Real estate markets in an environment of high financing costs

Real estate markets in an environment of high financing costs

Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2023.

Tighter financing conditions have reduced the affordability of and demand for real estate assets, putting downward pressure on prices. They have also increased the debt service costs faced by existing borrowers, with more-indebted borrowers in countries with widespread variable-rate lending being the most affected. Robust labour markets have thus far supported household balance sheets, thereby mitigating credit risk in banks’ relatively large residential real estate exposures. Commercial real estate firms, by contrast, have faced more severe challenges in a context of rising financing costs and declining profitability. While banks have smaller exposures to commercial real estate markets, losses in this segment could act as an amplifying factor in the event of a wider shock.

1 Introduction

Imbalances in real estate markets can cause financial crises, as has been seen several times in the past. The 2008 global financial crisis is the most prominent example of the financial and macroeconomic instability caused by credit-fuelled real estate boom-bust cycles. The importance of real estate markets for financial stability stems from the strong link between the real estate sector and significant parts of the economy, including the banking sector.[1]

Real estate markets in the euro area have received closer attention due to their dynamism in recent years.[2] This dynamism has been the result of both cyclical forces and structural changes such as the shift to e-commerce and hybrid working, leading to the accumulation of significant vulnerabilities in euro area real estate markets.[3] Residential real estate (RRE) and commercial real estate (CRE) entered a downturn in mid-2022, in the case of RRE after a decade-long boom (Chart B.1, panel a) and in the case of CRE after a brief post-pandemic recovery (Chart B.1, panel b). These developments call for an assessment of the conditions and channels which could lead to risk materialisation and broader financial instability in an environment of high interest rates.

Chart B.1

As RRE and CRE markets enter a downturn, losses could materialise in the financial system

a) Consumer sentiment in housing markets | b) Investor views on the CRE cycle | c) Bank exposures to RRE and CRE |

|---|---|---|

(Q1 1999-Q3 2023 intention to buy a house, Q4 2002-Q2 2023 housing market prospects; net percentages ) | (Q2 2015-Q2 2023, percentages of investors surveyed ) | (Q4 2022, percentages of total loans and advances) |

|  |  |

Sources: Panel a: ECB (BLS, European Commission). Panel b: RICS, ECB and ECB calculations. Panel c: ECB (supervisory data).

Notes: Panel a: the ECB’s bank lending survey (BLS) shows what net percentage of banks report that housing market prospects contribute to an increase (+) or a decrease (-) in mortgage loan demand. A negative reading therefore implies many banks reporting that the current housing market prospects are putting a drag on loan demand. Hence, an indirect connection between the BLS results and housing market prospects can be inferred.

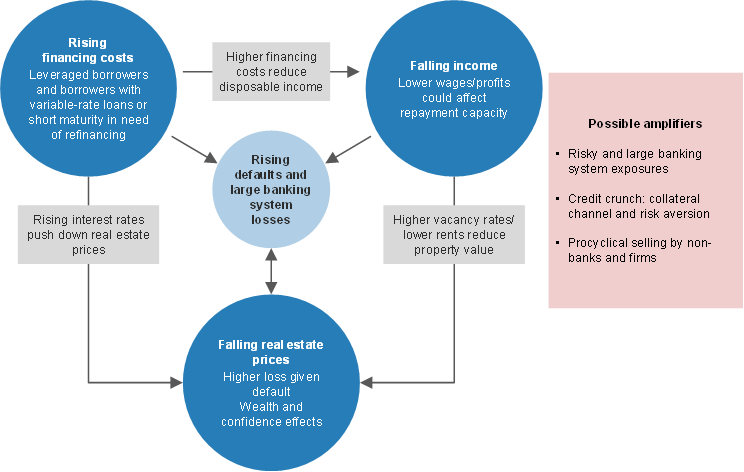

Real estate price corrections and borrowers’ impaired debt servicing capacity related to high financing costs could lead to bank losses (Figure B.1). Rising interest rates reduce the affordability of and demand for real estate assets. This pushes down real estate prices and exposes banks to losses where real estate assets are used as collateral – by increasing banks’ losses given default (LGDs).[4] At the same time, rising interest rates push up financing costs via higher debt service costs, and this increases the probability of default (PD), particularly where borrowers face income challenges. Bank losses can be significant and widespread when LGDs and PDs increase in tandem, which has systemic implications. This special feature discusses first how price and collateral channels affect LGDs and then how the cost of borrowing and income impact PDs.

Figure B.1

A combination of rising financing costs, falling real estate prices and negative income shocks for households and real estate firms could lead to banking sector losses

While the current environment places greater pressure on banks’ CRE exposures, these exposures are less systemically important than their RRE portfolios. Both CRE and RRE markets are in a downturn and existing borrowers are faced with higher debt service costs amid high interest rates. While mortgage borrowers’ debt servicing capacity is currently supported by robust labour markets, CRE borrowers face declining profitability. This exposes CRE portfolios to a higher likelihood of facing debt servicing challenges. Banks’ RRE exposures are large, with residential mortgages accounting in aggregate for almost 30% of euro area banks’ total loans. By contrast, banks have around 10% of loans exposed to CRE (Chart B.1, panel c).[5],[6] While the relatively limited size of bank CRE portfolios implies that they are unlikely on their own to lead to a systemic crisis, they could play a significant amplifying role in the event of broader market stress.

2 Sizing up the potential for losses: price and collateral channels

Higher financing costs after a long RRE boom are putting cyclical downward pressure on overvalued house prices. A standard asset-pricing model can be used to link equilibrium real estate prices to the discounted value of the cash flow that a property could provide if rented out. As the discount factor enters the denominator of the price equation, the relationship between property prices and interest rates is negative.[7] Following the global financial crisis, accommodative monetary policy and the easing of mortgage conditions by banks, together with a shift in households’ preference to hold real estate assets during the pandemic, seem to have been the most important drivers of protracted and robust increases in house prices (Chart B.2, panel a). These factors all contributed to increasingly stretched house price valuations in the euro area.[8] By contrast, positive contributions from monetary policy and banks’ financing conditions have dissipated since the start of 2022. Tighter financing conditions have resulted in higher debt service costs for borrowers and tighter credit standards on mortgages,[9] making it more expensive and more difficult for prospective borrowers to obtain financing, which in turn has put downward pressure on house prices. As a reflection of this, the extent of downside risks to RRE prices as measured by the ECB’s RRE price-at-risk model has increased abruptly, although it remains at much less severe levels than those seen during the global financial crisis (Chart B.2, panel b).

Unlike cyclical developments, structural and supply-related factors continue to support prices in housing markets. In recent years, housing completions in the euro area have remained below their average level since the start of monetary union,[10] indicating a possible accumulated structural gap between housing demand and housing supply.[11] In addition, rising construction costs due to supply shortages and high input costs are exerting upward pressure on house prices.[12] These factors are currently mitigating downside risks to house prices. Over the medium term, however, exposure to both physical and transition climate risk could lead to lower valuations for properties in certain locations and housing units with lower energy efficiency.[13]

Chart B.2

Cyclical factors are putting downward pressure on house prices, while structural and supply-related factors are continuing to support prices, at least in the near term

a) Decomposition of real RRE price growth | b) Tail risk to euro area house price growth |

|---|---|

(Q1 2014-Q4 2022; contributions as a share of identified shocks, percentages) | (Q1 2000-Q3 2023; 5th percentile of predicted real year-on-year house price growth rate distribution, percentages) |

|  |

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: results from a vector autoregression model including real RRE prices, real lending for house purchases, the nominal lending rate on new loans for house purchases, the nominal shadow rate, real residential investments, and real disposable income. We use quarterly series for the euro area aggregate covering the period from Q1 2000 to Q4 2022. The fundamental drivers (structural shocks) are identified using a combination of zero and sign restrictions, with restrictions being based on relevant empirical literature.* “Post sovereign debt crisis” refers to Q1 2014-Q4 2019; “Early pandemic” refers to Q1-Q4 2020; “Late pandemic” refers to Q1 2021-Q1 2022; “Recent” refers to Q1 2022-Q1 2023. Panel b: results from an RRE price-at-risk model based on a panel quantile regression on a sample of 19 euro area countries. The RRE price-at-risk is defined as the 5th percentile of the predicted RRE price growth; this provides an indication of how severe an RRE price decline could be in extreme cases. Explanatory variables: lag of real house price growth, overvaluation (average of deviation of house price/income ratio from long-term average and econometric model), systemic risk indicator, consumer confidence indicator, financial market conditions indicator capturing stock price growth and volatility, government bond spread, slope of yield curve, euro area non-financial corporate bond spread, and an interaction between overvaluation and a financial conditions index.

*) Jarociński, M. and Smets, F., “House Prices and the Stance of Monetary Policy”, Review, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2008; Calza, A., Monacelli, T. and Stracca, L., “Housing Finance and Monetary Policy”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 11, 2013; and Nocera, A. and Roma, M., “House prices and monetary policy in the euro area: evidence from structural VARs”, Working Paper Series, No 2073, ECB, 2017.

The post-pandemic recovery in CRE markets reversed sharply as interest rates started to increase (Chart B.1, panel b). Credit registry data for the euro area indicate that average rates on new loans for the purchase of CRE assets have increased by 2.6 percentage points since interest rates started moving upward.[14] Rising interest rates and overall uncertainty, combined with the inherent illiquidity of CRE markets, resulted in a sharp 47% drop in the number of transactions conducted in euro area CRE markets over the first half of 2023 compared with the first half of 2022. This has inhibited price discovery, which is hampering the assessment of actual market dynamics. The performance of real estate firms in equity markets, which are more liquid, suggests substantial price declines, with the euro area’s largest listed landlords trading at a discount of over 30% to net asset value (NAV), their largest discount since 2008 (Chart B.3, panel a).[15]

Chart B.3

The adverse effects of rising interest rates on CRE valuations are compounded by illiquidity and structural changes resulting in lower demand for certain types of assets

a) Median price-to-NAV of large euro area landlords | b) Rent growth expectations in prime and non-prime office and retail markets |

|---|---|

(2004-22, market value as a percentage of book value) | (Q1 2014-Q2 2023; 12-month rent growth expectations, percentages) |

|  |

Sources: Panel a: LSEG and ECB calculations. Panel b: RICS and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: calculations are based on a sample of listed euro area CRE companies. The number of firms in the sample increases over time, with 100-150 firms in 2004 rising to 260 firms in 2023. Panel b: based on survey data.

Structural challenges and climate change concerns are aggravating downside risks in certain segments of the CRE market. Cash flow prospects, as illustrated by expected rental growth, in both the office and retail sectors remain substantially below pre-pandemic levels (Chart B.3, panel b). This likely reflects the fact that behavioural changes following the pandemic (i.e. hybrid working and increased use of e-commerce) have permanently reduced demand in these segments. Moreover, the difference between prime and non-prime assets in terms of rental growth expectations has also widened in recent quarters, with the outlook for the non-prime market being particularly negative (Chart B.3, panel b). For the office segment, this partly reflects demand for higher-quality space as firms downsize their total office usage. However, climate change concerns have also been a major driver of this shift. Market participants are indicating that demand is increasingly concentrated in the market for high-quality buildings with good energy ratings. In addition, lower-quality buildings face rising retrofitting costs, which exacerbate downward pressure on prices. Thus, while the price outlook for the market as a whole is negative, outcomes may be particularly severe in non-prime markets.

3 Debt servicing capacity and scope for borrower distress

Debt servicing capacity – a central factor driving PDs – is determined by a borrower’s leverage, income prospects and exposure to higher interest rates. Borrowers with variable-rate loans are typically most exposed to rising interest rates as their loans reprice in line with market rates. Among fixed-rate borrowers, short maturity lending that needs to be rolled over and loans with short interest rate fixation periods also create exposure to higher rates. Risks are amplified when borrowers are highly leveraged, which can be measured by metrics such as the loan-to-income (LTI) ratio. Crucially, financial stability may be at risk if and where borrowers’ incomes are not sufficient to meet these higher financing costs, pushing up loan PDs at a time when LGDs are also rising.

Firms and households in some euro area countries are particularly exposed to rising interest rates, given their extensive use of variable-rate lending. While the interest rates on new loans have direct implications for real estate prices, it is the cost of servicing the existing stock of loans that affects debt servicing capacity. The use of fixed- and variable-rate lending differs significantly across euro area countries. Fixed-rate lending makes up the bulk of outstanding bank loans in Germany, France and the Netherlands while variable-rate lending dominates in Finland and the Baltic states (Chart B.4, panels a and b). This, combined with a varying degree of reliance on short-term loans which need to be rolled over, creates substantial cross-country differences in exposure to rising interest rates. According to credit registry data, the average financing costs on the stock of loans borrowed by real estate firms in Germany and the Netherlands have increased by about 0.75 percentage points since 2019 and in Finland by as much as 2.75 percentage points (Chart B.4, panel a).[16] This implies that in some euro area countries borrowers tend to bear the burden of rising interest rates, while for lenders interest income increases with financing costs when interest rates rise. Of course, from a wider financial stability perspective, the widespread use of fixed-rate lending may entail interest rate risk for the banks, when the interest margin turns negative due to rising interest rates on liabilities.

Chart B.4

Highly leveraged borrowers with variable-rate lending are most exposed to rising interest rates

a) Real estate firms’ exposure to rising interest rates and increases in financing costs since 2019 | b) Households’ exposure to rising interest rates | c) Leverage among real estate firms and households |

|---|---|---|

(left-hand scale: June 2023, percentages of total bank loans to real estate firms by exposure to rising rates; | (July 2023; percentages of total bank mortgage loans per interest rate fixation period at origination) | (left-hand scale: multiples; 2005-21 debt: EBITDA < €100m assets, 2004-22 debt: EBITDA > €100m assets; |

|  |  |

Sources: Panel a: ECB (AnaCredit) and ECB calculations. Panel b: ECB and ECB calculations. Panel c: LSEG (firms > €100m assets), BvD Electronic Publishing GmbH – a Moody’s Analytics company (firms < €100m assets), Eurostat and ECB (QSA, household debt-to-income) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: a loan is defined as exposed to rollover risk if it matures within the next two years. Panel b: approximation of information for mortgage stocks using interest rate fixation periods at origination of cumulative mortgage flows since data availability starts or for the period equalling the average mortgage loan maturity when this period is shorter than data availability. Some national authorities have country-specific data on fixation periods of the mortgage stocks, but differences between the national data and the approximation based on flows are not substantial in most cases. Some differences can be seen, however, for Ireland (see Figure 1 in Byrne et al.*), Italy, Slovenia or Luxembourg, for example. Greece excluded due to data quality issues.

*) Byrne, D., McCann, F. and Gaffney, E., “The interest rate exposure of mortgaged Irish households”, Financial Stability Notes, Vol. 2023, No 2, Central Bank of Ireland, 2023.

The impact of higher interest rates is amplified by leverage, which among households and larger real estate firms is close to or above pre-GFC levels. The ratio of household debt to income increased between 2020 and 2022 – the late phase of the housing market boom (Chart B.4, panel c).[17] A similar pattern is visible for the debt/earnings ratio of large real estate firms. This metric may deteriorate further as these firms’ earnings decline and CRE prices are revalued downwards. Indeed, the first signs of such a dynamic are already visible for the largest firms’ debt/earnings ratios at the end of the review period. This could pose a challenge for highly leveraged firms that need to roll over existing debt and that face notably higher financing costs or even reduced access to credit. Indeed, between February 2022 and March 2023, Moody’s carried out negative ratings actions on 40% of European real estate firms and cited deteriorating debt/asset ratios – an alternative leverage measure – in 70% of these.[18],[19] Where this dynamic requires firms to collectively deleverage, it could create a negative feedback loop between access to financing and CRE prices.

For households, while rising debt service costs may challenge debt servicing capacity, strong labour markets are mitigating default risk on mortgages. A microsimulation analysis assessing debt servicing capacity indicates that rising interest rates have pushed loan service-to-income (LSTI) ratios on variable-rate loans up by 8.0 percentage points on average since 2021. Half of existing highly leveraged borrowers with long maturity loans at origination could see their LSTI ratios increase by more than 15.0 percentage points, while for 10% of them the increase could exceed 25.7 percentage points (Chart B.5, panel a).[20] In addition to debt service costs, the income of a given borrower is an important determinant of default risk (Chart B.5, panel b), implying that a scenario featuring a substantial weakening of the labour market would be a source of concern from a financial stability perspective.[21],[22]

By contrast, real estate firms are vulnerable to losses in the current environment, with consequences for the resilience of banks’ loan books. Loans to landlords account for around two-thirds of banks’ exposures to real estate firms, while structurally lower demand for CRE assets reduces landlords’ capacity to raise rents. Developers and landlords alike face rising costs from inflationary pressures and capital expenditures associated with higher energy efficiency requirements. Developers are under further pressure from falling sales prices and contracting order books. This implies that profits for real estate firms may in fact fall in the coming years rather than keep pace with rapidly rising financing costs, posing challenges to debt servicing capacity. Indeed, a deterioration in firms’ fixed charge ratios was the most commonly cited factor in Moody’s recent rating downgrades.[23] As for bank loans to real estate firms, the recent rise in financing costs may cause the share of loans extended to loss-making firms to double to as much as 26%. If tighter financing conditions persisted for two years and firms were required to roll over all maturing loans, this number would increase to 30%. Finally, 53% of loans in the sample would be to loss-making firms if firms simultaneously experienced a 20% drop in turnover. In some cases, losses are substantial – for 17% of loans, annual losses exceed 10% of the firm’s total capital (Chart B.5, panel c).[24] These results suggest there are substantial vulnerabilities in this loan book, particularly when considering that it is expected that both higher financing costs and reduced profitability will persist for a number of years. Indeed, business models established on the basis of pre-pandemic profitability and low-for-long interest rates may become unviable over the medium term.

Chart B.5

Higher debt service costs may have credit risk implications for variable-rate loans and for real estate firms with weak profitability

a) Simulated increases in LSTI ratios on variable-rate loans since end-2021 | b) Marginal effects of factors relevant for household probabilities of default | c) Share of total real estate firm loans to loss-making firms under three scenarios |

|---|---|---|

(2012-23, percentage points) | (effects on probability of default) | (June 2023, percentages) |

|  |  |

Sources: Panels a and b: EDW and ECB calculations. Panel c: BvD Electronic Publishing GmbH – a Moody’s Analytics company, ECB (AnaCredit) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panels a and b: only variable-rate loans are shown in countries available in EDW (Ireland, Spain, Italy and Portugal). Panel a: loans originated in 2012-21; loans expiring before 2023 dropped. The chart shows simulated increases in LSTI ratios between 2021 and 2023. LSTI ratios in 2023 are calculated on the basis of the household cost of borrowing (MIR) in August 2023 plus 25 basis points interest rate hike in September. Boxes based on 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles, whiskers on 1st and 99th percentiles. The total is weighted by GDP. Further details on the methodology underlying this analysis can be found in the article entitled “Gauging the sensitivity of loan-service-to-income (LSTI) ratios to increases in interest rates”, Macroprudential Bulletin, Issue 19, ECB, October 2022. Panel b: the chart shows average marginal effects of relevant right-hand-side variables included in the logistic regression of one-year-ahead probabilities of default of mortgage loans. Further details can be found in the article entitled “The analytical toolkit for the assessment of residential real estate vulnerabilities”, Macroprudential Bulletin, Issue 19, ECB, October 2022. Panel c: based on a sample of 115,000 firms for which profitability data are available in the BvD dataset, accounting for approximately 25% of loans in AnaCredit to real estate firms. Firms’ losses categorised by size relative to firm capital. Sample coverage across countries varies, with countries where variable-rate lending is prevalent generally having higher coverage than those which typically use fixed-rate lending. Firm profitability, including the estimated impact of changes in financing costs, is calculated as 2019 net income (excluding the effects of depreciation/amortisation) – (change in borrower average cost of financing) *total debt. This is normalised by firm capital, which includes all equity and reserves. Under a full pass-through scenario, (1) the further 50 basis points of monetary tightening which has occurred since June 2023 is incorporated in all variable-rate loans; (2) all loans expiring within two years are rolled over at the new rates; and (3) all fixed-rate loans with rate resets scheduled in the next two years are updated to the new rates, where new rates are calculated as original interest rate + change in long-term government bond yields since original loan inception. A 20% decline in turnover is uniformly applied to all firms to account for the various profitability headwinds facing the real estate sector discussed in the main text. AnaCredit data are as at June 2023.

4 Conclusions

While mitigating factors are supporting banks’ large mortgage portfolios for now, banks’ smaller CRE exposures appear to be more vulnerable. Despite falling real estate prices and rising financing costs in both RRE and CRE markets, robust labour markets are currently helping to mitigate credit risk in mortgage portfolios. However, any substantial weakening of the labour market would pose significant risks to the RRE portfolios. By contrast, the weak profitability outlook is creating greater downside risks in banks’ CRE portfolios. Aggregate CRE exposures are substantially smaller than for RRE and are unlikely by themselves to be large enough to cause a systemic crisis at the euro area level. Nevertheless, a scenario where real estate firms suffer very large losses would likely coincide with stress in other sectors. In this way, CRE market outcomes have the potential to significantly amplify an adverse scenario, increasing the likelihood of systemically relevant losses being incurred in the banking system. Moreover, a negative outcome of this type would also drive large losses in other parts of the financial system which are significantly exposed to CRE, such as investment funds and insurers.

Macroprudential policy measures might also help to reinforce resilience, especially for RRE. Almost all euro area countries have implemented macroprudential measures to address RRE vulnerabilities, but policy action targeting CRE has been much more contained. Many countries increased macroprudential capital buffers or implemented borrower-based measures in response to increasing RRE vulnerabilities after the pandemic subsided. By mid-2023, 15 of the 20 euro area countries had put borrower-based measures in place, ten had implemented targeted capital-based measures (sectoral systemic risk buffers or measures to increase risk weights), and several had increased broad countercyclical capital buffers (among others) in response to the high level of accumulated RRE vulnerabilities.[25] By contrast, very few measures in euro area countries target CRE vulnerabilities, as the complexity of CRE markets and the high number of diverse players make a policy response more difficult to design.[26] While the range of tools applicable at the level of banks is, in principle, identical to that of the RRE toolkit, measures available to investment funds or insurance corporations are scarce. In addition, data gaps are more substantial than they are for RRE and hinder risk assessment. All in all, a comprehensive policy response for CRE markets would require multiple measures to be implemented to target all exposed actors and avoid leakages and would need to take particular care to avoid procyclicality. Regardless of whether targeted RRE or CRE measures are in place in each country, however, the internal processes of banks and non-banks should ensure that their provisioning practices and capital properly reflect the level of accumulated vulnerabilities.

See the article entitled “Real estate markets, financial stability and macroprudential policy”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 19, ECB, 2022.

See the section entitled “Vulnerable real estate markets are turning”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2023.

Those vulnerabilities relate in particular to real estate price overvaluation and accumulated indebtedness collateralised by real estate, or by real estate firms.

Indirectly, a fall in house prices can also have negative implications for household consumption via wealth effects or confidence and can reduce access to credit for firms that use real estate as collateral (see, for example, Horan, A., Jarmulska, B. and Ryan, E., “Asset prices, collateral and bank lending: the case of Covid-19 and real estate”, Working Paper Series, No 2823, ECB, 2023).

This figure uses exposures collateralised by CRE as a simple proxy for banks’ exposures to CRE. In some cases, this approach will also capture loans with a purpose other than CRE, but which use CRE collateral, and may also miss some CRE-purposed loans which use non-CRE collateral. However, this simple approach allows for a clear comparison with RRE portfolios. For more detail on types of exposure to CRE among euro area banks, see the article entitled “Commercial real estate and financial stability – new insights from the euro area credit register”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 19, ECB, 2022.

We examine RRE and CRE markets separately as they have different characteristics, participants and past dynamics. For example, there is a historical tendency for CRE exposures to be substantially riskier than RRE exposures due to their more volatile asset market and typically riskier lending practices. Indeed, CRE lending typically has higher LGDs and PDs than RRE markets. Market participants also differ, with RRE markets typically consisting of (domestic) households and banks while CRE markets include firms and a range of (international) non-banks (see the article entitled “Real estate markets, financial stability and macroprudential policy”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 19, ECB, 2022). CRE lending is also often characterised by riskier lending practices than RRE, with wider use of non-recourse lending, bullet lending and complex lending structures.

Indeed, there is a vast empirical literature confirming that higher interest rates tend to put downward pressure on house prices, all else being equal (see Dieckelmann, D., Hempell, H.S., Jarmulska, B., Lang, J.H. and Rusnák, M., “House prices and ultra-low interest rates: exploring the non-linear nexus”, Working Paper Series, No 2789, ECB, 2023).

See the section entitled “Vulnerable real estate markets are turning”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2023. Euro area house price overvaluation estimate stood at 18% in Q2 2022 and at 9% in Q2 2023.

See the Euro area bank lending survey Q3 2023, ECB, 2023.

For discussions on the supply of housing in the euro area, see the article entitled “The state of the housing market in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2018, and Frayne, C., Szczypińska, A., Vašíček, B. and Zeugner, S., “Housing Market Developments in the Euro Area: Focus on Housing Affordability”, European Economy Discussion Paper 171, European Commission, 2022.

Demand for housing is determined by many factors, notably including the affordability of housing and the number of households. The total number of households in the European Union rose by 10.3% from 2009 to 2022, increasing demand in the long term. See also Eurostat’s Household composition statistics, accessed on 28 September 2023.

Construction producer prices for new residential buildings increased by 12% in the EU in 2022. See also Eurostat’s Construction producer price and construction cost indices overview, accessed on 28 September 2023.

For the impact of physical risk on house prices, see, for example, Gourevitch, J.D., Kousky, C., Liao, Y., Nolte, C., Pollack, A.B., Porter, J.R. and Weill, J.A, “Unpriced climate risk and the potential consequences of overvaluation in US housing markets”, Nature Climate Change, Vol. 13, pp. 250-257, 2023, and Benetton, M., Emiliozzi, S., Guglielminetti, E., Loberto M. and Mistretta, A., “Do house prices reflect climate change adaptation? Evidence from the city on the water”, Occasional Papers, No 735, Banca d’Italia, 2022; for the impact of transition risk on house prices, see Ferentinos, K., Gibberd, A. and Guin, B., “Climate policy and transition risk in the housing market”, Staff Working Papers, No 918, Bank of England, 2021.

A comparison of average interest rates on real estate purchase-purposed loans to non-financial corporations from June 2022 to June 2023, weighted by exposure size. These dynamics are largely in line with wider data on new lending to non-financial corporations, which suggests they do not yet include a rising CRE-specific risk-aversion component.

Limited ability to raise rents has also reduced the capacity of CRE to act as an inflation hedge in the way it might have done in previous inflationary periods, particularly at the levels of inflation experienced since early 2022. Indeed, this dynamic has been reflected in real estate firms’ equity valuations, which initially responded well to rising inflation and interest rate expectations but – once the extent of inflationary pressures and the potential interest rate response had become clearer – significantly underperformed wider equity markets.

While variable-rate lending dominates structurally in some countries, there has been an overall trend towards fixed-rate mortgage lending over the last two decades. This trend has seen the share of new loans with variable rates in the euro area falling from around 50% to around 15% between 2003-05 and 2020-22, leading to a shift of some of the risk of rising interest rates from households to banks. The shares of variable-rate lending increased again since the end of 2022, reaching 20% in September 2023. This might reflect the preference of borrowers not to lock in higher interest rates for a longer period and their expectation that interest rates will, on average, be lower over the entire life of the loan. However, the volume of credit for house purchase has fallen substantially since the interest rate hikes started (see the section entitled “Vulnerable real estate markets are turning”, Financial Stability Review, May 2023), so new lending amounts to a limited share of the stock of mortgage loans on banks’ balance sheets.

For a discussion on lending standards for new lending, where loan-to-income ratios have been also increasing until 2022, see the article entitled “Evolution of mortgage lending standards at the turn of the housing market cycle”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 22, ECB, 2023.

Rating actions included both changes in outlook and changes in ratings. See “Corporate credit quality will deteriorate with rising rates, falling property values”, Moody’s, 7 February 2023.

For a discussion of collateral and earning constraints in corporate borrowing, see Horan, A., Jarmulska, B. and Ryan, E., “Asset prices, collateral and bank lending: the case of Covid-19 and real estate”, Working Paper Series, No 2823, ECB, 2023, and Lian, C. and Ma, Y., “Anatomy of Corporate Borrowing Constraints”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 136, Issue 1, February 2021, pp. 229-291.

Based on data on securitised mortgage loans for countries where variable-rate lending prevails (Ireland, Spain, Italy and Portugal, available from European DataWarehouse (EDW)). In the microsimulation, highly leveraged borrowers are those with an LTI exceeding seven while “long maturity” means longer than 30 years. Overall, around 30% of loans in the euro area are granted at variable rates (Chart B.4, panel b).

The euro area unemployment rate stood at a historical low of 6.4% in August 2023 and is projected to increase to 6.7% in 2024. For more details, see the ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, September 2023.

Household default risk may also be mitigated in some countries by support measures for household borrowers that are already in place or being designed. Whether or not a borrower defaults will also depend on accumulated savings. Even in the absence of defaults, however, higher debt service ratios caused by higher interest rates could have significant negative macroeconomic implications due to decreased consumption.

See “Real estate – Europe: Corporate credit quality will deteriorate with rising rates, falling property values”, Moody’s, 7 February 2023.

This analysis is based on a sample of 115,000 euro area real estate firms. For further details on the analysis, see the notes to Chart B.5.

See “Vulnerabilities in the residential real estate sectors of the EEA countries”, ESRB, 2022, the ESRB’s overview of national macroprudential measures and the list of macroprudential measures in euro area countries notified to the ECB.

See “Vulnerabilities in the EEA commercial real estate sector”, ESRB, 2023.