How could a common safe asset contribute to financial stability and financial integration in the banking union?

Published as part of Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, March 2020.

This special feature discusses how a common sovereign safe asset in the euro area could benefit financial stability by fostering financial integration and development, and by changing the structure of asset markets. The discussion focuses on the potential benefits of a well-designed common safe asset that has certain desirable characteristics, while it does not provide an assessment of specific design options. This special feature should be viewed as part of a broader discussion on how to complete the banking union, which also includes considerations regarding a European deposit insurance scheme and changing the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures.

A well-designed common safe asset could benefit financial stability by mitigating the negative feedback loops between sovereigns and their domestic banking sector. First, a common safe asset may foster financial integration in the euro area by facilitating both diversification and de-risking of banks’ sovereign portfolios. In this context, a common safe asset and changes in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures (RTSE) could be two mutually supportive elements of the banking and capital markets union. Second, a common safe asset could foster financial development by introducing an additional financial instrument with a different risk-return profile. This instrument could also allow markets to develop a proper euro area term structure. Third, a common safe asset has the potential to benefit the financial structure by supporting the development of a single securities market in the EU. In addition, a common safe asset could foster the international role of the euro, and would have fundamental implications for the design and implementation of monetary policy in the euro area.

To achieve its intended benefits, a common safe asset should combine several features. It should have a very high credit quality and be resilient to idiosyncratic as well as more widespread sovereign shocks. It should also be compatible with both regulatory and market standards and meet the collateral eligibility criteria for the Eurosystem’s liquidity operations. Furthermore, a common safe asset should not undermine the incentives for sound national fiscal policies, while at the same time ensuring well-functioning national debt markets. A common safe asset should also be of sufficient size and liquidity in order to have a meaningful impact on financial integration and stability. This special feature concludes that a well-designed, common safe asset could be a supportive element of the banking and capital markets union.

1 Motivation

The financial and sovereign debt crises showed that the close link between the resilience of sovereigns and their domestic banking sector in the euro area poses a risk to financial stability. Risk-sharing mechanisms can reduce the impact of country-specific shocks, thus contributing to macroeconomic stability. In a monetary union, risk-sharing mechanisms are particularly important in addressing asymmetric shocks.[1] Enhanced private financial risk sharing can therefore significantly improve the macroeconomic stabilisation of the euro area and thereby the functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The financial and sovereign debt crises showed that this private risk-sharing mechanism did not function properly.[2] Retail lending of banks focused on financing domestic markets, whereas cross-border lending grew ever larger in interbank markets. When stress hit the financial system, this interbank lending was subject to a “sudden stop” and banks’ wholesale activities retrenched into their domestic market.[3] This reinforced fragmentation in financial intermediation and created major feedback loops that tied together the resilience of sovereigns and their domestic banking sector. For example, Andreeva and Vlasopoulos (2016) show that following the onset of the financial crisis, euro area banks started buying sizeable amounts of euro area government debt in a “flight to safety”. Initially they did not discriminate between domestic and non-domestic sovereign debt. This changed during the sovereign crisis, when banks started to only acquire domestic government bonds, shedding those issued by other euro area sovereigns.

A common safe asset could foster financial integration, help mitigate risks spilling over from sovereigns to their domestic banking sector and complement the banking and capital markets union. The achievements under the banking union already limit the extent to which stress in the banking system can spill over from banks to sovereigns, as the framework for single supervision and resolution makes banking sectors more resilient and less dependent on support from national sovereigns. Further progress with the capital markets union will continue to facilitate structural financial integration and – if stepped up – private risk sharing in the EU, making economies less vulnerable to domestic shocks.[4] While these institutional developments contribute substantially to financial stability and reduce the interconnectedness between sovereigns and their domestic banks, there is still the domestic focus of financial markets and banks that may need to be further addressed. As a result, banks remain vulnerable to domestic sovereign risk. If well designed, a common safe asset could facilitate diversification and de-risking of banks’ sovereign portfolios. In addition, a common safe asset may make banks’ funding conditions less dependent on those of the sovereign.

Several proposals for a common safe asset have been put forward and are currently being discussed at the European level. In the aftermath of the financial and sovereign debt crises, several ideas were proposed for the development of a common euro area safe asset. Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018, 2019) provide a comprehensive overview[5] and evaluation of these proposals. In summary, the authors argue that early suggestions were aimed at creating a large liquid euro area bond market to support financial integration and open up funding possibilities for distressed economies. Later proposals focused more on developing a large and liquid supply of euro-denominated safe assets which could substitute some of banks’ holdings of national sovereign debt, thereby mitigating risk spillovers from sovereigns to their respective national banking system.[6] The European Commission has taken an open stance towards exploring the development of a common safe asset, with a view that the development of a common safe asset as well as a revision of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures could facilitate financial integration in the context of the banking and capital markets union.[7] [8] However, there is no consensus on the desirability and design of a common safe asset.

With a view to contributing to the ongoing discussions at the European level, this special feature discusses how a common safe asset could benefit financial stability in the banking union. Section 2 elaborates on how a well-designed common safe asset could facilitate financial integration and help mitigate the negative feedback loops between sovereigns and the domestic banking sector, and how it could support the banking and capital markets union. In this context, Box 1 discusses how a common safe asset might interact with potential changes in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures – another possible measure to reduce the interconnectedness between banks and their domestic sovereign. Section 3 then discusses what conditions need to be met for the common safe asset to achieve the intended benefits. The analysis in Box 1 and Section 3 draws heavily on the work by Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018, 2019). Box B.2 discusses how a common safe asset may extend the benefits of an internationally accepted reserve asset to all members of the banking union. Section 4 concludes. This special feature does not consider the impact of specific safe asset design options, but rather discusses the potential benefits of a theoretical safe asset that has all the desired characteristics. Whether or not all of these characteristics would be feasible is outside the scope of the analysis. The impact of specific safe asset designs on fiscal incentives and the functioning of national debt markets is therefore also outside the scope of this special feature. However, whether a common safe asset ultimately contributes to financial stability strongly depends on its design and regulation. Therefore, further assessment of the potential benefits and drawbacks of specific safe asset proposals by policymakers and academics would benefit the policy discussion going forward.

2 Transmission channels for a common safe asset to benefit financial stability in the banking union

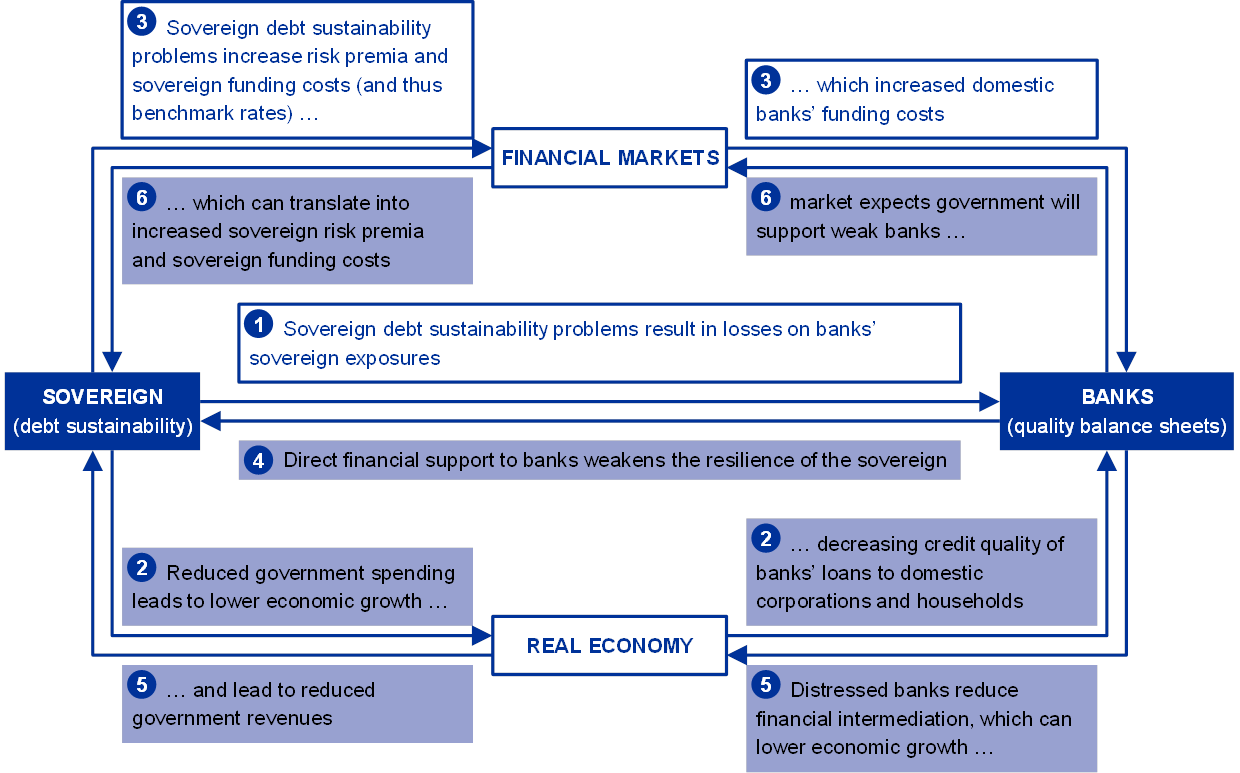

Several transmission channels tie together the resilience of sovereigns and their banking sector. Figure B.1 in this special feature illustrates these channels.[9] Sovereign stress can spill over to the banking sector in various ways. Variations in sovereign credit risk assessments as well as concerns about sovereign debt sustainability could directly lead to increased risk premia and market losses on sovereign debt held by banks (channel 1). In addition, sovereigns with unsustainable debt levels would ultimately need to cut spending, which could lead to lower economic growth and have an adverse impact on the corporates and households to which banks have extended finance (channel 2). Moreover, bank funding costs are closely related to the funding costs of their sovereign, as sovereign funding rates are often used as relevant benchmarks. Also, banks use sovereign bonds as collateral in wholesale transactions, and valuation losses could limit banks’ funding possibilities and increase costs (channel 3). Similarly, problems in the banking sector can spill over to the sovereign. In the absence of credible mechanisms to resolve unviable banks, sovereigns may be compelled to bail out banks that are of systemic importance to their economy (channel 4). This may put a strain on the sovereigns’ finances. Banks in distress are furthermore likely to curb lending to the real economy, which may slow down growth and have a negative impact on government revenues (channel 5). When the market deems it likely that a sovereign may bail out its banking system, this will be reflected by an increase in sovereign funding costs (channel 6).

The development of the banking and capital markets union helps to mitigate the transmission channels between banks and their sovereign, and to improve structural financial integration. Regulators have made significant progress in reducing the bank-to-sovereign contagion channel. The banking union provides the euro area with a harmonised framework for banking supervision at a centralised level, as well as a crisis management and a single resolution mechanism. By increasing the resilience of the banking sector and making it less dependent on national support from the sovereign, the banking union limits the extent to which stress in the banking system can spill over to sovereigns (thereby addressing channels 4 and 6 in Figure B.1). Nevertheless, discussions on a European deposit insurance scheme – a key missing element required to complete the banking union – are still ongoing. Turning to the capital markets union, ongoing initiatives aim to facilitate structural financial integration. The removal of cross-border barriers to investments, diversification of funding (i.e. reducing the overreliance on bank funding) and reducing funding costs will all facilitate risk sharing across the euro area, making economies less vulnerable to domestic shocks. For example, problems in the domestic banking sector will be less detrimental to the domestic economy if a larger share of funding comes from cross-border investors (channel 5).

Figure B.1

Sovereign-banks nexus channels and interactions with a common safe asset

Overview of how problems at the sovereign can spill over to the domestic banking sector and vice versa

Sources: Based on Véron (2017), and Bekooij et al. (2016).

Notes: The figure provides a schematic overview of the channels linking the resilience of a sovereign with its domestic banking sector (channels 1 to 6 in the blue and white boxes). An arrow running from the sovereign to the banking sector indicates a channel through which problems at the sovereign can be transmitted to the banking sector. An arrow running from the banking sector to the sovereign indicates a channel through which problems in the domestic banking sector can spill over to the sovereign. The overview presents direct linkages between the sovereign and the domestic banking sector as well as indirect linkages where the transmission of risks runs via the real economy or financial markets. The transmission channels highlighted in white represent the channels which could be (partially) mitigated by a well-designed common safe asset. The channels in the blue boxes are not affected by a well-designed common safe asset.

However, tackling the sovereign-to-bank channel has proven difficult. A common safe asset could help mitigate this vulnerability. There has been little progress in reducing the sovereign-to-bank contagion channel, as banks are linked to sovereigns both (i) directly through their holdings of sovereign debt and (ii) indirectly via real economy and macroeconomic linkages.[10] However, if well designed, a common safe asset could benefit financial stability by mitigating the negative feedback loops between sovereigns and their domestic banking sector. First, a common safe asset may foster financial integration in the euro area by facilitating both diversification and de-risking of banks’ sovereign exposures. This will make banks less vulnerable to domestic sovereign risk (thereby addressing channel 1 in Figure B.1). Second, a common safe asset could make banks’ funding conditions less dependent on those of the domestic sovereign (channel 3). The euro area financial structure currently lacks a common safe asset. Such a security would develop the financial system by introducing an additional financial instrument with risk-return characteristics different from existing assets, notably with low risk that is not directly related to a single sovereign. A common safe asset could also be used as high-quality liquid collateral and facilitate secured wholesale funding. This would make banks’ funding conditions in the secured interbank market less dependent on the value and credit quality of (national) sovereign bonds. As such, a common safe asset could facilitate financial development and integration, and efficient capital allocation within the euro area. Because diversifying into a common safe asset would make banks less sensitive to idiosyncratic country risk, the risk of flights to safety by banks – as observed during the crisis – may be reduced.

A common safe asset may also facilitate potential risk-mitigating measures aimed at reducing the nexus between sovereigns and banks in the banking union. Recently, several ideas for revising the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures on banks’ balance sheets have been put forward at the global and European level.[11] These ideas have been motivated by the notion that such adjustments could help reduce the interconnectedness between sovereigns and banks. It has been argued[12] that banks cannot create from existing securities a portfolio that has both low concentration and low credit risk by means of diversification alone. Changing the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures may incentivise banks to diversify their sovereign holdings, but this may increase the overall riskiness. A common safe asset could facilitate both diversification and lower credit risk simultaneously.[13] At the same time, a change in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposure may be needed to induce banks to hold a common safe asset. In this regard, a common safe asset and changes in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures could be two mutually supportive measures aimed at reducing the nexus between sovereigns and banks. Box B.1 discusses their possible interaction further.

Finally, a common safe asset has the potential to benefit the financial structure by supporting the development of a single securities market in the EU. Unlike other currency areas, there is currently no pan-European, neutral and harmonised channel for the issuance and initial distribution of debt securities that would cover the European Union as a single domestic market. The fragmentation of debt markets along national lines complicates financial integration and risk sharing among euro area market participants. The potential development of a common safe asset may propel the development of a pan-European service[14] within the EUR liquidity framework of the TARGET Services.[15] At the same time, such an infrastructure would be needed to ensure that investors across the euro area could trade the common safe asset safely and efficiently on a level playing field, independently of their location.

Box B.1

Possible interaction between a common safe asset and the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures

Sovereign exposures currently receive a risk-free treatment in the EU banks’ capital requirements framework. Under Basel standards, jurisdictions may exempt banks from capital requirements for sovereign exposures denominated and funded in the domestic currency.[16] The EU Capital Requirements Regulation[17] (CRR) assigns a zero risk weight to such exposures under the standardised approach.[18] Sovereign exposures are also exempted from large exposure limits, which constrain exposures to a single counterparty to be no greater than 25% of a bank’s own funds. Furthermore, sovereign bonds are treated as high quality liquid bonds under the liquidity requirements.[19]

Several proposals for the revision of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures (RTSE) have been put forward to mitigate the sovereign-bank nexus (see, for example, BCBS (2017) and Véron (2017)).[20] However, no consensus has been reached so far. For our analysis, we focus on the proposals for concentration charges for euro area sovereign exposures.[21] Under these proposals, banks would be incentivised to diversify their sovereign exposures, which may mitigate the sovereign-bank nexus.

As a reaction to concentration charges, banks may diversify their sovereign portfolios by substituting sovereign holdings that are above the concentration threshold with other banks’ sovereign exposures above the threshold. This may reduce banks’ exposures to their domestic sovereign (i.e. “home bias”), thereby mitigating the sovereign-bank nexus. However, it is possible that banks cannot fully diversify their sovereign holdings by trading with each other. In this sense, some sovereign exposures may remain above the concentration threshold.

Concentration charges may also increase the overall riskiness of banks’ sovereign portfolios. Craig et al. (2019) find that the introduction of concentration charges would increase the risk of most banks’ sovereign portfolios after they reallocate their holdings, compared with their current sovereign portfolio. This is also in line with Alogoskoufis and Langfield (2019), who find that reforms focused on concentration would result in banks increasing their overall exposure to sovereign credit risk. While a simultaneous introduction of adequate risk weights could mitigate this risk, their paper finds that banks cannot create from existing securities a sovereign portfolio that has both low concentration and low credit risk by means of diversification only.[22]

A well-designed common safe asset could mitigate some of the unintended consequences of regulatory concentration charges. In a scenario where both concentration charges for sovereign exposures and a common safe asset are in place, banks could substitute parts of their sovereign bond holdings with the common safe asset. As a result, the amount above possible concentration thresholds would be lower and they would only need to redistribute a smaller portion of their sovereign portfolio to avoid concentration charges. Furthermore, due to its low envisaged risk, a common safe asset may lower the overall volatility of banks’ sovereign portfolios following their diversification in response to concentration charges.

This box assesses the extent to which a common safe asset could interact with regulatory concentration charges. We take a two-step approach. In the first step we model the safe asset and banks’ holdings of the safe asset. We consider two different sizes for a European safe asset and compute how much of each euro area country’s government debt would be needed for its creation based on the ECB’s capital key. The total amount of sovereign bonds purchased to reach 30% of GDP would be around €3.5 trillion, while it would be €1.8 trillion to reach 15% of GDP (see Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2019) and Guidice et al. (2019)). [23] With regard to banks’ holdings of the safe asset, we make a number of simplifying assumptions. First, all banks would contribute proportionally to the creation of the safe asset and would replace parts of their sovereign portfolio with a European safe asset.[24] In doing so, we assume that there are no obstacles to banks absorbing the safe asset, and that banks have sufficient incentives to hold it.[25] Second, throughout the analysis, the common safe asset would be exempted from regulatory concentration charges, which largely determines the results of the simulations. In this context, we do not consider any potentially riskier by-product of the common safe asset that could be subject to stricter regulatory treatment. Third, the overall amount of sovereign debt in the aggregate banking system remains constant throughout the analysis.

In the second step, we compare the impact of concentration charges for a scenario with and without a common safe asset. In line with the Basel Committee calibration, we assume concentration charges above 100% of Tier 1 capital.[26] We then simulate how banks would reallocate sovereign bonds above this threshold with other euro area banks.[27] In this reallocation exercise, banks maintain their overall volume of sovereign holdings but aim to reduce holdings above 100% of Tier 1 capital by exchanging these bonds against other euro area banks’ bonds that exceed the threshold.[28] We assume that a bank would only exchange sovereign bonds against bonds that have a similar risk profile. For example, a bank with German sovereign bonds above 100% of its Tier 1 could only trade with a bank that has exposures above this threshold from Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Luxembourg or the Netherlands.[29]

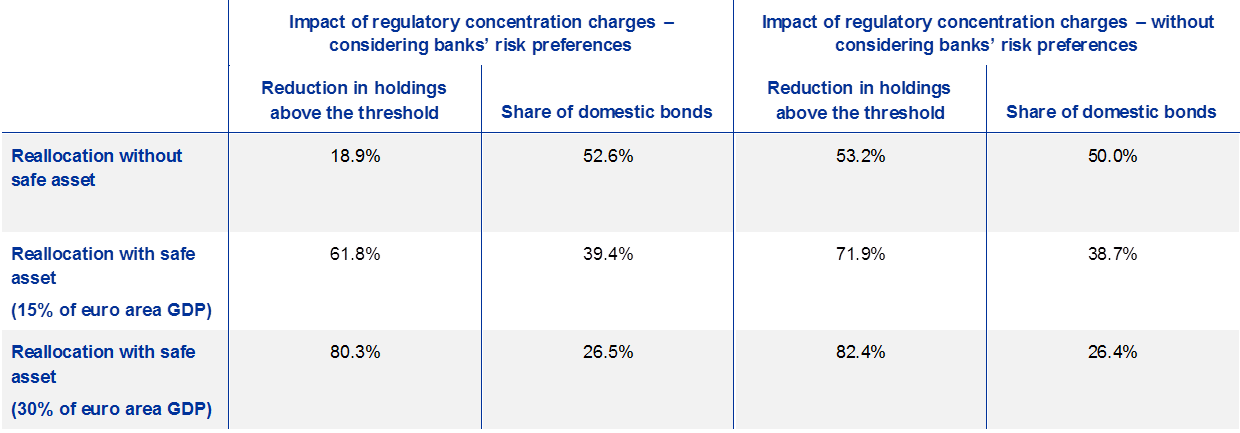

Table A

Potential impact of a common safe asset on banks’ sovereign bond holdings in the event of a regulatory concentration charge (concentration threshold: 100% of T1 capital)

Sources: FINREP and ECB calculations.

Notes: “Reduction in holdings above the threshold” refers to the amount of excess holdings above 100% of T1 capital that could be reduced through banks’ reallocation under three different scenarios: (i) reallocation without a safe asset; (ii) reallocation with a large safe asset (30% of GDP); (iii) reallocation with a smaller safe asset (15% of GDP). “Share of domestic bonds” is the amount invested in domestic sovereign bonds as a percentage of the total amount of euro area sovereign bonds held by banks. Columns 2 and 3 consider banks’ risk preferences meaning that banks only trade sovereign holdings that have a similar credit rating. Columns 4 and 5 do not consider banks’ risk preferences, meaning that banks can trade their sovereign holdings with other sovereign bonds that are above the threshold irrespective of the credit rating.

Table A shows that a common safe asset, which is exempt from regulatory requirements, could reduce euro area banks’ holdings above a concentration threshold of 100% of T1 capital.[30] In the absence of a safe asset, banks could diversify away around 19% of holdings above the threshold in the euro area banking sector, under the assumption that banks only trade in similarly rated bonds (column 2, row 1). If banks could trade their bonds irrespective of the bonds’ credit rating, the banking sectors’ holdings above the threshold could be reduced by around 53% (column 4, row 1). Under the scenario where the safe asset reaches 15% of euro area GDP, banks could diversify around 62% (or 72% without considering banks’ risk preferences) of their bond holdings above the threshold. If the size of the safe asset was 30% of euro area GDP, holdings above the threshold could be reduced to 80% (or 82% without considering banks’ risk preferences). The introduction of a common safe asset would also reduce the share of domestic bonds in banks’ sovereign portfolios (columns 3 and 5). Without a safe asset, banks’ domestic sovereign exposures would amount to around 53% (50% without considering banks’ risk appetite) of total euro area sovereign exposures after banks reallocate their holdings above the regulatory threshold.[31] In the presence of a safe asset, the home bias could be reduced to around 39% or 26%, depending on the scenario for the size of the safe asset.

Chart A

Potential impact of a common safe asset on sovereign portfolio risk in the event of regulatory concentration charges (concentration threshold: 100% of T1 capital)

(sovereign holdings; portfolio variance)

Sources: EBA and ECB calculations.

Notes: Domestic holdings represent banks’ exposure to domestic sovereign bonds, while non-domestic holdings represent exposures to other euro area sovereigns. Portfolio variance is the variance of portfolio returns. In the right panel, white dots indicate portfolio volatility when the returns of the safe assets are the same as the German Bund. Red dots indicate portfolio volatility when the returns of the asset are modelled as a linear combination of the returns of euro area sovereign bonds.

A common safe asset could also reduce banks’ sovereign portfolio variances, thereby mitigating some unintended effects from concentration charges. In line with Craig et al. (2019), the first two panels on the left in Chart A show that concentration charges could increase banks’ sovereign portfolio variance.[32] To see how a safe asset could mitigate this unintended effect, we introduce a safe asset with the same returns as the German Bund (white dots).[33] We find that the resulting reallocations are less volatile than the rebalanced ones across all countries. The effect is larger for the safe asset with a size of 30% of euro area GDP compared with the smaller safe asset.[34] We also assess the impact of a fully diversified asset, assuming that its returns are a linear combination of the returns of euro area sovereign bonds (weighted by each country’s capital key).[35] We find that the resulting sovereign bond portfolio variances would be smaller than the rebalanced ones for most countries except for German and French banks, which in this case would be exposed to countries with lower credit quality.

While a common safe asset could facilitate regulatory concentration charges, the results presented should be interpreted with caution. The findings suggest that a common safe asset could (i) reduce banks’ sovereign holdings above the concentration threshold while keeping the overall amount of sovereign debt in the banking system constant, (ii) reduce banks’ home bias and (iii) lower banks’ portfolio variance, compared with introducing concentration charges without a safe asset. The magnitude of the results depends to a large extent on the calibrations used for the safe asset and on our assumptions of how banks would substitute national sovereign bonds for the common safe asset on their balance sheet. Furthermore, banks’ behaviour is difficult to predict. While we assume that banks try to reallocate holdings to holdings of a similar risk profile, it may also be the case that the presence of a safe asset would incentivise banks to invest their remaining sovereign bond portfolios in riskier bonds. Finally, our results depend on the possible calibration of the RTSE and the assumption that a common safe asset would be exempted from regulatory capital requirements. In this regard, preferential treatment of a common safe asset under the RTSE may incentivise banks to invest in such an asset.[36]

3 Desirable features of a common safe asset

While a common safe asset could foster financial integration and stability in the banking and capital markets union, there is no consensus on how such a common asset should be designed in order for it to have the intended benefits. A wide range of proposals have been put forward. Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018, 2019) provide an overview and comparison of these proposals. This sections draws heavily on their work. Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018, 2019) group the proposals into three broad categories. The first set of proposals envisions the creation of a common safe asset through collective public guarantees. The second requires the creation of an area-wide fiscal authority. In contrast, the third would not rely on fiscal integration but instead suggests the establishment of financial intermediaries to issue a common safe asset backed by a diversified portfolio of euro area sovereign debt. Current discussions at the European level focus on the third group of proposals.

Yet, it seems that there is some common ground as regards the desirable features a common asset should have. A common safe asset should have a very high credit quality and be resilient to idiosyncratic and more widespread sovereign shocks. A common safe asset should have a credit quality comparable to sovereign bonds with the highest credit rating. The safety of a common asset that relies on collective public guarantees or a euro area fiscal authority would be difficult to quantify. Conceptually, however, the robustness of these options to systemic events where the resilience of several sovereigns decreases simultaneously would need to be assessed. In such scenarios, problems may easily spread to sovereigns that have to provide financial support in already unfavourable fiscal conditions. This risk of direct spillovers across sovereigns would not be present for proposals that rely on private risk sharing through diversification and seniority.[37] Studies on the safety of these design options show that there may be a trade-off between safety in severe but plausible events versus extreme crisis scenarios (tail events).[38] For a common safe asset to have a beneficial impact on financial stability in the long term, it would also need to be robust in extreme crisis scenarios since these would be the times that the financial system would need safe assets the most. It should be noted, however, that even a common safe asset resilient to extreme shocks would never be entirely risk free.

A common safe asset should also ensure fiscal discipline without impairing the functioning of national debt markets. Common safe asset designs that depend on loss mutualisation among sovereigns could provide the wrong fiscal incentives, which would run against EU legislation.[39] Some design options which rely on private risk sharing may have a positive impact on fiscal discipline, because they would lead to higher marginal funding costs on remaining national sovereign debt. While this could be a desirable feature of a common safe asset, it may lead to an impairment of the functioning of national debt markets, both in normal times and during future crises. The national debt markets should remain resilient and liquid, and funding costs should not rise prohibitively as a result of the introduction of a common safe asset.[40] [41] In this regard, it has been argued that a rise in funding costs for national sovereign debt might (in part) be offset by lower funding costs for the share of sovereign debt that will enter into the safe asset pool, especially when the common safe asset has an international reserve status (see Box B.2 in this special feature). Finally, cliff-edge effects – for instance due to safe asset design rules that would exclude sovereign debt – should be avoided as this could further hamper sovereigns in regaining market access.[42]

A common asset should be of sufficient size and liquidity in order to have a meaningful impact on financial stability and integration. It has been estimated that a common safe asset based on private risk sharing could – depending on its design – achieve a volume of between 13% and 30% of euro area GDP, while ensuring a very high credit quality.[43] At these levels, a common safe asset would already have a volume larger than the current outstanding German Bund volume (which is about €1.1 trillion) and may have a beneficial impact on financial stability. While the benefits for financial stability may be greater for larger volumes of the common safe asset, there is a clear trade-off between volume and safety. Since common safe asset designs based on private risk sharing rely on subordination to attain high credit quality, a lower subordination level will increase the volume of the safe asset, but also its risk. Besides being of sufficiently large volume and credit quality, the common safe asset should be liquid enough to be used as reference asset for pricing financial assets. In this regard, the common safe asset would need to be issued with various (short-, medium-, and long-term) maturities so that a euro area-wide, risk-free term structure could be constructed.

The creation of a safe asset may pose several challenges to national sovereign debt markets. First, depending on the design, the creation of a common safe asset could have a negative impact on national bond markets should these be perceived to become subordinated to the common safe asset. Second, there could be a trade-off between liquidity of the common safe asset and the remaining national sovereign bond markets. It is possible that the issuance sizes of free-floating national government bond markets will become smaller. This could have a negative impact on market liquidity, potentially reducing the investor base and hampering the price discovery process. These potential challenges to national sovereign debt markets deserve careful consideration.

A common safe asset should also be compatible with both regulatory and market standards. A change in the RTSE may induce the creation of a common safe asset. A common safe asset would then need to have a preferential treatment compared to remaining sovereign debt, in order to incentivise banks to invest in it. Moreover, a common asset should meet the criteria for high-quality liquid assets in line with the applicable regulatory framework. Furthermore, the common safe asset should meet market standards for highly liquid assets in order to be fungible as collateral in, for instance, repo or derivative transactions.

In addition to meeting the above criteria, any common safe asset must be eligible for central bank operations to be universally acknowledged as a euro-area safe asset. The eligibility of a common safe asset as collateral for the Eurosystem’s monetary policy operations would incentivise banks to hold such an asset, and would moreover be key for the reputation of the European institutions. Whether a common safe asset would be eligible under the current collateral framework depends on its design. Currently, the collateral framework of the Eurosystem would only accept common safe assets in the form of unsecured debt instruments issued by a group of states or an agency such that they can be classified as supranational or sovereign debt securities. However, if the safe asset is created as a contractual innovation, for instance in the form of a securitisation, it would not be eligible. Although some types of secured debt instruments are eligible (see ECB Guideline (EU) 2015/510[44]), the Eurosystem currently does not accept secured debt instruments that are backed by sovereign bonds.

Box B.2

International demand for a common safe asset

An often-cited feature of the euro bond market is that ample domestic and international demand for safe sovereign assets is barely met by a decelerating supply. Owing to downgrades of significant euro area sovereign issuers to lower investment grade and high-yield ratings as well as fiscal consolidation of highly rated issuers, the supply of sovereign assets deemed safe by investors has not kept up with the growing demand. Domestic and international central bank purchases add to the scarcity of highly rated sovereign assets, putting further upward pressure on their prices. As a result, bond yields across euro area sovereigns have become more dispersed over the recent decade, with issuers of safe sovereign assets benefiting from a scarcity premium.

This box provides evidence on demand for a common safe asset and explains the benefits of a broader supply of the common safe assets from the perspective of the issuer. It argues that a larger supply of highly rated sovereign assets would likely be absorbed by domestic and international demand mainly because its typical investors, the official sector in particular, are relatively less price-sensitive. As such, the benefits of lower borrowing rates can be transmitted to a larger set of issuers and strengthen the international role of the euro at the same time. However, whether this will translate into lower average sovereign funding costs also depends on adjustments in the supply of lower-rated sovereign assets which, in turn, is determined by the specific safe asset design as well as developments in fiscal consolidation of single euro area sovereigns.

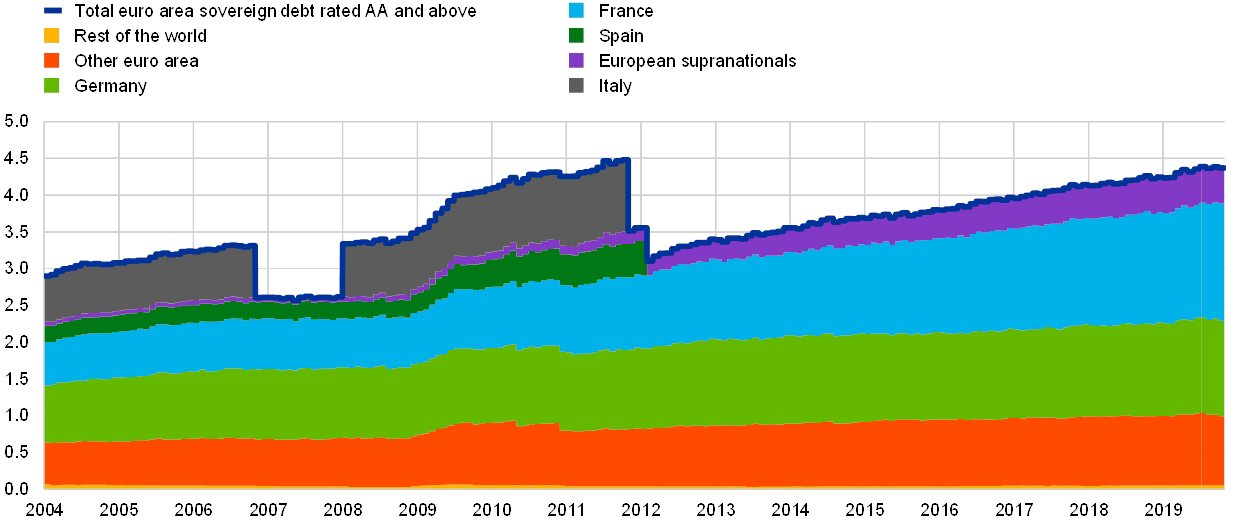

The supply of highly rated sovereign bonds grows only gradually. From a regulatory viewpoint, all sovereign bonds are regarded as high quality and liquid assets (HQLA). However, market participants do not share this perception of safety, as evidenced by the flight-to-quality dynamics during the sovereign crisis. Instead, they focus on assets that are relatively very low-risk (e.g. AAA or AA rating) and have a deep and liquid secondary market. Furthermore, investors tend to consider securities issued by governments or large public institutions safer than those issued by private sector institutions, all other things being equal. According to this classification, only a very narrow set of sovereign assets can be considered safe. In the euro area, the nominal stock of (sub-sovereign debt securities rated AAA and AA stands at roughly €4.5 trillion, which is still slightly below the peak in 2011 before the onset of the euro area sovereign debt crisis (Chart A). In comparison, US general government debt has increased by nearly a third in nominal terms over the same time span.

Chart A

Decrease in nominal supply of highly rated euro area sovereign bonds

(EUR billions)

Sources: Iboxx.

Note: Sovereign and sub-sovereign debt rated AA and above by S&P. The discontinuity in the series is explained by intermittent rating downgrades and upgrades.

Data on holdings of euro area sovereign assets reveal that foreign investors tend to invest mainly in securities issued by countries that are simultaneously low-risk and with a sizeable economy. Table A illustrates the strong preferences of foreign investors for holding low-risk, highly liquid securities. Indeed, German and French sovereign bonds are held in significantly higher proportions than other sovereigns, followed by the Netherlands. Demand for bonds of a similar risk profile issued by smaller countries (Austria and Belgium) is significantly weaker. Moreover, foreign investors show little interest in lower-rated bonds that are relatively riskier, irrespective of the liquidity of their secondary market. Evidence from the IMF’s Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) suggests that the bulk of these portfolio inflows originate from the official sector, in particular regarding the holdings of highly rated debt. The demand from this investor group is known to be driven by precautionary considerations, which makes it more stable and price-insensitive than demand from investors targeting a certain absolute portfolio return.

Table A

Foreign official investors make up a significant share of highly rated and highly liquid euro area sovereign debt market

Sources: SHS, IMF.

Notes: The table indicates the share of (sub-)sovereign assets issued in the respective country that is held by investors not reporting to the Eurosystem in the context of the Securities Holdings Statistics (SHS), corrected for holdings by the Eurosystem via the public sector purchase programme.

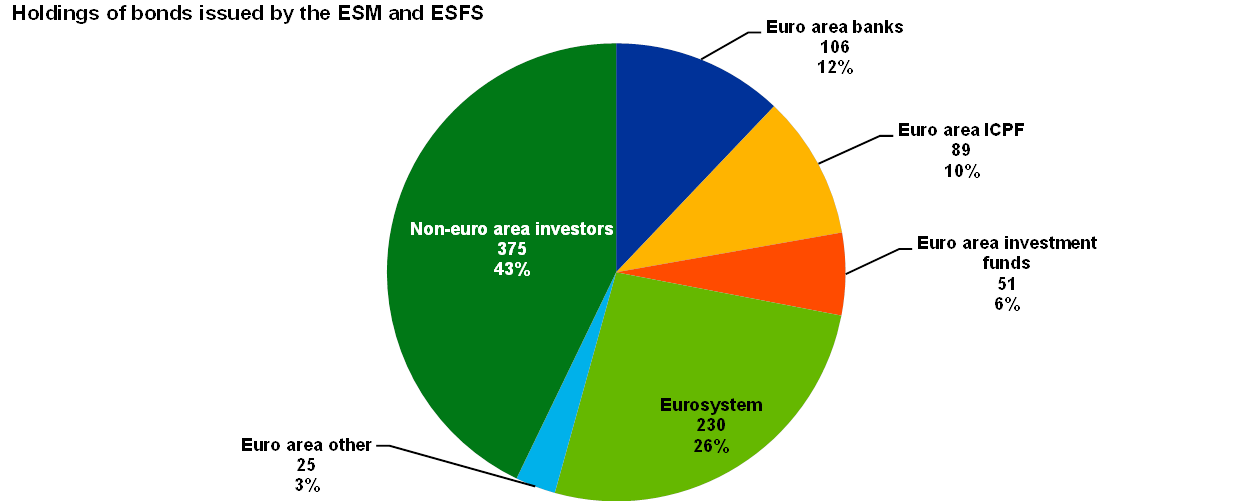

Foreign investors might be particularly interested in holding a common (safe) asset. Euro-denominated bonds, issued by European supranational organisations such as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) are arguably the closest to a safe sovereign asset. Holding statistics on these bonds reveal that foreign investors are particularly active in this market segment, with their share exceeding those of individual member states’ sovereign bonds (Chart B). The most attractive feature of these bonds is that they provide a foreign investor with an exposure to the euro area as a whole rather than to individual member states, thereby reducing the monitoring costs. In addition to the high credit rating and high levels of liquidity, international investors may prefer to own an asset representative of the whole currency area, instead of having to get acquainted with the differences in economic fundamentals of individual countries. According to anecdotal evidence, price-insensitive official sector investors also likely represent a large fraction of the foreign demand in the market for supranational bonds. A highly rated and liquid euro area-wide security could thus generate significant interest from international investors, potentially raising portfolio flows into the euro sovereign bond markets.

Chart B

Foreign investors pose large demand for euro denominated supranational bonds

(EUR billions; percentages)

Sources: ECB.

Note: Holdings of bonds issued by the ESM and the ESFS reported in the ECB Securities Holdings Statistics (SHS).

Available evidence on safe euro area sovereign bonds suggests that international investors, central banks in particular, are eager to own highly rated euro area debt, likely reflecting precautionary purposes.[45] However, the introduction of a euro area safe asset would likely come with a price impact on the existing national sovereign bonds. Lower yields may be transmitted to a broad set of euro area issuers, especially those of less liquid sovereign bonds boasting strong economic fundamentals. A significant share of these bonds would be transformed into higher-rated securities, as part of the common safe asset, and buyers of the safe asset would also indirectly hold them. Hence, to the extent that there is a positive net flow of funds into the safe asset from foreign investors, their absolute holdings of lower-rated sovereign bonds would increase, possibly lowering funding costs. On the other hand, any additional supply of highly rated sovereign bonds would, all other things being equal, raise government yields in this segment, reversing to some extent the scarcity premium on German Bunds or other top-rated sovereign bonds. Given the limited price sensitivity of international official investors active in this segment, this price impact may, however, be limited.

Nevertheless, the effect on overall sovereign funding costs remains uncertain. Whether the broader supply of safe sovereign assets ultimately translates into lower overall financing costs for euro area sovereigns depends on the particular design of the safe asset as well as on price adjustments to a changing rating structure of the euro sovereign bond market.[46] Under some proposals, the transformation of sovereign credit risk into a safe asset takes place on the secondary market (e.g. via pooling and tranching) and would be neutral to sovereign financing costs and the functioning of national sovereign bond markets. This would make it possible to reap the benefits of the increased demand from internationals investors as discussed above. Under alternative designs, the safe asset would be created by guaranteeing a proportion of outstanding debt from all sovereign issuers. In such cases, yields on national sovereign bonds would rise, as they would automatically become junior to the safe asset, and countries with weak fundamentals might face an overall increase in borrowing costs. A significant rise in their national sovereign bond yields could potentially outweigh the benefits of the safe asset and larger purchase volumes from international investors.

4 Concluding remarks

A well-designed common safe asset could benefit financial stability in the banking union by mitigating the negative feedback loops between sovereigns and their domestic banking sector. The extent to which these benefits will materialise will depend on the design features of the safe asset as well as the regulatory treatment of the common safe assets and remaining sovereign debt. A common safe asset should have a very high credit quality and be resilient to idiosyncratic as well as more widespread sovereign shocks. A common safe asset market should also be liquid and of sufficient size in order to have a meaningful impact on financial integration and stability. Furthermore, a common safe asset should not undermine the incentives for sound national fiscal policies, while at the same time ensuring the proper functioning of national debt markets.

This special feature finds that a sufficiently large and well-designed common safe asset may facilitate a substantial diversification in the banking system’s sovereign bond holdings in the presence of concentration charges. Box B.1 suggests that a common safe asset could reduce banks’ (i) sovereign holdings above the concentration threshold while keeping the overall amount of sovereign debt in the banking system constant, (ii) home bias, and (iii) sovereign portfolio variance, relative to introducing concentration charges without a safe asset. These results should be interpreted with caution, however, as they depend on a number of simplifying assumptions.

Moreover, there could be considerable domestic and international demand for a common safe asset, which would make it possible to extend the benefits of lower funding costs to a broader set of euro area sovereigns and lift the international role of the euro. However, whether this translates into lower average sovereign funding costs also depends on adjustments in the demand and supply of lower-rated sovereign assets which, in turn, is determined by the specific safe asset design as well as developments in fiscal consolidation of single euro area sovereigns.

To achieve its intended effects, a common safe asset would need to be implemented in a prudent manner. Special attention should be paid to the regulatory treatment of a common safe asset and the treatment of remaining sovereign debt. If well designed, a common safe asset warrants preferential treatment and may thereby incentivise the take-up and development of this market. Moreover, a resilient common safe asset contributing to integration could be further supported by a pan-European infrastructure to facilitate the efficient allocation and pricing of the asset, regardless of the location of issuers and investors. Finally, further consideration should be given to the potential impact of a common safe asset on the functioning of national sovereign markets to avoid unintended effects, both in normal times and during crises.

5 References

Alogoskoufis, S., Langfield, S. (2019), “Regulating the doom loop”, VoxEU, October.

Andreeva, D.C, Vlasopoulos, T. (2016), “Home bias in bank sovereign bond purchases and the bank-sovereign nexus”, Working Paper Series, No 1977, ECB, November.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017), “The regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures”, BCBS Discussion Paper.

Beck, Thorsten, Wagner, Wolf and Uhlig, Harald (2011), Insulating the financial sector from the European debt crisis: Eurobonds without public guarantees, VoxEU, September.

Bekooij, J., Frost J., van der Molen, R. and Muzalewski, K. (2016), Hazardous tango: Sovereign-bank interdependencies across countries and time, DNB working paper 541.

Bellia, M., Calès, L., Frattarolo, L., Maerean, A., Monteiro, D., Petracco Guidici, M., Vogel, L. (2019), “The Sovereign-Bank Nexus in the Euro Area: Financial and Real Channels”, EC Discussion Paper, 122, November.

Brunnermeier, M. K., Langfield, S., Pagano M., Reis, R., van Nieuwerburgh, S,. Vayanos, D. (2017), “ESBies: Safety in the Tranches”, Economic Policy, 32, No 90: pp. 175 -219 [Earlier version available as ESRB Working Paper No 21, September 2016].

Constâncio, V. (2018), “Why EMU requires more financial integration”, Keynote speech at the joint conference of the European Commission and European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, 3 May.

Craig, B., Giuzio, M., Paterlini, S. (2019), “The effect of possible EU diversification requirements on the risk of banks’ sovereign bond portfolio”, ESRB Working Paper Series, No 89.

De Grauwe, P., Moesen, W. (2009), “Gains for All: A proposal for a common Eurobond”. CEPS commentary, April 3. Brussels: Center for European Policy Studies.

Delpla, J., von Weizsäcker, J.( 2010). “The Blue Bond Proposal”. Bruegel Policy Brief 2010/03. Brussels: Bruegel.

European Central Bank (2016), “Special Feature A – Financial integration and risk sharing in a monetary union”, Financial integration in Europe 2016.

European Commission (2015), Completing Europe’s economic and monetary union.

European Commission (2017), Reflection paper on the deepening of the economic and monetary union.

European Systemic Risk Board (2018), “Sovereign bond-backed securities: a feasibility study. Volume I: main findings” (by the ESRB High-Level Task Force on Safe Assets).

German Council of Economic Experts (2018), “Advancing banking and capital markets union more decisively”, GCEE Annual Report.

Giudice, Gabriele, de Manuel, Mirzha, Kontolemis, Zenon G. and Monteiro, Daniel P. (2019), A European Safe Asset to Complement National Government Bonds.

Gräb, J., Kostka, T. Quint, D. (2019), “Quantifying the exorbitant privilege – potential benefits from a stronger international role of the euro”, Special feature in the report of the International Role of the Euro, ECB, June.

Hellwig, Christian, and Thomas Philippon (2011), Eurobills, not Eurobonds, VoxEU, 2 December.

Leandro, A., Zettelmeyer, J. (2018), “The search for a euro area safe asset”, Working Paper Series, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Leandro, A., Zettelmeyer, J. (2019), Creating a euro area safe asset without mutualising risk (much).

Monti, Mario (2010), A New Strategy for the Single Market. Report to the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, May.

The Next CMU High-Level Group (2019), Savings and Sustainable Investment Union.

Véron, N. (2017), Sovereign Concentration Charges: A New Regime for Banks’ Sovereign Exposures [Provided in the context of Economic Dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup in ECON].

- See European Commission (2015), ECB (2016), Constâncio (2018).

- In its 2017 reflection paper on the deepening of the EMU, the European Commission points out that the convergence trends observed in the initial years of the EMU were partly illusionary and driven by a mispricing of risk. The financial crisis led to a strong market correction and fragmentation of euro area financial markets.

- See ECB (2016) for an assessment of how and under what conditions financial integration benefits social welfare. The authors argue that cross-border equity holdings, foreign direct investment and cross-border retail lending in particular are resilient forms of financial integration which enable income and consumption smoothing by making countries less dependent on domestic financing.

- See European Commission (2015, 2017), and Next CMU High-Level Group (2019).

- Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018) provide an overview of several proposals, including proposals by De Grauwe and Moesen (2009), Monti (2010), Delpla and von Weizsäcker (2010), Beck, Wagner and Uhlig (2011), Hellwig and Philippon (2011), Brunnermeier et al. (2017).

- This categorisation was made by Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2019), p. 2.

- In President’s Junker’s letter of intent at the State of the Union in September 2017 and the Banking Union Communication of October 2017, the European Commission highlighted the potential for a common safe asset and made a commitment to take action in this area. In May 2018, the Commission presented a legislative proposal to enable the development of a market for sovereign bond-backed securities (SBBS). The proposal draws on the findings of an ESRB report on SBBS which was published in 2018. In April 2019, the European Parliament endorsed the proposed reforms to facilitate SBBS.

- In its 2017 reflection paper on the deepening of the EMU, the Commission states that changing the regulatory treatment of sovereign bonds on banks’ balance sheets could also be discussed as an option to reduce the sovereign-bank nexus.

- The description of transmission channels draws strongly on the work by Véron (2017) and Bekooij et al. (2016).

- Bellia et al. (2019).

- See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017) and Véron (2017).

- See Alogoskoufis and Langfield (2019).

- The ways to achieve low credit risk in a common safe asset vary between different safe asset design proposals. In all of them, however, some other entity will have to bear the sovereign credit risk.

- In May 2019, the ECB issued a market consultation to investigate why there is currently no pan-European channel for the issuance and distribution of debt securities. In October 2019, the ECB published the responses it had received from the market. The Eurosystem will keep market participants informed regarding the progress of its work with a view to determining any follow-up actions leading to a potential Eurosystem initiative in this area. In doing so, the Eurosystem will take into account all relevant legal, regulatory and statutory considerations.

- By November 2022, TARGET Services will comprise a single liquidity pool in central bank money, i.e. a cash account with the Eurosystem, which would enable financial market actors to manage transactions in payments (retail and large value), securities and collateral. Within this context, an issuance and initial distribution service could potentially be explored in order to issue and distribute common safe assets, among other debt instruments, in an efficient way across the euro area.

- See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017).

- Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 1).

- See Article 114(4) of the CRR (Regulation (EU) No 575/2013). In addition, the CRR grants authorities the discretion to allow internal ratings-based (IRB) banks to use the standardised approach for their sovereign exposures.

- See Article 400(1a) of the CRR.

- The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017) mentions the removal of the IRB approach for sovereign exposures, positive standardised risk weights for most sovereign exposures, the introduction of marginal risk weight add-ons to mitigate concentration risk, and the removal of the national discretion to apply a haircut of zero for sovereign repo-style transactions.

- The proposal considered here does not take into account differences in credit risk. German Council of Economic Experts (2018) analysed the effects of risk-based concentration charges.

- The focus of this box is on safe assets, not the design of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. The design and calibration of the RTSE would need to be assessed in a different context.

- We assume that this volume represents the safe part of the common safe asset. We do not consider any potential riskier by-product that could result from creating a common safe asset. In other words, we assume that banks do not hold any subordinated or junior sovereign debt.

- By way of example, if the creation of the common safe asset requires x% of country X’s government debt to be included in the safe asset creation pool, we assume that banks would contribute proportionally to their holdings of country X’s debt. A bank holding y% of country X’s government debt would sell x%*y% government bonds to the entity that creates the safe asset.

- For instance, it has been suggested that a change in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposure may be needed to induce banks to hold a common safe asset.

- Given that exposures below the 100% threshold would be exempted from capital charges in this scenario, we assume that banks would not aim to diversify these exposures. Therefore, the reshuffling exercise only takes into account the sovereign bonds that are above the concentration threshold.

- The algorithm starts with a random bank’s sovereign exposure that is above the concentration threshold. It then chooses a sovereign bond above the threshold from another bank. Starting from the sovereign with the most similar rating, exchanges are pursued until the concentration threshold is reached for this sovereign. The holdings offloaded are allocated to the set of banks offering their holdings above the threshold, ensuring that receiving banks do not breach the concentration threshold. After the maximum reallocation possible is completed for this bank-sovereign bond pair, the algorithm moves to the next pair in random order.

- This analysis takes into account the (limited) outstanding amounts of general government debt securities held by banks.

- The other buckets include ES, IE, LT, LV, MT, SI, SK (A+ to A-), CY, IT, PT (BBB+ to BBB-), and GR (BB+ to B-), based on Q4 2018 S&P credit ratings. We assume that banks only exchange bonds against bonds that are in the same credit bucket.

- In our model, stricter concentration charges would lead to more sovereign holdings above the threshold and the need to further reduce domestic sovereign bond holdings. Since the size of the safe asset and the absorption by banks is fixed and independent of the concentration threshold, the relative impact of a safe asset under a stricter concentration charge is slightly lower.

- Since we assume that banks only reshuffle those sovereign holdings that are above the regulatory threshold, a large share of sovereign bonds are not redistributed. Therefore, the aggregate home bias in euro area banking system still stays relatively high based on the simulation exercise.

- Portfolio variance is interpreted as the “average riskiness” of banks’ portfolios (Craig et al., 2019).

- This assumption derives from the literature which suggests that the safe asset should have lower returns than any euro area sovereign bond.

- This finding is in line with those of the ESRB (2018, p. 15), who find that banks would de-risk their sovereign bond portfolios (without reducing the size of those portfolios) if they reinvested (some fraction of) current holdings into senior SBBS.

- Under these assumptions, the safe asset would be equal to a diversified euro area sovereign bond portfolio.

- The preferential treatment should only extended to safe part of the common asset and not to any subordinated elements.

- As mentioned in Section 2 and Box 1, a common safe asset that relies on diversification as well as seniority may outperform pure diversification only, as pure diversification could reduce banks’ home bias but may not result in overall lower credit risk in banks’ sovereign portfolio. See also Alogoskoufis and Langfield (2019) and Craig et al. (2019).

- Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2019), pp. 25 -28, compare different design options for European Safe Bonds (ESBies) and e-bonds, and show that while ESBies might be slightly safer in severe events (>1.7% VAR threshold), they would be substantially less safe in extreme tail events (<1.7% VAR threshold).

- Loss mutualisation among sovereigns would not be in line with the Treaty, as Article 125 TFEU states that “A Member State shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local, or other public authorities […] or public undertakings of another Member State […]”.

- Markets should also remain stable during future shocks and crises, as turbulence of national bond markets may increase rather than decrease financial stability risk. See ESRB (2018).

- See Giudice et al. (2019) for an assessment of the e-bond proposal on marginal and average funding costs. They conclude that marginal funding costs would rise only moderately for e-bond volumes up to 20% of GDP. Average funding costs would remain broadly unchanged up to 45% of GDP. This is because of the assumption that higher funding costs of remaining national debt would be offset by more favourable funding conditions for the e-bond debt. The ESRB (2018) concludes that the impact on national sovereign bond market liquidity is limited to a senior SBBS volume of up to 13% of GDP.

- Under some proposals for a common safe asset, only bonds from sovereigns that have primary market access can be included in the safe asset.

- See Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2019), Giudice et al. (2019).

- Guideline (EU) 2015/510 of the European Central Bank of 19 December 2014 on the implementation of the Eurosystem monetary policy framework (ECB/2014/60) (OJ L 91, 2.4.2015, p. 3).

- See Gräb et al. (2019).

- The two most developed safe assets proposals, SBBS and e-bonds, have important differences in their set-up and effects on national funding costs. SBBS is entirely a pass-through vehicle and should be neutral to yields. E-bonds guarantee a fixed interest rate for the senior component of national sovereign bonds, reducing funding costs for some countries and increasing them for others.