Assessment of quantitative easing and challenges of policy normalisation

Speech by Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at The ECB and Its Watchers XIX Conference, Frankfurt am Main, 14 March 2018

The financial crisis that erupted in 2008 posed unprecedented challenges for central banks across the world in the pursuit of their statutory mandates. [1] A main feature of central banks’ response to the crisis was the deployment of additional, and in some cases novel, monetary policy instruments. One of these instruments was what’s known as “quantitative easing”. In the case of the euro area, this tool has not been used in isolation, but rather as part of a comprehensive package of complementary measures taken to combat the disinflationary forces that intensified in mid-2014.

Today I will first look at the impact of our policies on financial conditions and macroeconomic variables. The correct measure of the efficacy of unconventional monetary policy measures has been the subject of some debate in recent times. In particular, the durability of the imprint that such unconventional policies have left on financial conditions has been called into question. Overall, diverse empirical approaches to quantifying the impact of our package of measures support the same conclusion: the actions we took have had a strong and lasting effect on market conditions, and more importantly, achieved a potent pattern of propagation to the broad economy. We cannot yet declare “mission accomplished” on the inflation front, but we have made substantial progress on the path towards a sustained adjustment in inflation.

I will then turn to the key challenge we face as we move towards normalisation. For several years net asset purchases have been the primary instrument for calibrating our monetary policy stance. Looking forward, once the Governing Council has assessed that the criteria have been met for a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation, the challenge will be to pivot to a more normal situation where interest rates and guidance on their likely evolution will once again become the primary instrument for adjusting our stance, while ensuring that financial conditions remain supportive of inflation convergence towards levels of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

The impact of the ECB’s non-standard measures

By mid-2014, the euro area economy was facing disinflationary pressures that risked spiralling into outright deflation. With the deposit facility rate held at zero since July 2012, our ability to provide the necessary degree of monetary stimulus using conventional policy measures was very limited.

Under these conditions, the focus of providing monetary accommodation shifted from an approach based on adjusting the interest rate corridor of our monetary policy framework – which steers the very short end of the yield curve – to one that more directly affects the whole constellation of interest rates across the yield curve. Specifically, the instruments we have employed since June 2014 are negative interest rates on the deposit facility, which provide the floor of the corridor; a reinforced form of forward guidance on the evolution of the interest rate corridor in the future; targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs); and the asset purchase programme (APP).

With policy rates at exceptionally low levels, the APP soon became the primary instrument for calibrating the monetary policy stance. How effective have our asset purchases been in helping the ECB to accomplish its statutory objective in the medium term? Answering this question is inherently difficult because of the complex interaction of our APP with other policy instruments as well as our evolutionary communication about the purchase programme, through which we signalled our intention to start buying bonds and, later, to recalibrate the size and duration of our bond-buying programme in advance. Hence, in assessing the impact of the APP, we must also take into account the other policy tools used since mid-2014, because the instruments were designed to be complementary and mutually reinforcing.

The four instruments that have determined the stance of our monetary policy since mid-2014 have been designed to reap the full benefits of their complementarities. Two examples highlight the role played by complementarities in policy design. First, the negative interest rate policy has supported the portfolio rebalancing channel of our APP by encouraging banks to lend to the broad economy instead of hoarding liquidity.[2] Second, the APP has supported rate forward guidance via the signalling channel. Generally, asset purchases are thought to provide a strong signal that policy rates will remain low for an extended period of time. For the ECB, this effect is reinforced by the sequencing of our instruments through which we have indicated that our policy rates will likely remain at their current levels “well past the horizon of our net asset purchases”.

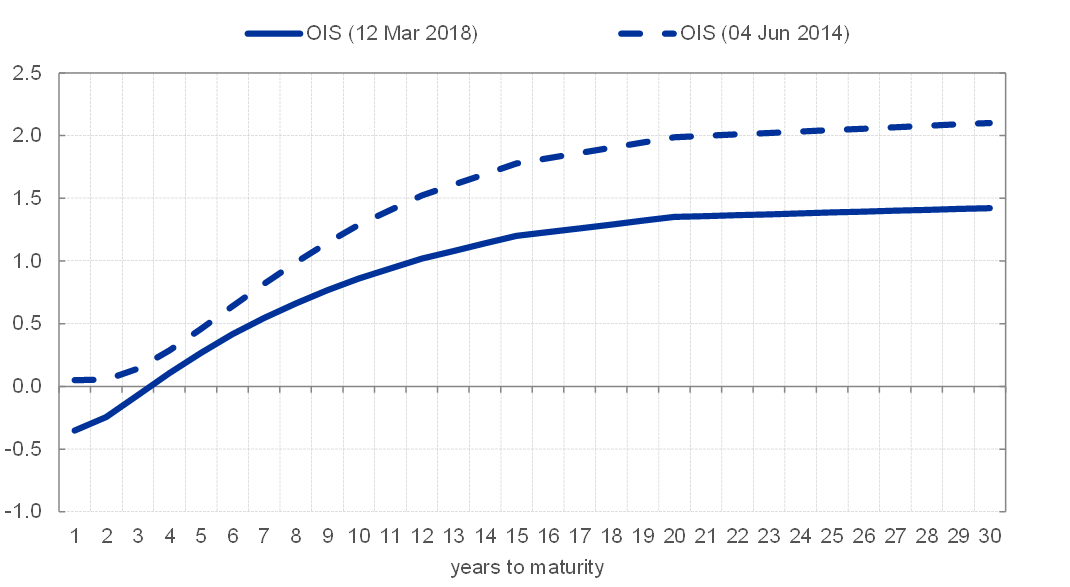

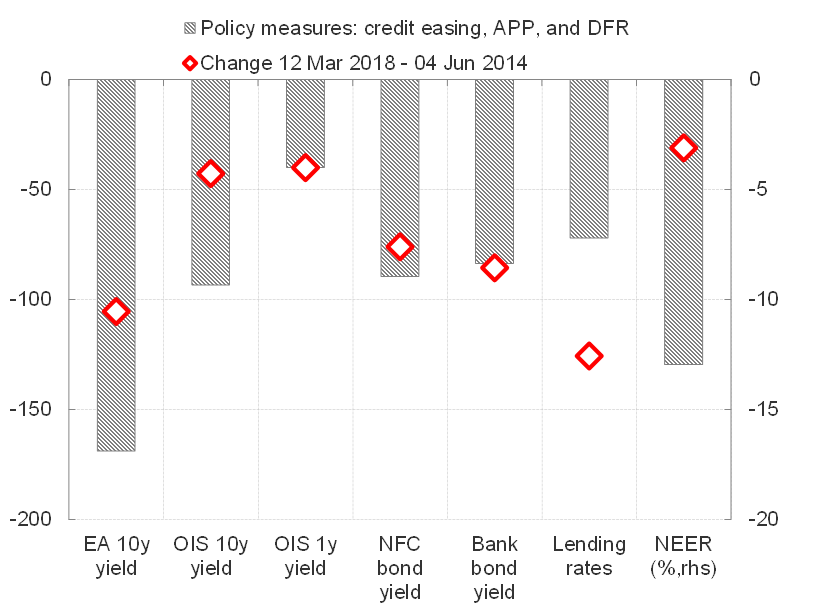

Our overall assessment – and that of a growing body of empirical literature – is that non-standard measures have had a sizeable and lasting impact on broad financing conditions [Chart 1].[3] These improvements are not limited to the asset classes included in our APP, but have spilled over to other market segments [Chart 2]. In addition, easier market funding conditions have been passed through to bank lending rates.[4] Importantly, these findings are based on a range of econometric techniques and are therefore robust to the limitations associated with any individual methodology.

Chart 1: Term structure of interest rates (percentages per annum)

Sources: Bloomberg, ECB, ECB calculations. Latest observation: 7 March 2018.

Chart 2: Impact of ECB measures on key financing conditions (contributions in basis points and percent)

Sources: ECB, ECB calculations.[5]

Event studies – which measure the impact of central banks’ bond purchases in a narrow interval around the time of the announcement – play a part in informing our view on the efficacy of our purchases. But we also use model counterfactuals to complement the impact metrics that we derive from event studies, and to test whether or not the impact of our announcements endures beyond the very short term. In this context, dynamic term structure models of the type that have become standard in contemporary fixed income finance, augmented with a factor capturing central bank bond holdings, have consistently confirmed the inference we draw from event studies. They indicate that our purchases have had a sizeable and durable influence on long-term yields.[6]

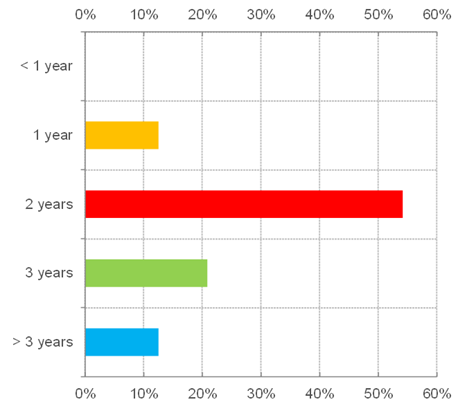

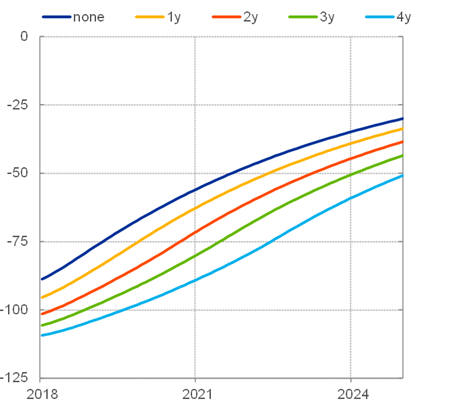

At present, the current and anticipated size of our APP portfolio – which has been increased in various recalibration steps and is expected to be maintained “for an extended period of time” after the end of net asset purchases – is still putting downward pressure on euro area long-term yields. The longer the expected period of reinvestment, the stronger the downward pressure on yields. If one takes current surveys of market participants’ views about the time over which the ECB is anticipated to roll over its APP securities, and assumes the modal expectation of a two-year period, one finds that the downward pressure that APP asset holdings – current and expected – are exerting on longer-term interest rates is in the order of 100 basis points [Chart 3].

Chart 3: Reinvestments as an ongoing source of monetary policy support

Panel A: Expected reinvestment horizon after net asset purchases (percent of respondents)

Source: Bloomberg (2 March 2018). Note: Answers to the question “How Long for Reinvestments After End of Asset Purchases”. 48 respondents.

Panel B: Estimated effect on euro area ten-year term premium of APP for different reinvestment scenarios (basis points)

Source: Eser, Lemke, Nyholm, Radde, and Vladu (mimeo).[7]

Downward pressure on yields is expected to be very persistent and to decline only gradually, but consistently, as we move forward in time, because of what is referred to as the “portfolio ageing” effect. The effects of our purchases of long-dated assets on market yields are principally due to the fact that we withdraw duration from private hands, and as the securities we hold in our portfolio draw closer to maturity and “lose duration” progressively, the overall amount of duration contained in our portfolio has a tendency to melt away. And this gradual loss of duration will reduce downward pressure on yields [Chart 3].[8]

There has been a strong pass-through of our non-standard measures to financing conditions. For example, model-based counterfactual simulations attribute more than half of the 126 basis point decline in lending rates to non-financial corporations since June 2014 directly to our non-standard measures [Chart 2]. The APP has supported the provision of loans to customers at better terms and conditions.[9] Banks themselves – when asked to assess the effects of our measures on their intermediation business – have reported that the APP has positively impacted their market financing conditions.

As a consequence of this generalised easing in financing conditions, our measures have had substantial macroeconomic effects. Taking into account all of the monetary policy measures taken between mid-2014 and October 2017, the overall impact on euro area growth and inflation is estimated, in both cases, to be around 1.9 percentage points in cumulative terms for the period between 2016 and 2020.

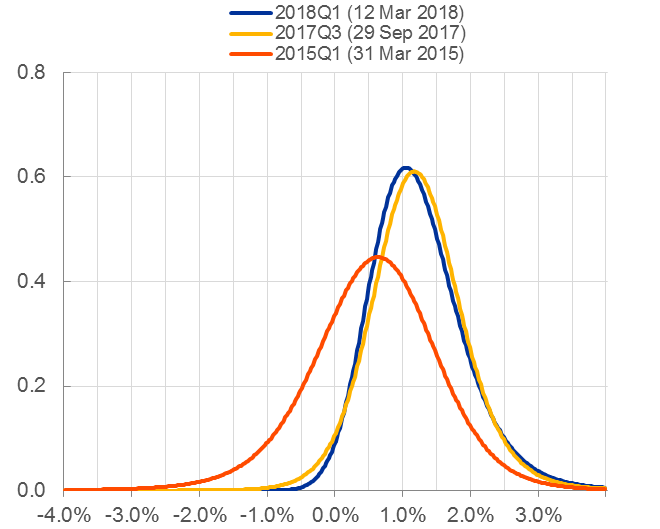

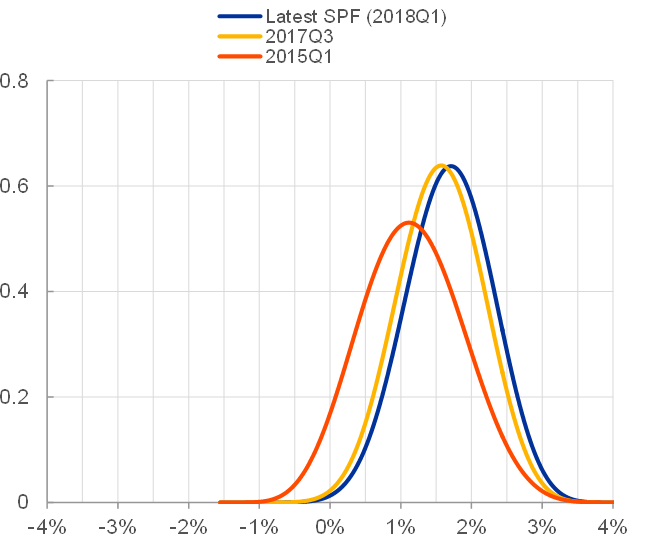

To sum up, the available evidence strongly supports the conclusion that the APP – together with our other non-standard measures – has been effective and probably decisive in warding off troublesome macroeconomic outcomes. It has certainly propelled the economic recovery into a robust and broad-based expansion. And very likely, it has prevented the disinflationary pressures of 2014 from spiralling into a self-reinforcing deflationary vortex [Chart 4]. We cannot yet declare “mission accomplished” on the inflation front, but we have made substantial progress on the path towards a sustained adjustment in inflation.

Chart 4: Probability density functions (PDF) of euro area inflation

Panel A: Option-implied PDF of euro area inflation over the next two years

Sources: Bloomberg, Reuters, ECB calculations.[10]

Panel B: Survey-implied PDF of euro area inflation in two years’ time

Source: ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters.

The conduct of our monetary policy

Our monetary policy reaction function has always been firmly anchored to our objective to maintain inflation at levels below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. Our monetary policy has therefore evolved in line with the outlook for price stability and in a consistent manner over time.

The unprecedented challenges we faced in the pursuit of our price stability mandate led us to introduce a complex and multi-dimensional monetary policy package. The transmission of unconventional instruments to financial conditions, and, further down the road, to economic activity and price developments, is surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty. This begs the question: how should monetary policy be conducted in such an environment?

Over the past 50 years, a number of economists working in both academia and central banks have argued for a gradual adjustment in the monetary policy stance as an optimal approach to policy conduct in a world of uncertainty. Following the seminal work of Brainard,[11] a case for gradualism can be made in the context of the uncertainty inherent in economic data, models and parameters, notably in times of unconventional monetary policy. In the absence of perfect or complete knowledge about the way market participants will react to the announcement of monetary policy adjustments, and about the way those uncertain reactions will transmit to our objective, it may be optimal to adjust policy more cautiously and in smaller steps than if we had perfect knowledge.

More generally, the policy calibration exercise should not be viewed as one in which the central bank decides on the speed at which it should approach a given target level for its instrument or instruments, but rather as an iterative and interactive process where the central bank learns from the markets as much as the markets learn from the implementation of the central bank’s policies.

It is through this feedback loop that central banks and markets alike learn about the nature and strength of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. In that process, a change in the instrument(s) has an impact that is uncertain ex ante in respect of the induced adjustments in the yield curve and other financial prices and, as a consequence, in respect of the likelihood of achieving the objective. Market adjustments are not known until they are observed, and we can only work out what their implications might be for the achievement of our objective once they have materialised.

In these conditions, the Brainard rationale for gradualism applies with great force: do it as carefully and prudently as possible, at least when you have good reason to believe that the degree of uncertainty as to the direction and size of market reactions is atypically large. Present times, where policy is defined by a multiplicity of instruments that interact in ways that are very imperfectly known, are characterised by an abnormal amount of uncertainty.

Gradualism is not a doctrine, but a pragmatic approach that is generally suitable to situations characterised by significant uncertainty about the impact of available policy instruments. A more aggressive monetary policy response, however, is warranted when there is clear evidence of heightened risks to price stability, i.e. when it is established that the degree of inflation persistence is likely to be high and risks disanchoring inflation expectations. In this case, a forceful, frontloaded monetary policy response to weak or excess inflation may become necessary to signal the central bank’s commitment to its objective, and thus nudge inflation expectations towards that objective and make them less backward-looking.[12]

For example, when confronted with the risk of a disanchoring of inflation expectations and a too prolonged period of low inflation, the Governing Council stated in May 2014 that it would “act swiftly” and was “unanimous in its commitment to using also unconventional instruments within its mandate” as needed. This was followed a month later by the announcement of the battery of non-standard measures I already mentioned. In addition, in late 2015, we signalled our determination to bring inflation back to our policy aim “without undue delay”, which justified an aggressive recalibration of stimulus at that time.

Let me now turn to some concrete examples of a gradual approach. Our APP has evolved gradually, subject to its “sustained adjustment” conditionality, i.e. the Governing Council’s intention to continue its net asset purchases until it sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with its inflation aim. The purchase universe was first expanded beyond asset-backed securities and covered bonds to include public and corporate sector securities. Over time, we also extended the purchase horizon and adjusted the monthly purchase volumes to fine-tune the programme in line with our assessment of progress towards a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with our inflation aim.

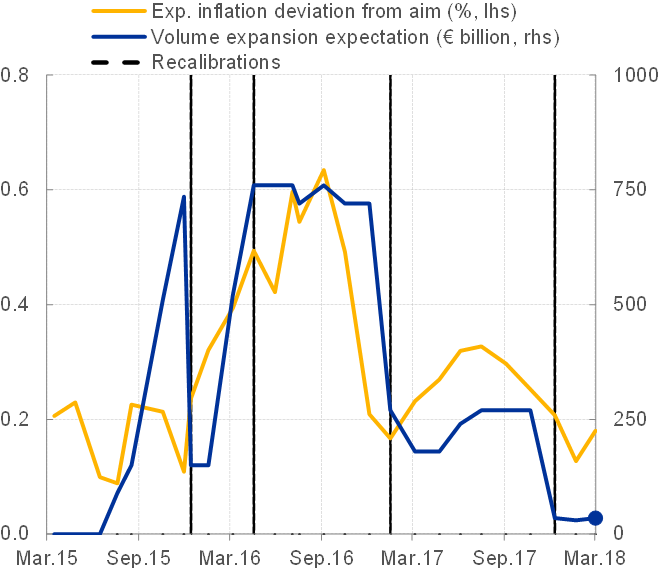

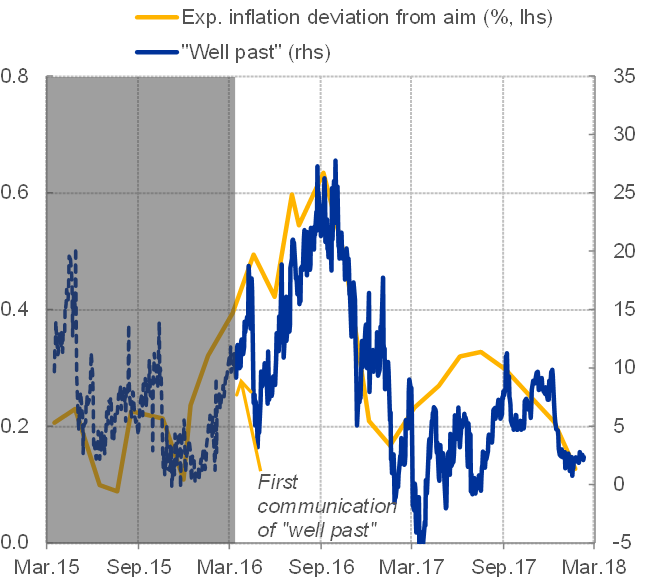

Market expectations have internalised the conditionality framework that governs the size and duration of the APP quite well. Data show that market expectations of our policy are highly correlated with the outlook for inflation, as for example captured by medium-term inflation expectations. This applies both to expectations regarding the horizon and volumes of the APP and to expectations relating to our “well past” guidance on policy rates [Chart 5]. Looking at survey medians, the residual difference between market expectations regarding the size and horizon of our net asset purchases and the indications about the size and horizon of the programme announced by the ECB is today very small. In periods of persistent disinflation, this difference was very large. The convergence of market expectations towards the ECB’s indications about the size and horizon of net asset purchases has proceeded in tandem with the gradual rise of inflation expectations towards our medium-term policy aim. Likewise, there is a strong co-movement between markets’ views of the convergence of inflation towards the ECB’s aim on the one hand and, on the other, the length of the interval between the end of net asset purchases and the first rate rise fully priced into market rates. This suggests that our monetary policy reaction function is well understood.

Chart 5: Correlation between market expectations of monetary policy and medium-term inflation expectations

Panel A: APP extension expectations and inflation undershoots (left axis: %; right axis: €bn)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB.[13]

Panel B: “Well past” horizon implied by expected APP end and forward curve (months)

Source: Bloomberg, ECB calculations.[14]

Sustained adjustment and beyond

Last week, we introduced a further gradual adjustment to our monetary policy stance, removing from our official communication the so-called APP easing bias, i.e. a sentence in which – since December 2016 – we had expressed our readiness to increase the monthly pace and/or extend the horizon of our net asset purchases if certain unfavourable macroeconomic or financial conditions materialised. This step followed earlier adjustments to our policy stance, namely reductions in the pace of purchases and the removal of the easing bias on policy rates. This decision conveys our improving confidence that the strong and broad-based cyclical momentum will eventually lead to a convergence of inflation towards our aim.

Overall, however, it is fair to say that we are still some way short of achieving full and durable convergence of medium-term inflation towards levels below, but close to, 2%. The Governing Council has three criteria for assessing whether there is a sustained adjustment: first, the convergence of headline inflation to our medium-term aim; second, confidence in the realisation of the expected inflation path; and third, the resilience of inflation convergence even after the end of our net asset purchases.

Signals showing the convergence of inflation towards our aim are increasingly positive and we are becoming more confident that inflation will reach a level of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. Nevertheless, from today’s perspective domestic inflation pressures are still subdued and a substantial degree of monetary accommodation remains necessary for price pressures to build up and for inflation to converge sustainably towards our aim.

We must be patient, persistent and prudent with our policy. Patience is needed because it takes time for underlying inflation dynamics to gain momentum and support a durable convergence of inflation towards our aim. Persistence is needed because the recovery in inflation is predicated on a substantial degree of monetary policy accommodation. And prudence is essential because of uncertainties about the transmission of unconventional monetary policy measures on the way to normalisation.

This leads me to the question of how monetary policy will evolve once the Governing Council judges that the criteria for a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation have been met. The answer to this question is essentially already indicated in our forward guidance and in the clear sequencing of policy measures that we have communicated.

Once the Governing Council judges that the criteria for a sustained adjustment have been met, our net asset purchases will end. Only one of the instruments that are currently contributing to the economic expansion and to inflation convergence will then expire. The monetary support that will still be necessary to accompany inflation along the path towards a durable convergence will continue to be provided by the remaining instruments: reinvestments and policy interest rates that are expected to remain at their present levels well past the horizon of our net asset purchases.

As regards reinvestments, we will maintain the stock of securities in our portfolio for an extended period of time after the end of our net asset purchases and in any case for as long as necessary. As I have explained elsewhere[15], stock effects exert downward pressure on term premia. My colleague Benoît Cœuré recently referred to one further mechanism behind such a compression of term premia: the fact that, as price-sensitive investors offload their holdings of eligible securities onto the Eurosystem, the marginal seller to the programme becomes an investor type whose supply of securities is more rigid.[16] This perpetuates and in some cases even amplifies the effect of purchases on market prices.

Reinvestment is also consistent with a prudent policy approach because it means the duration leakage effect – which dampens the stimulus over time – will play out only gradually.

While reinvestment will be important to ensure that longer-term interest rates remain sufficiently supportive beyond the horizon of our net asset purchases, the ECB’s key interest rates and forward guidance on their expected evolution will once again become our principal means of steering the policy stance.

Our key interest rates are expected to remain at their present levels well past the end of net asset purchases, in line with our forward guidance. Financial markets are currently pricing our forward guidance on rates into the yield curve, which today is fostering steady progress towards a sustained adjustment. In the light of the interactions and complementarities between our different instruments, it will be important to monitor the reaction of the yield curve to the end of our net asset purchases.

With the passage of time, the indication that policy rates will remain at their present levels well past the end of net asset purchases will gradually cease to provide sufficient guidance about the likely evolution of the monetary policy stance. So, our forward guidance on the path of our policy rates will have to be further specified and calibrated as appropriate for inflation to remain on the sustained adjustment path towards levels below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

[1] I would like to thank Danielle Kedan for her support in preparing this speech.

[2] Praet, P. (2017), “Calibrating unconventional monetary policy”, speech at The ECB and its Watchers XVIII Conference, Frankfurt am Main, 6 April.

[3] For a summary of the literature on the effectiveness of non-standard measures, see ECB (2017), “Impact of the ECB’s non-standard measures on financing conditions: taking stock of recent evidence”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

[4] See also Praet, P. (2017), “The ECB’s monetary policy: past and present”, speech at the Febelfin Connect event, Brussels/Londerzeel, 16 March.

[5] The impact of credit easing is estimated on the basis of an event-study methodology which focuses on the announcement effects of the June-September 2014 package; see the ECB Economic Bulletin article entitled “The transmission of the ECB’s recent non-standard monetary policy measures” (Issue 7 / 2015). The impact of the deposit facility rate (DFR) cut rests on the announcement effects of the September 2014 DFR cut, while the impact of the subsequent DFR cuts is difficult to disentangle from the simultaneous APP adjustments. Therefore, both effects are shown jointly. APP encompasses the effects of the asset purchase measures adopted at the January and December 2015 Governing Council meetings, the March and December 2016 meetings and the October 2017 meeting. The January 2015 APP impact is estimated on the basis of two event-study exercises by considering a broad set of events that, starting from September 2014, have affected market expectations about the programme; see Altavilla, C. Carboni, G. and Motto, R. (2015) “Asset purchase programmes and financial markets: lessons from the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No 1864, and De Santis, R. (2016), “Impact of the asset purchase programme on euro area government bond yields using market news”, ECB Working Paper No 1939. The quantification of the impact of the December 2015 policy package on asset prices rests on a broad-based assessment comprising event studies and model-based counterfactual exercises. The impact of the March 2016 and December 2016 policy packages is assessed via model-based counterfactual exercises. The impact of the October 2017 policy package is assessed using two models: a term structure modelling framework similar to Li, C. and Wei, M. (2013), “Term Structure Modeling with Supply Factors and the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programs”, International Journal of Central Banking, 9(1), pp. 3-39 and an ISIN-by-ISIN regression framework akin to D’Amico, S. and King, T. B. (2013), “Flow and stock effects of large-scale treasury purchases: Evidence on the importance of local supply”, Journal of Financial Economics,108(2), pp. 425-448.

[6] To this end, for instance, an estimated term structure model is used following Li, C. and Wei, M. (2013), “Term Structure Modeling with Supply Factors and the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programs”, International Journal of Central Banking, 9(1), pp. 3-39. In this framework, yields are driven by three factors: the level and slope of the yield curve (‘yield factors’) as well as a factor related to the central bank’s bond holdings (‘quantity factor’). In quantifying the impact on bond yields, the model thus takes into account the effect of the central bank’s current and future expected bond holdings, including the impact of reinvestment.

[7] Euro area yields are proxied by the GDP-weighted long-term yield of the four largest euro area jurisdictions. The 10-year yield impacts are obtained from a version of the Li-Wei (2013) model used at the Federal Reserve to convert the SOMA portfolio of securities into yield impacts. Impacts are shown for different APP reinvestment scenarios, defined by the horizon indicated in the legend. The marginal impact of each additional year of reinvestment is given by the distance between the scenario curves. Latest observation: February 2018.

[8] Praet, P. (2017), “Maintaining price stability with unconventional monetary policy measures”, speech at the MMF Monetary and Financial Policy Conference, London, 2 October.

[9] See the euro area bank lending survey, October 2017.

[10] This chart shows the risk-neutral probability distribution function implied by 2-year zero-coupon inflation options. These risk-neutral probabilities may differ significantly from physical, or true, probabilities. They are estimated on the basis of call (“caplets”) and put options (“floorlets”) with different strike rates on the (three-month lagged) euro area HICP index excluding energy, food and tobacco, assuming Black-Scholes option pricing and implied volatilities that vary across strike rates (“volatility smile”).

[11] Brainard, W. (1967), “Uncertainty and the Effectiveness of Policy”, The American Economic Review, 57(2), pp. 411-425.

[12] Söderström, U. (2002), “Monetary Policy with Uncertain Parameters”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 104(1), pp. 125-145.

[13] APP expansion expectations are defined as the difference between median expected APP volumes according to Bloomberg surveys and the publicly announced overall envelope at the time of the survey. Inflation expectation deviations from the aim are derived as the difference between 1.9% and the 5-year-in-5-year inflation expectations implied by inflation-linked swap rates. Dashed vertical lines mark the first survey following each of the four APP recalibrations (survey dates: 14 December 2015; 18 April 2016; 16 January 2017; 11 December 2017). Latest observation: 2 March 2018.

[14] The “well past” horizon is derived as the difference between the date at which the forward curve prices in a full 10 basis point hike and the median expected APP end-date based on Bloomberg surveys. The grey area and the dashed section of the blue line refer to implicit “well past” intervals prior to the announcement of the “well past” communication on 10 March 2016. Inflation expectation deviations from the aim are derived as the difference between 1.9% and the 5-year-in-5-year inflation expectations implied by inflation-linked swap rates. Last observation: 19 January 2018 for the Bloomberg survey and inflation expectations, 20 February 2018 for the forward-implied lift-off horizon.

[15] Praet, P. (2017), “Maintaining price stability with unconventional monetary policy measures”, speech at the MMF Monetary and Financial Policy Conference, London, 2 October.

[16] Cœuré, B. (2018), “The persistence and signalling power of central bank asset purchase programmes”, speech at the 2018 US Monetary Policy Forum, New York City, 23 February.

Europejski Bank Centralny

Dyrekcja Generalna ds. Komunikacji

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Niemcy

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Przedruk dozwolony pod warunkiem podania źródła.

Kontakt z mediami