1 Introduction

Since 1 January 1999 the euro has been introduced in 19 EU Member States; this report examines seven of the eight EU countries that have not yet adopted the single currency. One of the eight countries, Denmark, has notified the Council of the European Union (EU Council) of its intention not to participate in Stage Three of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).[1] As a consequence, Convergence Reports only have to be provided for Denmark if the country so requests. Given the absence of such a request, this report examines the following countries: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden. All seven countries are committed under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter the “Treaty”)[2] to adopt the euro, which implies that they must strive to fulfil all the convergence criteria.

In producing this report, the ECB fulfils its requirement under Article 140 of the Treaty. Article 140 says that at least once every two years, or at the request of an EU Member State with a derogation, the ECB and the European Commission must report to the EU Council “on the progress made by the Member States with a derogation in fulfilling their obligations regarding the achievement of economic and monetary union”. The seven countries under review in this report have been examined as part of the regular two-year cycle. The European Commission has also prepared a report, and both reports are being submitted to the EU Council in parallel.

In this report, the ECB uses the framework applied in its previous Convergence Reports. It examines, for the seven countries concerned, whether a high degree of sustainable economic convergence has been achieved, whether the national legislation is compatible with the Treaties and the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank (Statute), and whether the statutory requirements are fulfilled for the relevant national central bank (NCB) to become an integral part of the Eurosystem.

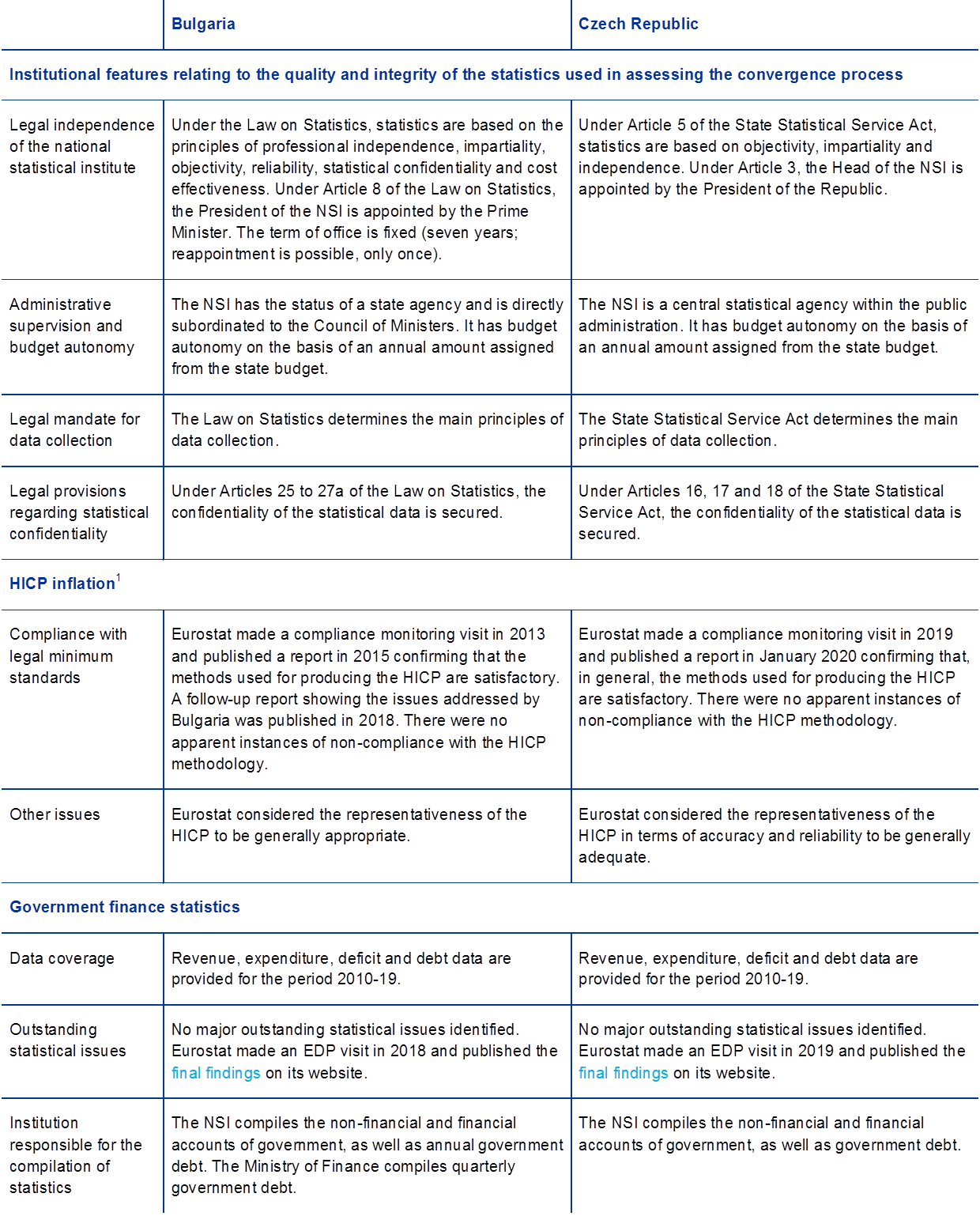

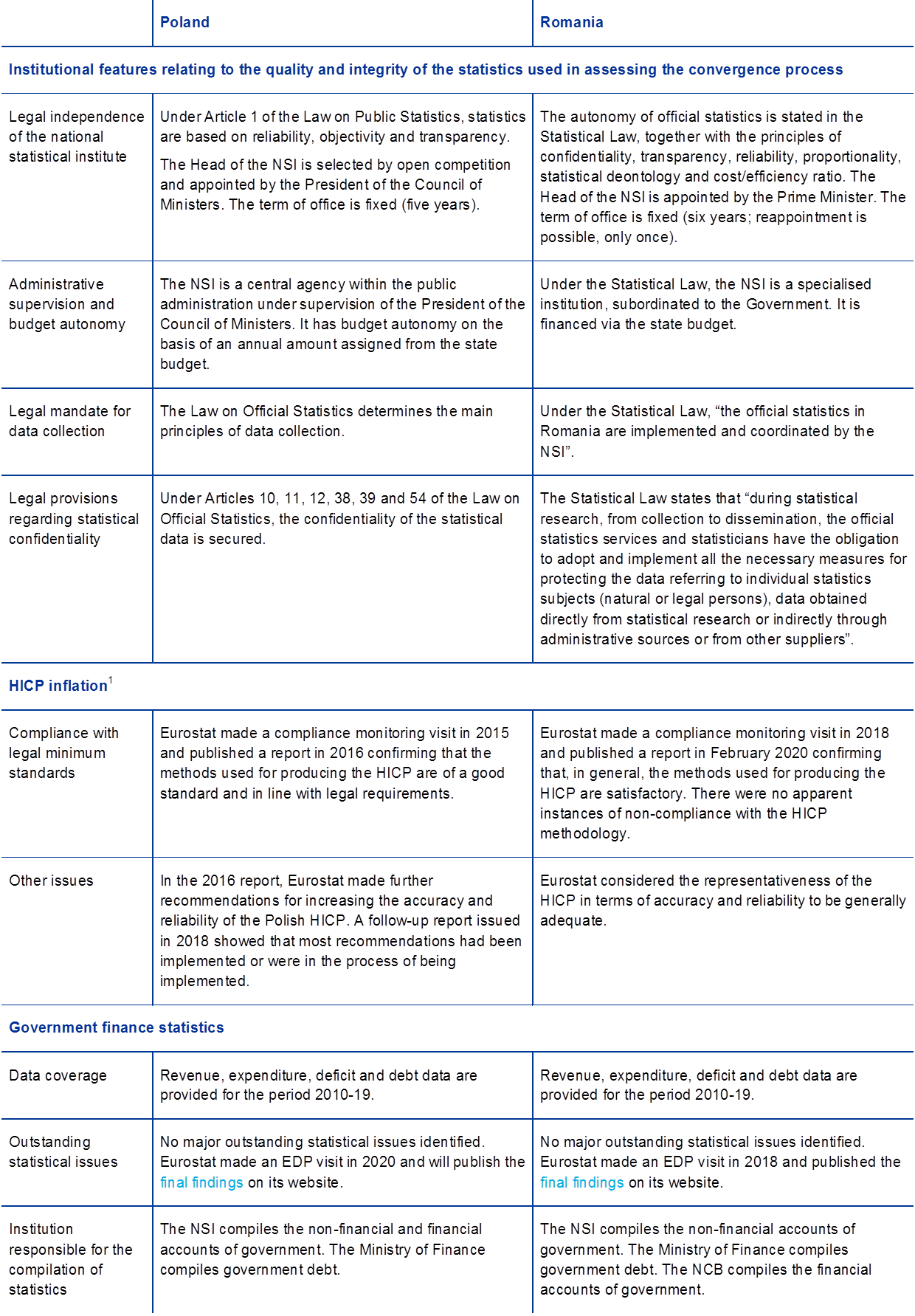

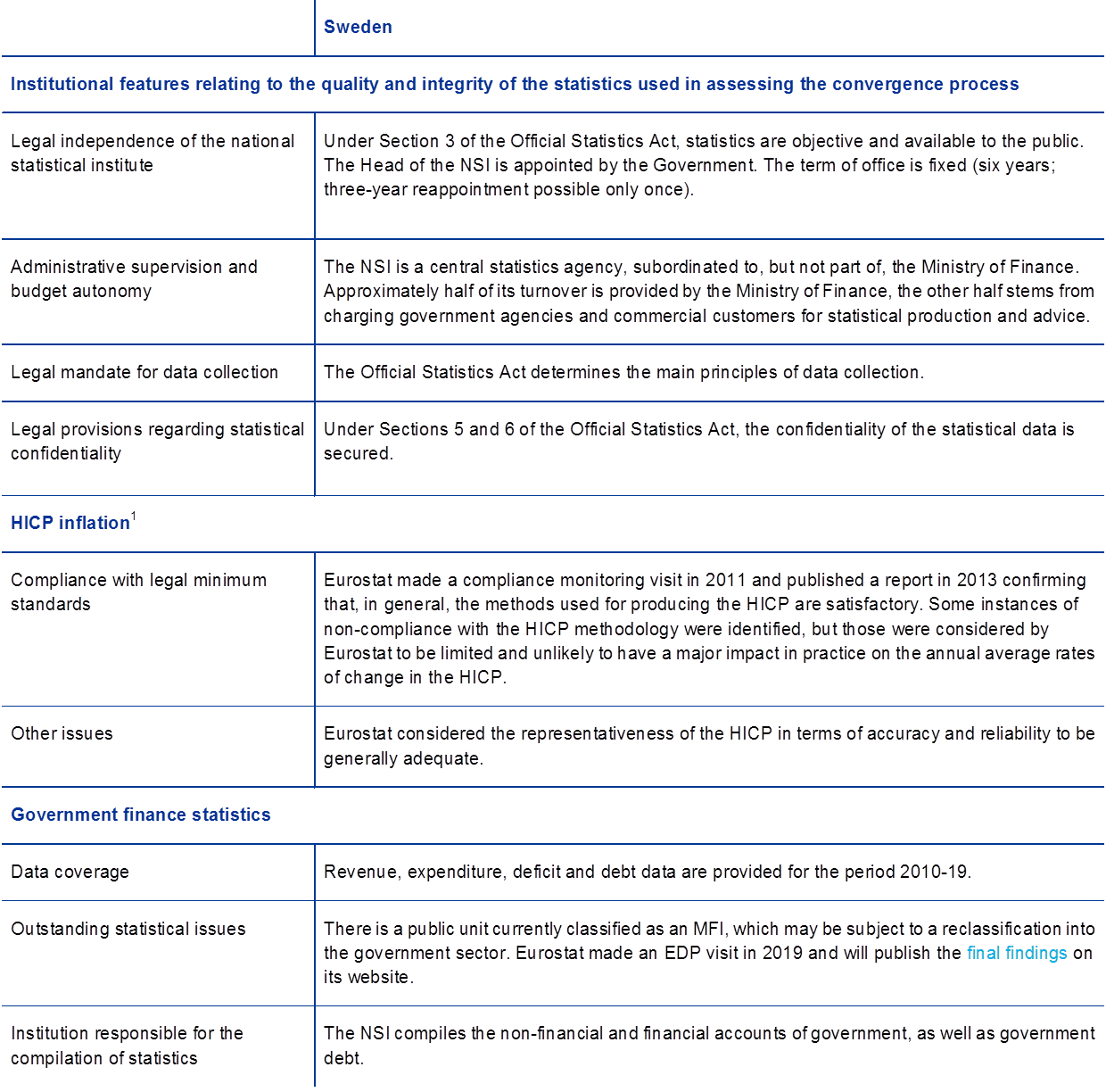

The examination of the economic convergence process is highly dependent on the quality and integrity of the underlying statistics. The compilation and reporting of statistics, particularly government finance statistics, must not be subject to political considerations or interference. EU Member States have been invited to consider the quality and integrity of their statistics as a matter of high priority, to ensure that a proper system of checks and balances is in place when these statistics are compiled, and to apply minimum standards in the domain of statistics. These standards are of the utmost importance in reinforcing the independence, integrity and accountability of the national statistical institutes and in supporting confidence in the quality of government finance statistics (see Chapter 6).

It should be also recalled that, from 4 November 2014 onwards,[3] any country whose derogation is abrogated must join the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) at the latest on the date on which it adopts the euro. From then on all SSM-related rights and obligations apply to that country. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that the necessary preparations are made. In particular, the banking system of any Member State joining the euro area, and therefore the SSM, will be subject to a comprehensive assessment.[4]

This report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 describes the framework used for the examination of economic and legal convergence. Chapter 3 provides a horizontal overview of the key aspects of economic convergence. Chapter 4 contains the country summaries, which provide the main results of the examination of economic and legal convergence. Chapter 5 examines in more detail the state of economic convergence in each of the seven EU Member States under review. Chapter 6 provides an overview of the convergence indicators and the statistical methodology used to compile them. Finally, Chapter 7 examines the compatibility of the national legislation of the Member States under review, including the statutes of their NCBs, with Articles 130 and 131 of the Treaty.

2 Framework for analysis

2.1 Economic convergence

To examine the state of economic convergence in EU Member States seeking to adopt the euro, the ECB makes use of a common framework for analysis. This common framework, which has been applied in a consistent manner throughout all European Monetary Institute (EMI) and ECB Convergence Reports, is based, first, on the Treaty provisions and their application by the ECB with regard to developments in prices, fiscal balances and debt ratios, exchange rates and long‑term interest rates, as well as in other factors relevant to economic integration and convergence. Second, it is based on a range of additional backward and forward‑looking economic indicators considered to be useful for examining the sustainability of convergence in greater detail. The examination of the Member State concerned based on all these factors is important to ensure that its integration into the euro area will proceed without major difficulties. Boxes 1 to 5 below briefly outline the legal provisions and provide methodological details on the application of these provisions by the ECB.

This report builds on principles set out in previous reports published by the ECB (and prior to that by the EMI) in order to ensure continuity and equal treatment. In particular, a number of guiding principles are used by the ECB in the application of the convergence criteria. First, the individual criteria are interpreted and applied in a strict manner. The rationale behind this principle is that the main purpose of the criteria is to ensure that only those Member States with economic conditions conducive to the maintenance of price stability and the coherence of the euro area can participate in it. Second, the convergence criteria constitute a coherent and integrated package, and they must all be satisfied; the Treaty lists the criteria on an equal footing and does not suggest a hierarchy. Third, the convergence criteria have to be met on the basis of actual data. Fourth, the application of the convergence criteria should be consistent, transparent and simple. Moreover, when considering compliance with the convergence criteria, sustainability is an essential factor, as convergence must be achieved on a lasting basis and not just at a given point in time. For this reason, the country examinations elaborate on the sustainability of convergence.

In this respect, economic developments in the countries concerned are reviewed from a backward‑looking perspective, covering, in principle, the past ten years. This helps to better determine the extent to which current achievements are the result of genuine structural adjustments, which in turn should lead to a better assessment of the sustainability of economic convergence.

In addition, and to the extent appropriate, a forward‑looking perspective is adopted. In this context, particular attention is paid to the fact that the sustainability of favourable economic developments hinges critically on appropriate and lasting policy responses to existing and future challenges. Strong governance, sound institutions and sustainable public finances are also essential for supporting sustainable output growth over the medium to long term. Overall, it is emphasised that ensuring the sustainability of economic convergence depends on the achievement of a strong starting position, the existence of sound institutions and the pursuit of appropriate policies after the adoption of the euro.

The common framework is applied individually to the seven EU Member States under review. These examinations, which focus on each Member State’s performance, should be considered separately, in line with the provisions of Article 140 of the Treaty.

The cut‑off date for the statistics included in this Convergence Report was 7 May 2020. The statistical data used in the application of the convergence criteria were provided by the European Commission (see Chapter 6 as well as the tables and charts), in cooperation with the ECB in the case of exchange rates and long‑term interest rates. In agreement with the European Commission, the reference period for the price stability criterion is from April 2019 to March 2020. Similarly, the reference period for the long‑term interest rate criterion is also from April 2019 to March 2020. For exchange rates, the reference period is from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2020. Historical data on fiscal positions cover the period up to 2019. Account is also taken of forecasts from various sources, together with the most recent convergence programme of the Member State concerned and other information relevant to a forward‑looking examination of the sustainability of convergence. The European Commission’s Spring 2020 Economic Forecast[5] and the Alert Mechanism Report 2020, which are also taken into account in this report, were released on 6 May 2020 and 17 December 2019, respectively. This report was adopted by the General Council of the ECB on 4 June 2020.

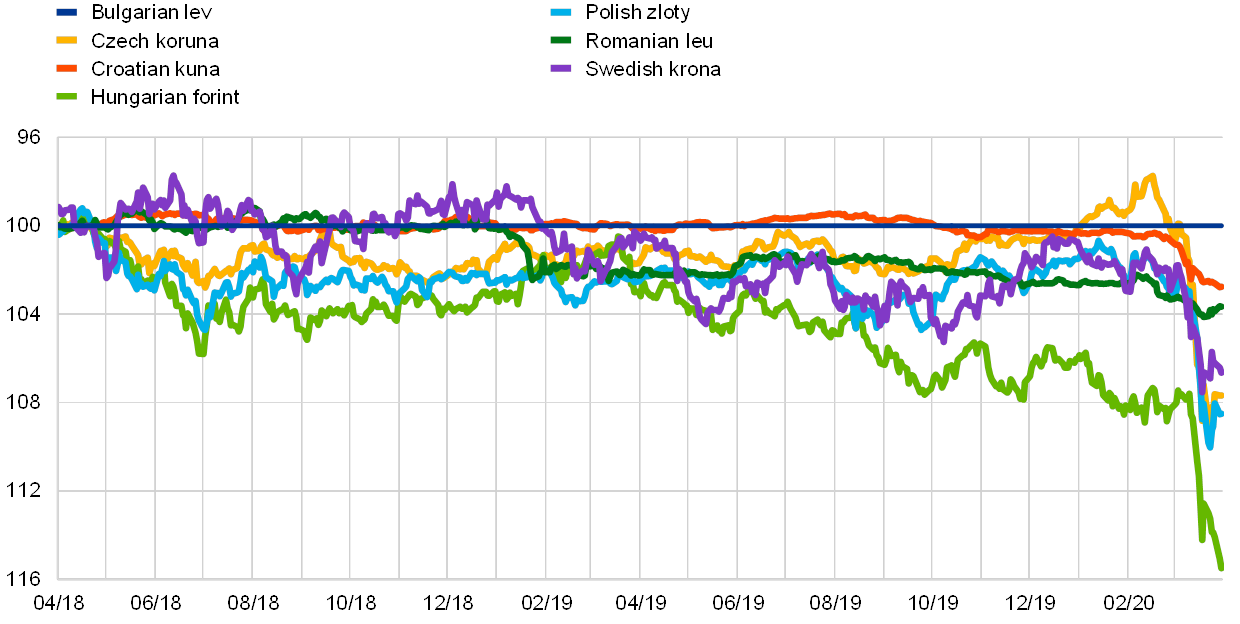

This Convergence Report considers the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the convergence assessment only to a very limited extent. As it is too early to draw any firm conclusions about how the convergence paths will be affected and whether this effect will materialise in a symmetric or asymmetric way across the relevant countries, detailed analysis will be conducted in the context of the next Convergence Report. In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the forward-looking convergence assessment is surrounded by high uncertainty, and the full impact can only be evaluated ex post. Most EU Member States introduced containment measures to bring down the number of infections and also implemented special fiscal, macroprudential, supervisory and monetary policy measures to mitigate the economic impact. The implications for statistical data are also not fully understood at this stage. The heightened uncertainty relates to all convergence criteria. As regards the price stability criterion, there is a high level of uncertainty as to how inflation is going to evolve over the coming months. In particular, the economic downturn brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic could be more protracted or the recovery could be faster than previously expected. Considerable uncertainty surrounds the balance of risks between downward pressures on inflation linked to weaker demand and upward pressures related to supply disruptions. Regarding the fiscal criterion, the COVID-19 pandemic has an impact on the outlook for general government finances, while the key fiscal indicators from 2010 to 2019 are not affected. As regards the fiscal outlook, the ECB’s analysis relies mostly on the European Commission’s Spring 2020 Economic Forecast, which, for all countries under review, shows a sharp deterioration in the government balance resulting from the marked deterioration in economic activity and the fiscal measures implemented to mitigate the crisis. Nevertheless, the potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for the medium to long-term sustainability of budgetary positions beyond its impact on the latest forecasts are not covered because of the high levels of uncertainty. In particular, the ECB’s analysis relies on the European Commission’s 2019 Debt Sustainability Monitor, which was released prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Exchange rate volatility and depreciation pressures on national currencies vis-à-vis the euro increased after the emergence of COVID-19. In order to limit distortions to the overall convergence assessment, the review period for exchange rate developments ends in March 2020. For long-term interest rate developments, April 2020 is excluded from the analysis owing to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on financial markets. Extreme levels of uncertainty and volatility in financial markets may cloud the information content of financial market developments and, therefore, introduce potential distortions in the overall assessment of each country’s convergence process. In conclusion, a proper analysis of the economic impact of the pandemic on the convergence assessment can only be performed in retrospect.

With regard to price developments, the legal provisions and their application by the ECB are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1 Price developments

1. Treaty provisions

Article 140(1), first indent, of the Treaty requires the Convergence Report to examine the achievement of a high degree of sustainable convergence by reference to the fulfilment by each Member State of the following criterion:

“the achievement of a high degree of price stability; this will be apparent from a rate of inflation which is close to that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”.

Article 1 of Protocol (No 13) on the convergence criteria stipulates that:

“The criterion on price stability referred to in the first indent of Article 140(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union shall mean that a Member State has a price performance that is sustainable and an average rate of inflation, observed over a period of one year before the examination, that does not exceed by more than 1½ percentage points that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability. Inflation shall be measured by means of the consumer price index on a comparable basis taking into account differences in national definitions”.

2. Application of Treaty provisions

In the context of this report, the ECB applies the Treaty provisions as outlined below.

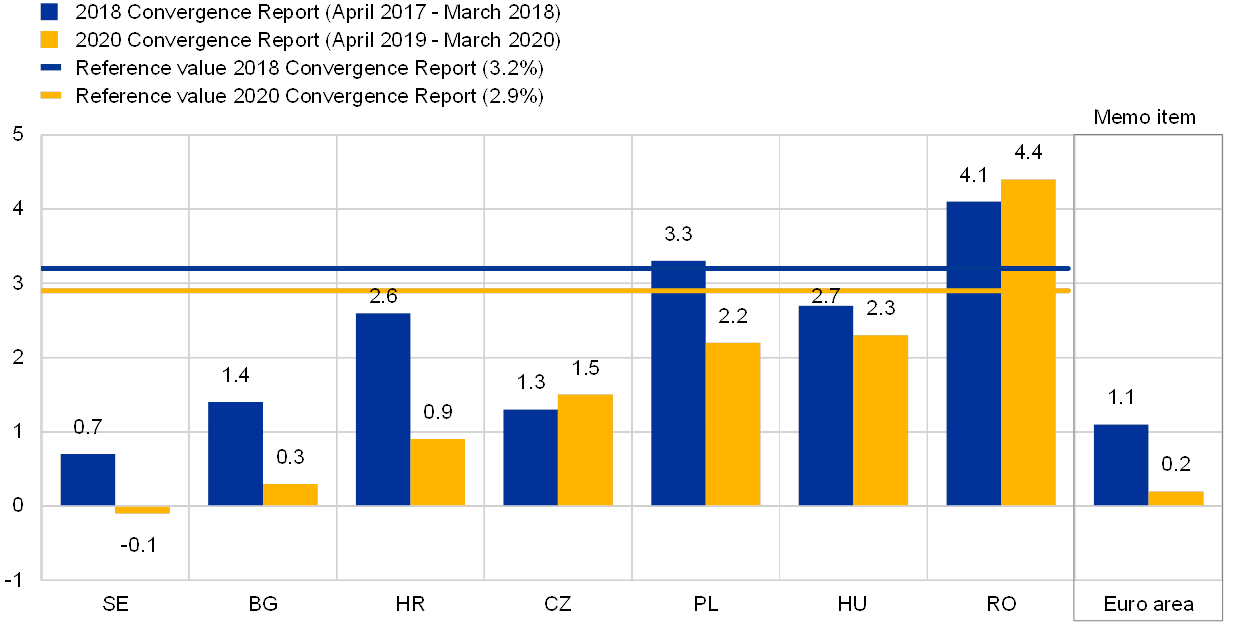

First, with regard to “an average rate of inflation, observed over a period of one year before the examination”, the inflation rate has been calculated using the change in the 12‑month average of the HICP in the reference period from April 2019 to March 2020 compared with the previous 12‑month average.

Second, the notion of “at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”, which is used for the definition of the reference value, has been applied by taking the unweighted arithmetic average of the rates of inflation of the following three Member States: Portugal (0.2%), Cyprus (0.4%) and Italy (0.4%). As a result, adding 1½ percentage points to the average rate, the reference value is 1.8%. It should be stressed that under the Treaty a country’s inflation performance is examined in relative terms, i.e. against that of other Member States. The price stability criterion thus takes into account the fact that common shocks (stemming, for example, from global commodity prices) can temporarily drive inflation rates away from central banks’ targets.

In the last five reports, the “outlier” approach was used to deal appropriately with potential significant distortions in individual countries’ inflation developments. A Member State is considered to be an outlier if two conditions are fulfilled: first, a country’s 12‑month average inflation rate is significantly below the comparable rates in other Member States; and, second, a country’s price developments have been strongly affected by exceptional factors. In this report, none of the Member States with the lowest inflation rates was identified as an outlier.

Inflation has been measured on the basis of the HICP, which was developed for the purpose of assessing convergence in terms of price stability on a comparable basis (see Section 2 of Chapter 6).

The average rate of HICP inflation over the 12‑month reference period from April 2019 to March 2020 is reviewed in the light of the country’s economic performance over the last ten years in terms of price stability. This allows a more detailed examination of the sustainability of price developments in the country under review. In this connection, attention is paid to the orientation of monetary policy, in particular to whether the focus of the monetary authorities has been primarily on achieving and maintaining price stability, as well as to the contribution of other areas of economic policy to this objective. Moreover, the implications of the macroeconomic environment for the achievement of price stability are taken into account. Price developments are examined in the light of supply and demand conditions, focusing on factors such as unit labour costs and import prices. Finally, trends in other relevant price indices are considered. From a forward-looking perspective, a view is provided of prospective inflationary developments in the coming years, including forecasts by major international organisations and market participants. Moreover, institutional and structural aspects relevant for maintaining an environment conducive to price stability after adoption of the euro are discussed.

With regard to fiscal developments, the legal provisions and their application by the ECB, together with procedural issues, are outlined in Box 2.

Box 2 Fiscal developments

1. Treaty and other legal provisions

Article 140(1), second indent, of the Treaty requires the Convergence Report to examine the achievement of a high degree of sustainable convergence by reference to the fulfilment by each Member State of the following criterion:

“the sustainability of the government financial position; this will be apparent from having achieved a government budgetary position without a deficit that is excessive as determined in accordance with Article 126(6)”.

Article 2 of Protocol (No 13) on the convergence criteria stipulates that:

“The criterion on the government budgetary position referred to in the second indent of Article 140(1) of the said Treaty shall mean that at the time of the examination the Member State is not the subject of a Council decision under Article 126(6) of the said Treaty that an excessive deficit exists”.

Article 126 sets out the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). In accordance with Article 126(2) and (3), the European Commission prepares a report if a Member State does not fulfil the requirements for fiscal discipline, in particular if:

- the ratio of the planned or actual government deficit to GDP exceeds a reference value (defined in the Protocol on the EDP as 3% of GDP), unless either:

- the ratio has declined substantially and continuously and reached a level that comes close to the reference value; or, alternatively,

- the excess over the reference value is only exceptional and temporary and the ratio remains close to the reference value;

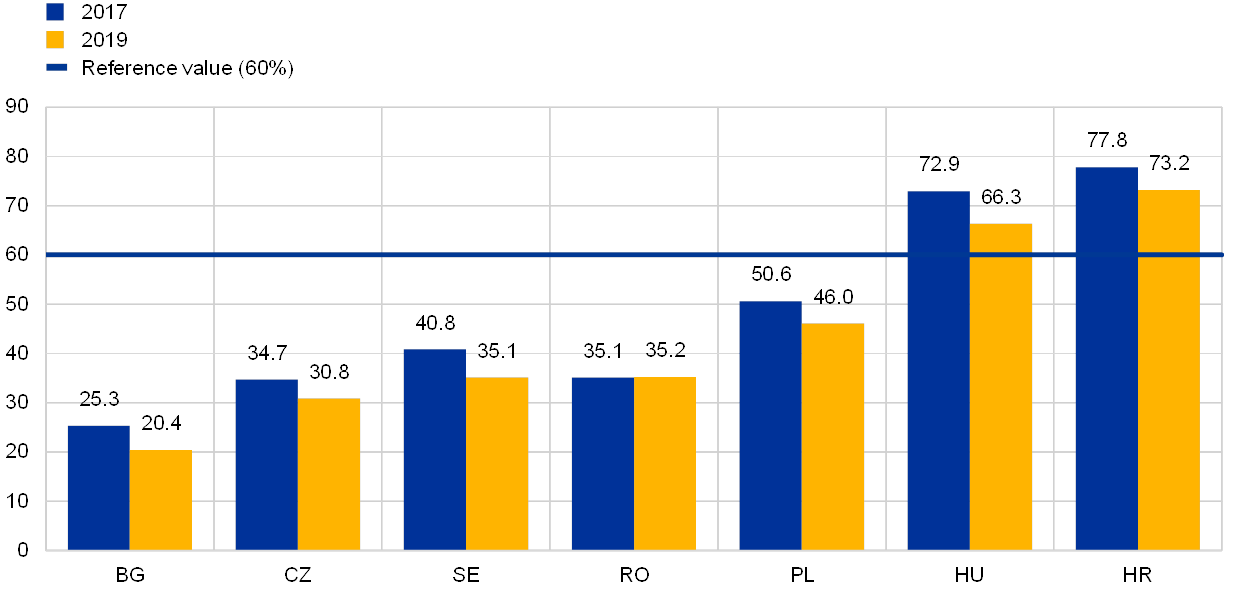

- the ratio of government debt to GDP exceeds a reference value (defined in the Protocol on the EDP as 60% of GDP), unless the ratio is sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace.

In addition, the report prepared by the Commission must take into account whether the government deficit exceeds government investment expenditure and all other relevant factors, including the medium‑term economic and budgetary position of the Member State. The Commission may also prepare a report if, notwithstanding the fulfilment of the criteria, it is of the opinion that there is a risk of an excessive deficit in a Member State. The Economic and Financial Committee formulates an opinion on the Commission’s report. Finally, in accordance with Article 126(6), the EU Council, on the basis of a recommendation from the Commission and having considered any observations which the Member State concerned may wish to make, decides, acting by qualified majority and excluding the Member State concerned, and following an overall assessment, whether an excessive deficit exists in a Member State.

The Treaty provisions under Article 126 are further clarified by Regulation (EC) No 1467/97[6] as amended by Regulation (EU) No 1177/2011[7], which, among other things:

- confirms the equal footing of the debt criterion with the deficit criterion by making the former operational, while allowing for a three‑year period of transition for Member States exiting EDPs opened before 2011. Article 2(1a) of the Regulation provides that when it exceeds the reference value, the ratio of the government debt to GDP shall be considered sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace if the differential with respect to the reference value has decreased over the previous three years at an average rate of one twentieth per year as a benchmark, based on changes over the last three years for which the data are available. The requirement under the debt criterion shall also be considered to be fulfilled if the required reduction in the differential looks set to occur over a defined three‑year period, based on the Commission’s budgetary forecast. In implementing the debt reduction benchmark, the influence of the economic cycle on the pace of debt reduction shall be taken into account;

- details the relevant factors that the Commission shall take into account when preparing a report under Article 126(3) of the Treaty. Most importantly, it specifies a series of factors considered relevant in assessing developments in medium‑term economic, budgetary and government debt positions (see Article 2(3) of the Regulation and, below, details on the ensuing ECB analysis).

Moreover, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (TSCG), which builds on the provisions of the enhanced Stability and Growth Pact, entered into force on 1 January 2013.[8] Title III (Fiscal Compact) provides, among other things, for a binding fiscal rule aimed at ensuring that the general government budget is balanced or in surplus. This rule is deemed to be respected if the annual structural balance meets the country‑specific medium‑term objective and does not exceed a deficit – in structural terms – of 0.5% of GDP. If the government debt ratio is significantly below 60% of GDP and risks to long‑term fiscal sustainability are low, the medium‑term objective can be set at a structural deficit of at most 1% of GDP. The TSCG also includes the debt reduction benchmark rule referred to in Regulation (EU) No 1177/2011, which amended Regulation (EC) No 1467/97. The signatory Member States are required to introduce in their constitution – or equivalent law of higher level than the annual budget law – the stipulated fiscal rules accompanied by an automatic correction mechanism in case of deviation from the fiscal objective.

2. Application of Treaty provisions

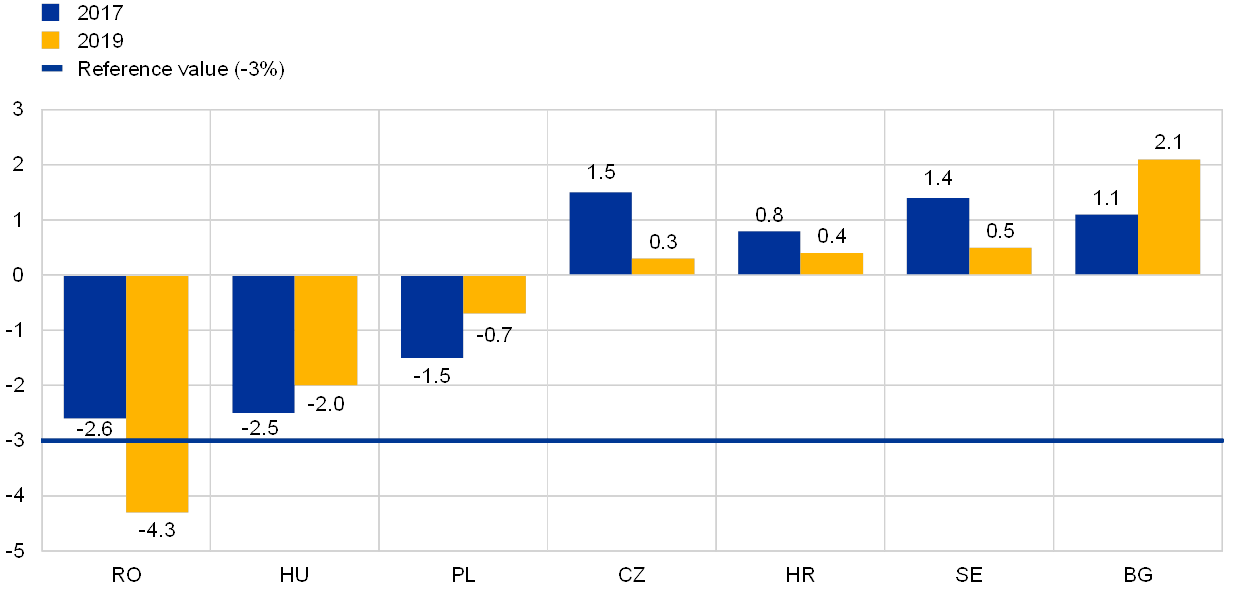

For the purpose of examining convergence, the ECB expresses its view on fiscal developments. With regard to sustainability, the ECB examines key indicators of fiscal developments from 2010 to 2019, the outlook and the challenges for general government finances, focusing on the links between deficit and debt developments. Regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on general government finances, the ECB refers to the Stability and Growth Pact’s general escape clause, which was activated on 20 March 2020. In particular, for the preventive arm, Articles 5(1) and 9(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1466/97[9] state that “in periods of severe economic downturn for the euro area or the Union as a whole, Member States may be allowed temporarily to depart from the adjustment path towards the medium-term budgetary objective …, provided that this does not endanger fiscal sustainability in the medium term”. For the corrective arm, Articles 3(5) and 5(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 stipulate that “in the case of a severe economic downturn in the euro area or in the Union as a whole, the Council may also decide, on a recommendation from the Commission, to adopt a revised recommendation under Article 126(7) TFEU provided that this does not endanger fiscal sustainability in the medium term”. The ECB also provides an analysis with regard to the effectiveness of national budgetary frameworks, as referred to in Article 2(3)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 and in Directive 2011/85/EU.[10] With regard to Article 126, the ECB, in contrast to the Commission, has no formal role in the EDP. Therefore, the ECB report only states whether the country is subject to an EDP.

With regard to the Treaty provision that a debt ratio of above 60% of GDP should be “sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace”, the ECB examines past and future trends in the debt ratio. For Member States in which the debt ratio exceeds the reference value, the ECB provides the European Commission’s latest assessment of compliance with the debt reduction benchmark laid down in Article 2(1a) of Regulation (EC) No 1467/97.

The examination of fiscal developments is based on data compiled on a national accounts basis, in compliance with the European System of Accounts 2010 (ESA 2010) (see Chapter 6). Most of the figures presented in this report were provided by the Commission in April 2020 and include government financial positions from 2010 to 2019 as well as Commission forecasts for 2020‑21.

With regard to the sustainability of public finances, the outcome in the reference year, 2019, is reviewed in the light of the performance of the country under review over the past ten years. First, the development of the deficit ratio is investigated. It is useful to bear in mind that the change in a country’s annual deficit ratio is typically influenced by a variety of underlying forces. These influences can be divided into “cyclical effects” on the one hand, which reflect the reaction of deficits to changes in the economic cycle, and “non‑cyclical effects” on the other, which are often taken to reflect structural or permanent adjustments to fiscal policies. However, such non‑cyclical effects, as quantified in this report, cannot necessarily be seen as entirely reflecting a structural change to fiscal positions, because they include temporary effects on the budgetary balance stemming from the impact of both policy measures and special factors. Indeed, assessing how structural budgetary positions have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic is particularly difficult in view of uncertainty over the level and growth rate of potential output.

As a further step, the development of the government debt ratio in this period is considered, as well as the factors underlying it. These factors are the difference between nominal GDP growth and interest rates, the primary balance and the deficit‑debt adjustment. Such a perspective can offer further information on the extent to which the macroeconomic environment, in particular the combination of growth and interest rates, has affected the dynamics of debt. It can also provide more information on the contribution of the structural balance and the cyclical developments, as reflected in the primary balance, and on the role played by special factors, as included in the deficit‑debt adjustment. In addition, the structure of government debt is considered, by focusing in particular on the shares of debt with a short‑term maturity and foreign currency debt, as well as their development. By comparing these shares with the current level of the debt ratio, the sensitivity of fiscal balances to changes in exchange rates and interest rates can be highlighted.

Turning to a forward‑looking perspective, national budget plans and recent forecasts by the European Commission for 2020‑21 are considered, and account is taken of the medium‑term fiscal strategy, as reflected in the convergence programme. This includes an assessment of the projected attainment of the country’s medium‑term budgetary objective, as foreseen in the Stability and Growth Pact, as well as of the outlook for the debt ratio on the basis of current fiscal policies. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the general escape clause has been activated and allows deviations from the medium-term budgetary objective as described in Box 2. In addition, long‑term challenges to the sustainability of budgetary positions and broad areas for consolidation are emphasised, particularly those related to the issue of unfunded government pension systems in connection with demographic change and to contingent liabilities incurred by the government. The potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for the medium to long-term sustainability of budgetary positions beyond its impact on the latest forecasts are not covered because of the high levels of uncertainty. Furthermore, in line with past practice, the analysis described above also covers most of the relevant factors identified in Article 2(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1467/97, as described in Box 2.

With regard to exchange rate developments, the legal provisions and their application by the ECB are outlined in Box 3.

Box 3 Exchange rate developments

1. Treaty provisions

Article 140(1), third indent, of the Treaty requires the Convergence Report to examine the achievement of a high degree of sustainable convergence by reference to the fulfilment by each Member State of the following criterion:

“the observance of the normal fluctuation margins provided for by the exchange‑rate mechanism of the European Monetary System, for at least two years, without devaluing against the euro”.

Article 3 of Protocol (No 13) on the convergence criteria stipulates that:

“The criterion on participation in the Exchange Rate mechanism of the European Monetary System referred to in the third indent of Article 140(1) of the said Treaty shall mean that a Member State has respected the normal fluctuation margins provided for by the exchange‑rate mechanism on the European Monetary System without severe tensions for at least the last two years before the examination. In particular, the Member State shall not have devalued its currency’s bilateral central rate against the euro on its own initiative for the same period”.

2. Application of Treaty provisions

With regard to exchange rate stability, the ECB examines whether the country has participated in ERM II (which superseded the ERM as of January 1999) for a period of at least two years prior to the convergence examination without severe tensions, in particular without devaluing against the euro. In cases of shorter periods of participation, exchange rate developments are described over a two‑year reference period.

The examination of exchange rate stability against the euro focuses on the exchange rate being close to the ERM II central rate, while also taking into account factors that may have led to an appreciation, which is in line with the approach taken in the past. In this respect, the width of the fluctuation band within ERM II does not prejudice the examination of the exchange rate stability criterion.

Moreover, the issue of the absence of “severe tensions” is generally addressed by: (i) examining the degree of deviation of exchange rates from the ERM II central rates against the euro; (ii) using indicators such as exchange rate volatility vis‑à‑vis the euro and its trend, as well as short‑term interest rate differentials vis‑à‑vis the euro area and their development; (iii) considering the role played by foreign exchange interventions; and (iv) considering the role of international financial assistance programmes in stabilising the currency.

The reference period in this report is from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2020. All bilateral exchange rates are official ECB reference rates (see Chapter 6).

In addition to ERM II participation and nominal exchange rate developments against the euro over the period under review, evidence relevant to the sustainability of the current exchange rate is briefly reviewed. This is derived from the development of the real effective exchange rates and the current, capital and financial accounts of the balance of payments. The evolution of gross external debt and the net international investment position over longer periods is also examined. The section on exchange rate developments further considers measures of the degree of a country’s integration with the euro area. This is assessed in terms of both external trade integration (exports and imports) and financial integration. Finally, the section on exchange rate developments reports, if applicable, whether the country under examination has during the two-year reference period benefited from central bank liquidity assistance or balance of payments support, either bilaterally or multilaterally with the involvement of the IMF and/or the EU. Both actual and precautionary assistance are considered, including access to precautionary financing in the form of, for instance, the IMF’s Flexible Credit Line.

With regard to long‑term interest rate developments, the legal provisions and their application by the ECB are outlined in Box 4.

Box 4 Long‑term interest rate developments

1. Treaty provisions

Article 140(1), fourth indent, of the Treaty requires the Convergence Report to examine the achievement of a high degree of sustainable convergence by reference to the fulfilment by each Member State of the following criterion:

“the durability of convergence achieved by the Member State with a derogation and of its participation in the exchange‑rate mechanism being reflected in the long‑term interest‑rate levels”.

Article 4 of Protocol (No 13) on the convergence criteria stipulates that:

“The criterion on the convergence of interest rates referred to in the fourth indent of Article 140(1) of the said Treaty shall mean that, observed over a period of one year before the examination, a Member State has had an average nominal long‑term interest rate that does not exceed by more than two percentage points that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability. Interest rates shall be measured on the basis of long‑term government bonds or comparable securities, taking into account differences in national definitions”.

2. Application of Treaty provisions

In the context of this report, the ECB applies the Treaty provisions as outlined below.

First, with regard to “an average nominal long‑term interest rate” observed over “a period of one year before the examination”, the long‑term interest rate has been calculated as an arithmetic average over the latest 12 months for which HICP data were available. The reference period considered in this report is from April 2019 to March 2020, in line with the reference period for the price stability criterion.

Second, the notion of “at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”, which is used for the definition of the reference value, has been applied by using the unweighted arithmetic average of the long‑term interest rates of the same three Member States included in the calculation of the reference value for the criterion on price stability (see Box 1). Over the reference period considered in this report, the long‑term interest rates of the three countries with the lowest inflation rate included in the calculation of the reference value for the price stability criterion were 0.5% (Portugal), 0.8% (Cyprus) and 1.6% (Italy). As a result, the average rate is 0.9% and, adding 2 percentage points, the reference value is 2.9%. Interest rates have been measured on the basis of available harmonised long‑term interest rates, which were developed for the purpose of examining convergence (see Chapter 6).

As mentioned above, the Treaty makes explicit reference to the “durability of convergence” being reflected in the level of long‑term interest rates. Therefore, developments over the reference period from April 2019 to March 2020 are reviewed against the background of the path of long‑term interest rates over the past ten years (or otherwise the period for which data are available) and the main factors underlying differentials vis‑à‑vis the average long‑term interest rate prevailing in the euro area. During the reference period, the average euro area long‑term interest rate may have partly reflected high country‑specific risk premia in several euro area countries. Therefore, the euro area AAA long‑term government bond yield (i.e. the long‑term yield of the euro area AAA yield curve, which includes the euro area countries with an AAA rating) is also used for comparison purposes. As background to this analysis, this report also provides information about the size and development of the financial market. This is based on three different indicators (the outstanding amount of debt securities issued by non‑financial corporations, stock market capitalisation and MFI credit to the domestic non-financial private sector), which, together, provide a measure of the size of financial markets.

Finally, Article 140(1) of the Treaty requires this report to take account of several other relevant factors (see Box 5). In this respect, an enhanced economic governance framework in accordance with Article 121(6) of the Treaty entered into force on 13 December 2011 with the aim of ensuring a closer coordination of economic policies and the sustained convergence of EU Member States’ economic performances. Box 5 below briefly outlines these legislative provisions and the way in which the above‑mentioned additional factors are addressed in the assessment of convergence conducted by the ECB.

Box 5 Other relevant factors

1. Treaty and other legal provisions

Article 140(1) of the Treaty requires that: “The reports of the Commission and the European Central Bank shall also take account of the results of the integration of markets, the situation and development of the balances of payments on current account and an examination of the development of unit labour costs and other price indices”.

In this respect, the ECB takes into account the legislative package on EU economic governance which entered into force on 13 December 2011. Building on the Treaty provisions under Article 121(6), the European Parliament and the EU Council adopted detailed rules for the multilateral surveillance procedure referred to in Articles 121(3) and 121(4) of the Treaty. These rules were adopted “in order to ensure closer coordination of economic policies and sustained convergence of the economic performances of the Member States” (Article 121(3)), in view of the “need to draw lessons from the first decade of functioning of the economic and monetary union and, in particular, for improved economic governance in the Union built on stronger national ownership”.[11] The legislative package includes an enhanced surveillance framework (the macroeconomic imbalance procedure or MIP) aimed at preventing excessive macroeconomic and macro‑financial imbalances by helping diverging EU Member States to establish corrective plans before divergence becomes entrenched. The MIP, with both preventive and corrective arms, applies to all EU Member States, except those which, being under an international financial assistance programme, are already subject to closer scrutiny coupled with conditionality. The MIP includes an alert mechanism for the early detection of imbalances, based on a transparent scoreboard of indicators with alert thresholds for all EU Member States, combined with economic judgement. This judgement should take into account, among other things, nominal and real convergence inside and outside the euro area.[12] When assessing macroeconomic imbalances, this procedure should take due account of their severity and their potential negative economic and financial spillover effects, which aggravate the vulnerability of the EU economy and threaten the smooth functioning of Economic and Monetary Union.[13]

2. Application of Treaty provisions

In line with past practice, the additional factors referred to in Article 140(1) of the Treaty are reviewed in Chapter 5 under the headings of the individual criteria described in Boxes 1 to 4. For completeness, in Chapter 3 the scoreboard indicators are presented for the countries covered in this report (including in relation to the alert thresholds), thereby ensuring the provision of all available information relevant to the detection of macroeconomic and macro‑financial imbalances that may be hampering the achievement of a high degree of sustainable convergence as stipulated in Article 140(1) of the Treaty. Notably, EU Member States with a derogation that are subject to an excessive imbalance procedure can hardly be considered as having achieved a high degree of sustainable convergence as stipulated in Article 140(1) of the Treaty.

2.2 Compatibility of national legislation with the Treaties

2.2.1 Introduction

Article 140(1) of the Treaty requires the ECB (and the European Commission) to report, at least once every two years or at the request of a Member State with a derogation, to the Council on the progress made by the Member States with a derogation in fulfilling their obligations regarding the achievement of economic and monetary union. These reports must include an examination of the compatibility between the national legislation of each Member State with a derogation, including the statutes of its NCB, and Articles 130 and 131 of the Treaty and the relevant Articles of the Statute. This Treaty obligation of Member States with a derogation is also referred to as ‘legal convergence’.

When assessing legal convergence, the ECB is not limited to making a formal assessment of the letter of national legislation, but may also consider whether the implementation of the relevant provisions complies with the spirit of the Treaties and the Statute. The ECB is particularly concerned about any signs of pressure being put on the decision-making bodies of any Member State’s NCB which would be inconsistent with the spirit of the Treaty as regards central bank independence. The ECB also sees the need for the smooth and continuous functioning of the NCBs’ decision-making bodies. In this respect, the relevant authorities of a Member State have, in particular, the duty to take the necessary measures to ensure the timely appointment of a successor if the position of a member of an NCB’s decision-making body becomes vacant.[14] The ECB will closely monitor any developments prior to making a positive final assessment concluding that a Member State’s national legislation is compatible with the Treaty and the Statute.

Member States with a derogation and legal convergence

Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden, whose national legislation is examined in this report, each have the status of a Member State with a derogation, i.e. they have not yet adopted the euro. Sweden was given the status of a Member State with a derogation by a decision of the Council in May 1998.[15] As far as the other Member States are concerned, Articles 4[16] and 5[17] of the Acts concerning the conditions of accession provide that each of these Member States shall participate in Economic and Monetary Union from the date of accession as a Member State with a derogation within the meaning of Article 139 of the Treaty.

This report does not cover Denmark, which is a Member State with a special status and which has not yet adopted the euro. Protocol (No 16) on certain provisions relating to Denmark, annexed to the Treaties, provides that, in view of the notice given to the Council by the Danish Government on 3 November 1993, Denmark has an exemption and that the procedure for the abrogation of the derogation will only be initiated at the request of Denmark. As Article 130 of the Treaty applies to Denmark, Danmarks Nationalbank has to fulfil the requirements of central bank independence. The EMI’s Convergence Report of 1998 concluded that this requirement had been fulfilled. There has been no assessment of Danish convergence since 1998 due to Denmark’s special status. Until such time as Denmark notifies the Council that it intends to adopt the euro, Danmarks Nationalbank does not need to be legally integrated into the Eurosystem and no Danish legislation needs to be adapted.

On 29 March 2017 the United Kingdom notified the European Council of its intention to withdraw from the EU pursuant to Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. The United Kingdom withdrew from the EU on 31 January 2020 on the basis of the arrangements set out in the Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community (hereinafter the “Withdrawal Agreement”). EU law continues to be applicable to and in the United Kingdom in accordance with the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement during a transition period that started on the day of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU and ends on 31 December 2020.[18] However, according to Protocol (No 15) on certain provisions relating to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, annexed to the Treaties, the United Kingdom is under no obligation to adopt the euro unless it notifies the Council that it intends to do so. On 30 October 1997 the United Kingdom notified the Council that it did not intend to adopt the euro on 1 January 1999 and this situation has not changed. Pursuant to this notification, certain provisions of the Treaty (including Articles 130 and 131) and of the Statute do not apply to the United Kingdom. Accordingly, there is no current legal requirement to ensure that national legislation (including the Bank of England’s statutes) is compatible with the Treaty and the Statute.

The aim of assessing legal convergence is to facilitate the Council’s decisions as to which Member States fulfil ‘their obligations regarding the achievement of economic and monetary union’ (Article 140(1) of the Treaty). In the legal domain, such conditions refer in particular to central bank independence and to the NCBs’ legal integration into the Eurosystem.

Structure of the legal assessment

The legal assessment broadly follows the framework of the previous reports of the ECB and the EMI on legal convergence.[19]

The compatibility of national legislation is considered in the light of legislation enacted before 24 March 2020.

2.2.2 Scope of adaptation

Areas of adaptation

For the purpose of identifying those areas where national legislation needs to be adapted, the following issues are examined:

- compatibility with provisions on the independence of NCBs in the Treaty (Article 130) and the Statute (Articles 7 and 14.2);

- compatibility with provisions on confidentiality (Article 37 of the Statute);

- compatibility with the prohibitions on monetary financing (Article 123 of the Treaty) and privileged access (Article 124 of the Treaty);

- compatibility with the single spelling of the euro required by EU law; and

- legal integration of the NCBs into the Eurosystem (in particular as regards Articles 12.1 and 14.3 of the Statute).

‘Compatibility’ versus ‘harmonisation’

Article 131 of the Treaty requires national legislation to be ‘compatible’ with the Treaties and the Statute; any incompatibility must therefore be removed. Neither the supremacy of the Treaties and the Statute over national legislation nor the nature of the incompatibility affects the need to comply with this obligation.

The requirement for national legislation to be ‘compatible’ does not mean that the Treaty requires ‘harmonisation’ of the NCBs’ statutes, either with each other or with the Statute. National particularities may continue to exist to the extent that they do not infringe the competence in monetary matters that is irrevocably conferred on the EU. Indeed, Article 14.4 of the Statute permits NCBs to perform functions other than those specified in the Statute, to the extent that they do not interfere with the objectives and tasks of the ESCB. Provisions authorising such additional functions in NCBs’ statutes are a clear example of circumstances in which differences may remain. Rather, the term ‘compatible’ indicates that national legislation and the NCBs’ statutes need to be adjusted to eliminate inconsistencies with the Treaties and the Statute and to ensure the necessary degree of integration of the NCBs into the ESCB. In particular, any provisions that infringe an NCB’s independence, as defined in the Treaty, and its role as an integral part of the ESCB, should be adjusted. It is therefore insufficient to rely solely on the primacy of EU law over national legislation to achieve this.

The obligation in Article 131 of the Treaty only covers incompatibility with the Treaties and the Statute. However, national legislation that is incompatible with secondary EU legislation relevant for the areas of adaptation examined in this Convergence Report should be brought into line with such secondary legislation. The primacy of EU law does not affect the obligation to adapt national legislation. This general requirement derives not only from Article 131 of the Treaty but also from the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.[20]

The Treaties and the Statute do not prescribe the manner in which national legislation should be adapted. This may be achieved by referring to the Treaties and the Statute, or by incorporating provisions thereof and referring to their provenance, or by deleting any incompatibility, or by a combination of these methods.

Furthermore, among other things as a tool for achieving and maintaining the compatibility of national legislation with the Treaties and the Statute, the ECB must be consulted by the EU institutions and by the Member States on draft legislative provisions in its fields of competence, pursuant to Articles 127(4) and 282(5) of the Treaty and Article 4 of the Statute. Council Decision 98/415/EC of 29 June 1998 on the consultation of the European Central Bank by national authorities regarding draft legislative provisions[21] expressly requires Member States to take the measures necessary to ensure compliance with this obligation.

2.2.3 Independence of NCBs

As far as central bank independence is concerned, national legislation in the Member States that joined the EU in 2004, 2007 or 2013 had to be adapted to comply with the relevant provisions of the Treaty and the Statute, and be in force on 1 May 2004, 1 January 2007 and 1 July 2013 respectively. [22] Sweden had to bring the necessary adaptations into force by the date of establishment of the ESCB on 1 June 1998.

Central bank independence

In November 1995, the EMI established a list of features of central bank independence (later described in detail in its 1998 Convergence Report) which were the basis for assessing the national legislation of the Member States at that time, in particular the NCBs’ statutes. The concept of central bank independence includes various types of independence that must be assessed separately, namely: functional, institutional, personal and financial independence. Over the past few years there has been further refinement of the analysis of these aspects of central bank independence in the opinions adopted by the ECB. These aspects are the basis for assessing the level of convergence between the national legislation of the Member States with a derogation and the Treaties and the Statute.

Functional independence

Central bank independence is not an end in itself, but is instrumental in achieving an objective that should be clearly defined and should prevail over any other objective. Functional independence requires each NCB’s primary objective to be stated in a clear and legally certain way and to be fully in line with the primary objective of price stability established by the Treaty. It is served by providing the NCBs with the necessary means and instruments for achieving this objective independently of any other authority. The Treaty’s requirement of central bank independence reflects the generally held view that the primary objective of price stability is best served by a fully independent institution with a precise definition of its mandate. Central bank independence is fully compatible with holding NCBs accountable for their decisions, which is an important aspect of enhancing confidence in their independent status. This entails transparency and dialogue with third parties.

As regards timing, the Treaty is not clear about when the NCBs of Member States with a derogation must comply with the primary objective of price stability set out in Articles 127(1) and 282(2) of the Treaty and Article 2 of the Statute. For those Member States that joined the EU after the date of the introduction of the euro in the EU, it is not clear whether this obligation should run from the date of accession or from the date of their adoption of the euro. While Article 127(1) of the Treaty does not apply to Member States with a derogation (see Article 139(2)(c) of the Treaty), Article 2 of the Statute does apply to such Member States (see Article 42.1 of the Statute). The ECB takes the view that the obligation of the NCBs to have price stability as their primary objective runs from 1 June 1998 in the case of Sweden, and from 1 May 2004, 1 January 2007 and 1 July 2013 for the Member States that joined the EU on those dates. This is based on the fact that one of the guiding principles of the EU, namely price stability (Article 119 of the Treaty), also applies to Member States with a derogation. It is also based on the Treaty objective that all Member States should strive for macroeconomic convergence, including price stability, which is the intention behind the regular reports of the ECB and the European Commission. This conclusion is also based on the underlying rationale of central bank independence, which is only justified if the overall objective of price stability has primacy.

The country assessments in this report are based on these conclusions as to the timing of the obligation of the NCBs of Member States with a derogation to have price stability as their primary objective.

Institutional independence

The principle of institutional independence is expressly referred to in Article 130 of the Treaty and Article 7 of the Statute. These two articles prohibit the NCBs and members of their decision-making bodies from seeking or taking instructions from EU institutions or bodies, from any government of a Member State or from any other body. In addition, they prohibit EU institutions, bodies, offices or agencies, and the governments of the Member States from seeking to influence those members of the NCBs’ decision-making bodies whose decisions may affect the fulfilment of the NCBs’ ESCB-related tasks. If national legislation mirrors Article 130 of the Treaty and Article 7 of the Statute, it should reflect both prohibitions and not narrow the scope of their application.[23] The recognition that central banks have such independence does not have the consequence of exempting from every rule of law and to shield them from any kind of legislation.[24]

Whether an NCB is organised as a state-owned body, a special public law body or simply a public limited company, there is a risk that influence may be exerted by the owner on its decision-making in relation to ESCB-related tasks by virtue of such ownership.[25] Such influence, whether exercised through shareholders’ rights or otherwise, may affect an NCB’s independence and should therefore be limited by law.

The legal framework for central banking needs to provide a stable and long-term basis for a central bank’s functioning. A legal framework that permits frequent changes to the institutional set-up of an NCB, thus affecting its organisational or governance stability, could adversely affect that NCB’s institutional independence.[26]

Prohibition on giving instructions

Rights of third parties to give instructions to NCBs, their decision-making bodies or their members are incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute as far as ESCB-related tasks are concerned.

Any involvement of an NCB in the application of measures to strengthen financial stability must be compatible with the Treaty, i.e. NCBs’ functions must be performed in a manner that is fully compatible with their functional, institutional, and financial independence so as to safeguard the proper performance of their tasks under the Treaty and the Statute.[27] To the extent that national legislation provides for a role of an NCB that goes beyond advisory functions and requires it to assume additional tasks, it must be ensured that these tasks will not affect the NCB’s ability to carry out its ESCB-related tasks from an operational and financial point of view.[28] Additionally, the inclusion of NCB representatives in collegiate decision-making supervisory bodies or other authorities would need to give due consideration to safeguards for the personal independence of the members of the NCB’s decision-making bodies.[29]

Prohibition on approving, suspending, annulling or deferring decisions

Rights of third parties to approve, suspend, annul or defer an NCB’s decisions are incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute as far as ESCB-related tasks are concerned.[30]

Prohibition on censoring decisions on legal grounds

A right for bodies other than independent courts to censor, on legal grounds, decisions relating to the performance of ESCB-related tasks is incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute, since the performance of these tasks may not be reassessed at the political level. A right of an NCB Governor to suspend the implementation of a decision adopted by the ESCB or by an NCB decision-making body on legal grounds and subsequently to submit it to a political body for a final decision would be equivalent to seeking instructions from third parties.

Prohibition on participation in decision-making bodies of an NCB with a right to vote

Participation by representatives of third parties in an NCB’s decision-making body with a right to vote on matters concerning the performance by the NCB of ESCB-related tasks is incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute, even if such vote is not decisive. Such participation even without the right to vote is incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute, if such participation interferes with the performance of ESCB-related tasks by that decision-making bodies or endangers compliance with the ESCB’s confidentiality regime.[31]

Prohibition on ex ante consultation relating to an NCB’s decision

An express statutory obligation for an NCB to consult third parties ex ante relating to an NCB’s decision provides third parties with a formal mechanism to influence the final decision and is therefore incompatible with the Treaty and the Statute.

However, dialogue between an NCB and third parties, even when based on statutory obligations to provide information and exchange views, is compatible with central bank independence provided that:

- this does not result in interference with the independence of the members of the NCB’s decision-making bodies;

- the special status of Governors in their capacity as members of the ECB’s decision-making bodies is fully respected; and

- confidentiality requirements resulting from the Statute are observed.[32]

Discharge provided for the duties of members of the NCB’s decision-making bodies

Statutory provisions regarding the discharge provided by third parties (e.g. governments) regarding the duties of members of the NCB’s decision-making bodies (e.g. in relation to accounts) should contain adequate safeguards, so that such a power does not impinge on the capacity of the individual NCB member independently to adopt decisions in respect of ESCB-related tasks (or implement decisions adopted at ESCB level). Inclusion of an express provision to this effect in NCB statutes is recommended.

Personal independence

The Statute’s provision on security of tenure for members of NCBs’ decision-making bodies further safeguards central bank independence. NCB Governors are members of the General Council of the ECB and will be members of the Governing Council upon adoption of the euro by their Member States. Article 14.2 of the Statute provides that NCB statutes must, in particular, provide for a minimum term of office of five years for Governors. It also protects against the arbitrary relieving Governors from office by providing that Governors may only be relieved from office if they no longer fulfil the conditions required for the performance of their duties or if they have been guilty of serious misconduct. In such cases, Article 14.2 of the Statute provides for the possibility of recourse to the Court of Justice of the European Union, which has the power to annul the national decision taken to relieve a Governor from office.[33] The suspension of a Governor may effectively amount to relieving from office for the purposes of Article 14.2 of the Statute.[34] NCB statutes must comply with this provision as set out below.

Article 130 of the Treaty prohibits national governments and any bodies from influencing the members of NCBs’ decision-making bodies in the performance of their tasks. In particular, Member States may not seek to influence the members of the NCB’s decision-making bodies by amending national legislation affecting their remuneration, which, as a matter of principle, should apply only for future appointments.[35]

Minimum term of office for Governors

In accordance with Article 14.2 of the Statute, NCB statutes must provide for a minimum term of office of five years for a Governor. This does not preclude longer terms of office, while an indefinite term of office does not require adaptation of the statutes provided the grounds for the relieving a Governor from office are in line with those of Article 14.2 of the Statute. Shorter periods cannot be justified even if only applied during a transitional period.[36] National legislation which provides for a compulsory retirement age should ensure that the retirement age does not interrupt the minimum term of office provided by Article 14.2 of the Statute, which prevails over any compulsory retirement age, if applicable to a Governor.[37] When an NCB’s statutes are amended, the amending law should safeguard the security of tenure of the Governor and of other members of decision-making bodies who are involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks.[38]

Grounds for relieving Governors from office

NCB statutes must ensure that Governors may not be dismissed for reasons other than those mentioned in Article 14.2 of the Statute. The purpose of the requirement under that Article is to prevent the authorities involved in the appointment of Governors, particularly the government or parliament, from exercising their discretion to dismiss a Governor. NCB statutes should either refer to Article 14.2 of the Statute, or incorporate its provisions and refer to their provenance, or delete any incompatibility with the grounds for relieving from office laid down in Article 14.2, or omit any mention of grounds for relieving from office (since Article 14.2 is directly applicable).[39] Once elected or appointed, Governors may not be relieved from office under conditions other than those mentioned in Article 14.2 of the Statute even if they have not yet taken up their duties. As the conditions under which a Governor may be relieved from office are autonomous concepts of Union law, their application and interpretation do not depend on national contexts.[40] Ultimately, it is for the Court of Justice of the European Union, in the context of the powers conferred on it by the second subparagraph of Article 14.2 of the Statute, to verify that a decision taken to relieve a Governor of a national central bank from office is justified by sufficient indications that they have engaged in serious misconduct capable of justifying such a measure.[41]

Security of tenure and grounds for relieving from office of members of NCBs’ decision-making bodies, other than Governors, who are involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks

Applying the same rules for the security of tenure and grounds for relieving of Governors from office to other members of the decision-making bodies of NCBs involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks will also safeguard the personal independence of those persons.[42] The provisions of Article 14.2 of the Statute are not restricted to the security of tenure of office to Governors, and Article 130 of the Treaty and Article 7 of the Statute refer to “members of the decision-making bodies” of NCBs, rather than to Governors specifically. This applies in particular where a Governor is “first among equals” with colleagues with equivalent voting rights or where such other members are involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks.

Right of judicial review

Members of the NCBs’ decision-making bodies must have the right to submit any decision to relieve them of their office to an independent court of law, in order to limit the potential for political discretion in evaluating the grounds for such a decision.

Article 14.2 of the Statute stipulates that NCB Governors who have been dismissed from office may refer such a decision to the Court of Justice of the European Union. National legislation should either refer to the Statute or remain silent on the right to refer such decision to the Court of Justice of the European Union (as Article 14.2 of the Statute is directly applicable).

National legislation should also provide for a right of review by the national courts of a decision to dismiss any other member of the decision-making bodies of the NCB involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks. This right can either be a matter of general law or can take the form of a specific provision. Even though this right may be available under the general law, for reasons of legal certainty it could be advisable to provide specifically for such a right of review.

Safeguards against conflicts of interest

Personal independence also entails ensuring that no conflict of interest arises between the duties of members of NCB decision-making bodies involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks in relation to their respective NCBs (and of Governors in relation to the ECB) and any other functions which such members of decision-making bodies may have and which may jeopardise their personal independence.[43] As a matter of principle, membership of a decision-making body involved in the performance of ESCB-related tasks is incompatible with the exercise of other functions that might create a conflict of interest. In particular, members of such decision-making bodies may not hold an office or have an interest that may influence their activities, whether through office in the executive or legislative branches of the state or in regional or local administrations, or through involvement in a business organisation. Particular care should be taken to prevent potential conflicts of interest on the part of non-executive members of decision-making bodies.

Financial independence

The overall independence of an NCB would be jeopardised if it could not autonomously avail itself of sufficient financial resources to fulfil its mandate, i.e. to perform the ESCB-related tasks required of it under the Treaty and the Statute.

Member States may not put their NCBs in a position where they have insufficient financial resources and inadequate net equity[44] to carry out their ESCB or Eurosystem-related tasks, as applicable. It should be noted that Articles 28.1 and 30.4 of the Statute provide for the possibility of the ECB making further calls on the NCBs to contribute to the ECB’s capital and to make further transfers of foreign reserves.[45] Moreover, Article 33.2 of the Statute provides[46] that, in the event of a loss incurred by the ECB which cannot be fully offset against the general reserve fund, the ECB’s Governing Council may decide to offset the remaining loss against the monetary income of the relevant financial year in proportion to and up to the amounts allocated to the NCBs. The principle of financial independence means that compliance with these provisions requires an NCB to be able to perform its functions unimpaired.

Additionally, the principle of financial independence requires an NCB to have sufficient means not only to perform its ESCB-related tasks but also its national tasks (e.g. supervision of the financial sector, financing its administration and own operations, provision of Emergency Liquidity Assistance[47]).

For all the reasons mentioned above, financial independence also implies that an NCB should always be sufficiently capitalised. In particular, any situation should be avoided whereby for a prolonged period of time an NCB’s net equity is below the level of its statutory capital or is even negative, including where losses beyond the level of capital and the reserves are carried over.[48] Any such situation may negatively impact on the NCB’s ability to perform its ESCB-related tasks but also its national tasks. Moreover, such a situation may affect the credibility of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy. Therefore, the event of an NCB’s net equity becoming less than its statutory capital or even negative would require that the respective Member State provides the NCB with an appropriate amount of capital at least up to the level of the statutory capital within a reasonable period of time so as to comply with the principle of financial independence. As concerns the ECB, the relevance of this issue has already been recognised by the Council by adopting Council Regulation (EC) No 1009/2000 of 8 May 2000 concerning capital increases of the European Central Bank.[49] It enabled the Governing Council of the ECB to decide on an actual increase of the ECB’s capital to sustain the adequacy of the capital base to support the operations of the ECB;[50] NCBs should be financially able to respond to such ECB decision.

The concept of financial independence should be assessed from the perspective of whether any third party is able to exercise either direct or indirect influence not only over an NCB’s tasks but also over its ability to fulfil its mandate, both operationally in terms of manpower, and financially in terms of appropriate financial resources. The aspects of financial independence set out below are particularly relevant in this respect.[51] These are the features of financial independence where NCBs are most vulnerable to outside influence.

Determination of budget

If a third party has the power to determine or influence an NCB’s budget, this is incompatible with financial independence unless the law provides a safeguard clause so that such a power is without prejudice to the financial means necessary for carrying out the NCB’s ESCB-related tasks.[52]

The accounting rules

The accounts should be drawn up either in accordance with general accounting rules or in accordance with rules specified by an NCB’s decision-making bodies. If, instead, such rules are specified by third parties, the rules must at least take into account what has been proposed by the NCB’s decision-making bodies.

The annual accounts should be adopted by the NCB’s decision-making bodies, assisted by independent accountants, and may be subject to ex post approval by third parties (e.g. the government or parliament). The NCB’s decision-making bodies should be able to decide on the calculation of the profits independently and professionally.

Where an NCB’s operations are subject to the control of a state audit office or similar body charged with controlling the use of public finances, the scope of the control should be clearly defined by the legal framework,[53] should be without prejudice to the activities of the NCB’s independent external auditors[54] and further, in line with the principle of institutional independence, it should comply with the prohibition on giving instructions to an NCB and its decision-making bodies and should not interfere with the NCB’s ESCB-related tasks.[55] The state audit should be done on a non-political, independent and purely professional basis.[56]

Distribution of profits, NCBs’ capital and financial provisions

With regard to profit allocation, an NCB’s statutes may prescribe how its profits are to be allocated. In the absence of such provisions, decisions on the allocation of profits should be taken by the NCB’s decision-making bodies on professional grounds, and should not be subject to the discretion of third parties unless there is an express safeguard clause stating that this is without prejudice to the financial means necessary for carrying out the NCB’s ESCB-related tasks as well as national tasks.[57]

Profits may be distributed to the State budget only after any accumulated losses from previous years have been covered[58] and financial provisions deemed necessary to safeguard the real value of the NCB’s capital and assets have been created. Temporary or ad hoc legislative measures amounting to instructions to the NCBs in relation to the distribution of their profits are not permissible.[59] Similarly, a tax on an NCB’s unrealised capital gains would also impair the principle of financial independence.[60]

A Member State may not impose reductions of capital on an NCB without the ex ante agreement of the NCB’s decision-making bodies, which must aim to ensure that it retains sufficient financial means to fulfil its mandate under Article 127(2) of the Treaty and the Statute as a member of the ESCB. For the same reason, any amendment to the profit distribution rules of an NCB should only be initiated and decided in close cooperation with the NCB, which is best placed to assess its required level of reserve capital.[61] As regards financial provisions or buffers, NCBs must be free to independently create financial provisions to safeguard the real value of their capital and assets. Member States may also not hamper NCBs from building up their reserve capital to a level which is necessary for a member of the ESCB to fulfil its tasks.[62]

Financial liability for supervisory authorities

Most Member States place their financial supervisory authorities within their NCB. This is unproblematic if such authorities are subject to the NCB’s independent decision-making. However, if the law provides for separate decision-making by such supervisory authorities, it is important to ensure that decisions adopted by them do not endanger the finances of the NCB as a whole. In such cases, national legislation should enable the NCB to have ultimate control over any decision by the supervisory authorities that could affect an NCB’s independence, in particular its financial independence.

Autonomy in staff matters

Member States may not impair an NCB’s ability to employ and retain the qualified staff necessary for the NCB to perform independently the tasks conferred on it by the Treaty and the Statute.[63] Also, an NCB may not be put into a position where it has limited control or no control over its staff, or where the government of a Member State can influence its policy on staff matters.[64] Any amendment to the legislative provisions on the remuneration for members of an NCB’s decision-making bodies and its employees should be decided in close and effective cooperation with the NCB,[65] taking due account of its views, to ensure the ongoing ability of the NCB to independently carry out its tasks.[66] Autonomy in staff matters extends to issues relating to staff pensions. Further, amendments that lead to reductions in the remuneration for an NCB's staff should not interfere with that NCB’s powers to administer its own financial resources, including the funds resulting from any reduction in salaries that it pays.[67]

Ownership and property rights

Rights of third parties to intervene or to issue instructions to an NCB in relation to the property held by an NCB are incompatible with the principle of financial independence.

2.2.4 Confidentiality

The obligation of professional secrecy for ECB and NCB staff as well as for the members of the ECB and NCB governing bodies under Article 37 of the Statute may give rise to similar provisions in NCBs’ statutes or in the Member States’ legislation. The primacy of Union law and rules adopted thereunder also means that national laws on access by third parties to documents should comply with relevant Union law provisions, including Article 37 of the Statute, and may not lead to infringements of the ESCB’s confidentiality regime. The access of a state audit office or similar body to an NCB’s confidential information and documents must be limited to what is necessary for the performance of the statutory tasks of the body that receives the information and must be without prejudice to the ESCB’s independence and the ESCB’s confidentiality regime to which the members of NCBs’ decision-making bodies and staff are subject. [68] NCBs should ensure that such bodies protect the confidentiality of information and documents disclosed at a level corresponding to that applied by the NCBs.

2.2.5 Prohibition on monetary financing and privileged access

On the monetary financing prohibition and the prohibition on privileged access, the national legislation of the Member States that joined the EU in 2004, 2007 or 2013 had to be adapted to comply with the relevant provisions of the Treaty and the Statute and be in force on 1 May 2004, 1 January 2007 and 1 July 2013 respectively. Sweden had to bring the necessary adaptations into force by 1 January 1995.

Prohibition on monetary financing

Article 123(1) of the Treaty prohibits overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the ECB or with the NCBs in favour of EU institutions, bodies, offices or agencies, central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of Member States. It also prohibits the purchase directly from these public sector entities by the ECB or NCBs of debt instruments. The Treaty contains one exemption from this monetary financing prohibition: it does not apply to publicly-owned credit institutions which, in the context of the supply of reserves by central banks, must be given the same treatment as private credit institutions (Article 123(2) of the Treaty). Moreover, the ECB and the NCBs may act as fiscal agents for the public sector bodies referred to above (Article 21.2 of the Statute). The precise scope of application of the monetary financing prohibition is further clarified by Council Regulation (EC) No 3603/93 of 13 December 1993 specifying definitions for the application of the prohibitions referred to in Articles 104 and 104b (1) of the Treaty,[69] according to which the prohibition includes any financing of the public sector’s obligations vis-à-vis third parties.