From Convoy to Parting Ways? Post Crisis Divergence Between European and US Macroeconomic Policies

Comments on the paper by Jean Pisani-Ferry and Adam Posen,

by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB,

at the “The Transatlantic Relationships in an Era of Growing Economic Multipolarity”, Conference hosted by the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Bruegel,

Washington, DC, 8 October 2010

The paper is extremely interesting and stimulating. I will not discuss all the arguments, but will rather focus on a few issues, mainly related to monetary policy, given my comparative advantage. In the paper, Pisani-Ferry and Posen try to explain the differences in policies on both sides of the Atlantic on the basis of underlying economic fundamentals and policy preferences. I would like to make three main observations.

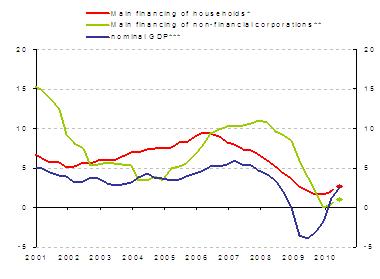

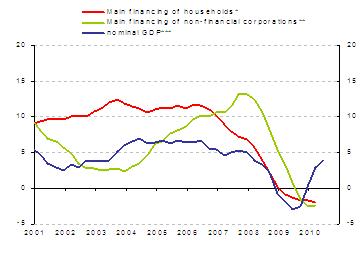

The first observation relates to the role that underlying economic conditions play in explaining policy differences. I would like to add one element that has not been fully explored in the analysis. It refers to the transmission of monetary policy in a post-bubble economy. In particular, the flow of credit to the private sector in the euro area seems to differ from that in the United States. Considering the overall amount of lending to households and non financial corporations, supplied both by the banking sector and by the capital market, there has been a recovery in the euro area in recent quarters (Chart 1). In the United States, credit to households and to the corporate sector, by contrast, has been in negative territory for some time (Chart 2). This might be explained by both demand and supply factors. As Pisani-Ferry and Posen have shown, before the crisis US households and corporates had a higher debt levels than their euro area counterparts and have had to progressively deleverage. On the supply side, US banks are probably also deleveraging more quickly.

This difference in the flow of financing to the private sector partly explains the different techniques followed in the implementation of monetary policy on the two sides of the Atlantic. It may also explain the differences in the results achieved. To be sure, the ability to consistently anchor inflation expectations throughout the crisis has enabled the ECB to effectively reduce real interest rates in the euro area, as shown in Chart 3, and thus to support economic activity.

The second point is about the lessons that central banks can learn from the past to guide their future monetary policy. Pisani-Ferry and Posen cite three episodes in the past which central bankers should look at carefully, namely the Great Depression, Japan’s lost decade and, more generally, previous experiences of post-financial crisis periods. We all certainly take a great deal of interest in, and inspiration from, these episodes. Looking at other post-crisis experiences, like that in Japan, some lessons can be learned. Let me mention three:

After a financial and housing bubble has burst (what about the primary commodities bubble?), the growth potential is impaired, and possibly even reduced, for some time. According to all major international institutions, this also applies to the current period.

Monetary policy can smoothen the transition to the new steady state, but it cannot by itself pull the economy back to the pre-crisis level, which was not in a sustainable equilibrium, within a short period of time.

The recapitalisation and restructuring of the banking system is far more important than monetary policy in avoiding a credit crunch.

There are, of course, other lessons to be learned from past episodes. But in my view, we should also look at another important period of history, the period that preceded the crisis. In my view, there is much more to learn from the decade that preceded the crisis than from other experiences. To be sure, this crisis has confronted the economics profession with the challenge of rethinking its analytical basis. Central banks cannot be immune from such an exercise. We should not be afraid of taking a critical look at the recent past. Let me mention seven lessons from the recent past that may be useful for the future.

The growth recorded in advanced economies that experienced large current account deficits over the last decade was not sustainable. For macroeconomic policies to continue to be aimed at the attainment of similar rates of growth in the future would imply generating the same imbalances that led to the crisis.

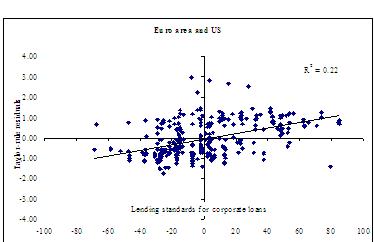

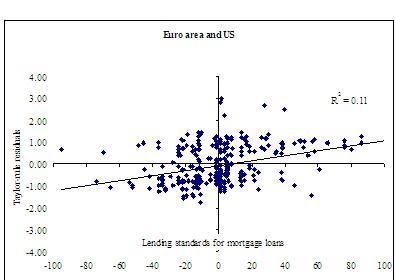

Very low levels of interest rates for a prolonged period of time can result in a misallocation of resources and encourage risk-taking that fuel asset price bubbles. There is now increasing evidence of this correlation (see Charts 4 and 5). I consider it not to be fair for central bankers to shift all the blame for the build-up of the bubble before the crisis to only regulators and market participants.

The view that monetary policy should not look at financial market conditions and should only intervene to counter the effects of the bursting of the bubble (i.e. what has been labelled the “Greenspan put”) has proved to be wrong.

Interest rates were kept too low for too long before the crisis, mainly on account of fears that the economy would enter a Japanese-style deflation, fears that turned out to have been mistaken. Risk management-type monetary policy aimed at avoiding deflation is thus not without risk.

Monetary policy cannot by itself transform a jobless recovery into a job-generating recovery. If anything, keeping the cost of capital excessively low may encourage capital-intensive investment, rather than labour-intensive capital expenditure.

Core inflation is not a good predictor of headline inflation, nor of underlying inflationary pressures emerging in a global economy.

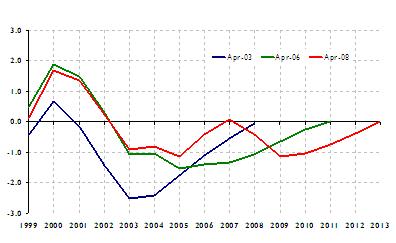

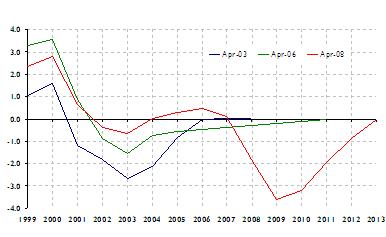

It is very difficult to measure output gaps. This is not a new finding, but it tends often to be forgotten. Looking at the period before the crisis, what looked like as a large output gap in 2003 turned out to be a very small one a few years later. Therefore, it is very dangerous to calibrate monetary policy mainly on the basis of this variable (see Charts 6 and 7).

If we want to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, we have to keep these lessons in mind.

This leads me to the third point I would like to make. It relates to the position of central banks in the institutional framework underpinning economic policy-making in our societies. Pisani-Ferry and Posen argue that in countries where the relationship between the central bank and the government is “unproblematic”, the central bank is freer to go beyond its usual mission, in particular with respect to the adoption of non-conventional measures.

In fact, the institutional framework underlying the ECB does not prevent it from taking non-conventional monetary policy measures of the type that other central banks have done. The ECB did not embark on large-scale purchases of government bonds of Member States because it could not do so, but because we did not consider that to be an appropriate instrument in conducting monetary policy. The non-conventional measures we adopted relied more on the banking system, given its prominence in the transmission of monetary policy in the euro area. I have shown previously that our measures have been as effective, if not more effective, than others in providing liquidity to the financial system. Selected purchases of government bonds were used only in exceptional circumstances, to address specific problems in the transmission of monetary impulses.

It is clear that embarking on large-scale purchases of government bonds may affect the relationship between the central bank and the fiscal authority. What I am not sure of is when such a relationship can be characterised as “problematic” or “unproblematic”. Reading the paper, I gained the impression (perhaps wrongly) that a “problematic” relationship is one in which monetary and fiscal policies are distinct, as is the case in the euro area. I would then like to ask: “Just where is the problem if monetary policy is kept distinct from fiscal policy, and cannot be manipulated by the fiscal authorities to solve budgetary problems?” Perhaps it is a problem for the fiscal authorities, because they would like to use the instrument of monetary policy to inflate away the fiscal problems and have, instead, to resort to fiscal measures that are subject to parliamentary approval and that all citizens are able to judge and assess.

It seems to me that it is not a problem for the citizens at large, especially for the less wealthy, that fiscal problems are not solved through the inflation tax or by keeping the rate of interest on public debt instruments artificially low. To be sure, for the European population at large, the role of the central bank should remain distinct from that of the fiscal authorities, and monetary policy should remain firmly in the hands of the central bank. This is why the prohibition of monetary financing of the government and the independence of the central bank have been enshrined in the Treaty. It is the best way to ensure that budgetary problems are addressed in a democratic way, rather than through the manipulation of the currency, which has hidden distribution effects on the population. In Greece, Ireland and Spain, in France and Germany, the governments are adopting budgetary policies in full awareness of the fact that they cannot count on the inflation tax to solve their fiscal challenges, challenges that all advanced societies have to face. Can we consider this to be a problem?

Let me conclude on a broader issue, related to the title of the conference: Transatlantic Relationship in an Era of Growing Economic Multipolarity. At many of the conferences on trans-Atlantic relations that I have attended in the past, participants often discussed the decreasing relevance of these relations in the light of the new emerging global powers. Interestingly, when we get to discuss monetary issues, trans-Atlantic relations remain important. The reason is that they are the only relevant ones.

A great deal of attention seems to be devoted to potential – and I would add, minor – differences and divergences between policies in Europe and the United States, while the rest of the world is completely forgotten. The paradox of major emerging market economies asking for a greater say in global governance, but at the same time shying away from responsibility in monetary matters has thus far captured little attention. Many important emerging market economies either do not have any monetary policy at all, because they have pegged their exchange rate to the currency of an advanced economy, or impose capital controls and restrict the international use of their own currency. This creates monetary divergences that are much larger in scale than those we discussed today, with global repercussions. Thus, rather than talking about “monetary wars”, which makes little sense, more attention should be devoted to what I would call a “monetary void” in the world economy. As a result of such a void, many of the problems experienced by advanced economies before the crisis, like very low levels of interest rates – especially in comparison with the underlying rate of economic growth – are now migrating to emerging markets, with potentially very critical consequences for both these economies and the global system. More attention needs thus to be paid to these issues, and to their consequences with respect to achieving a balanced and sustained recovery of the global economy.

Thank you for your attention.

Chart 1: Nominal GDP, Debt financing – EA

annual percentage changes, nsa

Source: EAA, ECB and Eurostat.

Note: * includes loans, ** includes loans, debt securities and liabilities for direct pension commitments of employers (i.e. not including other payables). The latest observation 2010 Q2 is estimate from BSI data. *** Nominal GDP calculated as simple annual growth rates. Latest observation: 2010 Q2.

Chart 2: Nominal GDP, Debt financing – US

annual percentage changes, nsa

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, BIS.

Note: * includes credit market instruments (i.e. loans not including other payables) and debt securities issues by non-profit organisations, ** includes loans, debt securities and liabilities for direct pension commitments of employers (i.e. not including other payables). Latest observation: 2010 Q1. *** Nominal GDP calculated as simple annual growth rates. Latest observation: 2010 Q2.

Chart 3: 5-year real yield 5 years ahead in the EA and the US (%p.a.)

Source: Reuters, Bloomberg, FED staff calculations, ECB calculations. Latest observation: 5 Oct 2010.

Note: 5-year 5 years ahead constant maturity zero-coupon yield based on triple A inflation-linked bonds for euro area. 5-year 5 years ahead constant maturity zero coupon yield based on TIPS for the United States.

Chart 4: Monetary policy and financial stability (i)

Corporate loans

Source: Maddaloni and Peydró-Alcalde (2010).

Chart 5: Monetary policy and financial stability (ii)

Mortgage loans

Source: Maddaloni and Peydró-Alcalde (2010).

Chart 6: Spring vintages of EA output gap estimates by IMF

Source: IMF (WEO)

Note: Output gaps are defined as the percentage deviation of actual output from potential output

Chart 7: Spring vintages of US output gap estimates by IMF

Source: IMF (WEO)

Note: Output gaps are defined as the percentage deviation of actual output from potential output

Banco Central Europeu

Direção-Geral de Comunicação

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A reprodução é permitida, desde que a fonte esteja identificada.

Contactos de imprensa