) a highly accommodating monetary policy. Let’s take a quick look at these factors.

The significant advances in financial innovation over the last decade fuelled the idea that asset liquidity had increased and that there was a greater potential for risk diversification. This idea proved, in part, to be an illusion. When the crisis erupted, the presumed liquidity of these assets disappeared. Banks’ balance sheets were thereby clogged by illiquid assets. The growing role of infrastructure for clearing and settling OTC trades – non-standardised and predominantly bilateral – created uncertainty regarding the distribution of exposures among the various counterparties, fuelling their mutual distrust.

Another factor that helped create the perception of greater liquidity was the increased funding available from wholesale financial markets. Moreover, the originate-to-distribute model was adopted not only by large institutions but also by others, such as Northern Rock, which were not equipped to deal with funding sources considerably more volatile than traditional sources, such as deposits.

Recourse to wholesale markets contributed to exacerbating credit pro-cyclicality, with more abundant credit in periods favourable to markets but also greater vulnerability in the case of tighter markets conditions. This problem is not new. The crisis affecting savings and loan undertakings in the United States also originated in the differing maturities of bank assets and liabilities, which gave rise to risky activities in the junk bond and derivatives markets. [8]

Securitisation played a role in creating cheaper and abundant credit, providing banks with additional funding sources. [9]

These developments posed unprecedented and significant challenges for supervisory and regulatory authorities. Although, in some cases, the growing risks and vulnerabilities were identified at the aggregate level, there was insufficient information to understand the interconnections that had been created in the financial system. Furthermore, risk assessments mainly targeted market participants’ behaviour rather than formulating concrete ways to intervene. This reflected the micro-prudential approach of existing legislation, which mainly focused on individual financial institutions, without taking account of interconnections.

Let me also briefly mention monetary policy. A wide-ranging discussion is currently under way about the role that keeping interest rates at low levels for a prolonged period has played in fostering the supply of bank credit. According to some research, there is no correlation between the level of interest rates and bank credit, in particular real estate lending. [10] Other recent studies suggest the opposite, providing evidence of several transmission channels. First, the low level of interest rates may affect valuations, incomes and cash flows, which, in turn, can modify the way in which banks measure the expected risks associated with lending. [11] Second, low returns on comparable so-called risk-free securities, such as government bonds, prompt banks, asset managers and insurance companies to take on more risk and invest in assets offering higher returns, particularly if the performance of managers is measured on the basis of nominal yields. [12] Finally, low interest rates facilitate leverage.

Overall, although, from an empirical standpoint further analysis is needed, it is difficult to reject the view that the policy of low interest rates contributed to the steady credit dynamics in the period preceding the crisis. Certainly, this is a theme that should be studied further in the economic literature in the next few years.

3. The new steady state

Given that the financial crisis has demonstrated the excesses in credit developments in the past, it is necessary to identify a new, sustainable equilibrium point. To reach this steady state, important measures are needed in various areas, many of which are already in process. I will obviously not go into all of them, given the extent of the work in progress, but I will mention a few initiatives.

First of all, the regulation of the banking system must be reviewed, with new rules constraining its assets and balance sheet structure. In December 2009, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision announced a reform package aiming to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations. Capital requirements will be more stringent, thanks to the improved quality, consistency and transparency of the regulatory capital base. Proposals include a counter-cyclical capital buffer, and measures to promote provisioning over the cycle and to mitigate the possible excess cyclicality arising from the minimum capital requirements. [13] Measures concerning the role of external ratings and the treatment of securitisation have also been announced.

Better risk coverage is also needed, which is capable of capturing major on and off-balance sheet risks and derivative-related exposures. Various proposals have been formulated in this regard, including: strengthening the capital requirements for counterparty credit risk exposures arising from derivatives, repos and securities financing activities; a leverage requirement (capital divided by total exposure) to put a cap on the level of leverage in the banking sector; and internationally harmonised global liquidity standards, including a liquidity coverage ratio and a structural ratio (measuring the amount of longer-term stable funding sources to cover the liquidity needs for funding assets over the period of one year). Finally, governance of financial institutions must be strengthened, for instance with regard to remuneration incentives. [14]

The regulatory community is well aware of the fact that the reform must be introduced in an ordered manner in order to ensure the resilience of the financial system as a whole, while also supporting economic growth over the longer term. The proposals are currently the subject of extensive consultations with the banking system. In addition, an impact study will be conducted to assess the implications of the various measures. Based on the outcome thereof, the aim is to arrive, by the end of 2010, at an appropriate calibration for the new requirements in terms of the level and quality of capital, in order to find a balance between financial innovation, financial stability and sustainable economic growth. The Basel reform will be phased in gradually as financial conditions improve and the economic recovery strengthens, with the aim of implementation by the end of 2012. Appropriate grandfathering arrangements will be put in place in order to ensure a smooth transition.

A further point highlighted by the crisis is the availability of resolution schemes that allow for speedy and decisive interventions in the event of bank failures or near-failures, averting deposit runs and limiting contagion effects on the wider banking system. Several initiatives in this area are under way both at the European and global levels. [15]

As regards derivatives, the aim is to increase transparency and risk management, especially through the creation of market infrastructures to centralise transaction settlement.

Another area in which more stringent requirements are to be imposed is that of securitisation and credit derivatives activity. [16] During the crisis, there was a strong decrease in securitisation. For this segment of the market to experience a broad recovery, fundamental changes towards more transparency, standardisation and simplicity are required. There are various initiatives, both public and private, targeting this. The ECB is taking measures in order to gradually align the collateral eligibility criteria and risk control measures with best market standards and investors’ requirements. [17]

In the context of the regulatory reform, the international community has committed itself to reducing the moral hazard posed by systemically important financial institutions. A number of proposals are being discussed with international bodies, in particular the Basel Committee and the Financial Stability Board. The debate recently gained momentum following the President of the United States’ proposal to adopt the “Volcker rule”, which aims to separate the activities of large financial institutions. An important element of this proposal is that any financial institution that obtains federally-insured deposits or has access to refinancing from the Federal Reserve would be prohibited from owning, investing in or sponsoring hedge funds or private equity firms. Essentially, it aims to separate traditional banking activities from higher-risk, proprietary trading operations. It also proposes imposing limits on large financial institutions regarding their market share of liabilities, as a supplement to the existing caps on the market share of deposits.

These proposals have still not been detailed in depth. Nonetheless, on the basis of what has been made public, I am of the view that the initiative is heading in the right direction and represents the first step to ensuring the financial system can effectively support the real economy and is not weakened by the most volatile market fluctuations. It is, however, not the final step. Above all, it should not be a substitute for two other lines of action, which, in my opinion, are essential for a complete reform of the system. The first is that the whole financial system should be subject to regulation, even if the specific regulations may vary according to the activities or institutions to which they apply. However, I do not want the separation between traditional banking activities and high-risk proprietary trading operations to drive the latter to be undertaken by sectors or institutions that are less vigilant or are outside the sphere of regulation. My concerns arise from the fact that, while during the first G20 summit meetings, there was widespread consensus on the necessity of ensuring that no segments of the financial system are left outside the scope of the regulatory framework, over time, this resolve has dwindled and attention has mainly been focused on banks. Given the interconnectedness of markets, it is essential that investment banks, hedge funds and other institutions are also subject to adequate regulation. In particular, the supervisory authorities must have adequate information on the activities of these institutions in order to be able to evaluate vulnerabilities and possible contagion effects. The second line of action relates to the strengthening of the supervisory authorities, beginning with their independence. Only institutions independent not only of political authorities but also of market participants can have the clarity and the power to take measures to reduce the cyclicality of credit and financial activities. There are, therefore, concerns regarding the developments in the current debate in the United States, where the most independent institution, namely the Federal Reserve, is subject to attacks and pressures from various corners, including legislative initiatives aiming to curtail its powers.

A final concern regarding international cooperation is this: there is no doubt that the “Volker rule” represents a new topic for discussion and that there is a risk that not all countries will want to follow this path, out of a wish not to penalise the financial institutions based in their own countries through the new regulations on separation. As has been the case in the past, it can be expected that vast financial resources will be employed in an attempt to influence political decisions and to stand in the way of a proposal of this kind. It would be a shame if the authorities in major countries put the interests of these institutions ahead of those of the taxpayers and ahead of global interests.

This brings me to the role that central banks can play in supporting more sustainable credit flows. Recent work shows that price stability is necessary, but not sufficient to ensure a homogenous flow of credit to the economy and avoid financial instability. In particular, if monetary policy concentrates solely on inflation objectives, it might, in some circumstances, end up being too accommodative of credit cycles and fuel speculative bubbles. Such a risk tends to become more apparent when interest rates are kept at a very low level for an extended period of time.

On the other hand, it appears to be a difficult task for a central bank to use one instrument, such as interest rates, to achieve two objectives at the same time, namely price stability and financial stability. This is the reason why central banks should also be equipped with macro-prudential instruments, distinct from monetary policy, which can be used in order to avoid the excessive pro-cyclicality of credit. These instruments should enhance the stability and resilience of the banking sector over the business cycle, as well as the sustainability of the balance sheet structures of borrowers. A more efficient allocation of credit should result, thus helping to avoid the build-up of financial imbalances and contributing to improved economic performance.

To sum up this part, the new steady state will be characterised by higher capital ratios and lower leverage in the banking sector, and probably also less recourse by the banking system to market financing in general, and to securitisation in particular. This will allow for more stable credit growth, which is less subject to pro-cyclicality, especially that deriving from supply factors. Credit growth will also be less affected by financial market volatility. [18]

4. The transition

The transition from the old equilibrium, which was really one of imbalance, to a new, more sustainable one cannot be instant, as that would involve an excessive adjustment with potentially recessionary effects. Nor can it take too long as this would risk creating incentives to return to the unsatisfactory behaviour exhibited prior to the crisis. Defining the transition phases is possibly the most difficult challenge.

The transition is characterised not only by the lag between decisions relating to new prudential regulations and their application, of which I spoke earlier, but also by the extraordinary measures in terms of monetary and financial policy, adopted by governments and central banks to combat the recession and support the financial system in facing the systemic crisis.

The major central banks have promptly and forcefully responded to the crisis with a broad variety of measures. The classical prescription by Walter Bagehot, which describes central banks as lenders of last resort, has proven to be as valid today as it was 137 years ago when “Lombard Street” was first published. [19] Accommodating the sudden increase in the demand for liquidity prevented a disorderly de-leveraging process, prevented illiquid but solvent banks from going bust, and, more broadly, sustained confidence in the economy.

The steps taken by central banks have taken them into, up to now, uncharted territory. Interest rates have been reduced to very low levels by historical standards, clearing the way for significantly lower bank interest rates (although with a significant time-lag), thus supporting credit demand from households and firms. At the same time, non-conventional measures have been adopted with the aim of bringing abnormally high money market spreads down and ensuring a proper transmission of the monetary policy impulse.

These exceptional measures have had important effects on macroeconomic and financial stability, and improved the overall conditions on financial markets. [20] In particular, they have helped to “liquefy” assets that could otherwise have caused the insolvency of many financial institutions. More generally, they have helped to restore confidence by reducing uncertainty. In addition, they have prevented contagion effects that can arise in the financial system as a result of the inter-connectedness between various market participants.

The monetary policy intervention also helped to restore the profitability of banks as the fall in short-term interest rates steepened the yield curve, to the benefit of the banking system, which usually funds itself in the short term in order to provide credit for longer terms. This profitability also helped to support the flow of credit to the economy.

Financial measures have also been adopted, such as increased deposit insurance, guarantees for bank liabilities, and injections of capital. In addition, fiscal budgets have supported aggregate demand via automatic stabilisers and expansionary measures.

Over the last few months, leverage has generally fallen, especially among those institutions that were most highly leveraged. [21] The fall reflects, in part, recapitalisation efforts, lower risk-taking as a result of more prudent lending standards, and the shedding of assets and/or limitation of the growth in balance sheets. It also reflects pressure from the market and supervisory authorities to control leverage, as well as expectations regarding the possible introduction of a leverage ratio, in addition to risk-based capital requirements. [22], [23]

Likewise, capital position ratios of large and complex banking groups in the euro area are improving. The earnings of these banks have recovered, while the growth of total assets and of risk-weighted assets has slowed down and capital has increased, both from public and private sources. These developments were necessary in view of the expected increase in non-performing loans as a delayed result of the economic crisis.

With improving conditions in the economy and financial markets, supportive measures by governments and central banks have progressively less “raison d’être”. The withdrawal of these measures must occur in a timely fashion; being too early or too late could have unwanted implications for the speed at which the new steady state can be reached. In particular, too brisk a phasing-out could lead to a dramatic process of de-leveraging, jeopardising the economic recovery. On the other hand, it is essential to prevent the banking system from relying on support measures for too long, i.e. becoming “addicted” to them. The intermediation role of the central banks during the crisis, if drawn out for too long, may reduce incentives for banks to return to actively operating in the money market. Such a scenario may also weaken incentives to restructure banks’ balance sheets.

Credit flows to households and firms represent an indicator of financing conditions and of the prospects of a recovery in economic activity. However, they also reflect supply and demand factors. On the whole, developments in credit appear to have been, up to now, in line with historical regularities, according to which loans to firms typically lag the economic cycle by a couple of quarters. In fact, credit flows remained positive, even during the period of the most severe contraction in economic activity, presumably as a result of the growing use of credit lines and revolving credit facilities. [24] Therefore, lending to firms can be expected to remain subdued even in the early stages of economic recovery, but it cannot be ruled out that supply factors will continue to restrict credit for some months. [25] The flow of loans to households began to grow again at the end of last year.

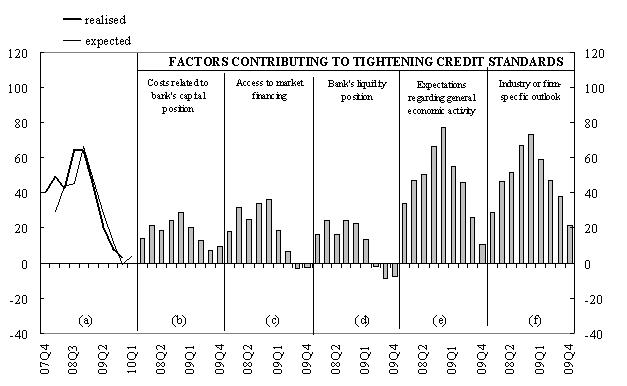

The quarterly survey on bank lending indicates that the degree of tightening adopted by banks for the granting of credit to firms declined over the last few months of 2009, but remain positive (see Figure 1). It is interesting to note that among the factors that affect banks’ restrictive intentions, neither the one concerning the liquidity position of the banks themselves nor the one concerning access to financial markets seems significant any longer. Both factors now contribute in a positive way to the intentions of banks to grant credit. Considerations relating to the prospects for economic growth and those linked to specific sectors of the economy remain restrictive, but the degree of restriction is declining sharply. The element that marks a growing concern with regard to restrictiveness relates to the capital of banks. Clearly, the considerations in respect of the need to replenish capital are starting to exert a strong influence on the decisions of banks to grant new credit.

This dynamic is worrying. It indicates that the banking system is interpreting the new regulations restrictively for credit. This approach is undesirable and out of line with the objectives so far followed by the economic policy authorities of supporting the financial system, not as an end in itself but as an essential function of savings intermediation. The outcry surrounding the effects that future capital standards and risk management – the so-called “Basel 3” – will have on credit developments in the short term seems unjustified. The new rules are specifically intended to ensure a more orderly and sustainable flow of credit, not a reduction. Moreover, as I said earlier, a gradual process of adaptation to the new requirements is foreseen.

The new capital requirements may be attained in two different ways, although they have opposite effects on banking activities: reduction in banking activities, particularly in credit to firms, on the one hand, and capital increase on the other. The alarm that seems to be widespread in the banking sector concerning the new rules seems to mask the intention of adapting to them via a reduced exposure to the real economy, rather than via a capital increase. This reaction seems to reflect the incentive of managers and shareholders to favour remuneration on equity and human capital, rather than long-term investment. This is not in line with the macroeconomic objectives. This is why we insist that the profits made in these months by the banking sector – which were obtained thanks to the interventions by the policy authorities to keep the system going, and thus ultimately by the taxpayers – should be used to increase the capital rather than to reward the banks’ managers and shareholders. This applies not only to banks that have received direct assistance through guarantees and public capital injections, but also to the indirect benefits obtained as a result of low interest rates.

5. Conclusion

The pre-crisis period was marked by unsustainable credit policies by the banks and, more generally, by the financial system. These policies were encouraged by inadequate supervision and slack prudential regulation, and also by the excessive influence the financial system had on regulatory mechanisms. This caused the biggest crisis of the post-war period.

We must find a new equilibrium in which the financial system truly supports the real economy, encouraging a flow of balanced credit. The adjustment may not be immediate and it needs to follow a gradual path in order to arrive, in due course, at a new point of balance that allows a restoration of confidence not only among investors but also taxpayers. Everyone must play his or her part. The regulatory authorities have to agree quickly on the new system parameters, in consultation with the private sector. Macroeconomic policy must promote conditions for a gradual adjustment, in line with the objective of sustaining economic growth and the restoration of a financial market that efficiently performs its primary role as an intermediary. Market players must understand that the future cannot be a simple return to the past, to the pre-crisis situation.

If we fail to reach the new equilibrium in due course we will have wasted not only the crisis but also the resources of taxpayers that have been used to save the system. This can only backfire on the system.

Figure 1

| Changes in credit standards applied to the approval of loans or credit lines to enterprises(net percentages of banks contributing to tightening standards) |

|

| Notes: The net percentage refers to the difference between the sum of the percentages for “tightened considerably” and “tightened somewhat” and the sum of the percentages for “eased somewhat” and “eased considerably”. The net percentages for the questions related to the factors are defined as the difference between the percentage of banks reporting that the given factor contributed to a tightening and to an easing. |

-

[1]I would like to thank, in particular, L. Cappiello, P. Aberg, G. Wolswijk and D. Marqués Ibañez for their contribution to the drafting of this speech. The opinions expressed are solely my own.

-

[2]See C. Borio and P. Lowe, “Securing sustainable price stability: should credit come back from the wilderness?”, BIS Working Paper, No 157, Bank for International Settlements, 2004; C. Borio and M. Drehmann, “Assessing the risk of banking crises – revisited”, BIS Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, 2009.

-

[3]See L. Alessi and C. Detken, “Real time early warning indicators for costly asset price boom/bust cycles: a role for global liquidity”, ECB Working Paper Series, No 1039, 2009. According to these authors, a global credit-to-GDP ratio gap is one of the best indicators (with a lead-time between six quarters and three years) for asset price bubbles that are followed by busts, which prove costly in terms of GDP losses.

-

[4]See D. Gerdesmeier, H.-E. Reimers and B. Roffia, “Asset price misalignments and the role of money and credit”, ECB Working Paper Series, No 1068. The authors find that the credit growth gap, the investment-to-GDP ratio, the variations in the long-term interest rate and the house price/equity price gaps can signal asset price busts that are likely to occur in the next two years.

-

[5]Syndicated loans extended to finance LBOs in the euro area reached an annual sum of almost €140 billion around mid-2007, and in the 2005-07 period loans to finance LBOs constituted around 13% of the total syndicated loan market compared with around 6% both before and after the boom years, based on data from Dealogic.

-

[6]The Tier 1 ratio fluctuated around 8% and the total capital ratio around 11%. See the ECB’s Financial Stability Review, December 2007.

-

[7]See also the box entitled “Developments in MFI loans to non-financial corporations by industry” in the December 2009 issue of the Monthly Bulletin.

-

[8]Eventually, this required a clean-up programme with an estimated cost of USD 150 billion.

-

[9]See, for example, A. Ashcraft and T. Schuermann,

-

[10]Ben Bernanke, “Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble”, a speech delivered at the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, Atlanta, Georgia, 3 January 2010.

-

[11]T. Adrian and H.S. Shin, “Money, liquidity and monetary policy”, American Economic Review, P&P, vol. 99, No 2, pp. 600-605, 2009; J.B. Taylor, “The financial crisis and the policy responses: an empirical analysis of what went wrong”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No 14631, 2009.

-

[12]M.K. Brunnermeier, “Asset pricing under asymmetric information - bubbles, crashes, technical analysis and herding”, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001; R.G. Rajan, “Has financial development made the world riskier?”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No 11728, 2005; G. Jiménez, S. Ongena, J.-L. Peydro and J. Saurina, “ Hazardous times for monetary policy: what do 23 million loans say about the impact of monetary policy on credit risk?”, CEPR Discussion Paper, No 6514, 2007; V. Ioannidou, S. Ongena and J.-L. Peydro, “ Monetary policy, risk-taking and pricing: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment”, NBER Summer Institute, 2009; A. Maddaloni and J.-L. Peydro, “Bank risk-taking, securitisation, supervision and low interest rates: evidence from lending standards”, ECB Working Paper Series, forthcoming.

-

[13]The potential role of capital regulation (Basel II) in amplifying credit cycles is being investigated by a number of authorities and institutions, including the Basel Committee and the ECB. The consultative document issued by the Basel Committee on 17 December 2009 already includes proposals on: (i) mitigating the cyclicality of the minimum requirement; (ii) introducing forward-looking provisioning; (iii) building buffers through capital conservation; and (iv) mitigating excessive credit growth. The latter would imply the introduction of a counter-cyclical buffer requirement, which would come into effect during periods of excessive credit growth. The Basel Committee’s proposal is currently at an early stage of development and a fully-fledged version will be developed by the Committee in time for its June 2010 meeting.

-

[14] See, for instance, F. Panetta and P. Angelini (coordinators), U. Albertazzi, F. Colomba, W. Cornacchia, A. Di Cesare, A. Pilati, C. Salleo and G. Santini, “Financial sector pro-cyclicality – lessons from the crisis”, Questioni di Economia e Finanza, No 44, Banca d’Italia, 2009.

-

[15]At the international level, the Basel Committee’s Cross-border Bank Resolution Group has published a report with recommendations to improve the resolution of failing financial institutions that conduct cross-border activities. At the European level, the European Commission has launched a public consultation on the EU framework for cross-border crisis management in the banking sector.

-

[16]See, for instance, the Basel Committee of Banking Supervision, “Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector”, December 2009.

-

[17]For example, in September 2008 the ECB announced higher transparency requirements, including the need for regular surveillance reports by rating agencies. In early 2009 it increased the rating requirement for newly issued ABSs to AAA at issuance and discontinued the acceptance of double-layer securitisations. In November 2009 it announced the eligibility requirement that, as of 1 March 2010, at least two ratings must comply with the minimum rating threshold applicable to ABSs. Moreover, on 23 December 2009 the ECB launched a public consultation on the establishment of loan-by-loan information requirements for ABSs in the Eurosystem collateral framework.

-

[18]In fact, recent studies have shown that securitisation and credit derivatives tend to increase the supply of bank loans; see, for instance, Estrella, “Securitisation and the efficacy of monetary policy”, Economic Policy Review , vol. 8(1), Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2002; Hirtle, “Credit derivatives and bank credit supply”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report, n. 276, 2007; Y. Altunbas, L. Gambacorta, D. Marques-Ibanez , “Securitisation and the bank lending channel”, European Economic Review, Vol. 53, Issue 8, 2009.

-

[19]W. Bagehot, “Lombard Street: a description of the money market”, Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1873.

-

[20]With regard to the importance of an accommodative monetary stance at the margin, see, for instance, T. Adrian and H.S. Shin, “Financial intermediaries and monetary economics”, Handbook of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

-

[21]It should be noted that this effect only arises when the impact of losses on the capital base is greater than the reduction in the value of marked-to-market assets on the balance sheet.

-

[22]There are currently three countries that use, or plan to use, a leverage ratio, namely the United States, Canada and Switzerland. Switzerland has introduced a leverage ratio for its two large, internationally active banks, which will take effect in 2013.

-

[23]Pressure on banks to reduce leverage has been apparent from discussions in various international fora, such as the G20, which has called for the introduction of leverage ratios, in addition to risk-based capital ratios, in order to prevent banks from arbitraging capital requirements.

-

[24]Indeed, in the context of the recent turmoil, while the annual growth in undrawn credit lines, following an increase up to mid-July 2007, has been on a declining trend and moved into negative territory in the course of 2008, the annual growth in the draw-downs of credit lines has been increasing up to the third quarter of 2008.

-

[25]This is based on information derived from the Eurosystem’s Bank Lending Survey.

Europos Centrinis Bankas

Komunikacijos generalinis direktoratas

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurtas prie Maino, Vokietija

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Leidžiama perspausdinti, jei nurodomas šaltinis.

Kontaktai žiniasklaidai