Globalisation and public perceptions

Dinner speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBat the joint meeting of the GEPA-GPA-GSPABrussels, 3 December 2007

1. Introduction [1]

Ladies and gentlemen,

It’s pleasure for me to be with you tonight to talk about a fascinating subject- globalisation, which will be one of the main topics of this conference.

In accepting this invitation a few weeks ago, and having just read Ed Leamer’s wonderful survey of The World is Flat in the Journal of Economic Literature, [2] I tried myself to fully exploit the benefits that – according to economists – globalisation offers us I sent an e-mail to Bangalore (India) asking someone to draft a dinner speech on globalisation. The following morning a well-written piece appeared in my inbox, with an invoice of little more than €100 (Bangalore seems also to have started invoicing in euros!). I was happy. After all, the time it would have taken me to write a 30 minutes speech on globalisation would certainly exceed €100! But then I asked myself if you would have been happy with such a speech. Would you invite me next time? Maybe next time you would call Bangalore directly, and perhaps even Bollywood and hire an actor to deliver the speech. My anxiety increased in such a perspective, and I started working hard on my own speech, together with my collaborators in the ECB, to try maintaining a competitive advantage. In the meantime I understood why – when your own job is at stake – the public perception of globalisation is somewhat less enthusiastic than that of economists.

I then decided to look at the issue of globalisation precisely from the perspective of the public opinion. For economists, who focus on economic overall performance, it is difficult not to be enthusiastic about globalisation: the world economy has rarely grown as strongly as in the past decade, despite several shocks. In emerging economies, hundreds of millions of people have been lifted from poverty and, most noticeably in China, a middle class is appearing. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the number of people engaged in market activities and no longer trapped in a subsistence economy has practically doubled, from 1.5 to 3 billion.

Globalisation is, however, not only an economic phenomenon. It has many facets: the socioeconomic dimension, the environmental aspect, questions of national identity, and, of course, the highly sensitive issue of migration. Nevertheless, the economic aspect of globalisation remains the most pressing one in the public opinion. I will try to look more deeply into that perspective.

I should say from the outset that these reflections will not lead me to call for a stop to globalisation. None of us wants to see a repetition of the 1930s. However, the challenge remains to minimising the costs so as to increase acceptance by our societies. I will not try to offer definite prescriptions. Instead, I will try to raise some issues that I see as problematic or still unresolved, and hope to stimulate the debate at tomorrow’s conference.

I’d like to touch upon three issues; first, public perceptions of globalisation; second, the evidence on costs and benefits of globalisation, with particular reference to the euro area; third, the opportunities and challenges raised by financial globalisation. In my conclusions, I will also elaborate on the role of Europe in this process.

2. Perceptions of globalisation

How does the public perceive globalisation? I would like to underline 4 ‘stylised facts’ that can be drawn from existing analyses. [3]

First, Europeans are more inclined than others, in particular Americans, to view globalisation with concern. Taking the EU as a whole, public opinion is evenly split between supporters and opponents of globalisation. The situation varies considerably across countries. Anxiety about globalisation is very noticeable in France (but is also high in Greece), in particular in relation to its impact on jobs. By contrast, support is high in Scandinavian countries, such as Denmark and Sweden. Second, cultural competence, i.e. the ability to interact effectively with people of different cultures and education, are inversely related to the degree of concern about globalisation. Support for globalisation is strongest among high-skilled workers in mature economies. The relative lack of support for globalisation among lower-skilled workers and the least educated could indicate that they may be uncertain about the general costs and benefits of globalisation, but see the individual costs more clearly, perhaps more rationally. Concerns about the economic costs of globalisation for certain groups in society have led to the creation of the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, an EU initiative which aims to help workers made redundant as a result of changing global trade patterns to find another job as quickly as possible. This confirms that Europeans are more inclined than others to support redistribution, which is in line with recent results in the literature indicating that Europeans are more concerned about inequality than the Americans. [4]

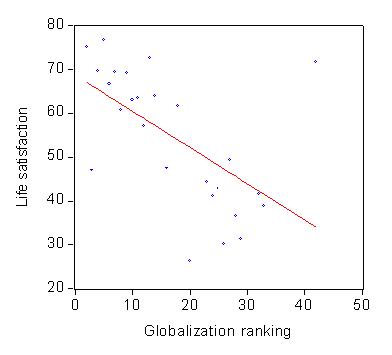

Third, there is no prima facie evidence that measures of reported happiness or ‘Life satisfaction’ are negatively affected by globalisation. Regression analysis suggests in fact a positive relationship between ‘Life satisfaction’ in OECD countries against the ranking of each OECD country in a Globalization Index (See Figure 1). [5] This might mean that globalisation makes people happier but also that happier countries tend to become more globalised. [6]

Fourth, and this an important issue to which I will turn later in my speech, EU citizens think that globalisation is influenced far more by the EU than by national governments. Indeed, it is unlikely that any European country can have, by itself, sufficient weight to influence the course of globalisation and the “rules of the game” of the global economy. Only the EU as a whole can have enough ‘punch’ to turn things in the direction that European citizens want. This creates a “demand” for more ‘Europe’ in the globalisation process, to which Europe does not seem to be responding. I will come back to this later.

In my opinion, policy-makers (including central banks) have to take these perceptions seriously. In economics, perceptions shape reality. It’s therefore important to understand how globalisation affects the behaviour of households and firms.

Let me refer to an example provided by Robert Shiller. [7] Suppose that a young person is uncertain whether to pursue a career in which she has real talent but which is fraught with risks- say, as a molecular biologist - or a less risky career, with lower value added. A highly uncertain economic environment, with rapid technological progress and the looming prospect of offshoring, increases risks. If such risks are perceived as falling entirely on the shoulders of individuals, a worse equilibrium may be reached, where by high value-added jobs that require long-term investment, such as molecular biologist, are shunned while jobs less threatened by off-shoring (say, hairdresser or restaurant owner) are in greater demand. [8] The hypothesis is therefore that economic uncertainty and higher competition may have an adverse effect on jobs that require long-term investment. This may lead to under-investment in society. This hypothesis has to be fully tested.

I raised this issue with Ned Phelps a few days ago, as we met at a conference. He looked at me a bit puzzled and said: “It sounds like a very European way of thinking!”. I guess I should turn the issue back to you.

Mobility is another issue that raises concerns in our societies. In the global economy, being mobile definitely provides a competitive edge. In the European Union, only a tiny fraction of workers live in another EU country, because of the many obstacles to mobility, not least the portability of the pension regime.

Another issue that is present in the public mind is the share of wages and profits in total income, which shifted in favour of profits over the past decade. [9] As a result, globalisation might be seen by the public as benefiting the corporate world (and their top managers).

Again, these are issues that policy-makers, including central bankers, have to recognise and take seriously. We need to acknowledge, in particular, that globalisation produces both winners and losers, at least temporarily. Moreover, as I will argue, even winning in absolute terms but losing in relative terms might be an issue, and create a powerful backlash against globalisation. An efficient system to protect individuals from the negative fallout of globalisation and encourage them to be entrepreneurial and risk-taking is therefore essential.

Let me now turn to the economics of globalisation and, in particular, to the existing empirical evidence.

3. Globalisation, technological innovation and income distribution: the evidence

In the euro area, globalisation has clearly stimulated external trade as well as the flows and stocks of its foreign assets and liabilities. Trade openness has increased markedly over time, especially since the early 1990s, and is growing more rapidly than that of either the US or Japan.

Globalisation has certainly been a major driver of the strong growth of extra-euro area imports, with outsourcing to low-cost countries and the internationalisation of production playing an important role. Over the past six years, the share accounted for by low-cost countries in extra-euro area manufacturing imports has increased from just over one-third to almost a half. Among those countries, China and the EU’s new Member States have been the main contributors, with their shares roughly doubling since the mid-1990s. Those developments have contributed dampening euro area manufacturing import prices by about 2 percentage points between 1996 and 2004. Despite the significant upward pressure of globalisation on oil and other commodity prices, there is evidence that the joint effect of all the various globalisation-related impacts on prices has been mildly disinflationary so far.

At the same time, some of the efforts of globalisation – particularly the labour market – are causing concerns. For instance, as competition from low-wage countries increases, the bargaining power of domestic workers and unions may have somewhat weakened, as a result of fears of a potential relocation of production abroad. This may have fostered wage moderation in industrial economies and partly explain the rise in inequality in many developed countries.

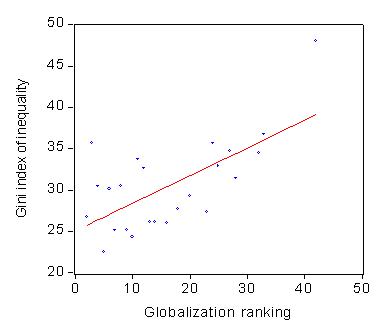

Labour market adjustment to globalisation seems to be occurring mainly via a reduction in the relative wages of the lower-skilled in the flexible labour markets of the US and the UK, and via a reduction in low-skill employment in the more rigid labour markets of continental Europe. Between 1990 and the early 2000s, some measures of income inequality, such as the Gini coefficient, have indeed increased, though the picture varies substantially from country to country and does not appear to be a generalised phenomenon (with an increase in the UK, China and the US, no change in India, and falling inequality in France and Brazil). [10] However, the finding of a generalised increased in income inequality in the last decade is not uncontroversial in the literature. In any event, the simple bivariate cross-country evidence, at least among OECD countries (see Figure 2), suggests that the more globalised countries have less, not more, income inequality. Again, I should stress that this is just prima facie evidence. I am not sure that these correlations survive in a multivariate setting and when subjected to rigorous econometric tests.

An important issue to consider is that it is quite difficult to disentangle the effects of globalisation and outsourcing from other factors, such as the impact of skill-biased technological change. Indeed, most of the empirical work suggests that the main reason for the decline in demand for less-skilled labour in advanced countries is due to technology rather than to trade-related impacts of globalisation. Nonetheless, while globalisation and technological progress go hand in hand, for the public at large, globalisation is an easier concept to grasp and to criticize.

Concerns about a link between globalisation and income inequality can explain two stylised facts in the public’s perception of globalisation. First, it can explain why globalisation is viewed sceptically in advanced economies, especially by the less well-off. In fact, there is substantial empirical evidence indicating that in developed countries people pay more attention to relative income, as much as and possibly more so than absolute income. [11] Those who lose out from globalisation in relative terms may resent it, even when they gain in absolute terms. Second, it explains why support for globalisation is higher in developing countries, where arguably concern for absolute (rather than relative) income is larger (since income is just above, and in some cases still below, the subsistence level).

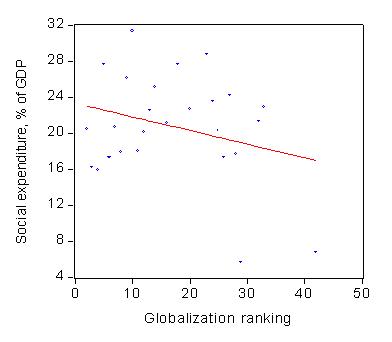

Globalisation has raised concerns on the possibility that it might trigger a “race to the bottom” between countries and puts pressure on governments to reduce job protection, welfare benefits and social insurance. At the same time, there a re also concerns that globalisation and liberalisation of trade and factor mobility may also erode the tax bases. Much of the empirical work finds no strong evidence of globalisation-induced changes in either the level or composition of public-spending. [12] There is evidence, if anything, of a slightly positive relationship between social expenditure as a share of GDP and the degree of Globalization across OECD countries (See Figure 3). Scandinavian countries, for example, are in the top league of all measures of globalisation but are also characterised by very high social spending (though this “model” has recently been under some pressure).

In spite of this evidence, the issue of labours getting its fair share of the gains of globalisation is on the table of political discussions. Restoring the purchasing power of low wages, affected in particular by the recent increases in oil and food prices – which are to some extent also a by-product of globalisation – is a pressing political issue in several countries.

Economists have to take these discussions and debates into account and influence them appropriately, so as to avoid taking wrong decisions. Indeed, there are good and bad ways to support the income of those who are more directly exposed to the impact of globalisation. The bad - unsustainable – way is to consider wage income as and exogenous “independent” variable, as was the case for instance in Italy in the mid-seventies. This approach might lead to support the income of some individuals but also to an increase in inflation and to a generalised loss of employment. Keeping inflation under control, under current circumstances remains a priority for monetary policy. Suggesting that inflation is not a problem and that monetary policy should care for growth rather than for inflation will not help. It will only lead to a loss of credibility because for the public inflation is, indeed, a problem. The lessons from monetary policy over the last 30 years should not be forgotten.

The good way to increase disposable income is to act on the variables that affect it in a structural manner. The following avenues can be considered.

First, deregulate and increase competition in the non –traded sectors, so as to reduce prices of goods and services not open to competition. Europe – especially continental Europe – has a lot to do in this area. This may mean, in some instances, renouncing to “historical champions”. One should realize that having national champions in some areas comes at a cost for the public at large, in terms of higher prices.

Second, reduce public expenditure, so that tax cuts for low-income people can be sustained over time without jeopardising fiscal sustainability.

Third, link wage increases to productivity, especially at the firm level, so as to create the incentives, for all managers and workers, to increase and monitor productivity. This is still not the case in several euro area countries.

Last but not least, although it is more of a long-term goal, increase investment in human capital, an objective we all share but for which academics certainly have a particular responsibility.

4. Financial globalisation

Let me also touch briefly on financial globalisation. One of the most impressive aspects of globalisation is the spectacular rise in cross-border financial flows. Between the mid-1980s and 2004, the sum of mature economies’ foreign assets and liabilities as a share of GDP grew threefold. In theory, this should have resulted in an improvement in the global allocation of capital, enhancing risk sharing across countries and consumption smoothing. As you know, not all of the financial globalisation has worked in the textbook way. While FDI flows are generally in the right direction, that is “downhill” (from developed, capital-rich countries to emerging, capital-poor countries), it is not the case for portfolio flows, that tend to move “uphill”. This has created a rather paradoxical situation, in which the world’s richest economy maintains a large current account deficit, largely financed by poor countries.

Research has revealed that not all countries benefit in the same way from financial globalisation; in order to fully reap its benefits, a country must have strong institutions, in particular a sound legal and supervisory system. [13] This is all the more so as financial globalisation is inevitably associated with financial innovation, to the point that the two phenomena overlap and become hard to distinguish. The rising importance of certain non-bank intermediaries, such as hedge funds and private equity, and new financial instruments, such as structured products, has taken place on a global scale. Moreover, financial globalisation makes individual financial markets and systems more vulnerable to cross-border contagion, and we have a sobering reminder of this in the current market turmoil.

The combination of globalisation and innovation in finance has contributed to a growing asymmetry of information in capital markets. [14] This is particularly the case for structured products, which often originate in one country, are repackaged in another, and sold in a third. It is fair to say that not only retail investors, but also bank and financial managers do not always have the necessary financial education, the resources and the time to understand all the risks inherent in these types of product.

Asymmetric information entails two types of risk. The first risk is that the informed party takes advantage of its information lead at the expense of the less informed. This has obvious implications in terms of income and wealth (re-)distribution from the less informed party (the retail investor) to the more informed one (financial industry managers), a risk that is certainly heightened by the complexity of the financial products in question. The second risk is that, once this redistribution occurs, a strong backlash is created, with the public turning against financial globalisation.

Financial turmoil, such as the one we are currently experiencing, expose financial globalisation to criticism. In particular, some observers criticize the fact that policies are implemented to support the financial system in the face of the current turmoil, while similar policies are denied to other sectors when facing similarly critical moments. The reason for such a support is that the financial sector is special, precisely because of the asymmetric nature of the information it processes and requires regulation and supervision. This reasoning, however, is based on two principles. First, supervisory authorities should be able to distinguish between sound and unsound institutions, so that only the former are supported in case of turmoil. Second, the unsound institutions, and in particular the managers responsible for unsound decisions, should bear responsibility for their own mistakes and should not be bailed out.

One can question whether these two basic principles are being fully respected in the current turmoil. Indeed, it has proven very difficult for supervisory authorities to appropriately assess the soundness of institutions. Authorities have basically relied on the self-assessment of financial institutions balance sheets and their publicly disclosed accounts, without the possibility of really questioning them. In fact, financial institutions themselves seem to have had, at some point, little knowledge about their own situation, and the assumptions underlying their own disclosures have not always been fully transparent. Market participants are evidently still full of doubts about the soundness of their counterparties, as reflected in the current large credit spreads in the money market. It appears that supervisory authorities may not have much more information than those available to other market participants to assess the creditworthiness of major institutions.

Furthermore, those responsible for wrong investment decisions do not seem so far to having been substantially penalised, in a way that will discourage similar behaviour in the future. Several top managers have stepped down from their positions with huge payment compensation. Broader responsibilities for internal risk management and control, in particular within financial institutions’ boards, do not seem to having been fully scrutinised yet. It might be too early to judge, but one of the causes of the recent turmoil has certainly been poor internal governance. Unless this issue is properly addressed going forward, the risk of creating moral hazard cannot be underestimated. Furthermore, it would be difficult for the public at large to accept that those who will suffer most from this phase of turbulence will be those that put their trust in financial institutions’ advice, while those that provided the advice and made the investment mistakes could walk away with only their bonuses affected. This could validate the concerns, that already exist, about the effects of financial globalisation on the concentration of financial wealth worldwide, which is of one order of magnitude more unequal compared with income. [15]

A final lesson from the current turmoil is that the complexities of finance in a globalised world call for more financial education, especially for the poorer members of society. The degree of financial literacy of the population, according to the evidence, raises concern as to people’s ability to reap the benefits of globalisation. These are matters which central banks and other policy-making authorities should have a keen interest in pursuing.

To sum up, the recent financial turmoil is not likely to make financial globalisation more popular. Unless policy authorities, starting from those in charge of financial supervision, draw the appropriate lessons and have the courage to recognise what went wrong and how their task can be improved, they risk loosing the confidence of citizens, and ultimately their independence. In Europe, a reflection is needed on how far the current Lamfalussy framework can be pushed to accommodate strengthened cooperation between national supervisory authorities and on whether some institutional change is required.

5. What can Europe do?

To summarise, policy-makers and economists should acknowledge the negative perceptions of the European public opinion towards globalisation. In addition to uttering the “globalisation-is-good-for-you” mantra, policy-makers should be aware of the painful adjustment costs for those workers and firms confronted with increasing global competition. Policy-makers need to ensure that the necessary policy steps are taken to help those individuals and groups adjust efficiently to the new circumstances.

What is the role for Europe in all this? As I said, European citizens are aware that the challenges of globalisation can hardly be tackled at the local level. There thus seems to be an important role to be played by European institutions in the governance of globalisation. So why is this not happening?

There may be two - related - reasons.

The first is that for Europe to be more effective at the global level, it has to act in a united way. Such unity requires that actions conducted at the national level are more coordinated or even replaced by a European actor. The creation, or strengthening, of a European actor is objected, in many areas, by the national policy makers. “ Turkeys don’t vote for Christmas” is a dictum that would apply well to the case. Over the last few years national political or technocratic players have developed a resistance to the continuous strengthening of the European policy role and increasingly defended their national prerogatives, opposing further devolution of power to the European level. The argument - which is related to the second reason why Europe is not more present on the world scene - is that such a devolution is not supported by the people of Europe. The argument does not take into account that no occasion seems to be lost by national policy makers to blame Europe, or the euro, for any problem, including those that arise from domestic policy failures. The blame-Europe game has become a favourite sport in some capitals.

No wonder – and this is the second reason – that Europe, and its institutions, are seen as too distant by the people of Europe. Europe is not seen as addressing and solving the problems that globalisation is posing to its citizens. This is largely due to the fact that some of the tools to address globalisation and its effects are not in the hands of Europe but rather in the national policymakers’ hands. Structural policies, affecting education, welfare, research and development, labour markets, are largely within national policies. The Lisbon agenda only sets benchmarks and best practices, but it’s up to the countries to implement the policies. Other tools, related to world trade and global finance are instead in Europe’s hands which still need to be firmed.

There seems to be a vicious circle. European citizens fear globalisation and want that the latter is governed so that the poorest and more fragile are helped in the process of adaptation to a global economy. EU countries individually can hardly be global players and interact with the other big ones, such as the US, China, India and the Emerging world. A stronger, more united, Europe would be required. The Member States are not allowing this to happen. On the one side they do not want to deprive themselves with their remaining - largely illusory – powers. On the other side, they tend to blame Europe for not being able to solve the problems raised by globalisation. Europe thus seems powerless in the view of its citizens, who blame it for being so weak.

What’s the way out? A stronger Europe and at the same time a Europe closer to its citizens: this is what seems to be missing. It’s ultimately an issue of leadership. Only leaders can have the vision of providing Europe with the necessary powers and at the same time being closer to the needs of the citizens. Here’s another catch. The Leaders of Europe are chosen not by the people of Europe, but by national representatives. So long as the national representatives fear being overshadowed by a European leadership we will have no European leaders. European citizens will thus to continue fearing globalisation, much more than others around the world.

Thank you for your attention.

References

Alesina, A., R. DiTella and R. MacCulloch (2004): “Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different?”, Journal of Public Economics, 88, pp. 2009-2042.

Anderton, R., Brenton, P. and Whalley. J. (2006) Globalisation and the Labour Market: Trade, Technology and Less-Skilled Workers in Europe and the United States (2006: Routledge, London) edited by Robert Anderton, Paul Brenton and John Whalley.

Bertola, G. (2007), “Economic integration, growth, distribution: does the euro make a difference”, paper presented at the 2007 DG-ECFIN Annual Research Conference on “Growth and income distribution in an integrated Europe: does EMU make a difference?”, Brussels, 11-12 October 2007.

Bjornskov, C., Dreher, A. and J. A. V. Fischer (2007): „The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world”, Public Choice, 130, pp. 267-292.

Clark, A., Frijters, P. and M. A. Shields (2007): “Relative income, happiness and utility: an explanation of the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2840.

Chicago Council on Foreign Affairs (2006), “Public opinion survey reports”, http://www.ccfr.org/.

Davies, J. B., Sandstrom, S., Shorrocks, A. and E. N. Wolff (2006): “The World Distribution of Household Wealth”, working paper.

di Mauro, F. and Anderton, R. (2007), “The External Dimension of the Euro Area: Assessing the Linkages”, Cambridge University Press, London.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J. and Urspring, H. (2006), “The impact of globalisation on the composition of government expenditures: evidence from panel data”. Swiss Institute for Business Cycle Research, Working Paper no. 141.

Ellis, L. and K. Smith (2007): “The global upward trend in the profit share”, BIS Working Paper No. 231.

Eurobarometer 66 (2007), http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/standard_en.htm.

IMF (2007), “Globalisation and inequality”, World Economic Outlook, September 2007, Washington DC.

Kose, A., E. Prasad, K. Rogoff, and S.-J. Wie (2006b),”Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal”, NBER Working Paper 12484.

Leamer, E. E. (2007): “A flat world, a level playing field, a small world after all, or none of the above? A review of Thomas Friedman’s The World is Flat”, Journal of Economic Literature, 45, 1, pp. 83-126.

Mukoyama, T. and A. Sahin (2004): “Repeated moral hazard with persistence”, Economic Theory

Scheve, Kenneth and Matthew Slaughter (2006), “Public opinion, international economic integration, and the welfare state.” In Samuel Bowles, Pranab Bardhan, and Michael Wallerstein (eds.), Globalization and Egalitarian Redistribution, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schulze, G. and Urspring, H. (1999), “Globalisation of the economy and the nation state”, The World Economy 22, 295-352.

Shiller, R. (2003): The New Financial Order: Risk in the 21st Century, Princeton University Press.

WorldPublicOpinion and The Chicago Council on Global Affairs (2007), “World public favours globalization and trade but wants to protect environment and jobs”, http://www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/articles/btglobalizationtradera/.

Figure 1. Globalisation ranking and life satisfaction across OECD countries

Data refer to the mid 2000s. Data on Life Satisfaction from the World Values Survey, fourth wave. The globalization ranking is the ranking of countries in the A.T. Kearney/FOREIGN POLICY Globalization Index.

Figure 2. Globalisation ranking and Gini coefficient of income inequality across OECD countries

Data refer to the mid-2000s. The globalization ranking is the ranking of countries in the A.T. Kearney/FOREIGN POLICY Globalization Index. The Gini coefficient data are OECD.

Figure 3. Globalization ranking and social expenditure as a share of GDP across OECD countries

Data refer to the mid-2000s. The globalization ranking is the ranking of countries in the A.T. Kearney/FOREIGN POLICY Globalization Index. Data on social expenditure are OECD.

-

[1] The views expressed reflect only those of the author. I thank R. Anderton and L. Stracca for input and comments as well as A. Mehl and R. Straub for providing background analysis.

-

[2] See Leamer (2007).

-

[3] I draw here from a range of opinion polls, including Eurobarometer (2007), CCFR (2006) and WorldPublicOpinion & CCFR (2007). Note that the methodology across opinion is not necessarily directly comparable.

-

[4] See Alesina, Di Tella and MacCulloch (2004). They show that concern for inequality is high among the poor and the leftist in Europe, while it is restricted to rich leftists in the United States.

-

[5] This is the A.T. Kearney/FOREIGN POLICY Globalization Index, which tracks and assesses changes in four key components of global integration, incorporating measures such as trade and investment flows, movement of people across borders, volumes of international telephone traffic, Internet usage, and participation in international organizations. The data used refer to 2006.

-

[6] There is also evidence in the literature that trade openness positively contributes to Life Satisfaction; see Bjornskov, Dreher and Fischer (2007).

-

[7] See Shiller (2003).

-

[8] See Mukoyama and Sahin 2004) for similar considerations in an agency context.

-

[9] On the global nature of the rise in the profit share see Ellis and Smith (2007).

-

[10] For a recent survey of these trends, see IMF (2007).

-

[11] See, e.g. Clark et al. (2007).

-

[12] See, e.g., Dreher, Sturm and Urspring (2006).

-

[13] See Kose, Prasad, Rogoff, and Wie (2006).

-

[14] Of course, financial globalisation and innovation have also contributed to create new safe assets, notably for savers in emerging economies, thereby alleviating asymmetric information.

-

[15] See Davies et al. (2006).

Europäische Zentralbank

Generaldirektion Kommunikation

- Sonnemannstraße 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Deutschland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Nachdruck nur mit Quellenangabe gestattet.

Ansprechpartner für Medienvertreter