Monetary policy in challenging times

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBLondon, 19 November 2009

Introduction [1]

I would first of all start by thanking you for the invitation to speak about the current challenges facing monetary policy.

There are increasing signs that advanced economies have started a gradual recovery. Policy-makers across the globe have responded rapidly and forcefully – and have had an effect. National governments have adopted extraordinary measures to support the financial sector. They have also implemented fiscal programmes to directly stimulate economic activity. Central banks have lowered policy rates close to zero and introduced a number of unconventional tools to provide liquidity support. The fears of a very bad outcome – like the Great Depression that paralysed the world economy in the 1930s – have receded. But the economic outlook is still uncertain.

Today, I’d like to discuss the current economic and financial situation and outlook. In particular I’ll be asking: are the financial markets recovering more quickly than the real economy, bearing in mind that the growth prospects are still overshadowed by risks? If so, it will prove testing not only for monetary policy but also for other policies. I will consider this challenge against the background of a phasing-out of the exceptional policy measures taken by central banks over the last year.

Economic and financial market developments

The outlook for the economy – both in the euro area and at global level – has improved significantly during the last two quarters. A number of countries have returned to positive growth rates. Asian economies have recently performed strongly. In contrast with developments one year ago, most professional forecasters have started to revise their economic projections upwards.

The Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections will be published in two weeks’ time. I will not anticipate the outcome. But as we stated earlier this month, the latest information continues to signal an improvement in economic activity. According to the flash estimate from Eurostat, the euro area economy grew by 0.4% in the third quarter this year, ending a period of five successive quarters with negative growth rates. Available survey evidence indicates that the situation has continued to improve in the fourth quarter.

But the pace of the recovery is likely to be gradual and uneven. Many of the factors supporting growth are of a temporary nature. The impact of the strong fiscal stimulus will progressively fade, and the positive contribution from the inventory cycle will not last. The banking system is still under pressure, and many households and firms are likely to cut down their debt levels before increasing spending and investment again. Unemployment, which reached 9.7% in the euro area in September, is expected to continue rising for some time in many countries, weighing on consumer spending.

Several risk factors may slow the recovery down. One is a further increase in commodity prices, which might take place if emerging markets pick up more quickly than expected. Oil prices have been trading just below 80 US dollars recently, about a doubling of the price level since the beginning of the year. We saw it earlier this decade: oil price increases were expected to be temporary, but instead they rose steadily, reducing the terms of trade of most advanced economies. Another risk factor is the ability of the banking system to support the economy by providing sufficient credit once the demand for investment starts growing again. This will depend on how well the system restructures its balance sheet and recapitalises over the next few months. Another risk is the potential instability in financial markets, in particular with respect to excess volatility in the foreign exchange markets, which is detrimental to export and investment decisions.

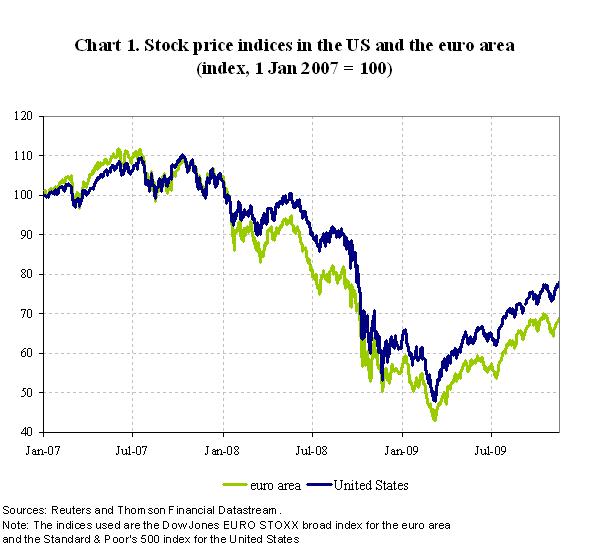

Looking at financial markets, one gets the impression that they are expecting a somewhat stronger recovery. Stock markets in the euro area and the US have increased by about 50% since they bottomed in March, although they are still about 30% to 40% below their 2007 peak levels (see Chart 1). However, price-earnings ratios are back to their historical average, even though we have just been through the worst recession since World War II. In the US the price-earnings ratio for financial corporations is historically high.

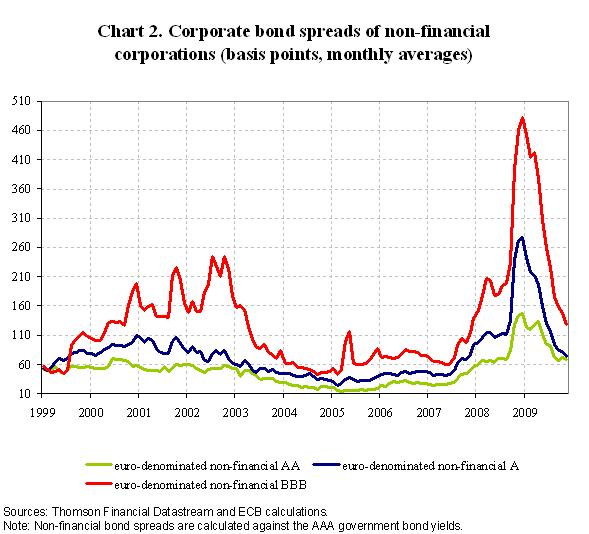

In the corporate bonds market, spreads have declined rapidly in recent months. They are now at levels below those prevailing just before Lehman Brothers’ failure (see chart 2). In the euro area the bond spread for financial corporations with a triple-B rating is currently around 640 basis points. The spread for non-financial corporations with a similar rating is around 120 basis points. Debt issuance by the corporate sector has increased substantially over recent months, suggesting a shift from bank to market-based financing. In the current environment of improving expectations, the recent compression of corporate bond spreads may indicate that conditions in these markets are returning to normal.

Information from long-term government bond yields may embody a more cautious assessment of the growth outlook, as euro area government bond yields declined over the summer. The ten-year government bond yield in the euro area now stands at 3.6%, down from 4.3% in June. But the large-scale issuance of long-term government bonds was met by strong demand from the banking sector and institutional investors. Altogether, recent financial market developments seem to reflect an increase in risk appetite in an environment of low interest rates and improved liquidity in financial markets.

Overall, the assessment underlying financial market conditions appears somewhat more optimistic than the consensus forecast for economic recovery. To some extent this is normal, as financial variables tend to anticipate future economic developments. Yet, the current low levels of interest rates and the progressive return of risk appetite may push investors to take speculative positions that would be consistent with a more optimistic scenario than the baseline.

An interesting question is whether the uncertain prospects for the real economy might be diverging from those for the financial markets, which appear somewhat more optimistic. If this divergence persisted, monetary policy would face a challenge. The underlying stance would appear to be looser, in relative terms, when assessed against the conditions prevailing in financial markets then when compared to real economic developments. This hypothesis seems to be confirmed by the contrasting trends within the banking sector: credit flow to the real economy remains subdued while trading activity has recovered strongly. Monetary policy might thus be insufficiently effective in stimulating economic recovery but too effective with respect to risks of asset price bubbles in the financial sector.

The challenge for monetary policy

How does monetary policy address this potential divergence, in particular in the euro area?

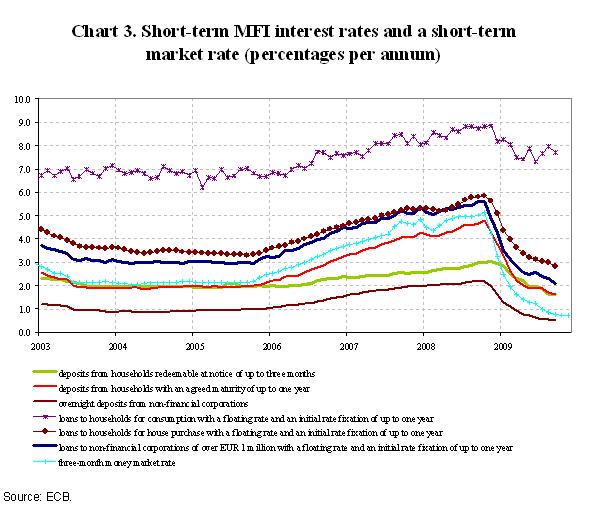

We need to start by looking closely at the data. Take the pass-through of policy rates to lending rates practised by banks to the end users. Evidence shows that lending rates have declined substantially since last autumn, both for households and firms. This has been the result of the cuts in policy rates and the decline in money market spreads, which are now lower than they were just before the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. At the three-month horizon, the spread has declined to about 30 basis points in the euro area. The floating rate on loans to households for house purchase has roughly halved since October last year, and was 2.8% in September (see Chart 3). Overall, the degree of pass-through has been broadly in line with past regularities. But surveys of both firms and banks indicate that financing costs related to non-interest terms and conditions – such as charges and fees or collateral requirements – have been tightened.

Credit aggregates have slowed down significantly over recent months. In September lending to the private sector was 0.3% lower than a year earlier. This was the first negative number since the start of monetary union. In analysing these credit aggregates, we have to keep in mind the interaction between supply and demand. It is always difficult to disentangle two sides. There are several reasons for expecting loan demand to be weak now. As production has declined considerably over the past year, firms may have delayed or cancelled investment projects, and thus reduced their demand for new loans. Similarly, households may think twice about major purchases as job prospects have become more uncertain.

Compared with past downturns, the recent developments in credit flows seem to be in line with historical regularities. In the past, the pick-up in loans to non-financial corporations has lagged the turning points in economic activity by about three quarters. This means that we should expect lending to non-financial corporations to remain relatively subdued for some time. The annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations was -0.1% in September. Lending to households, which tends to move more in line with the turning points in economic activity, was 0.3% lower in September than a year earlier. The monthly loan flows to households have however been positive and increasing since May this year.

Overall, the significant slowdown in lending experienced so far can to a large extent be attributed to weak demand, as surveys both of banks and firms have shown. One example is the recent survey on small and medium sized enterprises’ (SMEs) access to finance, conducted in co-operation between the ECB and the European Commission. According to the survey, three out of five SMEs that had applied for a bank loan in the first half of 2009 received the requested amount in full. Around one in five received the requested amount in part. Only about one in ten had the loan application rejected. However, some supply-side constraints seem to have played a role. Banks have tightened credit standards substantially over the past year. The quarterly survey of banks indicates that the number of banks tightening credit standards has declined, but remains positive. Banks have reported that their liquidity position has helped to ease credit constraints very recently.

While private-sector demand for credit has slowed down, public-sector demand has accelerated. The European Commission projects that the euro area government deficit will increase from 2.0% of GDP in 2008 to 6.4% in 2009 and 6.9% in 2010. The increasing deficit has been met by a strong supply of credit from the banking system. Euro area banks have been buying considerable amounts of government bonds over the past few quarters. This has taken place against a steepening of the yield curve. In the third quarter of 2009 the difference between the yield on longer-term euro area government bonds and the three-month inter-bank interest rate was on average 308 basis points. This is the largest gap since 1980. It suggests that the funding costs for banks have become favourable relative to the yield on longer-term investment such as government bonds.

Overall, the recent purchases of government bonds by euro area banks have not been out of line with what we would expect, given the current circumstances. Historically, bank purchases of government debt securities have shown a strong correlation with the steepness of the yield curve. Banks regard the purchase of government bonds as an attractive strategy, for when making such purchases they park liquidity while demand for loans remains subdued and at the same time they make their portfolios less risky. Beyond the influence our policy has had on the yield curve, the available evidence does not indicate that our liquidity support has led to excessive purchases of government bonds by banks.

To sum up, the divergence between slow credit flow and buoyant trading by the banking system seems to be in line with historical experience under comparable conditions.

The current low level of interest rates is consistent with the analyses conducted under the economic and monetary pillars of the ECB’s strategy, which point to the absence of inflationary pressures. The question is: how long can low levels of interest rates be maintained without creating distortions in the efficient allocation of funds by the financial sector, and possibly endangering price stability? This is at the heart of the exit strategy. Before turning to it, let me make a few remarks about the divergent behaviour within the financial sector, especially in banks.

The challenge for other policies

As I just mentioned, it is no surprise to see a slowdown in credit flows at the same time as a pick-up in trading. To some extent this divergence is desirable because a sound financial system is the key to a sustainable recovery. Still, it might create undesirable volatility in financial markets. To put it in other words, if the abundant liquidity provided by the central banks does not find its way through to the real economy because of weak credit demand, and instead remains within financial channels, we could experience short-term dynamics in the capital markets which may hold back economic growth itself.

Some have downplayed this risk, saying that we are not experiencing the same feedback loops operating through the credit cycle that led to the pre-crisis bubble. [2] According to this view, even if financial markets were to experience some bubbles, they would not be so dangerous as they are not linked to the real economy through the credit channel. They can burst with little risk and few repercussions.

I would be a bit more cautious. Let me remind that the prevailing paradigm before the crisis was that the best way to deal with bubbles should have been to let them burst and thereafter engineer an expansionary monetary policy to counter the negative effects. It might be risky to now move to a new paradigm, potentially as mistaken as the previous one, that only asset price bubbles linked to credit flows are dangerous. Bubbles which feed asset prices, including commodity prices, if protracted, can feed expectations and weaken confidence when they burst, even if they are not associated with a credit boom. In addition, we should not forget that the effects of a bubble burst are the more damaging the more fragile is the state of the economy. We clearly need to study this more closely before we can be relaxed about it.

As the economy stabilises and picks up again over time, and the demand for investment rebounds, the key question will be: can the banking system meet a higher demand for credit? In other words, when the drag on the demand for credit eases, will the supply follow, or will there still be constraints on the flow of credit to the real economy? The answer to this question is the key to the recovery. But it’s not a question that monetary policy can answer.

The banking sector has been restructuring in response to the financial crisis. No doubt about it. This has included a retrenchment from excessive risk-taking as well as capital enhancement and cost-cutting. These measures have helped to absorb the shocks which have occurred since mid-2007, including the sizeable mark-to-market write-downs on impaired assets and, more recently, the losses triggered by the decline in loan credit quality. Loan loss provisions surged and were about a third higher than net interest income earned by euro area large and complex banking groups in the second quarter of 2009. This was the highest level seen in the past five years. The increase in revenues from the core banking business and the considerable cost-cutting have nevertheless boosted profitability this year. Income from trading has recovered strongly in this period, also improving banks’ performance. The restored profitability has recently enabled some European banks to start repaying the capital injections provided by governments, suggesting greater robustness in the system.

However, the trend worsening of non-performing loans should not be considered over yet –it might turn out to be worse than projected. Banks shouldn’t assume that it’s time to go back to previous practices, using their profits primarily to remunerate staff and reward shareholders. They need first of all to give priority to further improving their capital position, as a buffer against worst-case scenarios. Supervisory authorities should keep an eye on banks for this reason.

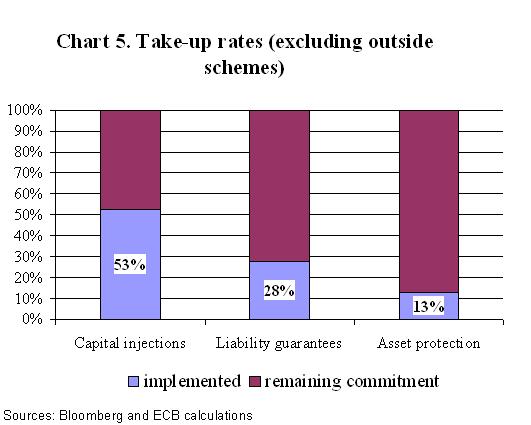

Banks need also to plan for more stable and sustainable long-term sources of financing. It’s interesting to note that non-financial corporations have successfully made large bond issues, while monetary financial institutions have been much more timid, compared with their pre-crisis levels (see Chart 4). Since mid-2008, the annual growth rate of debt securities issued by monetary financial institutions roughly halved to around 4% in September. By contrast, the growth rate of debt securities issued by non-financial corporations increased over the same period from around 3% to 15%. The support mechanisms provided by governments have not been fully utilised, in particular with respect to guarantees (see Chart 5).

In any case, the situation remains imbalanced. Some banks are still very reliant on unlimited central bank financing. These cases have to be addressed rapidly by the responsible national authorities. Otherwise they will create a burden on the other banks, by overbidding for and hoarding liquidity.

The exit strategy

Let me turn to the exit strategy. This is an issue on which many have spoken recently. I won’t repeat the arguments which have already been expounded very clearly. The exit strategy has two dimensions. One concerns the non-standard measures which have been implemented to improve the functioning of the transmission mechanism. The other relates to the stance of monetary policy, which can be calibrated through the operations conducted by the central bank.

Let me make a few observations.

First, the decisions to unwind the non-standard measures and to adjust the level of key interest rates can to some extent be separated. In particular, any adjustment to the policy stance will depend on the assessment of the risks to price stability. It can be implemented independently from the stage which has been reached at a given moment in the withdrawal of the non-standard instruments. The withdrawal of a non-standard measure would not necessarily have an impact on the monetary policy stance.

Secondly, a decision about the timing of the exit from the very low level of interest rate requires a close monitoring of all relevant developments. Any measure which could pose an upward risk to price stability will be withdrawn in a timely fashion. In this respect I would prefer not to listen to those who are recommending a bias in deciding the timing of the exit, i.e. that it’s preferable to err on the side of late rather than early withdrawal. It’s pretty obvious that a premature exit may undermine the incipient economic recovery. But a belated response can be equally damaging. This aspect is often underestimated, and rarely studied. Indeed, the later the exit – and the greater the catching-up to be done – the more disruptive the asset price adjustment and the bigger the impact on economic activity.

Thirdly, in assessing whether a given measure should be withdrawn, a central bank should ask itself two questions: are the underlying risks which led it to adopt the measure in the first place still looming? And: could the removal of the measure make such risks reappear? Let me consider the following: interest rates have been brought down to levels close to zero in the face of the sharp recessionary pressures and the risk of deflation. As the economy stabilises and the risks of deflation fade away, partly as a result of the measures taken, the question arises as to whether the exit from the low rates would lead to a re-emergence of the risks of recession and deflation. And there’s another question: could the low level of interest rates, if prolonged, create at some point distortions in financial markets and in the real economy that might complicate the exit?

Just to be concrete, nominal one-year government bond yields in the euro area are currently lower than inflation expectations for the next 12 months. This means negative real rates of return. We have to consider thoroughly the implications this may have for the allocation of resources and the functioning of markets.

These issues have been raised over the past years, and were notably analysed by Raghuram Rajan in his celebrated 2005 Jackson Hole speech. [3] However, little work has been done on this issue since then. Given that the protracted period of low interest rates turned out to be responsible for fuelling the credit bubble which was at the origin of the crisis, research on this issue is urgently needed.

An issue which also deserves attention is the assessment of the policy stance in light of changing underlying macroeconomic conditions. Both the public and market participants tend to assess the policy stance on the basis of the level of the policy rate. The stance is considered to be tightened when the policy rate is raised and loosened when the rate is lowered. In fact, monetary theory suggests that the stance can change even if the policy rate remains unchanged. For instance, with an unchanged policy rate an increase in the projected inflation would imply lower real rates, and thus a more expansionary policy. The same applies for an increase in projected growth.

In other words, keeping the policy rate unchanged when the projected growth rate and inflation rate over the policy-relevant horizon are systematically revised upwards entails a loosening of the policy stance. Policy authorities have thus to judge whether such an easing is appropriate in light of the prevailing conditions, especially if projected inflation is still within the definition of price stability.

One variable that central banks monitor regularly to assess whether a given policy rate may determine an excessively expansionary policy is inflation expectations. Well anchored inflation expectations may reassure policy makers that they can maintain an accommodative policy stance even as the economy recovers. However, experience has shown that measures of inflation expectations have to be taken with great caution. First, inflation expectations might be based on assumptions of a future interest rate path that does not necessarily coincide with the intentions of the central bank. Second, inflation expectations formulated by market participants tend to be influenced by central bank behaviour, to the extent that the former expect the latter to have superior information. In this case inflation expectations remain low as long as the policy rates remain unchanged but are suddenly revised up as the policy rates are increased. The experience of the 1994 interest rate increase by the Fed might be an example of such behaviour by market participants. Finally, in the current situation, more than ever, asset prices tend to be affected by the exceptional measures implemented by central banks and the large flow of capital from Emerging markets. This might distort the extraction of inflation expectations from asset prices. To sum up, central banks should avoid being too complacent when assessing inflation expectations on the basis of measures extracted from long term assets. A broad set of indicators needs to be considered.

Overall, it is appropriate for central banks – and authorities in general – to discuss exit strategies in good time, in order to prepare themselves and the markets adequately. As economic conditions recover and financial markets stabilise, the need for extraordinary monetary policy measures diminishes. But discussing and explaining exit strategies is not the same as implementing them – it serves as a reminder that they will take place and that the exceptional measures will not last for ever. In particular, banks have to start thinking about standing on their own feet as soon as they can, and about resorting to the traditional sources of financing.

Conclusion

Allow me to summarise my main points today. After going through the most synchronised and severe downturn since World War II since last autumn, the global economy is now gradually recovering. But uncertainty is still high.

The situation has improved remarkably quickly in a number of financial markets. But we also have to take into account that the decline was just as fast, and even more dramatic in the months just after the Lehman bankruptcy. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that the recent buoyant developments in asset prices have been driven by the ample liquidity situation in financial markets.

Central banks have done their job. Ample liquidity has been made available to help the euro area economy recover. Looking ahead, and taking into account the improved conditions in financial markets, not all the liquidity measures will be needed to the same extent as in the past. As we have said on a number of occasions, we will make sure that the extraordinary liquidity measures are phased out in a timely and gradual fashion and that this liquidity is absorbed so as to avoid any threat to price stability over the medium to longer term.

What is more important is that the financial sector takes advantage of the current situation to complete its restructuring and equip itself to stand on its own feet so as to support the economy on its way to the recovery. This is the priority at the current juncture.

Thank you for your attention.

Charts

-

[1] I would like to thank E. W. Nordbo, G. Camba-Méndez, I. Cabral and L. Cappiello for their input. I remain responsible for the opinions.

-

[2] See for instance F. Mishkin, “Not all bubbles present a risk to the recovery”, Financial Times, 9 November 2009.

-

[3] Rajan, R. (2005): Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier? Speech delivered at a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Bank Ċentrali Ewropew

Direttorat Ġenerali Komunikazzjoni

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, il-Ġermanja

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Ir-riproduzzjoni hija permessa sakemm jissemma s-sors.

Kuntatti għall-midja