Policy rules and institutions in times of crisis

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB,at “Forum for EU-US Legal-Economic Affairs” organised by the Mentor Group,Rome, 15 September 2011

The economic and financial crisis we are experiencing – the worst since the war, let’s not forget – has called for economic policy responses that are unprecedented in their importance and in their nature. The central banks, in particular, have taken so-called unconventional measures to try to improve, and even to restore, the effectiveness of monetary policy in a context of financial instability. The fiscal authorities too have had to deal with new problems arising from excessive public debt and in some cases from a loss of confidence by financial markets.

These new circumstances have exposed a series of institutional problems related to the roles and responsibilities of various authorities at national and supranational level, a question which I would like consider today. One of the most discussed issues in recent months has been the risk of a confusion of roles, which may generate moral hazard and ultimately delegitimise the institutions and undermine their credibility.

In the European context, the question is posed in two specific dimensions. The first concerns the relationship between monetary policy and fiscal policy. The second concerns the relationship between the European and national institutions, specifically in respect of fiscal policy. Over the past 18 months we have been witnessing two important developments in Europe as a result of the crisis, involving both monetary policy and fiscal policy. The first one is the purchase of government bonds by the Eurosystem (the ECB and the national central banks) – the Securities Markets Programme (SMP) – and the second one is the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which will become the European Stabilisation Mechanism (ESM) after the Treaty has been amended.

Before explaining these two new resources, we need to take a step back and remember the two basic premises of monetary union. The first is monetary stability, defined as price stability. The second is the stability of public finances. The European Central Bank, an independent institution capable of deciding on a single monetary policy for the euro area, was created to achieve the first goal. The second goal however is based on two mechanisms: the Stability and Growth Pact, which binds the public finances of member countries; and the discipline imposed by the financial markets.

On paper, the framework seems almost perfect. A complete separation of monetary powers from fiscal powers creates the right incentives, so that each authority may effectively pursue its respective objective. The surveillance of fiscal policies ensures that these remain within predefined parameters, and if this does not happen sanctions are envisaged by the EU institutions and financial markets.

In reality, the framework is not perfect. The reason is that it relies on some simplifying assumptions, dear to economists, and perhaps even to lawyers. However, those assumptions do not always match the reality. Let me briefly illustrate two.

The first assumption concerns the deterministic nature of the framework, which does not consider the possibility of shocks, of forecast errors, of disruptive elements, all of which can cause crises, in particular public finance crises. In other words, the assumption was made – largely theoretical – that there would be no crises. Experience, both before and after the birth of the euro, however, shows that public finance problems may occur every so often, for various reasons. They could result from the infringement of established rules and inadequate supervision by multilateral institutions, as in the case of Greece. Or from the build-up of imbalances in the private sector, particularly banking, which become unsustainable and turn into public debt, as in the case of Ireland. Or lastly, they could even result from relatively low economic growth that, after a recession, reduces the room for manoeuvre for public finances and makes the debt dynamics unstable, as in the case of Portugal.

There are remedies for these construction defects, such as the strengthening of fiscal discipline and a better oversight of private debt – perhaps with more centralised powers for supervising the financial system, such as those that were recently adopted at European level. The initiatives that have been taken so far and are currently under discussion between the European Commission, the Council and Parliament are going in the right direction. They can be further strengthened. However, the possibility of a crisis and of a country losing access to financial markets can never be completely ruled out, especially in a context of global instability like the current one. We must not repeat the mistake of assuming that thanks to some “magic” Europe is immune to any crisis.

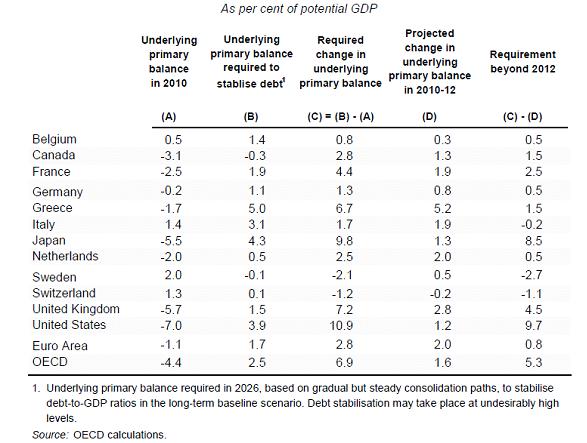

The second simplifying assumption that was made by the founding fathers is that markets work perfectly and can assess the various risks at any time, including those arising from an excessive accumulation of public debt. The experience of recent years has shown that this is not the case. For a long period – from approximately the start of the euro until about 2007 – markets assessed the credit risk of the various sovereign issuers in the euro area to be largely similar. Once the crisis broke out however, the assessment of the creditworthiness of European countries by the markets underwent a dramatic reversal and became for the euro area countries even worse than those of many emerging economies. Just to give an example, in early September, the CDS on the sovereign debt – which, by and large, measure the insurance cost against credit risk on sovereign bonds – of Italy and Spain were higher than those of Egypt, Lebanon, Vietnam and Romania. This result is not in line with the analysis of the fundamentals of various countries, as shown, for example, by the assessments, although questionable, of the rating agencies. Italy and Spain are A-rated, while Egypt, Lebanon and Vietnam are B-rated. Looking at the fiscal position of euro area members, it can easily be seen that the situation is much more favourable than several other advanced economies (see Table 1). Why is there such a dichotomy between fundamentals and market assessment?

Table 1: Consolidation requirements to stabilise debt over the long-term

We know that assessing sovereign credit risk is particularly difficult. It is a matter of evaluating, not only from an economic but also from a political perspective, the capacity and determination of a country to attain and maintain a primary budget surplus necessary to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio. One important factor is also the capacity to sell other financial and real estate assets in order to reduce the debt level. Moreover, there is limited post-war experience of debt problems in the advanced countries, and the cases of restructuring and default in recent years have only involved emerging countries.

We also know from numerous theoretical and empirical studies that when conditions are fraught with uncertainty or there are crises of confidence markets behave in unstable ways and fail to assess the fundamentals correctly and to price risk appropriately. We saw this after the US sub-prime crisis, when the values of some financial assets fell to ridiculously low levels, not justified by the fundamentals: the markets were unable to accurately assess the credit risk using the models and information available. The Federal Reserve bought securities with depressed values, which subsequently recovered, and it made a profit. There is extensive literature showing that in some circumstances the markets are subject to crises of confidence and self-fulfilling dynamics, worsening the instability. When a country loses access to the financial markets, it manages to regain it only after a relatively long period of time, even when it takes corrective measures agreed with the international institutions. In other words, even when a country is solvent and follows an appropriate fiscal policy it may not be able to borrow on the markets.

What I have just described does not however explain the paradox according to which six euro area countries are now being regarded as among the 20 riskiest countries worldwide. There are at least three other factors to bear in mind.

The creation of the single currency has led to an entirely new situation on the financial markets, one which has perhaps been underestimated not only by policy-makers but also by the economic literature. The euro area is in fact the only area in the world where monetary and fiscal institutions are completely separate, in which the fiscal authority cannot count on the monetary authority, not only to prevent a solvency problem, but also a liquidity problem. The implications of such a separation have not been studied thoroughly in the economic literature and further studies are surely desirable. [1]

On the one hand, such a separation is very healthy because it pushes the fiscal authorities to take all the necessary measures to ensure solvency. The framework works well but only to the extent that markets can properly assess the solvency of a country and calculate the risk premium, distinguishing solvency problems from liquidity problems. In other words, market discipline is effective and creates the right incentives if markets function properly.

But when markets do not work properly, because of the high level of uncertainty, because there is contagion or a general fear of systemic risk, market participants are no longer able to properly assess the risks and distinguish between them. Expected difficulties, even temporary ones, in meeting a borrower’s (sovereign’s) financing needs can cause expectations of a liquidity crisis and then create a perceived risk which may be reflected in the uncertainty about the price at which to sell a particular security, notably government bonds. Such a development, especially if it is prolonged, can degenerate into a solvency risk which jeopardises the economic and financial stability of the country and the whole area. In these circumstances there is a risk that conditions may arise that economists call “multiple equilibria”, in which the price does not necessarily reflect economic fundamentals. The transition from one equilibrium to the other is unpredictable and may be caused by speculative behaviours, which tend to be self-fulfilling. This phenomenon has been examined in the economic literature on the debt crisis inspired in turn by the analysis of the role of instability in the expectations relating to the bank crisis and bank runs originating from the famous work by Diamond and Dybvig in 1983 (Bank runs, deposit insurance and liquidity, Journal of Political Economy). [2]

When there is one fiscal authority and one monetary authority, it is more difficult for this type of instability to occur. Through its open market operations, the central bank in fact helps to keep markets liquid – starting with that of government securities, which represents the linchpin of the financial system and therefore of the monetary policy transmission mechanism – and thereby allows the market to price the various risks in line with the fundamentals and to transmit the monetary policy impulses to the economic system.

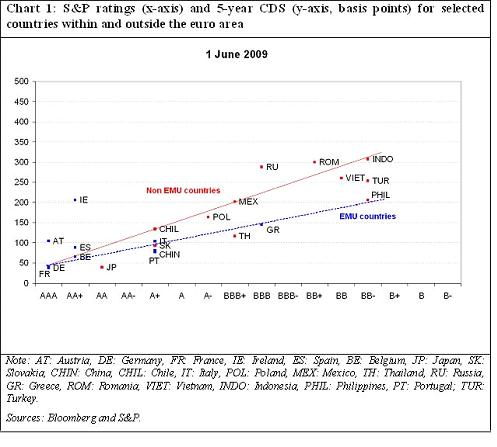

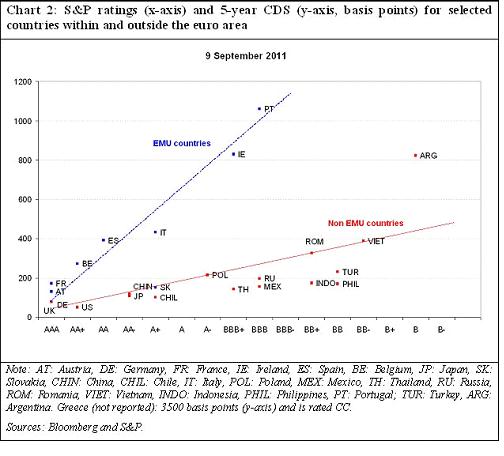

The second reason that may explain the assessment of excessive credit risk of the euro area countries is the own goal that European countries scored when they embraced the concept of private sector involvement in October 2010. I won’t go into detail, but in essence European countries have sought to deviate from the practice followed so far and, inspired by some academics and commentators, have tried to define an arrangement according to which a country must renegotiate with its creditors the conditions under which public debt securities were issued. This is another case in which the theory can deviate greatly from the practice and – especially in a context of general instability on the markets – intensify the crisis. The fact is that since last autumn euro area countries have been paying a specific risk premium which effectively penalises them.

Charts 1 and 2 seem to suggest that the concept of private sector involvement has introduced a sovereign risk premium specific to the euro area. On 21 July this year, the heads of state and government recognised that the case of Greece is special and that the modalitities to resolve the crisis will not be repeated. The fact the markets do not seem to believe it should induce the euro area authorities to be more convincing about such a statement.

When a crisis like the one we have been facing for several months occurs, it poses two problems of an institutional nature. The first concerns the relationship between the European authorities and the national ones. The second is about the relationship between the monetary and the fiscal authorities. In the European context, two innovative tools have been introduced in the last 16 months in Europe: the EFSF and the purchase of securities by the ECB, which may raise the question of the trade-off between moral hazard, i.e. the risk of encouraging opportunistic behaviour, and the need to keep the system stable. It is not a new dilemma, but in the context of the euro it takes on an unprecedented connotation which merits closer attention.

Let’s start with the relationship between the national fiscal authorities and the European authorities. It’s relevant to consider the case of a country that is solvent – i.e. is able and willing to take the necessary steps to generate a primary surplus, which helps to stabilise and reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio – but that has lost the confidence of the markets and has experienced difficulties to refinance itself. Let us look at the two extreme solutions first.

The first solution is to provide the country with full funding indefinitely and unconditionally. One way to do so is via the so-called eurobonds, which allow the country that has lost access to the market to continue to borrow at an interest rate near to or even equal to that of the most “virtuous” countries. Without stringent constraints, the eurobonds risk favouring fiscal policies that, on average, are more expansionary, and a higher debt, whose cost is also shared among the more disciplined countries. The experience of other countries, both federal and non-federal, outside the euro area, however, shows that a single federal budget is not necessarily more virtuous. On the contrary.

The other extreme solution is not to provide any financial aid, and to let the country to take the necessary measures to regain access to financial markets by itself. This solution, which is based on a blind faith in the ability of markets to discipline government budgets, may in some cases heighten the crisis of confidence and cause too drastic adjustments, which heighten the financial instability and cause contagion in other countries and markets.

Finding the right balance between the two extremes is not easy. The last 16 months of discussions among the euro area countries have shown the difficulty of creating a disciplinary framework that includes support mechanisms which avoid exacerbating the instability on the one hand and avoid moral hazard on the other hand. I do not want to reopen all the issues of this debate here. In reality, there was at global level an easy example to follow: the International Monetary Fund. The IMF provides financial assistance to countries in difficulty against strong conditionality, which obliges them to implement serious adjustment policies. The Fund’s assessment of a country’s solvency is based on independent analysis and decisions are made quickly. The proof that this system does not encourage moral hazard lies in the fact that countries in distress wait until the last moment before subjecting themselves to the Fund’s conditionality. In short, if you want to find the right balance between extreme solutions, you have to set up an institutional mechanism with some basic features – independence, accountability, operational effectiveness and decision-making capacity.

The EFSF is an attempt to create an institution with these characteristics. European countries have, however, had the ambition to improve the existing model of the IMF, with disappointing results, so much so that some changes were needed after less than a year. The decisions of 21 July this year are a move in the right direction and have to be quickly ratified by all the countries. In the future, further adjustments will probably be needed because the EFSF still contains some imperfections compared with the IMF.

The first problem concerns the decision-making mechanism. Currently it requires the consent of all members, a situation which allows each representative of the 13 countries (excluding Greece, Ireland and Portugal) to block or delay the timing of a decision. This does not seem very effective in order to intervene in a timely fashion in the markets. A second issue is flexibility. To be able to intervene on the primary and secondary markets, the procedures and methods must be flexible, in line with market developments. It takes all the safeguards of course – in terms of analysis, accountability and decision-making independence – to ensure that interventions do not create distortions on the markets.

I would now like to turn to the second demarcation line that is being discussed in this crisis, that between monetary policy and fiscal policy. In a financial crisis which is partly derived from excessive public debt, monetary policy should avoid covering the liabilities of fiscal policy and printing money to finance the public debt, thereby coming to the aid of the fiscal authorities and allowing them to postpone the adjustment – again a problem of moral hazard. On the other hand, the monetary authority must avoid that liquidity problems in the government debt market will turn into solvency problems hindering the conduct of monetary policy itself.

An extreme situation is one in which the central bank intervenes directly in the market for government securities and seeks to systematically influence yields. In this way the central bank actually takes away from the market the ability to assess the credit risk of public debt, turning it into an inflation risk. In a situation of low growth and low inflation, this risk tends to be undervalued by the markets. The budgetary authorities may in turn be led to believe that there is no problem of sustainability of public debt and no urgent need to take corrective measures. In fact, monetary policy takes the place of fiscal policy and over time part of the adjustment takes place through the inflation tax. The more active the central bank is in trying to influence bond yields, the less the incentive for the political authorities to take corrective budgetary measures – a sort of moral hazard in this case as well.

At the other extreme is the situation in which monetary policy never intervenes in the market for government securities, even when this is subject to instability. In other words, a situation arises that is similar to that in which public debt is fully denominated in foreign currency and national authorities have no chance to influence the conditions of the issuance. This is a rather unique situation, in which euro area countries find themselves.

The separation between fiscal and monetary authorities is optimal if the fiscal authorities are credible and if markets work perfectly and are able to accurately assess the credit risk of each issuer. In this case the market exercises a disciplinary constraint on the public issuers, which have to come to terms with market conditions and contain the debt. There are no problems of moral hazard.

The management of this rather unique system, like that which occurs in the euro area, must take into account two important aspects that distinguish theory from practice. The first is that conditions can be found in which markets do not work as the theory predicts. The second is that in advanced countries such as those in the euro area, the government securities market plays a central role in the functioning of the financial markets, and therefore the monetary policy transmission mechanism. I would like to make a brief reference to these two points.

First of all, we know that in reality markets rarely function as the theory predicts. This depends on several conditions which are generally considered valid in finance textbooks. Consider, for example, a simple model for valuing the bonds (which includes the valuation of government securities), based on the present value of future cash flows. In such a model, the cash flow, i.e. the coupon payments and the payments of the nominal value, is “discounted” using a risk-adjusted yield. This method permits a correct valuation of the price of a security only if some key assumptions are respected. Let me remind you of them briefly:

perfect markets, without friction, and especially with the absence of collusion and market power of the participants;

sufficiently liquid markets to ensure that investors can extract the appropriate, risk-adjusted yields from available market quotes and to guarantee that prices obtained from the model are indeed achievable in the market, should investors need to buy or sell the securities being priced.

the validity of the models relating to the term structure of interest rates; [3]

full availability of information;

the rationality of behaviour;

no arbitrage opportunities, so that the prices of all assets are priced fairly relative to each other, and under any circumstance.

As you can see, the situations in which markets are able to correctly assess prices may be the exception rather than the rule, particularly in times of financial stress.

This does not mean that markets should be abolished or that one should not take them into account. Rather, it means that we should be aware that there are situations in which markets are characterised by great instability and uncertainty, and cannot be entirely relied upon. One example involves situations in which there may be insufficient liquidity, so that it would not be possible for the main investors, individually, to sell or buy securities without greatly affecting their price. The fear of not being able to sell without making a loss may drive many market participants to rush the decision to sell, even suffering losses. In these cases, the perceived liquidity risk may result in a credit risk and can trigger price dynamics that are self-fulfilling. Since government bonds are one of the most important market segments for the economic and financial system, their impact on the real economy and financial stability in general can be significant.

If we recognise that markets do not always work perfectly, the following considerations must be inferred. First, it is not correct to subject only to the judgement of the market the suitability of the economic policy of a country, especially when this may involve highly destabilising effects for millions of people. I am not arguing that we should ignore market valuations, but we should be aware of the conditions in which such assessments are made; these valuations cannot be the sole reference parameter, at least for those who are responsible for the public good.

Second, faced with the imperfections of the market, intervention by an economic policy authority may be justified. This applies particularly when markets are subject to high uncertainty and the time horizon of market participants is getting shorter, making necessary a participant with a longer time horizon to counter market malfunctions. Even Milton Friedman recognised that in some circumstances the intervention of a public authority such as a central bank could be necessary to stabilise financial markets. [4]

The monetary authority tends to intervene to a limited extent in issues related to liquidity and the smooth functioning of markets, which influence the effectiveness of monetary policy itself. Given the importance of the government securities market in the financial system, its malfunctioning has a direct impact on the monetary policy transmission mechanism. This is done through three main channels: i) the influence that the interest rates on public debt have on the rates that banks pay on their liabilities, and then pass on to households and firms, ii) the effect of changes in the prices of government securities on the accounts of financial intermediaries, which in turn affects the ability of banks to provide credit to the real economy, iii) the ability to use government securities as collateral for refinancing in the money market or from the central bank, which influences the liquidity of the banking system.

Here I would like to refer to the second factor relating to the importance of the government securities market to the good functioning of monetary policy. In any basic textbook of macroeconomics – from Burda and Wyplosz to Mankiw – the operations of the central bank aimed at regulating the amount of liquidity in the system – the so-called open market operations – are essentially characterised by purchases and sales of government securities or the re-financing of the banking system against collateral (which often consists of government securities). The effectiveness of the various instruments depends largely on the structure of the financial market. In Anglo-Saxon countries, liquidity management typically occur through open market operations via the sale or purchase of government securities. This contributes to a correct price-setting mechanism in these markets. However, in countries where the banking system plays a dominant role and where there is no centralised market for government securities, such as the euro area countries, the injection or restriction of liquidity is done via repurchase agreements with the banks against collateral.

According to economic analysis the one kind of operation is not necessarily better than the other, and neither by itself can generate higher or lower inflation. It ultimately depends on the characteristics of the economic and financial system and on the impact on the total amount of money in circulation. The fact that in the past, whether recent or more distant, inflation has been created – notoriously in Germany – via outright financing of public debt does not mean that this type of open market operation is always inflationary, as the experience of many other countries shows, nor that other techniques permit an avoidance of inflation in any case.

When the government securities market is not working well, the monetary policy impulse, which comes from the short-term interest rate, is not properly transmitted to all other sectors of the financial system and then to the real economy. Non-conventional measures become necessary to try to circumvent bottlenecks in the system.

This is the spirit in which almost all central banks have adopted specific, and in many cases new, measures in recent months, demanded by the situation in which we find ourselves and adapted to the reality of the developed markets of our times.

The ECB in particular has adopted three specific measures, which are worth noting:

the refinancing of the banking system at different maturities, at fixed rate and full allotment against collateral. The European banking system has however ample collateral – more than €13 trillion – to be able to finance itself from the central bank;

the purchase of banks’ covered bonds to promote their liquidity at a time of market malfunction;

the purchase of government bonds of countries where the markets were seeing evident malfunctions that prevented a proper transmission of monetary policy.

The last type of intervention here has been the subject of much public discussion. In fact, intervening with purchases on the secondary market may influence the financing conditions of public budgets, and therefore this risks interfering with fiscal policy. It is interesting to note that the other two measures that directly relate to the financing of the banking system have not led to as many discussions, even though they also involve a risk of interference, specifically with the prudential supervisory authorities. Whenever the central bank issues liquidity via an operation which buys, for a specific time, a banking asset or a government security, it risks creating distortions in the relative prices of various financial assets. For this, procedures and safeguard mechanisms are needed. In the case of a loan to the banking system the banks need to be deemed healthy and operations need to be carried out in exchange for adequate collateral. In the case of purchases of securities, public or private, the underlying situation of the issuer has to be considered as healthy and the debt sustainable.

Not only the ECB, but all the central banks of developed countries have implemented measures geared to the difficulty of the situation. I would point to the extraordinary decision of the Swiss National Bank to set a minimum exchange rate for the Swiss franc vis-à-vis the euro, making massive euro purchases. It is worth mentioning that since 2007 the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve has increased by 229%, the Bank of England by 193%, the Swiss National Bank by 128%; the balance sheet of the Eurosystem has risen by 71%.

In conclusion, if in normal times it is possible – even easy – for the various institutions to follow simple rules of behaviour and to draw clear demarcation lines, within countries and between countries and at European level, in times of crisis the situation is more complex. On the one hand, we must avoid doing the job of others, taking away their incentive to adopt measures within their competence, thus creating moral hazard. On the other hand, we cannot hide behind principles and rules designed for a theoretical situation which no longer corresponds to the reality, and cannot give up fulfilling our responsibilities to avoid much worse situations. In crises, extreme solutions – activism with full discretion on the one hand, and total lack of action on the other – may seem easy to some, but such solutions are mistaken. A central bank buying government securities non-stop might appear to be useful, especially for the public finance authority, but it merely postpones the problem and may create inflation. A central bank that instead washes its hands of what is happening on the markets can be useful to others, perhaps for those who succeed in profiting from market instability, but it risks compromising the objective of price stability.

To allow each institution to operate in a balanced way, within its own responsibility and without exceeding it, it has to be assigned a precise task, given the independence to pursue it, and the obligation to account for its actions. This means that the institution must have the operational capacity and necessary autonomy to achieve its goals. Its actions must be subjected to scrutiny and even to criticism. But such criticism must check the consistency of its actions against the stipulated objective. To expatiate on the modi operandi of a central bank when it intervenes in times of crisis like the current one reminds me of the person who looks at the wise man’s finger, rather than what it is pointing to – according to an old Chinese proverb. [5]

As regards the European Central Bank, there is no doubt that it acts in full independence, with a clear primary objective, which is price stability in the euro area as a whole. In recent months, as in previous years, the ECB has taken – independently – measures commensurate with the gravity of the situation with the intent of pursuing the objective that it has been assigned. We are fully aware of the risks, related to a possible excess of activism on the one hand and benign neglect on the other. We have assumed our responsibilities in full, and seek to remind other institutions of theirs. We have explained the reason for our actions, the impact they have on market conditions and liquidity and its aims. We are subject to scrutiny by the public and the markets.

Anyone who thinks that the ECB has been excessively active on the market, for example on the market for government securities, or the opposite, must first of all demonstrate that such actions have not enabled the ECB to achieve its goal. I do not think there is any indicator – based on market expectations, those of professional forecasters and other indicators – which shows that any of the interventions implemented have undermined the ability of the ECB to maintain price stability in the euro area in the years to come. So I regard many of the criticisms of the ECB to be the result of inadequate economic analysis, of insufficient knowledge of the crisis in which we find ourselves and of anxiety resulting from experiences in the distant past that are not relevant to the current situation.

There is no doubt that we are going through a difficult period for the economic and financial stability of the euro area. The will to act in order to defend what we have gained is not enough; drawing up plans for the long term is not enough either. Rapid action is needed by various policy-makers, with each living up to his own responsibilities. The consolidation of public finances and the restoration of competitiveness at a global level are the top priority. This result is not possible in many countries without calling into question prerogatives and rights that until now were regarded as acquired, which nobody wants to give up, but which in the current situation means rent positions, privileges, preferential treatment.

There is no upcoming generation to whom we can pass the burden of adjustment. It’s up to this generation – in other words, us – to shoulder our own responsibilities.

-

[1]See, for example, P. De Grauwe, May 2011 “The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone”, CEPS Working Document, No. 346.

-

[2]See, inter alia, Calvo (1988), Servicing the Public Debt: The Role of Expectations, American Economic Review; Alesina, Prati and Tabellini (1989), Public Confidence and Debt Management, and Giavazzi and Pagano (1989), Confidence Crises and Public Debt Management (1989), both in Dornbusch and Draghi (Eds.), Public debt Management: Theory and History, Cambridge University Press.

-

[3]For example, C. Nelson and A. Siegel, 1987, Parsimonious modelling of yield curve, Journal of Business.

-

[4]Friedman and Schwartz (1963) have claimed that during the Great Depression many bank failures resulted from an “unjustified” panic and that many banks failed more because of liquidity problems than because of real insolvency. This is a typical case in which the intervention of the monetary authority, aiming to provide liquidity, can make a difference and save the real economy from a deep recession.

-

[5]“When the wise man points to the moon, the fool looks at his finger.”

Európai Központi Bank

Kommunikációs Főigazgatóság

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Németország

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A sokszorosítás a forrás megnevezésével engedélyezett.

Médiakapcsolatok