Financial turmoil, securitisation and liquidity

Speech by José Manuel González-Páramo, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBGlobal ABS Conference 2008Cannes, 1 June 2008

1. Introduction [1]

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to be here in Cannes. I would like to thank the European Securitisation Forum for giving me the opportunity to share with you some views on the current financial market turmoil, with a particular focus on the developments in the structured finance market, both from the perspective of market conditions and of monetary policy implementation.

The fact that the markets for asset-backed securities (ABSs) have played a key role in the current market turmoil shows the increasing importance of credit securitisation for global financial markets. Securitisation, together with financial innovation and technological progress in the financial industry, has indeed changed the way many banks operate. The securitisation of their loan portfolios has provided banks with access to an additional funding source and enabled them to mitigate some of the risks intrinsically related to their core business of liquidity transformation.

However, the market turmoil has also revealed vulnerabilities in the markets for asset-backed securities and the related “originate to distribute” model that need to be addressed in order to minimise the risk that, instead of contributing to social welfare, securitisation may in practice create risks for economic and financial stability.

2. The economics of securitisation: Benefits and some drawbacks

The role of securitisation in the financial markets of developed economies has expanded dramatically in recent years. Following a relatively slow start compared with the US market, the European market for asset-backed securities grew very rapidly in the past few years as entrepreneurs, bankers and investors increasingly warmed up to the advantages of instruments that allowed them to issue bonds backed by the cash flows from pools of asset classes as diverse as music royalties from rock stars, rental income from pubs, and soccer club ticket sales, as well as more boring stuff such as credit card debt and mortgage loans. [2] Also some European governments were quick to spot the attractiveness from new financial instruments that enabled them to raise funds from the securitisation of future government revenues - whether from the expected sales of real estate holdings and lottery tickets or from pension contribution claims - rather than from more traditional mechanisms of financing public spending that are usually not very popular with voters.

There is no sector though more closely involved in securitisation than the banking sector. In fact, asset securitisation was introduced in the 1970s in the US precisely for the purpose to allow depository institutions to sell their pools of mortgage loans before maturity, thereby acquiring an additional source of funding. Banks subsequently extended the securitisation model to other forms of credit, such as consumer credit and student loans, that were historically regarded as highly illiquid.

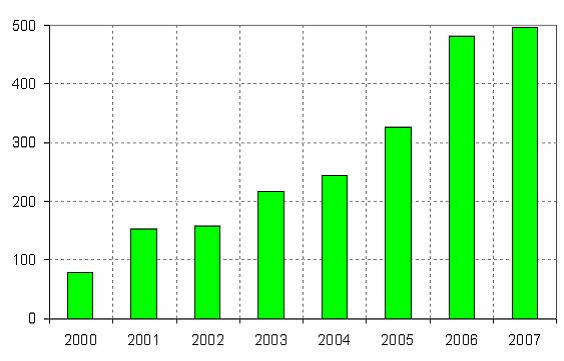

In Europe, the market for structured finance products has grown rapidly during the last 5-10 years, often at double-digit rates (See Chart 1). This development was maybe even more pronounced in the euro area compared with other regions due to several factors, including the introduction of the single currency, further financial market integration through the use of credit derivatives and related financial instruments, and an innovative financial industry. [3] Growth in structured finance products has also been fuelled by high demand from investors stemming from the search for yield and diversification opportunities. Securitisation has also been positively affected by the move towards a more market-based financial system.

Increasing securitisation of lending-related assets, together with relentless financial innovation in credit markets, have led to the diffusion of a new business organisation – the “originate to distribute” model – among banks, particularly those of large size. There is certainly no need to explain to this audience how, under this new business model, the loans originated by banks are transformed into marketable asset-backed securities.

However, it may be worth recalling that this is not the way banks have historically done business. Under the traditional – perhaps, I should say secular – “originate to hold” business model, banks extend loans to firms and households and hold them in their balance sheets until they mature or are paid off. Banks finance the provision of loans mainly by collecting deposits or issuing debt that have typically shorter maturities. Thus, banks intrinsically face a maturity mismatch in their balance sheets that exposes them to funding liquidity risks, i.e. possible difficulties in funding their business activities. [4]

By allowing banks to transform their illiquid assets into marketable securities and providing an additional source of funding to expand lending, securitisation provides an effective mechanism to mitigate such risks and reduces the role in liquidity transformation traditionally performed by depository banks, with potential implications also for the monetary policy transmission mechanism. [5]

An additional attraction is that, by securitising their loans, banks have often in the past economised on costly capital requirements. In fact, it has been argued that, under the Basel I accord, regulatory capital arbitrage has been one of the main reasons why banks have adopted the “originate to distribute” model. Finally, it should be noted that securitisation can also be a source of fees and income for banks with expertise in the structuring of asset-backed securities.

Also from the point of view of the economy as a whole, the “originate to distribute” model can potentially yield a number of benefits. First, being capital costly, the ability to sustain a given level of credit supply with a lower volume of capital enables the banking sector to reduce the costs of financing for borrowers and favours financial development, which is ultimately associated with economic growth. Moreover, securitisation may be seen as representing a step towards more complete credit markets, thereby contributing to enhancing the efficiency of the economic system.

In addition, the securitisation of loans in principle could reduce a secular source of vulnerability of the economies, by taking risk concentrations associated with loan portfolios away from the balance sheets of the banking sector and spreading them more broadly across other sectors. As a result, the “originate to distribute” model may potentially diminish the likelihood of the credit busts and banking crises that have historically been a major source of macroeconomic and financial instability in many countries.

It should be noted though that, even before the outbreak of financial market turmoil, some commentators have voiced doubts about some of the welfare-enhancing effects of the “originate to distribute” model. For instance it has been argued that, while securitisation certainly spreads existing risks, it may in fact encourage the creation of further risks, particularly by relaxing the incentives for banks to screen and monitor borrowers in order to alleviate the informational asymmetries associated with credit contracts. [6] Incidentally, it should be recalled that, when assets-backed securities were in their infancy, concerns about the risks for investors stemming from the possible relaxation of lending and monitoring standards by banks were among the main reasons for scepticism about the prospects of the market for securitised loans.

In addition, it has been questioned whether the securitisation of loans has succeeded in ensuring risk diversification. Indeed, for many banks all over the world, risks do not seem to have travelled farther away than the balance sheets of their own conduits, and have been internalised again once the market turmoil erupted. Besides, some banks turned out to have direct exposures through their own investment activity on structured products and secondary exposures via some of their customers.

While this certainly does not mean that securitisation is not potentially welfare-enhancing, it suggests that – in the environment of historically low returns on traditional securities and an implied imprudent hunt for yield that preceded the turmoil – the markets for asset-backed securities and credit derivatives may have failed to spread risks as effectively as expected and have, by contrast, exacerbated information asymmetries, probably as a result of their opacity and the complexity of the underlying contracts.

Overall, the “originate to distribute” banking business model has taken a hit and its survival has been questioned. There is clearly a need to reflect carefully on the model and its increased reliance on secured and off-balance sheet funding. For example, several types of banks involved to varying degrees in the “originate to distribute” business model turned out to be vulnerable to the rapid re-pricing on the ABS products, in particular banks with small deposit bases and strong reliance on wholesale funding.

Also, as mentioned earlier, the model may have negatively affected origination standards, by weakening lenders’ incentives to monitor the quality of the loans they wrote, as the distance between borrower and the ultimate bond holder increased. The increasing complexity of the instruments made it even harder to understand the composition and quality of underlying assets.

However, despite of these deficiencies, it is clearly not the end of this business model. As alluded to before, securitisation is a long-established and broadly used financing technique that covers a vast range of asset classes. There is still demand for related financial products from certain types of investors. Since the fundamental business idea behind the model is still valid, hopefully a more sustainable version of it will evolve.

3. Vulnerabilities of securitisation during the turmoil

After an extended period of ample liquidity and generally low credit spreads in many economies and markets, sharp losses in the value of US subprime mortgages and an associated evaporation of investor appetite triggered broad distress in structured finance markets during the summer of 2007. Losses were magnified by illiquid markets for many types of structured instruments, leading to sharp decreases in secondary market prices.

When the first downgrades of ABS backed by pools of sub-prime mortgages in the US took place, the ABS market – which is not very deep even in normal times - dried-up nearly entirely. Even though the problem arose in the sub-prime market, spreads on ABSs backed by corporate bonds, bank loans, credit cards and auto loans increased substantially as well, clearly indicating a contagion effect. Thus, from end-July the market turbulence depressed securitisation activity in general. As a result, after having reached record highs during the months preceding the summer, the issuance of ABSs declined sharply.

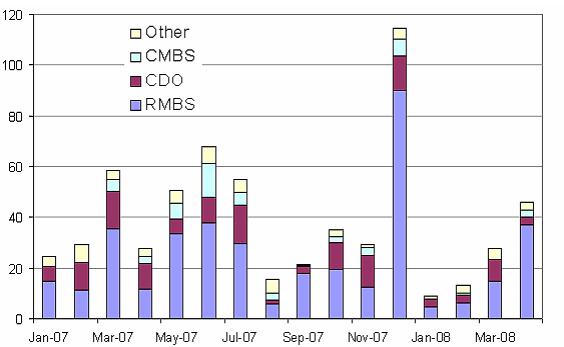

Some asset classes in the structured finance markets have been hit more severely than others (Chart 2). This concerns the most complex instruments such as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) squared, synthetic CDOs and constant proportion debt obligations (CPDOs). Among the more traditional products, commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBSs) saw a significant decline in issuance activity.

Indeed, in the latter part of 2007, due to lowered demand for structured credit products coupled with an uncertain outlook for commercial property markets, issuance of CMBSs came to a halt. Issuance activity in the euro area during the last quarter of 2007 dropped to €2 billion from €6.2 billion one year earlier. Also, European CMBS issuance activity during the first four months of 2008 was approximately 28% of the level corresponding to the same period of the previous year.

In comparison, residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBSs) have dropped only by 15% during the same time period between 2008 and 2007 and the issuance level in March-April this year was actually higher compared with the same period last year.

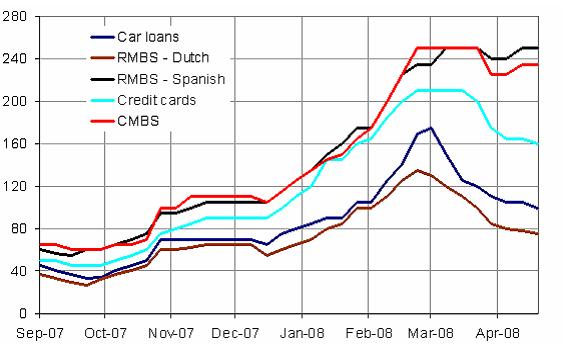

The sharp re-pricing of credit and liquidity risk in ABS secondary markets had an impact also on supply and demand conditions in primary markets. Prices, measured as spreads over Euribor rates, started to increase during the summer 2007 and some of the spreads stand now above 200 basis points above the 3-month Euribor rate (see Chart 3). Also, potential investors such as private banks, investment funds and hedge funds have become reluctant to invest at these levels and adopted a wait and see attitude, in the hope of even better spreads or clearer signs about future directions. As a consequence of this increase in risk aversion, the primary market is facing a mismatch between supply and demand: issuers do not want to sell at current conditions, and investors do not want to buy until prices have bottomed out.

4. The Eurosystem’s collateral framework and the ABS market during the turmoil

Let me dwell a bit on the role of our operational and collateral framework during the turmoil. Since its inception the operational framework of the Eurosystem has been tested on several occasions. The present market turmoil has posed new challenges, and in many aspects even more significant than those faced in the past. Overall, the Eurosystem’s operational framework, including its collateral-related component, has served us well during the market turmoil and has proven robust under stressed conditions.

One contributing feature to its resilience is the fact that a broad range of counterparties, including all types of credit institutions irrespective of their size and the scope of their business, may access the credit operations of the Eurosystem, including the temporary refinancing operations. Moreover, credit is granted against a wide range of collateral. This implies that sufficiency of collateral should not become a constraint for counterparties. These two features of the operational framework in combination with the large scale temporary refinancing operations have certainly helped the Eurosystem to effectively mitigate funding liquidity risk for counterparties when interbank markets stopped functioning properly.

In order to understand better the specific role which ABSs fulfil in the implementation of our monetary policy, let me just remind you of some key elements of our collateral framework. The Eurosystem has a broad definition of debt instruments and against this background a wide range of public and private securities, including asset-backed securities, can potentially become eligible if they fulfil all the other eligibility criteria. Indeed, compared with the traditional concept of other central banks in the world, the Eurosystem accepts a large volume of high quality ABSs, and has done this well before the outbreak of the financial market turmoil. In addition to the general eligibility criteria, such as the denomination in euro and compliance with our minimum rating threshold, some specific requirements apply to ABSs: (i) only the most senior tranche of an ABS structure is eligible; (ii) ABSs must be backed by assets that have been legally acquired by the special purpose vehicle (SPV) in a manner that the Eurosystem considers to be “true sale”, and (iii) the issuing SPV must be located in the European Economic Area (EEA). There are no special restrictions on the underlying assets backing the transaction, with one exception, namely that underlying asset pools may not consist of credit derivatives. Hence, a broad class of ABSs may qualify as collateral, both residential- and commercial-backed securities, all sorts of consumer credit backed ABSs, cash-flow collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) and CDOs. Overall the volume of eligible ABSs constitutes approximately 60% of the entire outstanding European securitisation market.

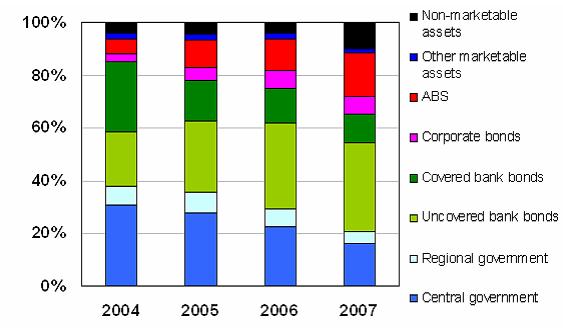

As regards the developments in the use of collateral since the start of the turmoil (see Chart 4), they show clearly that counterparties have made active use of the leeway the collateral framework provides. Quite understandably, they have economised on the use of central government bonds, which has been often almost the only collateral counterparties could still use in interbank repo markets. Instead they have brought forward less liquid collateral to the Eurosystem, including ABSs, for which primary and secondary markets have basically dried up. The annual average share of asset-backed securities pledged as collateral increased to 16 percent in 2007, up from 12 percent in 2006 and 6 percent in 2004.

However, I would like to issue a note of caution here. The fact that counterparties post ABSs as collateral with the Eurosystem does by no means imply that those assets are refinanced on a one-to-one basis by us. The majority of national central banks operate with a so called “pooling system”, in which much more collateral can be deposited with the central bank than counterparties actually need to cover their outstanding credit with the Eurosystem. In fact, during the turmoil precautionary buffers have increased very significantly, and there is on an aggregate level a large amount of over-collateralisation in collateral pools held with the Eurosystem. Hence, only a part of the ABSs deposited as collateral with us are effectively refinanced in our temporary operations. Nevertheless it is fair to say that the ability to use ABSs as collateral with the Eurosystem helps counterparties to hedge the refinancing risk of those assets.

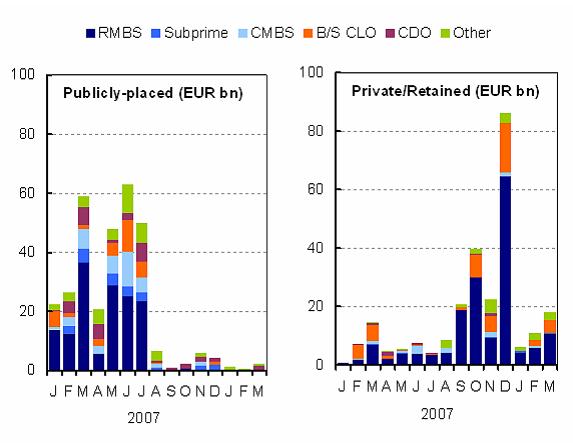

One phenomenon which shows to what extent the primary and secondary markets for ABSs have become dislocated since the outbreak of the turmoil is the fact that many ABS transactions were not placed in the public market but taken onto the balance sheet of the originator and/or privately placed. Indeed, as shown in Chart 5, issuance of publicly placed securitised products in Europe declined substantially in August last year and has since September hovered around a very low level per month. At the same time, deals that have been privately placed or retained by the originator have been consistently higher than public issuance since August, reaching a peak of around €90 billion in December 2007.

The Eurosystem’s collateral rules may partly explain why at least euro denominated securitisation issuance has not come to a halt notwithstanding the withdrawal of third party investors. As indicated before, we accept only those ABSs for which the transfer of underlying assets has been achieved via a true sale and where the issuing entity is bankruptcy remote from the originator of the transaction. These requirements should in principle ensure the de-linkage of the issuer from the originator. Nevertheless, these requirements do not rule out that counterparties may use ABSs as collateral with us which they have originated themselves and retained on their balance sheet. The possibility for banks to use as collateral ABSs that they have originated themselves may have prevented a complete shut down of primary markets. However, in the medium term this cannot be an alternative to the restoration of a deep and orderly functioning market which offers true secured funding possibilities. I strongly believe that the industry needs to make serious efforts to revive the interest of third party investors.

One very telling development in this context is that, as a consequence of the retained issuance, the quality of the documentation underlying issuances, such as pre-sale reports by rating agencies and prospectuses, seems to have deteriorated. Hence, contrary to expectations that issuers would enhance transparency to restore investor confidence, we witness signs or indications of the opposite development towards ever more opaque markets. I will come back to this issue of transparency later again.

5. Taking stock

Let me take stock at this stage. Overall the operational framework of the Eurosystem has served us well during the ongoing financial market turmoil. In particular, thanks to the built in flexibility of its collateral framework, the Eurosystem has been able to step in effectively when intermediation in interbank markets deteriorated, without the need to make changes to its framework. As a side effect of the broad range of assets accepted as collateral, the framework helped us also during the turmoil to address liquidity squeezes in some markets, including the ABS market, as it mitigated refinancing risks for asset classes that had become illiquid. This has contributed to financial stability in the euro area. Other central banks may have had those effects in mind when they initiated changes to their operational framework in the wake of the turmoil, leading to a significant degree of convergence among the various frameworks.

Of course, the ability of the Eurosystem’s operational framework to respond to the challenges for monetary policy implementation posed by the recent period of financial market volatility does not mean that there is no scope for further improvements and refinements. For instance, the eligibility criteria for marketable debt instruments have been kept general in order to ensure that the collateral framework of the Eurosystem is responsive to financial innovation. There is therefore a concomitant need for the Eurosystem to refine its collateral policy, including the risk control measures, and ensure that the collateral continues to meet the Eurosystem’s risk tolerance level and allows the effective implementation of monetary policy. This has already been done in the past from time to time, with a view to further enhance the collateral framework.

Let me give you just two examples. First, different liquidity categories were introduced in February 2004 to better mirror the risks associated with different asset classes. More liquid central government debt instruments are in category 1, while less liquid asset-backed securities are in category 4 to reflect the limited secondary market liquidity of those instruments. The second example is the establishment of the previously mentioned specific eligibility criteria regarding asset-backed securities, which were inter alia introduced in 2006 to exclude instruments such as synthetic CDOs and cash CDOs containing other synthetic tranches of ABSs. Due to the opaqueness of the market and the product complexity, those instruments were not deemed suitable as collateral for central bank credit operations. The current developments confirm the appropriateness of the measure.

The currently ongoing market turmoil has presented us with a wealth of information both on how our collateral framework interacts with financial markets and financial market participants and on the appropriateness of our risk control framework. We will continue to assess carefully the collateral we receive and make sure that the rules outlined in the collateral framework are strictly applied, as well as to study whether there are elements in our collateral framework that may need to be refined to make it even more effective.

6. Going forward: Transparency

The recent events have highlighted a number of weaknesses in the financial system, namely in the areas of transparency, valuation, risk management practices, the current prudential framework and market functioning. These weaknesses as well as related policy recommendations from a wide range of fora and organisations have attracted considerable attention over the past months. In my final remarks today, I would like to focus on an area with major repercussions for the smooth functioning of markets, namely: transparency

There is common agreement on the view that a sound transparency framework based on improved disclosure, high-quality accounting standards and solid valuation practices is pivotal for ensuring market confidence and enhancing market discipline. In this respect, the financial market turmoil brought to the forefront a number of shortcomings: disclosure of information on risk exposures to and valuations of structured products and off-balance sheet vehicles proved to be opaque and very diverse in terms of scope and detail, complicating comparison across financial institutions. Furthermore, at the instrument level, the information provided to the market by institutions involved in the securitisation process has been limited, especially in relation to the quality of underlying asset pools. This lack of transparency both on exposures to instruments and at the level of the instrument itself contributed to the loss of market confidence and, as I mentioned earlier, led to disruption in various segments of the financial markets. The complexity and opacity in instruments supported also to an over-reliance on ratings and rating agencies.

There are various policy initiatives under way to address the aforementioned shortcomings: At the EU, in accordance with the Ecofin roadmap, CEBS (in coordination with the industry) has been mandated to review public disclosure of types and amounts of securitisation exposures, significant individual transactions and Special Purpose Vehicles exposures by banks and to consider complementary guidelines. [7]

At the international level, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), following the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) recommendations, will issue further guidance to strengthen disclosure requirements under Pillar 3 of the Basel II framework. [8]

However, the onus of identifying areas of improvement and providing useful disclosures that allow investors to assess the risk/return profile of financial institutions rests primarily with the industry. In this respect, I would like to make special reference to the European Securitisation Forum that since the early stages of the turmoil has acknowledged the importance of enhancing transparency. As you know, its work addresses the pertinent issues of (i) developing guidelines of best practices concerning securitisation disclosures; (ii) providing periodic aggregate data concerning the securitisation market and (iii) enhancing information to investors on the composition and performance of underlying assets at issuance and on an on-going basis. Availability of information is critical to maintain incentives along the securitisation chain and to enable market participants to make informed decisions. The quality of the documentation underlying issuances, such as pre-sale reports by rating agencies and prospectuses, should be improved. In addition, a sufficiently detailed disclosure of borrower characteristics and the performance of the loans over time would be important to revitalise the market. This is also of critical importance to the central banks in the Eurosystem, not only as market watchers but also, as I mentioned earlier, in the performance of their task of providing regular refinancing to the banking system against adequate collateral. Here I would like to echo the recommendations on transparency in securitisation markets made by the Financial Stability Forum [9] to have standardised information about the pools of assets underlying structured credit products.

Supervisors and central bankers are encouraging and monitoring the market-led initiatives by the European Securitisation Forum and other international organisations and will evaluate the adequacy of these measures as well as their implementation to assess whether they need to do more. Having said that, I would like to underscore again that the interventions of public authorities cannot substitute the need for the market to enhance disclosure by providing information that will facilitate the assessment of the situation of financial institutions and financial instruments. This will eventually lead to reinstatement of confidence in the ability of the financial system to manage risks properly.

I thank you for your attention and I wish you all very interesting days here in Cannes.

Chart 1. European securitisation issuance (EUR billion)

Source: European Securitisation Forum

Chart 2. Funded issuance by collateral (EUR billion; by month)

Source: JP Morgan

Chart 3. European ABS spreads (relative to 3-month Euribor)

Source: JP Morgan

Chart 4. Evolution of collateral held with the Eurosystem by asset type

Source: ECB

Chart 5. European securitised products: Publicly placed or privately retained? (EUR billion)

Source: Citi. European Secutitised Products. Strategy Analysis. Securitised Products. Europe 7 March 2008. Secondary Source: Bloomberg, International Insider, Informa GM, IFR, Citi. Note: Publicly-placed issuance includes only deals that have been publicly marketed. Private/Retained issuance includes deals that have been privately-placed or retained by the originator. The Private/Retained issuance figures include all such deals to Citi’s knowledge, but may not include such deals where there is no public information available. For some deals priced since August 2007 it has not been clear whether the deal has been fully placed.

-

[1] I am very grateful to Pontus Aberg, Valia Rentzou and Isabel Von Koppen-Mertes for their valuable inputs and contributions, and to David Marqués for useful comments.

-

[2] See ECB (2008), “Securitisation in the euro area”, Monthly Bulletin, February.

-

[3] See ECB (2007), Structural Issues Report on “Corporate finance in the euro area”, May.

-

[4] Funding liquidity refers to the ability of a bank to: (1) convert its assets into cash by disposing of them or borrowing against their value in order to meet expected and unexpected obligations, or (2) to issue liabilities in order to raise funds.

-

[5] According to some tentative empirical evidence, increasing securitisation may diminish the impact of monetary policy impulses on banks’ loans supply via the so-called “bank lending channel”, although the effect of securitisation seems to depend on the economic cycle and bank risk (see Altunbas, Y., Gambacorta, L. and D. Marqués Ibáñez (2007), “Securitisation and the bank lending channel”, ECB Working Paper 838.

-

[6] See Rajan, R. (2005), “Has financial development made the world riskier?”, NBER WP 11728 and Sufi A. and A. Mian (2008) “ The Consequences of Mortgage Credit Expansion: Evidence from the 2007 Mortgage Default Crisis”, paper presented at the May 2008 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Banking Structure Conference

-

[7] Scheduled to be completed by June 2008.

-

[8] Scheduled to be completed in 2009.

-

[9] See “Report of the Financial Stability Forum on Enhancing Market and Institutional Resilience”, FSF, April 2008.

Banco Central Europeu

Direção-Geral de Comunicação

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A reprodução é permitida, desde que a fonte esteja identificada.

Contactos de imprensa