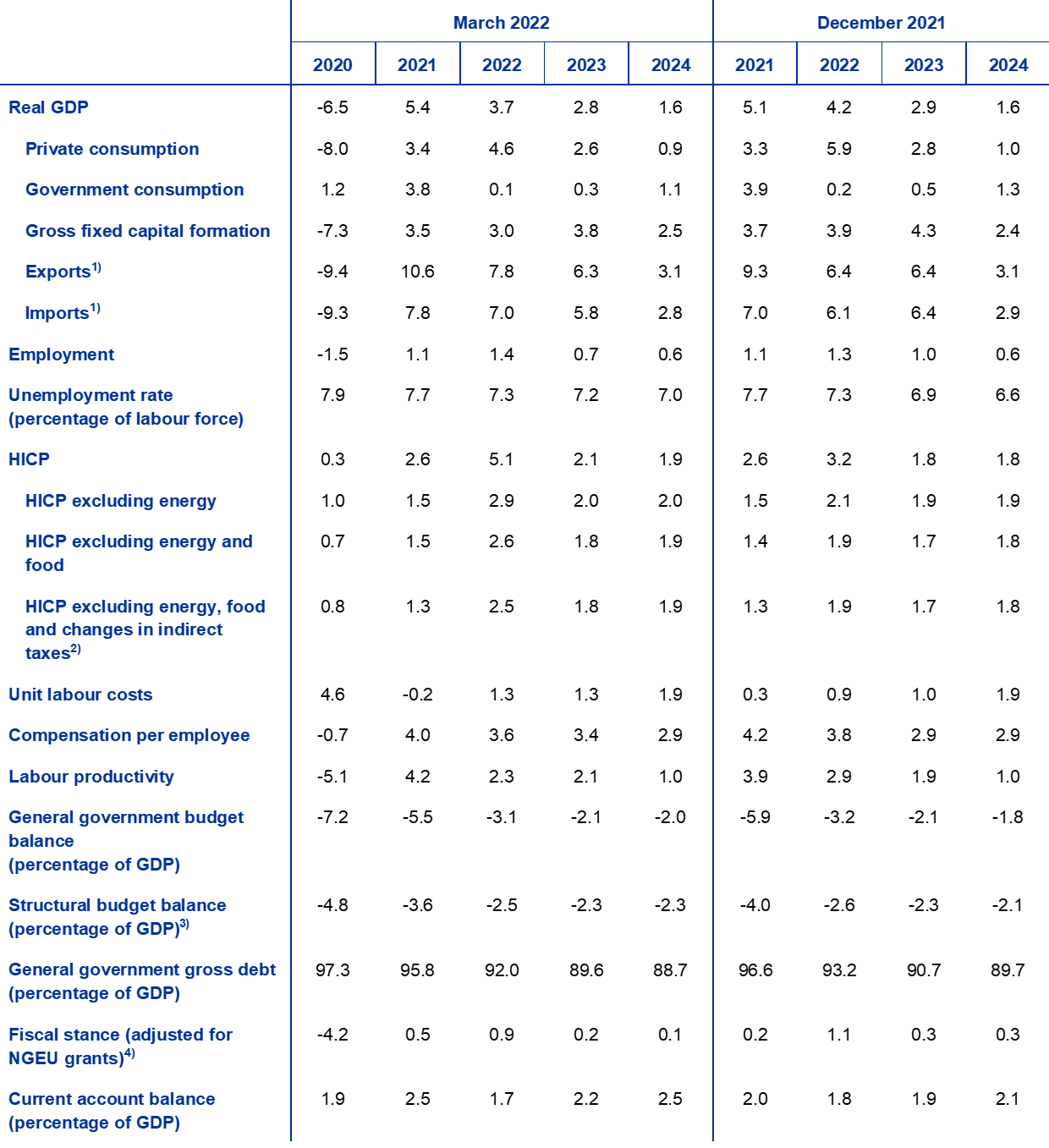

ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, March 2022

Overview

The outlook for euro area activity and inflation has become very uncertain and depends crucially on how the Russian war in Ukraine unfolds, on the impact of current sanctions and on possible further measures.[1] The baseline includes an initial assessment of the impact of the war on the euro area economy based on the information available up to 2 March 2022. Soaring energy prices and negative confidence effects imply significant headwinds to domestic demand in the near term, while the announced sanctions and sharp deterioration in the prospects for the Russian economy will weaken euro area trade growth. The baseline projections are built on the assumptions that current disruptions to energy supplies and negative impacts on confidence linked to the conflict are temporary and that global supply chains are not significantly affected. Based on these assumptions, the baseline projections foresee a significant negative impact on euro area growth in 2022, from the conflict. Nevertheless, given the starting point for the euro area economy, with a strong labour market and headwinds related to the pandemic and supply bottlenecks assumed to fade, economic activity is still projected to expand at a relatively strong pace in the coming quarters. Over the medium term, growth is projected to converge towards historical average rates, despite a less supportive fiscal stance and an increase in interest rates in line with the technical assumptions based on financial market expectations. Overall, real GDP growth is projected to average 3.7% in 2022, 2.8% in 2023 and 1.6% in 2024. Compared with the December 2021 Eurosystem staff projections, the outlook for growth has been revised down by 0.5 percentage points for 2022 owing mainly to the impact of the Ukraine crisis on energy prices, confidence and trade. This downward revision is partly offset by a positive carry-over effect from upward data revisions for 2021. Growth in 2023 has been revised down by 0.1 percentage points, while in 2024 it is unchanged.

Following a series of exceptional energy price shocks, the conflict in Ukraine implies that headline inflation in the baseline is projected to remain at very high levels in the coming months, before easing slowly towards target. It is set to average 5.1% in 2022, 2.1% in 2023 and 1.9% in 2024. Near-term price pressures have risen significantly, in particular those related to oil and gas commodities. These pressures are assessed to be more lasting than previously expected and to be only partly offset by dampening effects on growth from lower confidence and by weaker trade growth related to the conflict. Nevertheless, in the absence of further upward shocks to commodity prices, energy inflation is projected to drop significantly over the projection horizon. In the short term, this decline relates to base effects, while the technical assumptions based on futures prices embed a decline in oil and wholesale gas prices resulting in a negligible contribution from the energy component to headline inflation in 2024. HICP inflation excluding energy and food remains high in 2022, at 2.6%, reflecting stronger price dynamics for contact-intensive services, indirect effects from higher energy prices and upward impacts from ongoing supply bottlenecks. As these pressures ease, this measure of underlying inflation is expected to decrease to 1.8% in 2023 and then to rise to 1.9% in 2024, on account of strengthening demand, tightening labour markets and some second-round effects on wages, in line with historical regularities. Compared with the December 2021 Eurosystem staff projections, in cumulative terms over the projection horizon, headline inflation has been revised upwards substantially, especially in 2022. This upward revision reflects recent data surprises, higher energy commodity prices, more persistent upward pressures from supply disruptions and stronger wage growth, also related to the planned increase in the minimum wage in Germany. The upward revision also takes into account the recent return of survey-based indicators of medium-term inflation expectations to levels consistent with the ECB’s inflation target. These effects more than offset the negative impact on inflation of a significant upward revision to the market-based assumptions on interest rates and the negative demand-related effects of the conflict in Ukraine.

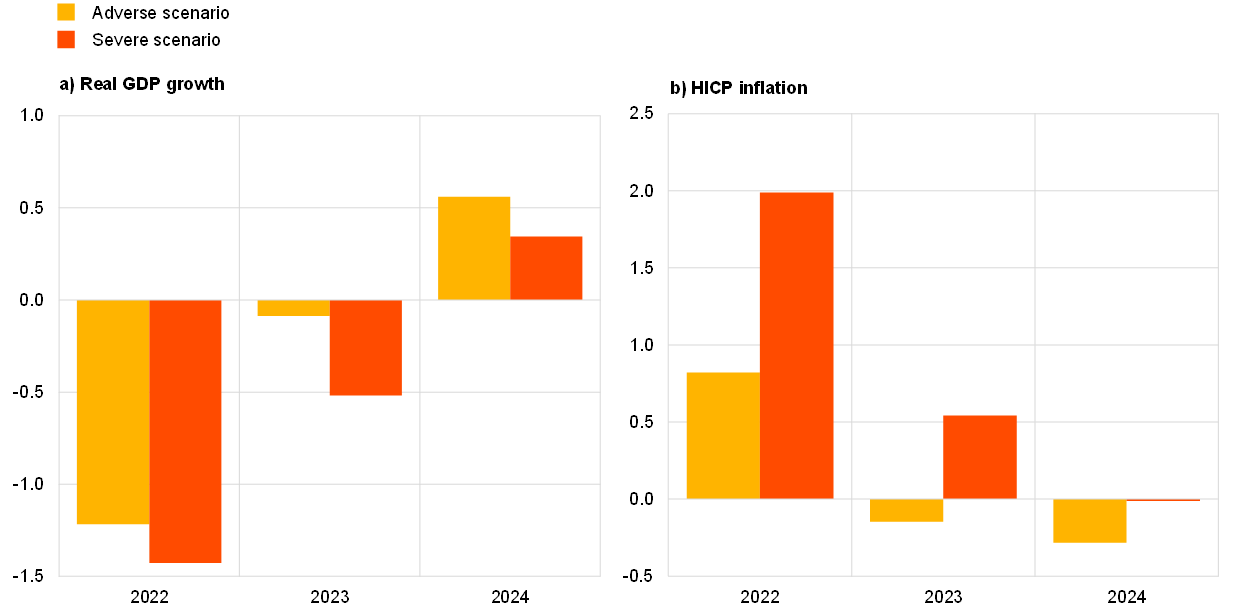

On account of the significant uncertainty surrounding the impact of the conflict in Ukraine on the euro area economy, in addition to the baseline, two scenarios have been prepared. Compared with the baseline, an “adverse” scenario assumes that stricter sanctions are imposed on Russia, leading to some disruptions in global value chains. Persistent cuts in Russian gas supplies would lead to higher energy costs and to cuts in euro area production, but this would be only temporary as substitution into other energy sources takes place. In addition, geopolitical tensions would be more sustained than in the baseline, leading to additional financial disruptions and more persistent uncertainty. Under such a scenario, euro area GDP growth would be 1.2 percentage points lower than the baseline in 2022, while inflation would be 0.8 percentage points higher. Differences would be more limited in 2023. In 2024, growth would be somewhat stronger than the baseline as the economy catches up after the larger negative impact on economic activity in 2022 and 2023. As oil and gas markets rebalance, the large spikes in energy prices would gradually unwind, causing inflation to decline below the baseline, especially in 2024. A more “severe” scenario includes, in addition to the features of the adverse scenario, a stronger reaction of energy prices to more stringent cuts in supply, stronger repricing in financial markets and larger second-round effects from rising energy prices. This scenario would imply GDP growth in 2022 that is 1.4 percentage points below the baseline, while inflation would be 2.0 percentage points higher. Significantly lower growth and higher inflation, compared with the baseline, would also be seen in 2023. Higher persistence of the disruptions triggered by the war imply that, in 2024, the catch-up effects on growth would be relatively modest whereas stronger second-round effects would offset the negative impact on inflation from declining energy prices.

Growth and inflation projections for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Notes: Real GDP figures refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

1 Real economy

Real GDP growth moderated to 0.3% in the fourth quarter of 2021 amid tightening supply bottlenecks, more stringent pandemic restrictions and higher energy prices, broadly in line with expectations in the December 2021 projections. Private consumption contracted as a result of rising infection rates and renewed pandemic uncertainty, coupled with a price-induced drop in real disposable income. In contrast, investment and public consumption provided positive contributions to growth, and economic activity returned to its pre-pandemic level.

Chart 1

Euro area real GDP growth

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, seasonally and working day-adjusted quarterly data)

Notes: Data are seasonally and working day-adjusted. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon.

Real GDP growth is expected to remain subdued in the first quarter of 2022 amid tighter mobility restrictions, persistent supply disruptions, high energy prices and the conflict in Ukraine (Chart 1). A drop in retail sales in December 2021 (down 2.7% from November) and a contraction in contact-intensive services due to tighter mobility restrictions at the turn of year translated into a negative carry-over effect for growth in the first quarter of 2022. This effect appears to have been partially compensated by a marginal monthly increase of retail sales in January 2022 (0.2%). More forward-looking indicators, such as the composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) and the European Commission’s Economic Sentiment Indicator, broadly remained in January and February at levels seen in the fourth quarter. Despite an improvement in the PMI for manufacturing supplier delivery times in January and February, the index continues to signal intense supply disruptions. However, the surveys on which these indicators are based were conducted before the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine. Taking the further energy shock and the uncertainty caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine also into account, real GDP growth for the first quarter of 2022 has been revised downwards by 0.2 percentage points compared to the December projections, and is now expected to be 0.2%.

The outlook for euro area activity has become very uncertain and crucially dependant on events in Ukraine. The war in Ukraine is weakening the near-term growth outlook mainly via trade, commodity prices and confidence channels. Sanctions and the economic drag on the Russian economy are weighing on euro area foreign demand, even though direct trade linkages with Russia are limited. Soaring energy prices and negative confidence effects, coupled with a deterioration in risk sentiment and declines in stock prices, imply subdued domestic demand. Nevertheless, our baseline projections assume that any disruption to energy supplies related to the conflict will be temporary and have no significant lasting impact on economic activity in the euro area. Box 3 provides more detail on the impact that the conflict is expected to have on the euro area economy and describes two alternative scenarios based on more negative assumptions.

Economic growth is still projected to pick up from the second quarter of 2022 as a number of headwinds start to fade, but this increase is tempered by the negative effects of the conflict in Ukraine. The expected improvement beyond the near term is based on a number of supporting factors: a diminishing economic impact from the pandemic, a gradual unwinding of supply bottlenecks and an improvement in export price competitiveness vis-à-vis key trading partners. In contrast, the conflict in Ukraine is expected to negatively affect euro area growth. Although the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme is expected to boost investment in some countries, the withdrawal of temporary government support measures implies that fiscal policy is expected to be less supportive, especially in 2022. Despite the increase in interest rates embedded in the technical assumptions, financing conditions will continue to be favourable. Overall, despite the downgraded outlook in the short term, real GDP is foreseen to broadly return to the path expected in the pre-pandemic projections (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Euro area real GDP

(chain-linked volumes, Q4 2019 = 100)

Notes: Data are seasonally and working day-adjusted. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections. The vertical line indicates the start of the current projection horizon.

Table 1

Macroeconomic projections for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Notes: Real GDP and components, unit labour costs, compensation per employee and labour productivity refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

1) This includes intra-euro area trade.

2) The sub-index is based on estimates of actual impacts of indirect taxes. This may differ from Eurostat data, which assume a full and immediate pass-through of indirect tax impacts to the HICP.

3) Calculated as the government balance net of transitory effects of the economic cycle and measures classified under the European System of Central Banks definition as temporary.

4) The fiscal policy stance is measured as the change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance net of government support to the financial sector. The figures shown are also adjusted for expected Next Generation EU (NGEU) grants on the revenue side. A negative figure implies a loosening of the fiscal stance.

Private consumption is projected to recover in the course of 2022, despite the increased uncertainty due to the conflict in Ukraine, and to remain the main driver of growth over the horizon. Against the backdrop of tighter pandemic-related restrictions – especially in contact-intensive services – and rising energy prices, private consumption contracted more than expected in the fourth quarter of 2021 and stood 2.5% below its pre-pandemic level. The higher energy prices weighing heavily on households’ purchasing power also implies a likely contraction in private consumption in the first quarter of 2022. Thereafter, private consumption is projected to increase, albeit more moderately than previously expected, reflecting some precautionary saving and further energy price rises due to the war in Ukraine. The pick-up in private consumption is based on the assumptions of a gradual resolution of the pandemic, an easing of supply constraints for consumer goods and only a temporary disruption to energy supplies as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. Consumption should continue to outstrip the path of real income in 2023 owing to a further unwinding of savings accumulated since early 2020.

Strong labour income is supporting growth in real disposable income, while higher inflation rates and the withdrawal of fiscal transfers are acting as a drag. Real disposable income is expected to decline strongly in the first quarter of 2022 on the back of higher inflation and lower net fiscal transfers. A rebound is foreseen from the second quarter of the year, shaped by improving labour markets and, to a lesser extent, other personal income, in line with moderate growth in economic activity. In contrast, net fiscal transfers are expected to weigh on income growth in 2022 as the number of people in job retention schemes decreases – with workers mostly transitioning back to regular employment – and other temporary pandemic-related fiscal measures expire. This is partly offset by new measures aimed at compensating for the impact of high energy prices. High inflation is dampening real disposable income more strongly than previously expected, thus contributing to its decline in 2022.

The household saving ratio is projected to decline to below its pre-crisis level, before stabilising towards the end of the projection horizon. The saving ratio is expected to fall throughout 2022, revised slightly downwards since the previous projections. While the conflict in Ukraine raises uncertainty, which would typically be expected to lead to an increase in precautionary savings, this effect is more than offset by households’ use of savings to cushion, at least partially, the negative effects of the energy shock on real consumption growth. The normalisation of consumers’ saving behaviour reflects the relaxation of containment measures and a dissipation of pandemic-related precautionary motives. The saving ratio is projected to broadly stabilise below its historical average level as of mid-2023. The persistent, albeit slight, undershooting of its historical average reflects the partial unwinding of excess household savings that have accumulated since the start of the pandemic. However, this effect is attenuated by the uncertainty caused by the events in Ukraine and by the concentration of excess savings in wealthier and older households with a lower propensity to consume, while households in the lower income groups remain more exposed to the energy price shock, also in the light of their lower buffers.[2]

Box 1

Technical assumptions about interest rates, commodity prices and exchange rates

Compared with the December 2021 projections, the technical assumptions include significantly higher oil and non-oil energy prices and higher interest rates. The technical assumptions about interest rates and commodity prices are based on market expectations with a cut-off date of 28 February 2022.[3] Short-term interest rates refer to the three-month EURIBOR, with market expectations derived from futures rates. The methodology gives an average level for these short-term interest rates of -0.4% in 2022, 0.3% in 2023 and 0.7% in 2024. Market expectations for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields imply an average annual level of 0.8% for 2022, gradually increasing over the projection horizon to 1.1% for 2024.[4] Compared with the December 2021 projections, market expectations for short-term interest rates have been revised up by around 10, 50 and 70 basis points for 2022, 2023 and 2024, respectively, on the back of expectations of a global tightening of monetary policy, supported by continued positive inflation surprises. This has also led to an upward revision of long-term sovereign bond yields, of around 50-60 basis points, over the projection horizon.

As regards commodity prices, the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil is assumed to rise from USD 71.1 on average in 2021 to USD 92.6 in 2022, before declining to USD 77.2 by 2024. This path implies that, in comparison with the December 2021 projections, oil prices in US dollars are almost 20% higher for 2022, 14% higher for 2023 and 11% higher for 2024, on the back of supply issues and the war in Ukraine. Since the cut-off date, energy prices have increased significantly. The impact of higher energy price assumptions than those included in the baseline projections are reflected in the scenarios presented in Box 3.

The prices of non-energy commodities in US dollars rose strongly in 2021 and are expected to rise more moderately in 2022 and to decrease slightly in 2023-24. EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) allowances are assumed, based on futures prices, to stand around €83 per tonne over the projection horizon – an upward revision of around 11% since the December 2021 projections.

Bilateral exchange rates are assumed to remain unchanged over the projection horizon at the average levels prevailing in the three working days ending on the cut-off date of 28 February 2022. This implies an average exchange rate of USD 1.12 per euro over the period 2022-24, which is around 1% lower than in the December 2021 projections. The assumption for the effective exchange rate of the euro implies an appreciation of 0.3% since the December 2021 projections.

Technical assumptions

Housing investment is expected to remain positive in the short term and to moderate over the rest of the projection horizon. Housing investment increased slightly in the fourth quarter of 2021, broadly in line with expectations in the December 2021 projections, with shortages of both labour and raw materials weighing on housing market activity. Despite the war in Ukraine, housing investment is projected to continue to grow in the short term against a backdrop of still notable demand – supported particularly by strong demand from higher-income households – and some tentative signs of easing supply constraints. After a short catch-up phase, in which supply constraints are expected to ease more noticeably, growth in housing investment should moderate over the rest of the projection horizon. Nevertheless, it will continue to be supported by positive Tobin’s Q effects and rising disposable income, while financing conditions will become somewhat less favourable.

Business investment is expected to increase over the projection horizon and to account for an increasing share of real GDP, despite the conflict in Ukraine, as supply bottlenecks ease and NGEU funds are disbursed. After the temporary drop in business investment observed in the third quarter of 2021, mostly caused by supply-side bottlenecks, business investment is estimated to have returned to more dynamic growth in the last quarter of 2021. In the short term, despite the increased uncertainty and financial market volatility due to the conflict in Ukraine, still high business confidence and capacity utilisation, as well as a better assessment of capital goods producers’ order books, point to sustained positive growth. As the supply disruptions ease, investment is expected to maintain a dynamic growth path, although the commodity price increases, negative confidence effects and trade disruptions related to the conflict are likely to act as a drag. The positive impact of the NGEU programme and projected profit growth in 2022 and beyond are also expected to provide support to business investment over the projection horizon. In addition, higher expenditures related to the decarbonisation of the European economy will provide an additional boost to business investment in the medium term. As a result, business investment should account for an increasing share of real GDP over the projection horizon.

Box 2

The international environment

The global economy remains on a robust growth path, although the conflict in Ukraine and, to a lesser extent, the spread of the Omicron coronavirus variant cloud the outlook. At the turn of the year, the spread of the new Omicron variant caused an unprecedented increase in the number of coronavirus (COVID-19) infections worldwide. As available evidence suggests that the Omicron wave will be shorter than previous waves, the impact on the global economy is expected to be rather moderate and limited to the first quarter of 2022. At the same time, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is weighing on the global economy. The imposition of substantial financial and trade sanctions on Russia has led to a significant downgrading of the country’s growth outlook over the projection horizon (see Box 3). In addition to being channelled by trade linkages, knock-on effects are being felt by other countries through higher energy prices, thus further reducing households’ disposable incomes, and negative confidence effects, which will weigh on domestic demand and trade.

Supply bottlenecks remain a headwind to growth, but recent indicators tentatively suggest some moderate easing since the end of 2021. Global PMI suppliers’ delivery times have been improving slightly but remain fairly tight by historical standards and are still long, while ocean shipping congestion remains high. At the same time, given the strong growth in goods trade and car production in recent months, it appears that supply constraints in some sectors may have passed their peak. Overall, supply bottlenecks are assumed to ease gradually in the course of 2022 and to have fully unwound by 2023 as consumer demand switches back from goods to services and shipping capacity and the supply of semiconductors increase on the back of planned investment. Nevertheless, there are risks – especially in the short term – that supply disruptions might intensify again. This could be the case if China sticks to its zero-COVID policy with the more infectious Omicron variant. Moreover, the war in Ukraine could cause bottlenecks to worsen, leading to shortages of commodities and critical raw materials, but also impediments in logistics and transportation in view of flight and shipping bans affecting trade across the region.

Over the medium term, the global economy is projected to continue its expansionary path, albeit at more moderate rates, amid geopolitical tensions and the unwinding of the pandemic-related policy stimulus. In 2021 global growth was underpinned by continued policy support. However, since the December 2021 projections, growth has been revised upwards owing to a better than expected outturn in the second half of the year, especially in large economies such as China and the United States. From 2022 onwards, global real GDP (excluding the euro area) is projected to converge to more moderate growth rates. Besides the impact of the Omicron variant and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, private consumption is expected to remain subdued amid rising inflation. Further ahead, “speed limit” effects are expected on account of tighter labour market conditions, which will be partly counterbalanced by the expected dissipation of supply bottlenecks. Diminishing policy support is also projected to limit growth over the projection horizon. Faced with strong inflationary pressures, central banks in some emerging market economies started to unwind their pandemic-related stimulus in 2021. In 2022, monetary policy accommodation is already being – or is soon expected to be – withdrawn also across advanced economies. Since December 2021 the Bank of England has raised interest rates twice and, in the United States, the Federal Open Market Committee has signalled a shift in its policy stance, hinting at a faster pace of normalisation in US monetary policy than previously expected. Growth is therefore projected to decelerate in the United States, also on account of a smaller than previously assumed fiscal stimulus. Among emerging market economies, growth is projected to slow in Brazil, owing mainly to aggressive monetary policy tightening amid rising inflationary pressures, and Turkey, which has experienced market turmoil related to high policy uncertainty and very high inflation, adversely affecting consumption and investment. While the emergence of new, more aggressive coronavirus variants cannot be ruled out, the influence of the pandemic on the global outlook is assumed to be gradually diminishing. Compared with the December 2021 projections, real GDP growth has been revised down over the projection horizon (-0.4 percentage points for 2022, -0.3 percentage points for 2023 and -0.1 percentage points for 2024). In the short term, the adverse impact of the above-mentioned factors is partly offset by a positive carry-over effect, while further into the projection horizon the downward revision relates to weaker growth in the United States and Russia, as well as in some other large emerging market economies.

After buoyant growth in 2021, growth in euro area foreign demand is projected to normalise gradually over the projection horizon. In the second half of 2021 global trade turned out stronger than expected, notwithstanding supply chain disruptions, driven by robust developments in emerging Asia (mainly China and India) and, in the fourth quarter, the United States. Survey data point to rather subdued trade growth at the turn of the year, partly on account of the resurgence of the pandemic, but this is expected to be temporary. For 2022, a positive carry-over effect more than offsets the weaker dynamics stemming from the revisions to global activity and the adverse effects of the conflict in Ukraine, which results in a significant upward revision to growth in global imports for 2022 compared with the December 2021 projections. Euro area foreign demand is unrevised for 2022, since the strong positive carry-over effect is fully offset by weaker trade on account of the conflict in Ukraine, while it is revised down for 2023 and 2024 (-1.1 percentage points and -0.3 percentage points respectively).

The international environment

(annual percentage changes)

1) Calculated as a weighted average of imports.

2) Calculated as a weighted average of imports of euro area trading partners.

The conflict in Ukraine is slowing the recovery in trade in the short term, although momentum is expected to strengthen later in 2022. Following signs of recovery in euro area foreign demand at the end of 2021, the war in Ukraine is denting the near-term prospect for euro area exports. Some gains in price competitiveness and the expected recovery in services trade should partly offset the headwinds related to the conflict. As a result, quarterly growth rates in euro area exports have been revised down in 2022. Nevertheless, the annual growth rate has been revised upwards, on the back of positive carry-over effects from upward revisions in the second half of 2021. On the import side, a short-term dampening of euro area activity dynamics is likely to result in lower growth rates. Net exports are therefore expected to contribute only mildly to GDP growth in 2022. The short-term outlook nevertheless remains clouded by significant downside risks related to supply chains disruptions caused by shortages of key inputs from Russia. If the effects of the conflict, supply constraints and pandemic-related restrictions unwind, starting in the second half of 2022, euro area trade will return to its long-term growth path. Strong increases characterise trade deflators following the energy price shock, especially on the import side, and will persist throughout 2022. These are also likely to entail a large deterioration in euro area terms of trade and the trade balance, which are expected to normalise only from 2023.

The labour market continues to strengthen. Employment grew by 0.5% in the fourth quarter of 2021, with a further decline in the unemployment rate. Employment is projected to grow further over the projection horizon despite some downward pressures from the increased uncertainty due to the war in Ukraine. In addition, the unemployment rate is likely going to be adversely affected in the short term, but in annual average terms it is projected to decline to 7.0% by 2024. This decline is driven mainly by the projected strong labour demand in line with the ongoing economic recovery.

Labour productivity growth is projected to decline gradually over the projection horizon towards its long-term average. After a temporary dip related to the deceleration in economic activity, labour productivity is expected to regain momentum as a result of stronger economic growth and to normalise gradually thereafter towards its long-term pre-pandemic average. By the end of the projection horizon, labour productivity (per person employed) is expected to be around 4.6% above its pre-crisis level.

Compared with the December 2021 projections, real GDP growth has been revised down by 0.5 percentage points for 2022 and by 0.1 percentage points for 2023, and is unrevised for 2024. The downgraded outlook for 2022 largely reflects the impact of the Ukraine crisis on energy prices, confidence and trade, and is partly offset by a positive carry-over effect from upward data revisions for 2021. In 2023 and 2024, upward impacts from price competitiveness gains related to higher cost pressures in some key trading partners are broadly offset by higher interest rate assumptions and a negative impact of higher energy prices.

Box 3

The impact of the conflict in Ukraine on the euro area economy in the baseline and two alternative scenarios

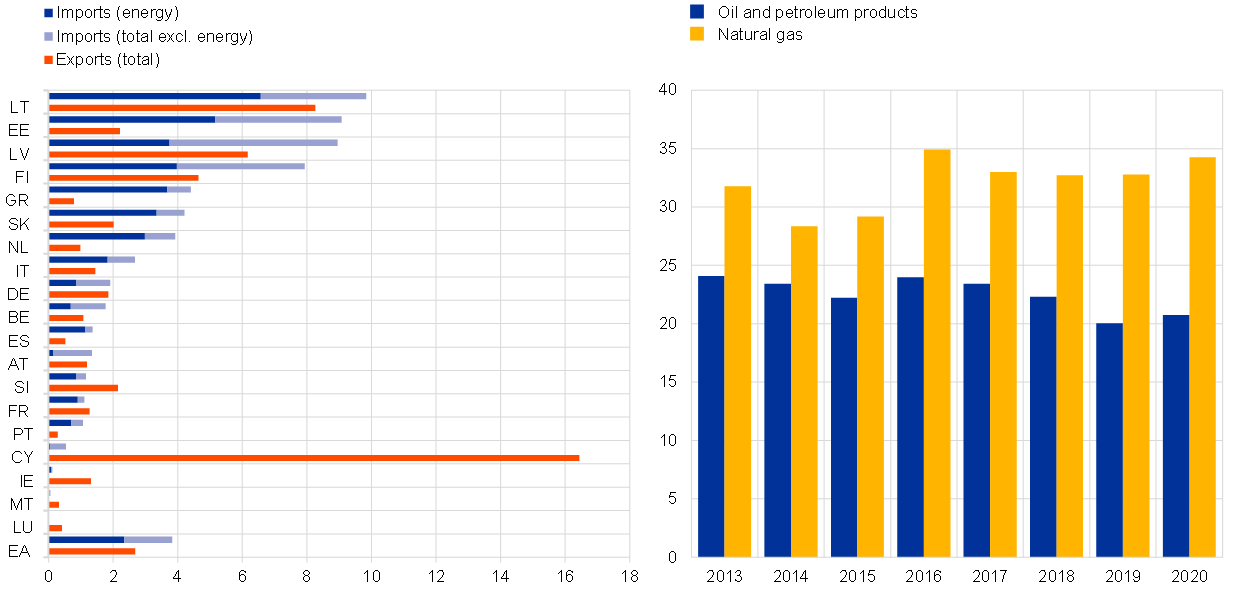

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is expected to significantly affect the euro area economy through three main channels: trade, commodities, and confidence. First, trade with Russia is affected by bans on imports and exports, as well as the adverse effects of the war on the Russian economy. The exclusion of Russian banks from SWIFT impairs trade financing of Russian firms, translating into extensive trade disruptions. In addition, a combination of higher interest rates, capital outflows, financing constraints, deterioration of business sentiment, rising import prices and rouble depreciation is weighing on Russian GDP. While the direct impact on the euro area economy is limited, with Russia accounting for a small share of euro area foreign demand (around 3%; Chart A, left-hand panel), the spillovers to the global economy – notably via countries with stronger trade links with Russia, such as those in central and eastern Europe – weaken the external outlook for the euro area more broadly. Second, the outbreak of the conflict has put significant upward pressure on commodity prices – already affected by the growing geopolitical tensions in the course of 2021 – beyond that already embedded in the baseline of the March 2022 projections. The impact on the euro area is sizeable, as Russia is its main energy provider, accounting for 20% of its oil and 35% of its gas in 2020 (Chart A, right-hand panel). While energy sector sanctions have so far been imposed only by non-euro area countries, consumers are increasingly reluctant to buy Russian oil, major companies are divesting Russian oil assets, and banks and insurance companies are increasingly unwilling to finance and insure Russian commodities trade. Finally, the war in Ukraine is eroding global confidence, which in turn is increasing volatility and risk premia in global financial markets. This worsening of financial conditions for euro area firms, together with sustained geopolitical tensions and uncertainty, is expected to affect investment.

Chart A

Euro area trade with Russia (left-hand panel) and euro area dependence on Russian energy supplies (right-hand panel)

(left-hand panel: percentage of total trade in goods and services; right-hand panel: percentage of imports)

Sources: ECB, Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Imports of natural gas include those of liquefied natural gas.

The high uncertainty surrounding the effects of the war in Ukraine on the euro area economic outlook warrants additional scenario analysis. The baseline projections are built on the assumptions that current disruptions to energy supplies and negative impacts on confidence linked to the conflict are temporary and that global supply chains are not significantly affected. Combined with the sanctions and the deterioration in global risk sentiment, an energy supply disruption is estimated to weigh on euro area real GDP growth in 2022 and to hamper activity still in 2023, before a small upward impact in 2024 on account of catch-up effects. As regards HICP inflation, the impact of the conflict on the baseline of the March 2022 projections is expected to be upward in 2022 on the back of rising commodity prices but, as the effect progressively fades away, to be muted in the outer years. This view is based, however, on the assumption that the war in Ukraine does not escalate significantly further and that existing sanctions against Russia remain in place over the full projection horizon. Two scenarios (an “adverse” scenario and a “severe” scenario) have been constructed, differing according to sanctions, trade, confidence and energy supply disruptions, but also to the implications of financial disruptions and likely reactions. The effects on the euro area are estimated through model-based simulations.[5] It should be noted that in both alternative scenarios it is assumed that the impact of the conflict will be most pronounced in 2022 and that there will be a resolution of the conflict over time. In this respect, more negative scenarios could be designed.[6]

Compared with the March 2022 projections, the adverse scenario assumes a worsening in all three channels (trade, commodities and confidence) and, in particular, constraints in the production capacity of the euro area. On the trade channel, more stringent sanctions entail a more severe drag on the Russian economy. These sanctions also create broad supply constraints and disruptions to global value chains. On the commodity prices channel, the scenario assumes a complete and lengthy cut-off of Russian gas to Europe, which the euro area is only able to partly compensate for by using other energy sources and through liquified natural gas substitution. Such a supply shortfall pushes gas prices sharply higher. Similarly, oil supply from Russia is severely disrupted, also pushing prices up. In addition, the interruption of gas supplies is assumed to trigger cuts in sectoral production across the euro area. Besides the energy sector, whose production is directly affected, other sectors relying heavily either directly or indirectly on gas (e.g. transportation, mining and quarrying, and chemical products) would be adversely affected as the shock propagates and amplifies down the supply chain.[7] Over time, the gas market is assumed to rebalance, leading to a gradual decline in gas prices and a resumption of production. On the confidence channel, stricter sanctions and more sustained geopolitical tensions than those embedded in the baseline lead to a more severe and protracted rise in global uncertainty and additional financial disruptions that affect some asset categories more persistently. This in turn further depresses risky asset prices and increases volatility. Finally, this scenario adds moderate financial amplification effects owing to a general increase in risk premia, leading to higher external financing costs for euro area firms and weighing on investment.

In addition to the assumptions encapsulated in the adverse scenario, the severe scenario entails a steeper and more persistent rise in commodity prices, triggering second-round effects from higher inflation and broader financial amplification effects. In the severe scenario, gas prices are assumed to be twice as sensitive to Russian gas supplies being cut off as in the adverse scenario, given the drawdown of inventory stocks and a continued tight gas market. This entails more severe upward price pressures, which are also expected to be somewhat more persistent because Russian gas is assumed not to be entirely substitutable over the projection horizon. As a result, the gas market rebalances at more elevated price levels. There is also a sharper increase in oil prices and a higher subsequent price level. On the confidence channel, this scenario assumes larger financial amplification effects, with a shock three times the magnitude of that assumed in the adverse scenario. Finally, this scenario includes larger second-round effects in the context of an overall higher inflation environment.

The overall impact for the euro area is significantly negative on real GDP growth, with a larger and more persistent effect under the severe scenario (Table and Chart B). In the adverse scenario, weaker foreign demand, higher commodity prices, heightened uncertainty, repricing in financial markets and production cuts lower real GDP growth by around 1.2 percentage points in 2022 and 0.1 percentage points in 2023 compared with the baseline. In 2024, growth is 0.5 percentage points higher than the baseline as the economy catches up after the larger negative impact on economic activity in 2022 and 2023. In the severe scenario, besides the mechanisms at play under the adverse scenario, the higher energy prices, along with a further increase in spreads on financial markets, lead to significantly lower real GDP growth compared with the baseline (-1.4 percentage points in 2022 and -0.5 percentage points in 2023). In 2023, the more persistent disruptions related to the war imply that the catch-up effects on growth would be limited, with growth 0.3 percentage points higher in 2024.

Table

Alternative macroeconomic scenarios for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Inflation would reach very high levels, on average, in 2022 under both scenarios but decrease progressively thereafter to stand in 2024 below the baseline of 1.9% in the adverse scenario and at the baseline level in the severe scenario (Table and Chart B). Assumptions about energy prices are the dominant driver for HICP inflation. The higher sensitivity of energy prices to supply cuts and the fewer offsetting factors under the severe scenario lead to a higher and more prolonged surge in HICP inflation. As such, the inflationary effects due to higher commodity prices amount to 0.8 percentage points in 2022 in the adverse scenario and to 2.0 percentage points in the severe scenario. In 2023, the upward pressures persist in the severe scenario, with HICP inflation 0.6 percentage points higher than the baseline. As oil and gas markets rebalance, the large spikes in energy prices gradually unwind, leading, with weaker euro area activity, to lower inflation. In the severe scenario, more elevated energy prices as well as stronger second-round effects take HICP inflation back to the baseline rate of 1.9% in 2024.

Chart B

Impact of alternative scenarios on real GDP growth and HICP inflation in the euro area compared with the baseline

(deviations from the March 2022 baseline projections, in percentage points)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

However, these scenarios abstract from a number of factors that may also influence the magnitude and the persistence of the impact. In particular, these scenarios have been prepared under the same fiscal assumptions as those of the March 2022 projections. As in 2021, governments may take action to cushion the impact of large energy prices hikes on consumers and firms. In addition, the estimated impact of gas supply interruptions on production does not consider substitution, which could lead to an effect that is not as strong as assumed in the scenario. On the other hand, an escalated and more protracted conflict entails the risk of a more pronounced and persistent impact. In addition, besides the energy price hikes included in the scenarios, other commodity prices such as food prices and some selected metal prices might also be severely affected by the conflict given the role of Russia and Ukraine in global supplies of these commodities.

2 Fiscal outlook

Some further fiscal stimulus measures have been incorporated into the baseline since the December 2021 projections. After the strong expansion in 2020, the euro area fiscal stance adjusted for NGEU grants is estimated to have tightened in 2021. This is mostly on account of revenue “windfalls” and other factors, which often manifest during a recovery. The fiscal stance is currently projected to tighten further in 2022, on account of the reversal of a significant part of the pandemic emergency support, and to a much lesser extent over the rest of the projection horizon. Compared with the December 2021 projections, the fiscal stance is expected to be around 0.2 percentage points of GDP looser in 2022 and broadly unchanged over 2023-24. For 2022, the revisions reflect, among other things, additional stimulus measures adopted by governments in response to the Omicron wave and new measures to compensate for higher energy prices, as well as a partial reversal of revenue windfalls from 2021. This additional fiscal impulse is partly compensated for by more subdued growth in expenditure, particularly government consumption and transfers. Fiscal assumptions and projections are currently surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty related to the war in Ukraine, with the risks assessed to be tilted towards the introduction of additional stimulus.

The euro area budget balance is still projected to improve steadily in the period to 2024, but by less than foreseen in the December 2021 projections. The euro area budget deficit is estimated to have remained high in 2021, having peaked in 2020. Over the projection horizon the substantial improvement in the budget balance is seen to be driven mainly by the cyclical component and the lower cyclically adjusted primary deficit. At the end of the horizon the budget balance is projected to be -2% of GDP and thus to remain below the pre-crisis level. After the sharp increase in 2020, euro area aggregate government debt is expected to decline over the entire projection horizon, reaching about 89% of GDP in 2024, which is above its pre-pandemic level. The decline is seen to be mainly due to favourable interest rate-growth differentials, but also to deficit-debt adjustments, which together more than offset the persisting, albeit decreasing, primary deficits. Compared with the December 2021 projections, the estimated budget balance outcome for 2021 has been revised significantly upwards, reflecting both a higher revenue-to-GDP ratio and a lower expenditure-to-GDP ratio. Despite the higher starting point, the budget balance in 2024 is now projected to be lower than foreseen in December, following the deterioration in the macroeconomic outlook triggered by the war in Ukraine and the upward revisions to interest payments as a share of GDP. The path of the euro area aggregate debt ratio has been revised downwards over the entire projection horizon, mainly on account of favourable base effects from 2021.

3 Prices and costs

Headline inflation reached 5.8% in February 2022 and is projected to remain elevated over the coming quarters (Chart 3). Inflation is being driven mainly by energy inflation, which rose to around 32% in February, mostly on account of higher gas and electricity tariffs. These two components are also expected to sustain energy inflation at high rates over the course of the year. By contrast, the contribution from fuels is expected to fade away in 2022 owing to base effects and an assumed downward-sloping profile of oil prices. Electricity and gas tariffs recorded a large month-on-month increase in January, with prices being reset for the new year in many countries, and further increases are expected in the course of the year as the surge in wholesale gas futures prices caused by the war in Ukraine is gradually passed on to consumers (although base effects imply some declines in annual inflation rates later in the year). HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to be 2.6% in 2022, owing to high demand, indirect effects from higher energy prices and price pressures along the pricing chain related to supply bottlenecks. Food inflation increased to 4.1% in February and is expected to remain high throughout 2022, owing to high commodity prices and extraordinary increases in gas and electricity prices, which account for around 90% of the total energy costs of the processed food industry and are an important factor for the production of fertilisers. Headline inflation is expected to decline in the second half of the year on the back of large negative base effects and an assumed downward-sloping profile of oil prices.

HICP inflation is expected to decline from an average of 5.1% in 2022 to 2.1% in 2023 and 1.9% in 2024. This decline in headline inflation over the projection horizon reflects sharp declines in energy inflation in line with the assumption that oil and gas prices will follow the downward-sloping profile of their respective futures curves despite some upward impact from i) the reversal in 2023 of temporary fiscal measures to reduce energy prices, ii) national climate change measures in 2023-24, and iii) lagged effects of earlier strong increases in wholesale gas prices. Food inflation is also expected to decrease over the projection horizon. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is projected to ease somewhat to stand at 1.8% in 2023, and then to increase to 1.9% in 2024. The initial easing results from the unwinding of upward impacts from supply bottlenecks as they are resolved and from the effects of the reopening of the economy, as well as base effects. While the adverse impact on growth from the war in Ukraine might have some dampening effects, these are likely to be offset by indirect effects from the higher energy prices triggered by the conflict. The slight increase in 2024 is in line with a tightening of product and labour markets, some second-round effects on wages from the inflation spike in 2021 and 2022, as well as longer-term inflation expectations being anchored at the ECB’s inflation target of 2%. The baseline projections are surrounded by significant uncertainty on account of the war in Ukraine, especially given the strong further increases in energy prices since the underlying technical assumptions were finalised. The alternative scenarios presented in Box 3 embed high energy prices.

Growth in compensation per employee is projected to be 3.6% in 2022 and to decline to 2.9% in 2024, remaining above the historical average recorded since 1999 (2.2%). Although compensation per employee, which was greatly distorted by policy measures in 2021, is envisaged to decrease somewhat, unit labour costs are expected to increase, driven by lower growth in productivity per person employed. The above average wage growth reflects the tightening labour market, the expected increase in the minimum wage in Germany in October 2022 and some second-round effects from the high rates of inflation.

Chart 3

Euro area HICP

(annual percentage changes)

Note: The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon.

External price pressures are expected to be significantly stronger than domestic price pressures in 2022 but to drop to considerably lower levels in the later years of the projection horizon. The annual growth rate of the import deflator is expected to be 8.2% in 2022, largely reflecting increases in oil and non-energy commodity prices but also some increases in input costs related to supply shortages. As of 2023, import price growth is expected to moderate and to stand at 0.7% in 2024.

Compared with the December 2021 projections, the outlook for HICP inflation has been revised up by 1.9 percentage points for 2022, 0.3 percentage points for 2023 and 0.1 percentage points for 2024. Three-quarters of the cumulative revision relates to the volatile energy and food components, while the remaining one-quarter relates to the projection for HICP inflation excluding energy and food. These revisions reflect recent upward data surprises, stronger and more persistent upward pressures from energy prices (stemming from the conflict in Ukraine) and supply disruptions, and stronger wage growth, also related to the planned increase in the minimum wage in Germany. The upward revision also took into account the recent return of survey-based indicators of medium-term inflation expectations to levels consistent with the ECB’s inflation target. In the outer years of the projections, these effects more than offset the negative impact on inflation of a significant upward revision to the market-based assumptions on interest rates and the negative demand-related effects of the conflict in Ukraine.

Box 4

Forecasts by other institutions

A number of forecasts for the euro area are available from both international organisations and private sector institutions. However, these forecasts are not directly comparable with one another or with the ECB staff macroeconomic projections, as these were finalised at different points in time. Importantly, none of the comparator forecasts currently include the impact of the war in Ukraine. Additionally, these projections use different methods to derive assumptions for fiscal, financial and external variables, including oil and other commodity prices. Finally, there are differences in working day adjustment methods across different forecasts (see the table).

Comparison of recent forecasts for euro area real GDP growth and HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: MJEconomics for the Euro Zone Barometer, 24 February 2022, data for 2024 are taken from the January 2022 survey; European Commission Winter 2022 Economic Forecast (Interim), 10 February 2022; Consensus Economics Forecasts, 10 February 2022, data for 2024 are taken from the January 2022 survey; ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters, for the first quarter of 2022, conducted between 7 and 13 January; IMF World Economic Outlook Update, 25 January 2022; OECD December 2021 Economic Outlook 110.

Notes: The ECB staff macroeconomic projections report working day-adjusted annual growth rates, whereas the European Commission and the IMF report annual growth rates that are not adjusted for the number of working days per annum. Other forecasts do not specify whether they report working day-adjusted or non-working day-adjusted data. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the cut-off date for the projections.

The March 2022 ECB staff projections are below those of other forecasters for growth in 2022, while for inflation in 2022 they are well above other forecasts, owing to the inclusion of the impact of the conflict in Ukraine and more recent data. For the outer years of the horizon, the differences are more limited. Despite the downward revision compared with the December 2021 Eurosystem staff projection for growth in 2022, the March 2022 ECB staff projection is only slightly below other more recent projections for 2022 and is still somewhat above other forecasts for 2023. As regards inflation, the ECB staff projection is far higher than the other forecasts for 2022 owing to the more recent cut-off date, which made it possible to include the February 2022 HICP flash estimate and more up-to-date technical assumptions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For 2024, the ECB staff projections are within a much narrower range of other forecasts for both growth and inflation.

© European Central Bank, 2022

Postal address 60640 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Website www.ecb.europa.eu

All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

For specific terminology please refer to the ECB glossary (available in English only).

PDF ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-22-001-EN-N

HTML ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-22-001-EN-Q

- The cut-off date for technical assumptions, such as those for oil prices and exchange rates, was 28 February 2022. The macroeconomic projections for the euro area were finalised on 2 March 2022. The current projection exercise covers the period 2022-24. Projections over such a long horizon are subject to very high uncertainty, and this should be borne in mind when interpreting them. See the article entitled “An assessment of Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections” in the May 2013 issue of the ECB’s Monthly Bulletin. See http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/index.en.html for an accessible version of the data underlying selected tables and charts. A full database of past ECB and Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections is available at https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browseSelection.do?node=5275746.

- See also Box 2 entitled “Household saving ratio dynamics and implications for the euro area economic outlook”, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2021.

- In order to capture the initial impacts of the war in Ukraine, the window during which futures prices are averaged has been reduced from ten to three working days in order to cover only the period since the start of the invasion.

- The assumption for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields is based on the weighted average of countries’ ten-year benchmark bond yields, weighted by annual GDP figures and extended by the forward path derived from the ECB’s euro area all-bonds ten-year par yield, with the initial discrepancy between the two series kept constant over the projection horizon. The spreads between country-specific government bond yields and the corresponding euro area average are assumed to be constant over the projection horizon.

- Using the Oxford Global Economic Model for global effects on the international environment and the ECB’s New Multi-Country Model (Dieppe, A., González Pandiella, A., Hall, S., Willman, A., “The ECB's New Multi-Country Model for the euro area: NMCM – with boundedly rational learning expectations”, Working Paper Series, No 1316, ECB, 2011) for impacts on the euro area. The ECB-BASE model (Angelini, E., Bokan, N., Christoffel, K., Ciccarelli, M., Zimic, S., “Introducing ECB-BASE: The blueprint of the new ECB semi-structural model for the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2315, ECB, 2019) is also used to assess the impact of second-round effects.

- Both alternative scenarios use the same assumptions for monetary and fiscal policy in the euro area as assumed in the baseline.

- See Gunnella, V., Jarvis, V., Morris, R. and Tóth, M., “Natural gas dependence and risks to euro area activity”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2022.

-

10 March 2022