Overview

The euro area economy is recovering swiftly despite continued uncertainty related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and supply bottlenecks.[1] It rebounded more strongly than expected in the second quarter of 2021 and should continue to grow rapidly during the second half of the year, with real GDP exceeding its pre-crisis level by the end of 2021. Growth is subsequently expected to remain strong but to gradually normalise. This outlook is based on several assumptions: a rapid relaxation of containment measures during the second half of 2021, a gradual dissipation of supply bottlenecks as of early 2022, substantial ongoing policy support (including favourable financing conditions) and a continued global recovery. Domestic demand should remain the key driver of the recovery, also benefiting from the expected rebound in real disposable income and a reduction in uncertainty. In addition, private consumption and residential investment are likely to be supported by the large stock of accumulated savings. Real GDP is expected to grow by 5% this year, and to moderate to 4.6% and 2.1% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. Compared with the June 2021 Eurosystem staff projections, the projection for quarterly growth during the second half of 2021 has been downgraded slightly on the back of more persistent than expected supply bottlenecks, the more infectious Delta variant of the coronavirus, and the stronger data outturns for the first half of the year reducing the scope for stronger growth thereafter. This notwithstanding, for 2021 as a whole, the projection for real GDP growth has been revised up by 0.4 percentage points. The projections for 2022 and 2023 are broadly unchanged.

The inflation outlook remains characterised by a hump in 2021 followed by more moderate rates in 2022 and 2023. Inflation is expected to average 2.2% in 2021, driven by temporary upward factors. These include: a rebound in energy inflation amid strong base effects; strong increases in input costs related to supply disruptions; one-off increases in services prices as COVID-19-related restrictions ease; and the reversal of the German VAT rate cut. As these factors fade from the beginning of 2022 and temporary imbalances between supply and demand ease, HICP inflation is expected to decline to rates of 1.7% and 1.5% in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Looking through these mostly temporary factors, HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to strengthen gradually as the recovery progresses, economic slack declines, and recent commodity price increases, including oil, gradually pass through to consumer prices. Food prices are also projected to accelerate. These upward effects on headline inflation are broadly counterbalanced over the projection horizon by a slower rise in energy prices, which is shaped by the technical assumptions for oil prices. Compared with the June 2021 projections, both headline and underlying inflation have been revised upwards across the whole projection horizon. The reasons for these revisions are: recent data surprises; some more persistent upward pressures from supply disruptions; the improved demand outlook; upward effects from higher oil and non-oil commodity prices; as well as the recent depreciation of the euro exchange rate.

Growth and inflation projections for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Notes: Real GDP figures refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

1 Real economy

Real GDP rose by 2.2% in the second quarter of 2021[2], 0.8 percentage points above the figure expected in the June 2021 projections. The rebound was driven primarily by domestic demand, and notably private consumption, on account of a pick-up in real disposable income and a substantial decline in the savings rate. While the stringency of containment measures was only slightly lower than in the first quarter and broadly in line with what had been assumed in the June projections, the upward surprise in activity seems to have reflected a lower sensitivity of economic activity to COVID-19 restrictions. The level of real GDP in the second quarter was still 2½% below its level in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Chart 1

Euro area real GDP growth

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, seasonally and working day-adjusted quarterly data)

Notes: Data are seasonally and working day-adjusted. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. This chart does not show ranges around the projections. This reflects the fact that the standard computation of the ranges (based on historical projection errors) would not capture the elevated uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, alternative scenarios based on different assumptions regarding the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the associated containment measures and the degree of economic scarring are provided in Box 4.

Real GDP growth is expected to increase again vigorously in the third quarter, amid a further loosening of containment measures and strong economic sentiment indicators (Chart 1). Containment measures are assumed to be eased further in the third and fourth quarters of the year. However, these measures are expected to be somewhat stricter than assumed in the June 2021 projections, given the emergence of the Delta variant of COVID-19 and the renewed increase in new cases in July and August. Despite some easing, sentiment indicators remain at high levels, suggesting that the remaining containment measures will not result in significant disturbances to the economy. Therefore, real GDP growth is expected to remain strong in the second half of 2021 despite being revised down slightly compared with the June projections. This reflects containment measures being more stringent and supply bottlenecks more persistent than previously assumed, together with the assessment that the positive data surprises in the first half of the year reduce the scope for an additional strong rebound in the second half of the year.

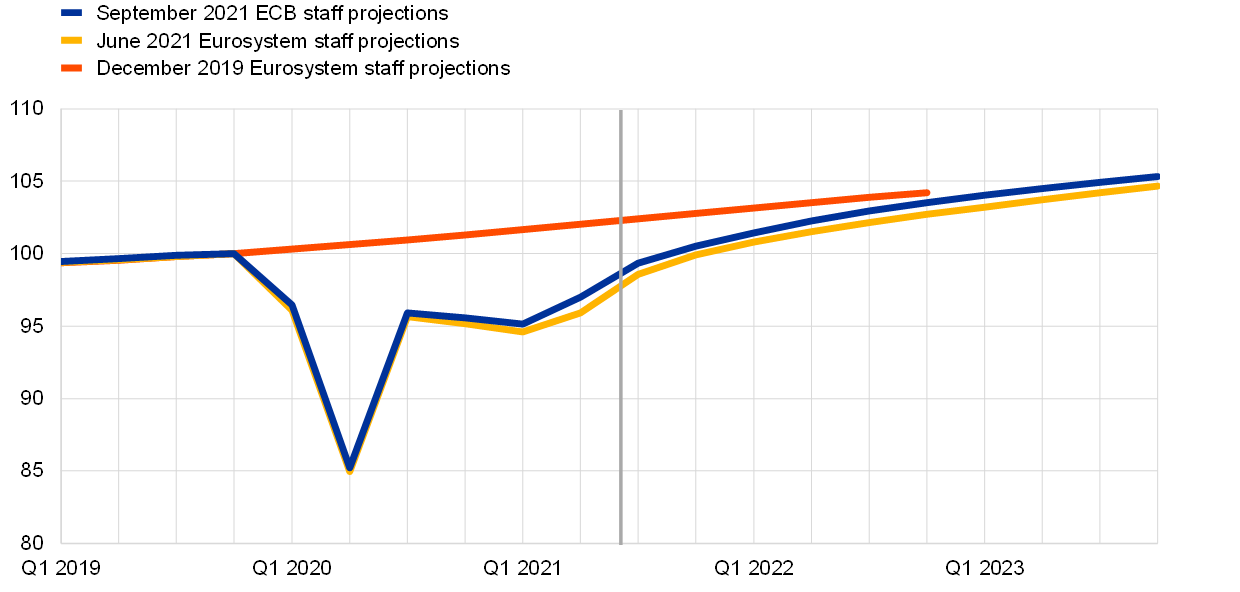

Real GDP growth is projected to remain strong in 2022 before slowing down in 2023 to a more normal rate. The projected GDP path is based on a number of assumptions. These include a full relaxation of containment measures by early 2022, a further decline in uncertainty, strong confidence in the wake of the gradual resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ongoing global recovery (Box 2). Moreover, the current supply disruptions are assumed to gradually dissipate as of early 2022. In addition, the Next Generation EU (NGEU) is expected to boost investment in some countries. More generally, fiscal, supervisory and monetary policies are assumed to remain very supportive, thereby avoiding strong adverse real-financial feedback loops. Overall, real GDP is projected to exceed its pre-crisis level in the fourth quarter of 2021 (Chart 2), one quarter earlier than in the June 2021 staff projections and, by the end of 2022, to reach a level only somewhat below that expected before the pandemic.

Chart 2

Euro area real GDP

(chain-linked volumes, 2019Q4 = 100)

Notes: Data are seasonally and working day-adjusted. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. The vertical line indicates the start of the September 2021 projection horizon.

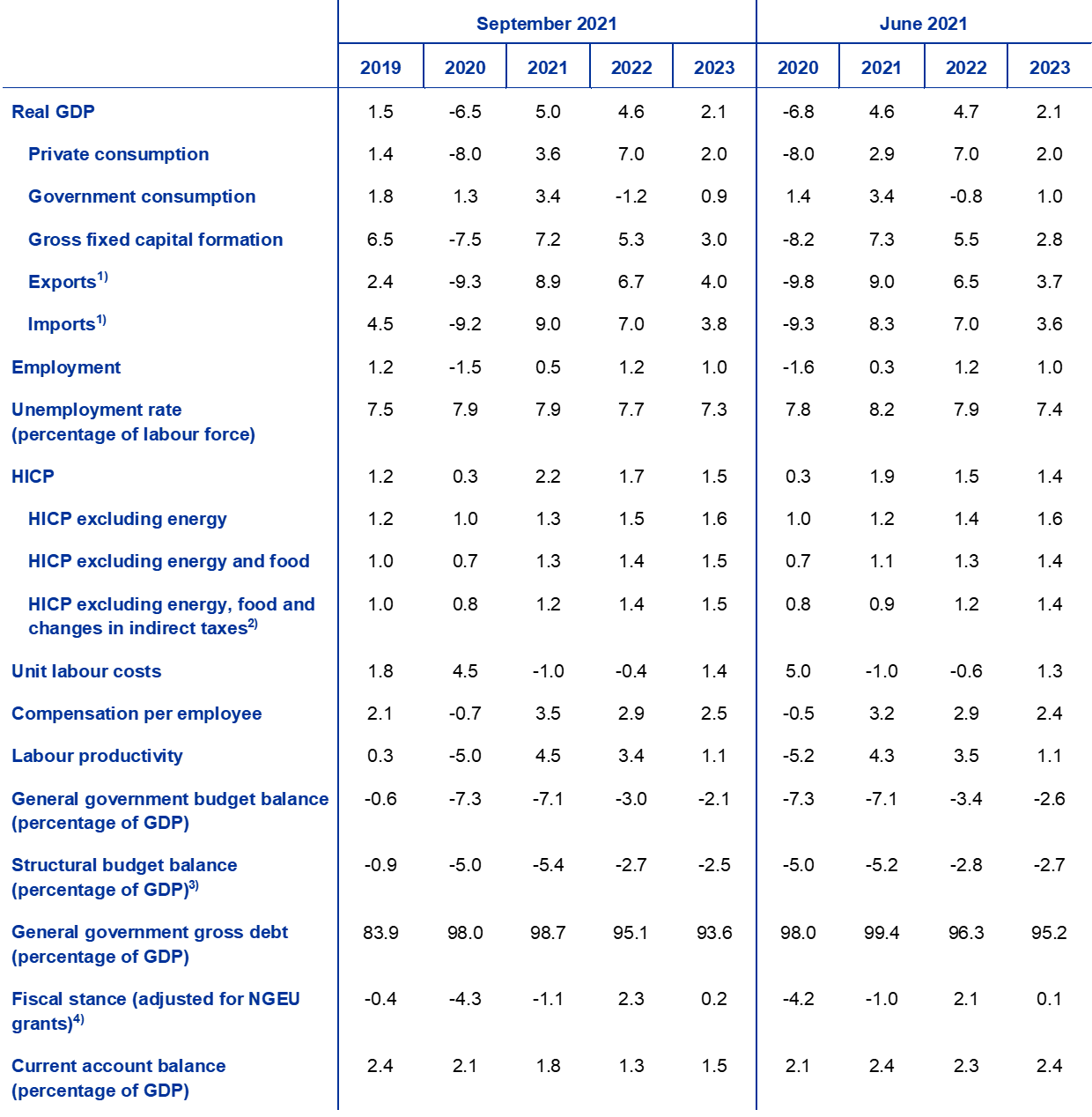

Table 1

Macroeconomic projections for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Notes: Real GDP and components, unit labour costs, compensation per employee and labour productivity refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. This table does not show ranges around the projections. This reflects the fact that the standard computation of the ranges (based on historical projection errors) would not capture the elevated uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, alternative scenarios based on different assumptions regarding the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the associated containment measures and the degree of economic scarring are provided in Box 4.

1) This includes intra-euro area trade.

2) The sub-index is based on estimates of actual impacts of indirect taxes. This may differ from Eurostat data, which assume a full and immediate pass-through of indirect tax impacts to the HICP.

3) Calculated as the government balance net of transitory effects of the economic cycle and measures classified under the European System of Central Banks definition as temporary.

4) The fiscal policy stance is measured as the change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance net of government support to the financial sector. The figures shown are also adjusted for expected NGEU grants on the revenue side.

As the key driver of the recovery, private consumption is expected to grow strongly over the projection horizon, exceeding its pre-crisis level by the first quarter of 2022. Private consumption recovered much more strongly than previously expected in the second quarter of 2021, but still stood around 6% below its pre-pandemic level. The upward surprise is likely to reflect both a stronger decline in the savings rate and stronger real income growth. Income remained mostly driven by labour income, which typically entails a relatively higher marginal propensity to consume. Private consumption is expected to continue growing strongly in the second half of the year. This is linked to containment measures being eased and also the large stock of accumulated savings which allows for the release of some pent-up demand. In the medium term, private consumption growth is projected to continue to outstrip the lower path of real income growth as the expected dissipation of uncertainty will allow for a further unwinding of excess savings.

Higher wage income is expected to support real disposable income throughout the projection horizon. As the economy continues to reopen and employment growth strengthens, wage income is expected to provide a strong contribution to real disposable income. In contrast net fiscal transfers, following their strong positive contribution in 2020, will weigh on income growth as of 2021. This reflects the expected expiry of COVID-19 support measures. Moreover, real disposable income is projected to be dampened by the projected increase in consumer price inflation.

The household saving ratio is expected to drop below its pre-crisis level in 2022, as the services sector reopens and the motives for precautionary savings lose importance. The saving rate is expected to fall substantially over the next couple of quarters as the proportion of forced savings dwindles linked to the assumed relaxation of containment measures. In addition, precautionary savings are expected to dissipate as uncertainty recedes and labour markets improve. The saving ratio should drop below its pre-crisis level in 2022 and then continue to decline slightly. It is foreseen to marginally undershoot the level expected in the pre-pandemic baseline, resulting in some unwinding of previously accumulated excess household savings. This would support a vigorous rebound in consumption. The role that accumulated savings is expected to play in the recovery of consumption is, however, somewhat reduced due to the concentration of savings in wealthier and older households with a lower propensity to consume.[3]

Box 1

Technical assumptions about interest rates, commodity prices and exchange rates

Compared with the June 2021 projections, the technical assumptions include lower interest rates, higher oil prices and a depreciation of the euro. The technical assumptions about interest rates and commodity prices are based on market expectations with a cut-off date of 16 August 2021. Short-term interest rates refer to the three-month EURIBOR, with market expectations derived from futures rates. The methodology gives an average level for these short-term interest rates of -0.5% in all years of the projection horizon. The market expectations for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields imply an average annual level of 0.0% for 2021 and 2022 and 0.1% for 2023.[4] Compared with the June 2021 projections, market expectations for short-term interest rates have marginally decreased for 2023, while market expectations for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields have decreased by around 20 basis points for 2021 and 50-60 basis points for 2022-23.

As regards commodity prices, the projections consider the path implied by futures markets by taking the average for the two-week period ending on the cut-off date of 16 August 2021. On this basis, the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil is assumed to rise from USD 42.3 in 2020 to USD 67.8 in 2021, before declining to USD 64.1 by 2023. This path implies that, in comparison with the June 2021 projections, oil prices in US dollars are around 3% to 4% higher for 2021-23. The prices of non-energy commodities in US dollars are assumed to rise strongly in 2021 and more moderately in 2022, and to slightly decrease in 2023.

Bilateral exchange rates are assumed to remain unchanged over the projection horizon at the average levels prevailing in the two-week period ending on the cut-off date of 16 August 2021. This implies an average exchange rate of USD 1.18 per euro over the period 2022-23, which is around 3% lower than in the June 2021 projections. The assumption for the effective exchange rate of the euro implies a depreciation of 1.5% since the June 2021 projections.

Technical assumptions

The recovery in housing investment is expected to lose steam during the projection horizon. Housing investment is estimated to have increased modestly in the second quarter of 2021, having already reached its pre-pandemic level in the first quarter. In the short term, positive Tobin’s Q effects, a recovery in disposable income, improved consumer confidence and the high level of accumulated savings should all support housing investment during the second half of 2021, despite some headwinds due to a further tightening of supply constraints. Housing investment momentum should gradually normalise over the remainder of the projection horizon.

Business investment is expected to remain resilient and to recover substantially over the projection horizon. Business investment continued to climb back to its pre-crisis level during the first half of 2021, benefiting from the recovery in demand, favourable financing conditions and positive Tobin’s Q effects. The rebound is expected to accelerate in the second half of 2021 as global and domestic demand recover and profit growth improves, also supported by favourable financing conditions and the positive impact of the NGEU programme. Business investment is also expected to receive a boost throughout the projection horizon from investment related to digitalisation, as well as the low carbon transition (including in the car industry, due to environmental regulations and the transition to electric vehicle production). Altogether, business investment is projected to return to its pre-pandemic level by the end of 2021.

Box 2

The international environment

Global activity is expected to regain momentum in the second half of 2021. This follows a period of moderate growth in the first half of this year, when the world economy was on a weaker footing. First, a resurgence in new infections across advanced economies led their governments to tighten containment measures in early 2021. Subsequently, the pandemic situation worsened significantly in some key emerging market economies (EMEs), weighing on global activity. As the global epidemiological situation has improved since then, containment measures have eased and mobility has risen. As a result of this, global growth is expected to increase. This is confirmed by survey data, which point to strong momentum led by advanced economies.

The projected increase in global growth remains fragile as it takes place against the backdrop of persistent supply bottlenecks and the spread of the more infectious Delta variant of COVID-19. These factors act as headwinds to growth and weigh especially on EMEs, where progress on vaccination remains limited. This, combined with a more constrained policy space and deeper scarring effects from the pandemic, explain the divergence in their projected recovery path as compared with that of advanced economies.

The growth outlook for some key advanced economies has been revised upwards slightly compared with the June 2021 projections. A reprofiling of the government spending in the United States and a delayed projected recovery in Japan have led to some upward revisions in 2022. The growth outlook for EMEs has changed relatively little. Overall, world real GDP (excluding the euro area) is projected to increase by 6.3% this year, before decelerating to 4.5% and 3.7% in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Global activity had already exceeded its pre-pandemic level in late 2020. It is projected to narrow, though not close the gap to the path anticipated in the December 2019 staff projections by the end of the projection horizon.

An improved outlook for key trading partners leads to stronger euro area foreign demand. It is projected to increase by 9.2% this year and by 5.5% and 3.7% over the 2022-23 period – an upgrade for all three years compared with the June 2021 projections. These revisions reflect developments in advanced economies. Euro area foreign demand, which is now expected to be back on its pre-crisis trajectory in the course of 2022, has been systematically revised upwards since the June 2020 projections. These revisions largely reflected stronger than previously projected trade intensity during the recovery as well as the significantly improved outlook in the United States.

The projected global recovery from the pandemic crisis remains uneven. In advanced economies outside the euro area, the recovery is expected to proceed unabated, reaching its pre-pandemic path in early 2022, largely on account of the United States. In China, which was hit by the pandemic first, but recovered fastest amid strong policy support, real GDP reached its pre-crisis trajectory already late last year. In contrast, the recovery in other emerging markets is projected to be sluggish.

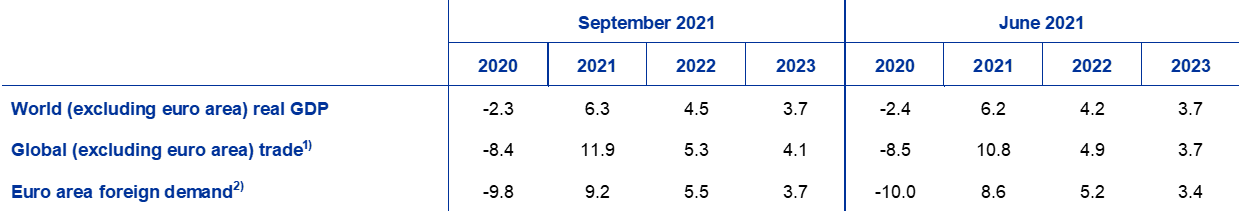

The international environment

(annual percentage changes)

1) Calculated as a weighted average of imports.

2) Calculated as a weighted average of imports of euro area trading partners.

Following export market share losses in 2021 related to temporary supply bottlenecks, exports are expected to expand at a robust pace, sustained by strong foreign demand and gains in competitiveness. The rapid increase in demand since the second half of 2020 is expected to continue to cause a mismatch between global supply capacity and demand conditions in 2021. This mismatch, COVID-19-related lockdowns and extreme events led to a combination of global logistic problems and a scarcity of some key intermediate inputs, which has weighed on euro area goods exports. Given that there continue to be shortages of some intermediate inputs, very elevated transport costs and long supplier delivery times, the bottlenecks are assumed to persist throughout 2021 and to gradually dissipate as of early 2022. Services trade, and in particular tourism, has recovered strongly during the summer amid successful vaccination campaigns that have allowed economies to reopen, although overall activity in the sector remains well below pre-crisis levels. Together with dissipating bottlenecks, this will allow euro area exports to pick up momentum in the medium term, given strong foreign demand and gains in export competitiveness following the recent depreciation of the euro exchange rate. Net exports are expected to provide a mildly positive contribution to annual real GDP growth in all three years of the projection horizon.

The unemployment rate declined in the second quarter of 2021 and is expected to remain broadly flat for the rest of the year, before falling to its pre-crisis level by early 2023. A stronger than expected expansion in employment growth in the second quarter of 2021, related to the stronger recovery in activity, led to a decline in unemployment. Temporary labour shortages reflecting increasing job reallocation and some mismatches are expected to affect the labour market in the short run for specific countries and sectors. A high share of workers in job retention schemes are assumed to return to regular employment, benefiting from the strong post-pandemic recovery. Accordingly, starting in 2022 the unemployment rate is expected to gradually decline and in early 2023 it is expected to drop below its pre-crisis level.

Labour productivity growth per person employed is expected to rebound sharply in 2021 before normalising gradually over the projection horizon. Having dropped sharply in 2020, it is estimated to have increased by 1.5% in the second quarter of 2021 (compared with the previous quarter), benefiting from a decline in the number of persons in job retention schemes. After peaking in the third quarter of 2021 it is projected to gradually moderate thereafter. The growth profile of productivity per hour worked has been much more resilient during the pandemic as total hours worked have more closely followed GDP developments.

Compared with the June 2021 projections, real GDP growth has been revised up in 2021 and is broadly unchanged in 2022 and 2023. Positive statistical carry-over effects from upward revisions to data in 2020 and a stronger outcome in the first half of 2021 more than compensate for a slightly weaker rebound in the second half of 2021 in the wake of tighter lockdown measures and more persistent supply-side bottlenecks than previously assumed. This has led to an upward revision to the projection for the year as a whole by 0.4 percentage points. For the remainder of the projection horizon, downward effects from the above headwinds and higher oil prices compensate for the moderately positive impact of lower lending rates, the weaker effective exchange rate of the euro and stronger foreign demand.

2 Fiscal outlook

Only limited further stimulus measures have been added to the baseline since the June 2021 projections. The estimate for the extraordinary fiscal stimulus in response to the pandemic in 2020 has been revised slightly upwards to 4.2% of euro area GDP. With 2022 budgets still in preparation, fiscal news since the June 2021 projections has been limited, but continues to point to additional COVID-19 crisis and recovery stimulus amounting to 0.2% of GDP in 2021. This reflects updated estimates of the fiscal cost of measures, expanded programmes and the adoption of new measures in many countries. Most of the additional measures are temporary, will be reversed in 2022 and relate mainly to subsidies and transfers to firms.

Overall, the discretionary stimulus related to the crisis and recovery is estimated at 4.6% of GDP in 2021, 1.5% in 2022 and 1.2% in 2023. In terms of the composition of the overall stimulus, the largest share in 2021 is still accounted for by subsidies and transfers, including those under job retention schemes, with the latter projected to be almost fully reversed in 2022. Measures classified under government consumption mostly include higher health expenditure, including wages, related to the vaccination campaigns. On the revenue side, the measures relate to cuts in direct and indirect taxes. Additional government investment was limited in 2020, but has a higher share in the stimulus packages as of 2021, mainly on the back of the ongoing NGEU financing. In addition to the COVID-19 crisis and recovery measures, in some countries, governments adopted further stimulus measures.[5]

The euro area fiscal stance adjusted for NGEU grants is projected to be expansionary in 2021, tighten notably in 2022, and remain broadly neutral in 2023. After the strong expansion in 2020, the fiscal stance – adjusted for the impact of NGEU grants on the revenue side – remains expansionary in 2021. The fiscal stimulus in 2021, as measured by the fiscal stance, is larger than implied by the COVID-19 crisis and recovery measures, mostly on account of measures not directly related to the crisis, including stronger structural expenditure growth, and methodological differences. Given the temporary nature of the emergency measures adopted in 2021 and the expected fading of the pandemic, the fiscal stance is projected to tighten notably in 2022 and to remain broadly neutral in 2023. Compared with the June 2021 projections, the fiscal stance has loosened slightly in 2021 and tightened over the rest of the projection horizon, especially in 2022.

The euro area budget deficit is projected to decline slightly in 2021 and more strongly as of 2022, with the fiscal outlook improving relative to the June 2021 projections. The decline in the budget deficit in 2021 reflects the improved cyclical component and lower interest payments, which more than offset the additional stimulus measures not covered by NGEU grants. The sizeable budget balance improvement in 2022 is mainly due to the unwinding of the COVID-19 crisis stimulus measures and a much more favourable cyclical component. In 2023, with a broadly neutral fiscal stance and better cyclical conditions, the aggregate budget balance is projected to increase further to just below -2% of GDP. Interest payments are projected to continue declining over the projection horizon and reach 1.0% of GDP in 2023. After the sharp increase in 2020, euro area aggregate government debt is expected to peak at around 99% of GDP in 2021. The decline thereafter is mainly due to favourable interest-growth differentials, but also to deficit-debt adjustments, which more than offset the continuing, albeit decreasing, primary deficits. The fiscal outlook has improved compared with the June 2021 projections. The euro area budget deficit and debt paths have been revised downwards over the entire projection horizon on account of the improved cyclical component and lower interest payments. The budget deficit and debt in 2023 remain significantly above the pre-crisis level of 2019, mainly on account of a higher expenditure ratio.

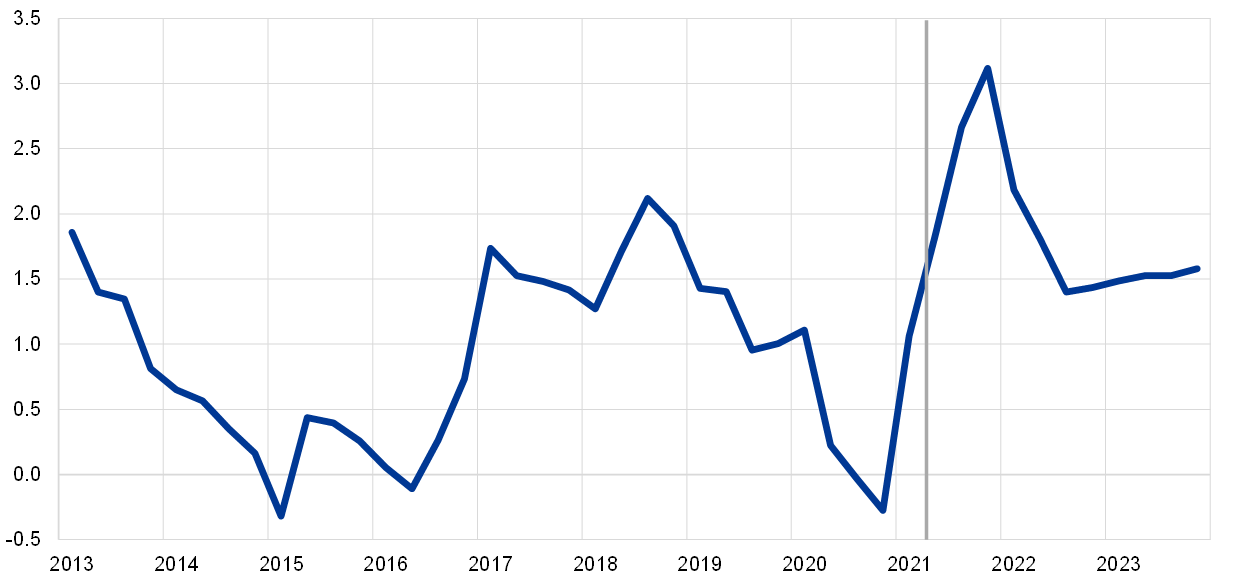

3 Prices and costs

HICP inflation is projected to continue to rise until the end of this year, to decline in the first half of 2022 and to gradually strengthen thereafter (Chart 3). Headline inflation is projected to average 2.2% in 2021, peaking at 3.1% in the fourth quarter of 2021 before declining to an average of 1.7% in 2022 and 1.5% in 2023. The spike in headline inflation in 2021 reflects upward effects from largely temporary factors, such as the rebound in the energy inflation rate amid strong base effects and the reversal of the German VAT rate cut. Increases in input costs related to supply disruptions and one-off re-opening effects on services prices, as COVID-19-related restrictions eased in the summer, have added to the upward pressure on inflation. Changes in HICP weights imply some volatility in the inflation profile in 2021 but, on average over the year, are expected to have only a small downward impact on HICP inflation. These temporary factors are expected to fade from the beginning of 2022. Also a further downward base effect from the surge in inflation in July 2021 dampens annual inflation in the third quarter of 2022. Thereafter, HICP inflation is expected to gradually increase over the remainder of the projection horizon, supported by the envisaged economic recovery. This is reflected in a strengthening of HICP inflation excluding energy and food over the projection horizon. Looking through the temporary surge in inflation in 2021, over the medium term a combination of increasing upward price pressures from the recovery in demand, while remaining somewhat muted, and indirect effects from past increases in commodity prices, including oil, should outweigh a reduction in upward price pressures from supply effects related to the pandemic. Increases in domestic cost pressures are envisaged to be the main driver of stronger underlying consumer price developments, while developments in external price pressures are expected to moderate over the latter half of the projection horizon. HICP food inflation is also expected to rise gradually. The moderately increasing upward price pressures on headline inflation from these two HICP components are somewhat offset in 2022 and 2023 by the envisaged declines in HICP energy inflation related to the downward sloping profile of the oil price futures curve.

Unit labour costs are expected to decline in both 2021 and 2022, driven by fluctuations related to the job retention schemes, before increasing by 1.4% in 2023. Following the strong increases in 2020 due to the sharp loss in labour productivity, unit labour costs are projected to be depressed by the rebound in labour productivity in 2021 and 2022, but to gradually increase by 2023. Both labour productivity and growth in compensation per employee have been subject to large swings in the presence of job retention schemes safeguarding employment. This pushed down the annual growth rate of compensation per employee in 2020 and has caused a subsequent rebound in the first half of 2021. As labour markets gradually recover over the projection horizon and the impact of the schemes fades, developments in compensation per employee are expected to normalise, with annual growth standing at 2.5% in 2023, somewhat above the rates seen prior to the pandemic. This mainly reflects the improvement in the labour market over the projection horizon. The projected strong rise in euro area headline inflation in the second half of 2021 is not expected to lead to significant second round effects on wage growth in the medium term.

Chart 3

Euro area HICP

(annual percentage changes)

Notes: The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. This chart does not show ranges around the projections. This reflects the fact that the standard computation of the ranges (based on historical projection errors) would not capture the elevated uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, alternative scenarios based on different assumptions regarding the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the associated containment measures and the degree of economic scarring are provided in Box 4.

Import price dynamics are expected to be strongly influenced by oil and non-oil commodity price movements and to reflect moderate external price pressures over the latter part of the projection horizon. The annual growth rate of the import deflator is expected to move from -2.5% in 2020 to 5.4% in 2021, largely reflecting increases in oil and non-oil commodity prices but also increases in other input costs related to supply shortages and the depreciation of the euro, before moderating to 0.8% in 2023. In addition to some assumed declines in oil prices, global price dynamics more generally are expected to remain moderate over the projection horizon and contribute to the moderate outlook for external price pressures.

Compared with the June 2021 projections, the projection for HICP inflation has been revised upward by 0.3 percentage points for 2021, by 0.2 percentage points for 2022 and by 0.1 percentage points for 2023. The upward revisions relate to HICP excluding food and energy across the projection horizon and to the energy component, especially in 2021 and 2022, while the food component is broadly unchanged. These revisions reflect a number of elements: recent positive data surprises; some upward pressures from more persistent supply disruptions; the improved demand outlook; the euro exchange rate depreciation; and upward revisions to the technical assumptions for oil prices (Box 1).

Box 3

Forecasts by other institutions

A number of forecasts for the euro area are available from both international organisations and private sector institutions. However, these forecasts are not strictly comparable with one another or with the ECB staff macroeconomic projections, as they were finalised at different points in time. They were also likely based on different assumptions about the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, these projections use different methods to derive assumptions for fiscal, financial and external variables, including oil and other commodity prices. Finally, there are differences in working day adjustment methods across different forecasts (see the table).

Comparison of recent forecasts for euro area real GDP growth and HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: MJEconomics for the Euro Zone Barometer, 19 August 2021, data for 2023 are taken from the July 2021 survey; Consensus Economics Forecasts, 12 August 2021, data for 2023 are taken from the July 2021 survey; IMF World Economic Outlook, 27 July 2021, data for 2023 are taken from April 2021 WEO; ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters, for the third quarter of 2021, conducted between 30 June and 5 July; European Commission Summer 2021 (Interim) Economic Forecast; OECD May 2021 Economic Outlook 109.

Notes: The ECB staff macroeconomic projections report working day-adjusted annual growth rates, whereas the European Commission and the IMF report annual growth rates that are not adjusted for the number of working days per annum. Other forecasts do not specify whether they report working day-adjusted or non-working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. This table does not show ranges around the projections. This reflects the fact that the standard computation of the ranges (based on historical projection errors) would not capture the elevated uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, alternative scenarios based on different assumptions regarding the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the associated containment measures and the degree of economic scarring are provided in Box 4.

The September 2021 ECB staff projections are higher than those of other forecasters for both growth and inflation over the early part of the horizon, but broadly in line for 2023. Across other institutions and private sector forecasters, real GDP in 2021 is expected at 4.3% in the (now somewhat outdated) OECD forecast and 4.8% in the case of the European Commission and Consensus Economics, with the ECB staff projections somewhat above this range at 5.0%. This may partly relate to a later cut-off date allowing the flash estimate of GDP in the second quarter of 2021 to be taken on board. For 2022 and 2023, the September projection is within a narrower range of forecasts. As regards inflation, the ECB staff projection is slightly higher for both 2021 and 2022, mainly due to higher expected inflation in the more volatile components, while for 2023 it is fully line with most other forecasters.

Box 4

Alternative scenarios for the euro area economic outlook

In view of the persistent uncertainty about the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic effects this Box presents two alternative scenarios to the September 2021 projections. These scenarios illustrate a range of plausible impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the euro area economy.

A mild scenario foresees a resolution of the health crisis by late 2021 and a strong rebound in economic activity, while a severe scenario assumes a protracted health crisis until mid-2023 and permanent losses in output. Compared with the baseline, the mild scenario envisages a higher vaccine effectiveness, also against new virus variants, and greater public acceptance of vaccines leading to only mildly increasing infections over time. This would allow for a swifter relaxation of containment measures and their phasing-out by late 2021, also leading to more limited economic costs and inducing strong positive confidence effects.[6] In contrast, the severe scenario envisages a resurgence of the pandemic in the coming months with the spread of more infectious variants of the virus, which also implies a reduction in the effectiveness of vaccines and a renewed tightening of containment measures, dampening activity.[7] Compared with the baseline, the severe scenario features more economic scarring, amplified by increased insolvencies and deteriorating borrower creditworthiness, which adversely affect banks’ expected losses and capital charges and consequently the supply of credit to the private sector. At the same time even in the severe scenario, monetary, fiscal and prudential policies are assumed to contain significant financial amplification effects. Broadly similar narratives underlie the scenarios for the global economy, while assuming a stronger deterioration in emerging market economies (partly due to lower vaccination rates) than in advanced economies in the severe scenario. Euro area foreign demand at the end of 2023 is about 13% above its pre-crisis level in the mild scenario, and around 5% above it in the severe one, compared with 10% in the baseline.

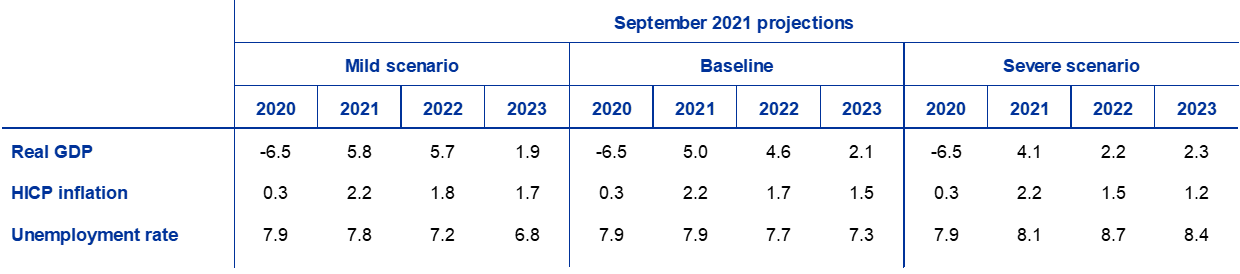

Alternative macroeconomic scenarios for the euro area

(annual percentage changes, percentage of labour force)

Note: Real GDP figures refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

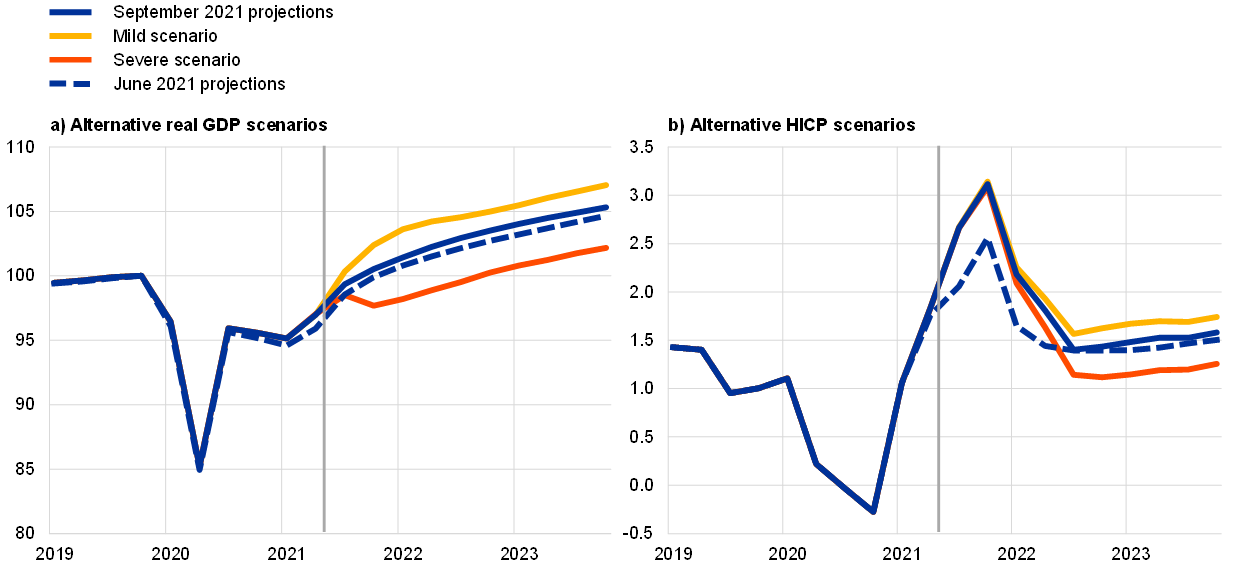

Euro area real GDP would rebound strongly in the mild scenario, returning to its pre-crisis level as early as the third quarter of 2021, while in the severe scenario it would reach this level only in late 2022 (Chart A). The mild scenario points towards a notable rebound in the second half of 2021 supported by strong positive confidence effects. These, together with the stronger than expected pick-up in high-contact services activity, induce a stronger increase in consumption, a more pronounced decline in the saving ratio, and a steeper decline in unemployment compared with the baseline. As a result, economic activity would be above the path envisaged in the pre-crisis December 2019 projections by early 2022. In the severe scenario, economic activity would expand moderately in the third quarter of 2021 and decline in the fourth quarter in line with the renewed tightening in containment measures. Economic growth in the severe scenario will underperform the baseline until late 2022. This is due to the more gradual relaxation of containment measures, further compounded by significant uncertainty, and adverse financial amplification mechanisms. While households remain cautious, maintaining an elevated saving ratio, the persistently high unemployment highlights the labour market risk, as corporate vulnerabilities and insolvencies intensify the need for labour reallocation. Somewhat higher growth in the severe scenario compared with the baseline is projected as from the end of 2022, given significant catch-up potential and successful adaptation to the new environment.

Despite being almost identical across scenarios in the short term, HICP inflation would decline to 1.7% and 1.2% in 2023 under the mild and the severe scenarios, respectively. This reflects the fact that the key drivers of the pick-up in inflation in the short term apply equally to both scenarios, while in the medium term the HICP variation between scenarios reflects mainly the different real economic conditions, and in particular the significantly larger amount of economic slack in the severe scenario.

Chart A

Alternative scenarios for real GDP and HICP inflation in the euro area

(chain-linked volumes, 2019Q4 = 100 (left-hand chart); annual percentage changes (right-hand chart))

Note: Data for real GDP are seasonally and working day-adjusted. The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

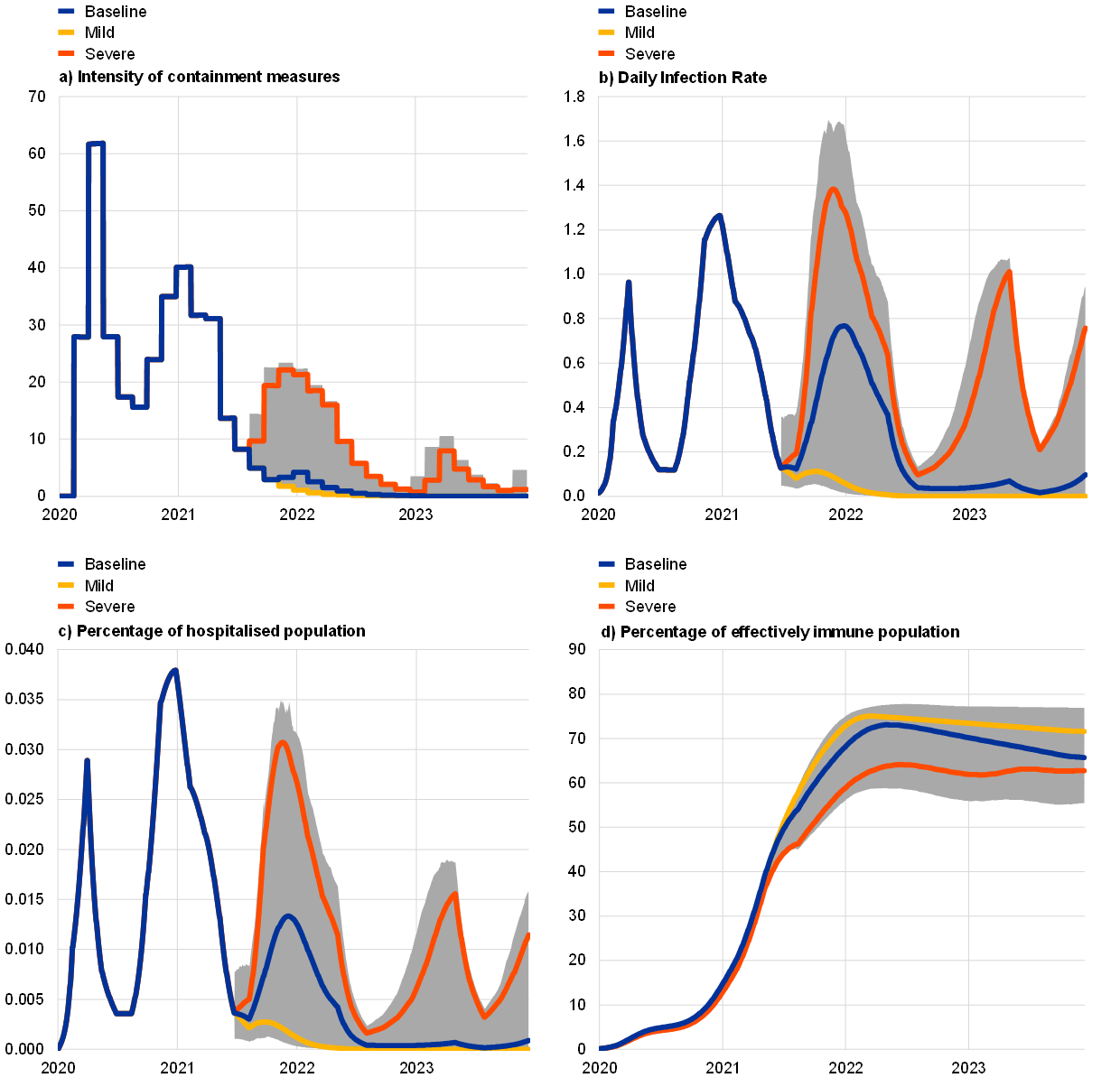

The scenarios are broadly supported by epidemiological model simulations that consider uncertainty regarding virus variants, the effectiveness of vaccines and reinfection risks. The ECB BASIR[8] is an extension of the ECB-BASE model[9] which addresses specific features of the COVID-19 crisis by combining an epidemiological model building on a standard susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) framework with a semi-structural large-scale macroeconomic model. In the range of pandemic outcomes generated by the ECB-BASIR model used to cross-check the scenarios, the severe scenario is characterised by higher infection rates, lower efficiency of vaccines and higher reinfection risk, and the mild scenario by the opposite, i.e. lower infection rates, higher vaccine efficiency and lower reinfection risks (Chart B). According to the ECB-BASIR, the more adverse features of the new virus variant assumed in the severe scenario result in a lower proportion of the population being effectively protected. This leads to a strong resurgence of infections and hospitalisations and requires stricter containment measures. The stricter containment measures have a stronger impact on mobility and therefore on economic activity. In contrast, according to the results of the model, the more benign epidemiological developments assumed in the mild scenario imply a rapid relaxation of containment measures and almost no remaining impact on mobility by late 2021.

Chart B

Pandemic simulations with the ECB-BASIR model

(index, maximum=100 (top left-hand panel) and percentage of population in all other panels)

Sources: Google Mobility reports, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and ECB calculations.

Notes: The grey areas represent the 90% confidence interval. The distribution is obtained by random simulations considering uncertainty about: i) the rate of vaccination U~[0.3% - 0.7%] with the baseline assuming 50%; ii) the effectiveness of vaccination U~[40%-80%], with the baseline assuming 60%, and reinfection uncertainty U ~[0%-4%] with the baseline assuming a reinfection rate of 2%; iii) the increase in the infection rate due to the new virus variant N~(60%, 16%); iv) SIR parameter uncertainty; v) uncertainty N~(52%, 10%) about learning effects (attenuation of macroeconomic effects from containment measures); and vi) historical uncertainty captured in residuals. The intensity of containment measures is estimated over history by ECB staff on the basis of Google Mobility data.

Box 5

Sensitivity analysis

Projections rely heavily on technical assumptions regarding the evolution of certain key variables. Given that some of these variables can have a large impact on the projections for the euro area, examining the sensitivity of the latter to alternative paths of these underlying assumptions can help in the analysis of risks around the projections.

This sensitivity analysis aims to assess the implications of alternative oil price paths. The technical assumptions for oil price developments are based on oil futures while exchange rates are held constant over the projection horizon. Two alternative paths of the oil price are analysed. The first is based on the 25th percentile of the distribution provided by the option-implied densities for the oil price on 16 August 2021, which is the cut-off date for the technical assumptions. This path implies a gradual decrease in the oil price to USD 47.9 per barrel in 2023, which is about 25% below the baseline assumption for that year. Using the average of the results from a number of staff macroeconomic models, this path would have a small upward impact on real GDP growth (around 0.1 percentage points in 2022 and 2023), while HICP inflation would be 0.1 percentage points lower in 2021, 0.5 percentage points lower in 2022 and 0.4 percentage points lower in 2023. The second path is based on the 75th percentile of the same distribution and implies an increase in the oil price to USD 80.8 per barrel in 2023, which is slightly more than 25% above the baseline assumption for that year. This path would have the same impacts on inflation and growth as the one for the 25th percentile, but with opposite signs.

© European Central Bank, 2021

Postal address 60640 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Website www.ecb.europa.eu

All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

For specific terminology please refer to the ECB glossary (available in English only).

PDF ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-21-002-EN-N

HTML ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-21-002-EN-Q

- The cut-off date for technical assumptions, such as those for oil prices and exchange rates, was 16 August 2021 (Box 1). The macroeconomic projections for the euro area were finalised on 26 August 2021. The current projection exercise covers the period 2021-23. Projections over such a long horizon are subject to very high uncertainty, and this should be borne in mind when interpreting them. See the article entitled “An assessment of Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections” in the May 2013 issue of the ECB’s Monthly Bulletin. See http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/index.en.html for an accessible version of the data underlying selected tables and charts. A full database of past ECB and Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections is available at https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browseSelection.do?node=5275746.

- This figure was revised up from the flash estimate of 2.0% initially published by Eurostat and which was included in the ECB staff projections shown in Charts 1 and 2.

- See also Box 2 entitled “Household saving ratio dynamics and implications for the euro area outlook”, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2021.

- The assumption for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields is based on the weighted average of countries’ ten-year benchmark bond yields, weighted by annual GDP figures and extended by the forward path derived from the ECB’s euro area all-bonds ten-year par yield, with the initial discrepancy between the two series kept constant over the projection horizon. The spreads between country-specific government bond yields and the corresponding euro area average are assumed to be constant over the projection horizon.

- Government announcements on budget support related to the recent flooding and other extreme weather events have, apart from in some limited cases, not been included in the baseline as the measures have not yet been sufficiently well-specified.

- In the baseline, a full relaxation of containment measures is assumed to occur in early 2022.

- Given the difficulties involved in predicting the timing of further intensifications of the pandemic, the scenario takes the possibility of a further resurgence of the virus beyond early 2022 into account by distributing the economic impact over the period until the health crisis is resolved.

- See Angelini, E., Damjanović, M., Darracq Pariès, M. and Zimic, S., “ECB-BASIR: a primer on the macroeconomic implications of the Covid-19 pandemic”, Working Paper Series, No 2431, ECB, June 2020.

- See Angelini, E., Bokan, N., Christoffel, K., Ciccarelli, M. and Zimic, S., “Introducing ECB-BASE: The blueprint of the new ECB semi-structural model for the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2315, ECB, September 2019.

- 9 September 2021