Private sector involvement: From (good) theory to (bad) practice

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Reinventing Bretton Woods CommitteeBerlin, 6 June 2011

The title of this first session of the conference is: “Policy responses within countries and inside the eurozone since 2010: an appraisal”. The topic is very broad and I cannot cover it in such a short time span unless I am selective and focus on some specific issues.

I would like to consider mainly what has not gone as expected and the disappointments. This enables me to avoid talking, once again, about the ECB’s actions over the last 18 months.

There are at least three things that have gone wrong. The first is that governments of the countries under stress waited too long before recognising that they needed financial assistance, and submitting their requests for support to the IMF and EU. This is true in all three cases, Greece, Ireland and Portugal. More often than not support programmes are delayed and within well integrated economic and financial regions such as the euro area these delays exacerbate market turmoil and create contagion. There is thus an externality in leaving it entirely to the country in question to turn to the IMF and EU for financial assistance. However, experience has shown that when a country requests such assistance, the national authorities tend to blame European institutions, including the ECB, for having pushed them to do so. “Europe” thus becomes a scapegoat and this may fuel strong – although unjustified – anti-European sentiment in the countries concerned. So governments have a natural inclination not to request financial assistance at an early stage.

The second thing that has gone wrong has been the implementation of the Greek programme of reforms. Reform fatigue set in at an early stage and it probably went unnoticed for a while. Member States adopting IMF/EU programmes have to remain firmly committed to very specific measures, which need to be acted upon from the outset. Monitoring has to be strengthened.

I will not elaborate on these two first issues but – being here in Berlin today – I would like to focus on the third issue which has not gone well, in my opinion, namely the whole discussion about private sector involvement. The point I would like to make is that having the private sector actively involved in preventing and resolving sovereign crises is a good idea. However, the practical implementation of this idea is fraught with complications and, if done unwisely, may actually be very damaging, and turn out to be more costly for taxpayers. The events of recent months seem to confirm my views.

I would define private sector involvement (PSI), for the purpose of this discussion, as intentional efforts and contributions, formal or informal, undertaken in a context of sovereign financial distress. This support ranges from softer forms, such as preventive talks, to harder forms, such as debt rescheduling, restructurings, reprofiling or even debt write-downs. [1] [2] In the remainder of my talk, I will look mainly at the harder forms of PSI, often called debt restructurings.

The basic rationale behind involving private creditors when a debtor is in distress is straightforward and uncontroversial: creditors and investors should bear the consequences of their decisions as fully as possible and should not rely on taxpayers’ money to be bailed out. [3] The underlying reason has long existed: a bailout by taxpayers today may encourage risky lending by private investors in the future.

In the corporate sector, it is actually commonplace to apply such principles. Under bankruptcy laws or out-of-court settlement guidelines, such as the London Rules, the Jakarta Initiatives or the Hong Kong Guidelines, when a corporate is facing financing difficulties, the responsibility is passed to the debtor and creditors to arrange debt settlements among themselves. Indebted companies can reorganise and restructure their operations to return to profitability. In turn, creditors agree to reschedule loans or accept the conversion of debt into equity.

While the basic principles of private creditor participation in resolving the debtor’s dilemma are uncontroversial, the application of these principles to sovereign debt is much more complex. Debt workouts in the corporate and public sectors are quite different. First, assessing the solvency of a country is different from that of a company. The former requires not only an analysis of the cash flow, the balance sheet and the assets and liabilities but also an evaluation of the political will to implement the measures needed to ensure that the country remains solvent. The capacity to service debt requires both a willingness and an ability to implement policies that will generate the necessary resources. To quote the example of Greece: it has a gross debt of around €330 billion and marketable assets worth up to €300 billion, so the country is solvent to the extent that it is willing to sell off some of these assets. The same conclusion would be reached by looking at the measures required to achieve a balanced budget, which largely consist of reversing the decisions taken over the last ten years in respect of public sector wage rises, expenditure increases and the adoption of standard structural reforms which would bring Greece in line with other euro area countries. Just to give an example, if, over the last 10 years, Greek public sector wages had gone up at the same pace as inflation, and public employment had not increased, in 2010 the Greek budget deficit to GDP ratio would have been around 4 percentage points lower and the debt to GDP ratio about 30% lower. [4]

The key question is whether the Greek government and the Greek people are willing to implement these measures. The answer to this question largely depends on the alternative scenario, which is a default or restructuring of the public debt. A rational analysis comparing the economic, financial, social and political costs of implementing the needed adjustments, including privatisation, and the costs of a default/restructuring would conclude that the former costs are lower. A rational decision-maker would thus opt for the adjustment and, on that basis, Greece should be considered solvent and should be asked to service its debts.

The second difference between debt workouts in the corporate and public sectors is that, unlike a company, a sovereign cannot be liquidated. There are no insolvency laws or bankruptcy forum to address sovereign solvency problems, and IMF attempts to do so during the last decade failed, for several reasons. What is clear is that in the case of an insolvent sovereign, further official finance can only be provided when that sovereign restructures its debts and, at the same time, undertakes serious and credible domestic fiscal adjustment and structural economic reforms. [5]

The third feature that generally sets sovereign and corporate debt workouts apart is the externalities they may generate. A debt restructuring of a sovereign may have severe implications, both for the debtor’s and the creditor’s economies.

Most of the experience in this area has involved less developed countries. In these cases private sector involvement has largely been a concern for foreign creditors. Taxpayers in creditor countries were affected, depending on the size of the exposure of their respective financial system and on whether the soundness of that system was jeopardised. Measures have been used in the past to try to reduce this impact, in particular through regulatory forbearance. One example is the prudential measures which, during the 1980s, permitted US banks to book Brady bonds at their nominal value.

Historical experience has also rejected the Panglossian view that there exists such a thing as an orderly debt restructuring. While some restructurings have indeed been successful and can arguably be said to have occurred in an orderly fashion, they were often on a small scale and executed under specific circumstances. The most striking and oft-quoted case is Uruguay. However, more often than not, restructurings have been disorderly, harmful and fraught with difficulties. The average length of the negotiations is 2½ years [6] and it can vary greatly. In some cases, negotiations have taken just a few months (for instance, Uruguay in 2003, Pakistan in 1999, Chile in 1990 and Romania in 1983); in other cases they have taken many years (for instance, Vietnam from 1982 until 1998, Jordan from 1989 to 1993, Peru from 1983 to 1997 and Argentina more recently). Empirical evidence also shows that private investors are likely to penalise a country which has a history of restructuring and to demand higher risk premia. [7]

When considering a euro area economy, the following points should be kept in mind. First, the domestic financial market would be severely affected by a default/restructuring of the public debt. Large losses would have to be accounted for, as no forbearance would be possible, and recapitalisation of the domestic banking system would require additional public money. Second, given the role of the state as implicit guarantor of many financial and economic transactions, the impact on the real wealth of the domestic population and on the economy would be substantial. Third, if the government is still running a primary deficit, it will not have the funds to pay for some of its key functions. Fourth, in the euro area the sovereign does not have a domestic central bank that will finance its deficit. Fifth, after a default/restructuring the banking system of the country would be unlikely to pass the stress test and have sufficient adequate collateral to access the ECB’s refinancing operations.

What are the implications of this analysis? Imposing haircuts on private investors can seriously disrupt the financial and real economy of both the debtor and creditor countries. It ultimately damages the taxpayers of both the creditor and debtor country. This is particularly the case in a region like the euro area, consisting of advanced economies with highly integrated financial markets – an integration we have encouraged for years. This is why such restructuring should only be the last resort, i.e. when it is clear that the debtor country cannot repay its debts.

Incidentally, this is the way the international community has functioned and cooperated since the Bretton Woods agreement, which set up the IMF. Countries are never encouraged to default or restructure their debts unless they are in a desperate situation and have no alternative. This is why there have been relatively few cases of debt restructuring and defaults, and they have affected poor and often undemocratic countries.

Where is the problem? The problem emerges when debt restructuring is carried out not as the last resort but as a preventive tool, even becoming a precondition for receiving (or providing) financial assistance, a point mentioned in some official circles since mid-October 2010. Debt restructuring would be a way to tackle not only dramatic cases of insolvency but also any difficulties countries face in accessing the financial markets.

Why is it a problem?

First, as I already mentioned, it would not be a way to prevent taxpayers from suffering the consequences of bad investment decisions. In our Monetary Union, given the integration of financial markets and the single monetary policy, the taxpayers of the creditor countries would suffer in any case. According to the Financial Times, for instance, a default on Greece’s debt would cost the German taxpayers alone “at least €40 billion”. [8]

Second, this would be a way to punish patient investors, who are sticking to their investment and have not sold their bonds yet, and are confident that with the adjustment programme the country will get back on its feet. Restructuring would instead reward the investors who exited the market earlier or short-sold the sovereign bond, speculating that they would gain out of a restructuring.

Third, it would destabilise the euro area financial markets by creating incentives for short-term speculative behaviour. Given that markets are forward-looking, they would try to anticipate any difficulty faced by a sovereign by short-selling their positions, thus triggering the crisis. This would discourage investment in the euro area because of its potential volatility and perverse market dynamics.

Finally, such a measure would delay any return to the market by a sovereign, because no market participant would be willing to start reinvesting in the country for a long period if they know that this kind of investment might at some stage be penalised. This would thus discourage private sector involvement and oblige the official sector to increase its financial contribution.

A clear example is the fear that private sector involvement would be sought automatically under the European Stability Mechanism. Faced with such circumstances, investors would be sceptical about buying government bonds maturing after 2013. And the statement which is often made in this country that “there will be no restructuring before 2013” does little to reassure investors, as it implies that there might be one afterwards.

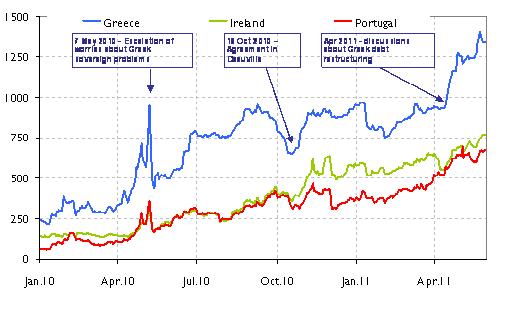

The proof of what I have just mentioned can be found in the data. Just looking at the yield spreads between the government bonds of the three stressed countries and those of Germany, it can be seen that they were gradually coming down last autumn until the day of the Deauville agreement and then spiked up after the October European Council, in which it was mentioned that preparatory work on the ESM would include “the role of the private sector”. Renewed public comments about a possible “soft restructuring” or “reprofiling” of the Greek debt in April this year produced an immediate spike of the spreads on Greek bonds, with strong contagion effects to other euro area countries (see Chart 1).

To sum up, private sector involvement, if pursued imprudently, i.e. automatically rather than as the last resort:

does not help save taxpayers’ money; indeed, it may cost them more money;

favours short-term speculation over long-term investment, which is certainly undesirable;

discourages and even delays any new investments in a country implementing an adjustment programme.

Given that such a system – of preventive PSI – does not exist elsewhere in any other parts of the world, the euro area would be seen by investors as handicapping itself and it would feel the effects of discrimination. The euro area, in terms of both sovereign and private investments, would become less attractive. The financial system in particular would be highly exposed to sovereign restructuring.

It would also put the euro area at odds with the rest of the international community. Given the damage that such a system would inflict on other investors and countries, the other shareholders may be discouraged from supporting IMF programmes in the euro area.

This is how a good idea can turn into bad practice. Continuing to pursue it suggests strong masochistic tendencies.

How should the problem be solved? How can we prevent taxpayers of the good performers in the euro area from being asked to foot the bill for the excesses of the bad performers?

EMU is based on two pillars. The first is price stability, ensured by an independent central bank. The second is sound public finances, promoted by the Stability and Growth Pact. This second pillar has not worked properly and needs to be repaired.

Including some form of automatic private sector involvement does not repair the SGP. It actually weakens it by delegating discipline to the financial markets, which we know are late and pro-cyclical. It makes debt restructuring easier and thus discourages fiscal discipline.

The only way to protect taxpayers in “virtuous” countries is to avoid over-indebted countries from easily getting away with not repaying their debts; the payment of debts should be enforced, through sanctions if need be. When countries go off track they can receive financial assistance only in exchange for strict adjustment programmes, including asset sales, which allow these countries to remain solvent. Respect for contracts is the one of the key principles underlying the market economy. It is also the basis of monetary union between sovereign countries.

-

[1]See Enderlein, Müller, and Trebesch, 2006.

-

[2]Soft forms of private sector involvement include those that would not change the terms and conditions of the bonds or loans. Such forms may include voluntary roll-over agreements and preventive talks and meetings. By contrast, harder forms of private sector involvements imply changes to the terms and conditions of the bonds or loans. Under some forms, the private sector participants may face a net present value loss, in other cases they would not face such a loss.

-

[3]See US Treasury Secretary Rubin, 1998.

-

[4]The results of the simulations have to be viewed with caution since they are sensitive to the quality of the underlying data and the assumptions used in the exercise.

-

[5]See, for instance, Roubini, 2002.

-

[6]See Trebesch, 2008.

-

[7]See, for instance, Reinhart et al. 2003 and Ozler, 1993.

-

[8]See FT, 24 April 2011.

Banco Central Europeu

Direção-Geral de Comunicação

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A reprodução é permitida, desde que a fonte esteja identificada.

Contactos de imprensa