How can the European economy succeed in an increasingly globalised world ?

Speech by Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the ECBPresident of the European Central BankAmsterdam, 15 February 2007

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a pleasure for me to be here today and share with you some thoughts on how the European Economy can succeed in an increasingly globalised world. This question is as old as globalisation itself and deeper thoughts on how economies can succeed in the presence of increased trade and integration date at least back to David Ricardo (1772-1823). As you know, on the basis of a contract between England and Portugal on trade in wine and cloth, he showed in a model containing just these two goods and the production factor labour, that trade can be beneficial for both countries even if one country has an absolute advantage in producing both goods, that is when it has a relatively lower labour input in producing both goods. Although on first sight absolutely simple, Paul Krugman praised Ricardo’s idea as ‘‘[..] truly, madly, deeply difficult [..] but also utterly true, immensely sophisticated - and extremely relevant to the modern world’’. [1] Today, more than two centuries later, we still ask how countries should position themselves to gain from trade and integration, but the focus has become a global one, with goods and services, capital and information surrounding the world at a speed none of us would have imagined only a decade ago.

For the euro area countries, the change in their economic environment has been particularly marked over the last decade: while being increasingly integrated into the global economy, they are part of the European Union that witnessed a substantial enlargement in recent years. And they are closely integrated in EMU, where now altogether 13 countries share the same currency.

Against this background, I would like to split this exposition into two major parts. First, I would like to review some stylised facts on the features of the euro area’s integration into the global economy and how this has changed over time. Second, based on how the euro area has coped so far in its increasingly globalised environment, I would then like to draw your attention to structural reforms that I consider decisive for the euro area to remain competitive and to keep pace with its main competitors worldwide.

Developments in intra-European integration

The economic and financial environment of the euro area has changed substantially during the last decades and is still changing further. We know that by moving from several currencies to a single currency many costs are reduced or in some cases even disappear. The euro has contributed to reducing trading costs both directly and indirectly by, for instance, removing exchange rate risks and the costs of currency hedging among the legacy currencies. Information costs have been reduced as well. The euro also enhances price transparency and discourages price discrimination: this helps to reduce market segmentation, while also fostering competition. Hence, the euro acts as a catalyst for the single market programme and provides a positive impetus to the euro area economy.

Many studies and analyses are now substantiating some of the important effects of the euro adoption. First and foremost, the euro area economies are becoming more interdependent, as evidenced by the significant increase in intra-euro area trade in goods witnessed since the launch of the euro. Indeed, exports and imports of goods within the euro area increased from about 26% of GDP in 1998, a year before the adoption of common currency, to around 31% in 2005. This rise in cross-border trade may be associated, to a large extent, with the introduction of the single currency and the increased price and cost transparency that it helped to foster.

A less-known feature of deepening trade is that intra-euro area trade in services has also grown in recent years. Intra-euro area exports and imports of services increased from about 5% of GDP in 1998 to around 6.5% in 2005. Trade in services should rise faster, accompanying the completion of the single market for services. This is particularly necessary in the financial area. We are perhaps already seeing the first signs of this process; during 2004-2005 the growth of the euro area’s international trade in financial services (intra euro area + extra euro area) surpassed the growth in all other sectors of services, with intra-euro area trade in financial services growing almost as rapidly as extra-euro area services trade. The other dynamic sectors on the intra-trade side were computer and information services as well as communication services.

The increasing interdependence of the euro area countries is also confirmed by the considerable growth in intra-euro area foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, which are now on par with extra-euro area FDIs accounts for about 5 percent of euro area GDP per annum. Such FDI flows accumulate over time and contribute to the reshaping of Europe as we know it. Between 1999 and 2004, intra-euro area FDI stocks grew robustly from almost 14% to around 28% of euro area GDP.

The globalisation process

The very profound structural changes in Europe take place simultaneously with the process of globalisation. Globalisation is characterizing today’s world. The internationalisation of economic life is reflected in the sharp enlargement of cross-border activities in the goods and capital markets globally. As an even greater number of companies and countries have become more involved in foreign trade of goods and services, world trade has been growing faster than global economic output, thereby, leading to a higher degree of trade openness worldwide, which increased from about 45% in 1998 to more than 55% in 2005.

The globalisation process is not limited to trade flows. Cross-border FDI has also flourished as a result of the rapid internationalisation of production. Moreover, not only the amount of investments, but also the structure of world FDI has been affected by globalisation and the worldwide division of labour. The motives of production cost savings and new market access resulted in a redistribution of FDI flows and stocks in favour of developing countries, mainly situated in Asia. At the same time, one should not forget the role played by the global integration of financial markets, which gave access to international capital for many developing countries, increasing their involvement in the global economy even more.

Integration of the euro area into the global economy

Taking into account these broad world globalisation trends, one could naturally pose the question “Has the process of intra-European integration advanced in isolation of world trends?”. The answer is a resounding “No”. In fact, exports and imports in goods with trading partners outside the euro area rose from about 24% of GDP in 1998 to almost 30% of GDP in 2005, reflecting an even higher increase than for intra-euro area trade in the same period. This is mainly due to the more sustained growth in world GDP, an increase in global trade integration and a very sizeable increase of euro area trade with China, emerging Asia, and the new EU Member States that joined the Union in May 2004. For example, the share of China and the new EU Member States in extra-euro area trade increased from 11.7% in 1998 to 17.2% in 2005. Also the increase in extra-euro area trade in services was remarkable: from about 7.5% of GDP in 1998 to around 9.5% in 2005. Turning to extra-euro area outward FDI stocks [2], their growth in the same period proved equally remarkable rising from 21% to 34% of euro area GDP; albeit the rise was somewhat less rapid than the one observed for intra-euro area FDI. The financial openness of euro area is also confirmed by ratios of external assets and liabilities to GDP (respectively 135% and 145% in 2005) [3], which exceed those of US.

Taken together, these stylised facts underscore that euro area countries are fully involved in the globalisation process so that we can easily conclude that we are not witnessing the creation of a “fortress Euro area”!

Change in factor intensity of euro area exports

Globalisation fundamentally changes world patterns of production and trade, providing a lot of opportunities as well as challenges for the euro area countries. The crucial question therefore is how the euro area tackles these challenges and opportunities. In other words, the euro area global competitiveness and trade specialisation in comparison with that of its trading partners is of great importance.

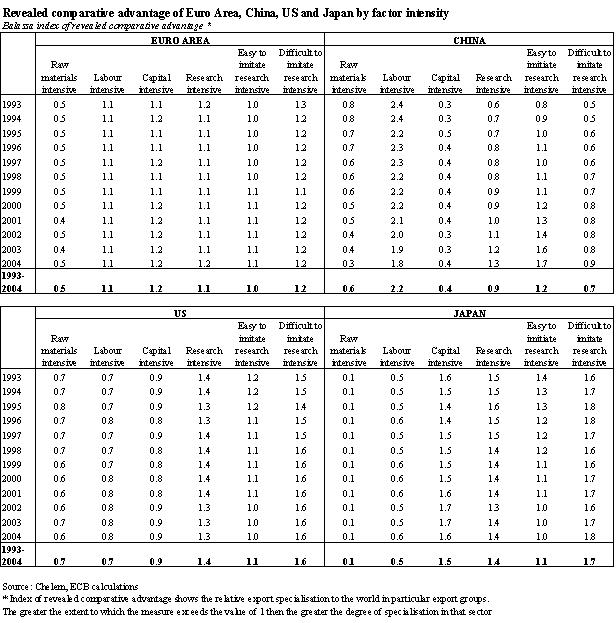

The results of our latest research on the comparative advantage according to factor intensity show that, between 1993 and 2004, the export specialisation of euro area exporters seems quite broad. While the euro area does not specialise in raw materials-intensive exports, its comparative advantage lies predominantly in capital-, research-intensive, as well as labour intensive categories of exports. The specialisation in the latter category does not seem to be fully in line with the capital-labour ratio of the euro area, which is much higher than in emerging economies. Partly, this reflects the export specialisation of some euro area countries in lower-tech sectors such as textiles and paper.

By contrast, the United States and Japan have a strong specialisation in research-intensive exports, in line with their relatively large share of R&D spending in GDP. In addition to this, Japan is also specialised in predominantly capital-intensive goods, reflecting its large capital-labour ratio. Unsurprisingly, China, but also other emerging Asia and the central and eastern European countries (CEEC) have a concentration in exporting labour-intensive goods.

The trade integration of the emerging countries should a priori have led to large changes through time in comparative advantages and thus specialisation across countries in recent years. However, it is rather striking that the euro area’s export specialisation tends to change rather slowly over time in comparison to competitors, and we still see a relatively high specialisation in labour-intensive goods for the euro area despite the increasing trade integration of the CEECs and emerging Asia. Moreover, euro area specialisation in research-intensive products, which is, as we have seen, not as strong when compared to Japan and the United States, and has not increased much over time. [4]

At the same time China’s specialisation in labour-intensive goods has actually fallen over time, while its specialisation in research intensive goods has sharply increased and is now larger than that of the euro area. Partly this is explained by imitation of technologies, or the assembly of research-intensive products in China, rather than their full development and manufacture. Nevertheless, China is rapidly moving up the technological ladder, possibly suggesting more competitive pressure originating from the developed economies down the road.

How has the euro area coped so far?

How has the euro area succeeded in its increasingly globalised economic environment over the last decade? Looking back I would say that the euro area is able to make globalisation a success for its citizens. Trade and investment performance have contributed to GDP per capita growth, with GDP per capita growth standing on average at 1.84% between 1998 and 2006, that is the eight year-period since the start of Stage Three of EMU. [5] Furthermore, between 1998 and 2006, the euro area employment rate rose by 5.4 percentage points to 64.4% in 2006 [6], with females and older workers aged 55-64 even witnessing an increase in their employment rates by 8 percentage points. At the same time, the euro area unemployment rate declined by 3 percentage points to 8.3% in 2006 [7] and estimates of the non-accelerating inflationary rate of unemployment (NAIRU) by international institutions point to a downward trend in structural unemployment.

Interestingly, given the widespread fears that particularly low skilled persons in the industrialised countries would loose most from globalisation, in the euro area, by skill level, the unemployment rate of low-skilled persons declined strongest over the last decade. While persons with tertiary education witnessed a decline in their unemployment rate by 2 percentage points to 4.7% in 2006 and persons with at least secondary education a decline by 1.4 percentage points to 7.2%, the unemployment rate of persons with just below secondary education declined by 3.4 percentage points to a still high level of 9.9% in 2006. The employment gains for low-skilled workers in connection with the observed growth of the service sector over the last decade may be taken as evidence that the euro area labour force is reasonably successful in adjusting to globalisation by structural change towards services.

Despite these successes, the euro area’s capacity to adjust and to grow in the presence of globalisation is far from having achieved its full potential. Still more resources must be put at productive use. For example, GDP growth per hour worked in the euro area declined to an average of 1.2% between 1996 and 2005 down from 2.2% between 1990 and 1995, while the US doubled its average growth in GDP per hour worked from 1.2% to 2.4% over the same periods. [8] At the same time, employment is still low and unemployment high in comparison with other main competitors. For example, the US met the EU’s target of 70% for the employment rate of those aged 15 to 64 by 2010 already in 1995 and the US unemployment rate amounted to just 4.6% in 2006. [9] Furthermore, the share of long-term unemployed in the euro area stood at an enormously high level of 46.8% in 2006, implying that almost every second person in the euro area labour force has been unemployed for more than a year. At the same time, although following a downward trend, the youth unemployment rate in the euro area amounted to 16.2% in 2006. Thus, a large amount of human capital, which is decisive for maintaining the euro area’s competitiveness, is unused and at risk of deteriorating.

The need for structural change and reforms

For a long time, we have observed that in particular Multinational Enterprises could react flexibly enough to changing market conditions in different areas of the world by sufficiently adjusting their internal division of labour across borders. Today - and this is one of the main features of globalisation that we observe - each individual has access to the world market via internet and can offer products and compare product prices. [10] It is this feature which, on the one hand, offers enormous opportunities for welfare gains but which, on the other hand, creates great challenges to competitiveness. Thus, structural reforms need to be designed such that they offer each individual the chances of gaining from its increasingly global environment. In this regard, without aiming to be exhaustive, I would like to highlight four main areas, namely market integration and product market competition, R&D and innovation, an entrepreneurial-friendly environment as well as labour market flexibility.

First, we need further steps in the liberalisation of international trade. A danger to world growth is that the current Doha trade round does not succeed. As you know, negotiations were suspended last July, but I am very pleased that there is a tentative momentum building towards renewing negotiations, which was also seen in Davos and was fully supported by the recent G7 in Essen, whose members gave a clear commitment to the Doha round of free trade talks and accepted their responsibility to ensure a successful outcome. I note that this momentum has now led to substantial moves in Geneva, with the WTO Director-General, Pascal Lamy, announcing that he is beginning to reconvene the various negotiation groups. We can only wish him success and ask political leaders, who have said they would like to see a successful conclusion to the round, to follow through their words with deeds.

Furthermore, the euro area countries will be the more equipped for the increased globalised economy the more they are able to exploit the benefits of EMU and the EU internal market. In this regard, existing impediments to the internal market for goods and services need to be removed and financial integration further fostered. Further efforts in the fields of product market deregulation and liberalisation are required to raise product market competition – at the EU and national level. As the example of the European telecommunications market shows, this would enable more efficient production structures associated with a more competitive price setting.

Second, euro area countries have to raise their innovative activity by investing more in research and development, thereby boosting productivity. In this regard, an increased level of product market competition would raise incentives to win new market shares by offering new and more innovative products, thus creating a higher demand for R&D. Against this background, the Lisbon agenda envisages that by 2010 EU countries spend on average 3% of their real GDP on R&D, including both public and private spending. With roughly 3.5% of real GDP being spent on R&D in 2005, Finland is the only country in the euro area that meets this target already. In contrast, the euro average of real GDP being spent on R&D in 2005 amounted to just 1.9%. To increase investment in R&D it is essential to foster private spending and to not rely on public spending only. Generally, economic policy has to ensure the right framework conditions for private spending on R&D as this would be best channelled towards successful investments. In this respect, necessary structural reforms include market liberalisation and deregulation, but also an adequately trained and educated workforce. There has been a remarkable catch-up in education of the younger generation compared to older generations in the euro area. In 2004, 74% of the euro area population aged 25-34 had attained at least upper secondary education, compared to 59% of those aged 45-54. [11] With ageing populations in an increasingly competitive international economic environment, education and training policies have to ensure a high quality education for the young - containing a high degree of basic knowledge but also knowledge demanded by the productive sector. And they have to ensure sufficient incentives for the life-long learning of persons that need to stay for longer in the labour force than in the past.

Third, we need to create an entrepreneurial-friendly environment with low administrative and bureaucratic costs for firms and business-starts ups. This would support the exploitation of new production possibilities, increase entrepreneurial efforts and innovative activity of firms. Together, this would raise employment and the potential growth rate of an economy. The immense importance of this issue is increasingly appreciated by the EU and European governments, with the Netherlands being one of the forerunners in the area of ‘better regulation’. A brief look at numbers shows the potential for the euro area. Following studies by the World Bank, in 2006, the average cost of starting a business with up to 50 employees in the euro area amounted to roughly 2226 USD, compared to 285 USD in the US. In 2006, it took on average 22 days to set up a business in the euro area, compared to 5 days in the US. [12] As regards administrative costs, studies gauge these costs in the EU25 to amount to 3.5% of real GDP.

Fourth, to fully exploit countries’ changing comparative advantages in producing goods and services it is essential that labour markets can adjust to the variation in their production structures. This requires the right incentives for a sufficient mobility of workers, inter alia, between jobs and regions, but also from unemployment to employment. Suitable adjustment mechanisms in the euro area also require sufficient labour mobility across borders. The new euro area member Slovenia therefore needs to be granted full access to all euro area countries’ labour markets, which is currently not the case. Furthermore, sufficient wage differentiation is needed, especially to improve employment opportunities for less skilled persons and in regions with high unemployment. Generally, wage developments need to adequately reflect developments in productivity by skill level, region and industry.

Furthermore, adjustments to the level of employment protection are required, in particular where they impede the hiring of younger and older workers. In this regard, over the last decade, the euro area countries have made progress particularly in rendering the use of temporary employment contracts more flexible. As a result, for example, the share of young people working on temporary contracts has risen to 50.3% in 2006, compared to 41% in 1996. At the same time, the level of employment protection legislation for permanent contracts has only fallen slightly since 1990. It is therefore important to reform regulation on regular contracts where it has adverse effects on hiring incentives. [13] Generally, with the ageing of the European populations, employment gains in combination with ambitious and effective structural reforms in the pension and health care sectors are the only way to render social systems sustainable in an increasingly global economy.

Implementing this necessarily non-exhaustive list of structural policy priorities should increase the euro area’s overall flexibility in an increasingly globalised world. For firms in the euro area countries, these reforms should generally lead to a greater choice of suitable investment options and open up possibilities for improved productivity, thus helping them to raise cost competitiveness. As the present strong growth and export performance of the German economy shows, which between 1999 and 2005 only witnessed limited cumulated unit labour cost increases of 2.8% compared to a euro area average of 11%, appropriate unit labour cost developments for producers are crucial for firms’ competitive position.

Conclusion

I would like to conclude by saying that granting people their share in the gains from increasing integration into the world economy requires most importantly their integration into the labour market. Given the recent gains in euro area employment, one could say that the euro area has increasingly been able to make globalisation a success for its citizens. This has been the result of a stepping up of structural reforms in the Euro area. Progress has been made but a lot remains to be done. Globalisation, together with the remarkable advances of science and technology, offers new chances and opportunities for all economies in the world and particularly for the Euro area. But we have to be fully aware of the key condition to fully reap the benefits of a phenomenon which accelerates formidably the pace of change at global level: flexibility. The more all markets of any given economy are flexible, the more this economy adapts rapidly to changes, the more it benefits from globalisation and delivers prosperity and jobs.

-

[1] See Paul Krugman (1998) ‘Ricardo’s difficult idea, www.web.mit/krugman/www/ricardo.htm.

-

[2] Stocks of FDIs outside euro area owned by euro area residents.

-

[3] Net international investment position of the euro area was -10.1% of GDP in 2005.

-

[4] To describe it in quantitative terms we can use an index of revealed comparative advantage, which shows the relative export specialisation to the world in particular export groups – the greater the extent to which the measure exceeds the value of 1 then the greater the degree of specialisation in that sector. For example, the revealed comparative advantage of the euro area in research-intensive products for the period 1993-2004 was 1.1, while it was 1.4 for both the US and Japan over the same period. See for more details Annex 1.

-

[5] Data rely on the Groningen Growth and Developments Centre. Estimate for 2006.

-

[6] Eurostat LFS data, 2nd quarter.

-

[7] Eurostat LFS data, 2nd quarter.

-

[8] Data rely on the Groningen Growth and Developments Centre.

-

[9] Annual average.

-

[10] See Denis Snower (2006) ‘Globalisation challenges for the euro area’; OeNB, Wien.

-

[11] See OECD (2006) Education at a glance, Paris. Weighted averages.

-

[12] Worldbank (2007) Doing Business 2007, Washington. GDP weighted averages, excluding Luxembourg.

-

[13] For a discussion see OECD Employment Outlook (2006) and O. Blanchard and A. Landier (2002) ‘The perverse effects of partial labour market reform: fixed term contracts in France, Economic Journal, Vol. 112, pp. 214-244.

Evropská centrální banka

Generální ředitelství pro komunikaci

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Německo

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reprodukce je povolena pouze s uvedením zdroje.

Kontakty pro média