Globalisation, emu and the euro

Speech by Otmar Issing, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB34th Economic Conference 2006 on “Globalization: Opportunities and Challenges for the World, Europe and Austria”Vienna, 22 May 2006

Introduction

Let me first extend a warm thank to the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB) for inviting me here today to share a few thoughts on globalisation and the role played by the euro and the European and Economic Monetary Union (EMU).

In the last decades, Austria hosted a number of distinguished economists, such as Carl Menger, Friedrich von Wieser, Ludwig von Mises, Joseph Schumpeter, Friedrich von Hayek, who shaped the economic thought worldwide. In the context of this conference, it is useful to mention the “creative destruction” term, coined by Joseph Schumpeter in 1942 at Harvard after his migration to the United States. Schumpeter argued that the process of industrial mutation, which is intrinsic to capitalism, “revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”[1]

No doubt globalisation has a big “destruction” potential. To benefit from the global changes, countries need to be flexible and quick enough at adopting and spreading new technologies, risking in moving into new areas with big market opportunities in the future, which then translates in new jobs and higher economic growth.

The term “globalisation” has become one of the most fashionable buzzwords in contemporary political and economic debate. In an economic context, globalisation is associated with the growing economic linkages among countries through trade in goods and services, free cross-border capital flows, and more rapid and widespread diffusion of technology.[2] From a historical point of view, this is hardly a new phenomenon,[3] but over the past few decades this process has accelerated, as the time and costs necessary to connect distinct geographical locations have been drastically reduced. Indeed, geographical distance and national borders are much less important than previously, allowing firms to operate easily across national and geographical barriers. Multinational corporations, for example, typically manufacture their products in a wide variety of countries and sell to consumers around the world. And investment in financial markets can now be carried out directly on an international basis rather than through intermediaries, owing to economic deregulation and financial liberalisation, which have been underpinned by rapid advances in information and communication technology.

We can therefore safely conclude that globalisation has radically transformed our economic and financial landscapes. What I would like to do today is to discuss the inter-linkages between globalisation, EMU and the euro.

Before looking into this challenging issue, let me briefly talk about the creation of EMU in the context of globalisation.

The creation of EMU in the context of globalisation

EMU is the end-point of a long process towards monetary union, which started only a few years after the end of the Second World War. Its origin is rooted in the 1957 Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community. At this point Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands wished to remove economic barriers among Member States, but wanted to remain within the Bretton Woods system of stable exchange rates.

In 1969, when the Bretton Woods system appeared on the verge of collapse, the European leaders of the time were already thinking about creating their own alternative system of stable exchange rates among the European currencies. Three key initiatives leading towards EMU can be highlighted: the Werner Report in 1970, which introduced the concept of the “Snake in the Tunnel” that was later launched before the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1973; the European Monetary System in 1979, involving the introduction of the European Currency Unit; and the Delors Report in 1989, which is reflected in the Maastricht treaty in 1991. The years since 1969 depict a period of repeated attempts to establish a zone of exchange rate stability in (Western) Europe.[4]

These initiatives can also be seen in the context of the globalisation process. For example, the speculative attacks at the end of 1992, which deepened the exchange rate crisis in Europe, highlighted the increasing importance of exchange rate stability in an economic area with a single market. The policymakers’ challenge consisted of gradually creating a large economic area with monetary stability and where capital controls were progressively relaxed with the ultimate aim of establishing a monetary union large enough to defend itself against speculative attacks. Indeed, we can safely conclude that based on the experience of the last 7 and half years, a viable monetary union is a more credible commitment device than a fixed or quasi-fixed exchange rate regime. This process is still ongoing, because the euro is not only the currency shared by the 12 euro area countries, but is also the anchor for most of the other EU countries’ currencies.

In addition to influencing the economic and political debate in Europe in preparation for EMU, globalisation will also continue to shape the future of the global monetary system, once the Asian currencies and in particular the Chinese renminbi take a definite stance on their respective exchange rate regimes. The successful experience of EMU might encourage other economic areas to create new currencies and new joint central banks. Therefore, one might expect that globalisation will also affect the number of currencies currently circulating in the world. However, the creation of monetary unions requires a strong political commitment and forceful policy initiatives, as revealed by the EMU experience.

The economic impact of globalisation and the role of EMU

I would now like to turn to the main area of my paper and discuss, first, the economic impact of globalisation on economic linkages – most notably trade and capital flows – and second, the impact of EMU on regional financial integration and global portfolio reallocation.

Impact on trade, foreign direct investment and cross-border portfolio flows

The effects of globalisation are channelled via trade in goods and services, all of which has a tangible impact on businesses and households. Globalisation means that transport costs have decreased, technological innovations are more easily diffused, information is readily available at a low cost, and consumer tastes have been converging with an increasing number of global brands. Over the last three decades, tariffs have halved and a large number of trade agreements have entered into force between various countries. These developments have resulted in a steady opening of markets in Europe and around the world. In the early 1970s, for example, global exports accounted for only one-tenth of world GDP, compared with one-quarter today. The share of intermediate inputs in total trade flows is also at a historically high level, reflecting the dramatic deepening of global economic inter-linkages in recent years. Higher global demand and increase in the use of the euro in international trade have contributed to this new phenomenon. While intra-euro area trade has grown robustly since the introduction of the euro, extra-euro area trade has recorded even more rapid growth.

The effects of globalisation are also channelled via foreign direct investment (FDI). The role of multinational enterprises in the world economy has similarly grown over the years, as reflected in the expansion of the world’s FDI stock, which is almost equal to the annual GDP of the euro area. In many countries, the operations of foreign affiliates are now extremely important for domestic growth, with rising sales, value added, employment and exports. For the euro area, these international linkages are highly significant, particularly because economies of scale and cross-country technological spillovers support euro area economic growth. Euro area corporate businesses are among the most dynamic in the world, providing more than one-third of the world’s FDI stock. At the same time, almost one-third of world FDI is invested in euro area Member States. Intra-euro area FDI stocks have also grown robustly, increasing from almost 14% of euro area GDP in 1999 to around 24% by 2004.

Consumers clearly benefit from greater trade and FDI linkages via greater variety of goods and lower prices. However, adjustment costs, which are often front-loaded and concentrated on specific regions and sectors, also need to be taken into consideration. The change in the structure of the global economy requires individual countries to make structural adjustments through the determined implementation of structural reforms; such reforms are even more vital for countries in a monetary union. We know that the ability of a country to benefit from globalisation very much depends on the quality of its institutional and structural environment. All economies – including advanced ones such as the euro area – have to adapt to the changing needs of the world economy. Structural reforms in the labour, goods and capital markets are a key element of any long-run strategy to improve investment, growth and employment prospects, and are essential in order to face successfully the challenges ahead of population ageing, technological change and globalisation. The euro area has indeed undergone and will continue to undergo substantial structural changes, all of which are necessary and beneficial if the euro area is to secure a leading role in the global economy. Member States, therefore, need to stick to the implementation of their agreed reform agendas.

The impact of globalisation is also apparent in the sharp increases in cross-border portfolio flows observed since the beginning of the 1990s, a process that continues to be encouraged by the substantial number of bilateral investment treaties, the liberalisation of capital accounts, and technological advances in payment, settlement and trading systems as well as financial information systems, which tend to reduce information asymmetries. Since the beginning of the 1990s, countries have accumulated foreign portfolio assets equivalent to almost half of the annual world GDP, up from just one-third in 1997, and a small fraction in the 1970s and 1980s. Similarly, in 2005 euro area residents held foreign portfolio holdings with a total value of approximately 3.5 trillion euro, a figure that is almost half of euro area’s annual GDP.

Cross-border financial linkages, new financial products and the possibility of more accurate and wider risk-sharing have however also raised the level of interrelations across national financial markets. This implies that financial systems are more exposed to common risks, as financial disturbances may be transmitted more easily across borders in periods of turbulence. As a result, sceptics have indeed expressed concerns about the sustainability of global financial integration, which is regarded by some as having the potential to destabilise the global economy. But there is also an opposing view according to which global financial integration reduces the risks to the global economy, for which there are convincing arguments.

In this respect, empirical evidence suggests that the strongest determinants of the global portfolio reallocation over the 1997-2001 period were (1) the need to diversify the risks of holding foreign portfolio assets across several countries, and (2) the willingness to close the gap between actual and optimal shares of foreign investment, which suggests that rational portfolio optimisation was the primary motivation behind investors’ reallocation of their international portfolios. This has two main implications: first, that investors do not ignore the main principles of portfolio theory; and second, that portfolio investments might be less prone to boom and bust cycles, being driven by long-term economic fundamentals.[5]

The overall effects of global financial integration on the stability of the financial sector can be expected to be positive in the long run, because greater liquidity and the adoption of risk-sharing and risk-mitigating techniques both strengthen the overall resilience and shock-absorption capacity of the global financial system. Cross-border capital flows not only benefit the recipient economies, but also the countries of origin, as they facilitate international risk-sharing and participation in returns abroad. Trade in goods and services and cross-border capital flows have clearly increased the spillovers of macroeconomic fluctuations globally.[6] However, one should welcome the recent developments in international financial integration, because they reflect trends towards an efficient allocation of resources and, in this way, support growth and promote welfare in the global economy.

How much further will financial globalisation deepen? In order to answer this question, we examine developments in countries’ home bias, i.e. how much investors prefer to invest in domestic assets rather than fully diversifying their portfolio internationally.[7] In a world without transaction and information costs, all countries would hold the same portfolio and would diversify their investment in other countries in proportion to the size of their financial markets.[8] In such an ideal scenario, each economy would be perfectly positioned to withstand economic shocks. This portfolio theory provides a benchmark for assessing the degree of financial integration in a given country.

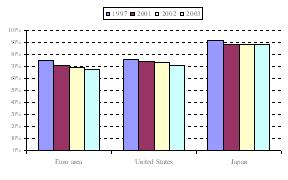

Over the last decade many countries have indeed been reducing their risk positions in equity markets through this mechanism, and in several developed countries the tendency to invest in domestic equity assets has decreased. However, the latter are still far from having a theoretically optimal portfolio, i.e. one with a zero home bias. In 2003, equity home bias amounted to 70% in the euro area and the US, and almost 90% in Japan (see Chart 1).[9]

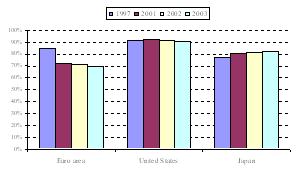

The degree of home bias in the fixed income market is also high, and has only decreased over time in the euro area (see Chart 2).

| Chart 1. Home bias in the equity market for the euro area, the US and Japan (annual data) | Chart 2. Home bias in the debt instruments market for the euro area, the US and Japan (annual data) |

|

|

| Sources: IMF, Thomson Financial DataStream, ECB calculations. Note: The home bias of the euro area is computed excluding intra-euro area asset trade allocation. | Sources: BIS, IMF, ECB calculations. Note: The home bias of the euro area is computed excluding intra-euro area asset trade allocation. |

We can, therefore, say that the global tendency to invest in the home market has been declining, albeit possibly more slowly than one would have expected, and only in the equity market. This is because the tendency to invest more in international markets – as reflected in the surge in cross-border portfolio flows – has been accompanied by the tendency of households to shift part of their savings towards riskier domestic assets, as the sharp rise in countries’ domestic market capitalisation reveals.

What can we say about the future? We should expect that home bias will continue to decline, most likely at a slow pace, because investors need to perceive that diversifying their global portfolio more and more on a global scale will reduce risk; for that they need to become more familiar with the international environment.

Impact of EMU on portfolio reallocation and financial integration

Did EMU play a role in the reallocation of capital worldwide and on financial integration? To answer this question, we need to remind us what a monetary union implies. The elimination of the exchange rate risk is the first obvious implication, which is also a feature of other fixed exchange rate regimes. But the fundamental difference is that – when EMU was established – Member States committed to irrevocable conversion rates of their currencies. A second important factor is related to the effect of EMU on the business cycle of Member States, the consequent impact on asset returns and, as a result, on portfolio diversification by international investors. A third crucial factor, which could have influenced the reallocation of portfolio holdings, is the catalyst effect of the single currency arising from the reduction/elimination of cross-border barriers, which enhanced financial integration particularly among the Member States.

In order to assess whether EMU did play a role in the reallocation of portfolio holdings worldwide and on financial integration, we can look at countries’ home bias measures as well as the cross-border investment in euro area portfolio assets.

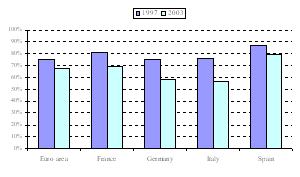

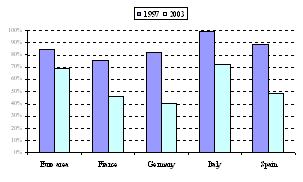

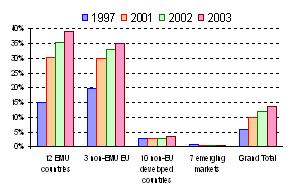

While home bias for the euro area as a whole – treated as one economic entity – has decreased somewhat, particularly in the fixed income markets, in some cases it has declined enormously for individual euro area Member States (see Charts 3-4).

In Italy, for instance, the value of debt instruments held by residents is much lower than in 1997, when the majority of these instruments were issued domestically thanks also to the relatively higher level of interest rates that prevailed before EMU (see Chart 4). The decrease in home bias among individual Member States has been more pronounced for debt instrument holdings than equity holdings. This implies that euro area investors have reallocated their portfolio holdings within the euro area, as a consequence of the establishment of EMU.

| Chart 3. Home bias in the equity market among euro area countries (annual data) | Chart 4. Home bias in the debt instrument market among euro area countries (annual data) |

|

|

| Sources: IMF, Thomson Financial DataStream, ECB calculations. Note: The home bias of the euro area is computed excluding intra-euro area asset trade allocation. | Sources: BIS, IMF, ECB calculations. Note: The home bias of the euro area is computed excluding intra-euro area asset trade allocation. |

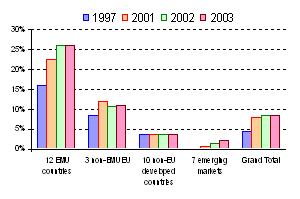

Indeed, a simple inspection of the data reveals that European countries increased their holdings of euro area international assets (as a share of their total international portfolio) between 1997 and 2003 (see Charts 5-6).[10] Over this period, the share of intra-euro area allocation increased markedly by 10 percentage points for equity portfolios and by almost 25 percentage points for fixed income portfolios.

Moreover, global financial integration was accompanied by a large shift in holdings towards the euro area countries, thereby favouring international risk-sharing vis-à-vis the euro area, particularly with regard to other European countries and, to a lower extent, with respect to emerging markets in equity portfolios (see Charts 5 and 6).[11]

| Chart 5. International allocation of euro area equity assets relative to total equity holdings by region (percentage) | Chart 6. International allocation of euro area debt instrument assets relative to total debt instrument holdings by region (percentage) |

|

|

| Sources: IMF, Thomson Financial DataStream, ECB calculations. Note: Country groupings are listed in footnote 10. 12 EMU countries = Share of intra euro area non-domestic assets in total euro area holdings. Other country groupings = Share of euro area assets held by non-euro area residents in total non-euro area residents’ holdings | Sources: BIS, IMF, ECB calculations. Note: Country groupings are listed in footnote 10. 12 EMU countries = Share of intra euro area non-domestic assets in total euro area holdings. Other country groupings = Share of euro area assets held by non-euro area residents in total non-euro area residents’ holdings |

One important conclusion can be drawn from this analysis. By reducing the barriers for cross-border portfolio allocation, EMU has had an impact on regional financial integration not only among euro area member states, but also vis-à-vis other European countries, which is particularly sizeable in the fixed income market.

This brings me on to one of the key achievements since the creation of EMU: namely, the fostering of European financial integration, which goes well beyond the mere elimination of the exchange rate risk.[12] By providing a higher degree of financial integration, EMU has enhanced risk-sharing among participating Member States and contributed to a smooth and effective implementation of monetary policy in the euro area. [13]

To sum up, from a global perspective, the establishment of EMU in January 1999 represents a fundamental institutional change in the world economy, and could in part help explain the large reallocation of capital that has taken place worldwide.

The euro area – a zone of stability

Before concluding, let me emphasise that since 1999 we have experienced a number of important shocks to the global economy, such as the Y2K problem at the turn of the millennium, substantial oil price increases, the fall and the rise of the euro exchange rate, the boom and burst of the equity market bubble, global imbalances and the clouds of war and terrorism. Amidst all of this, the ECB has guided inflation expectations consistent with price stability and thus provided a reliable anchor for the euro area economy, while the euro has sheltered euro area financial markets against those shocks.

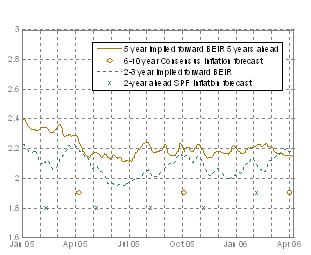

Indeed, long-term forward break-even inflation rates – which measure inflation expectations and the corresponding inflation risk premium over a horizon in the more distant future – have remained remarkably stable in recent years in the euro area, at a level only moderately above 2% and thus only slightly above comparable survey expectations (see Chart 7). This indicates that the ECB has been very successful in firmly anchoring long-term inflation expectations at a level consistent with its definition of price stability that is below 2% over the medium term.

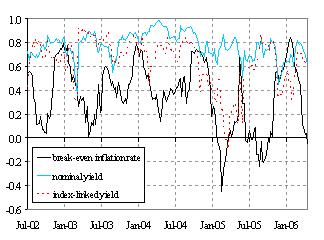

| Chart 7: Implied forward break-even inflation rates and comparable Consensus Economics inflation expectations (% p.a.; five-day moving averages of daily data (BEIRs): Jan. 2005 to Apr. 2006) | Chart 8: Correlation of weekly changes in 10-year nominal and index-linked government bond yields and break-even inflation rates between the euro area and the US (12-week moving averages: Jul. 2002 to Apr. 2006) |

|

|

| Sources: Reuters, Consensus Economics, ECB calculations. | Sources: Reuters, ECB calculations. |

As pointed out by Malcom Knight, extracting “clean” information about domestic economic developments from financial market indicators in a more globalised world has undoubtedly become much more arduous.

However, the break-even inflation rate (i.e. the yield differential between conventional nominal and inflation-linked bonds) predominantly reflects market expectations of domestic inflationary trends. Correlation analysis suggests that, while short-term fluctuations in nominal as well as index-linked bond yields tend to be quite closely synchronised between the euro area and the US, the relationship between euro area and US break-even inflation rates tends to be very weak (see Chart 8). Only in times when inflation expectations react to common global inflationary shocks, for example to strong increases in oil prices, can a closer synchronisation of movements in break-even inflation rates be observed.

How would the European economy have developed had the euro not been introduced? We can only speculate, but past experience can be quite instructive. We must not forget that, as a consequence of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the world’s first major oil crisis, the 1970s were a period of monetary disintegration in Europe. Nor should we forget the devaluation of the Italian lira by almost 30% against the Deutsche Mark after the 1992 ERM crises. The exchange rate risk premium, which is believed to have been a major determinant of interest rates before the introduction of the euro, would have increased the spreads on government bond yields across Member States with adverse effects on countries with large debt ratios.[14] In all likelihood, therefore, a currency crisis in Europe may well have arisen, with speculative attacks on weaker currencies leading to large devaluations. Most likely, the existence of the European single market would also have been challenged in such a situation, given the sequence of abrupt shifts in competitiveness between EU Member States.

Globalisation, by contrast, has promoted diversification and allowed risks to be spread across regions. Regional and global financial integration as well as internal stability have shielded the euro area against potential speculative attacks on the euro with all their negative consequences.

But the euro is far from a universal panacea. Countries must make flexible adjustments to their product and labour markets in order to increase the potential output of the euro area and to reduce the still intolerably high unemployment rate. Establishing competitive, efficient and well-functioning markets is essential in order to enhance medium to long-term economic growth, to facilitate the adjustment process, and to increase the resilience of the euro area to economic shocks.

In this respect, the globalisation process itself should induce policymakers to take unpopular decisions while ensuring fiscal discipline. For a monetary union to work, sound fiscal policies are a prerequisite. Therefore, Member States must adhere to the criteria set out in the Growth and Stability Pact.

But is it possible, as some have argued, to promote growth and structural reform at the same time as encouraging further fiscal consolidation? My answer is a clear yes. There is no evidence for such a trade-off. On the contrary, countries that have in the past undertaken consolidation measures as part of a comprehensive reform agenda have fared best both in terms of boosting growth and sound public finances. These countries (e.g. Ireland in the late 1980s and Spain and some others in the mid-1990s) have benefited from strong supply-side effects on growth and – rather quickly – from the confidence effects of reform, which mitigated the adverse demand effects of fiscal consolidation.[15]

So, given this evidence, if euro area countries are to benefit fully from the globalisation process, attaining sound public finances is a prerequisite.

Concluding remarks

Let me now conclude, in what is going to be my last public speech as a member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank. By coincidence, – on 8 May 1998 –, just before the beginning of my mandate at the ECB , I gave a speech in Vienna at that year conference organised by the OeNB (title of the speech: Welche geldpolitische Strategie für die EZB?). I am again back in Vienna at the end of my mandate.

Distinguished economists have often criticised the very concept of European Monetary Union, mainly because the Member States in question did not fulfil optimum currency area criteria, having for example a low degree of labour mobility, inflexible real wages as well as sharp differences in commodity prices and segmented financial markets. At this point, I have to confess that I too was sceptical for similar reasons, also because I have always argued that unsound government fiscal policies would ultimately discredit the efforts of monetary policymakers to fight inflation. However, at the same time, I also believed that, if all countries did their homework and the Maastricht Treaty criteria were met, I could envisage a successful monetary union – although, to be honest, in the first half of the 1990s I did not think it would be possible for 11 European countries to achieve price stability at the start of Monetary Union.

In 1998, at my hearing in front of the European Parliament, I said:

“The introduction of the euro will reshape the face of Europe. It is the most significant event in the international monetary and financial world since the end of the Second World War. But the euro will only be able to play its intended role if it becomes a stable currency. To achieve this, the Maastricht Treaty has given the European Central Bank (ECB) clear priority for the objective of price stability and has granted its decision-makers independence so as to be able to take the necessary decisions.”

I believe that we have fulfilled our mandate. By pursuing price stability in the euro area, we have also made a positive contribution to stability worldwide. The euro is not only a very stable currency, but has also become the world’s second international currency, after the US dollar. Moreover, EMU has affected global capital reallocation, attracting FDI as well as portfolio investment, and has enhanced regional financial integration among euro area Member States.

Let me therefore underline my firm belief that the euro is an undoubted financial and monetary success because the people who use it around the world believe in its stability.

References

Briotti, M. G. (2005), “Economic reactions to public finance consolidation: A survey of the literature”, ECB Occasional Paper Series, n. 38.

Coval, J. D. and Moskowitz, T. J (1999), “Home bias at home: Local equity preference in domestic portfolios”, Journal of Finance, 54: 2045-2073.

ECB (2005), Indicators of financial integration in the euro area, Frankfurt am Main.

ECB (2006), Fiscal policies and financial markets, Monthly Bulletin, February: 71-84.

De Santis, R. and Gérard, B. (2006), “Financial integration, international portfolio choice and the European Monetary Union”, ECB Working Paper Series, n. 626.

French, K. R. and Poterba, J. M. (1991), “Investor diversification and international equity markets, American Economic Review, 81: 222-226.

Huberman, G. (2001), “Familiarity breeds investment”, Review of Financial Studies, 14: 659-680.

IMF (1997), World Economic Outlook, Washington DC, May.

Issing, O. (2006), “Europe’s hard fix: The euro area”, contribution to a workshop on “Regional and International Currency Arrangements”, Vienna, 24 February 2006. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2006/html/sp060224_1.en.html

Kose, M. A., Prasad, E. and Terrones, M. E., 2003, “How does globalization affect the synchronization of business cycles?”, American Economic Review, 93: 57-62.

Obstfeld, M. and Taylor, A. M. (2005), Global Capital Markets. Integration, Crisis, and Growth, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1976), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York: Harper (orig. pub. 1942).

Solnik, B. (1974), “An equilibrium model of the international capital markets”, Journal of Economic Theory, 8: 500-524.

Sorensen, B. and Yosha, O. (1998), “International risk sharing and European monetary unification”, Journal of International Economics, 45: 211-238.

Williamson, J. G. (1996), “Globalization, convergence, and history”, Journal of Economic History, 56: 277-306.

-

[1] Schumpeter (1976, p. 83).

-

[2] See IMF (1997).

-

[3] For a historical overview of globalisation and its economic implications, see Williamson (1996), and Obstfeld and Taylor (2005).

-

[4] For a comprehensive analysis on the implications of alternative exchange rate regimes, see Issing (2006).

-

[5] For a comprehensive analysis on the determinants of global portfolio reallocation, see De Santis and Gérard (2006).

-

[6] See Kose et al. (2003) for an assessment of the impact of globalisation on the synchronisation of business cycles.http://www.iza.org/en/webcontent/publications/papers/viewAbstract?dp_id=702

-

[7] See for example French and Poterba (1991), Coval and Moskowitz (1999) and Huberman (2001).

-

[8] See Solnik (1974).

-

[9] De Santis and Gérard (2006) provide the methodology here adopted to compute home bias measures.

-

[10] 12 EMU countries consists of the 12 euro area countries. “Other EU countries” refers to Denmark, Sweden and the United Kingdom. “Non-EU developed countries” comprises ten other developed countries: Australia, Bermuda, Canada, Iceland, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and the US. “Emerging markets” is formed by 7 countries: four Asian emerging markets (Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia and Thailand) and three Latin American emerging markets (Argentina, Chile and Venezuela).

-

[11] A more sophisticated analysis based on an international portfolio choice model reaches the same conclusion (see De Santis and Gérard, 2006). EMU has enhanced regional financial integration in the euro area in both the equity and bond markets. There is evidence of active trading among euro area Member States, with euro area investors assigning a higher weight to portfolio investment in euro area countries. Over the period 1997-2001, the average increase in weights - on top of the world average portfolio weight increase in euro area assets - amounts to 12.7 percentage points for equity holdings and 22.4 percentage points for bond and note holdings.

-

[12] See ECB (2005).

-

[13] On international risk sharing and EMU see for example Sorensen and Yosha (1998).

-

[14] Budget balances for 2005, broadly ranging between a 2% of GDP surplus and a 5% deficit, and debt ratios varying from 7% to 108% of GDP, are accompanied by differences in the interest rates on government bonds of around 30 basis points at most. Ten years before, when spreads still included substantial exchange rate risk premia, they exceeded 600 basis points, with budget balances ranging from a 3% of GDP surplus to a 10% deficit, and debt ratios varying from 7% to 133% of GDP (ECB, 2006).

-

[15] For a survey of the literature on the impact on growth of contractionary fiscal policies, see Briotti (2005).

Europejski Bank Centralny

Dyrekcja Generalna ds. Komunikacji

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Niemcy

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Przedruk dozwolony pod warunkiem podania źródła.

Kontakt z mediami