Monetary policy and asset prices

Opening address by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBFreiburg, 14 October 2009

Introduction [1]

It is a great pleasure to take part in this ceremony at the University of Freiburg.

Freiburg has traditionally provided a nurturing environment for economic ideas. Some of these ideas have exerted a strong influence on the design of economic systems and institutions. When Walter Eucken was recommending that monetary policy should be the responsibility of a central bank committed to price stability and independent from political pressures, his was a minority view in international academic circles and among most policy-makers. It has since become best practice.

The recent financial crisis has led some observers to question the role of monetary policy, in particular with respect to its objectives. Is price stability too narrow an objective? Should monetary policy also be entrusted with the objective of preserving financial stability? After all, the last two decades have witnessed the coexistence of, on one hand, relatively low and stable inflation in large parts of the globe and, on the other hand, the dot-com boom and bust at the turn of the millennium and the financial crisis we are still experiencing. Some have even argued that a monetary policy too narrowly focussed on price stability might actually fuel asset price bubbles. These questions, and how they are addressed by the ECB’s monetary policy strategy, will be the focus of my remarks. In this speech I will take a longer-term perspective, without dwelling on the shorter-term prospects for the course of monetary policy in the euro area.

Let me state my conclusions up front. The appropriate primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain price stability over the medium term. Financial stability is best ensured through instruments other than the policy interest rate and in the context of a broader framework of macro-prudential supervision. Nevertheless, a central bank should actively monitor asset prices and credit flows. The evolution in these variables provides timely and useful information, which helps to better calibrate the course of monetary policy and to avoid the risk of being “behind the curve”.

1. Monetary policy and asset prices: the pre-crisis consensus view

A good starting point for my analysis is a brief summary of the “pre-crisis” consensus view about the relationship between monetary policy and asset prices. I stress: “pre-crisis”. There is no “post-crisis” consensus view yet. However, recent events have shaken so profoundly the conventional wisdom prevailing before the crisis that it is unlikely to remain unchanged.

The pre-crisis consensus view was firmly grounded in the dominant new-Keynesian paradigm for monetary policy analysis, which builds upon models where financial conditions play at most a very limited role. [2] Within that framework, financial market conditions, such as developments in asset prices or in the quantity of money and credit, do not affect macroeconomic outcomes, or the transmission of monetary policy. They may reflect, or even anticipate, underlying economic conditions, but they do not provide any feedback on those conditions. The pre-crisis consensus view also rested on a presumption that strong asset price dynamics and misalignments tend to be associated with strong inflationary pressure. As a result, a central bank responding to inflation would in any case also automatically address financial imbalances, because financial imbalances would coincide with upward pressure on inflation.

Starting from these premises, there is clearly no reason for monetary policy to react to specific financial market developments. Of course, a central bank may want to monitor financial and monetary developments, which should be factored into the policy process to the extent that they contain information about the inflation outlook at a specific policy horizon (usually two years). This also explains the emphasis put by the consensus view on the output gap as the main determinant of inflation.

The pre-crisis consensus view also relied on three additional reservations against an explicit monetary policy reaction to financial imbalances. [3]

First, doubts were expressed about the ability of central banks to identify asset price misalignments early on and with a sufficient degree of confidence. Central banks do not have better information than financial markets, and misalignments can only be identified with certainty with the benefit of hindsight.

Second, questions were posed about the effectiveness of moderate interest rate increases in curtailing the bubble. A monetary policy tightening of moderate size would not be able to counterbalance the prospect of large capital gains normally available during a boom in asset price. And strong policy-rate hikes would not be a viable option either, as they may pose serious risks to the economy.

Third, it was pointed out that a decisive easing of the monetary policy stance after the bursting of the bubble would be sufficient to avoid substantial economic damages. The central bank should simply be ready to intervene aggressively by slashing policy rates after the collapse of asset prices in order to sustain real economic activity and minimise the probability of deflation.

2. Risks associated with the pre-crisis consensus view

Let me mention two main risks associated with the pre-crisis consensus view.

2.1 Delayed removal of policy accommodation

The first risk is that the implementation of such an approach might favour a policy of “tolerance” and “benign neglect” during the boom phase and a policy of excessive accommodation during the bust phase. When this is compounded with the central bank’s legitimate fear that a premature removal of policy accommodation may weigh negatively on the (initially still fragile) recovery, exceptional accommodation in terms of low levels of policy rates may also become exceptional accommodation in terms of the duration of such a policy. Delaying or diluting the removal of policy accommodation as inflationary pressure associated with a turn-around of the economic cycle gradually builds up runs the risk of leaving the central bank behind the curve.

This risk seems to be an intrinsic feature of the asymmetric policy response to the boom and bust phases of an asset price bubble which characterises the pre-crisis consensus view. The counter-argument, that the central bank could successfully correct this outcome by simply raising policy rates later on as inflationary pressures eventually emerge, does not consider the transmission lags of monetary policy and the role of inflation expectations. A belated monetary policy response would require much stronger, and thus more painful, action to be taken at a later stage to regain control of inflation expectations. Indeed, the longer interest rates are kept at low levels, the greater is the incentive provided to investors to hold long term assets, possibly leveraging with carry trade, and the greater the capital loss occurring when rates are eventually raised. The potential future costs often do not receive appropriate weight in the policy considerations.

Another less obvious outcome of a hesitant and belated removal of policy accommodation is that it could set in motion a chain of events that will ultimately create new financial imbalances with potentially high risks for price stability and for the economy as a whole. Feedback-loop models provide a simple, yet powerful, analytical framework to illustrate some of the channels that may be at work. Consider the following stylised course of events. Excessively low policy rates stimulate economic activity and improve non-financial and financial firms’ profitability, providing an initial boost to asset prices. Low interest rates and expanding activity encourage demand for credit. Lenders become more willing to accommodate this demand and to charge lower premiums on the basis of the higher value of collateral associated with higher asset valuations. The greater availability of credit leads to more assets being bought, thus boosting their price. This sets in motion a self-sustaining feedback loop. This endogenous cycle can become even stronger if accommodative monetary policy contributes to a lowering of credit standards applied by lenders and to a lower perception of risk – as suggested by the risk-taking channel. [4] All these effects provide the main ingredients for an asset price bubble and the building-up of financial imbalances.

When the day of reckoning comes, the loop will work in reverse. The pre-crisis consensus view requires at that point an extremely accommodative reaction by the central bank. Undoubtedly, this kind of monetary policy gives the illusory impression that structural adjustments can be postponed or, worse, are not necessary at all, thus paving the way for a second boom and bust. I believe that more attention should be paid to the inter-temporal dimension of this kind of policy. It is aimed at improving the situation in the short run, while disregarding completely the risks of triggering new imbalances in the future. Ignoring this inter-temporal dimension may also weigh negatively on the credibility of public institutions. As the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises lucidly expressed it: “ The individual is always ready to ascribe his good luck to his own efficiency and to take it as a well-deserved reward for his talent, application, and probity. But reverses of fortune he always charges to other people, and most of all to the absurdity of social and political institutions. He does not blame the authorities for having fostered the boom. He reviles them for the inevitable collapse. In the opinion of the public, more inflation and more credit expansion are the only remedy against the evils which inflation and credit expansion have brought about.” [5]

The idea that the recent financial crisis can be traced back at least partly to monetary policy excesses at the global level at the beginning of the decade has found some support in the empirical literature. For example, John Taylor has argued that, had the Federal Reserve implemented less expansionary policies over the period 2002-04 and followed a path for interest rates more in line with established regularities, the US housing boom would have been smaller than it actually was. [6] Other analysts have argued, however, that during the years preceding the crisis, on the basis of cross-country evidence, there is no clear-cut association between the stance of monetary policy and house price increases. [7] The final judgement is still pending.

2.2 Readiness to act may prove insufficient

The second risk associated with the pre-crisis consensus view is that, even when a central bank is ready and willing to act swiftly, this may prove to be insufficient. In particular, the emphasis which the pre-crisis consensus view puts on the output gap and on the inflation forecast at a given horizon may prevent the central bank from identifying the right signals for the appropriate timing of policy actions.

There is extensive literature analysing the challenges for the conduct of monetary policy arising from excessive emphasis on the output gap, i.e. the difference between the level of output and its potential, estimated under the assumption of full utilisation of resources. Real-time estimates of potential output tend to be quite inaccurate. [8] The extent of the revisions in the measurement of the output gap is so large that often the picture of the state of the economy provided by this statistic at a particular date is turned upside down subsequently. The revision process lasts for many years, so it can be a long time before we know with some confidence the sign and magnitude of the output gap at any particular point in time in the past.

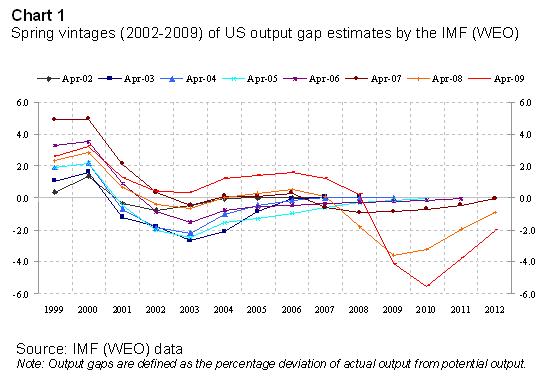

Chart 1 provides a vivid example of this problem. It displays alternative vintages of output-gap estimates for the United States as calculated by the IMF. Consider, for instance, spring 2005, when the Federal Funds Target Rate was at the relatively low level of 2.75%. The initial estimate of the output gap was negative at -1.3%. Two years later it was revised upwards to 0.1%, and four years later, in 2009, it was revised upwards again to positive territory 1.4%. Interestingly, the latest estimate suggests that the US output gap was never in negative territory over the last decade, not even between 2001 and 2005.

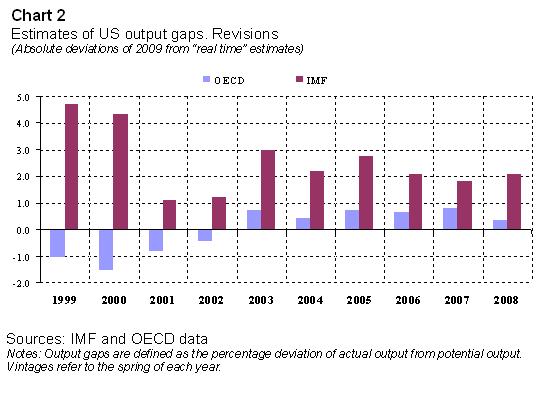

Large subsequent revisions of the output gap are not confined to specific years, but are a pervasive feature. Chart 2 shows the actual size of these revisions as estimated by the OECD and the IMF in spring 2009. The size of revisions and the disparity between the different sources is striking.

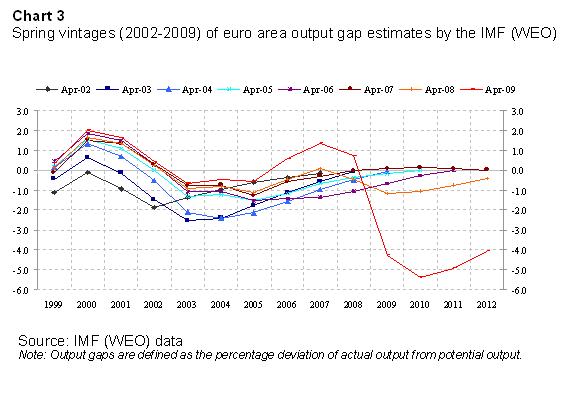

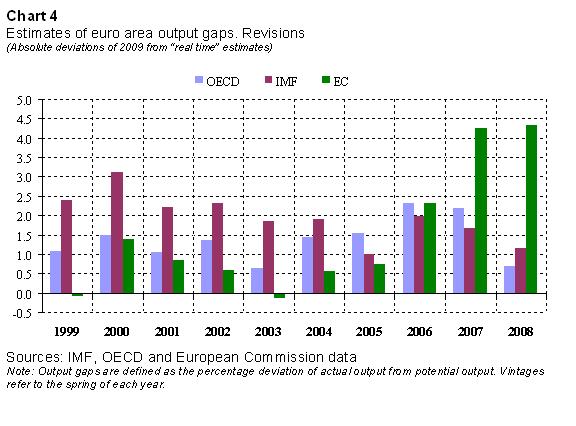

Euro area output gap estimates are also characterised by a large degree of revision, and there is an equally large disagreement between different sources, as documented in Charts 3 and 4. However, the latest estimates do suggest that the euro area had a negative output gap in the period 2002-2005.

Overall, the unreliability of measures of the output gap affects the appropriateness of monetary policy prescriptions that are predicated on such a construct. And, in all likelihood, output-gap estimates are going to become more unreliable than ever due to the increased uncertainty and possible time-variation in potential output brought about by the recent financial crisis.

The unreliability of output-gap measures is not the only reason why a central bank may fail to take timely action, irrespective of its willingness to act pre-emptively. A too-narrow focus on inflation forecasts may be equally hazardous.

On one hand, inflationary pressures might remain latent for years owing to compensation by other forces, especially if the central bank gives strong weight to measures of core inflation. For instance, globalisation may exert a disinflationary impact on consumer price inflation through a rising share of imports from low-cost countries. A focus on core inflation may fail to detect the inflationary pressure associated with an increase in the prices of oil-related items and non-energy commodities owing to rising demand from the fast growing non-OECD economies. [9]

On the other hand, the relationship between financial imbalances and inflation depends crucially on the forces driving asset prices. Take for example the second half of the 1990s. At the time the availability of new technologies and the widespread use of the internet were expected to lift the potential growth of the economy. The possibility that the dream of a “new economy” could become true was surrounded by high uncertainty. However, it seemed rational to invest massively in the new technologies so as to be ready to fully reap the benefits, if (and when) the new era arrived. This over-accumulation of capital can lead to a rise in labour productivity. Due to stickiness in nominal wages, labour compensation might lag the pick-up in productivity. Thus, business profits might boom, which in turn might feed back into a higher rate of investment and even bigger boost in productivity. These developments may end up in long-lasting subdued inflationary pressure, or even declining inflation for an extended period of time. Disinflationary pressure is indeed the result found in a formal analysis of this type of situation made in a recent research paper at the ECB. [10] The paper shows that if the central bank concentrates exclusively on inflation forecasts as a summary statistic for the state of the economy, it will tend to adopt an accommodative stance. This occurs because the central bank, expecting a decrease in inflation, will cut the policy rate to keep inflation on target. This accommodative policy can trigger an asset price and credit boom that inflates the original economic expansion. Eventually, it may turn out that the expectations of a new era, which triggered the over-accumulation of capital, do not come true. The revision of these beliefs can in turn lead to an asset price bust and to recession. Clearly, the boom and bust would have been much smaller had the central bank followed a different monetary policy, based on enlarging its information set to include credit developments.

3. A more explicit role for financial conditions in monetary policy

So far I have discussed the pre-crisis consensus view on monetary policy and asset prices from a general perspective. The events of the past two years have already generated far-reaching reflections on this issue. [11] Let me mention three avenues.

First, the crisis has clearly demonstrated that the economic costs of the unravelling of imbalances can be overwhelming, notwithstanding extraordinary policy action - involving both monetary and fiscal policies. Recent empirical research has explored more systematically the role of monetary policy in shaping the duration and depth of recessions. [12] When no distinction is made with regard to the nature of the downturn, expansionary monetary policy is found to be consistently associated with shorter recessions. However, when considering recessions that occur in combination with financial crises, monetary policy does not have a consistent effect on the duration of recessions. These results undermine confidence in one of the arguments buttressing the pre-crisis consensus view, namely that monetary policy can forestall the negative effects of the unravelling of financial imbalances.

Second, the crisis has highlighted the fact that asset price misalignments can have different consequences depending on the specific market in which they arise. It may well be true that, in periods of booms in asset prices, expected capital gains are so large that interest rate movements of a standard magnitude would not be sufficient to alter investor decisions. The origins of the recent financial crisis, however, are not in equity prices, but rather related to real estate and to the abnormal growth in securitised credit backed by residential or commercial properties. Leveraged financial intermediaries have also played an important role in the recent financial crisis.

In this context, recent research has highlighted the fact that even small changes in policy rates can have non-negligible implications for financial institutions, which tend to systematically finance illiquid long-term assets through short-term borrowing. Even small changes in short-term interest rates can affect their profitability, forcing them to close some leveraged positions and, potentially, to partially correct any financial imbalances fuelled by such leveraged positions. [13]

Third, the recent financial crisis has confirmed that a central bank’s inability to identify in real time the precise mechanisms through which financial imbalances evolve and to anticipate the exact timing of their unwinding does not mean it is unable to identify the build-up of imbalances. In the run up to the crisis several policy makers did identify the under-pricing of risk as a major source of concern. In this context, let me mention that recent research – including research conducted at the ECB – has reviewed more systematically the implications for monetary policy of a more explicit role for financial factors in macroeconomic models. [14] This stream of research is still under development, but it does account for an endogenous interaction between macroeconomic conditions and the demand for and supply of credit.

The main policy implication of this research continues to be that monetary policy should pursue price stability as a primary objective. At the same time, however, it is acknowledged that financial imbalances can generate sizable macroeconomic costs at times of crisis, when they can produce undesirable economic fluctuations. This justifies a very close monitoring of financial conditions. These new models also show that financial conditions have an impact on the notion of a natural rate of interest – the theoretical interest rate level which, if implemented by the central bank, would ensure that price stability is maintained. Of course, the practical relevance of this notion is limited, since it is extremely hard to estimate it accurately and robustly. Nevertheless, developments in financial conditions should be taken into account when making such estimates.

All in all, both the experience of the past two years and recent developments in the literature appear to support the view that the use of financial indicators in the context of a broader analysis of monetary and financial conditions in the economy is beneficial.

4. The ECB approach

The ECB strategy acknowledges that financial imbalances and unsustainable asset price developments do represent threats to price stability when taking a medium-term perspective. Given that our mandate requires the maintenance of price stability on an ongoing and continuous basis, rather than at any specific arbitrary horizon, the accumulation of unsustainable financial imbalances is a reason for concern, even if it only poses a threat to price stability over the longer term.

At the same time, the ECB strategy can help to identify financial imbalances in the context of its “monetary analysis”, in which monetary and credit aggregates are monitored, together with a large set of other financial indicators. One aspect of our monetary analysis is the identification of low-frequency trends in money and credit growth. This medium to long-term focus is an implicit way to protect against excessive money, credit and asset price growth in our interest rate decisions. The focus of the ECB monetary analysis on low-frequency trends is also consistent with the fact that over a long time horizon, price stability and financial stability complement and reinforce each other. Financial imbalances, leading to excess credit growth, high leverage, loose credit standards, booming asset prices and under-pricing of risk, create the conditions for abrupt market corrections, which also endanger the maintenance of price stability.

Recognising the importance of monitoring developments in money, credit, and asset prices, does not mean neglecting the difficulties associated with their interpretation, particularly in periods of rapid financial innovation. Moreover, there is always a risk of reacting inappropriately to unusual developments, when these are instead in line with fundamentals. However, most policy decisions are confronted with similar informational problems and require a difficult evaluation of the statistical evidence.

While monetary and financial conditions are explicitly part of the analysis of the risks to price stability at the ECB, such policy is not a panacea, nor a certain means to ensure that financial crises never arise. There are limitations to what monetary policy alone can achieve. Excessive risk and pro-cyclicality in the financial system can also result from factors other than sustained credit growth and high leverage. Hence, they require policy actions that can address the underlying causes of these factors. Supervisory and regulatory instruments are particularly well suited to preventing excessive risk-taking and the accumulation of financial imbalances.

In this respect, the creation of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) should contribute to foster financial stability. The ESRB was proposed following the setting up of the de Larosière Group in February 2009, and its establishment was agreed by the Ecofin Council in June 2009. The main tasks of the ESRB will be to monitor the stability of EU financial system, to issue warnings when the assessment of risks are deemed to be significant, and to suggest, when appropriate, policy recommendations. Close cooperation with national EU supervisory authorities and with global institutions (such as the IMF and the Financial Stability Board) should help this new institution and the central banks represented on the ESRB to deal with the challenges posed by increasingly interconnected national financial systems.

Conclusions

Let me conclude. The recent financial crisis has re-opened the debate on the relationship between monetary policy and asset prices. At the heart of that debate are questions like: Is price stability too narrow an objective for monetary policy? Should monetary policy ‘lean against the wind’, in order to avoid asset price bubbles?

I would answer these questions in two ways.

First, a monetary policy which has price stability as its primary objective is a necessary condition for avoiding asset price bubbles and promoting financial stability. With the benefit of hindsight, it seems that some of the financial imbalances which built up prior to the crisis resulted from monetary policies which were not fully in line with the objective of price stability. Either the policies were also pursuing other goals, such as supporting economic activity and employment, or they were not focusing on the appropriate indicators of inflationary pressures, attaching, for instance, too much importance to output gaps and too little to monetary and credit developments. The first steps to take are to put monetary policy back on track – so that it focuses primarily on price stability – and to improve the underlying analytical framework. In particular, it’s essential to include monetary and financial variables in the information available to central banks. They can provide the signal that the monetary policy stance needs to be tighter well before the business cycle reaches its peak, in order to ensure price stability over the medium term.

Second, a monetary policy which is appropriate for price stability might not suffice to ensure financial stability. Indeed, given that asset prices react more rapidly than other prices, they may overshoot their long term equilibrium value and have undesirable effects on the financial system. If this were to happen, should monetary policy react, even if price stability is not at risk? In other words, should interest rates be raised even if, taking into account all possible indicators, price stability is not endangered but there are risks of an asset price bubble building up?

I personally think that a case has not yet been made for such a course of action. It would imply that monetary policy follows two objectives with only one instrument, i.e. the policy interest rate. The central bank also has at its disposal the operational framework through which it injects liquidity into the system. Under certain circumstances such instruments can be used to foster financial stability, as has been done recently. When financial turbulence occurred, a modification of certain features of the main refinancing operations, for instance, through fixed-rate tender procedures with full allotment or by enlarging the collateral basis, helped to counteract financial instability. However, such action may not be very effective in symmetrical situations, in trying to counteract asset price bubbles. Evidently, other instruments are needed and they belong more to the realm of macro prudential supervision. Unless central banks are explicitly equipped with the appropriate macro-prudential supervisory instruments, they cannot be considered responsible for financial stability. In any case, providing such instruments to central banks should not be considered as a substitute for conducting a sound monetary policy unequivocally committed to the primary objective of maintaining price stability.

Thank you for your attention.

References

Adalid, R. and C. Detken (2007), “Liquidity shocks and asset price boom/bust cycles”, ECB Working Paper No 732.

Adrian, T. and H.S. Shin (2008), “Liquidity, Monetary Policy and Financial Cycles”, Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, January.

Alessi, L. and C. Detken (2009), “‘Real time’ early warning indicators for costly asset price boom/bust cycles: a role for global liquidity”, ECB Working Paper No 1039.

Bernanke, B.S. and M. Gertler (1999), “Monetary Policy and Asset Price Volatility”, New challenges for monetary policy, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 77-128.

Borio, C. and P. Lowe (2002), “Asset prices, financial and monetary stability: exploring the nexus”, BIS Working Papers No 114.

Borio, C. and M. Drehmann (2008), “Towards an operational framework for financial stability: ‘fuzzy’ measurement and its consequences”, BIS Working Papers No 284.

Borio, C. and W. White (2003), “Whither monetary and financial stability? theimplications of evolving policy regimes”, BIS Working Papers No 147.

Cecchetti, S., H. Genberg, J. Lipsky and S. Wadhwani (2000), “Asset prices and central bank policy: What to do about it?”, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 2.

Christiano, L., R. Motto and M. Rostagno (2003), “The Great Depression and the Friedman-Schwartz Hypothesis”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35(6), pp. 1119-1197.

Christiano, L., R. Motto and M. Rostagno (2008), “Monetary Policy and Stock Market Boom-Bust Cycles”, ECB Working Paper No 955.

Cúrdia, V. and M. Woodford (2008), “Credit frictions and optimal monetary policy”, NBB Working Paper 146.

De Fiore, F. and O. Tristani (2008), “Credit and the natural rate of interest”, ECB Working Paper No 889, April.

De Fiore F. and O. Tristani (2009), “Optimal monetary policy in a model of the credit channel”, ECB Working Paper No 1043, April.

De Fiore, F., O. Tristani and P. Teles (2009), “Monetary Policy and the Financing of Firms”, manuscript, European Central Bank.

Detken, C. and F. Smets (2004), “Asset price booms and monetary policy”, in H. Siebert (ed.), Macroeconomic policies in the world economy, Springer.

ECB (2005), “Asset price bubbles and monetary policy”, Monthly Bulletin, April, pp. 47-60.

Faia, E. (2008), “Optimal Monetary Policy with Credit Augmented Liquidity Cycles”, mimeo, Goethe University Frankfurt.

Faia, E. and T. Monacelli (2007), “Optimal Interest Rate Rules, Asset Prices and Credit Frictions”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 31-10, pp. 3228-3254.

Gerdesmeier, D., B. Roffia and H-E. Reimers (2009), “Asset price misalignments and the role of money and credit”, ECB Working Paper No 1068.

Gertler, M. and P. Karadi (2009), “A Model of Unconventional Monetary Policy”, mimeo, New York University.

International Monetary Fund (2009), “From Recession to Recovery: How Soon and How Strong?”, World Economic Outlook, Ch. 3, Washington DC.

Kohn, D.L. (2007), “Monetary policy and asset prices”, Monetary Policy: A Journey from Theory to Practice, ECB, pp. 43-51.

Kohn, D.L. (2008), “Monetary Policy and Asset Prices Revisited”, speech at the Cato Institute’s Twenty-sixth Annual Monetary Policy Conference.

Lombardo, G. and P. McAdam (2009), “Financial Market Frictions in a Small Open Economy for the Euro Area”, mimeo, ECB.

Ravenna, F. and C. Walsh (2006), “Optimal Monetary Policy with the Cost Channel”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 53, pp. 199-216.

Trichet, J.C. (2009), “Credible alertness revisited”, intervention at the symposium on “Financial stability and macroeconomic policy” sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 22 August.

White, W. (2008), “Should Monetary Policy Lean Against Credit Bubbles or Clean Up Afterwards?”, mimeo.

Woodford, M. (2003), Interest and prices: Foundations of a theory of monetary policy, Princeton University Press.

-

[1] I would like to thank G. Carboni, F. de Fiore, O. Tristani and L. Cappiello for their contributions and R. Motto and M. Rostagno for their comments. I remain solely responsible for the opinions expressed.

-

[2] See, for instance, C.E. Walsh (2009), “Using Monetary Policy to Stabilize Economic Activity”, paper presented at the 2009 Jackson Hole Conference. In my remarks I will focus on the elements of the “consensus view” that are directly relevant to the relationship between monetary policy and asset prices.

-

[3] See, for example, Bernanke and Gertler (1999), Cecchetti et al. (2000), Borio and White (2003), ECB (2005), and Kohn (2006).

-

[4] See, for example, Borio and Zhu (2008), “Capital Regulation, Risk-taking and Monetary Policy: a Missing Link in the Transmission Mechanism?”, BIS Working Paper No 268.

-

[5] L. von Mises (1996), Human Action, 4th revised edition, Fox & Wilkes, San Francisco, p. 576.

-

[6] J. Taylor (2007), “Housing and Monetary Policy”, paper presented at the 2007 Jackson Hole Conference.

-

[7] See World Economic Outlook (2009), “Chapter 3: Lessons for Monetary Policy from Asset Price Fluctuations”, October.

-

[8] See, for example, A. Orphanides (2001), “Monetary Policy Rules Based on Real-Time Data”, American Economic Review, vol. 91(4), 964-985.

-

[9] See, for example, ECB (2008), “Globalisation, trade and the euro area macroeconomy”, Monthly Bulletin (January), pp. 75-88.

-

[10] L. Christiano, C. Ilut, R. Motto and M. Rostagno (2008), “Monetary policy and stock market boom-bust cycles”, ECB Working Paper No 955.

-

[11] See, for example, Kohn (2008) and Trichet (2009). See also White (2009).

-

[12] International Monetary Fund (2009).

-

[13] Adrian and Shin (2008).

-

[14] See, for example, Christiano, Motto and Rostagno (2003 and 2006), Cúrdia and Woodford (2008), De Fiore and Tristani (2007 and 2008), De Fiore, Tristani and Teles (2009), Faia and Monacelli (2007), Faia (2008), and Gertler and Karadi (2009).

Evropská centrální banka

Generální ředitelství pro komunikaci

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Německo

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukce je povolena pouze s uvedením zdroje.

Kontakty pro média