Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to welcome you to Frankfurt for our annual non-standard measures workshop. We started this series of events five years ago to reflect on, and draw lessons from, central banks’ experience with what back then were considered exceptional types of monetary policy instruments. Five years on, those instruments have become less exceptional. Their variety has also grown. In response to the various stages of the financial crisis, the ensuing specific impairments of the monetary policy transmission mechanism, and the low inflation environment, the ECB has adopted several of these measures. Some, such as our very long-term refinancing operations (VLTROs), ensured the provision of liquidity to monetary and financial institutions over an extended period of time. Others, such as the SMP from 2010 and 2011, consisted in outright purchases of certain types of sovereign bonds.

The most recent non-standard measures introduced in June and September – two asset purchase programmes for asset backed securities (ABS) and covered bonds, and a programme to provide longer-term funding to banks for new loans – also fall under these two broad categories. A casual observer may therefore conclude that they represent just another variant of an established pattern. Today I wish to emphasise that this is not the case: the measures decided in the past few months mark a new phase in the ECB’s approach. With these new measures, the Governing Council demonstrates that we are ready to actively steer the size of our balance sheet towards significantly larger levels, so as to further ease the stance of monetary policy in a situation in which policy rates have reached their lower bound. Previous non-standard measures, in contrast, were mainly aimed at redressing impairments in the monetary policy transmission mechanism and meant to foster a regular pass-through of our monetary policy stance. Their implications for the ECB’s balance sheet had been accommodated in a merely passive way to satisfy the liquidity demand of our counterparties.

I will start my remarks today with some general considerations on the rationale for the design of our new non-standard measures and on the channels through which we expect them to get us closer to our inflation goal and to support the economic recovery. Our new non-standard measures signal the commitment of the Governing Council to meet our medium-term price stability mandate by maintaining a very accommodative monetary stance in the future. They furthermore aim to promote the flow of credit to the real economy.

After this overview, I will discuss in some detail the particular measures that we have introduced, focusing also on the potential challenges posed by their practical implementation. I will then conclude with an informal analysis of the market reactions to the announcement of those measures. I will maintain that market reactions have been significantly different from those following the announcement of previous non-standard measures. This suggests that markets have understood that this is a new phase in our approach.

General considerations underlying recent non-standard measures

The recovery in the euro area is still weak and fragile. The ECB’s staff macroeconomic projections in September predicted an output growth of 0.9% and a headline inflation rate of only 0.6% for the current year. Thereafter, the inflation rate is expected to increase gradually up to 1.4% in 2016, a level which is still below our price stability mandate defined as a rate of growth in the euro area HICP of below, but close to, 2%.

This period of very low inflation reflects a persistent shortfall in aggregate demand and raises serious concerns, as it tends to push real interest rates up, in spite of the very low key ECB interest rates.

A particular source of concern is that credit supply conditions in the euro area continue to be tight, despite some weak signs of improvement. [1] Small and medium-sized enterprises still consider access to finance an important problem, especially in countries under stress. [2] A key factor behind these developments is the ongoing balance sheet repair of euro area banks. This is a necessary process with clear long-term benefits. In the short-term however, bank deleveraging can create adverse aggregate demand externalities when monetary policy is constrained at the zero lower bound and the fiscal space is limited. [3]

In such an environment, the academic literature recommends “managing” expectations about the future path of interest rates. [4] A potential way to achieve this is by following what has been characterised by Campbell, Evans, Fisher and Justiniano (2012) as “Odyssean” forward guidance. The central bank explicitly commits to keeping interest rates low even after the recovery has taken hold, and thereby tolerates a temporary overshooting of its inflation objective.

However, the practical implementation of such measures is typically not discussed in the literature. The exact means by which private sector expectations could be managed are left unspecified. In the same vein, it is also unclear how the credibility of the central bank commitment would be ensured.

The Governing Council of the ECB has never considered such an extreme form of forward guidance. But it has successfully adopted a simpler version of that approach.

Certain forms of non-standard measures can also play a signalling role, i.e. help shape markets’ expectations about the future path of policy interest rates. An obvious example is that of refinancing operations at a pre-specified interest rate and whose maturity extends over many years. First, these operations provide an implicit signal of the central bank’s views about its intentions on future interest rates. And second, they can provide information on the central bank’s commitment to maintain an accommodative monetary policy stance in the future. The conference paper by Gauti Eggertsson and co-authors describes an explicit example of this channel.

Some of our new non-standard measures, notably a new type of longer-term refinancing operations, can be understood in this light. Other new non-standard measures aim to stimulate the economy directly, like our recently announced asset purchase programme for securities backed by private sector assets. From a general perspective, central bank asset purchases at market prices will tend to be welfare-improving, as they enhance growth prospects through several different channels.

The specific measures adopted by the ECB: TLTRO, ABSPP, CBPP3

Let me now illustrate how these general principles are reflected in the specific measures that we adopted in June this year.

In May, the inflation rate stood at 0.5%, far away from our objective of below but close to 2%. This worrying decline of monthly inflation rates, which had started in October 2013, led the ECB’s Governing Council to take a whole package of policy measures. We cut our policy rate by 10 basis points and allowed our deposit facility rate to go into negative territory to -10 basis points; we suspended the weekly liquidity absorption of our SMP programme; we extended until December 2016 at the very least, our extraordinary regime of providing liquidity at fixed-rate full allotment to banks in the regular operations; and we reinforced our forward guidance about future interest rates. Broadly speaking, these measures were mostly geared at the conventional interest rate channel by bringing down short-term rates.

We also adopted measures directed at the credit channel, such as extending to 2018, the acceptance of pools of small loans as collateral for monetary policy operations. Most importantly, we announced the Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations, or TLTROs, programme. The aim of the programme is to offer funding for banks over a prolonged period of time in exchange for new credit to non-financial corporations.

The TLTROs differ from our earlier one-year and three-year LTROs in many respects:

First, the new programme is designed to provide incentives for banks to channel the newly received central bank liquidity towards the creation of credit to non-financial corporations, including SMEs. The availability of TLTRO funding for up to four years for our counterparties is subject to specific conditions. The amounts counterparties can borrow during the first two operations in September and December are limited to the outstanding stock of credit to the non-financial private sector, excluding credit to households for home purchases. The second phase of the new facility, on a quarterly frequency until 2016, provides liquidity of up to three times the amount banks contribute to create positive net lending to the non-financial private sector. Banks that have been deleveraging have to keep credit above their trend of deleveraging during the first year and stop reducing credit afterwards in order to comply with the programme conditionality. In the absence of compliance, banks will have to repay their funds after two years, thus foregoing the benefit of cheaper funding during two more years.

A second key difference is that TLTROs have fixed rather than flexible rates. In particular, their rate is fixed at 10 basis points over the MRO rate prevailing at the time the TLTRO is stipulated. The TLTROs thereby ensure funding conditions for banks at a very low, given interest rate for a prolonged period of time (until the end of 2018), even if the MRO rate were to be increased during this time period. This property contributes to increase the signalling effect of the TLTRO announcements, compared with that of the previous LTROs, whose cost was linked to the MRO rate prevailing over the course of the programme.

Incidentally, a successful signalling effect reduces the expected value of the insurance provided by the TLTROs. If markets are convinced that an increase in the MRO rate over the life of the TLTROs is very unlikely, they would find it unnecessary to buy insurance against this event.

Independent of such considerations, the announcement of the programme has produced a beneficial effect by flattening interest rates along the term structure. Additionally, rather than hedging against future rate increases, we expect banks to use the facility to secure the benefit of cheap funding during four years.

While stigma effects might have prevented banks from taking up funding during the 2011/2012 VLTROs, such effects should be nil this time around: banks are currently not experiencing liquidity stress. Accordingly, the TLTROs thus continue to be the most important measure that can be relied on to gradually increase our monetary base.

A little more than a month after these measures were adopted, the situation deteriorated further. GDP figures for the second quarter of the year surprisingly indicated a stagnation of economic activity. This accentuated the risk that the effects of slack in the economy could become more prolonged and have a depressing effect on inflation. The rate of inflation fell to 0.4% and, more worryingly, inflation expectations started decreasing for all periods up to five years.

Central banks simply cannot run the risk of observing inflation expectations starting to become unanchored, given the challenges in controlling them ex-post. Consequently, the risk related to inflation expectations considerably influenced our decision in September, to add a new set of measures to complement and reinforce the package adopted in June.

In addition to cutting our key policy rates by another 10 basis point, we announced two asset purchases programmes: the asset backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP) and the covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3). We thereby conveyed our objective to control more directly the increase of the monetary base rather than merely depend on the banks’ behaviour in using our liquidity facilities. We showed our intention to use other channels of monetary transmission.

The first channel relates to expectations, which we reckon will respond to our determined policy of using our balance sheet in a more direct way. The second channel operates through portfolio effects, as the liquidity directly injected by our purchases can have spillover effects on all types of assets, from corporate bonds to foreign exchange. So, the effect of both programmes goes beyond their direct impact in reducing the interest rate spreads of the purchased assets.

Our purchases are not aimed at buying the securities mostly from banks. Nevertheless, in the present environment, direct purchases of private assets by the central bank can also support banks on the capital side. The broad effect that we expect to obtain in fostering growth will reduce the risk of firms’ defaulting and through this channel also help banks’ balance sheet repair, thus supporting credit flows.

The purchase of both types of assets – ABSs and covered bonds – will be subject to rigorous conditions and the appropriate risk management measures to protect our own balance sheet. Securities to be purchased will have to comply with the same conditions as those in use for acceptance as collateral in our monetary operations. This allows the Eurosystem to perform its own due diligence when assessing the credit risk of ABSs. These conditions imply, for instance, that only ABSs that have simple structures and real and transparent underlying assets can be purchased, and that more complex ABS are excluded. Minimum ratings are necessary in both cases. Besides, there are limits as regards the amount of each issue that can be bought or the amount per issuer.

Remarks have been made on the fact that we were not excluding Greek and Cypriot securities from the programme. However, an important condition for considering purchases of these securities is that these countries must be under a European programme. In addition, through risk mitigation measures, such as demanding overcollateralization and considerably limiting the amount of each issue that can be bought, we achieve risk equivalence with purchases from jurisdictions that have ratings above the minimum, a fact that has not been duly reported.

All these restrictions reduce the amount of both assets that can potentially be bought. In the case of covered bonds, only half of them are eligible: from a total of €1.2 trillion, the stock of covered bonds that comply with all our requirements is reduced to about €600 billion. The total existing stock of ABS corresponds to €690 billion of which around €400 billion qualify as purchasable assets. We will buy only senior ABS tranches and will consider buying mezzanine tranches only if they benefit from an appropriate government guarantee. Such guarantees would greatly enhance the impact of the ECB purchase programme. Government guarantees for mezzanine tranches of ABS would also represent a means to increase SME lending in a structural way, by enabling banks to establish a market-based funding mechanism for SME loans.

Notwithstanding these restrictions, the overall purchasable amount of ABSs and covered bonds is sufficient to ensure that asset purchases can be carried out on a large scale. We are, of course, aware that the amounts that we will be able to buy will be lower than the theoretical amount. After all, present holders, banks and non-banks must be willing to sell these securities – a willingness that relates to many factors, including their assessment of the risk/return prospects of alternative uses for the cash they would get.

Allow me one last remark on the overall management of risk related to ABS purchases: ABSs issued in Europe entail a much lower default rate than ABSs issued in the U.S. Average total losses of European AAA rated securitisations over the period 2000-2013 amounted to 0.2% of the notional, against 3.6% for the U.S. securitisations according to the rating agency Fitch. The discrepancy is even higher if the performance of non-AAA investment grade securitisations is considered: for the same period (2000-2013), the average losses for such European securitisations amounted to about 3.1%, while it reached 25% in the case of U.S. securitisations. And these average figures are for all types of ABSs, including complex ones that are no longer accepted in our operations. Average total losses would thus be much lower for high-quality ABSs, from which we will buy senior tranches.

For this reason, the ECB and the Bank of England have been trying to foster the European securitisation market by promoting the issuance of high-quality ABSs. The features of these high-quality securities match precisely those determining the eligibility of securities in our collateral policy and purchases. Contrary to some very vocal views, we are definitely not intending to buy junk securities with a high risk of default.

Some remarks on market reactions to the ECB’s announcements

It goes without saying that it is too early to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of the new programmes. All we know for the moment is that, in the first TLTRO auction in September, banks have obtained €83billion, an amount within the range of internal ECB forecasts and – judging from the lack of sizeable market reactions – apparently also consistent with the lower range of market expectations.

We can, however, already estimate the signalling effect of our new measures, by analysing the financial market impact of their announcement. I will do so using the so-called event study approach, which is fairly intuitive and useful to draw some tentative inference. Further analyses will of course be necessary to draw firmer conclusions.

With all due caveats, a clear difference emerges when comparing financial market reactions to the announcement of the recent measures with the announcements [5] of past LTROs and asset purchase programmes. Over a two-day window, past announcements led, on average, to a reduction in spreads between yields on different euro area assets, as reflected, for example in the differential between average euro area government yields and AAA yields. At the same time, past measures tended to have negligible effects on the level of AAA yields. This is consistent with an interpretation of past measures as being mainly aimed at redressing financial market impairments, a view shared by Annette Vissing-Jorgensen and co-authors (2013) in some of the conclusions of their conference paper. [6]

Different market reactions could however be observed after the ECB’s policy announcement in June 2014. That announcement actually contained many elements –from the new set of non-standard measures to an interest rate cut – and it is hard to disentangle the effects of all individual elements in a scientific manner.

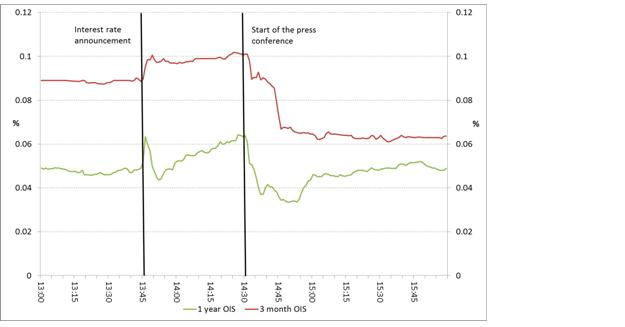

I would argue that many of those elements did not constitute big news, because they had already been, to some extent, discounted by financial markets. First, the decision to lower the key ECB interest rates by 10 basis points, setting a negative deposit rate for the first time was more or less expected, since the readiness of the Governing Council to adopt this decision had been explicitly communicated earlier. Our practice to announce our interest rate decisions at 1:45 p.m., before our regular press conference starting at 2:30 p.m., also helps to disentangle their impact from the effects of other measures announced during the day. Looking at the intraday development of prices of financial market instruments, which reflect market expectations of future interest rate developments, we find that the interest rate change was, if anything, smaller than expected (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Intraday development of 3 month and 1 year interest rate swaps (5 June 2014)

Second, the Governing Council’s intention to intensify the preparatory work for the ABS purchase programme was no big news, since the ongoing preparatory work had been public knowledge since at least the beginning of the year.

Third, the Governing Council announced that it would continue conducting the main refinancing operations through fixed-rate full allotment tenders for as long as necessary and at least until the end of 2016. This commitment should not have come as a surprise, after the implementation of the ECB’s forward guidance in June 2013.

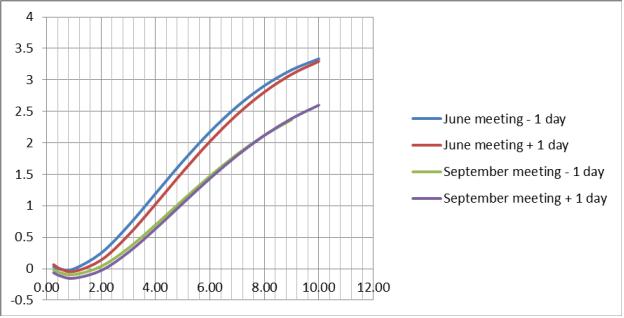

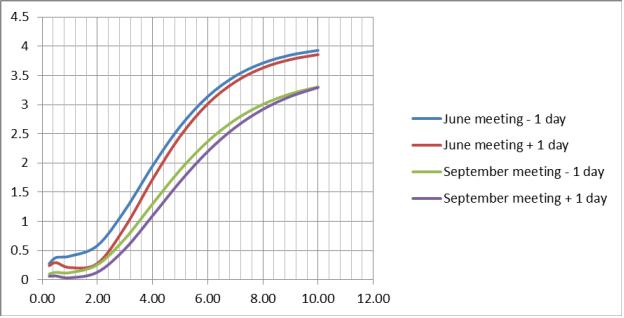

All in all, I would maintain that the main surprise component of the Governing Council’s decisions in June 2014 was the announcement of the new TLTRO programme, possibly complemented by the breadth of measures announced jointly to signal the ECB’s commitment to fight against the risk of a prolonged low-inflation period. The powerful signalling effect of the TLTRO announcement is clearly evident in the prominent downward shift of the forward yield curve of euro area AAA sovereign yields (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Forward yield curve of AAA euro area government bonds (3 months-10 years)

This is consistent with market expectations that the Governing Council would start raising key ECB interest rates later and at a slower pace than foreseen even one day before. The market expectations of both shorter- and longer-term inflation (as reflected in inflation swap rates) actually increased in response to the announcement (see Table 1).

Table 1: Financial market reactions on the two days around the Governing Council meetings

| June meeting | September meeting | |

| 3 month interest rate swap | -2.70 bps | -6.2 bps |

| AAA 10 year sovereign yield | -10.9 bps | -3.52 bps |

| Average 10 year EA sovereign | -16.16 bps | -12.53 bps |

| BBB 10 year corporate bond yields | -8.8 bps | -3.9 bps |

| Inflation linked swap 1x1 | 2.9 bps | 3 bps |

| Inflation linked swap5x5 | 1.25 bps | 1.8 bps |

| Exchange rate (USD/EUR) | -0.128% | 1.37% |

Calculated using observations at two days difference, i.e. (t+1) – (t-1) with t being the date of the decision.

In other words, the market came to price a decline in the path of real interest rates, which would stimulate demand and bring inflation closer to the ECB’s target.

The announcement had a particularly strong impact also on the shorter end of the forward yield curve of all euro area sovereigns (see Figure 3), leading to a substantial compression of sovereign spreads.

Figure 3: Forward yield curve of all euro area government bonds (3 month-10 years)

The impact is particularly powerful over the maximum four-year horizon of the TLTRO, suggesting that the market expects the programme to have a significant impact on yields of countries under stress. Substantial downward effects could also be observed on long-term corporate bond yields, while euro area stock market indices increased substantially. The initial impact was surprisingly muted on the nominal exchange rate.

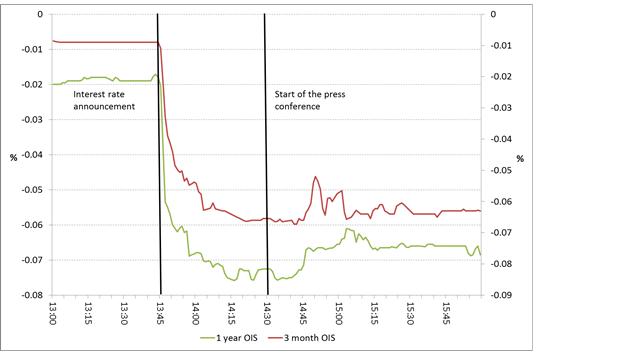

The September announcement of a further 10 basis points interest rate cut and of further details on the asset purchase programmes brought forward-rates further down, though the decline was somewhat more muted than after the June meeting. Most market reactions were observed just after our interest rate announcement, suggesting that the rate cut was considered the key news for the market during the day (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Intraday development of 3 month and 1 year interest rate swaps (4 September 2014)

Similarly to standard monetary policy shocks, [7] all yields nevertheless edged down, inflation expectations moved upwards, stock market indices increased, and the euro depreciated markedly.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The non-standard measures recently announced by the Governing Council of the ECB mark the beginning of a new phase. With these new measures, we wish to actively steer the size of our balance sheet towards significantly larger levels, so as to further ease the stance of monetary policy in a situation in which policy rates have reached their lower bound.

Initial financial market reactions suggest that the nature of our new measures has been appreciated: not only did financial spreads narrow, but also the whole forward-rates curve flattened upon their announcement.

We are confident that the new measures will help sustain the economic recovery in Europe. Nevertheless, as stressed in the introductory statement at our latest press conference: “Should it become necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation, the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to using additional unconventional instruments within its mandate”.

References

Bhattarai, S., G. B. Eggertsson, B. Gafarov, 2014, “Time Consistency and the Duration of Government Debt – A Signalling Theory of Quantitative Easing,” paper presented at the conference

Campbell, J., Ch. Evans, J. D. M. Fisher, and A. Justiniano, 2012, “Macroeconomic Effects of Federal Reserve Forward Guidance,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Eggertsson, G. and M. Woodford, 2002, “The Zero Bound of Interest Rate and Optimal Monetary Policy,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Farhi, E. and I. Werning, 2013, “A Theory of Macroprudential Policies in the Presence of Nominal Rigidities,” NBER WP 19313

Jardet, C. and A. Monks, 2014, “euro area Monetary Policy Shocks – Impact on Financial Asset Prices During the Crisis,” unpublished manuscript

Korinek, A. and A. Simsek, 2014, “Liquidity Trap and Excessive Leverage,” NBER WP 19970

Krishnamurthy, A., S. Nagel and A. Vissing-Jorgensen, 2014, “ECB Policies Involving Government Bond Purchases: Impact and Channels,” unpublished manuscript

Rogers, J. H., Ch. Scotti, and J. H. Wright, 2014, “Evaluating Asset-Market Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policies – A Cross Country Comparison,” FRB International Finance Discussion Paper 1101.

-

[1]See the Bank Lending Survey, July 2014.

-

[2]See, for example, Survey on the Access to Finance of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in the euro area, April 2014.

-

[3]See Korinek-Simsek, 2014 and Fahri-Werning, 2014.

-

[4]See Eggertsson and Woodford, 2003.

-

[5]We use the categorisation of Rogers et. al. (2014).

-

[6]A similar conclusion has been reached by Rogers et. al. (2014).

-

[7]For a high frequency analysis of monetary policy shocks in the euro area before and after 2007, see e.g. Monks and Jardet (2014)