Overview

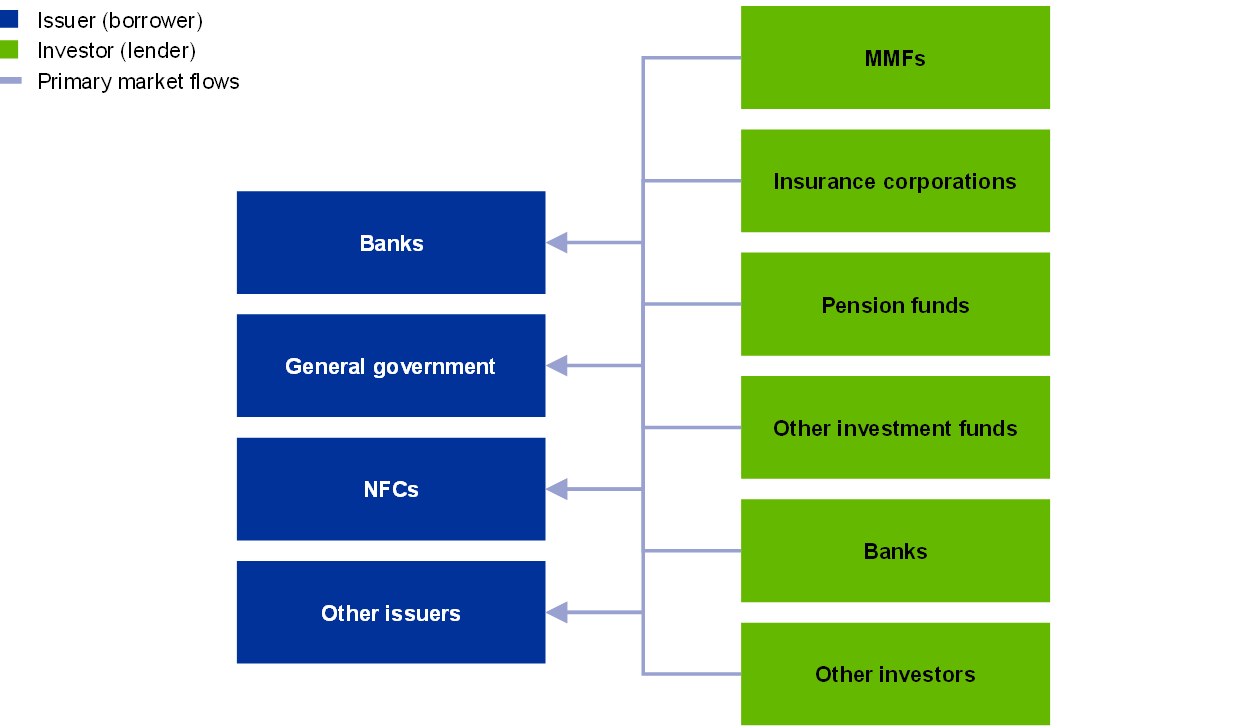

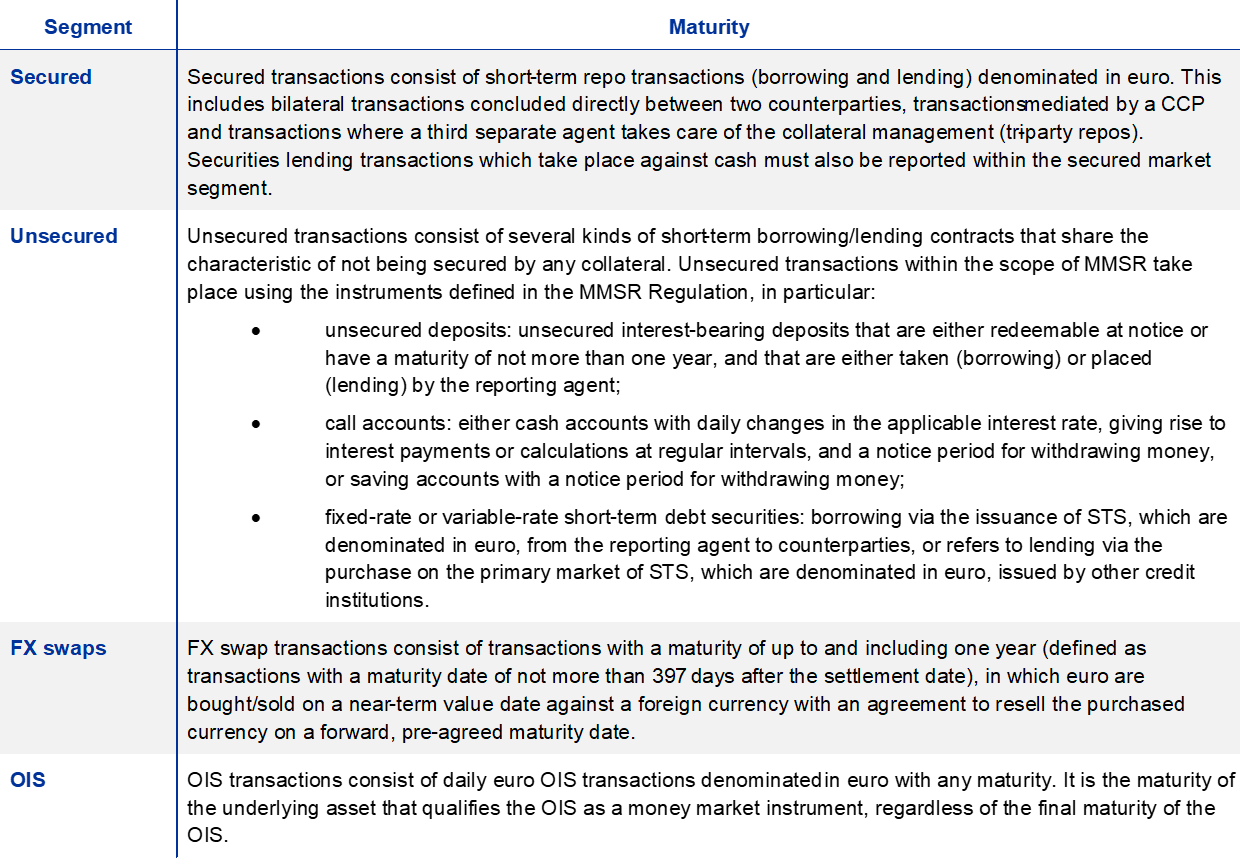

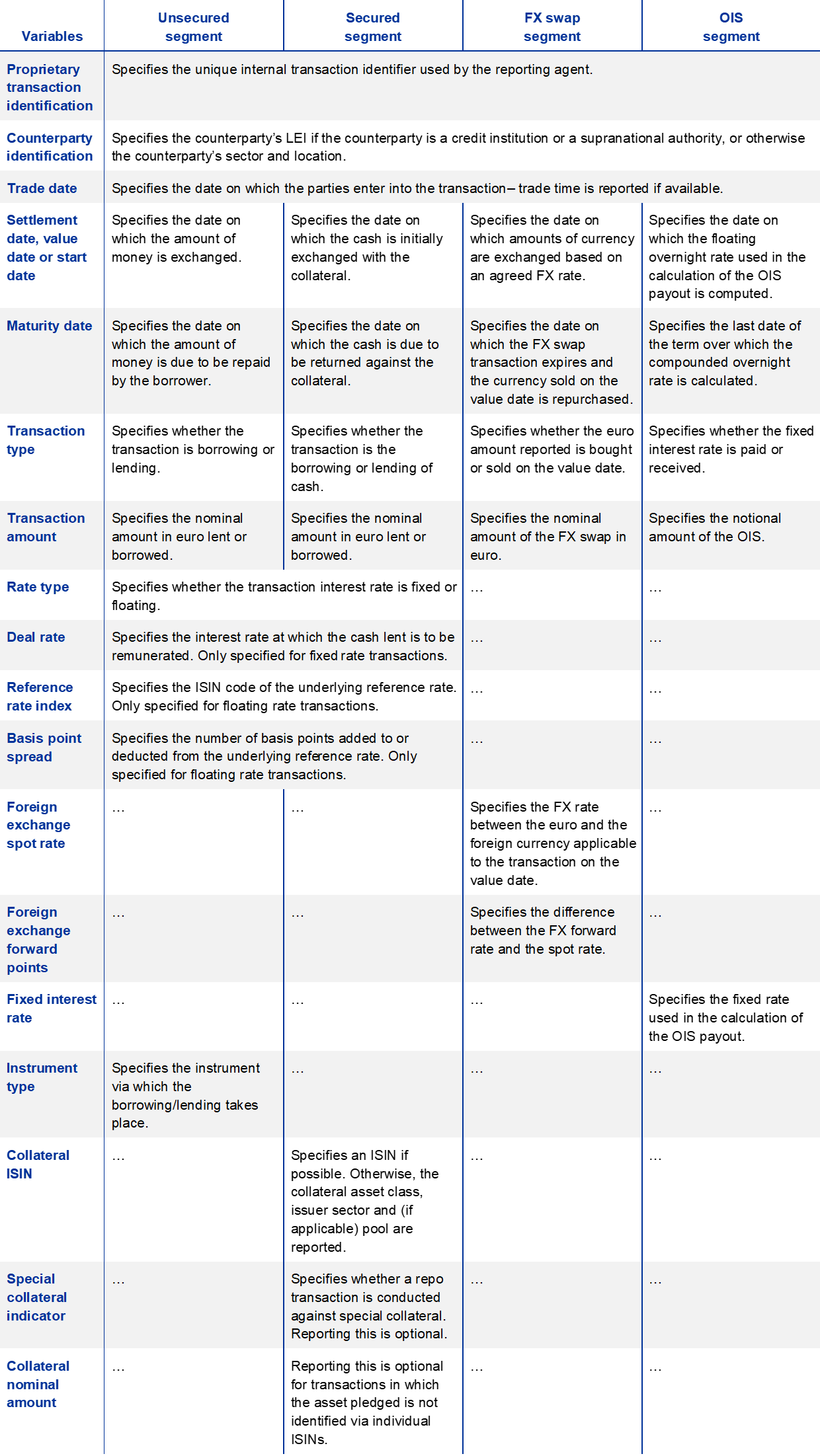

The 2020 Euro money market study is a comprehensive analysis of the functioning of euro money markets. The study covers five segments of the euro money markets: (i) secured transactions – repos and reverse repos; (ii) unsecured transactions; (iii) the issuance of short-term securities (STS); (iv) foreign exchange (FX) swaps and (v) overnight index swaps (OIS). The study describes developments in these segments between January 2019 and December 2020.

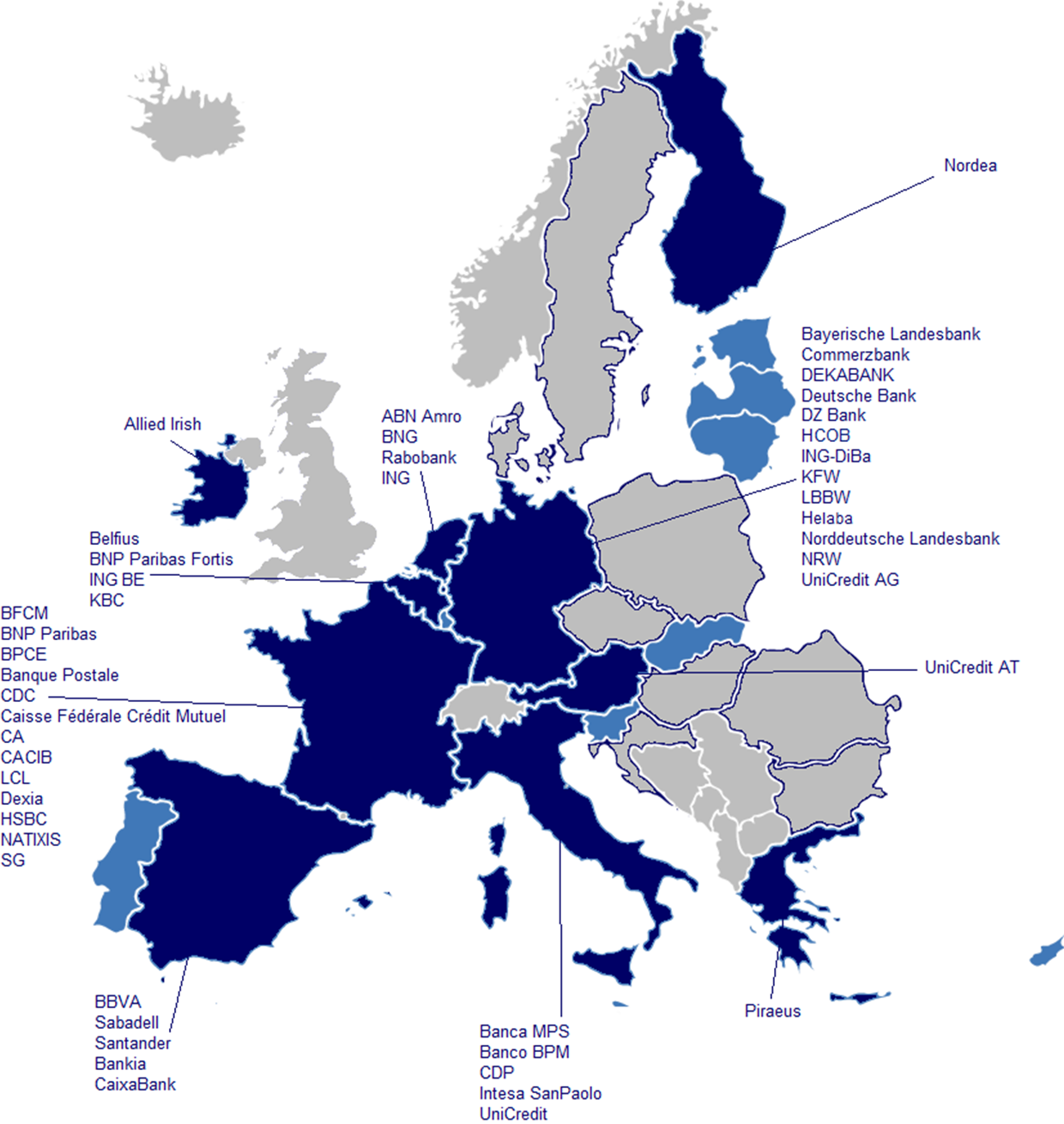

The study relies predominantly on granular data collected through the Eurosystem’s money market statistical reporting (MMSR) dataset. MMSR data have been collected since 1 July 2016 and contain details on volume, pricing, maturity and counterparty for each transaction of less than one year executed by the 48 largest euro area banks. Actual daily transactions are reported to the European Central Bank (ECB) on the subsequent business day, providing a timely insight into market developments. MMSR data cover four out of the five segments of the euro money markets. Information on the fifth segment – STS issuance – is provided by the statistics on Short-Term European Paper (STEP) and French Negotiable European Commercial Paper (NEU CP) collected by the ECB and the Banque de France respectively and complemented with commercial paper data from Dealogic.

Several events of relevance for euro money markets occurred between January 2019 and December 2020. These events included: (i) an interest rate cut of 10 basis points on the Eurosystem’s deposit facility rate (DFR), implemented on 12 September 2019; (ii) the introduction of the new unsecured euro short-term rate (€STR) developed by the ECB and published as of 2 October 2019; (iii) the implementation of the two-tier system on 30 October 2019 to exempt a part of banks’ holdings of excess reserves from being remunerated at negative rates; (iv) the outbreak of the worldwide COVID‑19 pandemic in spring 2020, followed by the ECB monetary policy measures resulting in a €2.3 trillion expansion of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet; finally, (v) the materialisation of Brexit at the end of 2020.

The main developments in euro money markets can be summarised as follows.

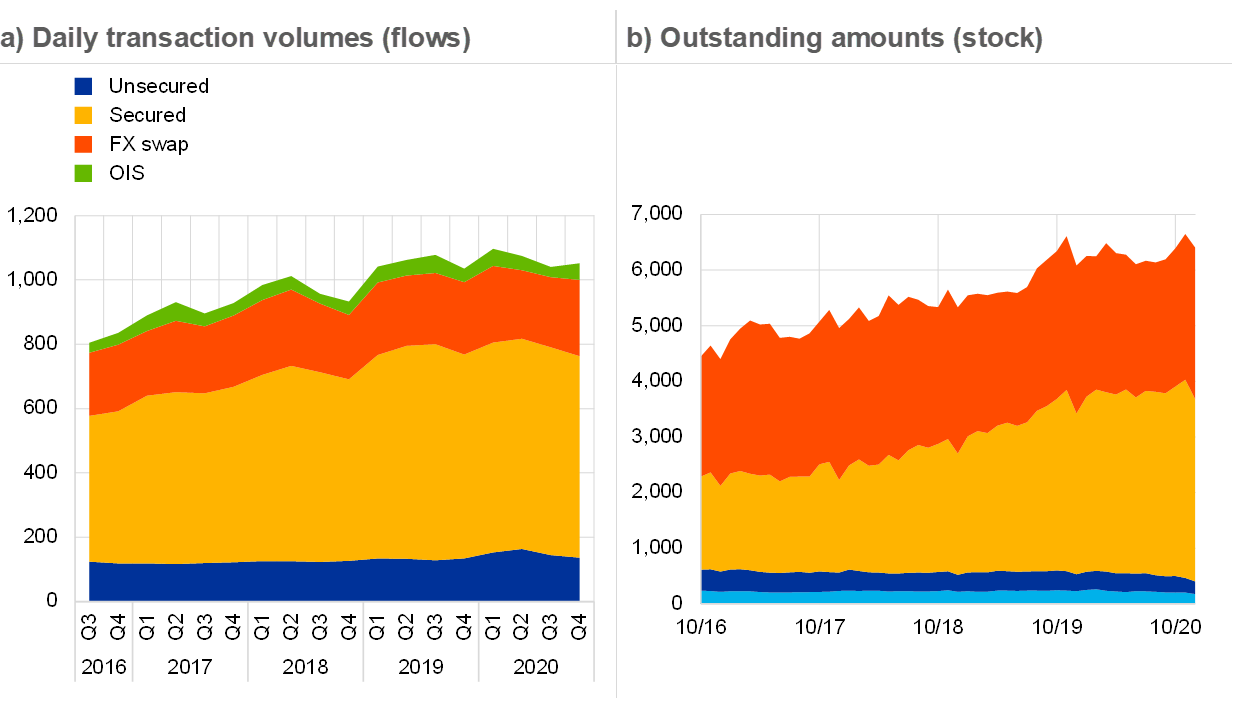

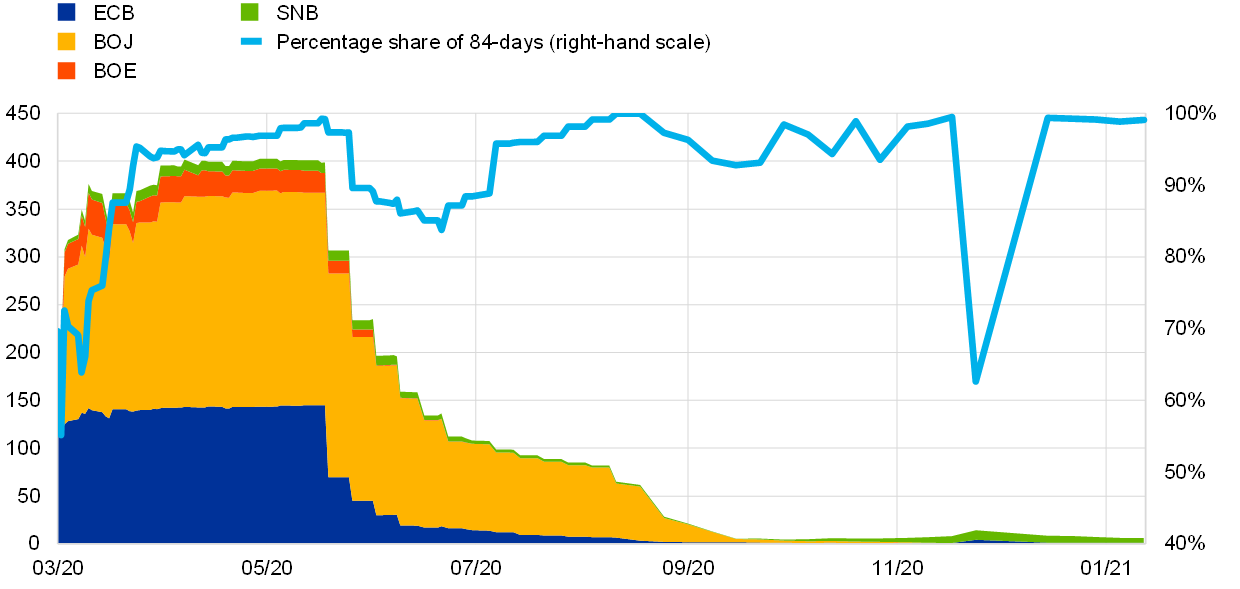

First, the secured and FX swap segments continued to dominate activity in the euro money markets. During the review period, total average daily transaction volumes (flows) for these two segments amounted to €0.9 trillion, with outstanding amounts (stock) reaching €6.0 trillion[1]. The secured segment is the largest segment of the euro money markets, accounting for 60% of total daily transaction volumes and 51% of total outstanding amounts. Traditionally, the unsecured segment has played a key role in monetary policy transmission, although the current secured segment, given its sheer size, has gained in importance for the assessment of financing conditions and thus for monetary policy implementation over the years. The second-largest segment is the FX swap segment, which represents 22% of the total flows and 43% of the total stock of the euro money markets. Following the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic in March 2020, the Eurosystem reacted decisively by providing banks a backstop in case market funding became unavailable or very costly. By the end of 2020, euro area banks had drawn a total of €1.8 trillion from the ECB’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) and temporarily covered their US dollar funding needs of USD 143.5 billion by recourse to a swap line network established by major central banks at the peak of the crisis.

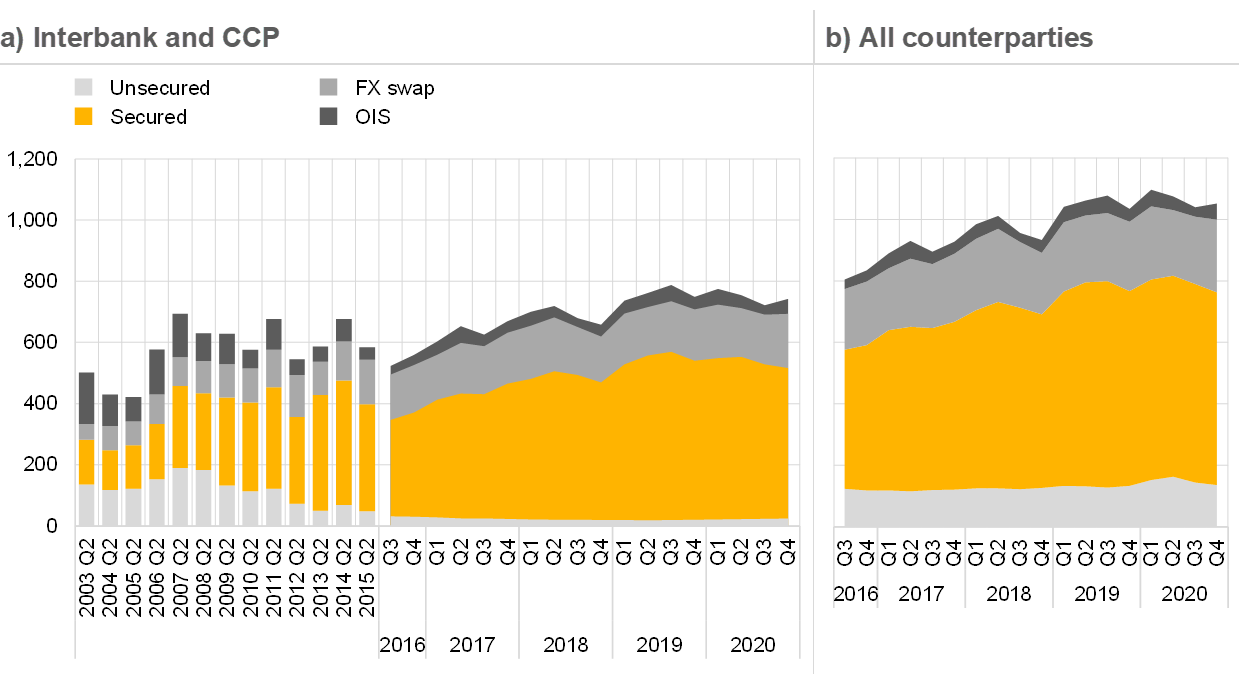

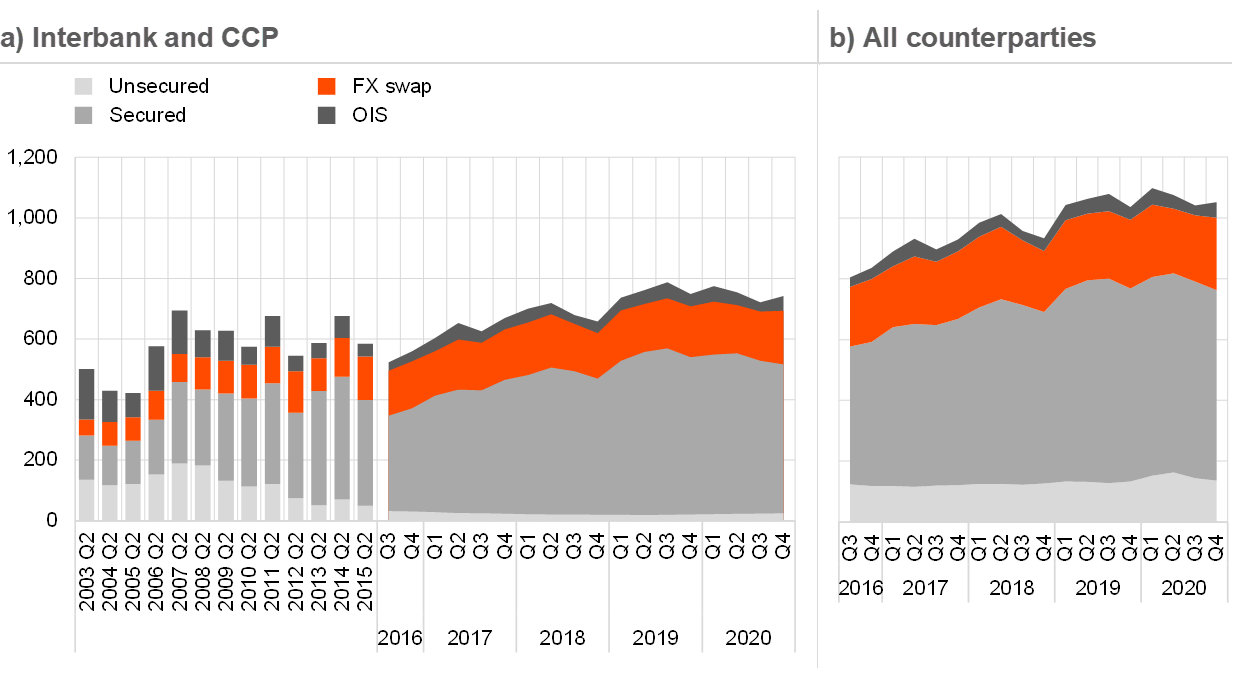

Figure A

Overview of the size of the euro money market

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations and Centralised Securities Database (CSDB) for STS series.

Notes: Panel (a) – average daily transaction volumes include all reported counterparties. The OIS segment excludes novations.

Panel (b) – outstanding amounts transform the daily transaction volumes (flows) into a stock variable based on maturity dates reported on the last day of each month. STS data refer to commercial paper and certificates of deposit with a maturity of up to 12 months and concerning only euro area issuers that are deposit-taking corporations (only in EUR).

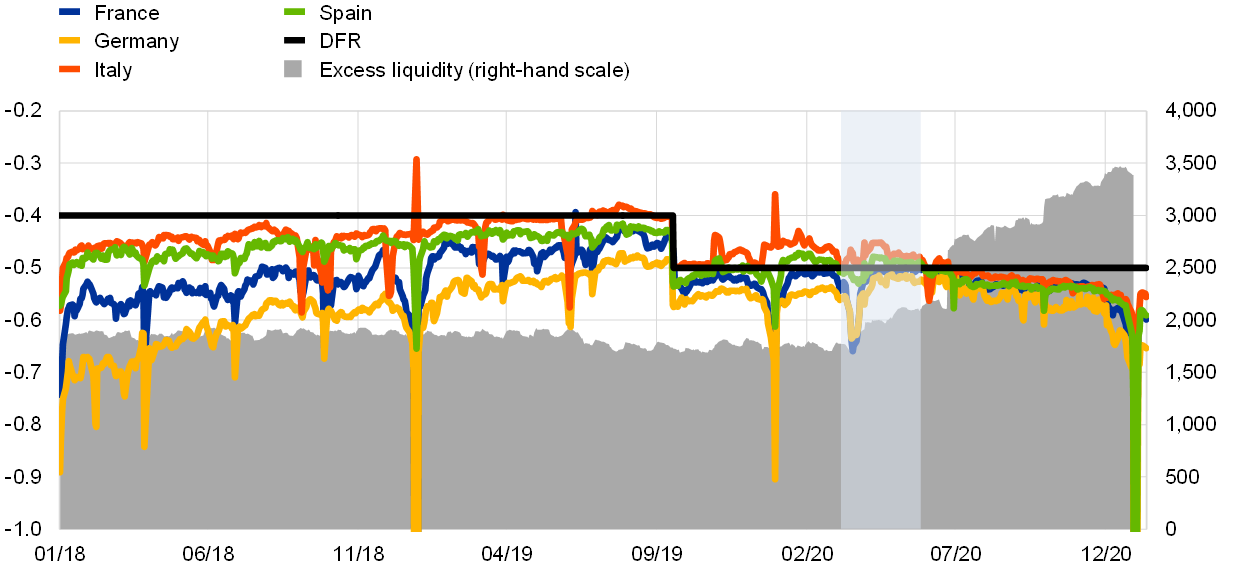

Second, the spread between repo rates of different jurisdictions narrowed significantly, facilitating the smooth transmission of monetary policy, while the spread between the repo rates and the DFR was sensitive to the availability of government bonds in the market. In 2018, repo rates diverged significantly across the euro area, with rates for core countries collateral trading well below the DFR and rates for semi-core collateral trading below but much closer to the DFR. Over the review period repo rates converged in a sustained manner. In this regard, several factors played a role. In 2019, Eurosystem asset purchases temporarily plateaued, reducing the absorption of collateral from the market; this resulted in an increase to close to the DFR in the secured rates of different jurisdictions. In the first half of 2020, the reactivation of Eurosystem net asset purchases and the start of the PEPP coincided with strong issuance activity by governments, keeping rates stable and just below the DFR. Governments’ issuance activity slowed in the second half of 2020 and repo rates embarked on a downward trend, reflecting the renewed collateral scarcity effect in a context of increasing excess liquidity. These developments highlight the sensitivity of prices in the secured segment to the availability of government bonds in the markets, as 90% of secured volumes are backed by specific collateral. To alleviate the scarcity of government bonds, the Eurosystem implemented two measures. First, it eased the collateral framework for central bank lending operations, accepting a wider use of credit claims and temporarily increasing risk tolerance. This allowed banks to pledge non-marketable securities for the purpose of Eurosystem refinancing operations such as TLTROs. Second, the Eurosystem made its asset holdings available for lending through the securities lending facility. Both APP and PEPP holdings of public sector securities can be borrowed against cash or other collateral, thus increasing the availability of high-quality liquid assets in the market.

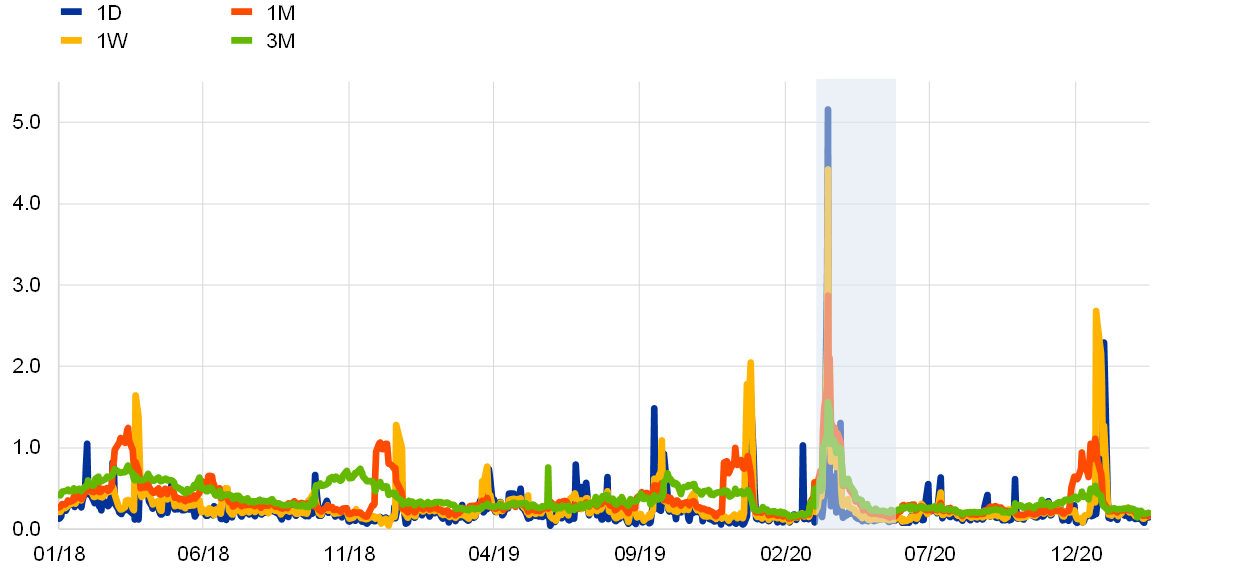

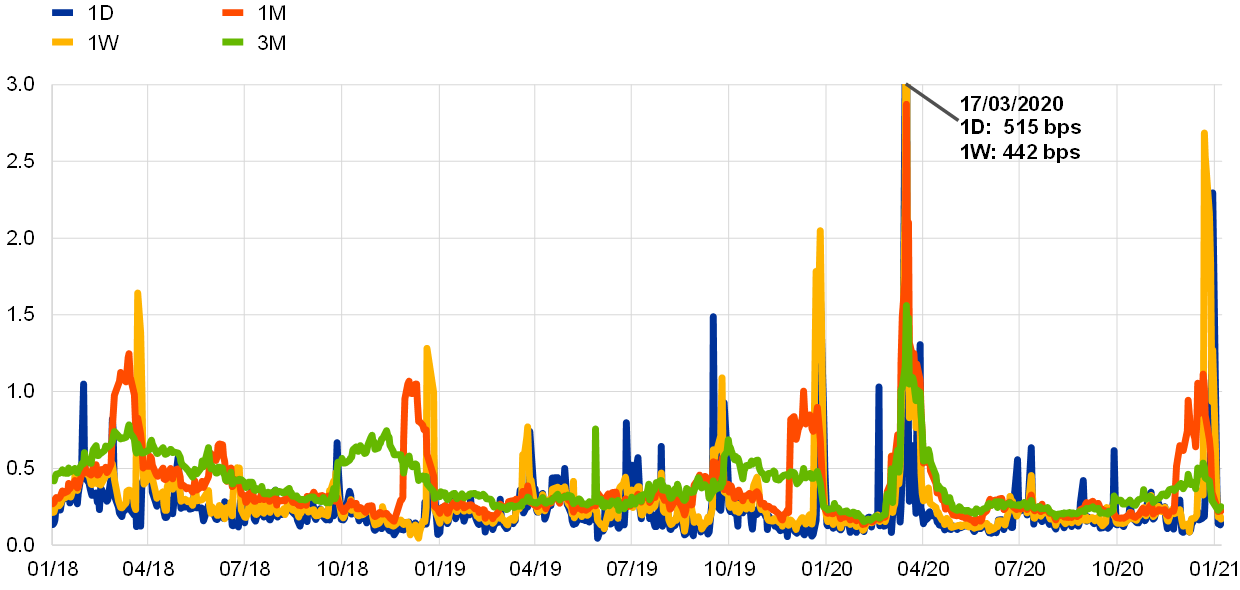

Third, the COVID‑19 pandemic revealed the contrast between the resilience of the secured segment and the distortions observed in the FX swap, STS and unsecured term segments. Owing to the high reliance on central clearing (70%), the secured segment remained robust despite the increased risk aversion throughout spring 2020. The remaining 30% of secured transactions were traded bilaterally and have also proved to be relatively resilient throughout the pandemic. Banks accounted for the largest volume of bilateral secured transactions, followed by non-banks (investment funds, MMFs and insurance companies), whose share increased notably in 2020. In contrast to the developments in the secured segment, other money market segments experienced short-lived turbulence at the peak of the pandemic. In spring 2020, there was a sharp rise in unsecured term rates, while rates for commercial paper rose quickly as demand for STS from MMFs stagnated at the peak of the pandemic. The cost of borrowing US dollars against euro in the FX swap markets also peaked at above 500 basis points at the height of uncertainty in late March 2020. Developments in the STS and FX swap markets also had spill-over effects on the unsecured EURIBOR. Eurosystem and Federal Reserve System interventions alleviated tensions in the three money market segments suffering the biggest disruptions, which returned to normal functioning in the second half of 2020. The US dollar liquidity provision by the swap line network of major central banks was particularly useful in solving distortions in the FX swap segment and the inclusion of NFC CPs in the purchases under the PEPP partially addressed tensions in the STS market, which resulted in EURIBOR falling to its lowest level ever. The liquidity providing operations of the Eurosystem (bridge LTROs, TLTROs and PELTROs) have also ensured favourable financing conditions and contributed to lowering unsecured term rates.

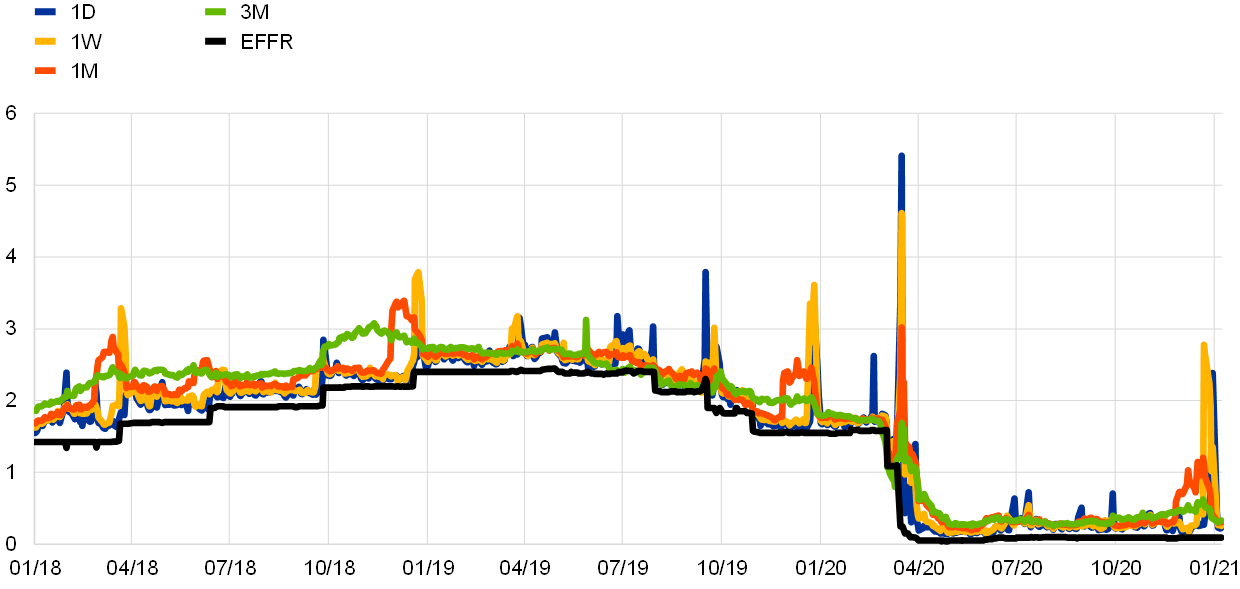

Figure B

Overview of the rates in the euro money market

(left-hand side: percentages; right-hand side: EUR billions)

a) Government repo rates by jurisdiction

b) STS rates and EURIBOR

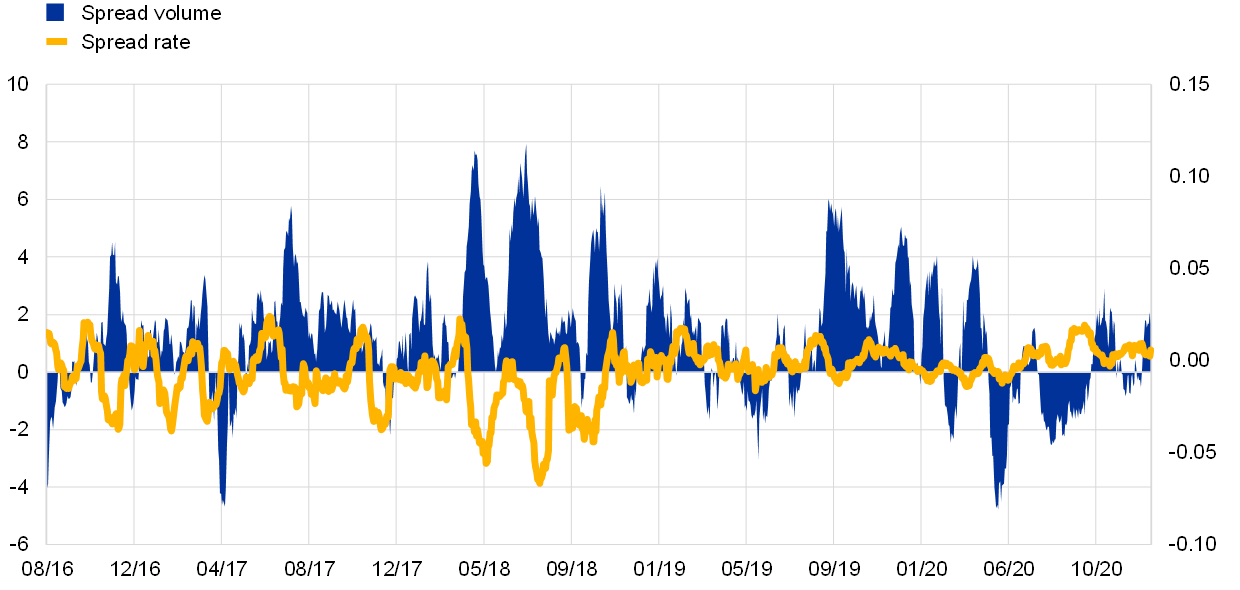

c) FX swap basis spread (EUR/USD)

Sources: Panel (a) – ECB (MMSR); Panel (b) – STS (Banque de France); Panel (c) – ECB (MMSR), Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel (a) – Volume-weighted average rate per collateral jurisdiction – only government collateral included. Plotted against settlement date. The scale is limited to ‑1%, for readability. Cut-off points: year-end 2019 DE ‑2.74% and FR ‑2.13%; year-end 2020 DE: ‑2.09%, FR: ‑1.57% and ES: ‑1.59%. Only trades with O/N, S/N and T/N maturities. The rate includes both borrowing and lending transactions. Panel (b) – “STS” stands for short term debt issuance based on NEU CP data. Panel (c) – The FX swap basis spread is calculated as the USD implied rate minus the USD OIS rate for the selected maturity. The axis is cut off at 300 basis points in the interests of readability. One-day trades combine the O/N, S/N and T/N for a selected settlement day. Confidential and missing values hidden. Blue area highlights the COVID‑19 crisis period.

1 The secured segment

The secured segment became the largest segment of the euro money market around the time of the GFC and has continued to grow ever since. During 2019 and 2020, market players continued to prefer secured trading because of its lower regulatory costs and counterparty risks compared with unsecured trading. Interbank trading of reserves now takes place mostly in the secured market.

Secured rates reflect developments in the supply of and demand for cash and collateral. During the review period, the supply of cash-reserves increased due to ECB monetary policy easing, which was reflected in the ample provision of additional liquidity. At the same time, the supply of collateral was drained due to large-scale Eurosystem additional asset purchases, while demand remained sufficiently firm to meet regulatory requirements. Both factors contributed to downward pressures on repo rates within the period under review.

In addition, there were four other notable developments in the secured segment over the period 2019‑20.

First, the euro area repo rate converged towards the DFR in 2019, after the former series of the Eurosystem’s net asset purchases had ended. However, the COVID‑19 pandemic and the Eurosystem’s policy response which included a new series of net asset purchases caused repo rates to fall below the DFR once again in 2020.

Second, the secured nature of repo transactions – the majority of which are centrally cleared – has made the euro money market more resilient to financial stress. CCPs mitigate counterparty risk and reduce reliance on costly collateral by providing netting services. During the pandemic an increase in bilateral repo trading with non-banks – mainly MMFs and insurance companies – has also been observed. Lack of confidence in secondary market liquidity of the commercial paper segment encouraged these counterparties to opt for the secured segment to increase their liquidity buffers, independently of their customer status with CCPs. They were attracted by large trading volume and stable yield curve of the secured segment during spring 2020. This confirms the trust placed in the stable nature of the repo market, which has functioned well during the COVID‑19 crisis.

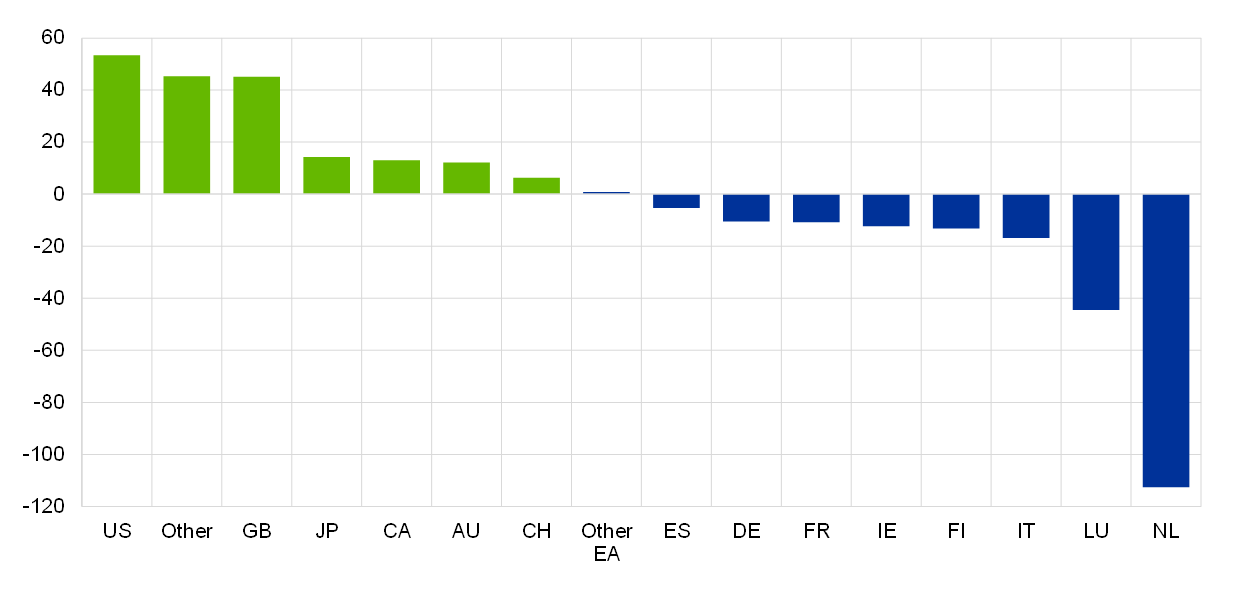

Third, there was a sizeable shift in activity from UK to euro area counterparties, coinciding with the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. The euro repo market is now mainly concentrated in the hands of players located in the euro area, which account for 90% of total trading.

Finally, the introduction on 31 October 2019 of the two-tier system for remunerating banks’ reserves incentivised reserves redistribution between banks through the repo market. The introduction of the two-tier system led to a short-lived increase in repo rates in non-core jurisdictions, although this effect did not last.

1.1 Volumes

2019‑20 trends

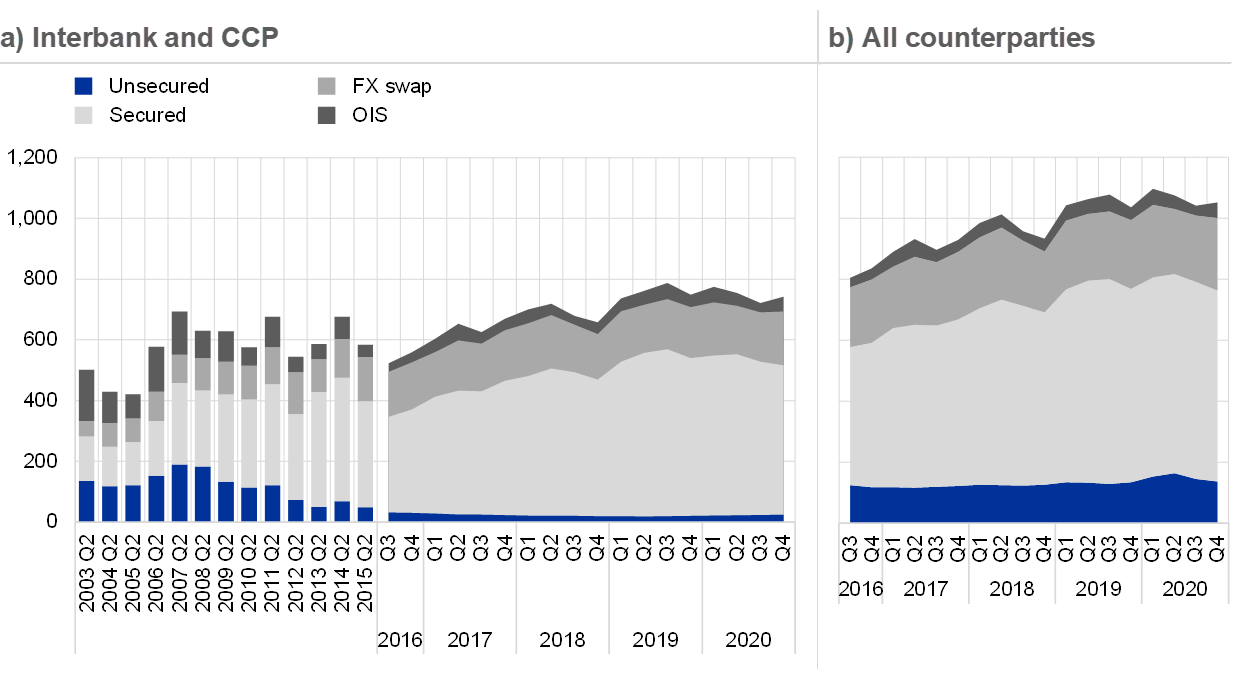

The secured segment is by far the largest segment of the euro money market, representing slightly more than two-thirds of total market turnover (see Chart 1.1). It significantly increased in size around the time of the GFC and has continued to grow ever since[2]. Counterparties favour secured trading in order to reduce regulatory costs and counterparty risk. Unsecured lending incurs higher capital charges owing to counterparty credit risk, and this is further exacerbated when the lending is to a non-euro area entity. Moreover, unsecured borrowing requires deposits to be backed by high-quality liquid assets. The liquidity risk is particularly relevant for banks borrowing for tenors below one month or accepting non-operational deposits, as these are considered less stable and hence incur higher liquidity costs under the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR).

The daily average volume of secured transactions amounted to €645 billion in the period 2019‑20. Most of these transactions – around €520 billion of daily average turnover – were conducted between euro area banks or through CCPs. In 2020, the outstanding amount of repo operations amounted to €3.3 trillion.

Chart 1.1

Market size per segment – average daily transaction volumes

(EUR billions)

Sources: Panel (a) – ECB (euro money market survey) until 2016 and ECB (MMSR) from 2016 onwards; Panel (b) – ECB (MMSR).

Notes: Panel (a) includes only interbank counterparties and CCPs; Panel (b) – includes all reported counterparties. The bars show euro money market survey data for 38 overlapping reporting agents and retropolated data for the 14 MMSR reporting agents not covered in the survey. The retropolation increases the original series by a fixed proportion representing the 14 missing reporting agents’ market share in Q3 2016 (3% for the secured segment). Two confidential datapoints have been interpolated. The OIS segment excludes novations in MMSR data.

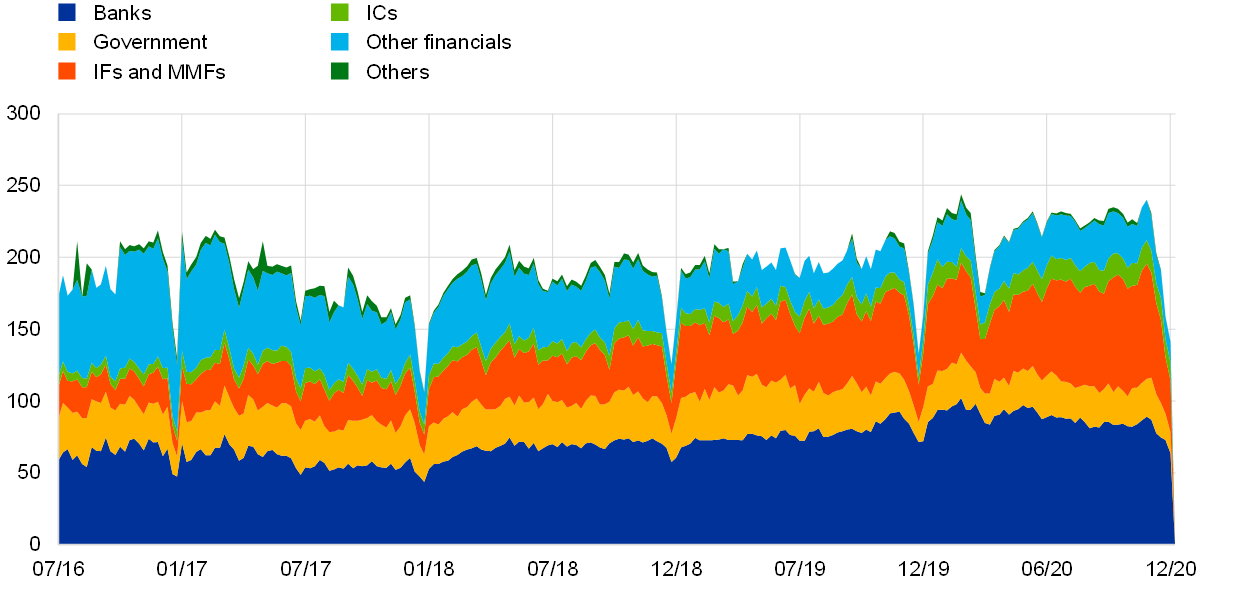

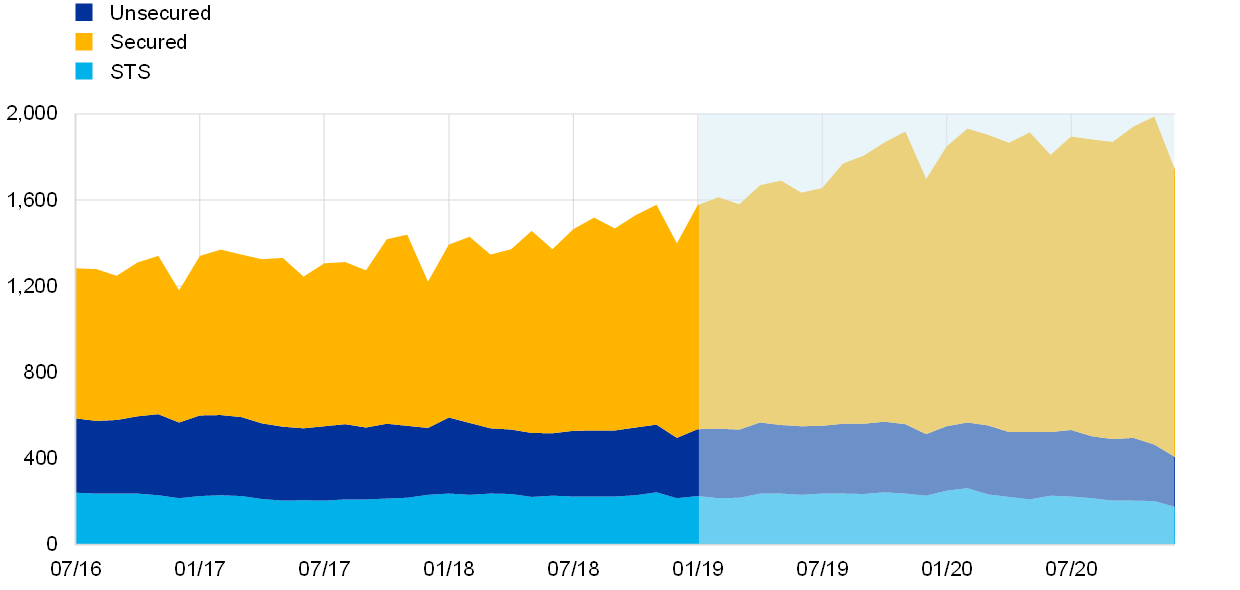

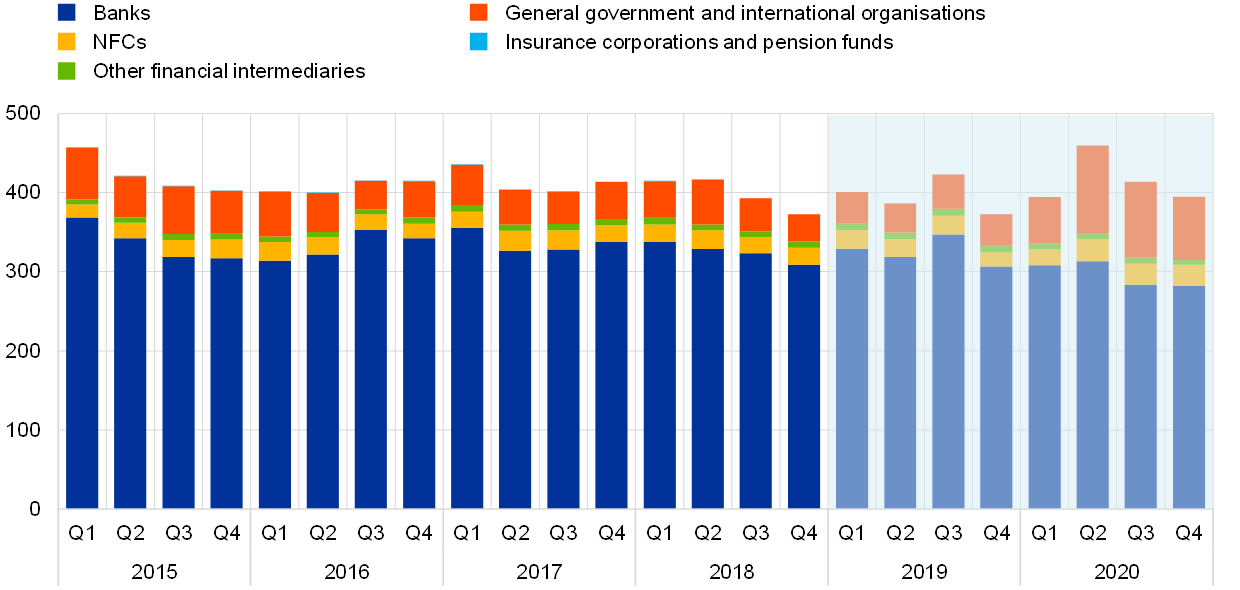

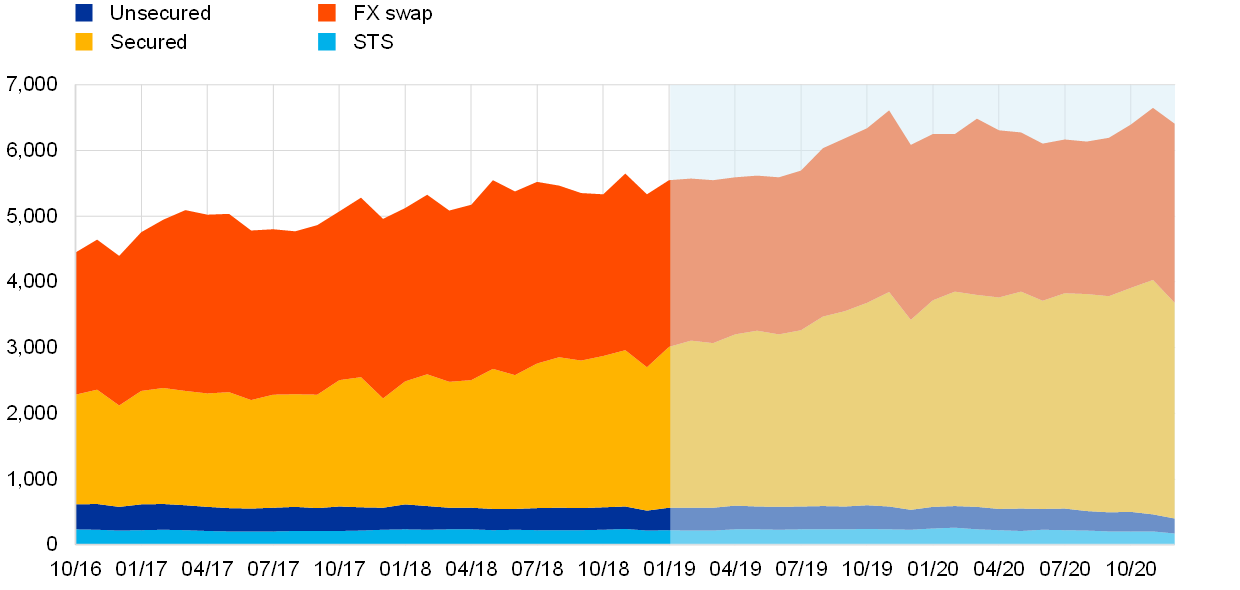

Outstanding secured volumes grew during 2019‑20 – in contrast to the other segments of the money market – even during the pandemic (see Chart 1.2). Volumes peaked in early March 2020 as participants increased their secured trading, given the uncertain environment. This rise was mostly observed for banks, MMFs and insurance companies and was concentrated in bilateral trading (i.e. not trading via a CCP). These counterparties increased their liquidity buffers during the crisis. Lack of confidence in secondary market liquidity of the commercial paper segment encouraged these counterparties to opt for the secured segment to increase their liquidity buffers, independently of their customer status with CCPs. They were attracted by large trading volume and stable yield curve of the segment during spring 2020. The repo segment has functioned well during the COVID‑19 pandemic, reflecting the safe and liquid characteristics of the secured segment. This is partly due to the large share of trades cleared through CCPs, which mitigate counterparty risk and provide netting benefits to their users. Thanks to their lower risk profile, secured transactions were much less affected by market stress in the spring of 2020 than unsecured trades. A stable bilateral yield curve was also preserved, although to a lower extent than for trading through CCP.

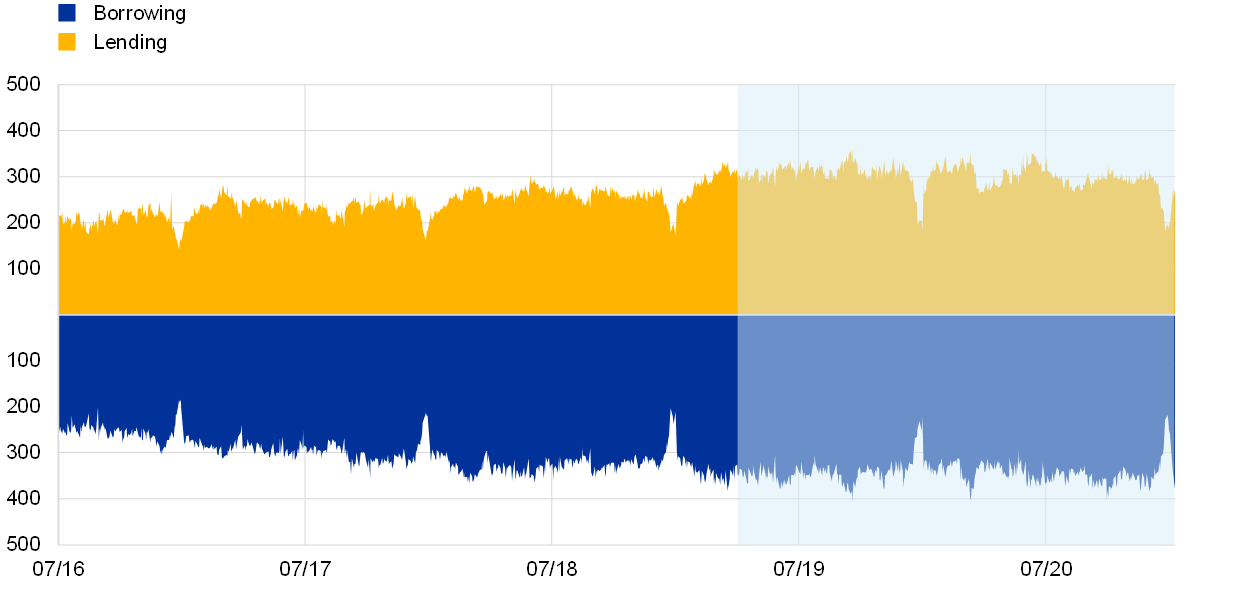

Chart 1.2

Outstanding amounts borrowed and lent by euro area banks

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR for “Unsecured” and “Secured” data), CSDB for STS data.

Notes: “Secured” and “Unsecured” data represent the outstanding amounts borrowed and lent by MMSR banks, with “Unsecured” excluding any short-term debt instruments. “STS” data refer to the outstanding amounts issued or held by euro area banks (only in EUR currency). Tenors are up to one year. The stacked areas show the amounts outstanding on the last day of each month.

Borrowing activity remained slightly above lending activity, representing around 55% of secured turnover[3] (see Chart 1.3). Market intelligence suggests that for most banks their business models determine whether they are structural cash borrowers or lenders. Some more specialised banks act as market-makers and manage “matched” repo books – i.e. broadly matching their repo borrowing and lending. However, these banks may also skew their activities slightly towards borrowing or lending, depending on their needs.

Chart 1.3

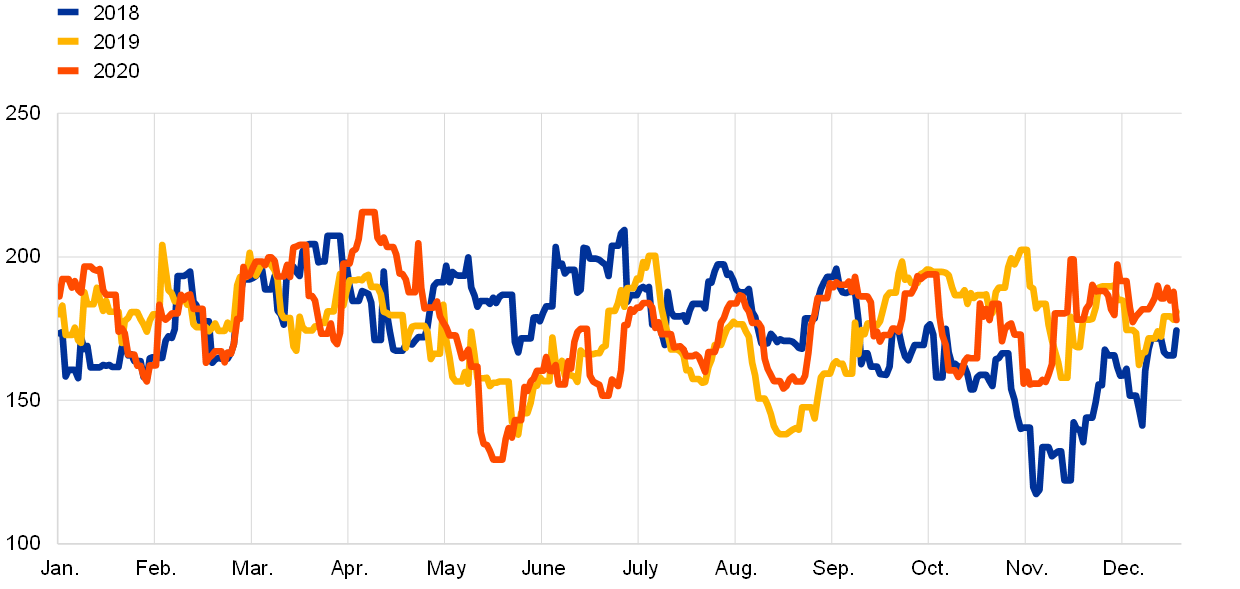

Trends in daily transaction volumes

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Note: The period under review is indicated by a light blue background.

The relationship between reporting dates and volumes

Turnover in the secured segment tends to drop at quarter-end and year-end, for the purposes of “window dressing” (see Chart 1.2 above). Close to regulatory reporting dates banks reduce the size of their balance sheets in order to comply with prudential regulations and to optimise bank levies. During these periods a general reduction of borrowing activity is therefore observed when banks’ leverage ratio is close to the regulatory minimum and/or they prefer to engage in collateral swap trades (e.g. bond vs. bond removing the two cash legs) to increase netting.

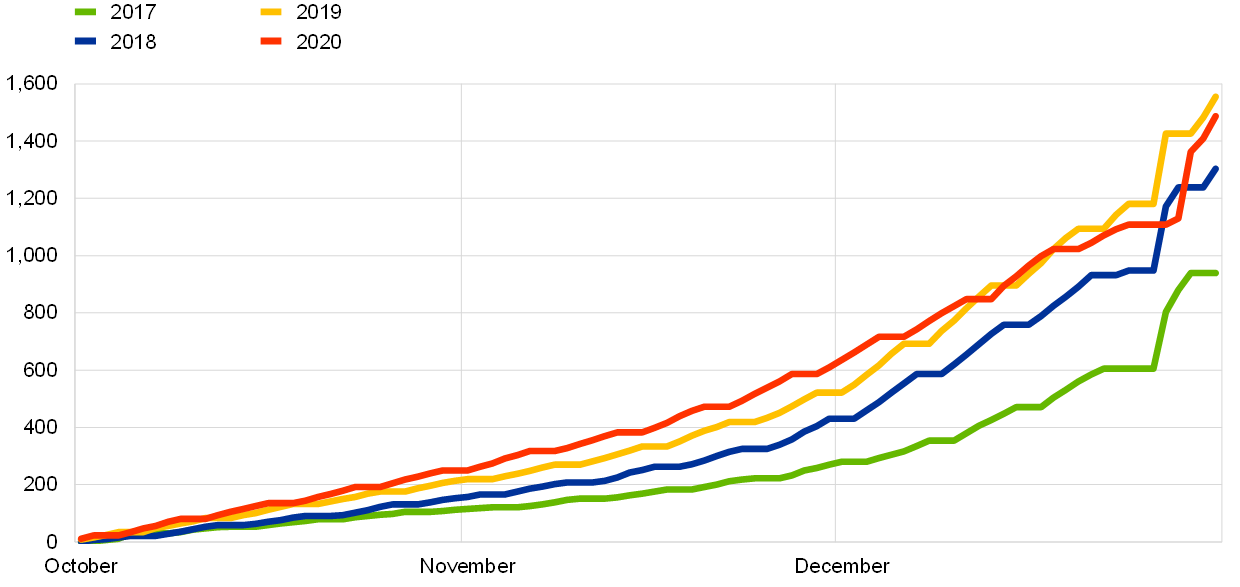

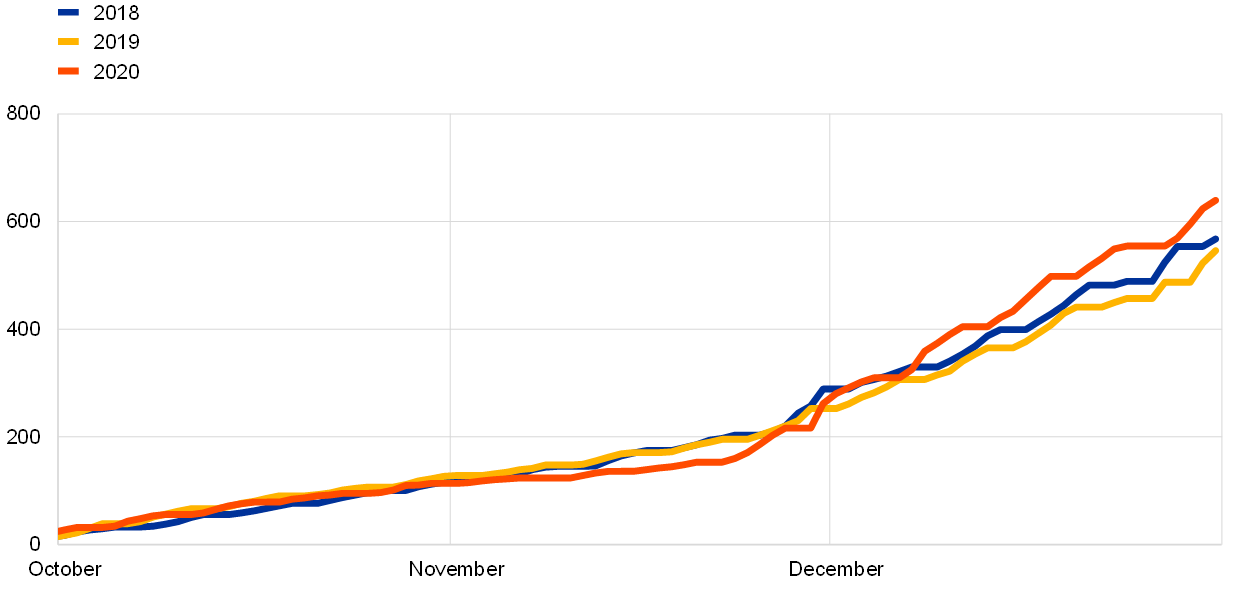

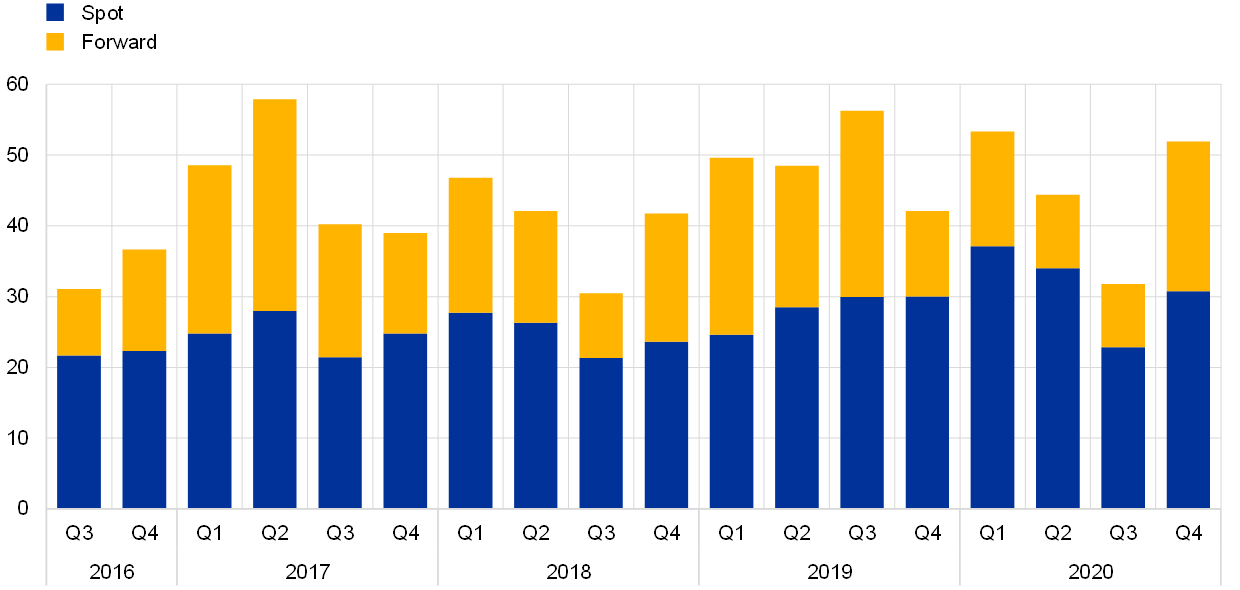

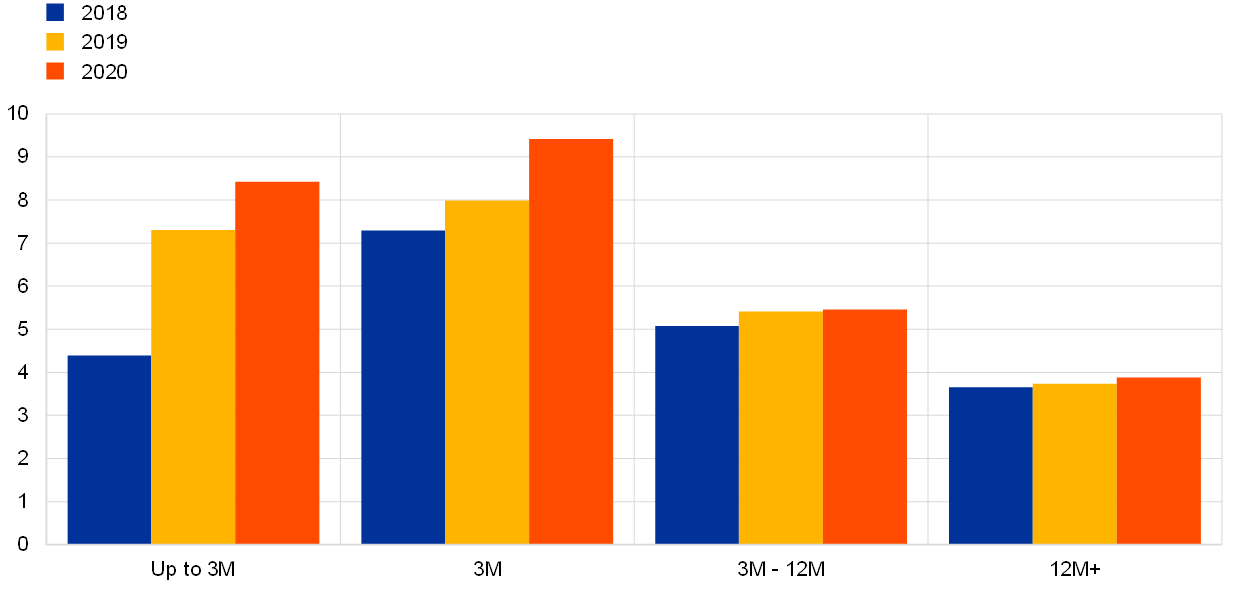

Significant prefunding activity is noticeable around year-end dates since 2018 (see Chart 1.4). Prefunding consists of conducting trades that span the year-end reporting date but are agreed well ahead of the settlement date. Spreading out the impact of year-end trading over a longer period allows clients and dealers to minimise the tensions which arise when last-minute demands can only be accepted by dealers at punitive rates. Since 2017 the volume of prefunding has increased significantly and has been cited by market participants as one of the reasons behind the less stressed year-ends seen in recent years.

Chart 1.4

Year-end prefunding in the repo market

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Includes secured trade volumes that settle up to three months before year-end and mature up to three months after year-end. Only collateral by Belgian, German, Spanish, French, Italian and Dutch counterparties is taken into account. Only TARGET2 business days are used. Cumulative volumes.

1.2 Collateral

General collateral and specific collateral size

There are two collateral management subsegments for secured trading: general collateral (GC) and specific collateral (SC). GC trades are undertaken during a search for cash funding against a pre-defined pool of substitutable collateral (collateral baskets) – sometimes they are classified as tri-party GC trades as collateral management is often outsourced to a third party. In SC trades the counterparties manage the collateral themselves. SC trades can be divided into two categories depending on their rate: (i) trades which take place at rates at or close to the GC rate; and (ii) trades for a specific bond which take place at rates noticeably below the GC rate, and which are often called “special” repo transactions to emphasise the importance of the security on the transaction value.

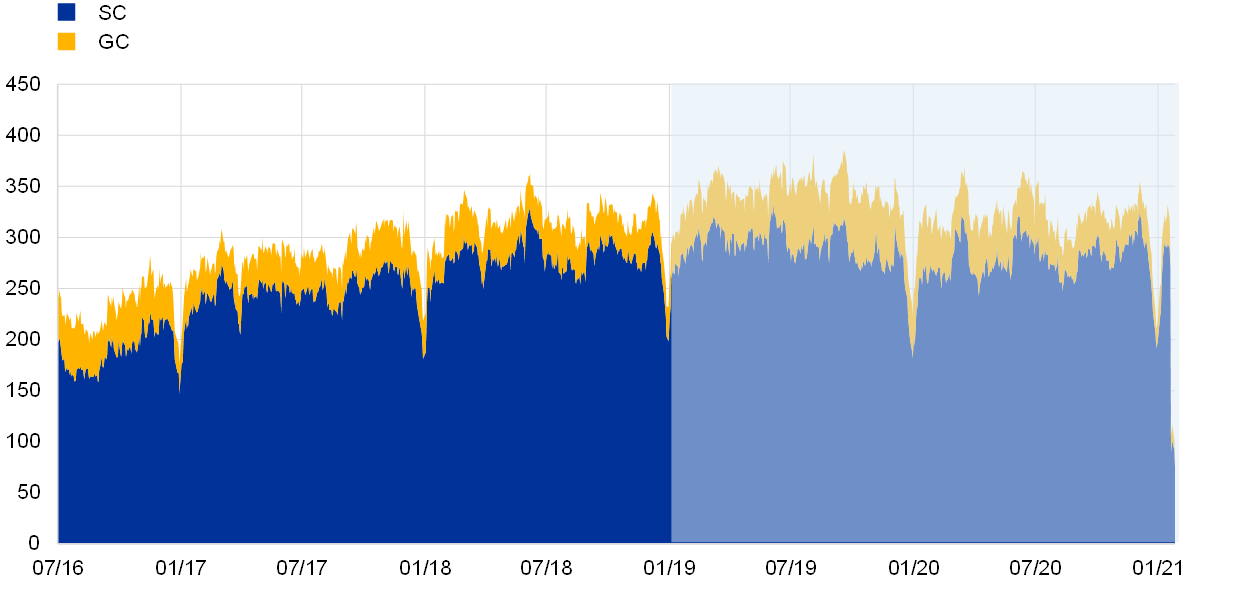

GC trades represent only 10% of total secured transactions while the remaining 90% are specific collateral (see Chart 1.5). The small share of GC trades increased in the second half of 2019, coinciding with the introduction of the two-tier system. This increase was particularly concentrated in GC trades using Italian collateral. Overall, specific trading has remained dominant in recent years, reflecting firms’ desire to exercise greater control over collateral management practices.

Chart 1.5

Secured volumes by collateral type

(EUR billions)

Sources: BrokerTec and MTS.

Notes: O/N, S/N and T/N maturities only. Euro area countries: BE, DE, IE, GR, ES, FR, IT, NL, AT, PT, SI, FI.

2019‑20 trends

Government bonds are the dominant type of collateral in the euro-denominated repo market, accounting for 85% of all transactions. This share remained stable during the review period and is in line with previous money market study results. The reliance on sovereign collateral can be explained by the zero-risk weight on sovereign bond holdings and high levels of liquidity of government bonds compared with other securities. The bonds are also easy to source for participants given the large size of the euro government bond market.

The most-used government bonds are issued in the biggest euro area economies. Given the size, breadth and depth of the respective sovereign debt markets, bonds issued by governments in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and Belgium account for 92% of the total public collateral used in secured transactions. The share of these six sovereign issuers used to secure repo transactions has been very stable over the last couple of years.

A smaller share of transactions (15%) used private sector collateral. Bonds issued by financial companies accounted for most of the private sector collateral. At the beginning of 2020, the use of private sector collateral increased, reaching a peak of around 19% in May 2020 at the expense of general government collateral. This was attributed to the elevated levels of private debt issuance during that period, as market conditions improved. The actions of the Eurosystem, which included an increase in private bond purchases and measures to temporarily ease collateral framework, also contributed to the improvement of market conditions and supported this dynamic.

Maturity analysis shows that non-government collateral is more prevalent in repo transactions at longer maturities. Debt issued by financial corporations is used in 40% of trades which are longer than one month even though they only represent 12% of total repo transactions.

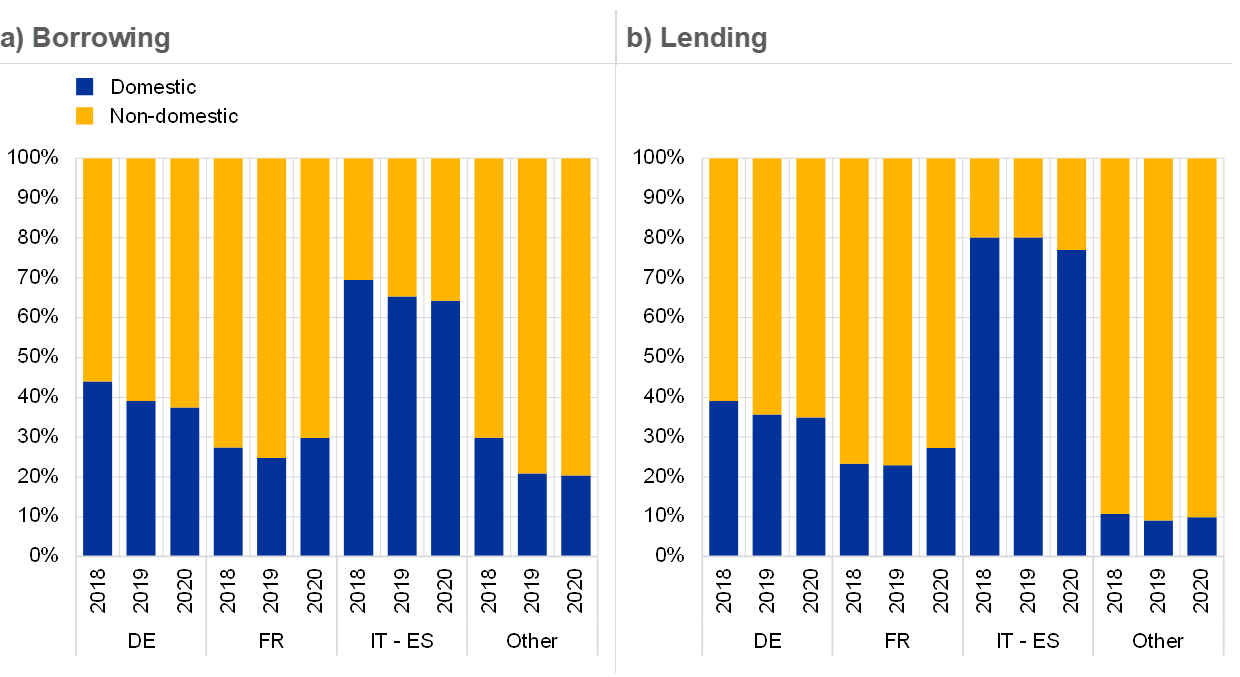

Euro area banks used predominantly non-domestic collateral in their secured transactions, except for those in Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain (see Chart 1.6). The share of non-domestic collateral (collateral issued in a country other than that in which the bank is domiciled) is around 63% of the total weighted volume. Nevertheless, the share of domestic collateral usage differs between participants. Italian and Spanish banks report a higher use of domestic collateral, while German and French banks report a higher share of non-domestic collateral.

Chart 1.6

Origin of government collateral used, by location of reporting agent

(percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Note: Only transactions secured by government collateral.

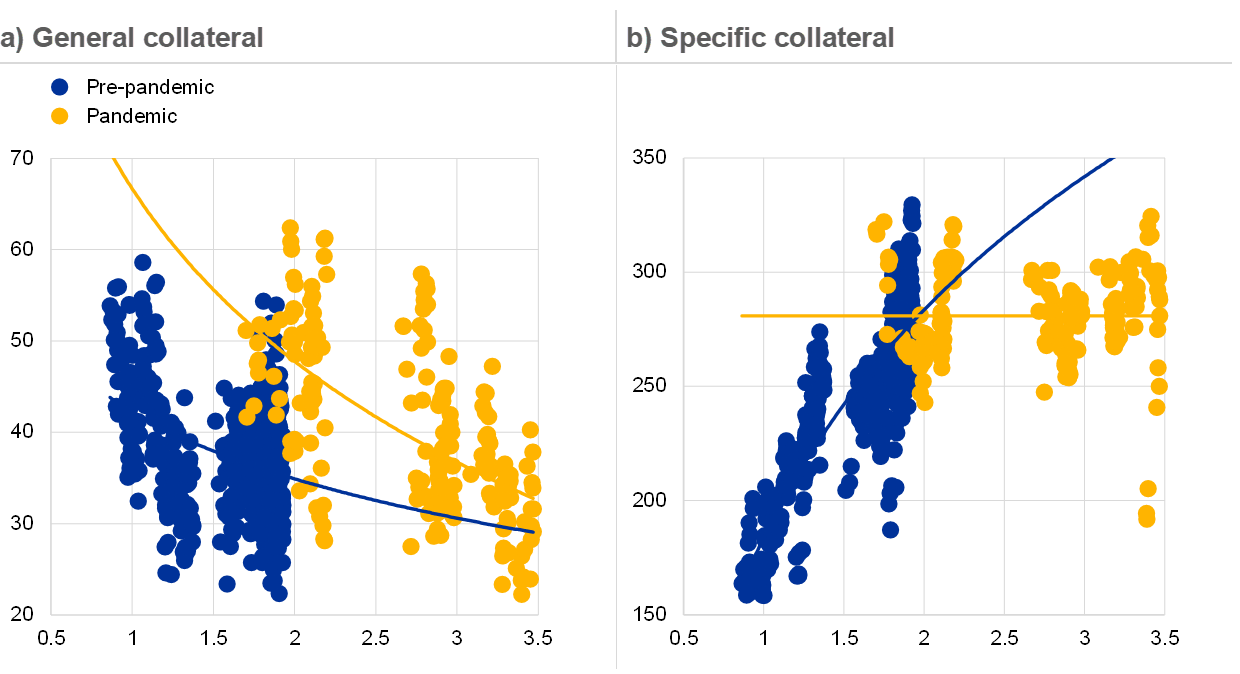

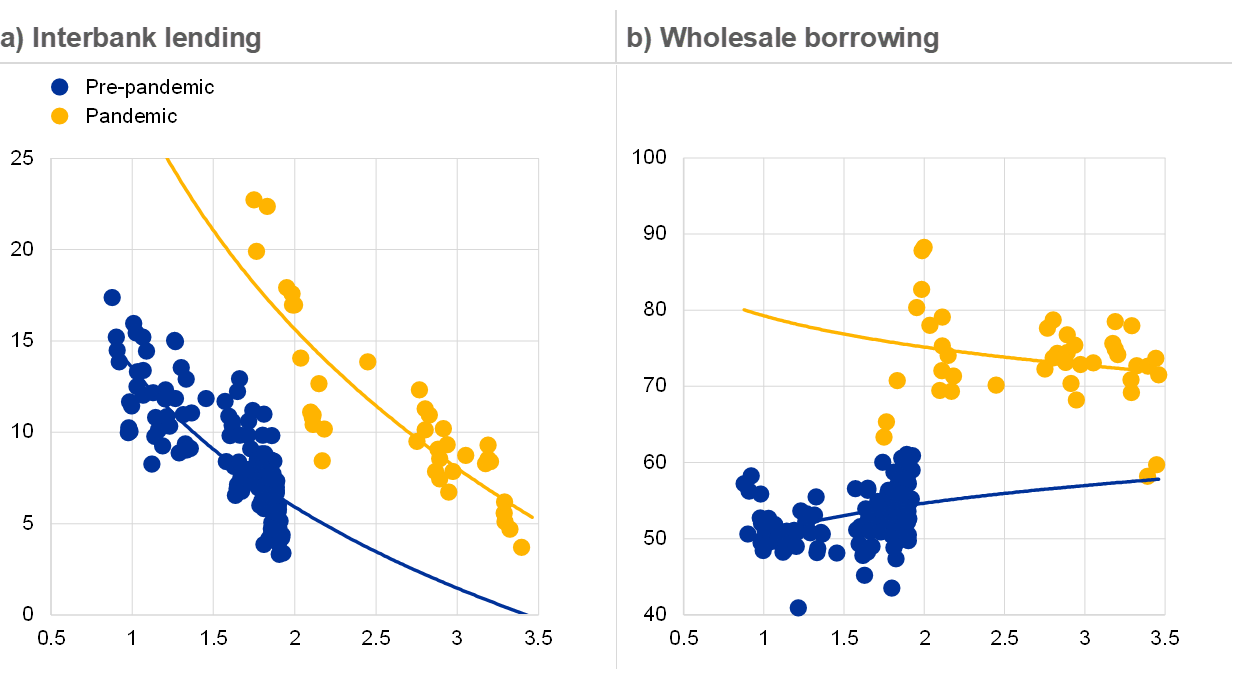

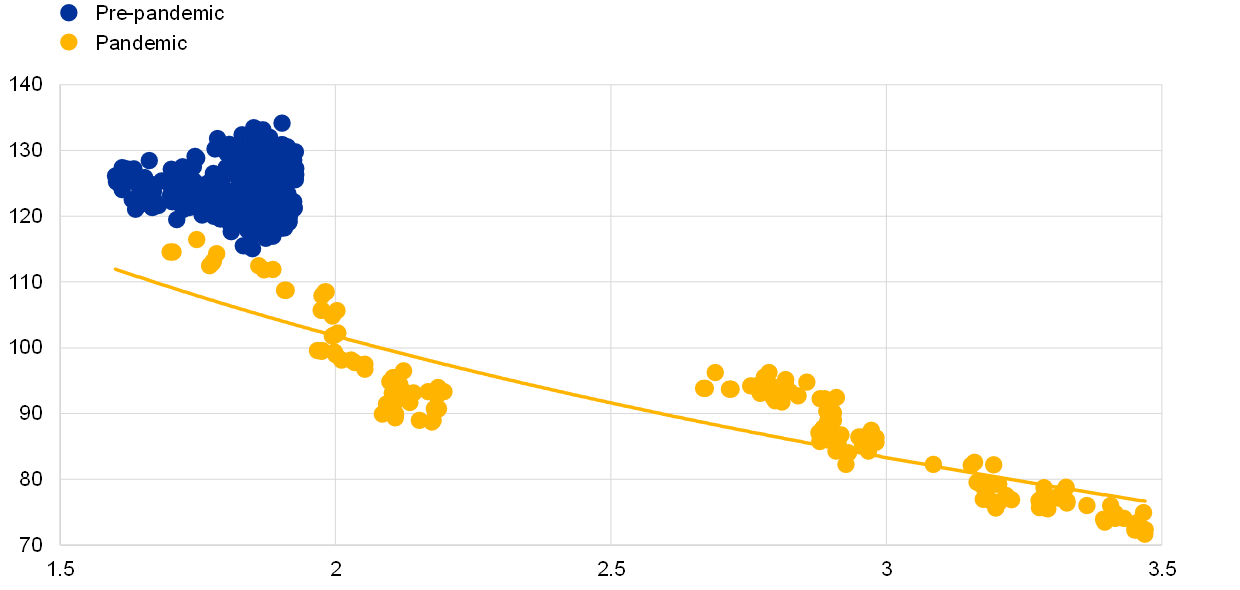

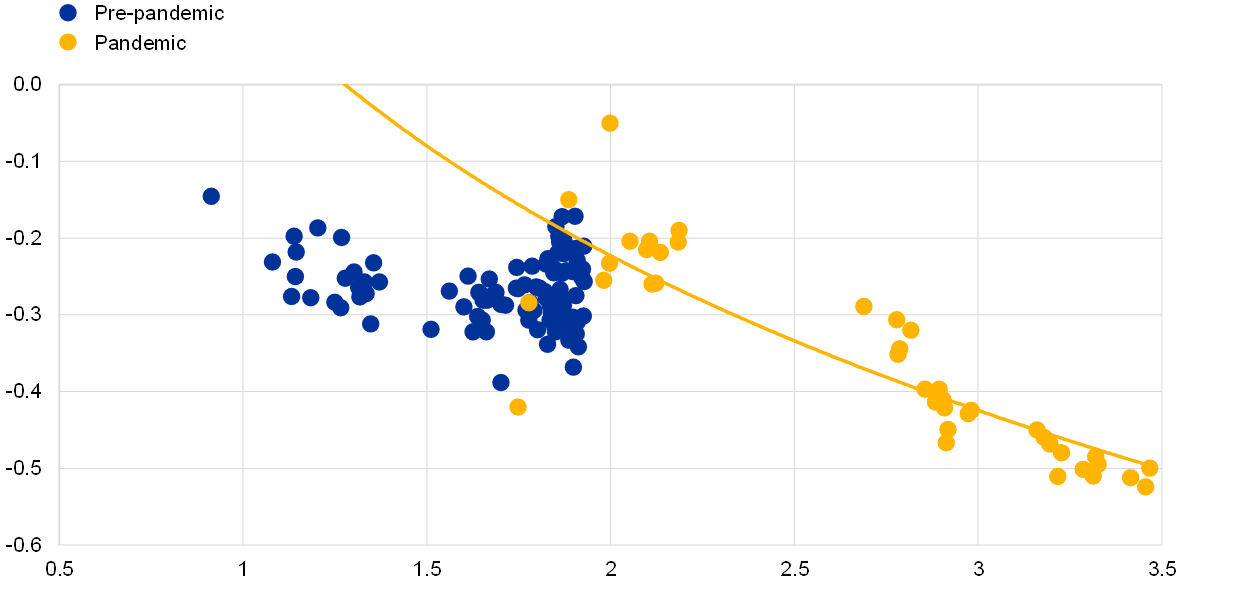

The relationship between excess liquidity and GC/SC volume

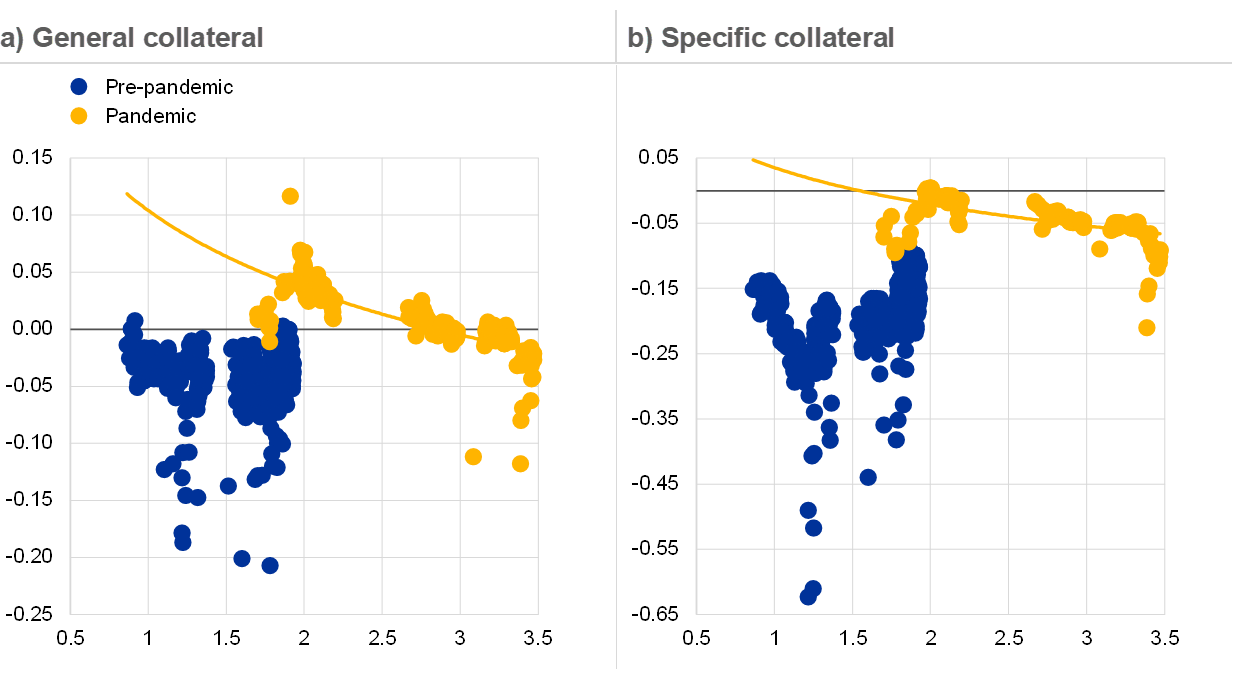

GC and SC repo transactions display different correlations with excess liquidity, given their differing scope (see Chart 1.7). Prior to the pandemic, an increase in excess liquidity was associated with a notable increase in SC repo volumes and a decline in repos backed by GC. This difference is because the Eurosystem intervention alters the supply of both cash and collateral. GC transactions – exclusively used for cash management purposes – decline, on average, as the Eurosystem’s liquidity injection reduces the banking sector’s funding needs. However, SC transactions – often used for collateral management purposes – tend to increase. This can be explained by the reduction in collateral available in the market due to the sizeable amount of securities drained by the Eurosystem via both asset purchases and collateralised lending operations. During the COVID‑19 crisis, the positive correlation between SC repo volumes and the growth of excess liquidity has ceased to apply. This appears to indicate that the Eurosystem’s securities lending programme has managed to alleviate the collateral shortage, reducing market needs for SC. Moreover, national governments increased their bond issuances, making more securities available for trades also in the secondary market. On the other hand, the negative correlation between the growth of excess liquidity and GC repo volumes is still observed and has even strengthened.

Chart 1.7

Correlation between secured transaction volumes and excess liquidity

(y-axis: EUR billions; x-axis: EUR trillions)

Sources: BrokerTec/MTS and Bloomberg (liquidity statistics).

Notes: The blue dots represent the period before the COVID‑19 pandemic when excess liquidity was increasing (July 2016 – December 2018). The yellow dots represent the expansion of excess liquidity following the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic (March – December 2020). The horizontal axis refers to daily euro excess liquidity. The vertical axis refers to daily total secured O/N, S/N and T/N volumes of euro area countries. Only government collateral.

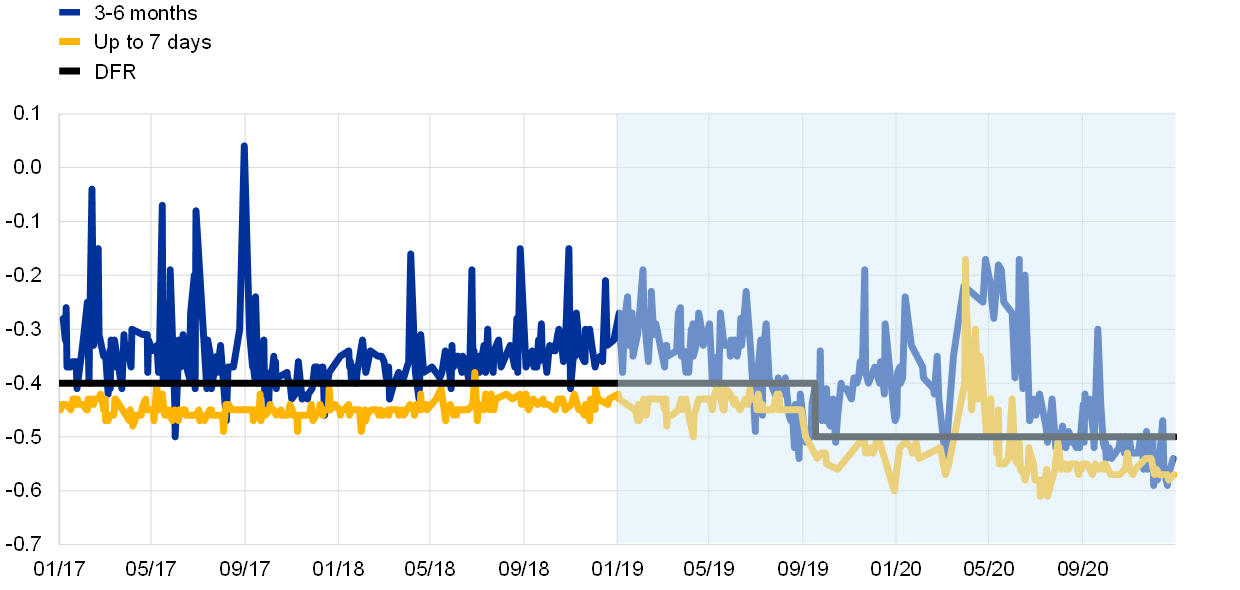

1.3 Rates

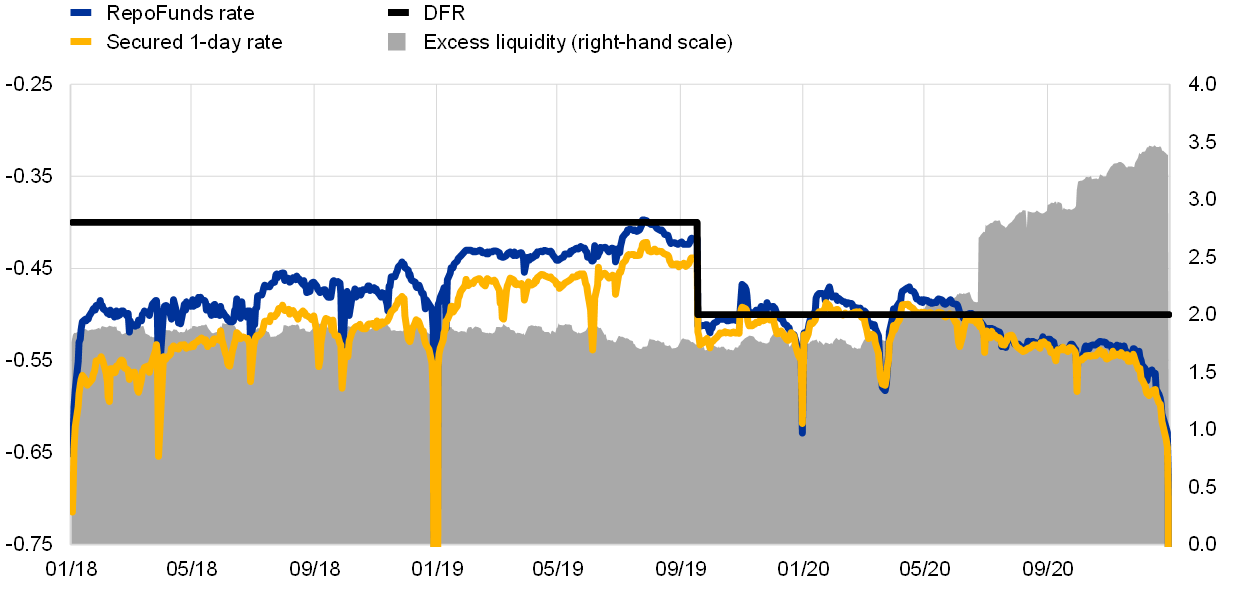

2019‑20 trends

The euro repo rate traded below but closer to the DFR until mid‑2020, when secured rates began to fall back below the DFR as a result of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy actions (see Chart 1.R.1). Repo rates reflect developments in the supply of and demand for both cash and collateral. In 2019, net asset purchases by the Eurosystem under the asset purchase programme (APP) ceased, and only reinvestments were made. However, during this phase the Eurosystem continued its securities lending activities. These two factors increased the availability of government bonds in the market, so repo rates rose towards the DFR. As regards the cash, despite the stable excess liquidity, the introduction of the two-tier system in October 2019 provided an incentive to redistribute liquidity among euro area bank. Most of the cross-border redistribution within euro area took place through the secured segment. As a result of these transactions, repo rates against non-core collateral temporary increased, reflecting the higher rates paid by some Italian banks to borrow liquidity to fulfil their exempt tier. This increase was only temporary because banks receiving market liquidity achieved more favourable conditions in the TLTRO III monetary policy operations offered latter by the Eurosystem.

In 2020 collateral availability declined, while the amount of liquidity in the Eurosystem increased, putting further downward pressure on repo rates (see Chart 1.8). Eurosystem asset purchases increased sharply in 2020 in response to the COVID‑19 crisis. During the pandemic the Eurosystem has eased monetary policy and liquidity provision has remained ample. The third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO‑III) saw very large take-up, adding further liquidity to the euro area banks. As a result, the demand for cash in the repo market decreased. At the same time, the demand for collateral has remained sufficiently firm to meet regulatory requirements, albeit in the face of a decrease in the availability of collateral. While euro area governments undertook large net issuances of securities in 2020, the Eurosystem asset purchases increased sharply in 2020 reducing the supply of collateral available to the repo market in exchange for reserves. Both of these factors contributed to the downward pressure on repo rates during 2020 and, as a result of these developments, repo rates have begun to fall further below the DFR.

Chart 1.8

Repo rates, the deposit facility and excess liquidity

(left-hand side: percentages; right-hand side: EUR trillions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR, liquidity statistics published in wire services), Bloomberg (RepoFunds rate).

Note: Secured 1‑day rate is calculated as a volume-weighted average rate of secured MMSR trades with maturity of 1‑day (O/N, S/N, T/N) collateralised with government securities issued by euro area countries. The vertical axis has been cut off at ‑0.8% in the interests of readability. Cut-off points: year-end 2018 secured 1‑day rate ‑1.59% and RepoFunds rate ‑1.22%; year-end 2020 secured 1‑day rate ‑1.60% and RepoFunds rate ‑1.87%. RepoFunds Euro is a repo benchmark against government collateral produced by the CME Group.

The spread between the repo rates of different jurisdictions narrowed significantly (see Chart 1.9). Its convergence coincided with the large increase in excess liquidity injected by the APPs and TLTRO‑III. The secured market has also functioned well during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Most secured rates remained stable, although volatility between core and non-core increased slightly, reflecting a flight-to-quality and an increased demand for secured trading. From the end of February 2020, core repo rates decreased to a level close to ‑65 basis points, while Italian repo rates remained broadly unchanged or even slightly increased. The decrease in repo rates implied that investors preferred perceived safer assets. At the same time, demand for cash also increased, as market participants looked to increase cash holdings to offset cash outflows (non-banks) or to meet borrowing demand (banks). After the ample injection of liquidity by the Eurosystem and other central banks, repo rates had begun to normalise by mid-April.

Chart 1.9

Government repo rates by jurisdiction

(percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: Volume-weighted average rate per collateral jurisdiction – only government collateral is included. Plotted against settlement date. The scale is limited to ‑1%, the year-end developments in 2018 and 2020 values are cut off in the interests of readability. Only trades with O/N, S/N and T/N maturities. The rate includes both borrowing and lending transactions.

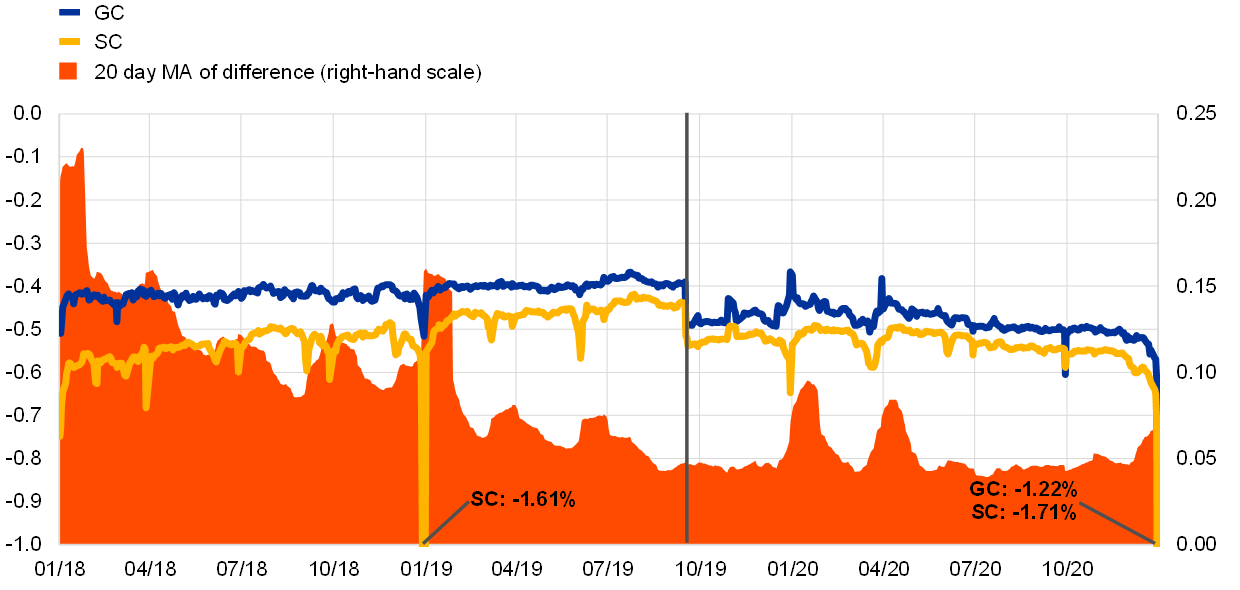

The spread between GC and SC rates progressively decreased over the review period (see Chart 1.10). The GC/SC spread measures the difference between the rates on transactions backed by securities from a basket of collateral (GC repo rates) and the rates on transactions backed by specific collateral (SC repo rates). An increase in the spread signals increased demand for SC. The market for SC is sometimes driven by the particular specialness of the collateral, i.e. bonds that are traded at much lower rates because they are in high demand and/or because they are the cheapest-to-deliver bond in the futures market. For such reasons, the demand for these “special” securities can increase on the delivery dates of futures contracts and on reporting dates. In addition, regulatory constraints encourage financial intermediaries to hold high quality collateral on their balance sheets or prevent them from lending out bonds on the repo market, exacerbating the dynamic. Several factors have led to a compression of the GC/SC spread compared with the previous review period. First, the Eurosystem ceased net asset purchases in December 2018, lowering the absorption of collateral from the market and hence contributing to increased collateral availability. Second, market participants adopted more pronounced pre-funding strategies and limited their demand for specific securities around reporting dates. Finally, banks that were not constrained by regulatory factors were more willing to lend bonds in the repo market.

Chart 1.10

Repo rates for general collateral and specific collateral trades

(left-hand side and right-hand side: percentages)

Source. BrokerTec, MTS, ECB calculations.

Notes: Includes O/N, S/N and T/N maturities. Rates are a weighted average of trades against German, Spanish, French and Italian government collateral. The vertical grey line represents the DFR cut from ‑40 to ‑50 basis points in September 2019. The y-axis has been cut off at –0.75% in the interests of readability. The spread is smoothed by the 20‑day moving average.

The introduction of the two-tier system led to temporary upward pressures on non-core repo rates as banks with unused allowances borrowed cash in the secured market. The introduction of the two-tier system led to an increase in interbank activity, which predominantly took place in the secured market. The upward pressure was short lived but was most pronounced in collateral rates for non-core jurisdictions, where banks typically had low holdings of excess reserves, resulting in unused allowances under the two-tier system. The scheme incentivises the trading of reserves between banks which have unused allowances and can borrow cash at rates up to the MRO rate and banks with high holdings of excess liquidity which should lend reserves at rates above the DFR. The repo market represented the primary source of funding for banks with unused allowances. The limited upward pressure on repo market rates implied that the two-tier system multiplier was calibrated carefully, ensuring it was not too high and did not have a significant tightening effect on secured market rates.

The relationship between excess liquidity and GC/SC rates

Large liquidity injections during the COVID‑19 pandemic have slightly reduced both SC and GC repo rates, while maintaining a low spread between them (see Chart 1.11). The increase in excess reserves during the pandemic has coincided with both GC and SC repo rates decrease further below the DFR. This negative correlation seems to confirm the description of the trend above, where GC repo rates decreased on the back of the Eurosystem’s accommodative policy, mainly following theTLTRO‑III.4 allotment and SC repo rates decreased on the back of an increasing scarcity of government bonds in the market following the APP and PEPP. In the period July 2016 and December 2018 the direction of the relationship between excess liquidity and repo rates had been less clear[4].

Chart 1.11

Correlation between the secured rates spread versus the DFR and excess liquidity

(y-axis: percentages; x-axis: EUR trillions)

Sources: BrokerTec/MTS and ECB (liquidity statistics published in wire services).

Notes: The blue dots represent period before the COVID‑19 pandemic when excess liquidity was increasing (July 2016 – December 2018). The yellow dots represent the expansion of excess liquidity following the outbreak of COVID‑19 pandemic (March – December 2020). The vertical axis depicts daily volume-weighted average secured O/N, S/N and T/N rates spread versus the DFR. Horizontal axis reflects the daily excess liquidity in the euro area. Only government collateral.

The relationship between reporting dates and rates

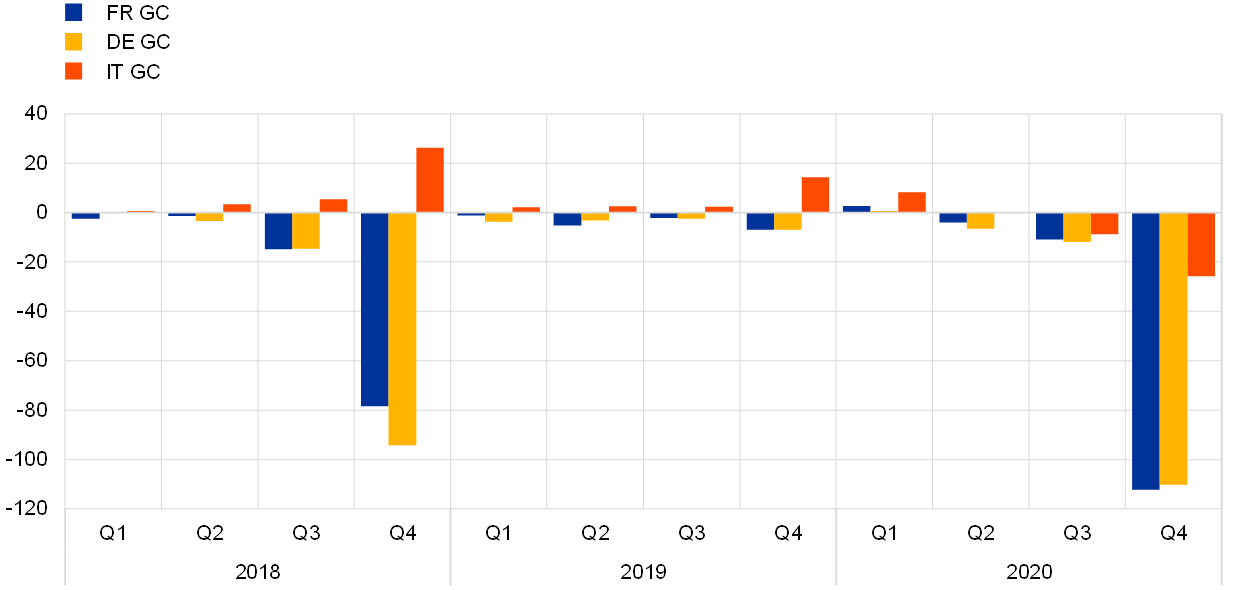

Secured rates exhibit considerable seasonality, with rates moving sharply at period-end dates (see Chart 1.12). These moves may be attributed to the banks’ policy of avoiding trades that settle on reporting dates and therefore influence their balance sheet and collateral positions. Year-end pressures are particularly acute and coincide with a relatively less liquid time for the market. In order to disincentivise activity, market-makers set punitive rates for repo trades on period end dates. The direction of the move is driven by the desire to hold assets of the highest credit quality. The repo rates of collateral of higher-rated issuers generally fall as this high-quality collateral is in demand, while the repo rates for government bonds of issuers with relatively low ratings – even though they also account for 0% of risk-weighted assets – tend to rise (this latter pattern reversed in the third and fourth quarter of 2020). The 2019 year-end effect on rates was relatively contained for core countries, as the imbalance of cash and collateral was less pronounced than on previous occasions. The decline of repo rates over the 2020 year-end was strong, although in line with market expectations, due to the reduced availability of government bonds in the market in light of the net asset purchases under PEPP and increasing excess liquidity. In 2020 the repo rates of all the jurisdictions decreased due to the low-risk environment, high level of excess liquidity and the greater willingness of foreign investors to demand non-core collateral.

Chart 1.12

GC repo rate day-to-day moves at quarter-ends

(basis points)

Sources: BrokerTec, ECB calculations.

Note: Countries included are France (FR), Germany (DE) and Italy (IT).

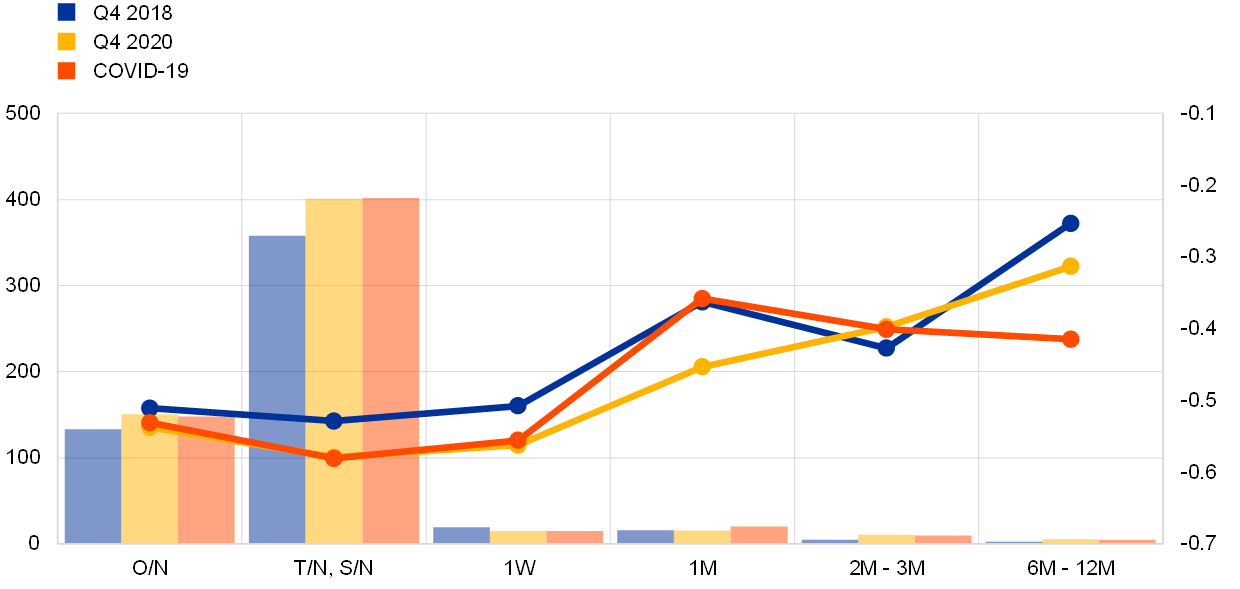

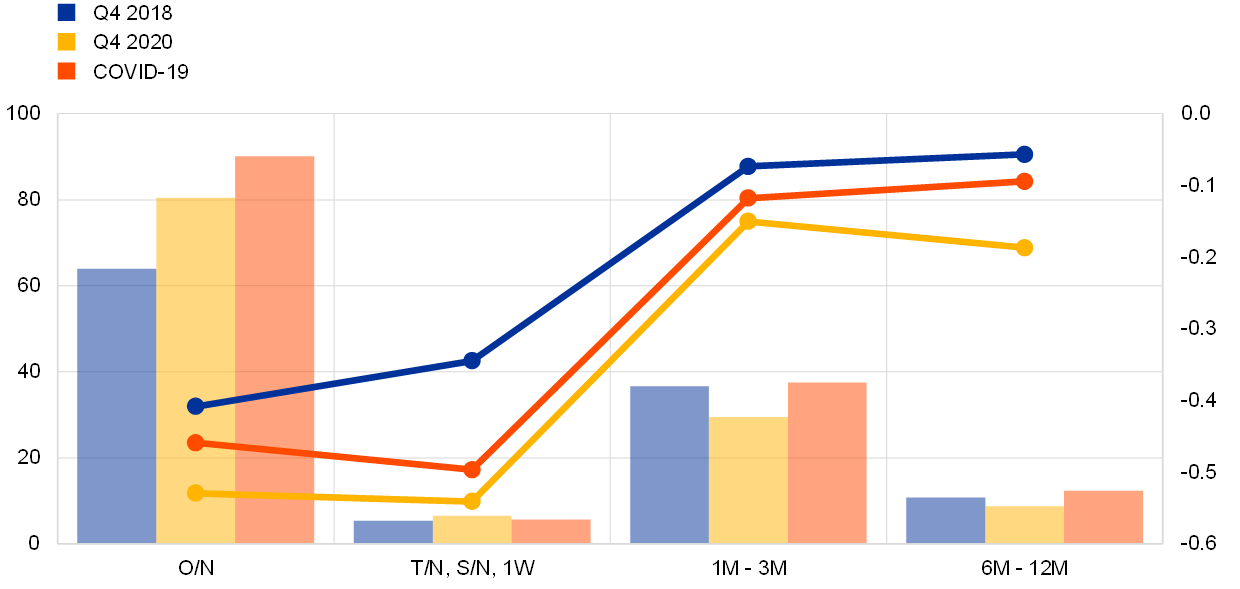

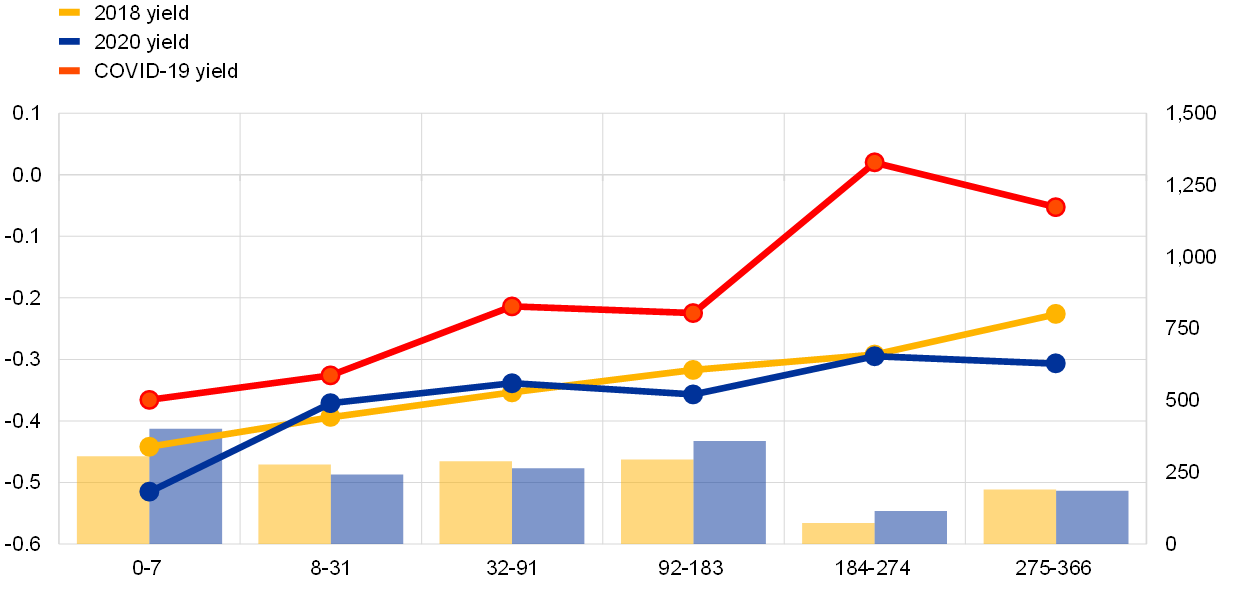

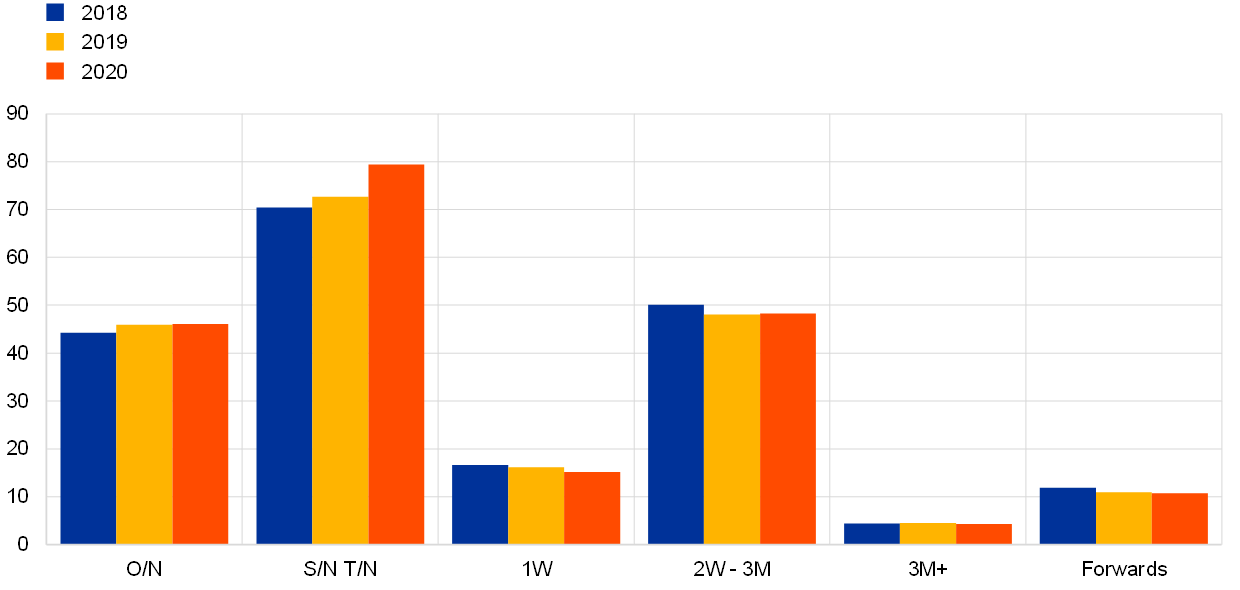

Yield curve

Compared with two years ago, the yield curve has shifted downwards, while maintaining a mild upward slope (see Chart 1.13). For most maturity buckets, secured rates declined over the period under review, given the very accommodative monetary policy stance which eased funding conditions. The term structure of the weighted average repo rates is flat from overnight to one week and has a mild upward slope for longer tenors. Banks borrow cash at slightly lower rates than they lend it, as reflected in the bid-ask spreads. This spread increases as the maturity of the trade increases. At the peak of the COVID‑19 crisis secured rates remained contained, in contrast to rates in the unsecured segment.

Chart 1.13

Yield curve

(left-hand side: EUR billions; right-hand side: percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: COVID‑19 represents the period 17‑23 March 2020, reflecting the same period when the unsecured market experienced tension. The left-hand side axis and the bars represent the average daily volume per maturity. The right-hand side axis and the lines represent the volume-weighted average rate per maturity.

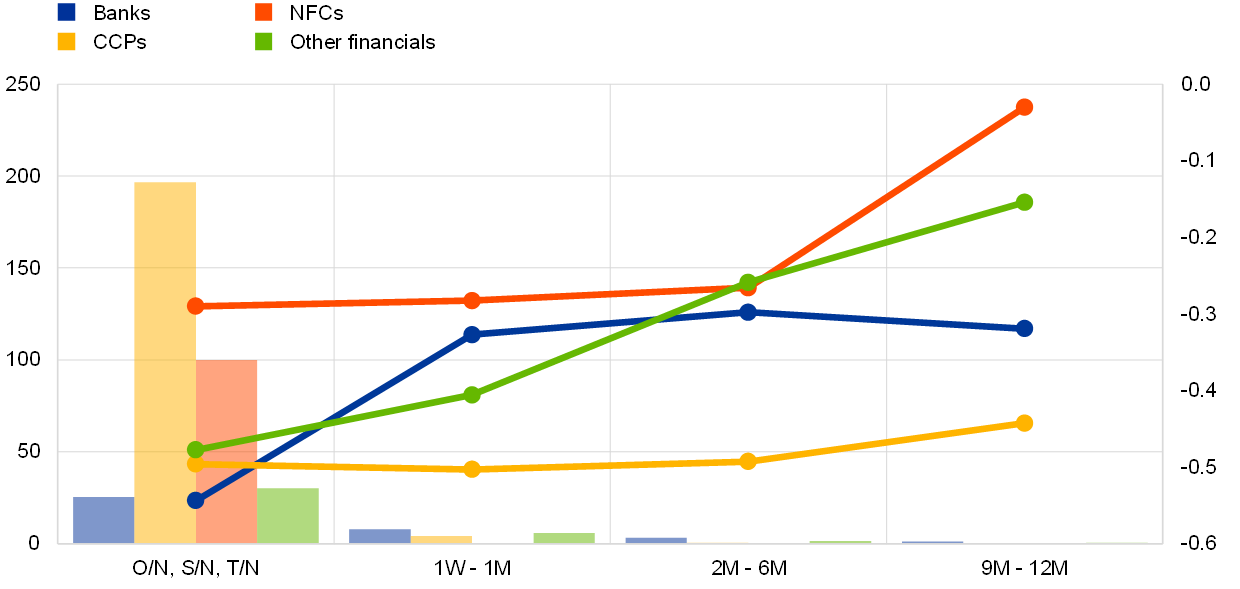

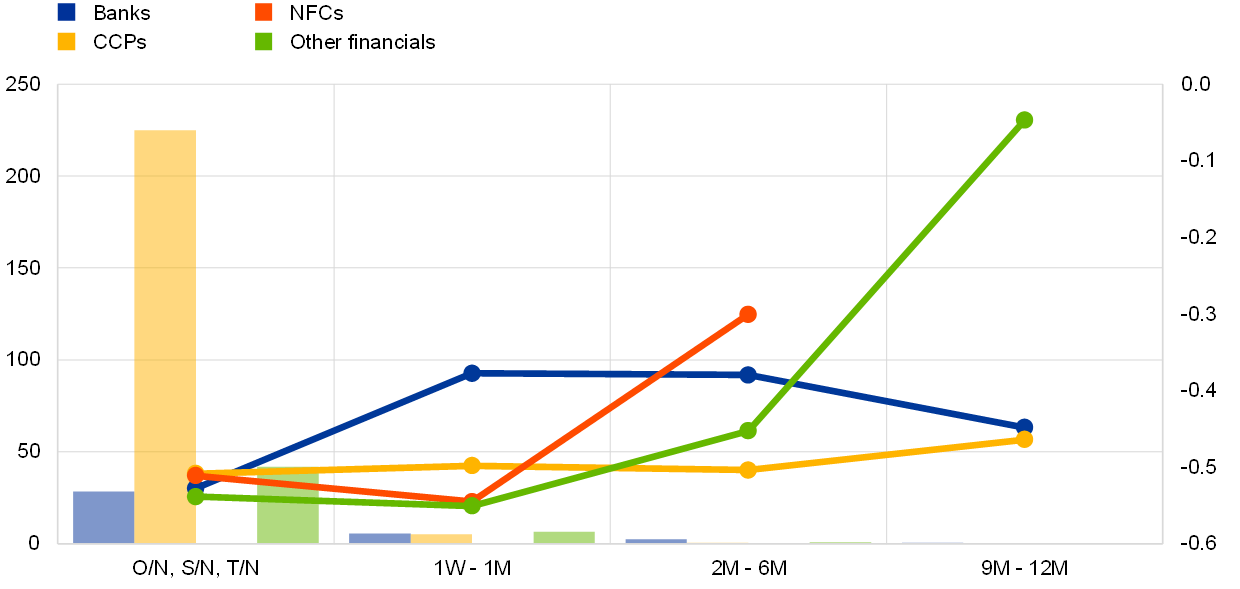

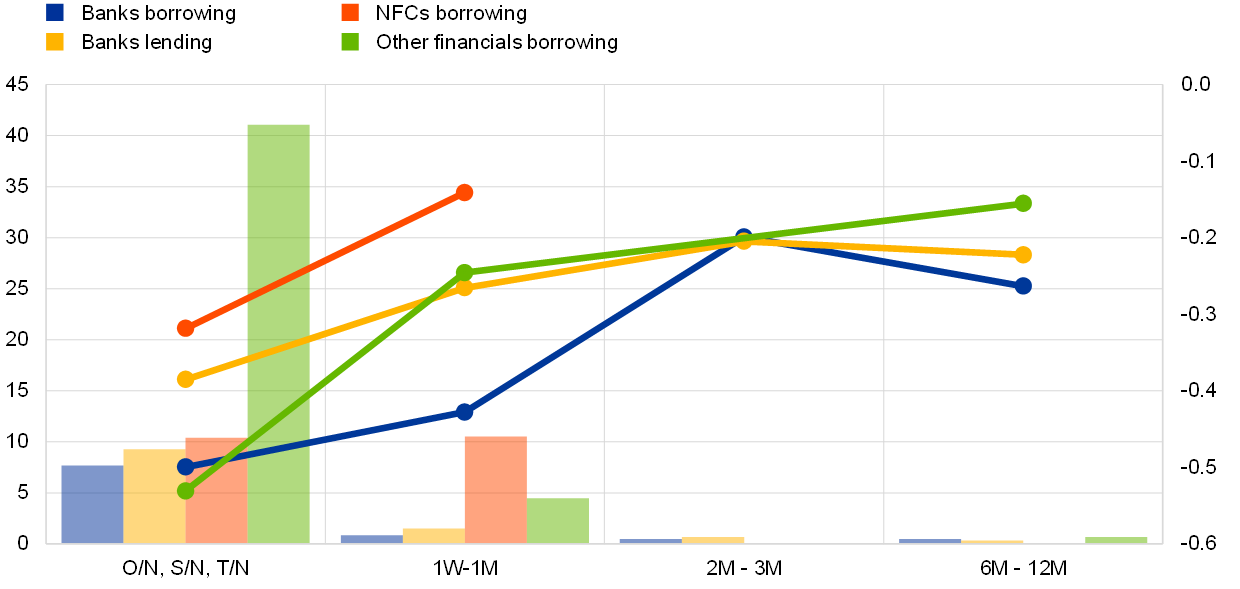

The yield curve exhibits segmentation based on trading counterparty type (see Chart 1.14). Rates for lending transactions with NFCs[5] were above those for banks and other financials for most maturities, although the slope of the yield curve is relatively flat. Interbank and other financial sectors show a similar pattern, but with short maturities at rates close to the DFR and an upwardly sloping yield curve. The benefit of using CCP clearing is also visible in a yield curve which is below that of bilateral equivalents. Trades cleared with CCPs have minimised counterparty risk, leading to a flat yield curve structure.

Chart 1.14

Yield curve per counterparty type

(left-hand side: EUR billions; right-hand side: percentages)

a) Lending

b) Borrowing

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Note: The left-hand side axis and the bars represent the average daily volume per maturity for each counterparty type. The right-hand side axis and the lines represent the volume-weighted average rate per maturity. Panel (a) plots the yield curve for lending transactions and panel (b) for borrowing transactions. The sample covers transactions from 2019 to 2020. Other financials include all financial corporations apart from banks and central banks. Confidential values are hidden.

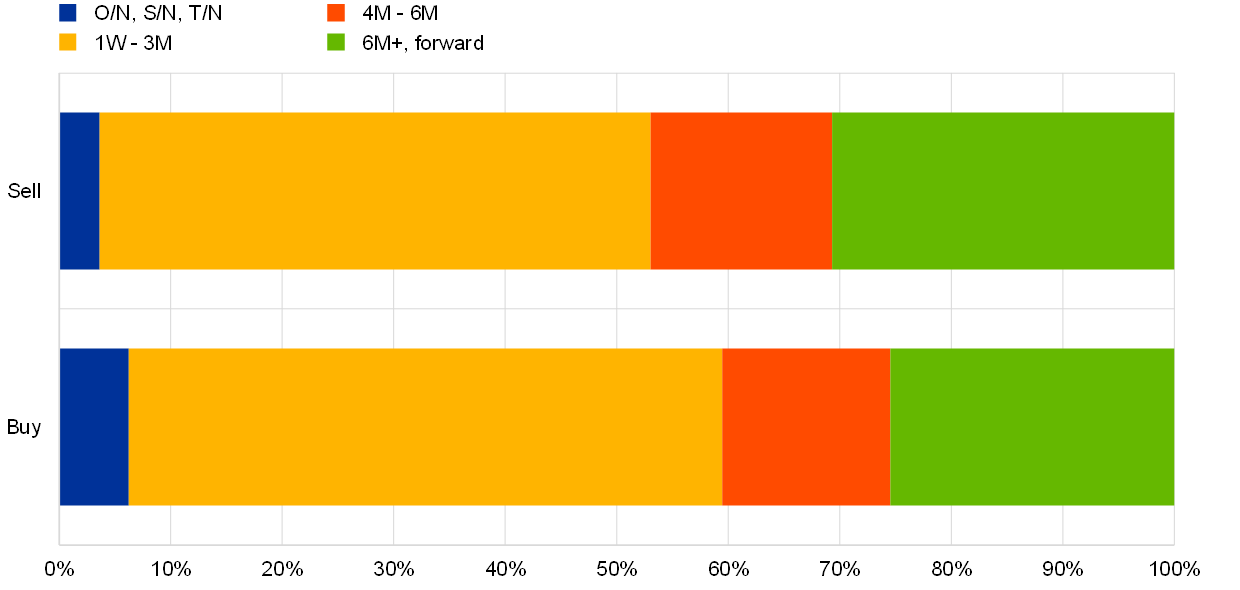

1.4 Maturities

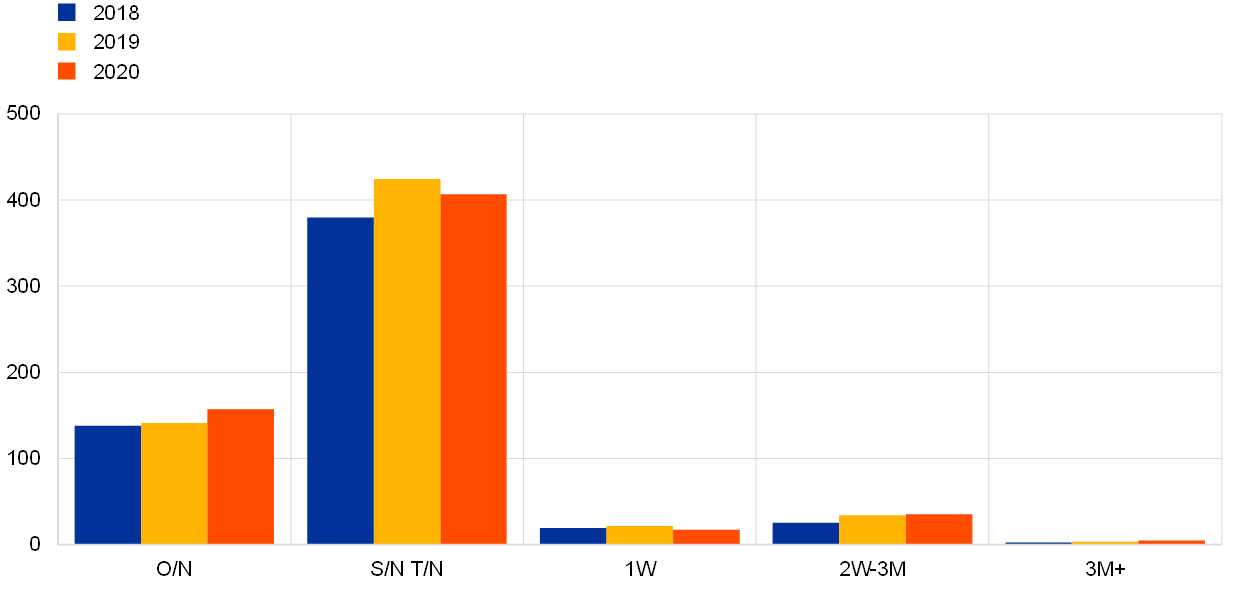

Transaction volume per maturity

Most secured transactions are concentrated in the one-day maturity bucket (see Chart 1.15)[6]. The cumulative share of maturities up to one-month of overall secured lending and borrowing remains very high (95% in 2020). Among transactions with a one-day maturity there was a small decline in spot/next lending and borrowing – this was offset by a growing share of overnight transactions. Maturities of one month or longer are used more widely in lending than in borrowing activities.

Chart 1.15

Volumes by maturity bucket over time

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Note: O/N – overnight; S/N – spot/next, T/N – tomorrow/next. Confidential values are hidden.

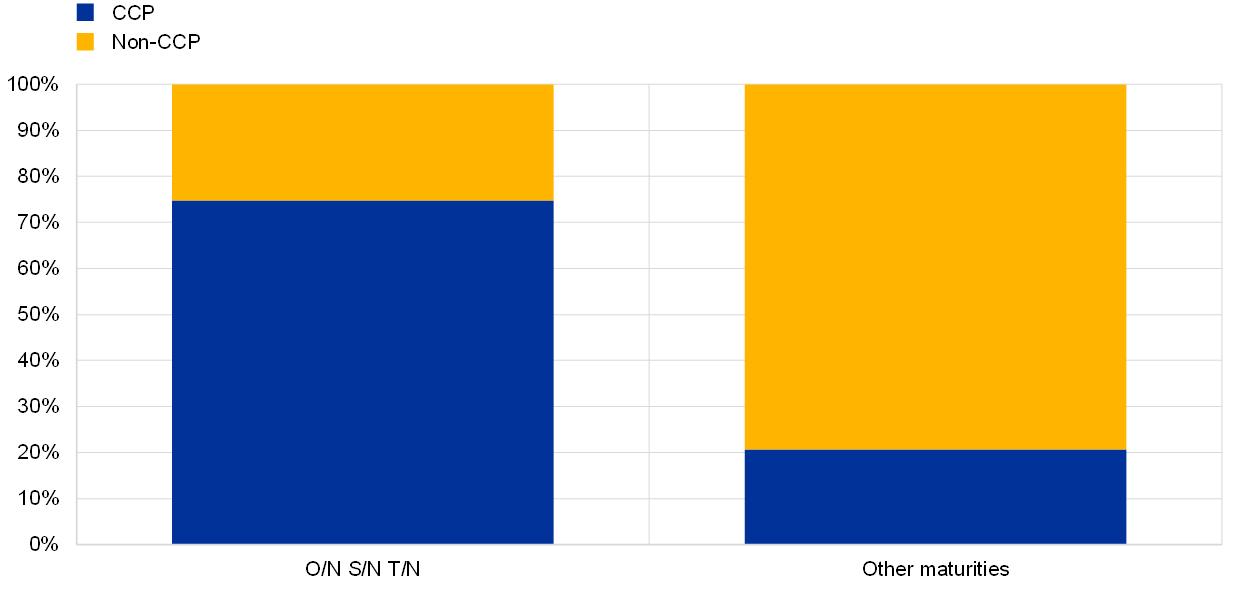

Trades with a shorter maturity profile tend to be concentrated in CCPs, while those with longer tenors are traded bilaterally (see Chart 1.16). CCPs account for around 75% of one-day maturity trades, but for only around 20% of trades with longer tenors. Market intelligence suggests that trading higher volumes at shorter maturities incentivises banks to net off their positions with CCPs in order to gain efficiency in their use of collateral.

Chart 1.16

Share of centrally cleared secured trades by maturity

(percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: Share of total secured transaction volume over the 2018‑20 review period – split by counterparty type and maturity.

O/N – overnight; S/N – spot/next; T/N – tomorrow/next.

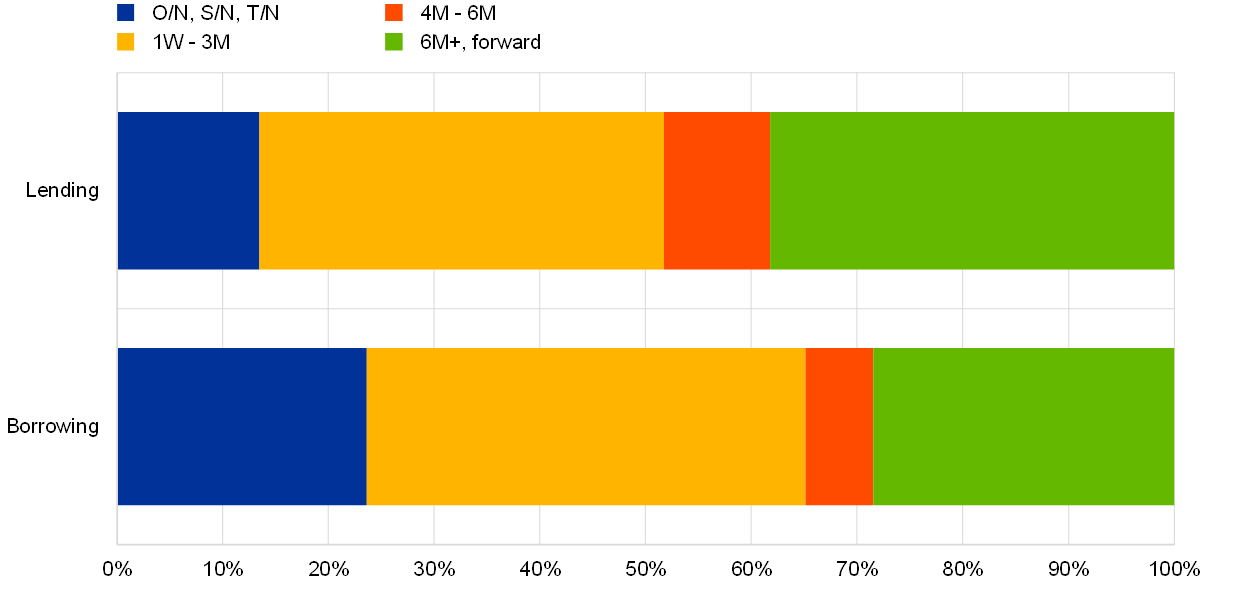

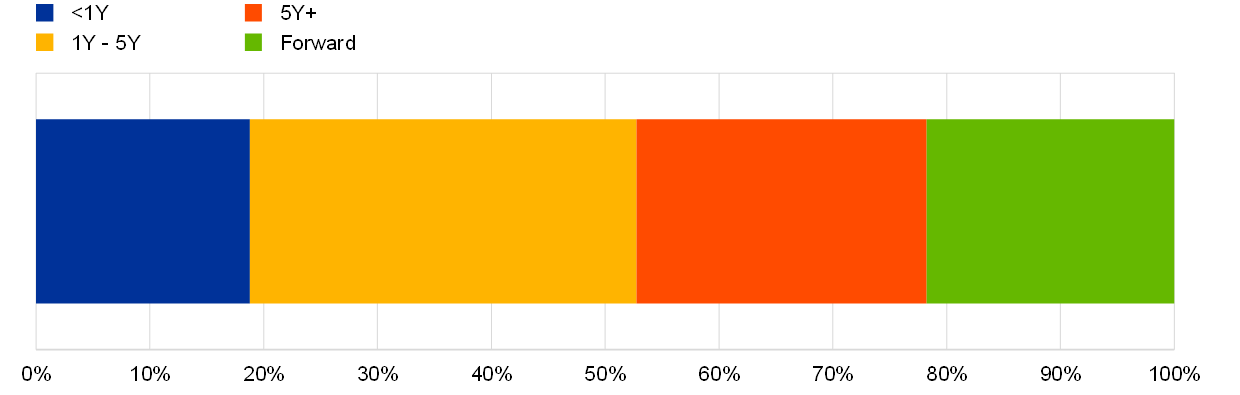

Outstanding volume per maturity

The stock of secured transactions is concentrated in the one-week to three-month maturity range, and accounts for around 40% of outstanding trades (see Chart 1.17). One-day maturity trades account for around 20% of outstanding amount, while the remaining 40% are trades with a maturity longer than three months and forward contracts. Over the review period the volume-weighted average maturity of secured transactions increased slightly, from around seven days in 2018 to over eight days in 2020.

Chart 1.17

Share of total outstanding amount by original maturity

(percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: The outstanding amount is a snapshot taken at 15 September 2020 in order to avoid reporting dates. The outstanding amount transforms the daily transaction volumes (flows) into a stock variable based on maturity dates.

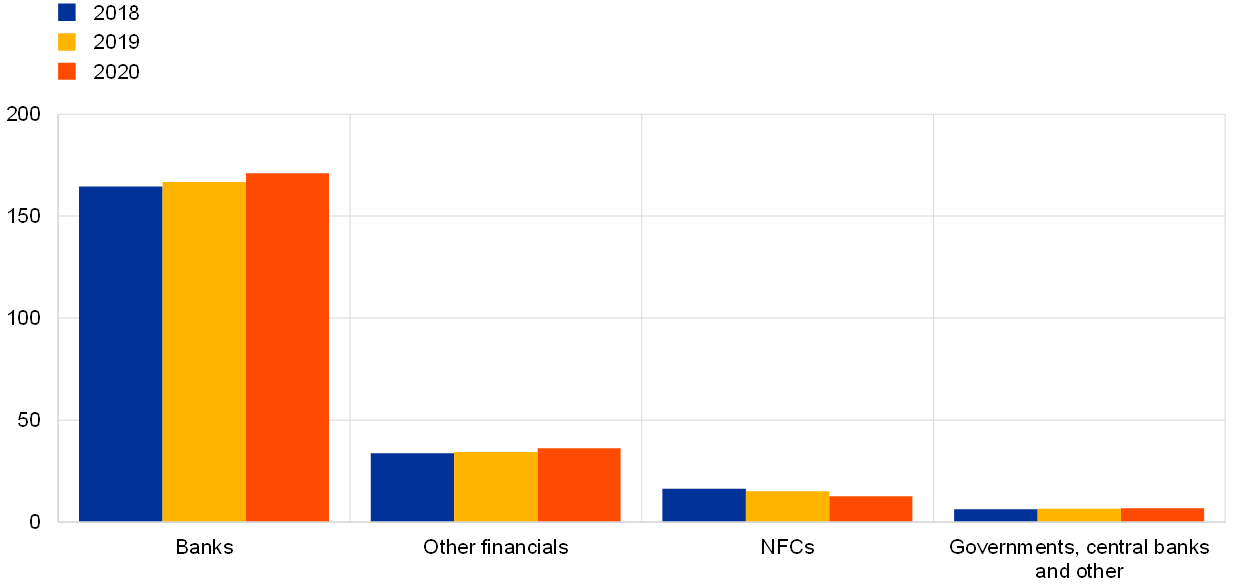

1.5 Counterparties

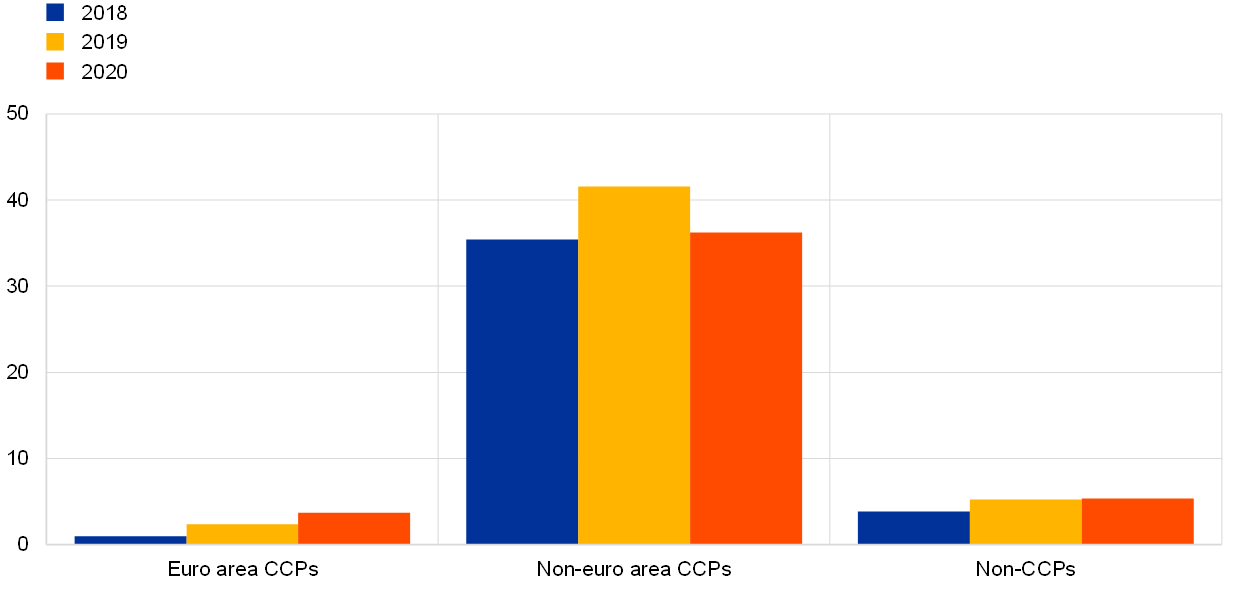

CCP clearing

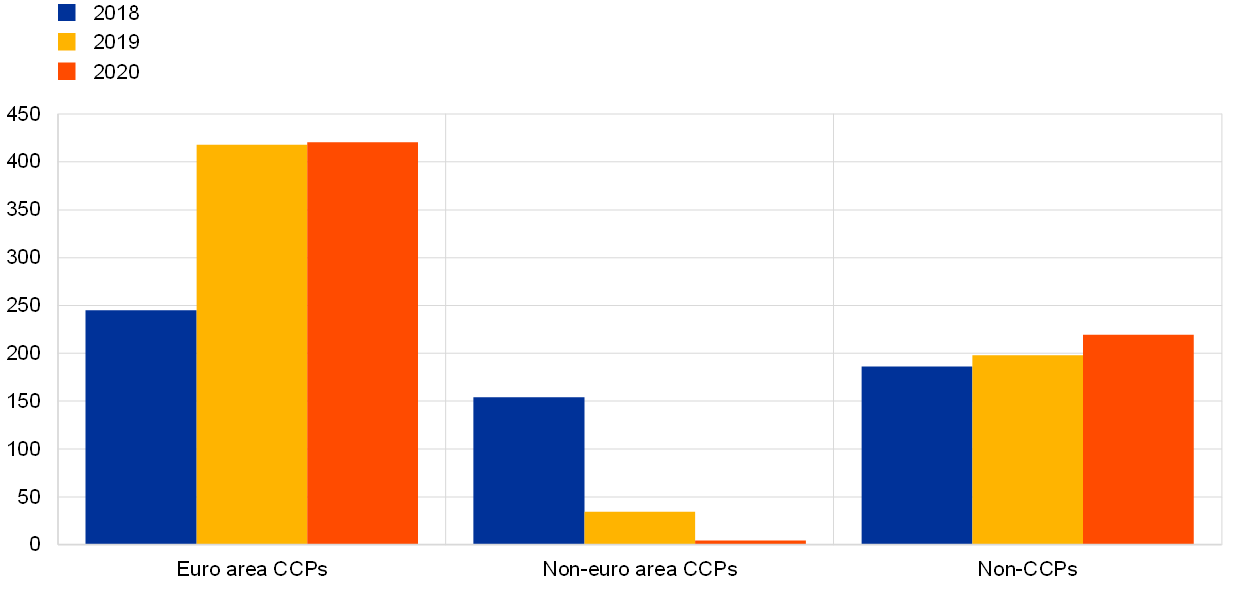

Around 70% of secured transactions were centrally cleared (see Chart 1.18). The remaining share was traded bilaterally through direct trading or via brokers. The analysis shows equivalent shares of CCP-cleared business in both borrowing and lending transactions.

Secured transactions were cleared via three major CCPs: LCH SA in France, CC&G in Italy and Eurex Clearing in Germany. During the review period, LCH moved their RepoClear business from LCH Ltd in the United Kingdom to LCH SA in France[7]. The move took place in February 2019, during the process of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU, which was completed in January 2020. LCH suspended the clearing of euro repo in LCH Ltd from 20 March 2020 onwards.

Chart 1.18

Secured transaction volumes per counterparty type and location

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Average daily volume of paid and received transactions.

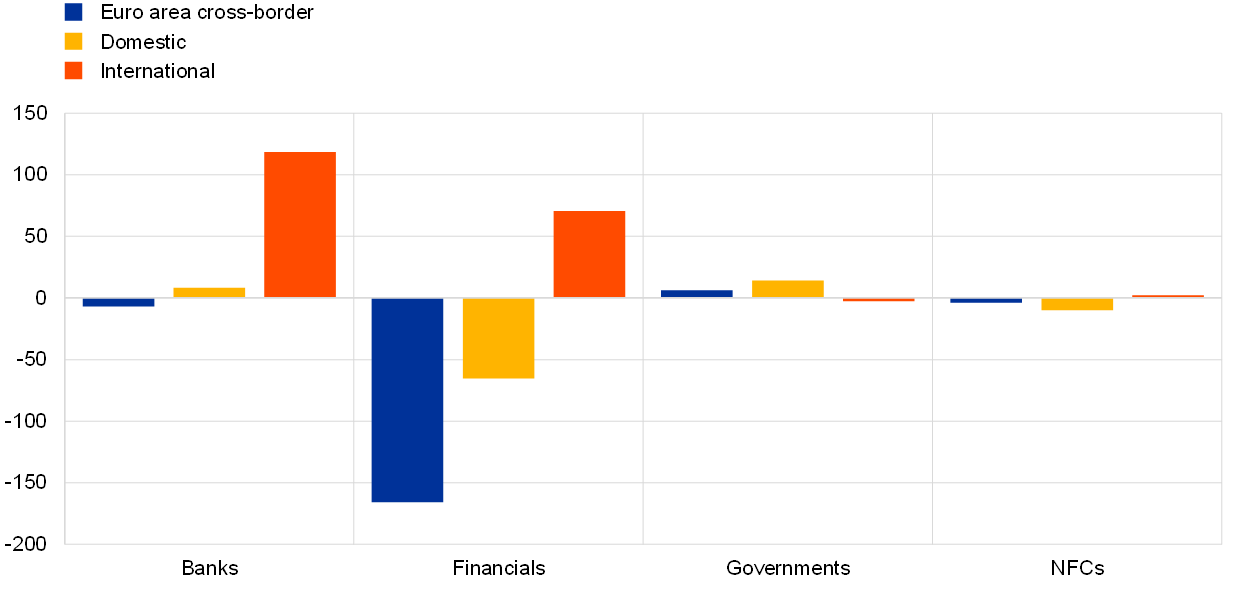

Flows by sector

Around 30% of trades are not centrally cleared – this share increased slightly over the course of the review period (see Chart 1.19). Banks have traditionally accounted for the largest share of this volume of bilateral transactions (41% in 2019). However, secured bilateral trading with investment funds, MMFs and insurance companies increased notably in 2020. This activity represented 39% at the end of 2020 as opposed to 32% the previous year. Taken together, these counterparties have now almost overtaken banks as the largest counterparty sector within bilateral trading. The increase in activity is consistent with a desire to hold more liquid instruments and higher cash buffers since the COVID‑19 pandemic began. MMFs and investment funds tend to be net cash lenders, using the secured segment to place cash. Insurance companies are generally net borrowers of cash in the repo segment.

Chart 1.19

Bilateral secured transactions by counterparty sector

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Note: Only non-CCP trades. IFs – investment funds, MMFs – money market funds, ICs – insurance companies. Government category consists of both general government and central banks. Confidential values are hidden. Average daily transaction volumes are plotted at a bi-weekly frequency.

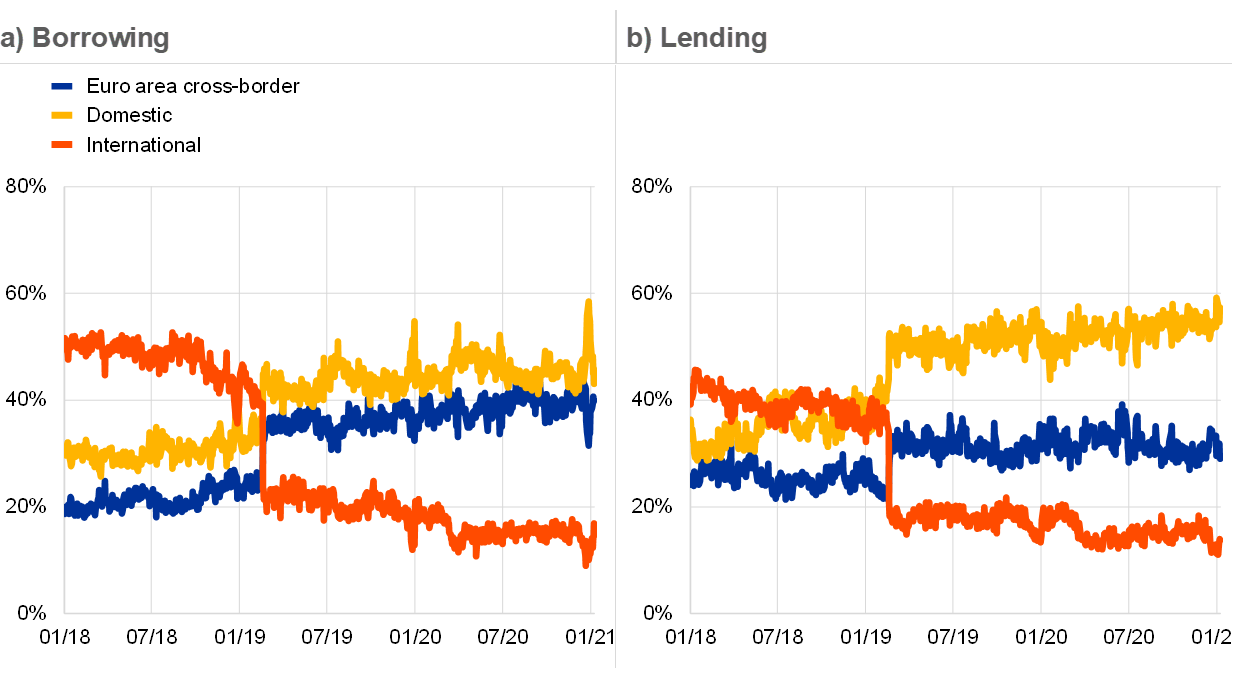

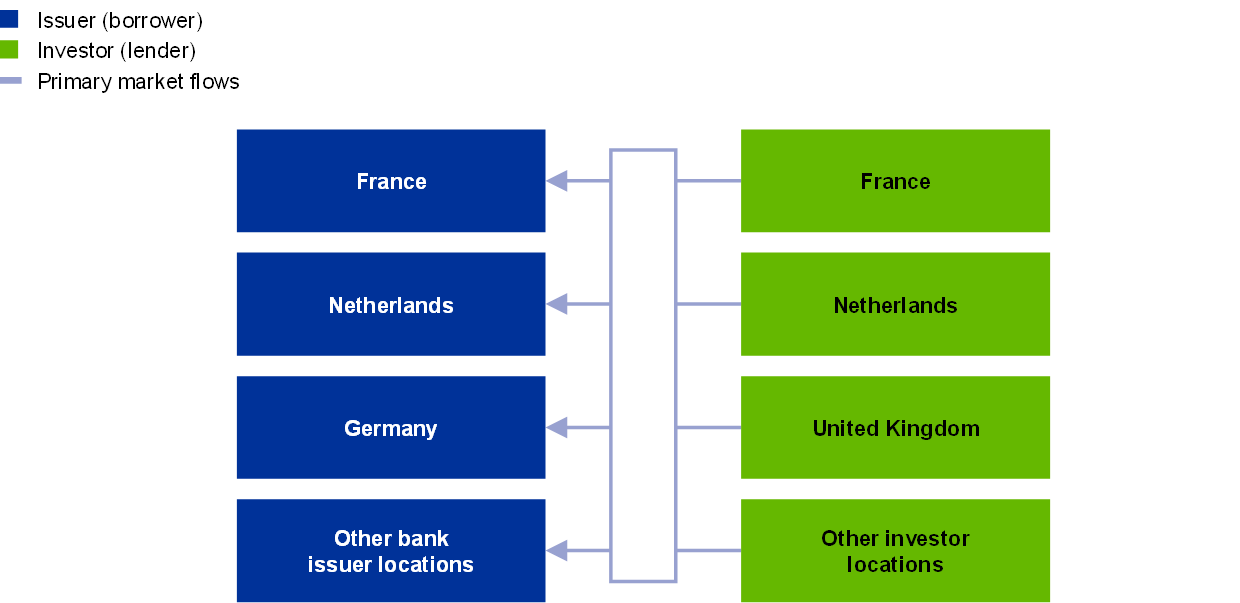

Flows by jurisdiction

There was a significant increase in the share of secured transactions executed in the euro area over the review period (see Chart 1.20). This may be largely attributed to the relocation of LCH’s RepoClear service from the UK to France, leading to an increase in domestic and cross-border transactions within the euro area. This move away from international counterparties has also been seen in non-cleared transactions. Euro area trading now accounts for most of the trading in both the cleared and the bilateral segments.

Chart 1.20

Secured transactions by counterparty location

(percentages)

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: A large reduction in international trades was observed on 19 February 2019.

2 The unsecured segment

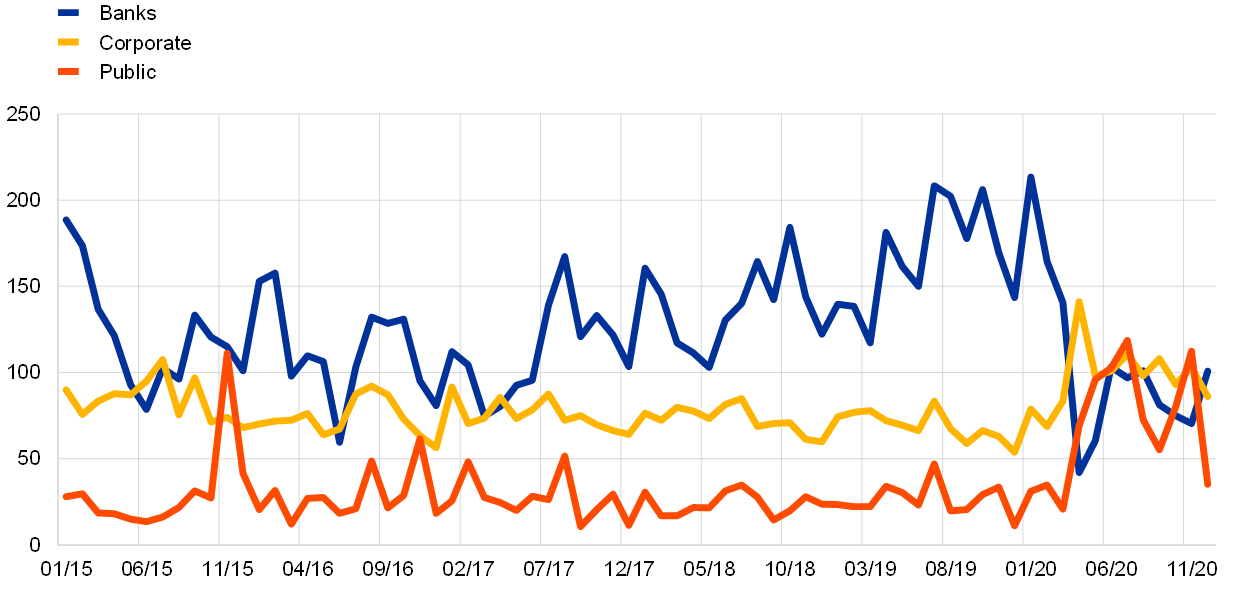

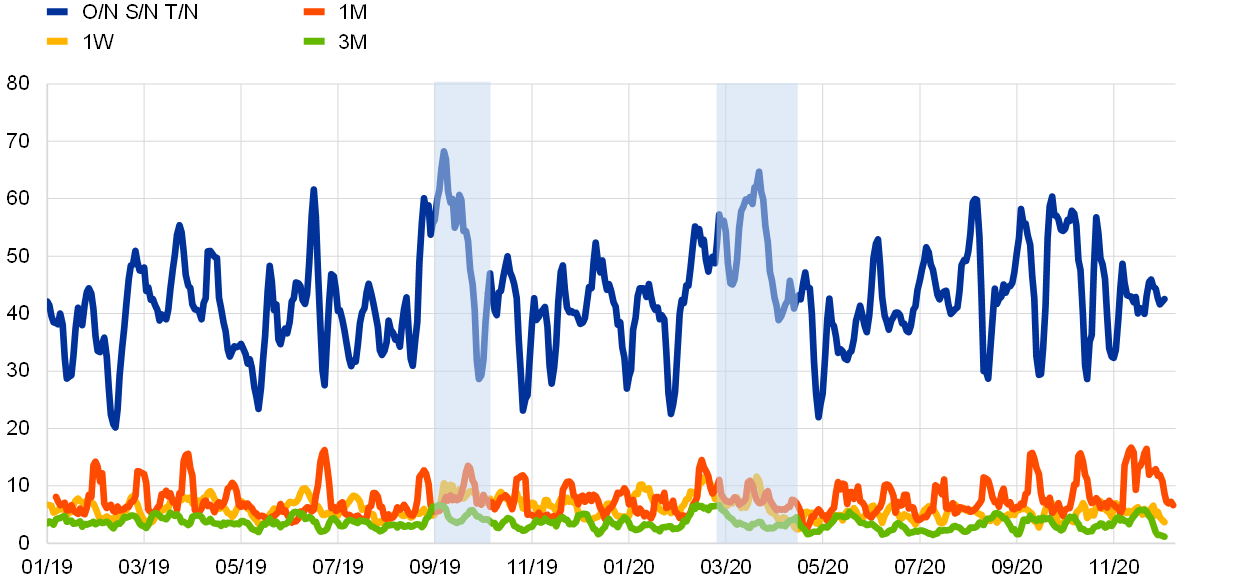

Activity in the unsecured segment has remained subdued but stable over the last two years, with a trading shift towards shorter maturities during the pandemic. The disruption in unsecured trading in the longer tenors during COVID‑19 has been driven largely by temporary tensions in the issuance of STS. Arbitrage opportunities in the FX swap segment have also been mentioned as a possible reason.

Owing to the high level of excess liquidity and the forward guidance, unsecured rates have gradually moved below the DFR for the shorter maturities. The euro short-term rate (€STR), which includes overnight borrowing transactions with banks and non-banks, has also edged below the DFR since its initial publication in October 2019. As non-banks do not have access to the Eurosystem’s deposit facility they tend to trade with euro area banks in order to “park” their excess liquidity. Since euro area banks need to cover the regulatory costs associated with the acceptance of unsecured deposits from non-banks, this trade pattern has led to the €STR staying stable at 5‑6 basis points below the DFR also throughout the pandemic crisis.

The stability of unsecured rates with short tenors during the pandemic has stood in contrast to the sharp and persistent rise in term rates and EURIBOR. Commercial paper rates also rose quickly as demand for STS paper from MMFs froze at the peak of the pandemic. As the issuance of commercial paper is economically equivalent to the collection of unsecured deposits (i.e. their rates embed risk premia to compensate for credit risk of borrowers), the relevant transactions fall within the economic reality that EURIBOR seeks to measure. Therefore, tensions in the commercial paper market were also visible in the unsecured term rates. Moreover, the increase in three-month LIBOR during the pandemic created an incentive to borrow funds in the euro unsecured market and swap these into US dollars, which resulted in further upward pressure on three-month EURIBOR. The impact of the STS and FX swaps segments on EURIBOR was amplified by the usual low levels of term unsecured trading activity.

Both the Eurosystem and the Federal Reserve System reacted decisively to the tensions in financial markets – tensions which extended well beyond the term money market. Central banks’ policy interventions effectively eased the liquidity strains observed in the spring of 2020 and supported market functioning by providing ample liquidity to banks. These interventions prevented self-reinforcing dynamics from taking hold in key financial market sectors, such as investment funds and MMFs, and at the same time kept unsecured turnover low as market funding was to a large extend replaced by central bank funding. EURIBOR has continued to decline in recent months and is currently at historically low levels, below the DFR. The yield curve in the unsecured money market has flattened significantly, even in comparison with the pre-pandemic period.

2.1 Volumes

2019‑20 trends

The unsecured segment represented 14% of euro money market turnover in 2020, predominantly reflecting banks’ borrowing transactions with non-banks (see Chart 2.1). Volumes in the money market have remained relatively robust since the GFC, supported by the increased participation of non-banks. The Eurosystem’s APPs have been increasing the amount of liquidity held outside the banking system when assets are acquired from counterparties different than euro area banks. These entities place a large part of the cash received from the Eurosystem back with their euro area counterparts to access the central bank balance sheet and, as a result, activity in both the unsecured and secured segments increased. Only 15% of volume was due to interbank activity within the euro area.

From a historical perspective unsecured activity notably declined, as the bulk of money market transactions shifted to the secured segment where centrally cleared solutions prevailed. The ample liquidity and the regulatory costs[8] associated with unsecured trading resulted in a continued preference by counterparties – especially banks – for secured trades.

Chart 2.1

Market share per segment

(EUR billions)

Sources: Panel (a) – ECB (euro money market survey) until 2016 and ECB (MMSR) from 2016 onwards; Panel (b) – ECB (MMSR).

Notes: Average daily transaction volumes. “FX” refers to the Foreign Exchange segment, while “OIS” refers to the Overnight Index Swap segment. Panel (a) includes only interbank counterparties and CCPs; Panel (b) includes all reported counterparties. The bars show euro money market survey data for 38 overlapping reporting agents and retropolated data for the 14 MMSR reporting agents not covered in the survey. The retropolation increases the series by a fixed proportion representing the 14 missing reporting agents’ market share at Q3 2016 (15% of the unsecured segment). Two confidential datapoints have been interpolated. The OIS segment excludes novations in MMSR data.

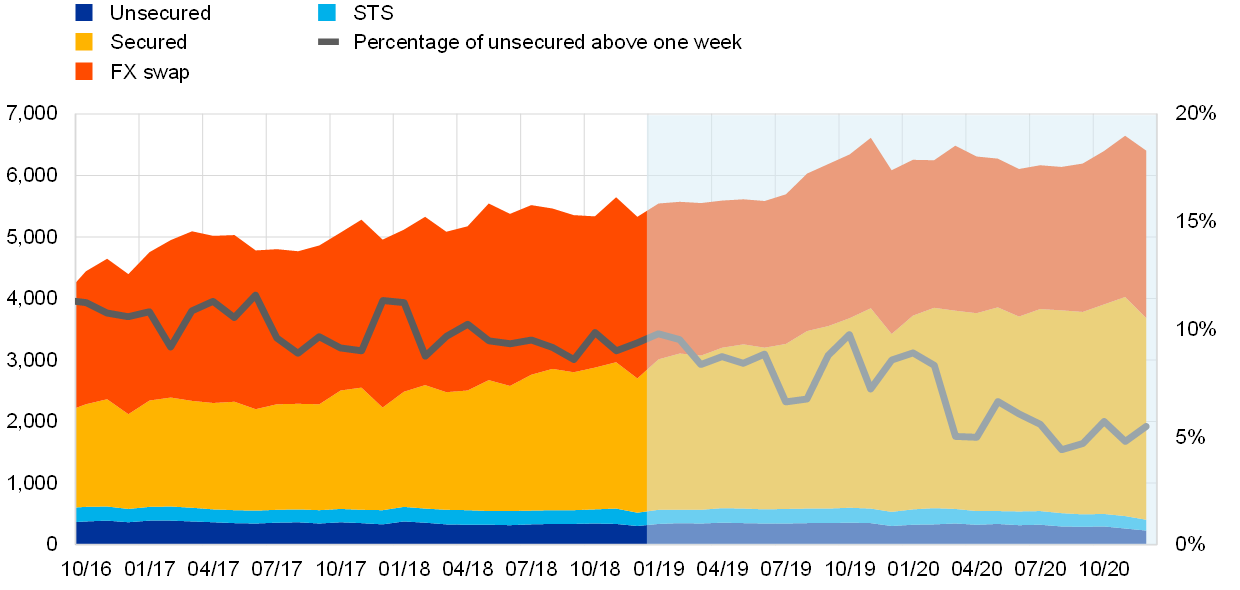

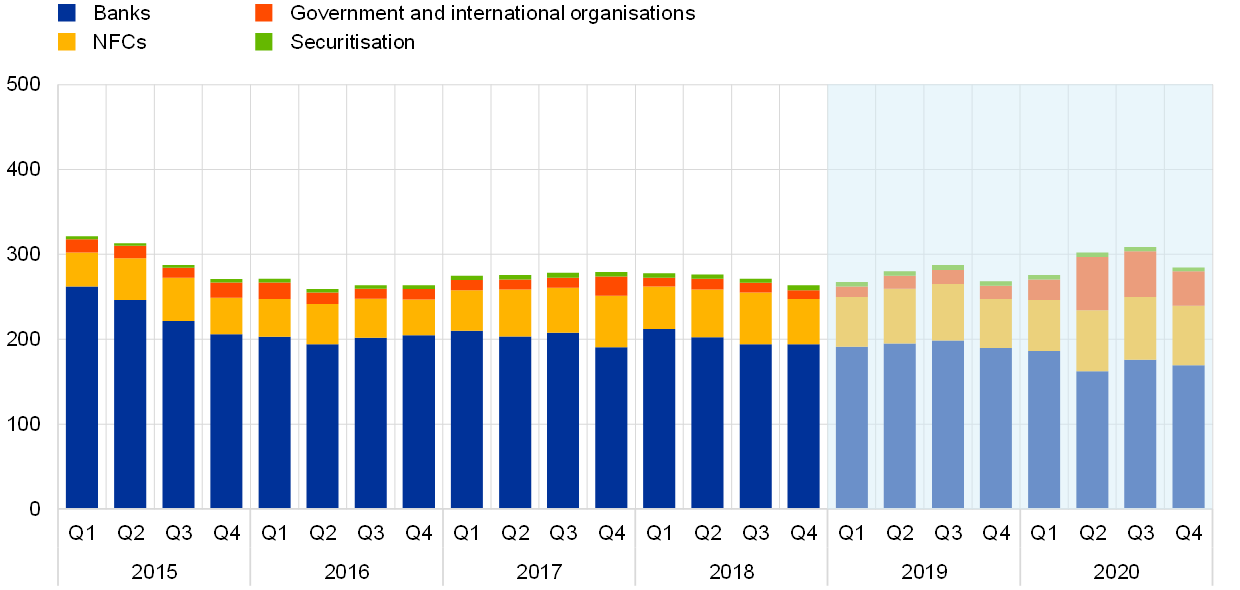

Activity in the unsecured segment has remained subdued but stable over the last two years, with a trading shift towards shorter maturities during the pandemic (see Chart 2.1 above and Chart 2.2). The outstanding volume in the unsecured segment was €326 billion in the period 2019‑20, with a daily average transaction volume of €140 billion. During the pandemic, short-term unsecured transactions have increased while volumes in longer tenors have shrunk. Unsecured transactions above one week represented 5% at the end of 2020, compared with 8% before the pandemic and 10% two years earlier.

The very low volumes of transactions in the term unsecured market led to a sharp rise in EURIBOR fixings during the peak of the COVID‑19 crisis. The reduction in EURIBOR actual unsecured transactions (Levels 1 and 2) at the peak of the COVID‑19 crisis forced the rate calculation to rely more on expert judgement and internal models for credit risk (Level 3). According to EMMI data, the contribution from Level 3 increased from 71% of the total in January 2020 to 82% in March 2020 for three-month EURIBOR, in line with the decrease in term unsecured turnover. Furthermore, the increase in LIBOR rates also exerted pressure on EURIBOR fixings because it was more convenient to borrow funds in euro and swap them in US dollars.

Chart 2.2

Outstanding amount borrowed and lent by euro area banks

(left-hand side: EUR billions, right-hand side: percentages)

Sources: ECB (MMSR for Unsecured and Secured data), CSDB for STS data.

Notes: “Unsecured” represent the outstanding amount borrowed and lent by MMSR banks, excluding any short-term debt instruments. The line shows the monthly average share of unsecured deposits transaction volume with maturity above one week. “Foreign exchange swap” represents buying and selling the EUR/USD currency pair. “STS” data refer to the outstanding amount issued or held by euro area banks (only in EUR currency). Tenors up to one year. The stacked areas show the amounts outstanding on the last day of each month.

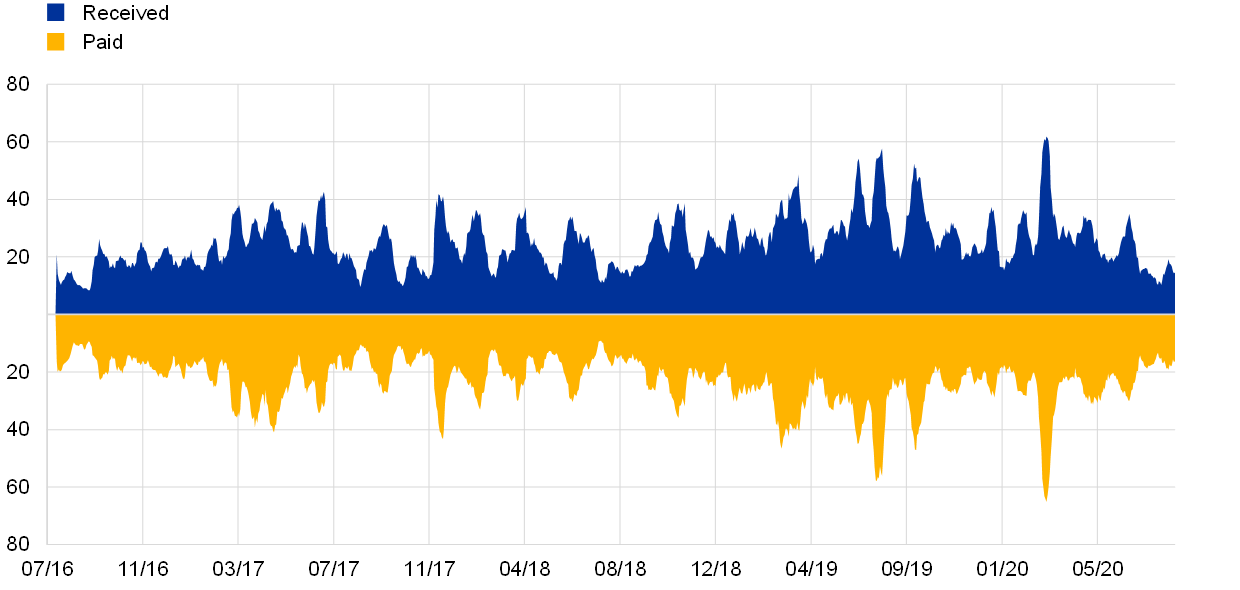

Borrowing transactions dominated activity by euro area banks in the unsecured segment, with banks channelling the excess liquidity to the Eurosystem as excess reserves or by using the deposit facility (see Chart 2.V.3). Borrowing volumes were significantly larger than lending volume[9], which reflected the intermediary position of the largest euro area banks in the euro money market, channelling reserves from non-banks that do not have access to the Eurosystem deposit facility. Despite the notable increase in excess liquidity, overall borrowing in the unsecured segment did not rise significantly, showing the declining role of this segment in the management of liquidity by large banks.

Interbank lending volumes remained marginal despite increasing temporarily following the introduction of the two-tier system in October 2019 (see Chart 2.3). Banks with insufficient excess liquidity to cover their two-tier system allowances borrow from banks which have liquidity which exceeds their own allowances. While most of this trading activity took place in the secured market[10], domestic liquidity redistribution also happened through the unsecured segment, especially in Germany. However, this increase was only temporary because banks receiving market liquidity achieved more favourable conditions in the TLTRO III monetary policy operations offered later by the Eurosystem.

Chart 2.3

Trends in daily transaction volume

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Note: Excludes commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes. Last date is 8 January 2021 for visualising year-end effects. Confidential values are hidden. The period under review is indicated by a light blue background.

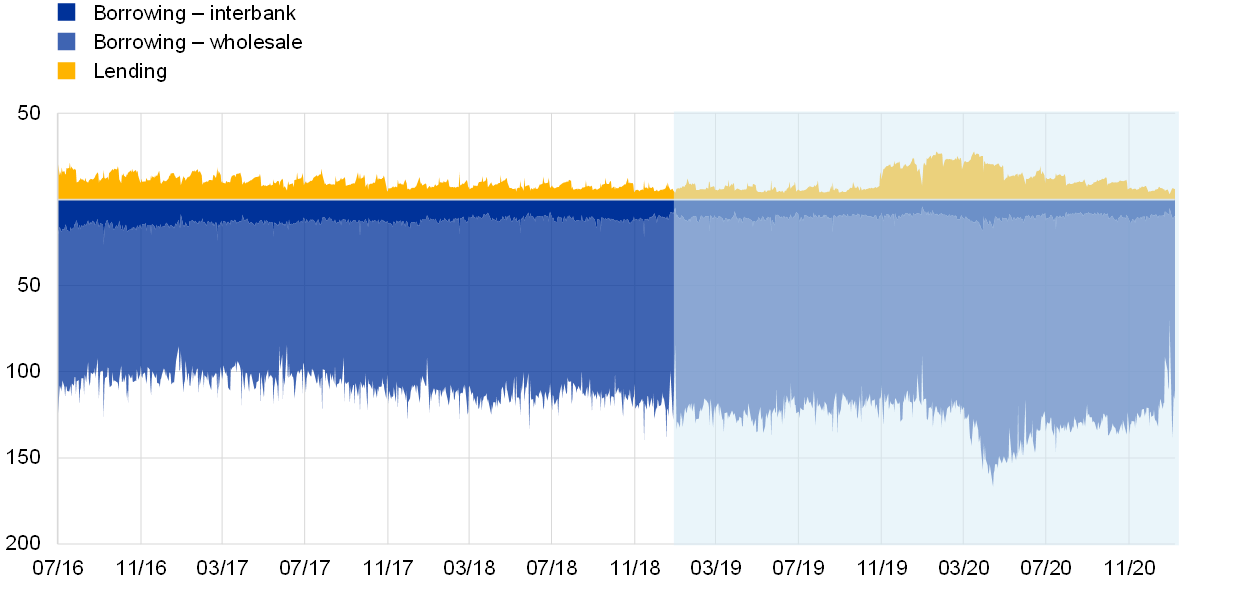

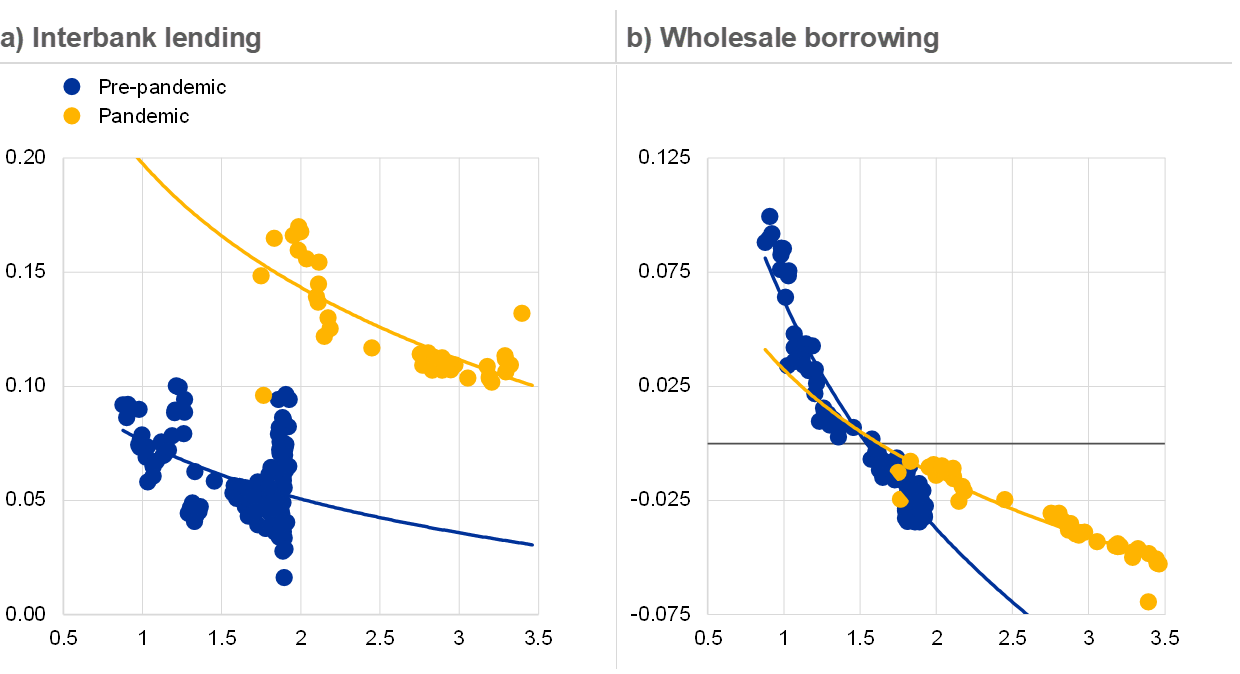

The relationship between excess liquidity and volumes

The data show that the liquidity injection is correlated with reduced interbank lending activity, while it is almost neutral for wholesale borrowing (see Chart 2.4). Prior to the pandemic, an increase in excess liquidity coincided, on average, with a notable decrease in unsecured lending volumes. Unsecured wholesale borrowing on average are not so responsive to the Eurosystem’s liquidity injections. Throughout the COVID‑19 crisis, a similar negative correlation between unsecured interbank lending volumes and the growth of excess liquidity has been observed. Nevertheless, the trend for excess liquidity is not strongly correlated with unsecured wholesale borrowing, either in the pre-pandemic period or during COVID‑19 times.

Chart 2.4

Correlation between unsecured volumes and excess liquidity

(y-axis: EUR billions; x-axis: EUR trillions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB (liquidity statistics published in wire services).

Notes: The blue dots represent the period before the COVID‑19 pandemic when excess liquidity was increasing (July 2016 – December 2018). The yellow dots represent the expansion of excess liquidity following the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic (March – December 2020). X-axis: weekly average euro excess liquidity; y-axis: weekly average unsecured O/N, S/N and T/N volumes.

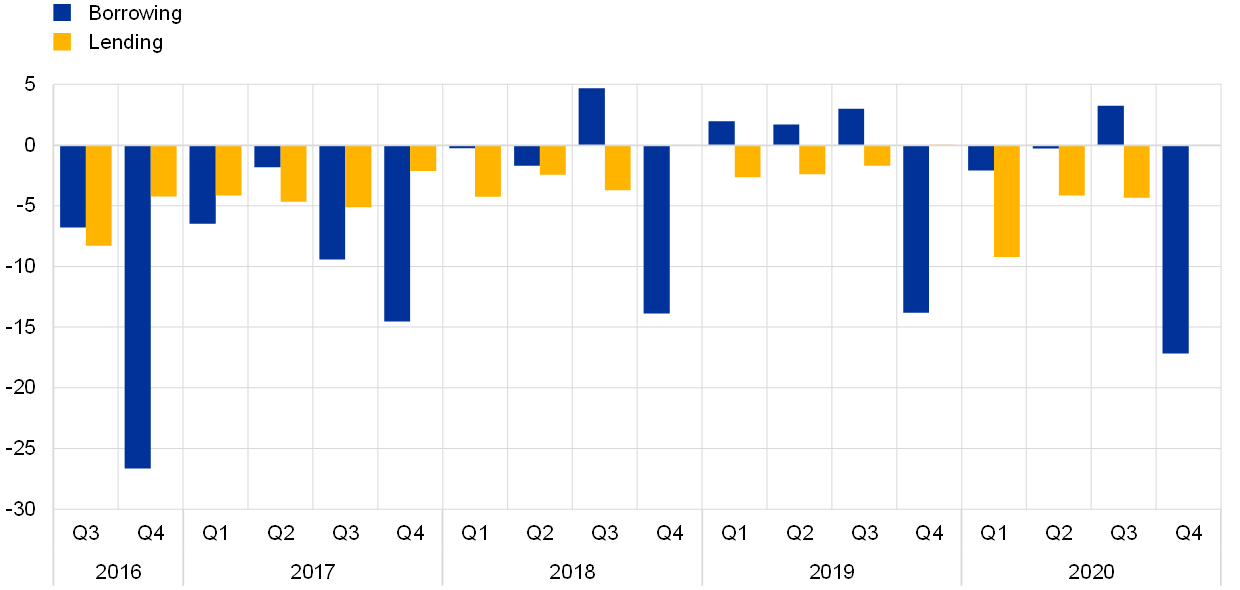

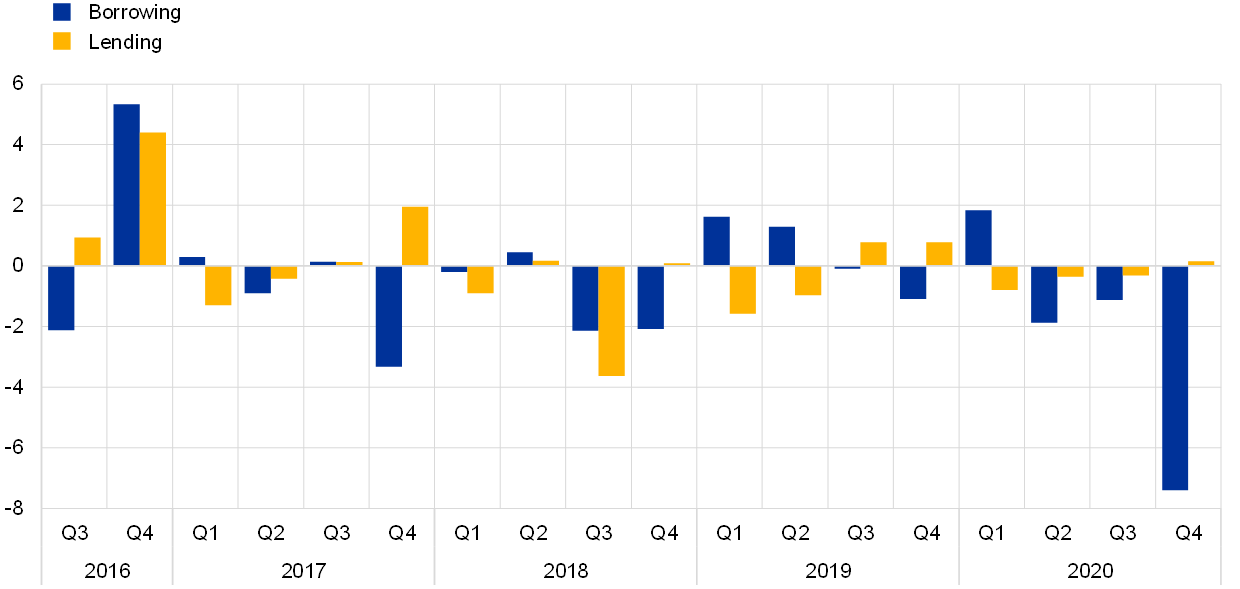

The relationship between reporting dates and volume

Borrowing transactions declined significantly at year-ends compared with quarter-ends, when the effects were less pronounced and occasionally resulted in increases in volume (see Chart 2.5). Transaction volumes usually drop at reporting dates for regulatory reasons, i.e. because of year-end “window-dressing” aimed at reducing the amount of bank levies and minimising regulatory costs. In the review period, borrowing transactions declined markedly at year-ends while interbank lending activities barely changed. By contrast, unsecured trading volumes showed the opposite trend over quarter-ends: while unsecured lending turnover always decreased to some extent, borrowing volumes rose at four out of six quarter-ends, albeit only slightly.

Chart 2.5

Changes in unsecured volumes for quarter-ends by transaction type

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: The change in transaction volume of the one-day maturity transactions (O/N, S/N, T/N) covering quarter-end and the prior working day. Excludes commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes.

2.2 Rates

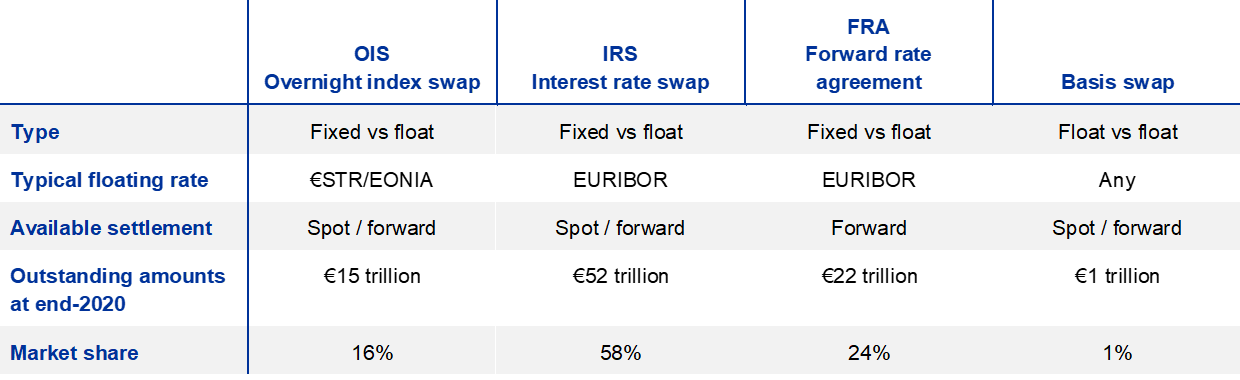

€STR, a new benchmark rate

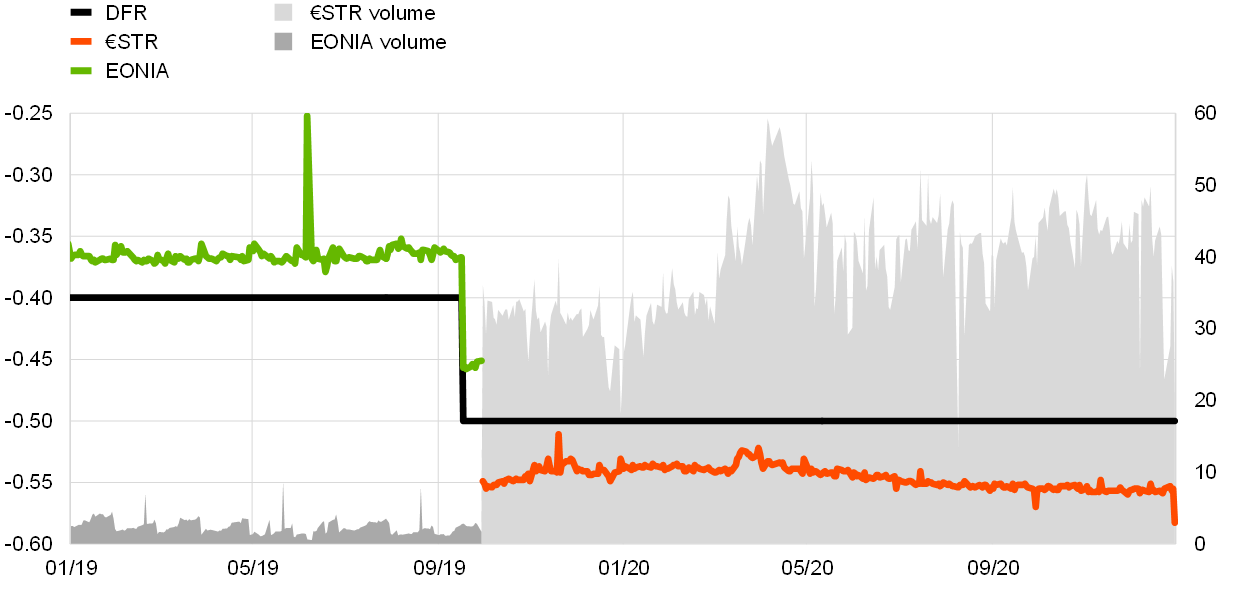

The €STR reflects the overnight cost of wholesale euro borrowing for euro area banks with financial counterparties – it was first published by the ECB on 2 October 2019. The rate was introduced to provide a robust reference rate for euro financial markets, is compliant with the International Organisation of Securities Commissions’ Principles for Financial Benchmarks and fulfils the three main criteria of a benchmark rate, i.e. rate accuracy, data sufficiency and rate representativeness. The €STR is published daily and is computed using a trimmed volume-weighted average rate for the eligible transactions settled on the previous TARGET2 business day.[11] In September 2018 the private sector working group on euro risk-free rates (WG RFR)[12] recommended that the €STR should replace the Euro Overnight Index Average (EONIA), which will be discontinued on 3 January 2022. However, the €STR has been the de facto reference rate for short-term rates in the euro area since October 2019, when the EONIA methodology was redefined as the €STR plus a fixed spread of 8.5 basis points.

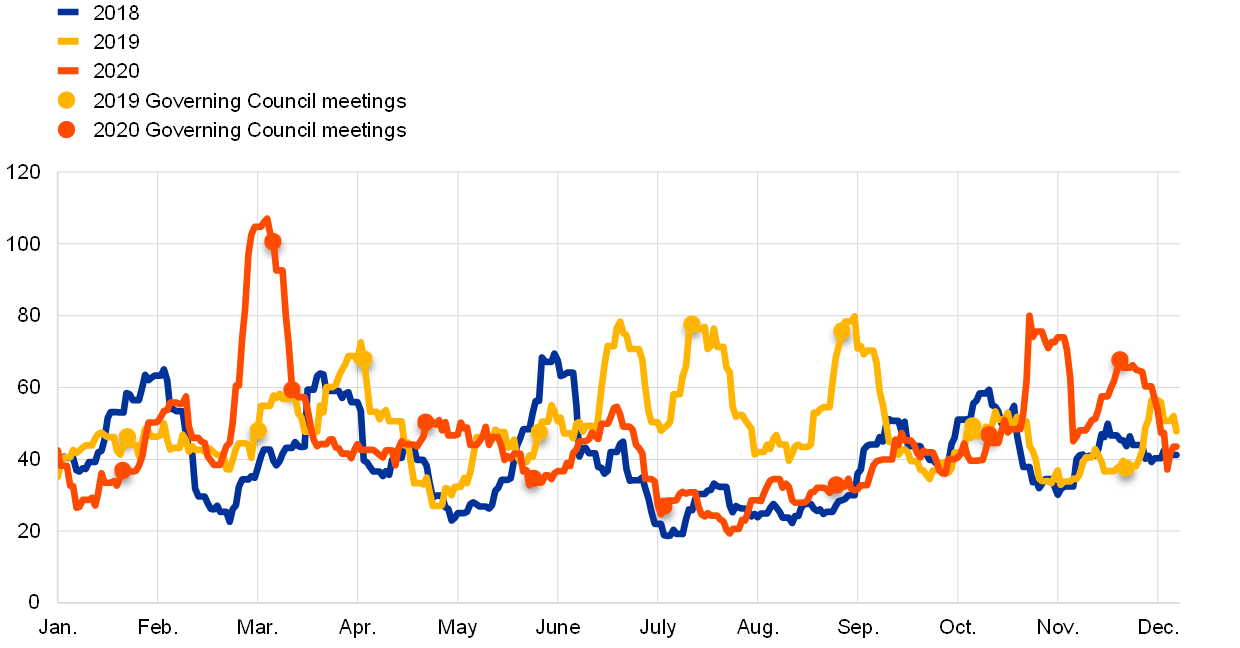

The €STR has been stable since its launch in October 2019 (see Chart 2.6). Since its inception, the €STR has fluctuated in a narrow range between ‑58.3 basis points and ‑51.1 basis points, while volumes have averaged €39.2 billion in a range between €13.5 billion and €59.3 billion. The relatively stable negative spread versus the DFR reflects the stable nature of overnight deposit pricing and the smoothing effect of trimming (which removes outlier transactions).

Three main trends can be identified since the €STR was introduced. First, when the two-tier system was implemented the €STR hovered at around ‑53 basis points (around 2 basis points above the levels registered in October 2019), reflecting the higher rates paid by some banks to borrow liquidity to fulfil their exempt tier. Volumes remained at an average of €30 billion, with limited daily deviations. Second, the COVID‑19 outbreak led to a deterioration in risk sentiment which caused MMFs to hoard cash in banks deposits and the €STR to rise slightly further up, reaching ‑52 basis points at around the end of March 2020. At the same time, volumes increased notably, reaching a peak of €59 billion on 6 April 2020. Third, the normalisation period saw a large increase in central bank balance sheets and improved risk sentiment (since May 2020), when the €STR averaged ‑55 basis points in the second half of 2020, with an average volume of €42 billion.

Chart 2.6

ECB unsecured benchmark rate and volume

(left-hand side: percentages, right-hand side: EUR billions)

Source: ECB, ECB calculations.

Notes: Until 1 October 2019 the ECB benchmark rate was EONIA, representing the overnight interbank lending unsecured activity. Afterwards, the ECB benchmark rate became the €STR, representing the overnight borrowing by euro area banks from all counterparty types in the unsecured segment.

2019‑20 trends

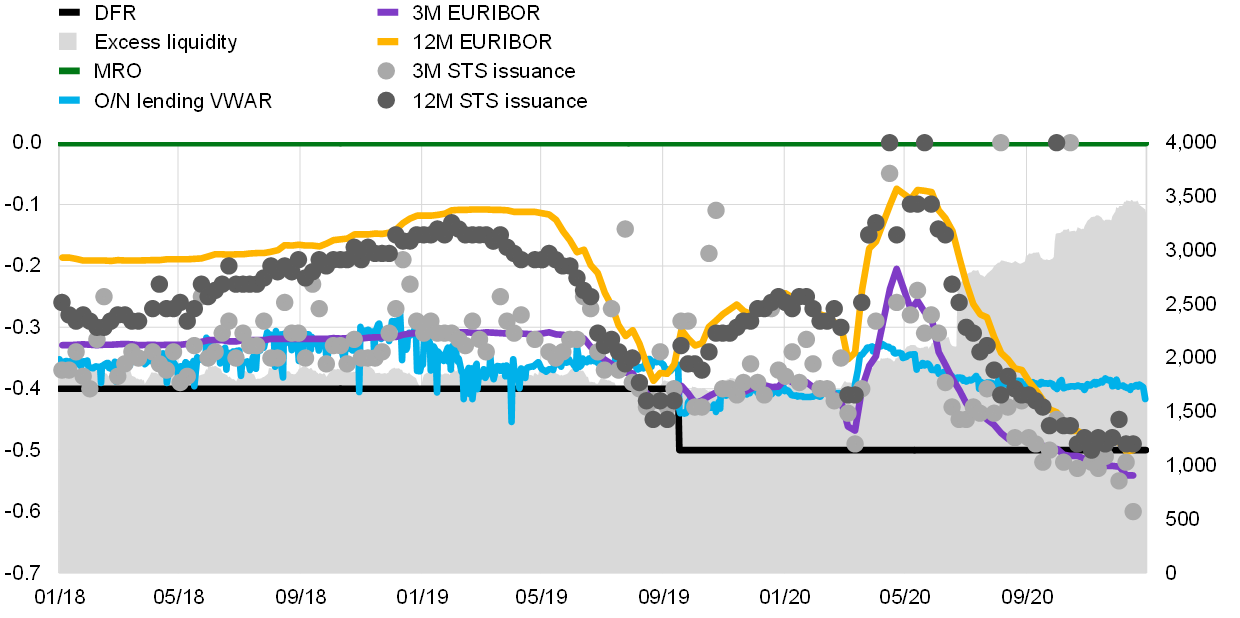

Overnight borrowing rates remained broadly stable, hovering at around 5‑6 basis points below the DFR, while lending rates, especially those for longer maturities, soared during the COVID‑19 crisis. As mentioned in the previous section, overnight borrowing costs remained anchored to the DFR and were largely unaffected by the main events which took place during the period under review. The low dispersion across short maturities borrowing rates stood in contrast to developments in term rates (especially those for lending transactions) as reflected in EURIBOR[13], which increased considerably at the beginning of the pandemic. Interbank overnight lending rates were also affected by the crisis, with the volume-weighted average rate increasing by 7 basis points during the market tensions in March.

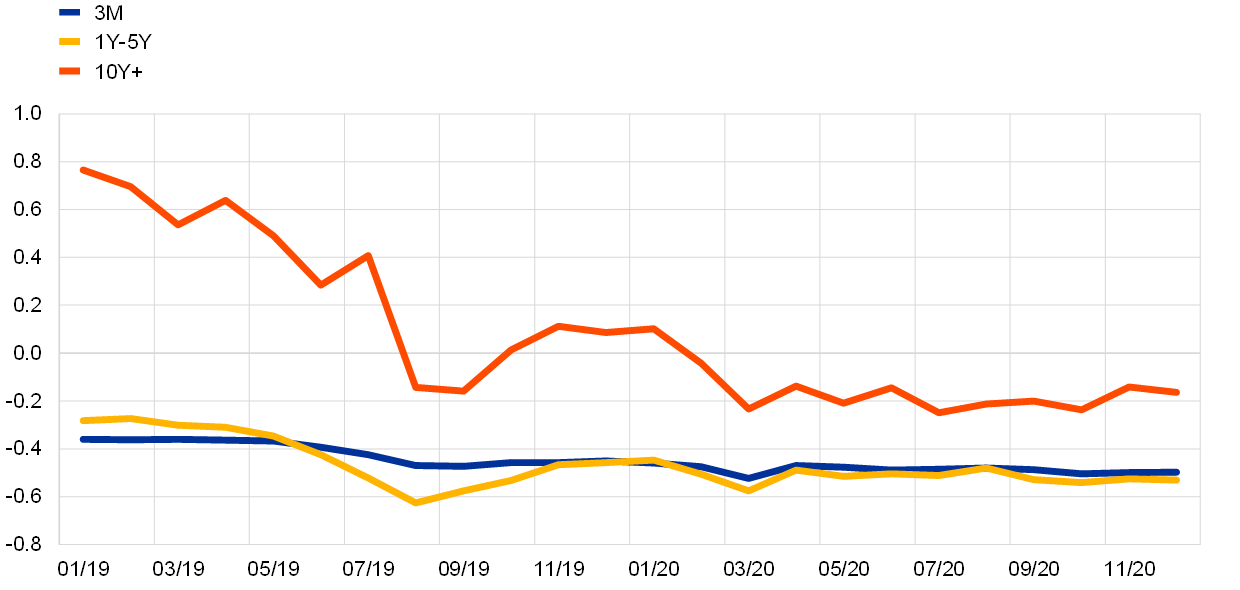

The rise in EURIBOR pointed to tensions in other segments of the money market (see Chart 2.7). At the end of April 2020, rates in the three-month and twelve-month maturities reached ‑20 basis points and ‑7 basis points respectively and were substantially higher than their pre-pandemic levels. Movements in term unsecured trading were largely driven by three factors. First, arbitrage opportunities in the FX swap segment caused an increase in three-month LIBOR during COVID‑19, which created a temporary incentive to borrow funds in the euro unsecured segment and swap these into US dollars. This resulted in upward pressure on three-month EURIBOR. Second, the low levels of market liquidity at longer horizons forced the panel banks under the EURIBOR’s hybrid methodology to also rely on expert judgement. The latter was likely based on estimates of credit risk derived from internal models. Third, as commercial paper rates are used as a Level 1 contribution for the pricing of EURIBOR under the hybrid methodology, tensions in the commercial paper market also affected rates in the term unsecured money market.

Chart 2.7

EURIBOR and O/N lending unsecured rates vis-à-vis STS rates

(left-hand side: percentages; right-hand side: EUR billions)

Sources: STS data (Banque de France), ECB(MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: “STS” stands for short-term debt issuance based on NEU CP data. EURIBOR refers to the average interest rate at which euro area banks offer short-term lending in the interbank unsecured segment. O/N lending is a volume-weighted average unsecured rate from MMSR.

The unsecured term rates respond both to expected changes in the Eurosystem’s policy stance, such as expectations of a DFR cut in 2019, and to easing measures introduced by the Eurosystem in March 2020. The yield curve inverted briefly, amid significantly lower term rates, in August 2019 when markets were pricing in the very high likelihood of an imminent DFR cut (September 2019). After the rate cut the curve’s shape gradually normalised until the COVID‑19 outbreak, when longer-term rates started to increase visibly amid the market stress. Starting from the end of April, the expanded Eurosystem measures implemented in response to the pandemic shock, combined with improved market conditions, brought significant relief to unsecured borrowing rates, which started to fall across maturities. After June the notable rise in excess liquidity led rates across the unsecured yield curve to drop below pre-pandemic levels, with the most notable declines recorded for term rates. Another example is the spread between overnight and twelve-month rates, which reached 29 basis points at the end of May 2020 compared to 10 basis points in January 2020. These developments were in line with what had been observed in other market segments, such as the commercial paper and certificate of deposit market, as reflected by EURIBOR’s dynamics.

The relationship between excess liquidity and rates

Liquidity injections during the COVID‑19 crisis have coincided with downward pressure on short-term unsecured rates (see Chart 2.8). The increase in excess reserves during the pandemic has been negatively correlated with both lending and borrowing rates. In the case of the borrowing rate, the negative correlation seems to have softened compared with previous periods of large liquidity injections between 2016 and 2018.

Chart 2.8

Correlation between the unsecured rate spread versus the DFR and excess liquidity

(y-axis: percentages; x-axis: EUR trillions)

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB (liquidity statistics published in wire services).

Notes: The blue dots represent the period before the COVID‑19 pandemic when excess liquidity was increasing (July 2016 – December 2018). The yellow dots represent the expansion of excess liquidity following the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic (March – December 2020). x-axis: weekly average euro excess liquidity, y-axis: weekly average volume-weighted average unsecured O/N, S/N and T/N rates’ spread versus the DFR.

The relationship between reporting dates and rates

Unsecured overnight rates exhibit seasonality at quarter-ends (see Chart 2.9). Close to regulatory reporting dates, banks apply more punitive prices for deposits. Their objective is to disincentivise borrowing transactions and reduce the size of their balance sheets in order to improve prudential ratios and optimise bank levies. As a result, unsecured borrowing rates regularly decline at quarter-ends and, sometimes, more significantly at year-ends. In the period under review this result could be observed in most quarters.

Chart 2.9

Unsecured rates’ day-to-day moves at quarter-ends

(basis points)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: The difference in volume-weighted average rates on the days covering quarter-ends and the prior working day. Only one-day maturity transactions (O/N, S/N, T/N). Excludes commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes.

The high level of excess liquidity in the system during the second half of 2020 exacerbated the quarter-end effect on the €STR. Elevated excess liquidity conditions, especially after the settlement of TLTRO III.4, incentivised reporting agents to reduce borrowing from the market at quarter-ends, minimising balance sheet costs. In this vein, the €STR dropped by 1.4 basis points to ‑57.1 basis points on 30 September, and by as much as 2.8 basis points to an all-time low of ‑58.3 basis points on 31 December 2020 – the largest month-end movement on record.

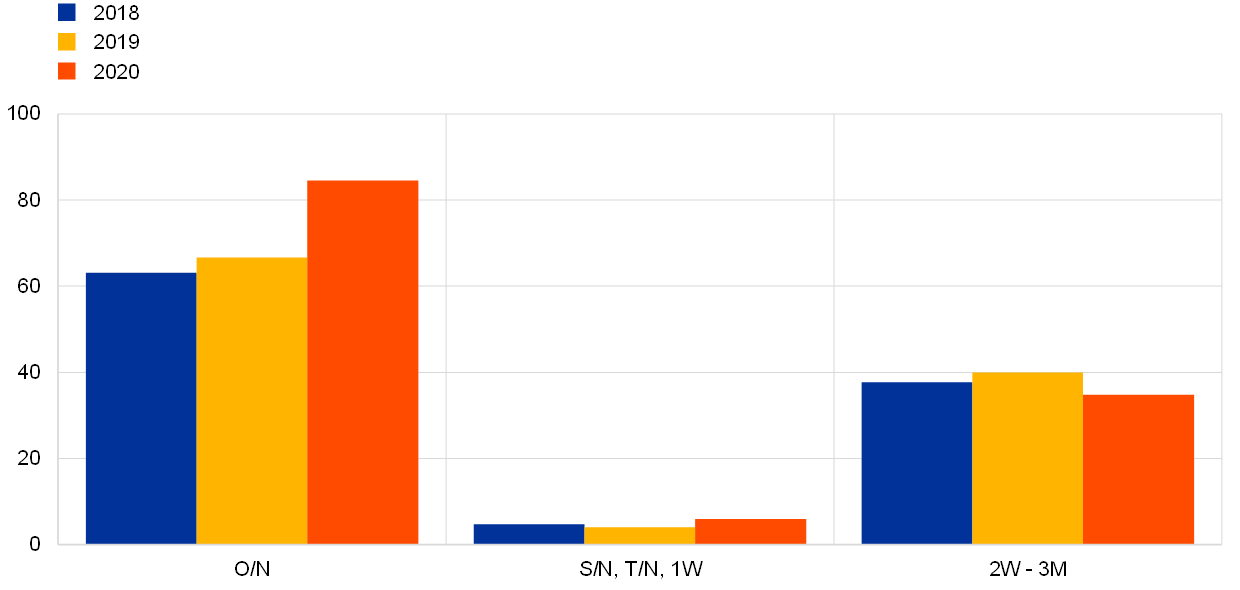

Yield curve

The yield curve in the unsecured segment steepened temporarily in March 2020 but by the end of 2020 the yield curve was lower and flatter than two years earlier (see Chart 2.10). The lowering of the curve was due to the DFR cut in September 2019, while the flattening was a consequence of the Eurosystem’s expansion of the provision of liquidity as a response to the tensions in financial markets due to the COVID‑19 crisis as well as the expectations for negative interest rates for a prolonged period. The flattening mainly affects the six-month to twelve-month maturity bucket. The Eurosystem’s increase of excess liquidity had a sustained downward effect on money markets in the euro area, affecting longer maturities in particular. EURIBOR continued to recede in the second half of 2020 and stood at historically low levels at the end of that year.

Chart 2.10

Yield curve

(left-hand side: EUR billions; right-hand side: percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: COVID‑19 represents the period 17‑23 March 2020, when the unsecured market experienced tensions. The remaining values are daily averages over the quarter. The right-hand side axis and the bars represent the average daily volume (STS data included) per maturity. The left-hand side axis and the lines represent the volume-weighted average rate per maturity.

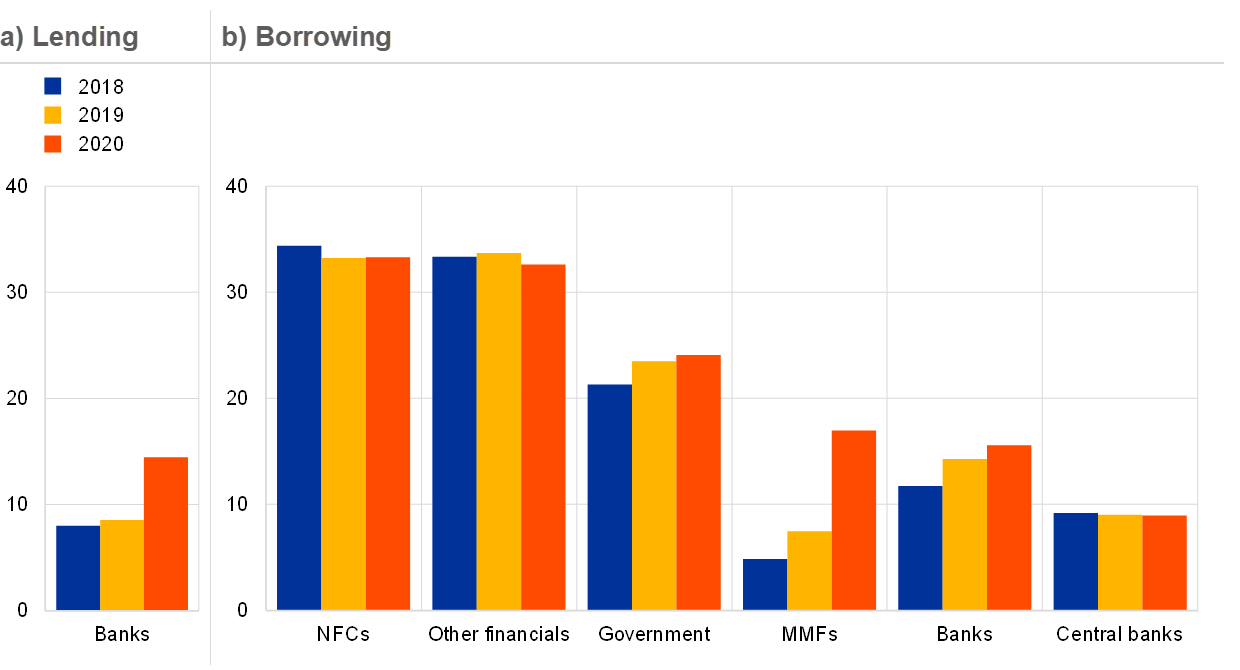

The yield curve exhibits segmentation on the trading counterparties (see Chart 2.11). Borrowing rates from NFCs are generally higher than those for counterparties belonging to the financial sector. Looking at the one-day maturity bucket, deposit trades with other financial institutions are, on average, around 4 basis points below the DFR, while trades with government entities and corporates show a positive spread versus the DFR. Transactions with NFCs have always been executed at higher rates than in the interbank market. Euro area banks reported deal rates above the DFR for trades conducted with NFCs as well as those with government entities. Nevertheless, amid increasing levels of excess liquidity, the spread between borrowing rates from financial institutions and NFCs tightened during 2020, from 25 basis points in the first quarter of 2020 to 15 basis points in the third quarter of 2020.

Chart 2.11

Unsecured yield curve per counterparty

(left-hand side: EUR billions; right-hand side: percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: The left-hand side axis and the bars represent the average daily volume per maturity. The right-hand side axis and the lines represent the volume-weighted average rate per maturity. The chart includes both borrowing and lending transaction volumes for banks. Only borrowing unsecured transactions with NFCs and other financial corporations are reported in MMSR. The sample covers transactions from 2019 to 2020. Confidential values are hidden.

2.3 Maturities

Transaction volume per maturity

Most unsecured transactions are executed overnight, accounting for 67% of the overall unsecured trades in 2020 (see Chart 2.12). These are deposits as well as call accounts or call money, i.e. money lent by banks that must be repaid on demand. There are no significant differences with regard to maturity distribution between borrowing and lending transactions, except for the fact that the turnover of the latter is much lower. The preference for short-term transactions has been even more pronounced during the COVID‑19 crisis.

Chart 2.12

Unsecured volumes by maturity over time

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: The chart shows borrowing and lending volumes. Commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes are excluded. Maturities above three months are hidden for reasons of confidentiality.

Outstanding volume per maturity

The stock of unsecured transactions is concentrated in the six-month to one-year maturity tenors (see Chart 2.13). In contrast to the distribution of transaction volume, one-day maturity trades only account for around 20% of outstanding volume, the remaining 80% being trades with a maturity longer than one week, including a large proportion of contracts for six months and beyond. Over the review period the volume-weighted average maturity decreased substantially, from nine days at the beginning of 2019 to five days at the end of 2020, in a trend that has continued since MMSR data was first produced in 2016, when the average maturity stood at ten days.

Chart 2.13

Share of total outstanding amount by original maturity

(percentages)

Source: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: The outstanding amount is a snapshot taken at 15 September 2020 in order to avoid reporting dates. The outstanding amount transforms the daily borrowing and lending transaction volumes (flows) into a stock variable based on maturity dates. Commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes are excluded.

2.4 Counterparties

Flows by sector

While the share of interbank activity remained very limited, unsecured borrowing activity increased slightly – from 10% to 12% – in the period under review (see Chart 2.14). The largest share of euro area banks’ unsecured borrowing transactions took place with NFCs and other financials, with each accounting for 25%. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that unsecured borrowing business with governments and MMFs increased notably between 2019 and 2020, as did interbank lending during the same period.

Chart 2.14

Unsecured transaction volumes by counterparty sector

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: Lending volume is reported only for bank counterparties in MMSR data. Commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes are excluded.

Activity with MMFs has increased since the March tensions surrounding COVID‑19. Focusing on borrowing transactions, MMFs have continued to increase their relative trading volume in the unsecured sector. During the second quarter of 2020, these represented 12% of total unsecured trading volume, compared with 4% at the end of 2018. The increase related partly to the dynamics which emerged during the COVID‑19 crisis, when MMFs opted to redirect funds away from holdings of commercial paper and certificates of deposit towards short-term money market (unsecured and secured) transactions, in order to increase their liquidity buffers.

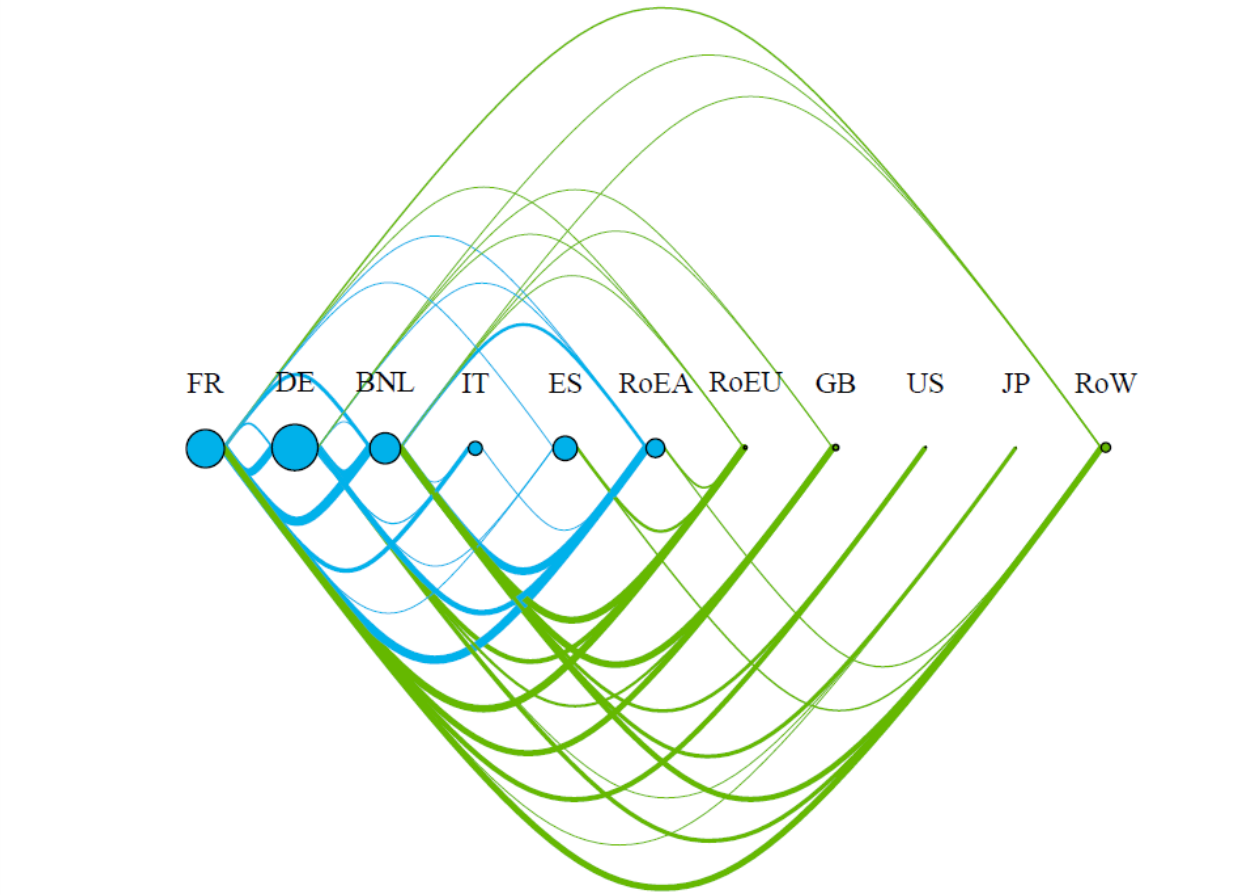

Flows by jurisdiction

Over time, excess liquidity tended to accumulate in specific banks located in a few euro area countries, independently of how the liquidity had originally been provided by the Eurosystem (see Chart 2.15). The liquidity provided through Eurosystem TLTRO III operations was more evenly distributed among euro area countries than had been the case for previous TLTRO series. However, Eurosystem APPs did not lead to a proportional increase in excess liquidity in the jurisdictions of the securities issuers. While the geographical distribution of purchases closely reflected national central banks’ (NCBs) share of the ECB’s capital key, more than half of the purchases were with counterparties belonging to banking groups whose head office was located outside the euro area. In addition, within the euro area the management of euro-denominated liquidity is concentrated in specific locations. For example, custodians and clearing institutions that process Eurosystem asset purchases are typically located in Belgium, Germany or France. Liquidity from the APP and PEPP placed in cash accounts may circulate further, while unused balances are likely to be swept into TARGET2 accounts at the end of the business day. As a result, excess liquidity tends to accumulate in specific banks of few euro area countries over time, seemingly independently of how the liquidity is provided by the Eurosystem. In addition, liquidity needs according to autonomous factors vary greatly between NCBs. Unsecured inflows into the euro area come either from entities operating in financial centres in Germany, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom or from foreign banks in the United States and Japan and international banks based in Poland. The main recipients of the liquidity are MMSR reporting banks in Germany, France and Benelux.

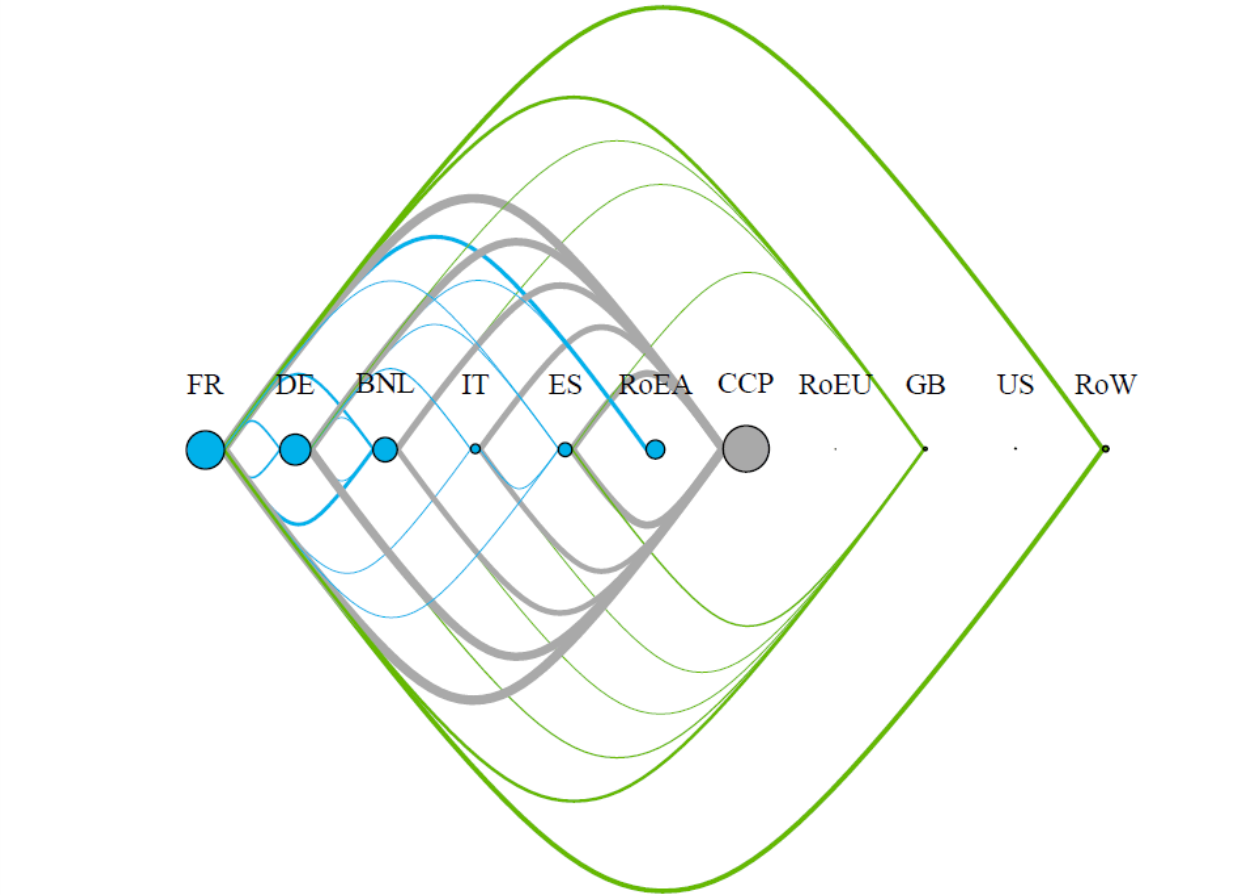

Chart 2.15

Overnight unsecured transaction volumes across jurisdictions

(nodes: total volumes per area, connections on the top: lending flows, connections on the bottom: borrowing flows)

Source: ECB (MMSR).

Notes: The chart shows borrowing and lending transactions. The blue lines represent flows within the euro area, the green lines represent international connections.

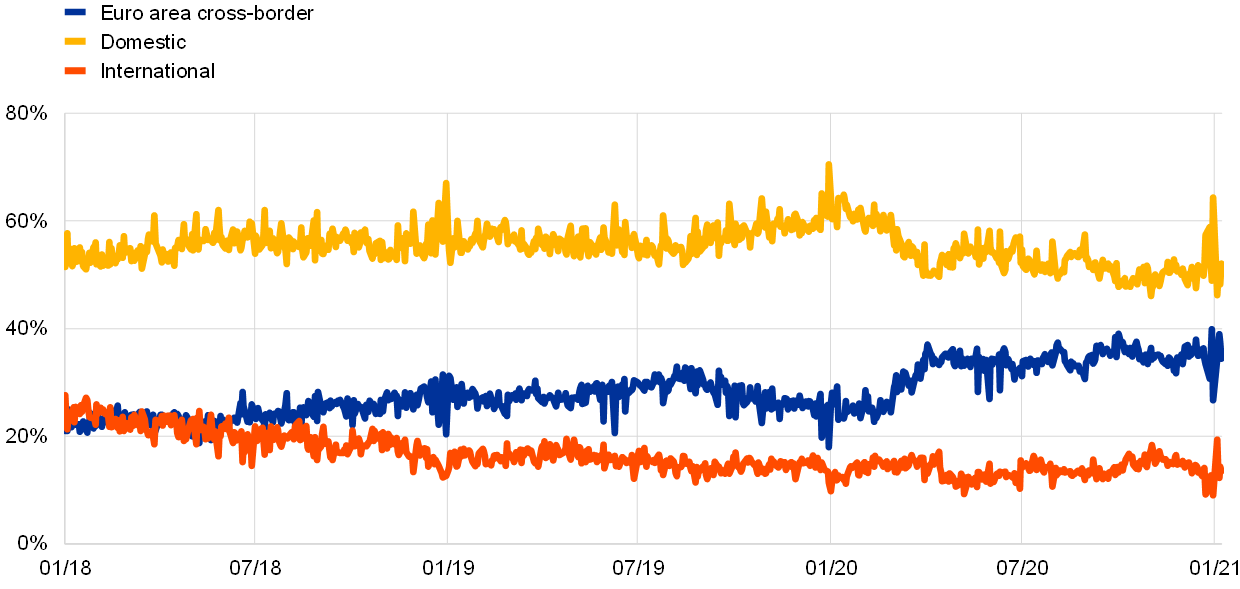

Cross-border trading has increased over the past two years (see Chart 2.16). In terms of borrowing, the share of volume traded between counterparties belonging to the same country oscillated between 50% and 60% in 2018 and 2019, while it declined to around 46% during 2020. Meanwhile, the share of euro area cross-border trading rose steadily after 2018, and especially in 2020, amid higher activity with MMFs located in Ireland, France and Luxemburg. On the lending side, the introduction of two-tier system led to an increase in the domestic share of transactions. German counterparties traded more actively in the interbank market in order to fill their exempt tiers – this happened mainly within banking networks (Verbünde), while similar patterns were not observed in other jurisdictions.

Chart 2.16

Unsecured borrowing transactions by counterparty location

(percentages)

Sources: ECB (MMSR), ECB calculations.

Notes: Cross-border flows are flows between non-domestic counterparties within the euro area, while international flows are flows across the euro area border. Only borrowing volumes are included. Commercial paper, certificates of deposit and floating rate notes are excluded.

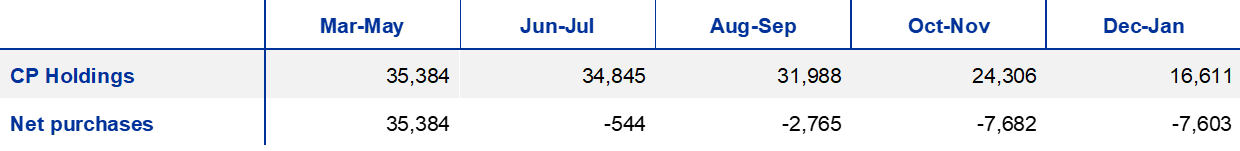

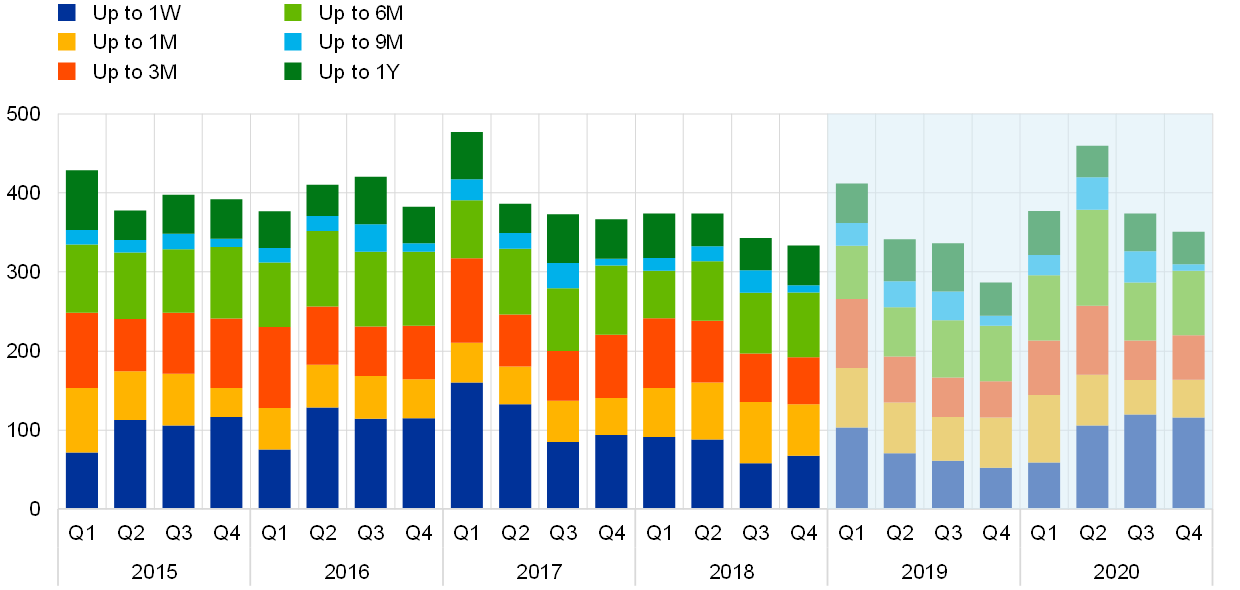

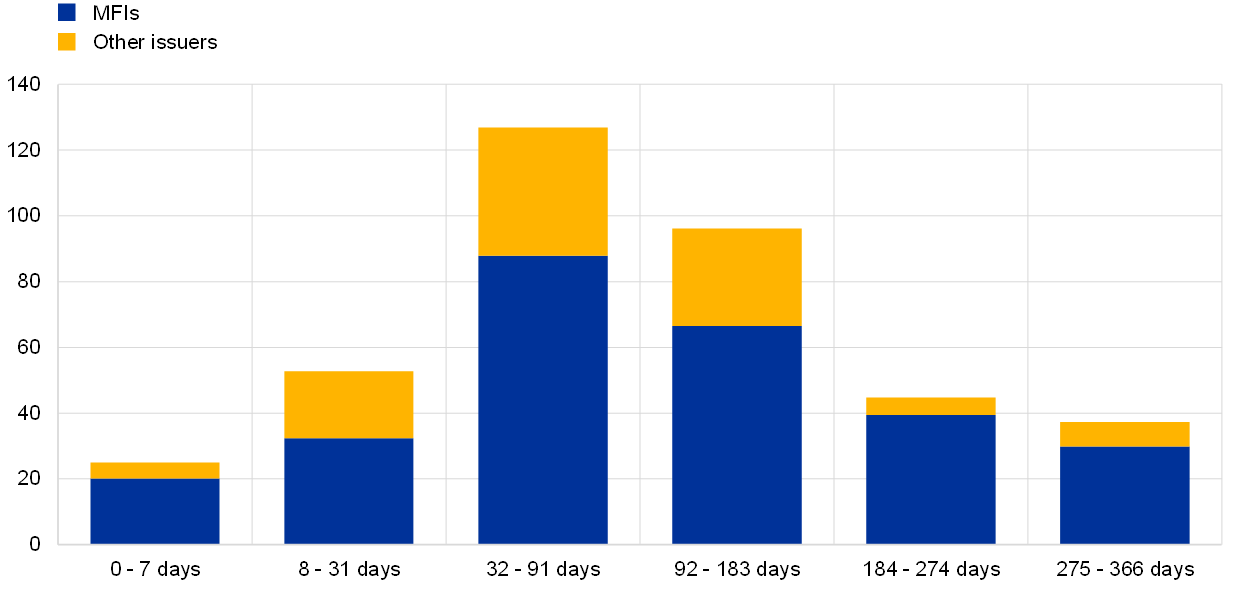

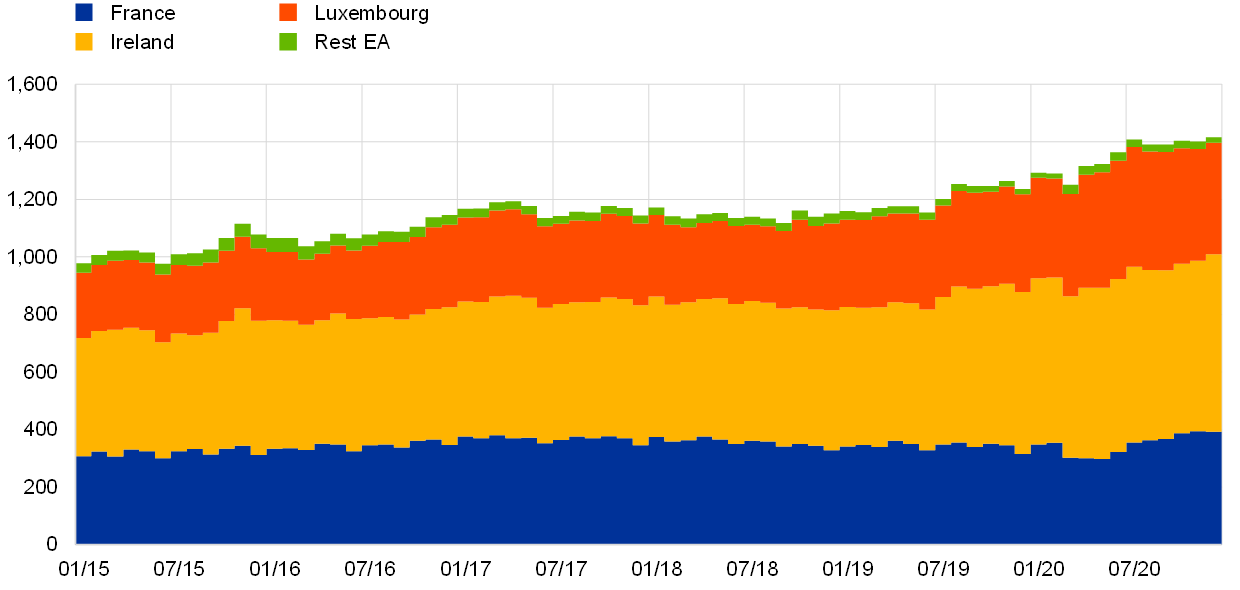

3 The short-term debt securities segment

The STS segment encompasses the issuance of commercial paper and certificates of deposit by various market players (e.g. banks and their underlying clients, corporations, public authorities and financial purpose vehicles) to manage their cash and liquidity positioning. This study analyses the STS mostly issued by euro area banks, and which have a maturity of up to 12 months. While STS with maturities of up to two years and sovereign treasury bills are also considered to be short-term tradable securities, they are not covered by the STS segment of the present money market study.

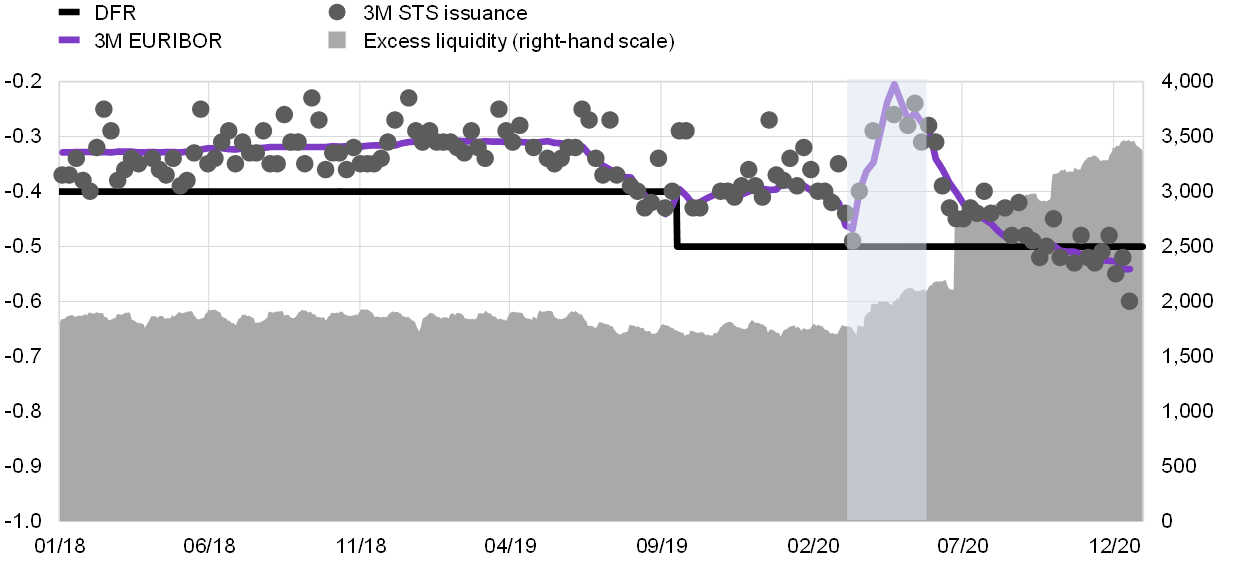

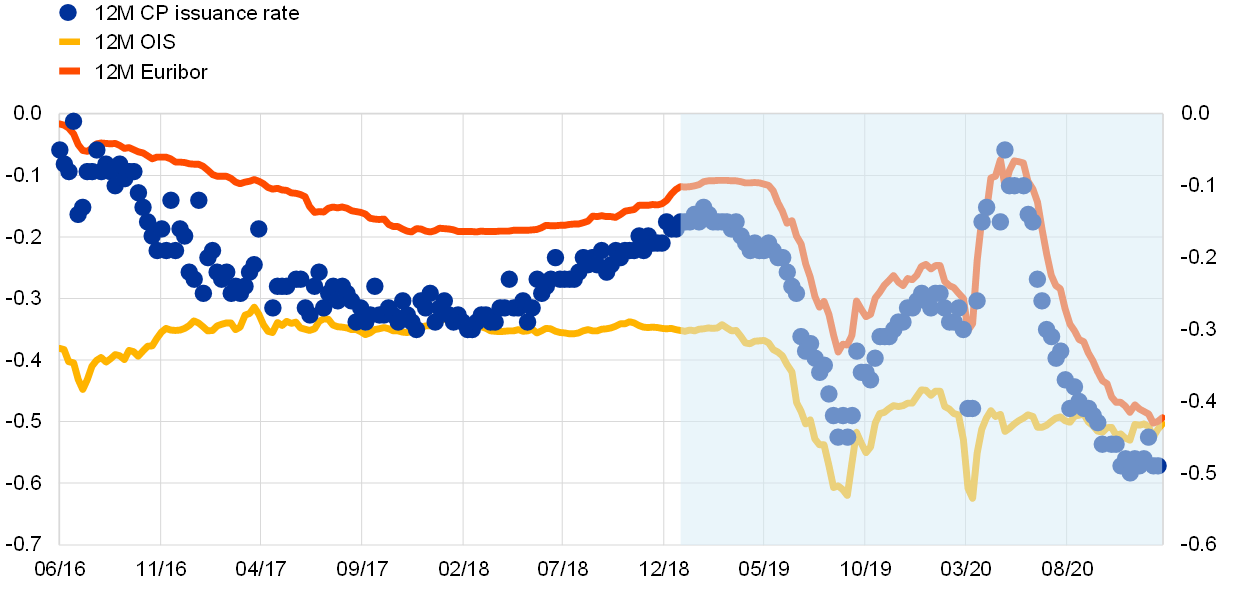

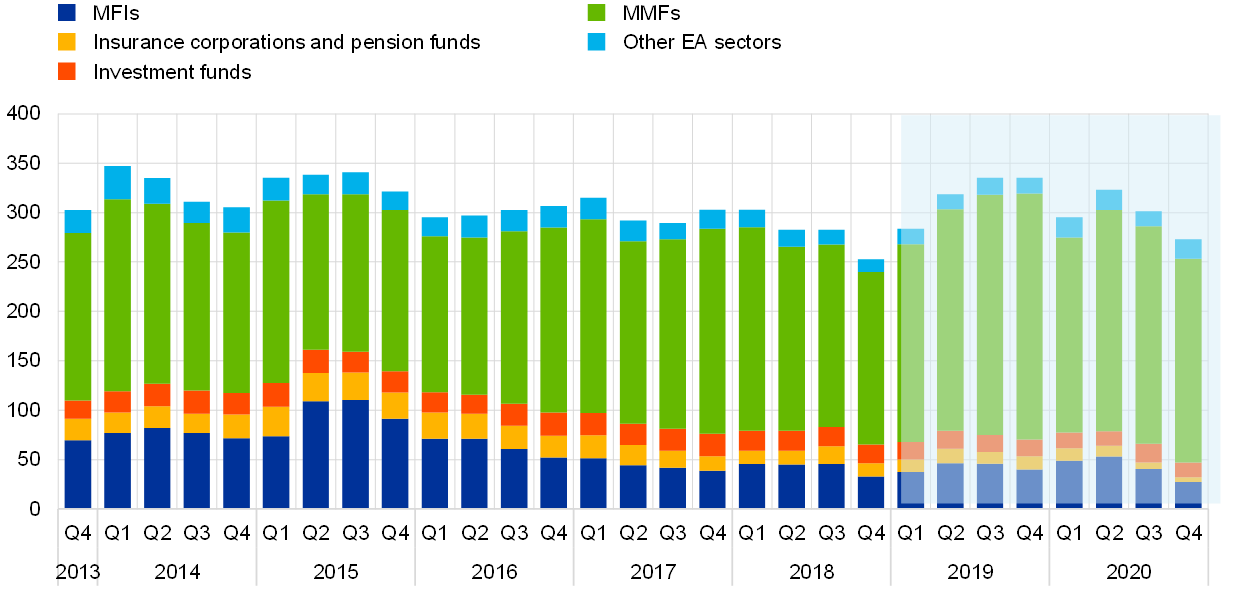

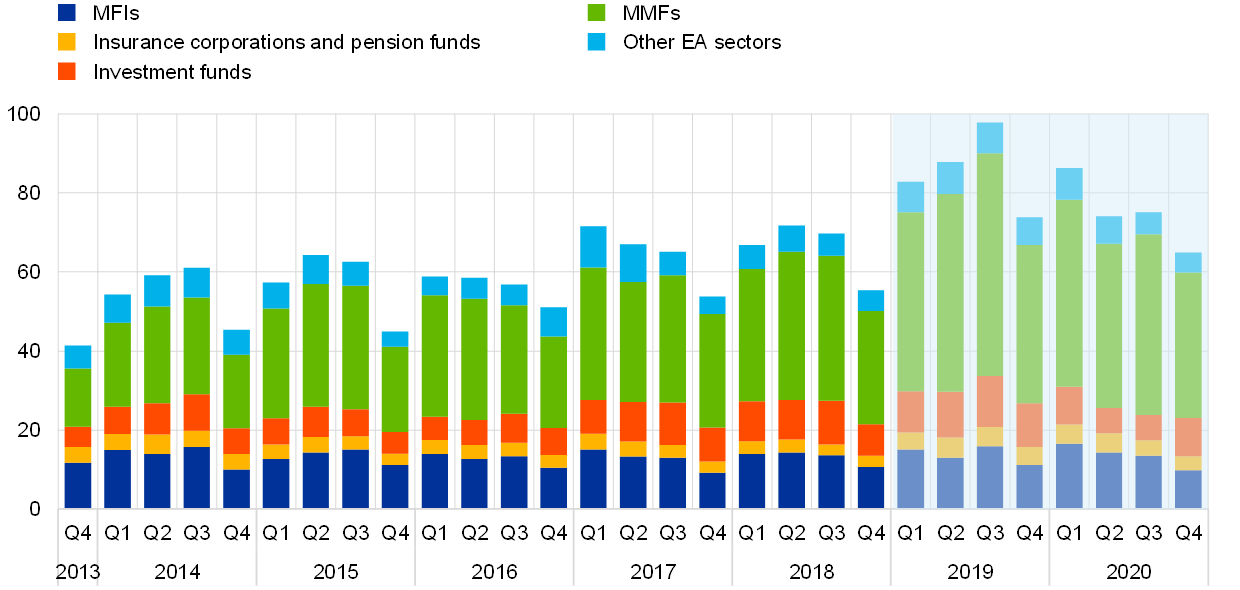

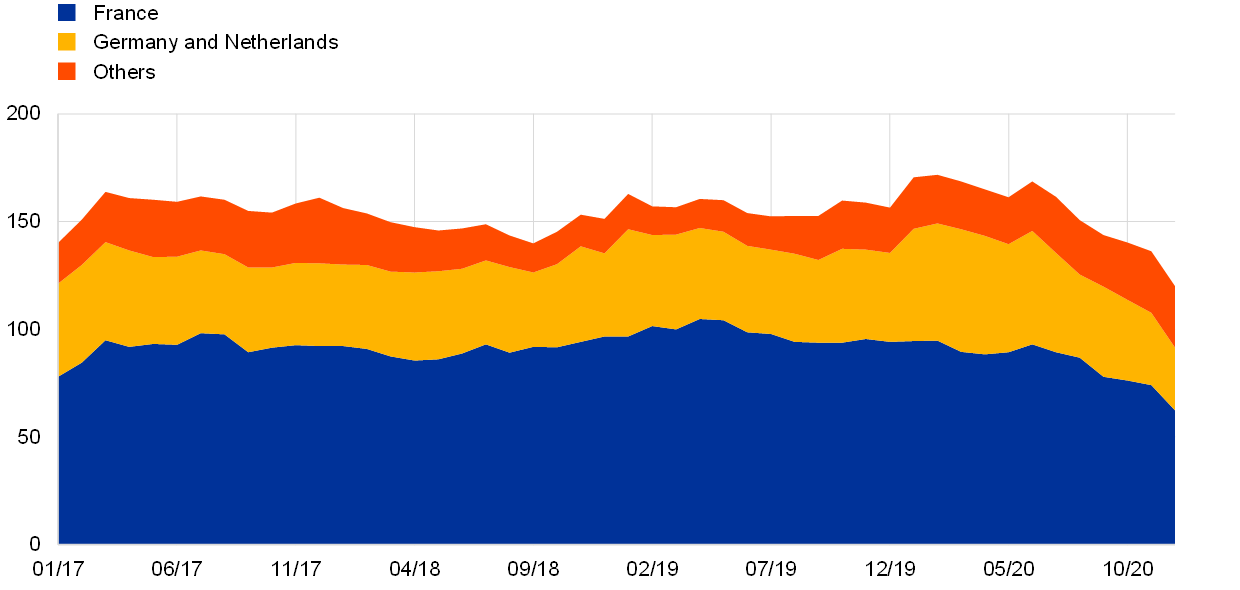

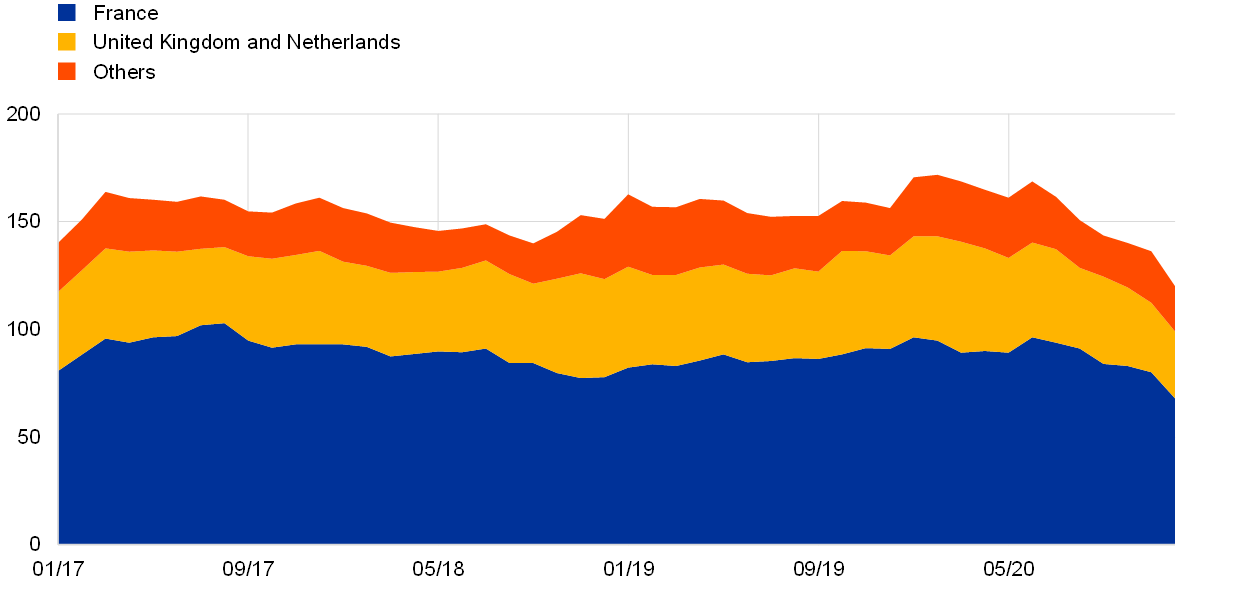

Until the COVID‑19 crisis, the euro-denominated segment for STS had remained relatively stable, in terms of both yields and volumes. Most issuances are from banks located in France, Germany and the Netherlands, while the MMFs sector remains the main investor in STS.

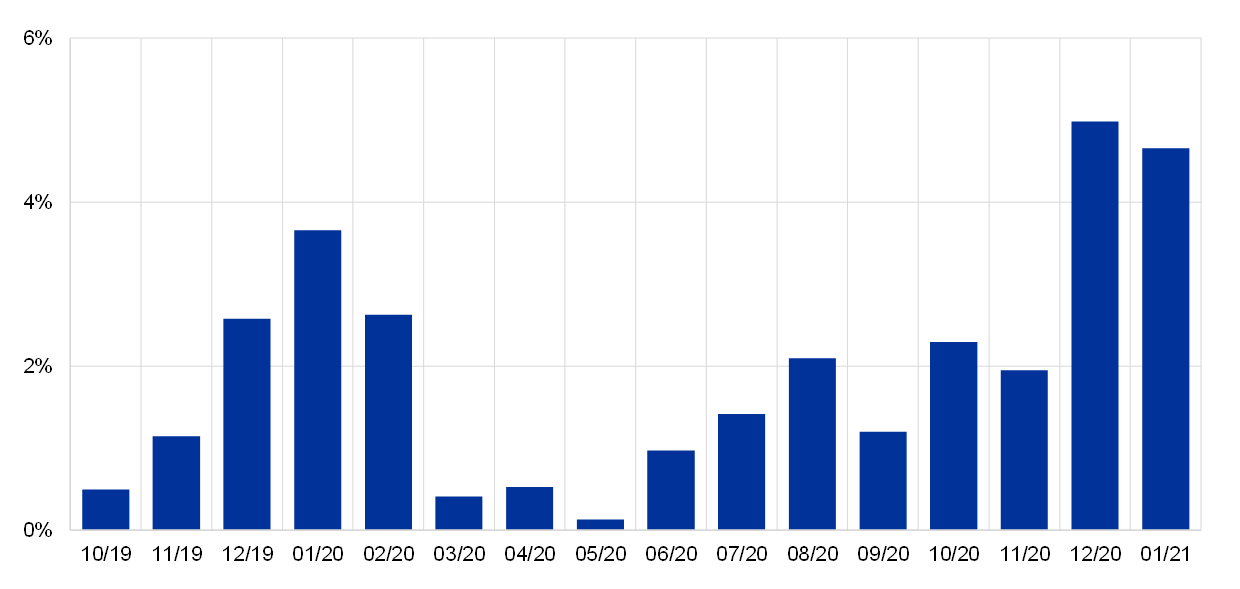

When the COVID‑19 crisis erupted liquidity in the STS segment temporarily dried up as banks and investors focused on reducing risk and preserving liquidity. MMFs struggled to dispose of some of their STS holdings to meet outflows from their unit holders. Throughout the crisis, outflows have accelerated due to the fears of final investors that MMFs will have to face redemption gates in the imminent future. Under these circumstances, yields temporarily increased as investors demanded a significant liquidity risk premium to purchase new STS. European MMFs were able to meet all the outflow demands of their unit holders at the peak of the crisis, either by retaining cash from maturing securities or by selling their STS holdings in stressed secondary markets. In the second quarter of 2020, prices for STS of up to six months increased from slightly below DFR to well above it, peaking at ‑0.17% in April 2020. Moreover, a shortening was observed of the maturities of STS issued by banks, while public entities and corporate issuers moved issuances to longer tenors.

Since May 2020 confidence in the STS segment has gradually been restored and issuance has restarted for longer-dated tenors. Eurosystem interventions aimed at purchasing commercial paper issued by corporates provided liquidity to STS eligible under the PEPP, easing the cash outflows experienced by MMFs. Additionally, new corporates and non-bank financial intermediaries registered for the STEP programme to become eligible for Eurosystem purchases. In the second half of 2020, banks’ issuances in STS declined as the Eurosystem’s TLTROs became their main source of funding. By contrast, public entities and NFCs increased their issuance of STS relative to pre-pandemic levels, reflecting the greater funding required to navigate the COVID‑19 crisis. Prices for both shorter and longer tenors progressively returned to pre-pandemic levels, stabilising slightly below the DFR.

3.1 Volumes – outstanding amounts

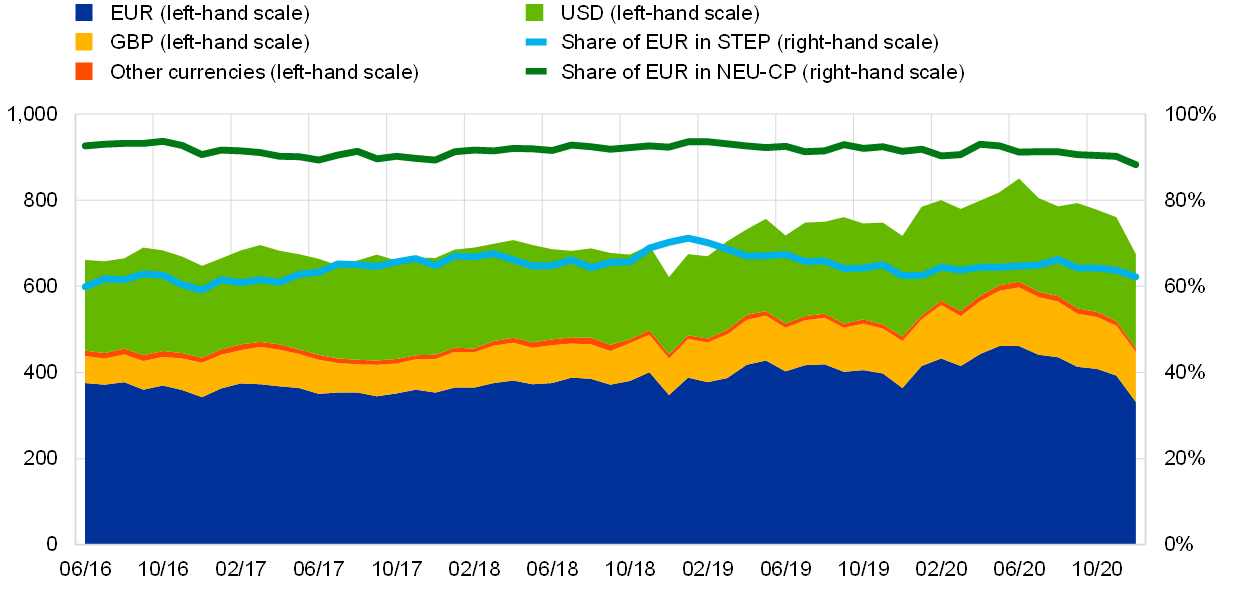

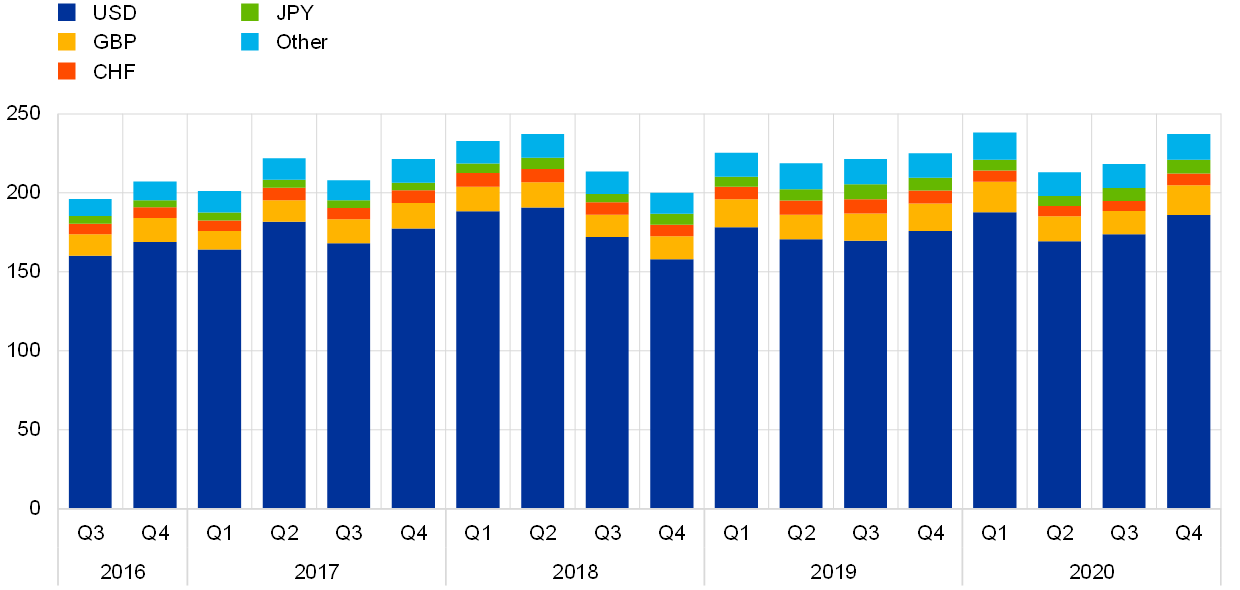

2019‑20 trends

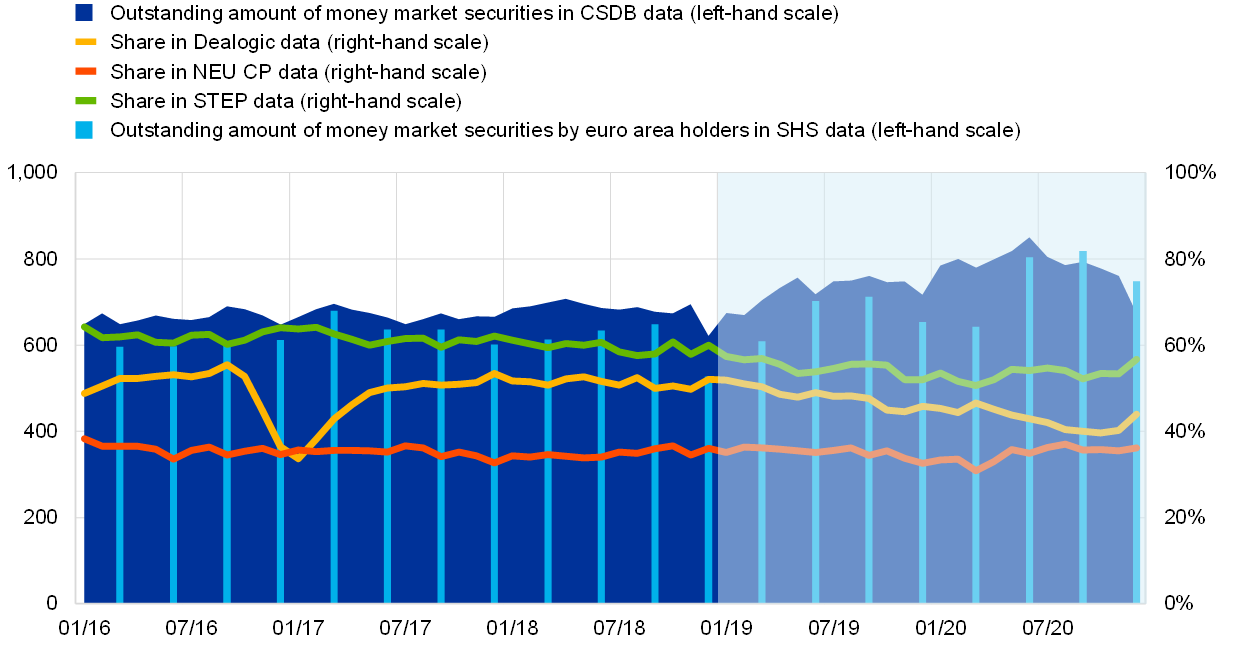

The size of the European STS segment[14] at the end of 2020 – including all currencies and all issuers – was €675 billion (see Chart 3.1). While the term “STS segment” generally refers to securities with a maturity of up to two years, the analysis covered in this chapter only considers maturities of up to one year.

Chart 3.1

European STS outstanding amount, all issuers

(left-hand side: EUR billions; right-hand side: percentages)

Sources: CSDB, SHS.

Notes: The total outstanding amount of money market securities is based on the CSDB, which contains data on “commercial paper”, “certificates of deposit” and “other money market instruments”, according to CSDB nomenclature, with a maturity of up to 12 months for all currencies. The lines represent the share of outstanding amount for the selected databases relative to the total amount outstanding in the CSDB. Dealogic data include commercial paper and certificates of deposit issued by euro area issuers for all currencies. NEU CP data include securities from euro area issuers for all currencies. STEP data include all STEP-labelled securities for all issuer locations and all currencies. The chart shows the outstanding amounts on the last day of each month.

STS issued by euro area banks represented €176 billion at the end of 2020 (see Chart 3.2). This makes the STS segment an important source of funding for banks.

Chart 3.2

Outstanding amount borrowed by euro area banks

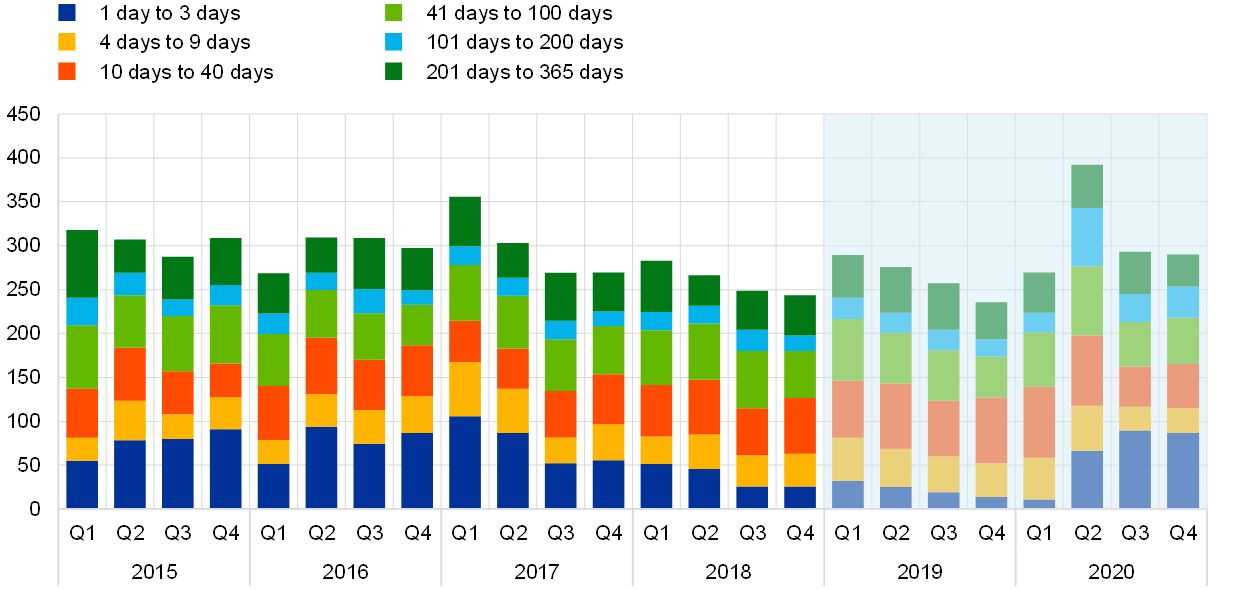

(EUR billions)