Risk Sharing and Macroprudential Policy in an Ambitious Capital Markets Union

Speech by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB,at the Joint conference of the European Commission and European Central Bank on European Financial Integration and Stability,Frankfurt am Main, 25 April 2016

Ladies and gentlemen,

An integrated and developed capital market is of key relevance to the European financial system and the economy as a whole. In my speech today, I would like to provide a foundation for this statement from two interlinked perspectives. First of all, well-functioning capital markets are particularly beneficial for an area like the euro area if they lead to what economists call “financial risk-sharing”. At the same time, however, the process of financial integration and capital market development that can enhance such risk-sharing may be accompanied by the emergence of new financial stability risks that could undermine the envisaged benefits. Therefore, in order to reap the benefits of a true Capital Markets Union (CMU), we need to provide the conditions under which capital markets can flourish, whilst at the same time making sure that regulatory and supervisory measures keep financial stability risks in check.

In order to make progress on how this balance can be struck, I shall first review the case for cross-country risk-sharing via capital markets, review the evidence for the euro area and consider how it can be enhanced. Next, I shall discuss the threats to financial stability that can be associated with complementing a more bank-based financial system, like the European one, with strengthening capital markets. Third, I shall let you know my views on which macroprudential policy reforms should be considered.

The benefits of financial risk-sharing for the euro area

One of the main reasons why financial integration is beneficial is that integrated financial markets help support constant consumption growth “in good and in bad states” of the world.[1] Consumption smoothing between countries, also known as risk-sharing, can increase welfare by hedging consumption against country-specific risks. In theory, in a perfectly integrated world, full risk-sharing can be achieved where consumption in regions or countries grows at a constant pace and is insensitive to local fluctuations in income and wealth.

Normally, high levels of risk-sharing are achieved across jurisdictions within a country, or within a federation that represents a functioning political, economic, and monetary union. For example, evidence suggests that three quarters of shocks to per capita gross product of individual states in the United States are smoothed, with about 40 percent smoothed by insurance or cross-ownership of assets, a quarter smoothed by borrowing or lending, and one-eighth smoothed by the federal transfers and grants. In other words, the contribution of markets is five times higher than the contribution of fiscal tools.[2] Regions within federations in Europe exhibit high levels of risk-sharing, too. For example, in pre-unification Germany, virtually all shocks to per capita state gross product were smoothed. However, due to less developed capital markets than in the United States, the largest portion – 50 percent – was smoothed through the federal tax transfer and grant system, and 36 percent were smoothed through financial markets.[3]

For countries in a monetary union such as the euro area, risk-sharing is particularly important because the single monetary policy is unable to address asymmetric shocks. With disjoint business cycles across countries, idiosyncratic shocks to EMU member states need to be insured through robust market or fiscal mechanisms. Reducing the volatility of aggregate consumption through various risk-sharing mechanisms can provide significant welfare gains for countries hit by specific shocks. And, by reducing internal divergences and facilitating macroeconomic adjustment, risk-sharing can be beneficial for the monetary union as a whole.

At this point it is quite clear that, in the foreseeable future, a number of mechanisms that have the potential to improve risk-sharing across countries will not progress quickly in Europe. For example, labour mobility will likely remain below levels achieved in common-language federations such as the United States or Germany. Similarly, building a European supra-national system of taxes and transfers to mimic the United States or the situation within some European countries is, at present, not a realistic prospect. Finally, the rules on fiscal deficits imposed by the Stability and Growth Pact will continue to set limits on national governments for smoothing large shocks.

For these reasons, it is more pressing than ever to boost Europe’s risk-sharing potential through financial market mechanisms. First, cross-border holdings of productive or financial assets can provide members of a currency union with insurance against idiosyncratic shocks. Second, well-functioning credit markets can contribute to smoothing consumption against relative income fluctuations, especially if most cross-border lending takes the form of direct lending to households and firms rather than of wholesale lending and borrowing in interbank markets.[4] The conclusion is that greater progress in risk-sharing in the euro area would require significantly more developed and integrated capital markets, as well as more banks operating at a pan-European level.

Quantitatively, the risk-sharing benefits of integrated financial markets can be large. By far the most important source of risk sharing are cross-regional and cross-border asset holdings, that is, various forms of equity holdings and firm ownership claims. Financial integration in Europe was expected to be greatly facilitated by the introduction of the common currency. However, in the years since the introduction of the euro, progress in capital markets and credit markets integration has been uneven. At present, the cross-border ownership of assets in the EU is still limited, despite the fact that the single currency in the euro area reduced some of the information barriers and transaction costs. Corporate financing through bond and equity markets is much more limited in Europe too, with banks being the undisputed primary source of funding for firms.

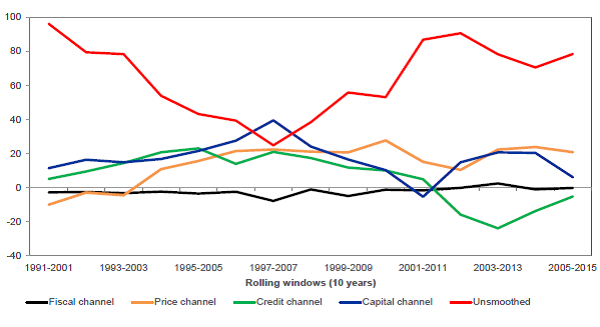

For all these reasons, the overall contribution of markets to risk-sharing has, on average, been somewhat limited.[5] Chart 1 demonstrates the contribution of various factors to risk-sharing over time. It shows that after the adoption of the euro, smoothing through factor income flows resulting from cross-border ownership of assets increased substantially, yet it remained on average below US levels. The notable exception is a brief period in the early-to-mid 2000s when capital markets smoothed between 30 and 40 percent of country-specific shocks to GDP. The contribution of capital markets declined substantially during the financial crisis and especially during the sovereign debt crisis. The contribution of credit markets has been lower, and it became even negative during the financial crisis when the European banking sector was particularly heavily hit. At present, almost 80 percent of the idiosyncratic shocks to a country’s economy remain unsmoothed, and changes in relative prices contribute the most to risk-sharing.

Contributions of various channels to risk sharing in EA, 1991 – present[6]

To speed up the process of capital markets and credit markets integration, two initiatives have emerged in Europe: the Banking Union and the Capital Markets Union (CMU). The Banking Union aims at a sustainable and deep integration in banking markets, through single supervision, joint resolution and common deposit insurance. Risk-sharing is particularly fostered through direct cross-border bank lending, emphasising the importance of the European Commission’s recent initiative on fostering retail financial services. The CMU, in turn, aims at mobilising capital by creating deeper and more integrated capital markets in the EU. Ideally, the CMU should achieve the completion of the single market for capital within a common-currency union. This completion is vital to reap the full benefits of risk-sharing across borders and not be limited by border effects from past institutional legacies. Overcoming these border effects is to be achieved through regulatory and non-regulatory actions, including the harmonisation of key legislation related to financial products. While the regulatory and non-regulatory actions will be instrumental in capturing market-provided risk-sharing, deeper capital markets have a particularly high potential to smooth risks across national borders.

Consequently, we need an ambitious CMU which requires a concrete roadmap in terms of goals and milestones. Broad objectives such as capital market development, deepening financial integration and achieving risk-sharing should be at par with specific proposals such as facilitating funding for corporates in general and for SMEs in particular. Key areas such as securitisation, insolvency regimes, securities holders’ rights and tax legislation need to be prioritised. All these are important to ensure equal treatment of users of capital markets across Member States, the very essence of a CMU.

Financial stability implications of enhanced risk-sharing and other aspects of capital market development

This brings me to the second part of my talk, where I would like to discuss the financial stability implications of enhanced risk-sharing. Indeed, financial integration and the further development of non-bank financing may also create new financial stability risks.

At a general level, greater integration can exacerbate the size and speed of cross-border contagion. International risk-sharing and cross-border contagion can be two sides of the same “financial integration coin”.[7] This explains why taking a macroprudential perspective on the financial system is extremely important for addressing potential new sources of systemic risk.

With respect to the banking sector, the further development of capital markets increases competition and may incentivise banks to take on more risk to maintain profitability.[8],[9] To ensure that there are no unintended financial stability risks, we need to strengthen the European macroprudential regulatory toolkit for banks under the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV)/Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR).

The European Commission’s review of the CRR/CRDIV will provide an opportunity to revise and complement the current macroprudential toolkit for banking at the European level. It should entail, firstly, ensuring that instruments currently available are more targeted and overlaps are eliminated; secondly, broadening the toolkit with additional instruments such as the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), Leverage Ratio (LR), Loan-to-Value (LTV)/Loan-to-Income (LTI) and Debt-Service-to-Income (DSTI) ratio; and thirdly, streamlining the process for notification or information procedures both in the EU and within the SSM, by revising in particular Art 458 CRR. This would simplify the co-ordination mechanism, ensuring that macroprudential authorities can decide and implement the measures in an effective, efficient and timely manner.

Moreover, the strong growth of non-bank financing creates new risks in a part of the financial system that is much less regulated. In particular, the investment fund sector has grown rapidly over the past few years. Between end-2009 and the first quarter of 2015, assets managed by investment funds other than money market funds almost doubled from €5.4 trillion to €10.5 trillion. Excluding valuation and reclassification effects, the sector has grown by 30 percent since 2009.[10]

Importantly, this rapid growth comes together with increased risk-taking. Funds have shifted their asset allocation from higher- to lower-rated debt securities, increased the average residual maturities of debt securities’ holdings and continued to expand their exposure to emerging markets.[11] In addition, the interconnectedness of the fund sector with the financial system, the wider use of synthetic leverage, and the increasing prevalence of demandable equity imply that the potential for a systemic impact would increase, should the investment fund industry come under stress.

Therefore, I want to clearly state that the financial regulatory reform has to be completed and extended through further efforts to contain risks in the shadow banking sector and to strengthen macroprudential policies.

Developing the macroprudential framework beyond banking

Please allow me to elaborate on three important aspects of this task, namely tools to address the excessive use of leverage by investment funds, tools to address liquidity risks, and a framework for macroprudential margin and haircut requirements.

As regards leverage in investment funds, we need to ensure that the use of leverage remains within acceptable limits. Highly leveraged funds can create and amplify systemic risk. When leverage is created through derivatives’ exposures or repo and securities lending transactions, margin calls or increasing haircuts on collateral can trigger a deleveraging by funds.[12] Notably, such a “margin spiral”[13] can even occur when funds are closed and investors cannot redeem their shares at short notice. To the extent that many funds are forced to sell assets in less liquid markets and at substantial discounts, this can reinforce price falls in financial markets and become a risk of systemic nature.[14]

In order to curb the use of leverage by investment funds in the EU, it is useful to distinguish between funds that are subject to the regulatory framework of the Undertakings for Collective Investments in Transferable Securities (UCITS) Directive and those subject to the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD).

In principle, all UCITS-funds have restrictions on the use of balance sheet and synthetic leverage. In practice, however, funds applying more complex investment strategies can calculate their use of leverage based on the Commitment Method or a Value at Risk (VaR) approach, resulting in a less stringent limit for synthetic leverage. Therefore, it is important that we examine the use of leverage by these UCITS-funds, and address any existing shortcomings in the UCITS regulations.

As for the alternative investment funds that operate under the AIFMD, there are no hard limits for the use of leverage. Importantly, national competent authorities do have the power to impose leverage limits under the AIFMD, but no authority has exercised this power so far. In order to put this potentially powerful macroprudential tool into practice, we need to develop an operational framework at the EU level. In this context, let me highlight three important issues.

First, the use of leverage within the banking system and the existing leverage ratio for banks may not always be a useful benchmark for all types of funds. Unlike bank capital, investment fund shares of open-ended funds can be an unstable source of funding when investors can withdraw their equity at short notice.[15]

Second, an assessment of liquidity risk by funds should be part of the assessment of leverage. Indeed, the risk of redemptions by investors on open-ended funds can be closely related to the use of leverage.

Third, the framework should have a clear macroprudential perspective, providing authorities with the guidance and flexibility to set limits for groups of funds, where necessary to address a “too many to fail” risk.[16] Even if investment funds are small and thus not “too big to fail”, they may be “systemic as a herd”, and pose a risk to financial stability due to common exposures to the same type of shock.[17]

Next to tools addressing excessive leverage, we need to develop tools targeting liquidity in non-bank financial institutions. With regard to investment funds, “liquidity spirals” remain a risk.[18] Such spirals could be triggered if funds were to be confronted with high redemptions[19] or increased margin requirements, as these could result in forced selling on markets with low liquidity. To address such risks, guided stress tests could be developed jointly by ESMA, ECB and ESRB, together with national competent and macroprudential authorities, and additional intervention powers for competent authorities to deal with large scale redemptions should be discussed. As regards the latter, the UCITS directive already provides member states with the option to allow competent authorities to require the suspension of the repurchase or redemption of units in the interest of the unit-holders or of the public. We should explore whether this provision can be effectively used for macroprudential purposes.

Finally, the creation of leverage via derivatives and securities financing transactions (SFT) and the pro-cyclical effects of margin and haircut-setting practices in these transactions would also need to be addressed. Macroprudential authorities should be given the power to set floors on haircuts and margins on derivatives and SFT at the transaction level. Furthermore, they should be able to change these in a time-varying manner. The current margin and haircut-setting practices stimulate the build-up of leverage via these transactions in good times – when there is a tendency to under-price risk – and amplify deleveraging in bad times. While a number of policy measures aimed at limiting the pro-cyclical effects of margin and haircut-setting have already been adopted or are underway, none of these steps envisage their time-varying implementation by macroprudential authorities.

This new macroprudential framework could build on the current regulatory frameworks and policy recommendations as applicable to derivatives and SFTs at EU and global level. These frameworks include the FSB policy recommendations for haircuts on non-centrally cleared securities financing transactions, the BCBS-IOSCO margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives and the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR).

, Standardised margin and haircut schedules exist within these frameworks, and could form the basis for setting macroprudential margins and haircuts. For example, macroprudential authorities could build on the standardised FSB/BCBS-IOSCO haircut and margin schedules, which offer a transparent means of calculating initial margins as well as explicit numerical haircut values that can be set as floors to haircut and margin calculated with internal models.

Concluding remarks

Let me conclude. Europe needs to further integrate and develop its capital markets, and substantially so. In the absence of other cross-country risk-sharing mechanisms for the time being, this has a lot of promise for insuring European households and firms against national business cycle fluctuations. We need to be determined and ambitious in pursuing a Capital Markets Union that will deliver these benefits. This means to provide the conditions under which capital markets can flourish across the euro area and EU and at the same time, to design a regulatory and supervisory framework under which financial stability risks are under control. I am now looking forward to the upcoming discussion of the highlevel policy panel, that it will give us further food for thought on how to create a long-term vision for CMU, thus striking the right balance between the two dimensions I have discussed.

[1]See Obstfeld, M. and K. Rogoff, “Foundations of International Macroeconomics”, Harvard University Press, 1996.

[2]Asdrubali, P., B. Sorensen and O. Yosha , “Channels of interstate risk sharing: United States 1963-1990”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 111, 1996, pp. 1081-1110; Athanasoulis, S. and E. van Wincoop , “Risk sharing within the United States: What do financial markets and fiscal federalism accomplish?”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 83, 2001, pp. 688-698. See also Del Negro, M., “Asymmetric shocks among US States”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 56(2), March 2002, pp. 273-297.

[3]Hepp, R. and J. von Hagen, “Interstate risk sharing in Germany: 1970-1991”, Oxford Economic Papers 65, 2013, pp. 1-24.

[4]Fecht, F., H.P. Gruener, and P. Hartmann, “Welfare effects of financial integration”, CEPR Discussion Paper 6311, 2007.

[5]Balli, F. and B. Sorensen, “Risk sharing among OECD and EU countries: The role of capital gains, capital income, transfers, and savings”, MPRA Working Paper No 10223, 2007.

[6]Cumulative percentage contribution over a five-year period to the smoothing of a 1-standard deviation shock to GDP by fiscal tools: relative prices, credit markets and capital markets, as well as the portion that remains unsmoothed, for a 10-year rolling window between 1991 and 2015. Underlying data are from the annual macro-economic database of the European Commission (AMECO) and from the ECB’s Harmonized Competitiveness Indicators Database. ECB calculations.

[7]Fecht, F., H.P. Grüner and P. Hartmann (2012), “Financial Integration, Specialization, and Systemic Risk”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88(1), pp. 150-161. Fecht, F., and H.P. Grüner (2005), “Financial Integration and Systemic Risk”, CEPR discussion paper no. 5253.

[8]Keeley, M.C. (1990), “Deposit Insurance, Risk, and Market Power in Banking”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 80 (5), pp. 1183-1200.

[9]Aoki, K. and K. Nikolov (2015), “Financial Disintermediation and Financial Fragility”, CARF Working Paper, No CARF-F-374, November.

[10]ECB (2015), Report on financial structures, October.

[11]See the November 2015 edition of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review.

[12]Thurner S., J.D. Farmer and J. Geanakoplos (2012), “Leverage causes fat tails and clustered volatility”, Quantitative Finance, Vol. 12(5), pp. 695-707.

[13]Brunnermeier, M.K. and L.H. Pedersen (2008), “Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity”, The Review of Financial Studies Vol. 22(6), pp. 2201-2238.

[14]Brunnermeier, M.K. and L.H. Pedersen (2008), “Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity”, The Review of Financial Studies Vol. 22(6), pp. 2201-2238. Cifuentes, R., H.S. Shin and G. Ferrucci, (2005), “Liquidity Risk and Contagion”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 3(2-3), pp. 556-566.

[15]See the May 2015 edition of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review.

[16]Acharya, V.V. and T. Yorulmazer (2007), “Too many to fail – An analysis of time-inconsistency in bank closure policies”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vo. 16(1), pp. 1-31.

[17]Adrian, T. and M.K. Brunnermeier (forthcoming), “CoVaR”, American Economic Review.

[18]Brunnermeier, M.K. and L.H. Pedersen (2008), “Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity”, The Review of Financial Studies Vol. 22(6), pp. 2201-2238. See also the November 2015 edition of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review, and FSB (2015), Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report.

[19]Shek, J., I. Shim and H.S. Shin (2015), “Investor redemptions and fund manager sales of emerging market bonds: how are they related?”, BIS Working Papers No 509.

Banc Ceannais Eorpach

Stiúrthóireacht Cumarsáide

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, an Ghearmáin

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Ceadaítear atáirgeadh ar choinníoll go n-admhaítear an fhoinse.

An Oifig Preasa