- SPEECH

Asymmetric risks, asymmetric reaction: monetary policy in the pandemic

Speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the meeting of the ECB Money Market Contact Group

Frankfurt am Main, 22 September 2020

It is a pleasure to speak to the Money Market Contact Group today.

Money markets and central banks have an important relationship which, when it is working well, makes monetary policy more effective. Money market prices reflect expectations of our policy and the understanding of our reaction function. They are the first stage in the transmission of our policies to financing conditions for the real economy.

So I am pleased to talk to you today about how I see current issues related to monetary policy – and to hear your views in return.

The ECB’s policy response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis

In pursuing our price stability mandate, our policy response to the crisis had three goals. The first was to counter the downward impact of the pandemic on the projected path of inflation. The second was to ensure that all parts of the euro area had access to liquidity, which was crucial for weathering the lockdown. And finally, we sought to avoid damaging feedback loops between financial markets and the real economy, ensuring that other policies could play their full role in addressing the effects of the pandemic, in turn making our own policy more effective.

As a result of our policy measures, tail risks have been removed and systemic stress in the euro area has receded (Chart 1). We have averted a liquidity and credit crunch, which would have amplified the collapse in activity and caused lasting damage to production capacity. Without the ECB’s action, the economic consequences of the pandemic would have been dramatic; we estimate that more than one million additional jobs would have been lost.

Chart 1

Euro area composite indicator of systemic stress

After abruptly tightening in March, financial conditions for the euro area as a whole have since eased, as measured for example by the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve. Fragmentation has receded substantially, as the decrease in the dispersion of sovereign bond yields shows. This has safeguarded the transmission of monetary policy, with money market rates reconnecting to the ECB policy rates and sovereign yields reconnecting to risk-free rates, as proxied by overnight index swap (OIS) rates. Euro area real rates have now returned close to their pre-pandemic levels (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Euro area ten-year real rate

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The real rate is constructed by subtracting the ten-year inflation-linked swap rate (ILS) from the nominal ten-year OIS rate. The vertical event lines refer to 19 February 2020 and 18 March 2020.

Latest observation: 18 September 2020.

To give an idea of how our measures have helped, we estimate that the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) and the additional envelope under the asset purchase programme have reduced the term premium in the average ten-year euro area sovereign yield by between 45 and 80 basis points.

The impact on lending conditions has been significant. Our monetary policy measures, complemented by appropriate countercyclical supervisory measures, are enabling banks to keep credit flowing to households and businesses. We estimate that the funding cost relief and capital relief associated with these measures – the combination of which amplifies their individual effects – will increase loans to non-financial corporations by more than 5 percentage points over the period 2020-22; in particular, we expect our targeted longer-term refinancing operations to add 3 percentage points to loan dynamics cumulatively by 2022[1].

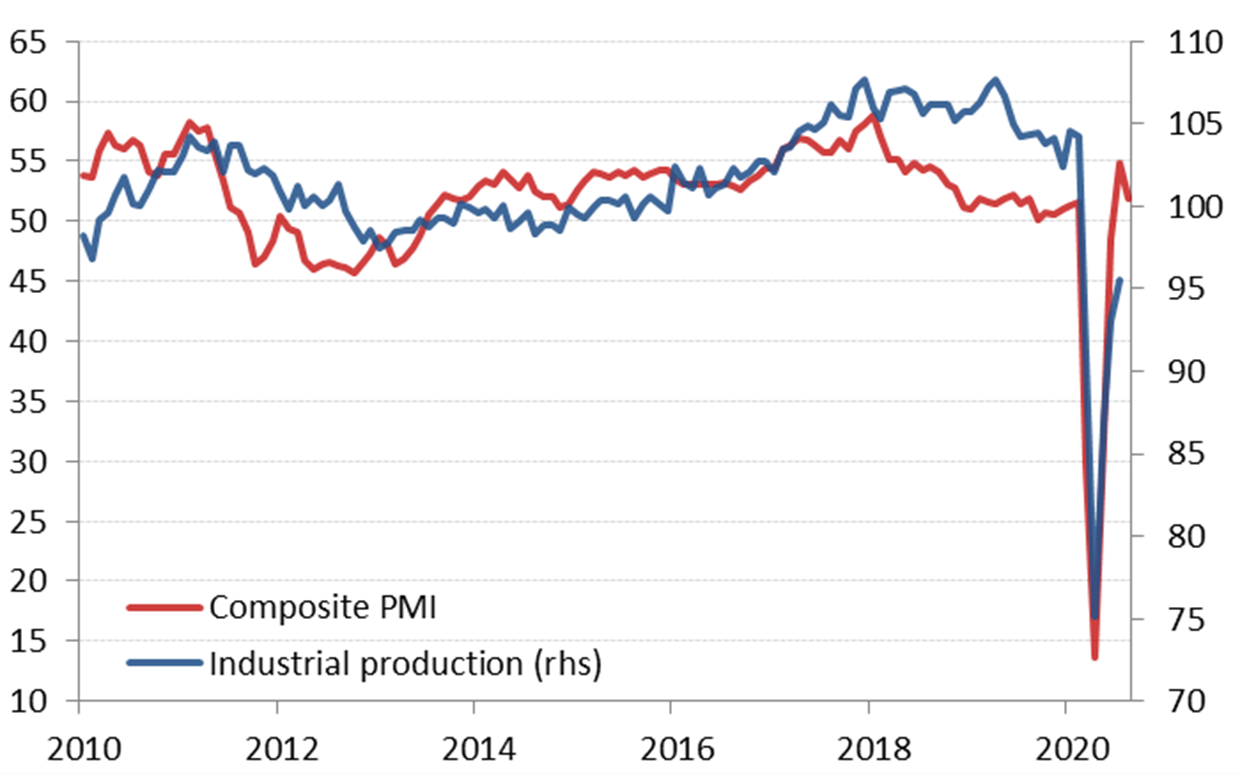

In July, the annual growth rate of loans to firms stood at 7%, more than double its level in February. Bank lending rates, meanwhile, have remained close to historical lows. Benefiting from these developments, industrial production and the Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) have rapidly improved, partly recuperating the previous losses (Chart 3).

Chart 3

Euro area Industrial production and manufacturing PMI

(index)

Source: Eurostat.

Latest observation: July 2020 for industrial production and August 2020 for the PMI.

In this crisis, our independent monetary policy and fiscal policies in the euro area have also mutually reinforced each other, thereby increasing confidence.

By restoring the proper functioning of financial markets, we have removed a major obstacle to expansionary fiscal policies: the euro area aggregate budget deficit is expected to widen to 8.8% of GDP in 2020, while the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve lies in negative territory up to the ten-year maturity. This is the opposite of what we saw during the sovereign debt crisis, when yields increased alongside deficits.

Fiscal support to the economy also made our own policy more powerful. This is obvious in the case of loan guarantees, which ensure that banks do not ration credit to their borrowers in spite of increased uncertainty and credit risk. But active fiscal policy also complements monetary policy through other channels. For example, survey data show that households with more confidence in fiscal support display lower precautionary behaviour. Job protection schemes are a case in point. So, insofar as monetary policy empowers fiscal policy and increases confidence, it also empowers its own effectiveness.

The current economic situation

Today, our monetary policy can gradually focus less on preventing financial and productive collapse and more on securing the return of inflation to our aim. This was the explicit goal of our decision to expand and extend the PEPP in June. And our pandemic support measures are contributing to that goal. The measures we have introduced since March will materially support the inflation and growth outlook: according to conservative estimates by ECB staff, they are projected to increase inflation by around 0.8 percentage points cumulatively between 2020 and 2022, and GDP growth by around 1.3 percentage points.

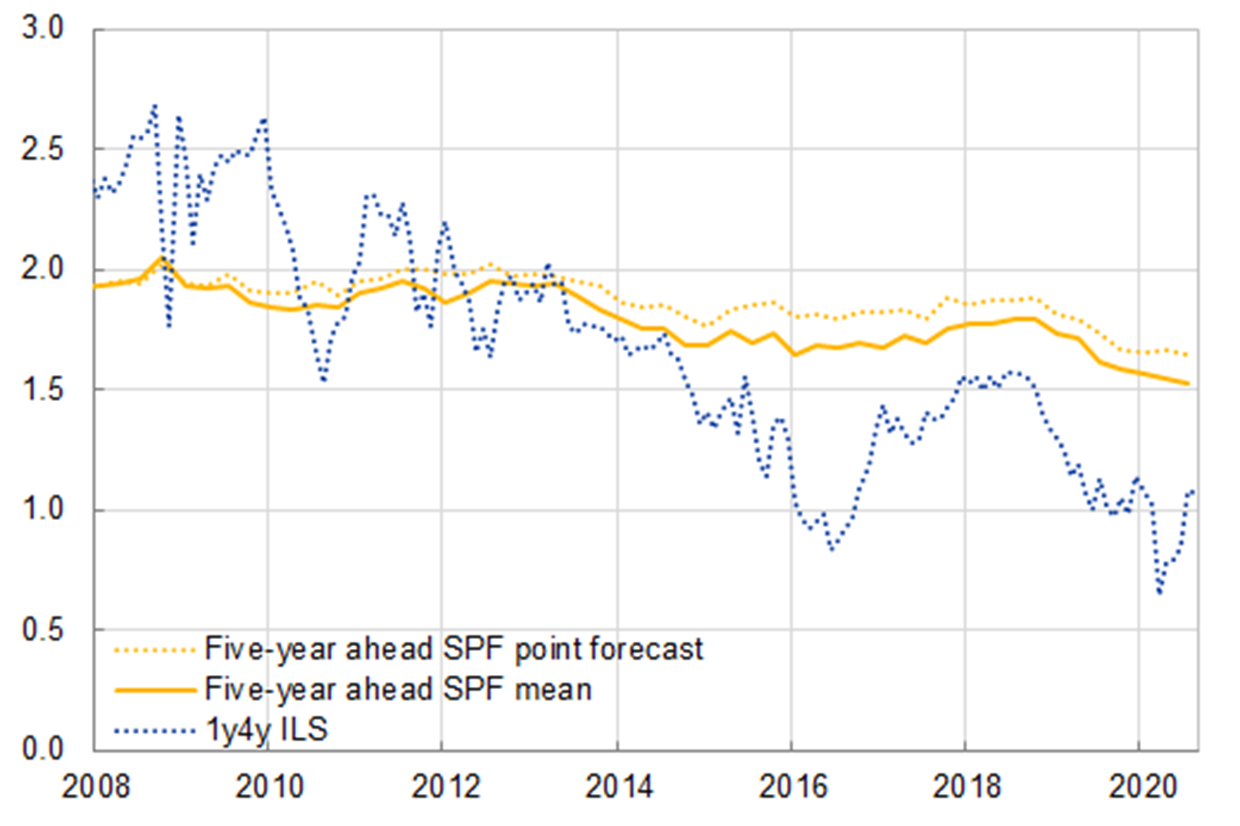

These are remarkable results, but the outlook we face is nonetheless not satisfactory yet. According to the latest ECB staff projections, inflation is expected to remain subdued and to rise to just 1.3% in 2022, still uncomfortably below our aim. Inflation excluding the volatile components of food and energy, which plays an important role in our assessment, rises to only 1.1% in 2022. Longer-term market-based inflation expectations remain very subdued and survey-based measures are at historic lows (Chart 4); real interest rates are higher than would be desirable. Turning to economic activity, the recovery remains partial and uneven; GDP is only expected to recover to pre-crisis levels by the end of 2022.

Chart 4

Inflation expectations in the euro area

SPF inflation expectations and 1y-in-4y ILS rate

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Bloomberg, Refinitiv, and ECB calculations.

Latest observation: The third quarter of 2020 for the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) and August 2020 for the ILS.

This outlook is clouded by an unprecedented degree of uncertainty, not least because it depends on uncertain public health developments. The path to recovery is also exposed to new adverse shocks – such as a possible disorderly Brexit – as well as a loss of momentum due to various emerging economic and financial headwinds.

The appreciation of the euro is one factor that we need to watch closely with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook, particularly at a time when current and expected inflation rates are both very low. The sustained appreciation in the external value of the euro has brought about an undesirable tightening of financial conditions and has offset some of the monetary accommodation provided by our measures.

The services sector, in which momentum has recently slowed somewhat, is another source of concern. PMIs for the services sector worsened in August, likely reflecting its high sensitivity to the rise in COVID-19 infections and renewed social distancing measures. Expenditure on several consumer services remains exceptionally low, and might be affected further by the deterioration of the public health situation in a number of euro area countries. Overall, private consumption in the second quarter of this year was 16.3% below its level at the end of 2019; consumer confidence remains well below its long-term average.

Concerns also emerge from the labour market. Close to five million people lost their jobs in the first half of this year, reversing half of the employment gains since 2013. Looking ahead, job and wage uncertainty is likely to remain elevated and give rise to continued precautionary behaviour among households.[2]

Moreover, credit risk perceived by banks may adversely affect loan supply. Together with corporate balance sheet vulnerabilities, weak aggregate demand and ample spare capacity, this is likely to compress investment. Against this background, new wage negotiations may lead to weaker outcomes, further entrenching weak inflation dynamics.

For as long as the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise across Europe and new restrictions are introduced, it is hard to envisage a strong rebound in consumer sentiment and consumption. And for as long as demand remains uncertain, it is hard to see how business confidence can strengthen and investment can fully recover. This is not a normal recession, and we will not see a normal recovery without appropriate policies.

Future policy calibration

In these difficult circumstances, our policy must remain forward-looking, and there are two key elements to this. First, we need to constantly reassess whether the policy support we are providing and the calibration of our instruments are adequate to address the evolving shocks I have described and to achieve our objective of bringing inflation back to our medium-term aim in a sustained manner. If we encounter shocks that compress demand and pose additional threats to price stability, our reaction function is clearly spelled out: a policy response is necessary and forthcoming.

The second element of a forward-looking policy response relates to how we assess and react to the balance of risks. In this respect, the Governing Council’s view is that the risks to growth are currently on the downside. This expression worries me more today – given the sheer size of the downside risks we face – than it would in less extreme times.[3] Moreover, given the disinflationary nature of the COVID-19 shock,[4] the low inflation expectations and the current levels of spare capacity, I consider a surge of inflation in the medium term above our aim just a remote possibility. As an example, even in a very benign scenario such as the “mild” scenario in the latest ECB staff projections – which assumes a rapid evaporation of the pandemic – inflation would reach 1.8% in 2022.

Faced with such a sizeable downward skew, there is a strong case for our reaction function to be asymmetric, as the risks of a policy overreaction are much smaller than the risks of policy being too slow or too shy to react and the worst-case scenarios materialising.

Against this background, macroeconomic policies – above all monetary and fiscal policies – must remain complementary and the support they provide may be needed for a long time.

The credit market provides a clear example. Our bank lending survey suggests that banks would tighten credit standards considerably if public loan guarantee schemes are not maintained. Since there is evidence that these schemes have significantly suppressed the rate of corporate insolvencies, ending them prematurely at a time when even viable companies may face insurmountable financial barriers could lead to a sharp rise in corporate defaults and the associated adverse effects on banks.

Similar problems would result, mutatis mutandis, from a premature tightening of financial conditions. For as long as the growth and inflation outlook are at risk, monetary policy support will have to remain substantial, and if those risks to the outlook rise, our policy impulse will have to rise in tandem.

EU borrowing in response to the common shock will also be key to avoiding any fiscal cliff effects, through its support to both furlough schemes (SURE[5]) and the recovery (Next Generation EU).

Structural policies also have a fundamental role to play. Given that the job-rich sectors of the economy are the hardest hit by this crisis (Chart 5), the restructuring of our economies is vital: both to generate higher overall growth rates and to produce more and better jobs in other sectors.

Chart 5

Employment growth and contraction due to COVID-19

(percentage points (x-axis), percentage change (y-axis))

Source: Eurostat.

Note: Point size denotes the size of the sector (number of persons employed in a given sector in the fourth quarter of 2019).

This is particularly important for countries with weaker economies and high debt-to-GDP ratios. For these countries, the sizeable funding provided at the European level presents a unique opportunity to address concerns of competitiveness and long-term sustainability. Growth will be the only solution to the accumulation of public and private debt.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. Our monetary policy response to the pandemic has removed adverse tail risks, preserved very accommodative financial conditions in all parts of the euro area and leveraged complementarity with other policies. But the macroeconomic situation remains fragile and uncertain and the projected inflation path is still clearly short of our aim.

Our policy must therefore remain forward-looking in terms of how we evaluate and recalibrate the amount of policy support needed, and how we assess and react to the balance of risks. All macroeconomic policies need to consider the horizon of their measures.

I am now looking forward to hearing your views.

Thank you.

- Altavilla, C., Barbiero, F., Boucinha, M. and Burlon, L. (2020), “The great lockdown: pandemic response policies and bank lending conditions”, Working Paper Series, No 2465, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September.

- See Dossche, M. and Zlatanos, S. (2020), “COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: precautionary or forced?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB.

- The “severe” scenario in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections offers an example of the magnitude of the downside risks to growth that we face. In such a scenario, GDP growth in 2021-22 would be 4.3 percentage points lower than in the baseline scenario in cumulative terms.

- Panetta, F. (2020), “The price of uncertainty and uncertainty about prices: monetary policy in the post-COVID-19 economy”, keynote speech at a capital markets webinar organised by the European Investment Bank and the European Stability Mechanism, 1 July.

- European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE).

Banco Central Europeo

Dirección General de Comunicación

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemania

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Se permite la reproducción, siempre que se cite la fuente.

Contactos de prensa