Communicating the complexity of unconventional monetary policy in EMU

Speech by Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the 2017 ECB Central Bank Communications Conference, Frankfurt am Main, 15 November 2017

Central bank communication has been fundamentally affected by the fallout from the global financial and economic crisis.[1] Throughout that period, central banks succeeded in preventing a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. To do so, they adopted a broad range of unconventional measures, the functioning of which is very difficult to explain to the public. This applies, for example, to the notion of negative nominal interest rates, which is hard to communicate because it challenges the conventional wisdom that thrift and patience are virtues that deserve pecuniary remuneration. Against this backdrop, I would like to discuss three communication challenges that are particularly relevant to the euro area and the ECB’s monetary policy.

The first challenge is to bear in mind the multi-country nature of our monetary union, which requires communication to be tuned to the specific context of different national audiences so as to ensure broad participation in the public debate on euro area monetary policy.

The second challenge for monetary policy communication is to take into account the increasing complexity of monetary policy by ensuring consistency over time and clarifying the state contingency of the policy stance. To ensure consistency over time, it is essential for the central bank to adopt a clear organising framework, centred on the ultimate objective, for the ECB consisting of price stability, and adhering to a state-contingent reaction function that determines how the monetary policy stance adjusts to changing economic conditions. As the economic environment that monetary policy faces may indeed be subject to massive swings, state contingency may entail pronounced differences in the monetary policy stance over time. This, in turn, requires careful explanation – in particular in circumstances that call for unconventional measures and, hence, leave markets and the general public without empirical precedent to help them anticipate and rationalise the central bank’s actions.

The third challenge is for the communication framework to provide clarity on the use of specific tools in a multi-instrument context, when the central bank reaction function acquires an additional dimension. In normal times, the central bank reaction function mainly specifies the contingencies for loosening, tightening or maintaining a given policy stance. In unconventional times, it also needs to spell out which tool would provide the first margin of adjustment if a change in policy stance were to appear warranted, and how the adjustment in one policy instrument would interact with the others.

Reflecting the multi-country nature of Economic and Monetary Union

To gauge the complexity of monetary policy communication in a multi-country currency union, just consider some of the headlines on the expanded asset purchase programme (APP) which appeared in major newspapers in different countries, both inside and outside the euro area, in January 2015.

Starting from the outside perspective, reports in media outlets in the United States and the United Kingdom spanned the full spectrum, with some saying that the ECB’s “bond-buying proposal beats all expectations” and the ECB “gets it (almost) right”, while others felt that the “stimulus may be too little or too late”.

Within the euro area, newspapers in some countries claimed the ECB was a “central bank going the wrong way”, as the APP would fuel inflation and “make everything more expensive”. In other countries the tone was markedly different, with the programme considered “convincing” and conducive to an economic environment in which “there’s no excuse for the recovery not to start”.

In addition to this wide range of media perspectives, the crisis has had a profound impact on the way in which the public views institutions. For instance, judging from different Eurobarometer surveys, trust in European institutions, including the ECB, clearly declined during the crisis and has only started to recover in recent years (see Figure 1), while remaining consistently higher than the levels of trust enjoyed by national governments and parliaments. The fall and rise in public trust in turn runs roughly in parallel with the performance of the economy, as reflected in, for instance, the unemployment rate – a point that also emerges from systematic empirical analysis.[2]

These levels of trust often coincide with a disconnect between, on the one hand, the way central banks communicate their policies and, on the other hand, the public’s perception and awareness of the goals that central banks try to achieve and the means by which they operate.[3] As Andy Haldane remarked earlier this year, this disconnect means that we, as central bankers, have to “rethink how and with whom we engage”.[4]

Figure 1: Evolution of trust in different European and national institutions and economic conditions

(net percentages)

Sources: Standard Eurobarometer No 87, published on 2 August 2017, and Eurostat.

Notes: The figure shows the net trust in the respective institutions, defined as the percentage of respondents who trust the institution minus the percentage of respondents who distrust it, and the euro area unemployment rate (inverted). The Eurobarometer survey is conducted twice a year in spring (S.) and autumn (A.).

Figure 2: Cross-country dispersion in net trust in the ECB in euro area countries

(standard deviations of survey results across countries)

Source: Standard Eurobarometer No 87, published on 2 August 2017.

Notes: The figure shows the standard deviation in net trust in the ECB across euro area countries for different survey rounds. Net trust in the ECB is the percentage of respondents who trust the ECB minus the percentage of respondents who distrust the ECB. The survey is conducted twice a year in spring (S.) and autumn (A.).

The level of trust in the ECB also differed greatly across countries in the years following the crisis and the dispersion still remains above pre-crisis levels despite some recent declines (see Figure 2). Such widely differing perceptions across countries pose a challenge for central bank communication in our monetary union.

The ECB has sought to address this challenge with what I would refer to as a “two-layered federal structure of communication”.

The first layer consists of a set of “centralised” communication channels through which the ECB discharges its duty to explain its euro area-wide policy conduct to the public and fulfils the accountability requirements vis-à-vis elected representatives as required by the Treaties.

These channels include: the introductory statements at the press conferences following the Governing Council’s monetary policy meetings, in which the President explains our decisions and summarises the economic and monetary analysis on which they were based; the monetary policy accounts, which report, with additional detail, the deliberations leading up to the Governing Council’s decisions; speeches by Governing Council Members; a panoply of publications bringing together the economic, monetary and financial information that serves as input to the underlying policy assessments; and our public accountability vis-à-vis the European Parliament, in the form of our Annual Reports, the President’s testimony before the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, and our replies to questions from Members of the European Parliament.

These centralised communication channels are complemented by “decentralised” communication channels at national level where, in particular, the national central banks of the Eurosystem play an integral role. Equipped with in-depth knowledge of their respective economies, and – literally and figuratively – sharing a common language with their audiences, national central banks are essential in explaining ECB policies to the broader public in their countries. This communication with national audiences is also important given that economic conditions may at times diverge in different parts of the euro area. The national central banks are then well placed to correct the potential dissonance between the rationale of monetary policy actions tailored to the conditions of the euro area as a whole and those that national audiences may consider more appropriate for their own economies. Explaining the common monetary policy stance in a national context is in practice a very challenging task, especially when countries are hit by asymmetric shocks.

Reflecting the increasing complexity of monetary policy

The challenge for communication to preserve consistency, acceptance and trust across geographies is accompanied by another, no less intricate, challenge: ensuring consistency over time.

Central banks’ monetary policy instruments have undergone a sea change over the last decade. The policy-controlled short-term interest rates of the ECB, the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan dropped from levels between 4% and 5% to essentially zero (see Figure 3) in a relatively short space of time. Since the beginning of the crisis, these central banks’ balance sheets have grown significantly above levels that for decades had been considered typical (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Key monetary policy interest rates

(percent)

Sources: ECB, Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan and Bank of England.

Notes: Deposit facility rate and (dashed) main refinancing rate (ECB), Federal Funds Target Rate (Federal Reserve), Uncollateralized Overnight Call Rate (Bank of Japan) and Official Bank Rate (Bank of England).

Latest observation: 31 October 2017 (Bank of Japan), 6 November 2017 (ECB, Federal Reserve, Bank of England)

Figure 4: Central bank balance sheets

(total assets; index=100 in 2007)

Source: ECB, Federal Reserve, Bank of England and Bank of Japan.

Notes: The Bank of England’s balance sheet is approximated after 24 September 2014 since the institution only discloses 90% of its consolidated balance sheet after this date.

Latest observation: 3 November 2017 (ECB, Federal Reserve), 27 October 2017 (Bank of England) and 1 October 2017 (Bank of Japan).

Such a profound change in policy conduct requires us to carefully explain that consistency does not mean constancy. Consistency means that we are faithful to our mandate and seek to deliver the monetary policy stance that, given the prevailing economic conditions, maximises our chances of attaining our objective over the policy-relevant horizon. Pursuing our mandate has entailed pronounced shifts in the frequency of policy changes and in the nature and composition of instruments.

What is important, however, is that these shifts are governed by a clear organising framework which: (i) centres on the ultimate objective, price stability for the ECB; (ii) embeds a view on the monetary policy transmission mechanism that maps policy measures with the ultimate objective; and (iii) yields a reaction function that determines how the monetary policy stance adjusts to changing economic conditions. This organising framework provides a way for us to manage the difficult balancing act of responding to material changes in the outlook for price stability in a timely manner, while ensuring that there is sufficient evidence to justify our actions.

The key economic rationale for monetary policy communication is to make this reaction function understood by markets and the broader public. It does so not only by announcing the prevailing policy but also by stating the reasons and detailing the assessments that led the central bank to adopt it, thereby allowing observers to more efficiently infer patterns than would be possible without such communication.

Moreover, in recent years, many central banks have gone a step further to make their reaction function more transparent and concrete. Communication on the prevailing policy and the thinking behind it has been complemented by guidance on the future policy course. In providing forward guidance on their main policy tools, central banks have specified the time period over which they expect or intend to preserve a certain instrument calibration and stipulated the contingencies that would warrant a change in instrument calibration.

This innovation in the communication framework has directly served to signal consistency in policy conduct at a time when, first, proximity to the effective lower bound on policy-controlled short-term interest rates might have raised doubts as to the central bank’s options to deliver the requisite amount of monetary easing; and, second, the adoption of new, previously unknown, policy tools left observers without a clear historical reference point to gauge the central bank reaction function. Furthermore, especially in its outcome-based formulation, forward guidance has explicitly maintained the state contingency of policy conduct and established a clear link between the policy objective and the future evolution of policy tools – a consideration that also formed the backdrop for the Governing Council’s decision in October to reconfirm the outcome-based element of its forward guidance on the expanded asset purchase programme, which remains contingent on a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation.

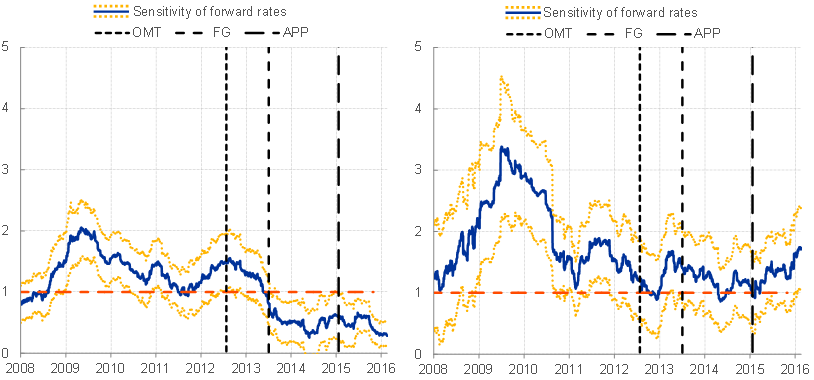

Overall, our forward guidance framework has left a clear imprint on the market’s ability to gauge our policy intentions. One potential metric by which to measure the effectiveness of forward guidance on key ECB interest rates is the sensitivity of forward rates to macroeconomic news. In the presence of clear guidance on the policy rate path, forward rates which embed investors’ rate expectations should be less reactive – over short to medium-term horizons – to macroeconomic surprises and instead be anchored by central bank communication. Observing this metric over time, it becomes clear that the introduction of our measures – including the forward guidance on policy rates – has been followed by a pronounced decline in the sensitivity of forward rates at the shorter end of the term structure, where monetary policy expectations have the biggest impact, while rates at the longer end have remained around their historical average (see Figure 5).[5] Moreover, the more muted responsiveness that accompanied the introduction of the policy package in mid-2014 also went along with a pronounced flattening of the short to medium-term segment of the forward curve (see Figure 6).[6]

Figure 5: Time-varying sensitivity of the three-month OIS in two years’ (LHS) and ten years’ (RHS) time

(normalised to 1)

Source: ECB. Estimation is based on Altavilla C., Giannone D. and Modugno M. (2017), "The Low Frequency Effects of Macroeconomic News on Government Bond Yields", forthcoming in Journal of Monetary Economics.

Note: For each maturity, the blue line indicates the sensitivity of forward rates to macroeconomic surprises. The yellow lines represent the associated confidence bands. When larger (smaller) than one, the sensitivity is higher (lower) than historical regularities. Vertical gridlines indicate the announcement dates for the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), forward guidance (FG) and the expanded asset purchase programme (APP).

Figure 6: Expectations of future short-term rates in the euro area in periods of ECB non-standard measures

(percentages per year)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Note: Evolution of the overnight index swap forward curve from pre-negative interest rate policy (black dotted lines) to post-negative interest rate policy (red dotted lines) period.

We have been communicating about our asset purchase programme by disclosing two parameters: the pace of purchases per month, and a date by which the Governing Council could end the net purchases, provided we, by that date, see a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with our inflation aim.

This combination of date-based and outcome-based forward guidance has made it easier for market participants to calculate the stimulus being provided each time our programme has been (re)calibrated. The date-based element suggests the minimum amount of stimulus that the programme could be expected to deliver. The outcome-based element – very fundamentally – ties the programme to our inflation aim.

Have market expectations internalised the state-contingent nature of our monetary policy? And which element has prevailed in shaping market expectations: the date-based or the inflation-contingent element?

Market expectations for the likeliest terminal date of the APP have not coincided with the “expiry date” communicated in the most recent programme recalibration, but have instead typically extended beyond this expiry date. In other words: in forming their predictions about the most likely date for purchases to end, markets have not just looked at the date-based element of our guidance. They have also considered the outcome-based element, which allows for the possibility of a purchase horizon extending beyond the expiry date, if that is necessary to attain a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation. This, in turn, indicates that the state contingency of the APP has been well understood by market participants.

Clarifying the interaction between monetary policy instruments

In normal times, central banks adapted their monetary policy stance by influencing the level of one short-term interest rate. In unconventional times, communication has had to cope with the new challenge of explaining the complementarities between policy tools, as non-standard monetary policy has become multidimensional.

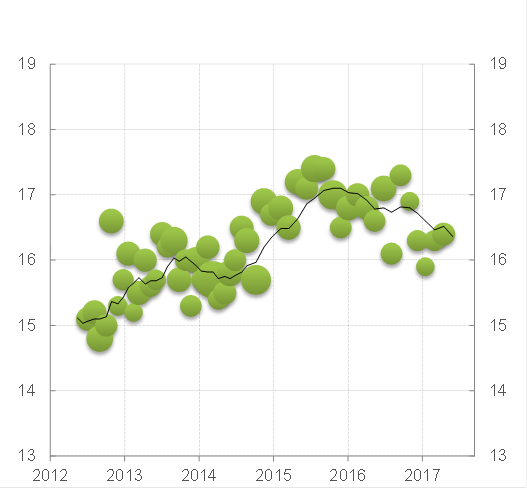

To ensure that their reaction function is understood, central banks have to explain how their policies take into account these essential complementarities in the transmission of the individual tools – although this may significantly increase the complexity of the messages they have to convey. In this context, it is perhaps no coincidence that the complexity of the introductory statements delivered at the ECB’s press conferences, as measured by common indices of text readability, has also increased, and started to do so just around the time when we began the latest round of non-standard measures in mid-2014 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: ECB introductory statements – reading grade level (in years of education; see y-axis) and number of words

Source: ECB introductory statements.

Notes: Flesch-Kincaid (FK) reading grade level of introductory statements by release date. Higher values on the scale indicate higher complexity. The higher the number of words, the larger the bubbles. The curve plots the six-month moving average. The FK reading grade level is calculated using MS Word. Latest observation: 26 October 2017

A multi-instrument policy toolkit is more complex because it adds a further dimension to the central bank reaction function. It not only has to map contingencies with modifications of the policy stance – it also needs to clarify which tool would provide the first margin of adjustment if a change in the policy stance were to appear warranted and how the adjustment in one policy instrument would interact with the others.

This evolution in the policy toolkit has been fully reflected in the evolution of the ECB’s approach to forward guidance in the different phases of the crisis. Forward guidance on interest rates was first adopted in July 2013 as a means to insulate the euro area from the global financial turmoil that had followed the so-called taper tantrum episode a few weeks earlier. This proved to be an effective firewall. But the subdued inflation outlook, as well as other headwinds to the euro area recovery, stemming from, for instance, subdued bank credit, required a more comprehensive policy package. So in the summer of 2014 we launched a complex package of policy measures that were to be adopted in a sequential and state-contingent manner as economic conditions evolved.

Given the essential interaction between policy tools in their transmission to the economy, the ECB accompanied the expanded asset purchase programme that it announced in January 2015 with an adjustment to the forward guidance framework, moving from a previously singular focus on policy rates to a dual approach combining and integrating the different elements of guidance on policy rates and asset purchases (see Figure 8).[7]

Communication about the intended horizon of net asset purchases and the expected future path of policy rates has been a key component of our policy strategy. Our forward guidance on policy rates has acted as an enabling condition for the purchases to exert their full impact. In the absence of reassurances that policy rates would remain anchored around levels close to their lower bound for the entire life of the net purchases, the downward impact of asset purchases on term premia could have been partly neutralised by expectations of rate increases. At the same time, the conditionality attached to the intended horizon and size of our net asset purchases has reinforced the signalling power of our forward guidance on rates.

Figure 8: Evolution of ECB forward guidance framework

Looking ahead, as we progress towards a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation and approach the time when net purchases will gradually come to an end, the residual monetary support needed to assist the economy in its transition to a new normal will increasingly come from forward guidance on our policy rates. Policy rates will eventually regain their status as the main instrument of policy, and our forward guidance will revert to a singular approach.

Conclusion

Monetary policy communication faces several distinct challenges. It has to be accessible to and useful for a variety of audiences. It has to be consistent in diverse economic circumstances. And it has to clearly convey the central bank’s reaction function, also when the latter entails a diverse set of instruments.

To meet these challenges, the ECB’s communication uses a broad range of channels to express the Governing Council’s policy intentions at euro area level and to explain it to national audiences. It has made further efforts to make this reaction function understood by markets and the broader public, not least by providing detailed information on the thinking underlying its actions. And, in recent years, it has made its reaction function more transparent and concrete by adopting an integrated forward guidance framework.

We will continue to engage with the general public and to guide market expectations as new challenges arise. This means that we have to continue reflecting and having constructive debates on how to shape central bank communication in the future.

[1] I would like to thank Federic Holm-Hadulla for his support in the preparation of this speech.

[2] See, for instance, Ehrmann M., Soudan, M. and Stracca, L. (2013), Explaining EU citizens’ trust in the ECB in normal and crisis times, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 115(3), pp. 781-807. It is also interesting to note that deteriorating economic and fiscal conditions in one euro area country seem to reduce the level of trust in the EU of citizens in other countries; see Ioannou D., Jamet, J.-F. and Kleibl, J. (2015), Spillovers and Euroscepticism, Working Paper Series, No 1815, ECB.

[3] In this vein, see also the evidence in Ehrmann et al. (2013), which indicates that a “higher degree of knowledge about the ECB generates more trust in normal times and even more so during the financial crisis”.

[4] See the speech given by Andrew G. Haldane, Chief Economist, Bank of England entitled A Little More Conversation, A Little Less Action at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy Conference on 31 March 2017.

[5] See also Coenen, G., Ehrmann, M., Gaballo, G., Hoffmann, P., Nakov, A., Nardelli, S., Persson, E. and Strasser, G. (2017), Communication of monetary policy in unconventional times, Working Paper Series, No 2080, ECB, and the references quoted therein.

[6] Given the unique structure of the euro area’s monetary policy transmission mechanism, anchoring the short and intermediate segments of the yield curve around levels consistent with a very accommodative monetary policy stance has been even more critical for the ECB than for other central banks engaging in similar policies. For further details, see my speech at the Fixed Income Market Colloquium in Rome on 4 July 2017.

[7] For additional details on the rationale of this forward guidance framework, see my remarks at the MMF Monetary and Financial Policy Conference on 2 October 2017 in London.

Banc Ceannais Eorpach

Stiúrthóireacht Cumarsáide

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, an Ghearmáin

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Ceadaítear atáirgeadh ar choinníoll go n-admhaítear an fhoinse.

An Oifig Preasa